Detail of the squirrel bottles illustrated in figure 2. (Unless otherwise noted, photos by Gavin Ashworth.)

Squirrel bottles, Salem, North Carolina, 1804–1829. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 8 1/4". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens [left], Wachovia Historical Society [right].) Flying squirrels and gray squirrels were popular pets throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. John Singleton Copley’s portrait of his young half brother, Henry Pelham, depicts Henry’s pet squirrel nibbling on a nut in much the same posture as one of the Moravian bottle variants.

Pipe heads, Bethabara, North Carolina, 1756–1772. Lead-glazed earthenware and bisque-fired earthenware. H. 1 1/2". (Courtesy, Historic Bethabara Park.)

Stove tile, Bethabara or Salem, North Carolina, 1760–1800. Bisque-fired earthenware. H. 8 5/8". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens; photo, Wesley Stewart.) This tile matches sherds recovered at one of Aust’s kiln waster dumps at Bethabara.

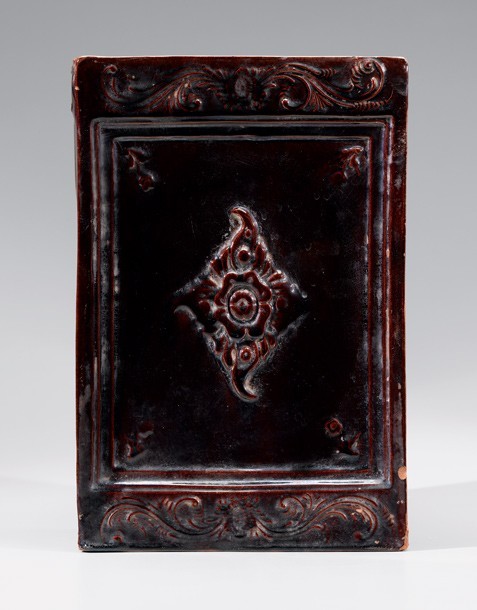

Stove tile, Bethabara or Salem, North Carolina, 1760–1800. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 8 5/8". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Stove tile mold, Bethabara or Salem, North Carolina, 1760–1800. High-fired clay. H. 9 1/4". (Courtesy, Wachovia Historical Society.)

Stove tile, Salem, North Carolina, 1760–1800. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 10 1/2". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Plate mold, Bethabara or Salem, North Carolina, 1786–1795. High-fired clay. D. 8". (Courtesy, Wachovia Historical Society.) This mold, which might have been taken from a clay model or a pewter plate, could be one of the forty molds Christ brought from Bethabara to Salem in 1789.

Detail of the back of the mold illustrated in fig. 8.

Sauceboat mold, Bethabara, North Carolina, 1786–1789. Plaster. (Courtesy, Historic Bethabara Park.)

Barrel, Salem, North Carolina, 1790–1825. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 4 3/4". (Courtesy, Wachovia Historical Society.) In most inventories of the Salem pottery, “small barrels” are listed with the press-molded figural bottles.

Fish bottle and mold, Salem, North Carolina, 1801–1830. Lead-glazed earthenware (bottle); plaster (mold). L. of bottle 9 3/4"; L. of mold 11". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens [bottle]; Wachovia Historical Society [mold].) This mold exhibits much less wear than most of the surviving examples.

Inkwell, John Holland, Salem, North Carolina, 1810–1830. Lead-glazed earthenware. W. 5". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.) This inkwell bears Holland’s incised initials. Its design and fabrication suggest that Holland was a competent potter, despite the fact that

his wares often drew complaints from

customers.

Turtle bottle and mold, Salem, North Carolina, 1800–1850. Lead-glazed earthenware (bottle); plaster (mold). L. of bottle 7 1/4". (Courtesy, Wachovia Historical Society.)

Turtle bottle, Salem, North Carolina, 1800–1820. Lead-glazed earthenware. L. 8 1/2". (Private collection.)

The underside of the turtle bottle illustrated in fig. 15.

Detail of the top of the turtle bottle illustrated in fig. 15.

Squirrel figure, Staffordshire, England, ca. 1790–1800. Pearlware. H. 6 3/4". (Courtesy, Sotheby’s.)

Squirrel bottle, Salem, North Carolina, 1804–1829. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 8 1/2". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Squirrel bottle and mold, Salem, North Carolina, 1820–1850. Lead-glazed earthenware (bottle); plaster (mold). H. of bottle 6 1/4". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Owl bottle, Salem, North Carolina, 1804–1840. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 5 1/2". (Private collection.) The mold for this bottle is in the Wachovia Historical Society Collection at Old Salem Museums & Gardens.

Owl bottle, Salem, North Carolina, 1804–1840. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 7 3/4". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Owl figure, Staffordshire, England, 1790–1810. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 5 3/4". (Courtesy, Chipstone Foundation.)

Owl jug, Staffordshire, England, 1695–1710. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 9 1/8". (Courtesy, Chipstone Foundation.)

Bear bottle, Salem, North Carolina, 1810–1830. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 6 3/4". (Private collection.) The 1810 inventory of the Salem pottery lists forty-four bear bottles at 1s. 6d. each.

Fox bottle or caster, Salem, North Carolina, 1810–1830. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 5 1/2". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.) The base of this bottle has been restored.

Fish bottles, Salem, North Carolina, 1801–1829. Lead-glazed earthenware. L. of largest 9 3/4". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.) Although the 1819 inventory of the Salem Pottery lists fish bottles in four sizes, the 1829 mold inventory lists only three.

Fish bottle, Salem, North Carolina, 1801–1829. Lead-glazed earthenware. L. 8". (Private collection.) Slight variations among extant fish, even those of the same size, attest to the existence of multiple models and molds. The decorator of this example outlined the fish’s eyes.

Fish flask, Tell el-Yahudiya, Egypt, 1650–1550 b.c. Unglazed earthenware. L. 7 5/8". (Courtesy, Collection of University College London.)

Crayfish bottle, Salem, North Carolina, 1801–1840. Lead-glazed earthenware. L. 4 1/4". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Crayfish bottle, Salem, North Carolina, 1801–1840. Lead-glazed earthenware. L. 6 1/2". (Private collection.)

Doll head mold, Salem, North Carolina, 1820–1850. Plaster. H. 2 3/4". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.) The 1824 inventory of the Salem pottery listed 803 dolls in three sizes. They probably were not the same as the “lady bottles,” which were not listed with toys. The large number of doll heads in the inventory suggests that the pottery was making them to sell to other retail outlets.

Bird figure, Salem, North Carolina, 1810–1820. Lead-glazed earthenware. L. 2 3/4". (Courtesy, Wachovia Historical Society.) Bird figures of this type were probably intended as toys. The mold for the body of this example survives. The rather indistinct features of the head suggest that it was modeled by hand rather than produced in a second mold.

Sheep head fragment, Salem, North Carolina, 1834–1860. Bisque-fired earthenware. L. 3/4". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Garden.) This fragment was recovered at the site of Heinrich Schaffner’s pottery. Sheep and birds are listed as toys in the 1824 inventory of the Salem pottery.

Dog figure, England, 1825–1835. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 1 1/2". (Private collection.) Dog figure mold, Salem, North Carolina, 1819–1850. Plaster. H. 2 1/8". (Courtesy, Wachovia Historical Society.) The mold might have been taken from an English dog figure such as the example illustrated here.

Lady bottle, Salem, North Carolina, 1806–1830. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 9 1/4". (Private collection.) Lady bottles appear in four sizes on inventories beginning in 1806.

Lady bottle, Salem, North Carolina, 1806–1830. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 5 1/2". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.) This example probably represents the smallest of the lady bottles. It has a cluster of small holes in the back and a single, larger hole in the bottom, suggesting that this object functioned as a caster. None of the larger lady bottles has small piercings.

Chicken caster, Salem, North Carolina, 1810–1850. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 4". (Private collection.)

