Squirrel bottle, Salem, North Carolina, 1804–1829. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 8 1/4". (Private collection; unless otherwise noted, photos by Gavin Ashworth.)

Squirrel bottle and mold, Salem, North Carolina, 1820–1850. Lead-glazed earthenware (bottle) and plaster (mold). H. of bottle 6 1/4". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Left: Owl mold, Salem, North Carolina, 1804–1830. Plaster. H. 5 1/2". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.) Note the narrow opening at the top of the mold through which slip was poured to create the reproduction example. Right: Slip-cast owl figure next to a fragment of a base recovered at the site of the Schaffner-Krause pottery. Unfired slip-cast earthenware and bisque-fired earthenware. H. 6 1/4". (Courtesy, Michelle Erickson [owl figure] and Old Salem Museums & Gardens [fragment].)

Spout mold, Salem, North Carolina, 1820–1850. Plaster. (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

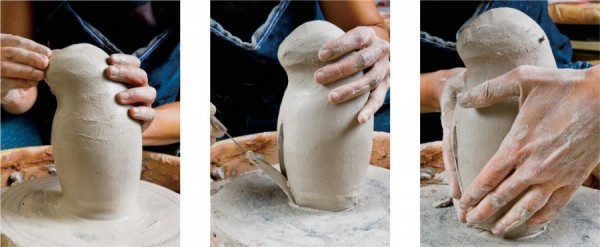

To produce an original model for the squirrel bottle, first a thick cylinder is raised on the wheel. The thickness allows for enough clay to create the sculptural aspects of the squirrel’s body and provides strength for the model during the mold-making process. The top portion of the cylinder is closed and roughly shaped to approximate the body of a squirrel. The trapped air provides the resistance needed in this type of modeling.

The cylinder is sculpted by hand to outline the figure. A sliver of clay is removed to transform the circular form into an oval.

The body features continue to be modeled creating the proportions and character of the original. The roughed-out form is removed from the wheel for the final detailing.

Detail of the back of a molded plate, recovered at the site of Rudolph Christ’s pottery, Bethabara, North Carolina, 1786–1789. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 9 3/4". (Courtesy, Historic Bethabara Park.)

A decorative feature along the tail of the squirrel bottle illustrated in fig. 1 is a rouletted line of beads within incised circles. For this feature, a roulette was carved in plaster and used to create the pattern in the soft clay.

A series of incised lines is used to define the tail.

The finished model ready to cast. Note the feet, arms, and ears of the squirrel are not part of the master model. Separate models and molds are required for these appendages as per the originals. A clay slab has been prepared to receive the lower half of the body before casting. Note the triangular registration keys that have been prepared. Such keys can be seen in the Moravian molds.

A clay wall is used to seal the interior and act as a retaining wall when the plaster is poured.

After the plaster has been poured and allowed to cure, the mold is removed. The same procedure is conducted for the opposite half of the model, resulting in a two-piece mold.

The paws and base require only one-piece molds. The model for the base is thrown as a saucer-shaped form and manipulated to create a rough oval. The details of the feet are modeled into the base and cast. The arms/paws are modeled individually. All of the components are fitted to the model of the body to ensure placement and fit.

Paw fragment, recovered at the site of the Schaffner-Krause pottery, Salem, North Carolina, post-1834, with a paw mold. Bisque-fired earthenware (paw); plaster (mold). (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens [paw], Wachovia Historical Society [mold]; photo, Wesley Stewart.)

This image shows the components of the modeling and molding process. At the top is the original squirrel-body clay model in the two-piece mold created from it. At the bottom are the master model of the arms and one-piece press mold taken from it, the feet and base master model and one-piece mold, and, next to the roulette wheel, a press mold used to create the eye detail.

Slabs of clay are prepared and pressed into each half of the plaster mold. Care is taken to press the clay firmly and evenly into the mold to ensure that the details are transferred. It is important to keep the clay in place to avoid overlapping impressions.

A heavy bead of slip made from the same clay body is applied along the edges of the clay halves.