Bottle, Salem, North Carolina, 1790–1820. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 6 1/2". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Eagle bottle, Salem, North Carolina, 1819–1830. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 5 1/2". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Eagle bottle mold, Salem, North Carolina, 1819–1830. Plaster. H. 6 1/2". (Courtesy, Wachovia Historical Society.) According to the 1819 Salem pottery inventory, eagle bottles were made in two sizes. This mold was probably for the smaller size. The larger one is oval in shape and slightly taller than the round one illustrated here, although the eagle motif is the same size on both.

Bottle, Salem, North Carolina, 1800–1830. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 6 1/2". (Courtesy, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.) This bottle was found in Randolph County, which is adjacent to Alamance County.

Flask, probably southern Alamance County, North Carolina, 1760–1790. H. 5 3/8". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Tart plate molds, Salem, North Carolina, 1806–1829. Plaster (left); high-fired clay (right). D. of left mold 6". (Courtesy, Wachovia Historical Society.)

Tart plate fragment, Salem, North Carolina, 1806–1829. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.) This fragment was excavated on one of the lots used by the Salem pottery.

Leaf dish and mold, Salem, North Carolina, 1807–1829. Lead-glazed earthenware (leaf dish); plaster (mold). L. of dish 8 1/2"; L. of mold 10 1/4". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation [dish], Wachovia Historical Society [mold]; photo, Hans Lorenz.)

Leaf dish mold, Salem or Bethabara, North Carolina, 1786–1821. L. 9 1/4". (Courtesy, Wachovia Historical Society; photo, Hans Lorenz.) The mold is marked “RC.” No dishes of this pattern have been identified.

Duck tureen or sauceboat, Salem, North Carolina, 1819–1840. Lead-glazed earthenware. L. 7". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.) The 1829 Salem pottery mold inventory includes two sizes of ducks but does not specify the function of the final forms.

Sauceboat or butterboat mold, Salem, North Carolina, 1780–1829. Plaster. L. 9". (Courtesy, Wachovia Historical Society.)

Teapot spout and lid molds, Salem, North Carolina. 1800–1830. Plaster. L. of spout mold 5 1/4". (Courtesy, Wachovia Historical Society.)

Teapot spout mold, Salem or Bethabara, North Carolina, 1786–1820. Plaster. L. 5 3/4". (Courtesy, Wachovia Historical Society.)

Cake molds, Salem, North Carolina, 1820–1850. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. of mold on left 9 1/2". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.) Cake molds, a term not used in the pottery inventories, were probably counted among the hundreds of pans recorded each year in a variety of sizes.

Mushmelon mold, Salem, North Carolina, 1810–1829. Plaster. L. 5 1/2". (Courtesy, Wachovia Historical Society.) The small size of this mold suggests that the mushmelon was produced as a small bottle or caster.

Tile stove, Salem, North Carolina, 1772–1800. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 49". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens; photo, Wesley Stewart.)

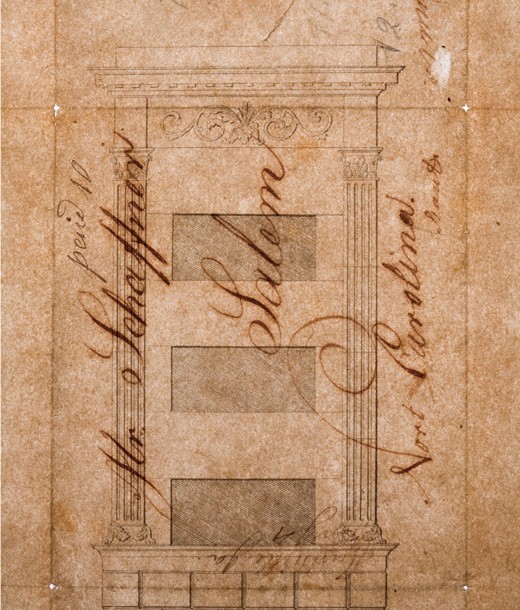

Stove pattern, Bonn, Germany, 1833–1862. Ink on paper. 16 1/2 x 10". (Courtesy, Wachovia Historical Society.)

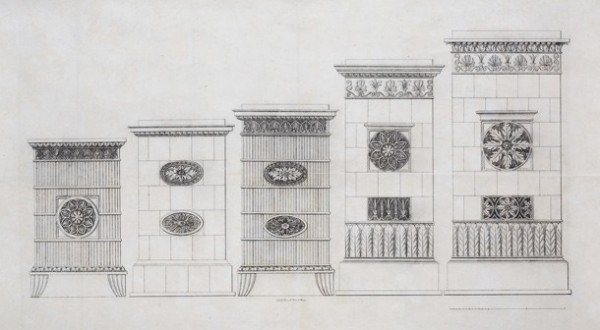

Stove patterns, Germany, 1830–1860. Ink on paper. 8 x 10". (Courtesy, Wachovia Historical Society.)

Detail of a stove pattern illustrated in fig. 56 with a bisque-fired stove molding, Salem, North Carolina, 1834–1850. (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens [molding].)

Tile stove, attributed to Heinrich SchaVner, Salem, North Carolina, 1830–1850. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 69". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens; photo, Wesley Stewart.)

Turkey mold, Salem, North Carolina, 1806–1829. Plaster. L. 9 1/2". (Courtesy, Wachovia Historical Society.) “Turkeys” first appear on the 1806 Salem pottery inventory, but there is no description of their function. The 1820 inventory lists “Turkey Flower Pots.”

Flowerpot, Heinrich Schaffner, Salem, North Carolina, 1830–1860. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 5". (Private collection.)

Lion’s-head mold, Salem, North Carolina, 1850–1870. Plaster. H. 5". (Courtesy, Wachovia Historical Society.)

Moravian potters in North Carolina made press-molded earthenware for more than one hundred and twenty-five years. The range of forms documented by surviving objects, molds, and references in pottery inventories is far greater than that of any contemporary American ceramic tradition. From smoking pipes to stove tiles, the Moravian potters at Bethabara and Salem expanded the production of press-molded earthenware to include fine table- and teaware in the "English Fabrique," figural bottles (figs. 1, 2) and casters, nonfigural bottles, and toys.[1] Although itinerant craftsmen who passed through Salem between 1773 and 1794 introduced new forms and technologies, Moravian potter Rudolph Christ was largely responsible for the success of most new endeavors at the pottery. His commitment to the production of press-molded wares during his tenure as master allowed the potteries at Bethabara (1786-1789) and Salem (1789-1821) to adapt to changing demands in the marketplace and remain viable well into the 1870s.

The Earliest Press-Molded Pottery

The first Moravian potter to make press-molded earthenware in North Carolina was Gottfried Aust. Although little is known about his early career other than his apprenticeship with Andreas Dober at Herrnhut, Saxony, and his brief tenure at the Moravian pottery in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, Aust probably learned to make press-molded smoking pipes and stove tiles before immigrating to America. He left Bethlehem in October 1755 to establish a pottery at Bethabara, North Carolina, the initial settlement on a 100,000-acre tract of land the Moravians called Wachovia. In December the following year he began to make smoking pipes (fig. 3), presumably using a press and molds he had brought from Bethlehem.[2] Because of their small size and ease of transport, the market for pipes was vast. Most of the examples recovered at Moravian sites have bowls decorated with flutes or Indian heads with baroque scrolls and leafage. All were fired in circular saggers and suspended on removable clay pins.

Most of the press-molded tiles made by Moravian potters were for stoves commissioned for public buildings and houses in and around Wachovia. Aust began producing stove tiles in the winter of 1756. According to the "Memorabilia of Outside Affairs," those examples were for stoves “he set up . . . in the Gemein Haus and Brothers House" at Bethabara.[3] Although neither stove survives, tiles recovered at Aust's site shed light on the manufacturing and assembly techniques used by him and later Moravian potters (fig. 4).

Aust made the flat tiles for the sides and ends of stoves by pressing rolled sheets of clay into molds (figs. 5, 6). After trimming the waist and removing the impressed slab, he set the tiles aside on pieces of coarse fabric to dry.[4] Once the clay hardened enough to be handled, he added clay flanges to the back of each tile. The flanges allow the tiles to be set into clay mortar, which hardens when the stove is first fired and serves as a thermal barrier against loss of heat. Other components, such as feet and cornice, waist, and base molding sections, were pressed in much the same manner. Because of the number of parts and the labor required to assemble them, tile stoves were the most expensive objects produced by Wachovia potters. In February 1782 Stephen Moore of Orange County, North Carolina, paid £3.19.3 for a stove comprising "38 tiles, 24 mouldings, and 14 Flatt Plates."[5]

Tile stoves made by Moravian potters in North Carolina were either unglazed or glazed one color (fig. 7) or decorated to simulate marble or stone (fig. 5).[6] Decorative arts scholar John Bivins has suggested that Aust brought patterns with him when he relocated from Bethlehem in 1755, and indeed the design on the stove tile illustrated in figure 5—one of several patterns in use between 1756 and the mid-nineteenth century—is similar to one found on an iron plate on a stove in Bethlehem.[7]

Early Press-Molded Table- and Teaware

Aust continued to make stove tiles and pipes after moving the pottery from Bethabara to Salem in the summer of 1771 but did not produce other types of press-molded ware until 1773. In December of that year, he received permission from the Aufseher Collegium to hire "a stranger journeyman potter by the name of [William] Ellis," who agreed to teach Aust "about the glazing and firing Queens Ware" and supervise the construction of a suitable kiln for it.[8] As a Staffordshire potter who had previously worked with John Bartlam in Charleston, South Carolina, Ellis understood the nuances of creamware manufacture, which included lathe turning, slip casting, and press molding. Five months after the itinerant's arrival, Wachovia administrator Frederic William Marshall reported that Ellis had completed his instruction and made a successful firing of both creamware and stoneware. Marshall also added that "these wares now have to be made on . . . molds . . . and are not turned on a potter's wheel by hand."[9]

The use of molds for the production of tea- and tableware continued long after Ellis left Salem in 1774. Although inventories of the pottery taken between 1774 and 1779 are sketchy at best, those from later years tend to be significantly more detailed. Aust's 1780 inventory listed "3 pipe forms," "12 tile molds," and 12 "plate molds made of clay."[10] He apparently used the term form to distinguish two-part molds from one-piece molds. The surviving plate and dish molds are plaster or earthenware negatives (figs. 8, 9) cast from positive models. To compensate for shrinkage of clay during drying, molds of this type had to be approximately 10 percent oversize.

Previous scholars have postulated that the surviving plaster molds were cast from wood models and that Christ's tenure in Valentine Beck's gunsmith shop at Salem gave him the skills necessary to carve patterns of delicate feathered edges, rococo scrolls, flowers, and leaves.[11] Those theories are problematic for at least two reasons. First, turned-wood models for dishes, plates, and comparable forms shrink across the grain, so it is far more likely that Moravian potters used clay, ceramic, or metal models, which would not change dimensionally. Second, the production of models like the one used to make a sauceboat mold recovered at Christ's first Bethabara pottery (fig. 10) was particularly demanding because there could be no undercuts in the carving. Christ worked in Beck's shop for only a year; it is doubtful that a novice apprentice would have been taught how to carve models suitable for casting.

Ellis might have brought some models to Salem and shown the Moravians how to use ceramic and pewter forms to manufacture plaster molds. Clearly he taught Aust and Christ how to process clay for "fine pottery," a phrase the Moravians used to describe press-molded earthenware and stoneware in the English taste. That type of pottery could not "be manufactured with the rough [thrown utilitarian and slip-decorated] pottery because the finest grain of sand that comes into the white clay . . . will do great damage."[12] The physical separation required for the manufacture of these two classes of ware became even more imperative owing to the turbulent relationship between Aust and his principal journeyman, Rudolph Christ. In March 1782 the Aufseher Collegium persuaded the two men to enter into a contract assigning the production of "rough pottery" to Aust and "fine pottery" to Christ. The contract remained in effect until February 1786, when Christ established his own pottery at Bethabara.[13]

The variety of press-molded forms Christ made at Bethabara was greater than that produced during Aust's tenure as master of the Salem pottery. For example, inventories of the Salem pottery taken between 1780 and 1788 consistently list twelve stove tile molds.[14] By contrast, we know that Rudolph Christ, who moved from Bethabara to become master of the Salem pottery after Aust's death in 1788, brought twenty tile molds with him and produced a greater variety of tiles.[15] Christ also took with him "40 plate molds," which he either made or had commissioned from a local tradesman. Among those molds was a plaster example for an octagonal dish marked "R. C / Bethabara / Jan. 6.~ / 1789" that might have been taken from a contemporary Staffordshire plate, then carved to provide crisp detail.[16] The carving would have involved little more than sharpening the edges of impressed designs muted by the glaze on the original. Gunsmiths or blacksmiths probably furnished some of the pipe molds used by Moravian potters. In 1787 Bethabara gunsmith Jacob Lash credited Christ £4 for a "Pipe Press with Moulds."[17]

Press-Molded Faience

Four years after Christ moved to Salem, an itinerant German potter named Carl Eisenberg passed through town.[18] On May 21, 1793, the governing board for the trades in Wachovia reported: "Br. Christ thinks he can learn some new things in the trade from the journeyman, and wishes to keep him for a short time." Four months later Wachovia administrator Frederic William Marshall reported that a new kiln for firing faience had been completed. Sherds recovered near the site of that kiln document the production of faience hollow ware in "sea green" glazes and press-molded plates with chinoiserie decoration and rim moldings picked out in blue.[19]

As Robert Hunter and Michelle Erickson suggest in "Making a Moravian Faience Ring Bottle" in this volume, Eisenberg appears to have been the catalyst for the Salem pottery's production of ring bottles. The 1796 inventory of the pottery lists a variety of faience glaze materials along with 133 "sack bottles," presumably another term for ring bottles. The Moravian potters had made flasks before Eisenberg's arrival, but the production techniques differed significantly from those required to throw ring bottles. Also listed in the 1796 inventory are eighty-seven "small barrels" (later referred to as "rundlets"), another form that does not appear to have been made earlier (fig. 11).

Marshall's report to the Unity Elder's Conference in 1793 alluded to one rationale behind Christ's interest in expanding the range of wares offered by the Salem pottery: "[E]ach new line [of pottery] draws new customers, and there are potters enough around us where they would otherwise go."[20] The purchase by the Salem Diacony of "plaister of paris" for the "potter's business" in April of that year suggests that Christ and his workmen were planning either to replace old molds or make new ones.[21] Given that Eisenberg is mentioned in the Moravian records one month later, it is tempting to speculate that he influenced Christ's decision to make figural bottles like those mentioned in early-nineteenth-century inventories of the Salem pottery. The large interlocking keys on surviving molds suggest familiarity with slip casting, a technology outside the North Carolina Moravian tradition.

Molded for the Marketplace

Between 1755 and 1800 the population of the piedmont significantly increased. By the turn of the century, white settlers from a variety of cultural and religious backgrounds—English-speaking Anglicans and Quakers, Scotch-Irish and Highland Scot Presbyterians, German-speaking members of the Lutheran and Reformed faiths, and Moravians—had claimed most of the improvable land.[22] These "strangers" (the Moravian term for nonmembers) and their communities represented a significant market for Christ and other Moravian potters.

Influenced by the American consumer revolution, North Carolinians of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries had the resources and inclination to acquire luxury goods.[23] This did not go unnoticed by Moravian leaders, who, although they lamented the materialism of newlyweds who aspired to amass quickly what previous generations had taken decades to accumulate, understood that their craft network had to accommodate changing demands within their own communities and beyond.[24]

As mass-produced objects, the figural bottles first made during Christ's tenure as master of the Salem pottery were perfectly suited to their time and place (fig. 12). Their design had broad cultural appeal, and no other regional potters produced comparable forms.