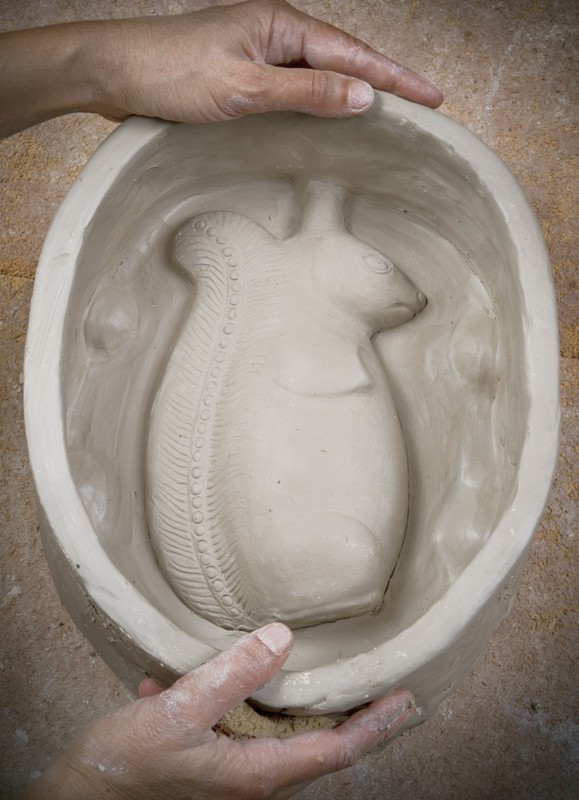

The two halves are pressed together using the keys in the plaster mold to aid proper alignment of the halves.

After the two halves are joined, the figure is allowed to dry in the molds to absorb the moisture in the clay. The molds can now be removed, leaving the newly created body. The seams on the body are smoothed and trimmed as necessary.

The base is removed from the mold in preparation for assembly. Note the very stylized representation of the squirrel’s feet.

The base and arms are attached to the body using slip and the seams are blended in at the point of attachment.

Squirrel bottle, Salem, North Carolina, 1804–1829. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 8 1/4". (Courtesy, The Metropolitan Museum of Art.)

Squirrel bottle, Salem, North Carolina, 1804–1829. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 8 1/4". (Private collection.)

Squirrel bottle, Salem, North Carolina, 1804–1829. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 8 1/4". (Private collection.)

Detail of the squirrel’s tail on the bottle illustrated in fig. 25.

The ears are applied and sculpted by hand, followed by the final finishing of the molded bottle.

The finished molded squirrel bottle. In this final stage, the bottle is slowly air dried and then bisque fired. The glaze is applied after the first firing. The Moravian glazes include a deep green, a rich dark brown, and a tortoiseshell or Whieldon-type glaze with underglaze oxide colors of green and brown.

Second Amendment Squirrel, Michelle Erickson, Hampton, Virginia, 2009. Unfired earthenware. H. 9 1/4". (Private collection.)

One of the most iconic objects associated with North Carolina’s Moravian potters is the figural squirrel bottle produced in the Salem workshops. More surviving examples of this molded, lead-glazed earthenware form have been recorded than any of the other animal figures from the pottery’s output. Although the actual circumstances surrounding the introduction of these molded bottles in the Moravian pottery are unclear, the squirrel was in production as early as 1803 and apparently was produced in large numbers for several decades afterward.[1]

As early as the 1750s the North Carolina Moravian potters used simple molding technologies to manufacture clay tobacco pipes and stove tiles. Staffordshire potter William Ellis, who visited in 1773, appears to have introduced plate molds and sprigging molds, both made from plaster of paris.[2] How the more complex, multipart molds needed for the production of figures—a staple of contemporary Staffordshire and German production techniques—came into the Moravian pottery is not entirely clear. Ellis might have had such molds, since John Bartlam employed them in South Carolina for his creamwares. A plaster sauceboat mold dating to the 1786–1789 period was recovered archaeologically at Rudolph Christ’s Bethabara pottery, suggesting Christ was acquainted with two-piece mold technology.[3]

The production of the molded bottles has generally been ascribed to Christ’s innovations at the Salem pottery, although it seems more likely that an outside source introduced the sophisticated process of creating models and multiple molds. The most obvious candidate would be German ceramist Carl Eisenberg, who arrived in Salem in 1793 and spent time disseminating his technologically sophisticated methods and formulas for making faience.[4] While we have physical evidence of Eisenberg’s faience, particularly his greenish blue ring bottle, we do not know how long he worked in the pottery or whether he made molded forms. For the moment, the identification of the progenitor and circumstances surrounding the introduction of the molded bottle technology into the Salem pottery remains a mystery.

At least two different models of squirrels were made in Salem, each requiring its own mold. The most typical is a large bottle, averaging about 8 1/2 inches in height, in which the squirrel is in a very upright posture (fig. 1). The second, less common example is smaller, 6 3/4 inches, with the squirrel stooped over in a more alert stance (fig. 2). One half of a plaster mold for the smaller example survives, but a mold for the larger model has yet to be recovered.