An approximate chronology for the introduction of specific press-molded bottle forms can be gleaned from inventories of the Salem pottery, which usually were conducted in the spring of each year.[25] Some forms might have been produced before the first inventory listing; the earliest reference to owl and squirrel bottles, for instance, is in the April 1804 inventory, but a "Squirrel bottle" was in the estate sale of Joseph Wells of Orange County, North Carolina, who had died the previous September.[26] By the same token, just because a specific bottle form is not mentioned in an inventory does not necessarily mean that its production had ceased. The earliest figural objects of a whimsical nature were the "Small barrels" mentioned in the 1796 inventory, but they were thrown forms.[27] "Turtles," which appear in the 1800 inventory, were the first press-molded figural objects made at the Salem pottery.[28]

Sundry Moulds, which Br. John F. Holland received from Rud. Christ in 1821 in trust and returned to Wm. L Benzien Sept. 18293 large turtles4 birds8 smaller turtles3 sheep5 small turtles5 dogs4 large fish2 bears4 smaller fish*1 Indian8 smaller fish2 turkeys15 smallest fish2 Ducks large7 candlesticks2 geese large4 small owls2 butter boats4 second size owls*4 flower horns1 large owl1 mushmelon4 large squirrels*1 dog pipe3 small squirrels2 social pipes13 foxes2 large turtles3 large dolls15 teapot spouts2 second size dolls*2 baskets3 third size dolls14 pickle leaves4 fourth size dolls12 tart plates5 small bottles0 sundry plate moulds5 second size bottles 726 out of date [bottles?] 14 chickens 3 chickens smaller *8 ducks and geese smale * Examples of the forms marked with an asterisk

have not been found.

Another valuable source of information is the list of press molds compiled by Moravian potter John Holland, who had worked with Christ for nearly twenty-five years and to whom the Church entrusted management of the Salem pottery following Christ's retirement in 1821.[29] Unfortunately, Holland's customers routinely complained about the quality of his goods (fig. 13), and the Aufseher Collegium noted that "only in the rarest of cases" was he able to turn a profit.[30] By 1829 Church leaders had grown tired of losing money on the enterprise and gave Holland the option of running the pottery as his own business. In reconciliation of the sale and transfer of tools and other property, Holland made a list of the molds that were in the pottery in 1821 (see below). Although some might have been damaged and discarded between 1821 and 1829, the list documents a wide range of press-molded forms introduced by Christ and includes some objects that either were never produced or are not known to have survived:

The exact disposition of these molds after Holland returned them to the Church is not known. Several examples in the collection of the Wachovia Historical Society have histories of ownership that can be traced to the Salem pottery, which suggests that they were used first by Christ, then by Holland, then by Holland's successor, Heinrich Schaffner (also spelled Shaffner).[31] Bisque-ware sherds recovered at the site of Schaffner's pottery document his production of press-molded bottles and other figural forms. Perhaps Holland returned the molds to the Church in 1829 because he did not plan to use them.

Figural Bottles, Toys, Casters, and Flowerpots

In many instances, the design sources for Moravian press-molded bottles are obscure. The molds for turtle bottles appear to have been taken from natural specimens (fig. 14).[32] Known for their longevity and ability to retreat from danger by withdrawing into their own shell, turtles have fascinated man since ancient times. They figure prominently in the myths and legends of many cultures and are represented in effigies, effigy pipes, Indian mounds, and graphic depictions.[33] Some Native American tribes, such as the Catawba and Cherokee, associate the turtle with creation and long life.[34] The Native American myth of the world being supported on a turtle's back explains why many tribes referred to North America as "Turtle Island."[35]

The Moravians interacted with Native Americans in North Carolina and Georgia on a regular basis. Catawba Indians were frequent visitors to Salem, and they apparently got along well with the Moravians. In 1801 the Moravians established a mission among the Cherokee at Springplace, Georgia, and worked with the Creek Indians at Benjamin Hawkins's outpost on the Flint River beginning in 1807.[36] In 1809 John Holland went to live and work among the latter tribe, joining missionaries Karsten Petersen and Christian Burkhart who had been at the Creek Agency since 1807.[37] Hawkins had asked for a Moravian potter to help the Creeks improve their wares, which he apparently found lacking.[38] Thomas John Blumer speculates that the press molds used by the Catawba to make pipes were furnished by the Moravians in the early nineteenth century.[39]

The turtle bottle illustrated in figures 15-17 suggests that Moravian and Native American stylistic influences were reciprocal. The shallow press-molded pattern on the top of its shell (fig. 17) resembles the stamped and incised designs on contemporary Indian pottery. Blumer postulates that the design on the bottle represents a sun circle, a popular Native American symbol signifying the centrality of the sun. Turtle effigies are associated with sites occupied by Native American tribes along the Mississippi River in the southeastern United States.[40]

Two different turtle bottles—occasionally referred to as "terrapins" on inventories of the Salem pottery—were available when the form was first introduced about 1800. The inventory for that year lists thirty-four turtles valued at 2s. each and thirteen at 1s. 6d. each.[41] A smaller bottle valued at 6d. appears on the 1808 inventory.[42] Like nearly all of the surviving Moravian figural bottles, turtles were coated in white slip, then glazed. Recorded colors include green, brown, and combinations of green and purplish black applied on English creamware to mimic tortoiseshell glazes. As is the case with all Moravian figural bottles, turtles are not glazed on the inside, suggesting they were intended for the storage of dry goods or for decoration, not for the storage of liquids.

Another figural form likely inspired by contact with Native Americans was the so-called Indian. "1/2 doz. Indians @ 120/" are listed in the 1806 Salem pottery inventory, one year before Petersen and Burkhart went to work among the Creeks.[43] Unfortunately, neither the mold used to produce it nor intact examples or archaeological fragments of the Indian form are known. Although it is impossible to determine whether the ceramic Indians were bottles, casters, or purely decorative objects, they were the most expensive figures made at the Salem pottery. At 10s. each, Indians cost more than twice any other figural object listed on the 1806 inventory, which included squirrels, owls, turkeys, geese, terrapins (turtles), and fish.[44] One Indian mold appears on Holland's list and a single example of the form appears in the 1829 pottery inventory (see page 113).

Some of the press-molded bottles made by Christ and his successors have cognates in Staffordshire ware (fig. 18), but there is no evidence that the Moravian examples were copied directly from contemporary English figures. Two basic types of the Moravian squirrel bottle form survive: one stands erect and typically clasps a nut between its front paws (fig. 19); the other leans slightly forward with its chin elevated, as though startled by a noise (fig. 20). These two models are probably reflected in the 1806 pottery inventory, which lists ninety-six squirrel bottles at 3s. 6d. each and forty-five at 2s. each.[45] Several variations of the upright pattern are known, including examples with the spout attached to the tail. Other differences can be noted in the molding and orientation of the arms and the size of the nut (if present).

Two different owl bottle forms can be accounted for in the 1806 inventory, which lists one example priced at 3s. 6d. and another one, presumably larger, at 5s. each.[46] The bottles shown in figures 21 and 22 represent two models, although both have oversize eyes accented with radiating flutes. British and European potters made owl jugs and figures that were both realistic and caricatured (figs. 23, 24). Only four Moravian owl bottles are known. As is the case with all standing figural forms, the owls have applied spouts and press-molded bases. The example shown in figure 22 is distinguished by having tortoiseshell colors, like English creamware owls from the 1760s and 1770s.

Bear bottles, which first appear on the 1810 inventory, might represent the Moravian alternative to English bear-baiting jugs, which were popular from the 1750s well into the nineteenth century.[47] The bear's reputation as a nuisance probably explains why the Moravian figure is depicted with a slain pig rather than a dog: on May 16, 1755, the Bethabara diarist recorded "last night a bear ate one of our best hogs."[48] Based on inventory references and surviving examples, the Salem pottery produced only one model of bear bottle (fig. 25).

Not surprisingly, the press-molded foxes made at the Salem pottery also allude to that animal's predatory nature (fig. 26). Only two examples of the form are known, both depicting the fox with a slain chicken. Inventory references suggest that the Salem pottery produced fox bottles in more than one size. The foxes listed in 1808 were valued at 1s. each, whereas those listed in 1810 were assessed at 6d. each—the same as small fish bottles.[49] The list of molds Holland received from Christ in 1821 includes "13 foxes" (see page 113) but there is no indication those examples were different in size or design.