The purpose of this article is to examine the production of the squirrel bottle using the more common upright example as the basis for the investigation. Others have addressed mold technology—including taking contemporary casts from existing molds—but somewhat superficially, as many underlying technical considerations have been glossed over.[5]

As Johanna Brown discusses in her article on Moravian press-molded wares in this volume, the squirrel was a popular pet and the subject of whimsical representation in paintings, toys, and various ceramic objects in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. While the inspiration for the various animal figures has been explored, the physical origins of the models used by the Moravian potters remain poorly understood. Were they copies of European prototypes, or were they the artistic creations of someone in the Salem pottery?

At least one bottle form—the turtle—seems to have been cast directly from a natural specimen.[6] The squirrel model takes the form of an Eastern gray squirrel (Sciurus carolinensis) sitting erect on its haunches and supported by an oval base. Its tail is erect against its back, and its forepaws were cast in a variety of poses. While the modeling is clearly stylized, someone with artistic skill captured the essence of the animal, showing it to be pensive and alert, its large eyes in a fixed gaze and its delicate ears cupped to catch any sudden sounds. The maker also understood the process of making molds and casting, ensuring the squirrel body avoided undercuts, which would hinder the subsequent release of the mold when casting. The need to avoid complex surfaces required several different molds to create components that were assembled by the potter after the casts were made.

Using plaster molds for the rapid casting of identical clay forms—whether vessels or figures—has inherent technical challenges. Molds made from soft plaster are subject to warping and premature wear if not used properly, and, where fine detail is critical, some have a working life of only a few dozen casts. The relatively simple body molds used by the Moravians could have been used more than one hundred times before the mold had to be replaced. The progressive wear of the molds can be observed on extant bottles, some of which display very crisp details, whereas others have very worn areas. For a busy pottery, molds would have to be recast from the master models several times a year, which helps explain the variations seen among the Moravian figures; minor changes over the course of many years are part of the process.

Worn plaster molds could not be recycled, so for the best-selling bottles Moravians potters must have been constantly making new molds and discarding the old ones. As no mold for this popular squirrel bottle survives, we can speculate that they must have been used to extinction and the original model must have been lost.

Whether the Moravian figural bottles were press-molded or slip-cast was a subject for discussion at the outset of this project. Visual examination suggests that solid slabs of clay were used for creating the two-piece bodies; however, all of the extant molds have what appears to be a hole for pouring slip into the cavity. Yet the diameter of the hole is relatively small, which would have made pouring the slip in a timely fashion—required for making a successful cast—somewhat difficult.

An experiment with slip casting was conducted using an original small owl mold, and a successful example was produced (fig. 3). However, it was not accomplished easily, as the thick slip did not pour freely through the narrow opening in the mold, which took ten to fifteen minutes to fill. In contrast, modern slip-casting and most period molds have a much larger opening and the casting slip has a finer particle size, which allows molds to be poured in a matter of seconds. The coarser slip solutions available to the Moravians would have made this process even more difficult, if possible at all. Ultimately, it was decided that the hole in the molds probably acted as a vent for releasing trapped air during the press-molding process, which would result in a better adhesion of the two parts of the clay body.

The replication process began with an analysis of the squirrel bottle to identify the components that made up the finished product, and three major ones were found: the squirrel body and tail; the set of front paws; and the oval base, which includes the feet. Other, minor elements included the spout and the ears, which were added after the completion of the molding of the three body components. An existing spout mold (fig. 4) in the Old Salem collection suggests that this might have been molded separately, as a variation of the squirrel form. The ears of the squirrel, which are fairly delicate, were modeled and attached separately at the end of the process. These elements permit some flexibility in the final assembly, giving the potter options that will be illustrated below.

With the assumption that the original model was made from clay, a facsimile was made as a potter might proceed rather than a sculptor working in wood or plaster—that is, the model was made approximately 10 percent larger than the existing antique examples, to account for the shrinkage that occurs during drying and firing.

A cylinder was first raised on the wheel approximating the height, exterior dimensions, and general anatomical shape (fig. 5). Slots cut in the circular form realign the walls of the cylinder to form the oval shape of the squirrel body (fig. 6). Once the general form of the body was established, it was cut from the wheel to do the final hand modeling (fig. 7). The general contours of the animal’s limbs and musculature are shaped, then the mouth, nose, and eyes are added. A small plaster mold was created to press the eye into the clay.

The sculpting of the tail required the most consideration. On the original that served as the prototype for this article, a beaded device runs the entire length of the tail, perhaps simulating the squirrel’s vertebrae. It has raised dots within impressed circles spaced at regular intervals, a pattern that was created with a roulette. Moravian potters were very familiar with roulettes, as evidenced on their fineware or creamware products (fig. 8). A roulette was carved into plaster and used to replicate the beaded pattern for this project (fig. 9). After the roulette was rolled along both sides of the tail, incised lines were added along this spine, to convey the bushiness of the squirrel’s tail (fig. 10).