Of all the figural bottles produced at Salem, fish survive in the greatest number. Most are glazed green on the outside (fig. 27), but examples decorated in tortoiseshell colors are known (fig. 28). Fish first appear in the April 1801 inventory of the Salem pottery valued at 1s 6p. each.[50] Three sizes were available the following year: sixty-four at 1s. 4d.; one hundred and ninety at 1s.; and one hundred thirty-six at 6d. By 1806 the pottery was producing four patterns, the number represented by surviving molds listed in Holland's 1829 inventory.

The smallest fish bottles might have been marketed as presents and toys. The example illustrated at the far right in figure 27 belonged to Alethea Fluke, a Quaker who lived in Guilford County, North Carolina. When Alethea gave the bottle to her grandson in 1889, she included a note stating: "My dear old companion we have been together 86 years I now bid thee a final farewell I give it to my grand son Trenmor Coffin in my 92nd year may it remain as long in his family as it has with me 8th mo 30th 1889 Alethea Coffin."[51] Assuming that her recollection was correct, Alethea's father purchased the bottle about 1803.

The American demand for imported fancy ceramics during the first quarter of the nineteenth century presumably contributed to the popularity of the Moravian fish bottles and other figural objects made by Christ and his successors.[52] Inventories of the Salem pottery indicate that fish bottles were one of the most popular forms; the stock-in-trade on April 30, 1806, included 627 examples in four different patterns.[53] Fish bottles would have appealed to consumers who understood the significance of fish as symbols in the Judeo-Christian tradition. The fish was also a symbol of rebirth in Egyptian culture, and an Egyptian flask of about 1600 b.c. (fig. 29) is strikingly similar to the Wachovia examples. Although the Moravians attempted to establish a mission in Egypt in 1770 (and some undoubtedly were aware of the craze for Egyptiana during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries), the possibility that an ancient artifact or an illustration of one influenced Christ's production is remote.[54]

One form never specifically mentioned in any of the pottery inventories is the crayfish bottle, which was made in at least two sizes (figs. 30, 31). Since its basic shape mimics the fish bottle, it might have been counted as one of those forms. As was the case with the small turtle bottle, the molds for the crayfish appear to have been made from a natural specimen. Realistic representations of crayfish can be found on French faience as early as the sixteenth century and on English creamware from the eighteenth century. Less refined interpretations are on German pudding molds.[55] It is possible that crayfish bottles, like the turtle forms, were intended to appeal to Native Americans, some of whom believed the "mud-diver" brought sediment up from the floor of the water-covered world to create land. Only three Moravian crayfish bottles are known, two with green glaze and one with a yellowish orange glaze.[56]

During the first quarter of the nineteenth century the variety of figural objects listed in the pottery inventories expanded with each passing year. Children enjoyed press-molded wares specially designed for them: doll heads to which cloth bodies could be attached (fig. 32); birds (fig. 33); sheep (fig. 34); lions; and dogs. The "toy dogs" listed in the 1819 inventory might have been cast from plaster molds taken from an English pearlware figure (fig. 35), whereas the molds for birds and sheep—first mentioned in 1824—appear to have been produced from locally made models.[57] Also included on the 1819 inventory were one hundred and seventy-five "ladies" in three different sizes (figs. 36, 37).[58] Although designed as bottles and casters, they might also have been sold as toys.

"Chickens" (fig. 38) and "foxes," designed for dispensing spices or fine powders, first appear on the Salem pottery inventory in 1810.[59] Both forms are on the same line and, judging by the number on hand, were in considerable demand: "44 chickens @ 6d. 24 @ 6d., 158 foxes @ 6d….. 15.11.[0]." Holland's list of molds received from Christ indicates that the latter produced two sizes of chickens, but the 1810 inventory seems to indicate that they were offered at the same price.[60]

Rooster and hen figures have a long history of display in European kitchens, which helps explain why they were popular subjects for early potters. In Pennsylvania and the Shenandoah Valley region of Maryland and Virginia, potters made all sorts of birds, but most of their work is considerably later than that associated with Christ.[61] Roosters are ancient symbols of food, fertility, luck, health, prosperity, vigilance, and the beginning of a new day.[62] The Moravians might have associated them with the Passion of Christ, since the cock has symbolized the apostle Peter's denial and subsequent repentance ever since biblical times.[63] The cock also appears in seventeenth-century German woodcuts as one of the instruments of Christ's martyrdom.[64]

The most expensive bird figures made at the Salem pottery were "turkeys" and "geese." Both forms are listed on the 1806 inventory, valued at 48s. per dozen.[65] The intended use of the goose figures remains a mystery, but the 1824 pottery inventory lists "turkey flower pots" at 1s. 8d. and 4s.[66] Christ transferred "2 turkeys" to Holland in 1821, but both appear to have been the same size.[67]

Nonfigural Press-Molded Bottles

The Moravian potters made thrown flasks and bottles decades before introducing press-molded variants. The example illustrated in figure 39 is coated in slip, decorated with manganese and copper, and glazed on the inside and outside, indicating it was made to store liquids. Likely dating from the 1790s or early 1800s, it joins a small group of ring bottles associated with Carl Eisenberg as the thrown precursors to two press-molded bottles made during Christ's tenure as master. The 1819 inventory of the Salem pottery lists eighty-four eagle bottles valued at 9s. each and thirty-four at 1s. 2d. each (fig. 40).[68] Although no corresponding mold appears in Holland's 1829 list, plaster molds for two sizes survive (fig. 41).[69] Of the three known bottles, all are the same size and all have green glaze applied on a white slip. They appear to have been inspired by mold-blown glass eagle flasks, which were immensely popular during the 1810s and 1820s. The use of an eagle on the Salem examples attests to the acculturation of the Moravians, who by 1819 had developed an appreciation for American symbols and had begun incorporating them into their decorative arts.

The other nonfigural bottle attributed to the Salem pottery resembles the eagle bottle in form but has different decoration (fig. 42). Each side has a stylized flower with a central rondel with a diapered ground, radiating lozenges with diapering, and confronting scrolls with circles and dots at the end. And although it is not mentioned specifically in the inventories, this bottle might have been one of the "57 bottles" listed in the 1810 inventory or one of the "60 bottles, green" in the 1824 pottery inventory.[70]

The decoration on the bottle shown in figure 42 resembles that on some Moravian stove tiles. As John Bivins has suggested, Bethlehem carvers probably furnished models for many of the stove tiles made in Pennsylvania and Salem. None of the extant molds or tiles made at Bethabara and Salem has decoration matching that on this bottle, but a bisque-fired example bearing what Bivins refers to as the "rococo" pattern has a central flower and framework of scrolls and leaves. Comparable skills were required to carve the molds that produced that tile and the bottle shown in figure 42.[71]

Although the orientation of the decoration on the bottle suggests that the design represents a flower, if it were rotated forty-five degrees the pattern could be interpreted as a cross. An earlier, thrown earthenware flask attributed to the St. Asaph's district of Orange County (now southern Alamance County), North Carolina, has a cruciform motif with radiating fleur-de-lis trailed in slip (fig. 43).[72] It is possible that slipware designs from that area influenced Moravian pottery. Daniel Christman, a Moravian and former business associate of Christ, lived at Stinking Quarter in southern Alamance County, and ministers from Wachovia preached and baptized children in the Lutheran and German Reformed churches in the St. Asaph's district.[73]

Later Press-Molded Table- and Teaware

During the first decade of the nineteenth century Christ began introducing new press-molded table- and teaware. The 1806 inventory of the Salem pottery lists "baskets" at 24s. per dozen and two sizes of tart plates, one at 8s. per dozen and the other at 4s. per dozen (figs. 44, 45).[74] Three sizes of "pickle leaves" were inventoried the following year, molds for two of which survive (figs. 46, 47).[75] One bears Christ's initials. Both designs seem to have been inspired by English creamware and pearlware dishes. Most of the Moravian pickle dishes presumably had green glazes, like many Staffordshire examples; however, the sole surviving Wachovia "pickle leaf" has a clear lead glaze applied directly onto a pink clay body.

"Ducks," which probably functioned as either sauceboats or small tureens, were among the most sculptural tableware made at the Salem pottery. Although not listed on any inventories, a mold for the form survives, as does an intact example (fig. 48). The list of molds Holland received from Christ includes "2 Ducks large" and "8 ducks and geese smale," which suggests that at least some of the geese mentioned on earlier inventories were tureens or sauceboats as well.[76]

Molds for two conventional sauceboats survive. The example recovered at Christ's site at Bethabara is the only one originally registered with metal pins (see fig. 10). The mold for the other example, which descended in a Wachovia Moravian family, has large plaster keys (fig. 49). These two molds could be what are described as "butterboats" on Holland's 1829 list.[77] The handles for both forms would have been molded and attached separately. Several molds for teapot spouts also survive (fig. 50), including an elaborate example with rococo decoration resembling that on the archaeologically recovered mold illustrated in figure 51.

Continuation of the Press-Molded Tradition

By 1821 the Salem pottery's repertoire had grown to include a broad range of press-molded table- and teaware, more than a dozen animal forms (many in multiple sizes), flower containers, cake molds (fig. 52), and objects whose function—if any—is unknown (fig. 53). Christ's immediate successor, John Holland, proved to be a financial disaster for the pottery, and by 1826 Church leaders began searching for his replacement.[78] Twenty-one-year-old Heinrich Schaffner of Neuwied, Germany, eventually emerged as the best candidate, although in a letter to Salem's elders he expressed concerns about having the necessary skills:

Now I take it as my duty immediately to ask you what the main product of the business is, oven goods or crockery. If it is oven goods, I could not find myself more easily willing, for Ofenarbeit is the real trade which I have learned. . . . If there are other workers there who can handle the turning, then I could decide to come there.[79]

Some translators have interpreted Ofenarbeit (literally, "oven work") to mean kiln work, but Moravians regularly used the word ofen to describe press-molded tile stoves (fig. 54). Perhaps the gist of Schaffner's comment was that he had more experience making press-molded tiles and stoves than throwing pottery.

In November 1833 Schaffner came to Salem and began working as a journeyman under Holland. Five months later Schaffner received permission to sever ties with his master and establish his own pottery at another location in Salem.[80] Presumably Holland continued to operate his shop for several more years, although when he died in 1843, he had suffered declining health "for some years past."[81]

Evidence suggests that Schaffner was proficient at producing some of the press-molded items of his predecessors. Archaeologists working at his site found the base of a chicken caster and what appear to be fragments of a squirrel bottle and a fish bottle. All of these artifacts were bisque-fired and recovered just outside the opening of Schaffner's kiln.[82]

While Schaffner continued the tradition of making stove tiles, none of the stoves surviving at Salem is documented specifically as his work. A series of nine lithographs and one drawing that descended in the Schaffner family—currently in the collection of the Wachovia Historical Society— illustrates neoclassical-style tile stoves (figs. 55, 56), a number of which are inscribed "Neuwied." Some of the later stoves resemble these illustrations (figs. 57, 58) and might indeed be Schaffner products.

Press-molded flowerpots and urns also appear to have been specialties of Schaffner's pottery, although forms produced earlier may have accomplished the same function (fig. 59). He made the mold for one flowerpot using a pressed-glass goblet (fig. 60); holes in the bottom of surviving earthenware examples denote the function. Between 1837 and 1852 Francis and Louisa (Vogler) Fries acquired several examples of earthenware from Schaffner, including "1 pot for my orange tree .75" in 1841.[83] The pot must have been either large or unusually elaborate, since they paid only twenty-nine cents for two "flowerpots from Shaffner."[84] The potter's urns caught the attention of the Salem newspaper People's Press, which reported on September 18, 1857, that "Mr. Shaffner has prepared two Urns of a beautiful fit and finish [for exhibition at the fifth annual North Carolina State Fair]." Although none of Schaffner's urns has been found, examples are visible in a nineteenth-century view of his pottery (see in this volume "Salem Pottery after 1834: Henry Schaffner and Daniel Krause" by Michael O. Hartley, fig. 6), and molds for some of their components survive (fig. 61).

The story of press-molded wares in the North Carolina Moravian communities is one of innovation, adaptation, and adjustment to changing fashions and market demands. The technique of press-molding was part of the seminal oeuvre of Gottfried Aust when he established his pottery at Bethabara in 1755. A significant change occurred when Staffordshire potter William Ellis visited the Salem pottery in 1774 and introduced the Moravians to the industrial technique of press-molding used in British factories. In the 1790s another innovation occurred at the pottery, when master potter Rudolph Christ saw an opportunity to profit by supplying his customers with new products that were more decorative than functional.

The origin of the figural bottles remains one of the great mysteries. There are several possible sources of inspiration for those made by Christ and later Salem potters, although some of the forms represented in animal bottles are so universal that efforts to attribute their source to one prototype are almost pointless. In a changing consumer environment in which mass-produced objects were becoming more widely available and objects of English manufacture were especially desirable, Christ and his successors responded by making similar forms and decorative figures. Their success is conveyed not only by the thousands of press-molded figural ceramics listed on pottery inventories but by their continuing popularity.

Wachovia administrator Frederic William Marshall used the term “English Fabrique” in his January 1, 1774, report to the Aeltesten Conferenz; Bradford L. Rauschenberg, “Escape from Bartlam: The History of William Ellis of Hanley,” Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts 17, no. 2 (November 1991): 86. The earliest use of the term bottle to describe a Moravian press-molded figural form—“40 fish @ 1/4. 250 @ 1/ . 36 little bottles @ 6d . . . 16.1.4”—is in the inventory of the Salem pottery, April 30, 1806, translated and transcribed under Pottery Inventories, Old Salem Research Files (hereafter OSRF), Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts (hereafter MESDA), Winston-Salem, North Carolina. The original pottery inventories, most of which are in German, are in the Moravian Archives, Southern Province (hereafter MASP), Winston-Salem. The “little bottles” were clearly fish, since they were included on the same line and valued the same as the smallest fish bottles in the inventory of April 30, 1803, which itemizes “64 fish @ 1/4. 190 @ 1/. 136 @ 6d . . . 17.3.4. The term bottle as an identifier of press-molded figures is rare on pottery inventories before that of April 30, 1819.

For more on Gottfried Aust’s early years at Bethabara, see John Bivins Jr., The Moravian Potters in North Carolina (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina for Old Salem, Inc., 1972), pp. 16–17.

Ibid., pp. 18–20. The “Memorabilia of Outside Affairs” is part of the annual diary kept at Bethabara.

See Alain Outlaw, “The Mount Shepherd Pottery Site, Randolph County, North Carolina,” figs. 74 and 75, in this volume.

“Account of a Stove Bought 1782 & never received from Salem,” MS receipt in Bills Receipts and Vouchers P611: folder 1790–1793, MASP. According to a note on the receipt, Moore had requested that the stove be delivered to Hillsborough; however, in 1791 it was still “at the earthen factory,” paid for but unclaimed. A Stephen Moore of Orange County was a Revolutionary War hero who ultimately settled in Person County (not far from Hillsborough) after the war. It is possible that uncertainties caused by the war delayed or prevented the delivery of the stove.

In 1823 Gottleib Byham paid to install an unglazed tile stove and apply blacking; receipt to Gottleib Byham, 1823, Bills Receipts and Vouchers P611, folder 1823, MASP. The original receipt, which is in German, is incomplete. The amount paid and the issuer of the receipt are unclear.

Bivins, Moravian Potters in North Carolina, pp. 174–76.

Rauschenberg, “Escape from Bartlam,” pp. 84–86.

As quoted in ibid., p. 88.

“Inventory of the things and tools in the Pottery, by Gottfried Aust in Salem, which had occur[r]ed new in March 1780,” Pottery Inventories, OSRF.