Once the sculpting of the body was completed, preparation for making a two-piece plaster mold began by constructing a clay casting chamber. The body of the squirrel was placed into a temporary clay slab at the midpoint of the body line (fig. 11) with a clay wall surrounding the slab (fig. 12). Casting plaster was poured into the chamber.

After the plaster body had set up, the clay retaining wall was peeled way and the mold was removed (fig. 13). The mold was then turned upside down and used as the base for casting the reverse side of the squirrel body. Before pouring the next batch of plaster, the first side of the mold was covered with a soapy solution to prevent the plaster halves from sticking together—the pottery equivalent of greasing a baking pan. Care was taken to create registration keys to align the two halves of the plaster mold, features that can be found on all of the surviving Moravian molds.

A similar process was used to create plaster molds for the model of the base and feet and one for the front paws (fig. 14). It was only necessary to created one-piece molds for these components. An original front-paw mold exists in the Wachovia Historical Society collection (fig. 15). Once all of the molds were thoroughly dried, the process of creating a replica squirrel could begin (fig. 16).

The body is the first component to be made. Two slabs of white earthenware clay were rolled out and pressed into each half of the body mold (fig. 17). Care was taken to push the clay into all of the contours and crevices of the mold, to ensure that a reliable impression would result. A generous amount of white slip was trailed along the edges (fig. 18) of each body half, and the two molds were pressed together, taking care that a proper alignment was maintained (fig. 19). The mold was firmly pounded to attach the two body halves.

The cast body is allowed to dry slightly in the plaster molds (fig. 20). Once removed, the seam between the two halves is trimmed and smoothed as necessary, using a fettling knife to conceal the juncture. Using slip, the body is then attached to the cast base/feet, and the seams are smoothed out (fig. 21). The cast paws are attached in a similar fashion (fig. 22). Of course, the purpose of using molded elements is to allow for repetition of identical final products. However, the attachment of the paws permits some flexibility in the final appearance of the squirrel. Extant examples of squirrel bottles show a number of variants in the positioning of the paws. In most examples the paws are empty and held to the mouth in a feeding posture, although one example has a nut placed in the front paws as an added element to the composition (fig. 23). Other variations include the placement of a molded spout at the terminus of the tail (figs. 24, 25), as opposed to the rudimentary opening at the top of the head seen on the prototype example in figure 1. Other variations that can be readily observed are the different decorative treatments of the tail. The detail in figure 26 shows a tail without the rouletted bead detail but in which the vertebrae are represented with a more rudimentary punctuate decoration.

The ears are the last element to be added (fig. 27). The assembled squirrel is now dried and fired to bisque (fig. 28). Prior to a final firing, as per the originals, a brown or green glaze is applied. A tortoiseshell glaze, using copper and manganese oxides, was also popular.

The Moravian molded figural bottles occupy a revered place among collectors of Southern ceramics as well as students of American decorative arts. The survival of many of the plaster molds present an incredible resource for further exploration by ceramic technologists to understand fully the range and variation of the products. We know the squirrel bottles were first made about 1803, possibly earlier, and excavations at the Schaffner-Krause pottery site suggest that the molds were still in use as late as 1834, and possibly later.[7] As new specimens come to light in the antiques marketplace, we hope that a chronology can be established through a careful analysis of the molding details, some of which have been identified in this article.

The inventory of the pottery in Salem of April 30, 1804, lists “23 Owls and Squirrels,” but they must have been in production before 1804 because the 1804 estate sale of Joseph Wells, a Quaker who died in Orange County, North Carolina, in September 1803, includes a “Squirrel bottle” purchased by Joseph Johnson along with a teapot for 7s. 6d. See in this volume Johanna Brown, “Moravian Press-Molded Earthenware,” p. 112.

See in this volume Robert Hunter, “Staffordshire Ceramics in Wachovia,” p. 84.

See Brown, “Moravian Press-Molded Earthenware,” fig. 10.

Bradford L. Rauschenberg, “Carl Eisenberg’s Introduction of Tin-Glazed Ceramics to Salem, North Carolina, and Evidence for Early Tin-Glaze Production Elsewhere in North America,” Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts 31, no. 1 (Summer 2005): 47–52.

John Bivins Jr., The Moravian Potters in North Carolina (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press for Old Salem, Inc., 1972), pp. 207–9.

See Brown, “Moravian Press-Molded Earthenware,” fig. 14. A complete two-piece mold for a turtle bottle is in the collection of Old Salem Museums & Gardens.

See in this volume Michael O. Hartley, “Salem Pottery after 1834: Heinrich Schaffner and Daniel Krause,” fig. 20.