For speculation that Christ carved molds, see Bivins, Moravian Potters in North Carolina, p. 32; and Stanley A. South, Historical Archaeology in Wachovia: Excavating Eighteenth-Century Bethabara and Moravian Pottery (New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers, 1999), pp. 279–80, 299.

As quoted in Rauschenberg, “Escape from Bartlam,” pp. 91–92.

This dispute and its resolution are discussed in Bivins, Moravian Potters in North Carolina, pp. 33–34.

See “Inventory of the things and tools in the Pottery, by Gottfried Aust in Salem, which had occur[r]ed new in March 1780” and “The Pottery in Salem, Supplies, Tools & Equipment, November 27, 1788,” Pottery Inventories, OSRF. Stoves with several different tile patterns survive.

“Finished pottery ware that Rudolph Christ brought to the Salem Pottery from Bethabara as well as what was in the pottery here and also what material and tools and equipment was here on 1st February 1789,” Pottery Inventories, OSRF.

Ibid. The mold is illustrated in this volume in Robert Hunter, “Staffordshire Ceramics in Wachovia” fig. 31, and Luke Beckerdite and Johanna Brown, “Eighteenth-Century Earthenware from North Carolina: The Moravian Tradition Reconsidered,” figs. 51, 52.

Payment for the pipe mold is documented in “Jacob Lash agreement with Samuel Stoz, 7 May 1787”; MS receipt in Bills Receipts and Vouchers P611: folder 1787–1789, MASP.

The first reference to Eisenberg by name is in the “Outlay of the Pottery 1793,” transcribed and filed under Pottery Inventories, OSRF. He received £15 for board and “a month’s wages.” Other expenses enumerated in the same document include £12.2 for “hauling stones for the kiln,” £9.4.6 for 4,100 bricks, £1.7.1 1/2 for 325 large bricks, £1.8 for 400 feet of boards, £14.8 for a roof and shed, and £5.3.4 for masonry work.

See Hunter, “Staffordshire Ceramics in Wachovia,” fig. 42, and Beckerdite and Brown, “Eighteenth-Century Earthenware from North Carolina,” fig. 60.

Frederic William Marshall, “Report to the Unity Elder’s Conference, 1793,” in Adelaide L. Fries, Records of the Moravians in North Carolina, 11 vols. (Raleigh, N.C.: Edwards & Broughton Print Co., 1922–1969), 6:2484. These volumes were compiled, partially translated, and edited by the archivist of the Southern Province of the Moravian Church. Two more volumes, edited by C. Daniel Crews and Lisa D. Bailey, were added in 2000 and 2006.

See the entry for April 30, 1793, in “Salem Diacony Journal A 1772–1800,” MASP.

For more on the British settlement of the piedmont region, see James Graham Leyburn, The Scotch-Irish: A Social History (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1962); H. Tyler Blethen and Curtis W. Wood Jr., From Ulster to Carolina: The Migration of the Scotch-Irish to Southwestern North Carolina, rev. ed. (Raleigh: North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources, 1998); Duane Gilbert Meyer, The Highland Scots of North Carolina, 1732–1776 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1961); Francis Charles Anscombe, I Have Called You Friends: The Story of Quakerism in North Carolina (Boston: Christopher Publishing House, 1959); Seth B. Hinshaw, The Carolina Quaker Experience, 1665–1985: An Interpretation (Davidson, N.C.: Briarpatch Press, 1984).

For more on the German settlement in the piedmont, see G. D. Bernheim, History of the German Settlements and of the Lutheran Church in North and South Carolina . . . (1872; repr., Baltimore: Regional Publishing, 1975); History of the Lutheran Church in North Carolina, 1803–1953, edited by Jacob L. Morgan, Bachman S. Brown, and John Hall ([S.I.]: United Evangelical Lutheran Synod of North Carolina, 1953); Daniel B. Thorp, The Moravian Community in Colonial North Carolina: Pluralism on the Southern Frontier (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1989); C. Daniel Crews, Villages of the Lord: The Moravians Come to Carolina (Winston-Salem, N.C.: Moravian Archives, 1995); C. Daniel Crews, My Name Shall Be There: The Founding of Salem(with Friedberg, Friedland) (Winston-Salem, N.C.: Moravian Archives, 1995); The Autobiography and Chronological Life of Reverend Paul Henkel (1754–1825), edited by Melvin Miller et al. (Harrisonburg, Va.: Campbell Copy Center, 2002); S. Scott Rohrer, Hope’s Promise: Religion and Acculturation in the Southern Backcountry (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2005).

For more information on the consumer revolution, see Of Consuming Interests: The Style of Life in the Eighteenth Century, edited by Cary Carson, Ronald HoVman, and Peter J. Albert (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia for the United States Capitol Historical Society, 1994); and T. H. Breen, The Marketplace of Revolution: How Consumer Politics Shaped American Independence (New York: Oxford University Press, 2004).

Minutes of the Aufseher Collegium, June 13, 1780, transcribed and filed under Personnel and Subjects, OSRF.

An inventory is not necessarily representative of what the pottery had on hand throughout the year. Some pieces might have been manufactured seasonally, with quantities declining in the spring. Several inventories mention tile molds, for example, but the only inventory references to ceramic tiles or stoves during Christ’s tenure as master of the Salem pottery are outstanding debts for previously installed stoves, or “ovens” as the Moravians called them. The pottery inventories for 1780 and 1781 include an outstanding debt for a stove installed in the “English Schoolhouse in Hope.” Because stoves were expensive commissioned objects, there would have been no reason to maintain a stockpile of finished tiles.

Inventory of the Salem pottery, April 30, 1804, OSRF. Orange County Records, vol. 14, Inventories and Accounts of Sales, 1800–1808, edited by William Doub Bennett, 18 vols. (Raleigh, N.C.: Privately published, 1995), p. 86.

Inventory of the Salem pottery, April 30, 1796, OSRF.

Inventory of the Salem pottery, April 30, 1800, OSRF.

File R: 701, MASP; see page 113 herein.

Minutes of the Aufseher Collegium, May 29, 1826; May 12, 1828; and June 16, 1828, OSRF.

The Wachovia Historical Society (hereafter cited WHS) collection is maintained and administered by Old Salem Museums & Gardens. Accession records maintained by the WHS occasionally list sources.

Both sections of the mold for the small turtle bottle appear to have been cast from a live turtle, whereas only the bottom section of the other mold was taken from life.

Susan C. Power, Early Art of the Southeastern Indians: Feathered Serpents & Winged Beings (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2004), pp. 177–79, 191; Eugene Garfield, “The Turtle: A Most Ancient Mystery. Part 1. Its Role in Art, Literature, and Mythology,” Current Comments 39 (September 29, 1986): 3–7, available online at www.garfield.library.upenn.edu/essays/v9p293y1986.pdf (accessed August 15, 2009).

For variations of these myths, see David Adams Leeming and Jake Page, The Mythology of Native North America (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1998); and www.firstpeople.us/FP-Html-Legends/Legends-AB.html.

Leeming and Page, Mythology of Native North America.

John A. Burrison, Brothers in Clay: The Story of Georgia Folk Pottery (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1983), pp. 108–10.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Thomas John Blumer, Catawba Indian Pottery: The Survival of a Folk Tradition (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2004), p. 7.

Telephone conversation between the author and Thomas John Blumer, November 11, 2008. Although Blumer has not identified any eighteenth- or early-nineteenth-century turtle eYgies, and I have been unsuccessful in locating any pre-nineteenth-century examples in museum collections, in a conversation I had with Blumer on November 11, 2008, he agreed that the Catawba making the eYgies in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries were probably imitating a traditional art rather than inventing a new form. Blumer expresses his opinion that turtle eYgy pipes made in the late nineteenth century were probably inspired by traditional examples made much earlier but of which there are no extant examples. Blumer, Catawba Indian Pottery, pp. 182–83. For a turtle effigy vessel dating ca. 1200–1400, see Power, Early Art of the Southeastern Indians, p. 179.

Inventory of the Salem pottery, April 30, 1800, OSRF. For the term terrapin, see the inventory for April 30, 1806.

Inventory of the Salem pottery, April 30, 1808, OSRF.

Inventory of the Salem pottery, April 30, 1806 (quoted in Burrison, Brothers in Clay, pp. 108–10).

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Inventory of the Salem pottery, April 30, 1810, OSRF. Bear baiting was a rather gruesome sport, popular for centuries, in which a bear was chained and dogs were released to attack it.

The following October, the Bethabara community decided to kill ten of its pigs because they were expensive to feed and often fell prey to “wild-cats . . . foxes . . . wolves . . . and bears”; Fries, Records of the Moravians, 1:128, 139.

Inventory of the Salem pottery, April 30, 1808, and April 30, 1810, OSRF.

Inventory of the Salem pottery, April 30, 1801, 1802, and 1806, OSRF.

Handwritten note that came with a fish bottle (acc. no. 5328) when it was purchased for the Toy Museum at Old Salem Museums & Gardens in 2007.

Sumpter T. Priddy, American Fancy: Exuberance in the Arts, 1790–1840 (Milwaukee, Wis.: Chipstone Foundation, 2004), pp. xxv, 183.

Inventory of the Salem pottery, April 30, 1806, OSRF.

The Moravians sent pastor John Antes to Egypt in 1770. This effort proved to be unsuccessful for the spread of the Gospel and quite traumatic for Antes, who was tortured by followers of Ottoman offcial Osman Bey in 1779. Antes returned to Europe by 1782. Although he composed several pieces of music while in Egypt, nothing is known of his impressions of the arts or culture of the region. For more on Antes, see www.dramonline.org/albums/john-antes-string-trios-and-johann-friedric-peter-string-quintets/notes (accessed August 12, 2009).

In contrast, Napoleon’s Egpytian campaign of the late eighteenth century captured the imagination of the world. While the mysteries of Egypt had fascinated the West for centuries, Baron Dominique Vivant Denon’s Voyage dans la Basse et la Haute Égypte, pendant les Campagnes du Gënéral Bonaparte, 3 vols. (Paris: P. Didiot, 1802), was the first publication to document Egyptian architecture as a result of Napoleon’s presence there. The 21-volume Description de l’Égypte (1809–1828), which included the findings of scholars Napoleon had hired to accompany his expedition to Egypt, added dramatically to the material Denon presented and is credited with the explosion of interest in Egyptian culture and motifs in Europe and America in the nineteenth century. See James Stevens Curl, The Egyptian Revival: Ancient Egypt as an Inspiration for Design Motifs in the West (London and New York: Routledge, 2005), pp. 204–5.

A pudding mold of this type is illustrated in Gerhard Kaufmann, North German Folk Pottery of the 17th to the 20th Centuries ([Washington, D.C.]: International Exhibitions Foundation, 1979), p. 53.

Leeming and Page, Mythology of Native North America, p. 87. The crayfish was also the earliest zodiac symbol for Cancer. It is depicted on a medieval woodcut, in a band of zodiac symbols surrounding the world, which Christ holds in his left hand. The woodcut is illustrated in Dorothy Alexander and Walter L. Strauss, The German Single-Leaf Woodcut, 1600–1700: A Pictorial Catalogue, 2 vols. (New York: Abrais Books, 1977), 1:302. Given the early Christian fascination with astronomy and astrology, it is possible that the popularity of the crayfish as a subject relates to the star formation. For information on Christian interpretations of zodiac symbols and their relationship to an understanding of Christ, see www.johnpratt.com/items/ docs/lds/meridian/2005/zodiac.html. The crayfish with the yellow-orange glaze is in a private collection.

Inventory of the Salem pottery, April 30, 1819, OSRF. A photograph of the April 30, 1824, inventory is in research file S-14439, MESDA.

Inventory of the Salem pottery, April 30, 1819, OSRF.

Inventory of the Salem pottery, April 30, 1810, OSRF.

Ibid. See also page 113 herein.

For examples of chickens depicted in various decorative arts, including earthenware sculpture and needlework, see Beatrice B. Garvan, The Pennsylvania German Collection (Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1982); H. E. Comstock, The Pottery of the Shenandoah Valley Region (Winston-Salem, N.C.: Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts, 1994); and Ernst Schlee, German Folk Art (Tokyo and New York: Kodansha International, 1980).

For more on symbolism, see George Ferguson, Signs and Symbols in Christian Art (1954; repr., New York: Oxford University Press, 1961), p. 14; Juan Eduardo Cirlot, A Dictionary of Symbols (1962; repr., New York: Philosophical Library, 1971), p. 51; David Barringer, “Here Comes the Rooster: A Cocky Guide for the Graphic Designer,” Voice: AIGA Journal of Design (November 30, 2005), available online at www.aiga.org/content.cfm/here-comes-the-rooster-a-cocky-guide-for-the-graphic-designer (accessed June 19, 2009).

See John 13:38, 17:17–27.

Alexander and Strauss, German Single-Leaf Woodcut, 2:478, 536.

Inventory of the Salem pottery, April 30, 1806, OSRF.

Inventory of the Salem pottery, April 30, 1824, OSRF.

“Sundry Moulds which Br. John F. Holland received from Rud. Christ 1821 in Trust and returned to Wm Benzien in Sept. 1829.”

Inventory of the Salem pottery, April 30, 1819, OSRF.

“Sundry Moulds which Br. John F. Holland received from Rud. Christ 1821 in Trust and returned to Wm Benzien in Sept. 1829.”

Inventory of the Salem pottery, April 30, 1810, and April 30, 1824, OSRF.

Bivins, Moravian Potters in North Carolina, p. 184, fig. 168.

There is no evidence that potters in the St. Asaph’s district made press-molded earthenware.

“Stinking Quarter” was a period term used to describe the settlement near Stinking Quarter Creek and the Great Alamance Creek in what is now Alamance County, North Carolina. For additional information about the pottery from that area, see Luke Beckerdite, Johanna Brown, and Linda Carnes-McNaughton, “Slipware from the St. Asaph’s Tradition,” Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter and Beckerdite (Easthampton, Mass.: Antique Collectors’ Club, forthcoming [2010]). In 1786 Christ consigned pottery to Daniel Christman for sale in his cooper shop. The Aufseher Collegium records for November 14, 1786, state: “It was reported that Daniel Christman is selling pottery ware of Rudolph Christ in Bethabara. Br. Praezel is going to talk to him and see that he stops it.” Fries, Records of the Moravians, 2:799–800, quoting Salem Diary, May 29, 1776, and Minutes of the Aeltesten Conferenz, May 23, 1780.

Inventory of the Salem pottery, April 30, 1806, OSRF. The 1827 estate inventory of Salem cabinetmaker Friedrich Behlo lists a “basket” among other ceramics. “List of Articles at F. Behlo Sale,” North Carolina Department of Archives and Records, Raleigh, North Carolina. A more common spelling of the Behlo name in Salem records is Belo.

Inventory of the Salem pottery, April 30, 1807, OSRF.

“Sundry Moulds which Br. John F. Holland received from Rud. Christ 1821 in Trust and returned to Wm Benzien in Sept. 1829.”

Ibid.

Minutes of the Aufseher Collegium, May 29, 1826, and May 12, 1828, OSRF.

Heinrich SchaVner (Mannheim) to the Aeltesten Conferenz (Salem), October 6, 1826, MASP.

Minutes of the Aeltesten Conferenz, April 14, 1834, OSRF. Although the pottery was a privately owned business in 1834, the Church regulated how many masters worked in the various trades.

Memoir of Johann Friedrich Holland, December 25, 1843, MASP.

For more on SchaVner, see, in this volume, Michael O. Hartley, “Salem Pottery after 1834: Heinrich SchaVner and Daniel Krause.”

Photocopy of “Household Accounts of Francis and Lisetta Fries 1837–1852,” filed under Fries Family Papers, OSRF.

Ibid.