Detail of the squirrel bottles illustrated in figure 2. (Unless otherwise noted, photos by Gavin Ashworth.)

Squirrel bottles, Salem, North Carolina, 1804–1829. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 8 1/4". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens [left], Wachovia Historical Society [right].) Flying squirrels and gray squirrels were popular pets throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. John Singleton Copley’s portrait of his young half brother, Henry Pelham, depicts Henry’s pet squirrel nibbling on a nut in much the same posture as one of the Moravian bottle variants.

Pipe heads, Bethabara, North Carolina, 1756–1772. Lead-glazed earthenware and bisque-fired earthenware. H. 1 1/2". (Courtesy, Historic Bethabara Park.)

Stove tile, Bethabara or Salem, North Carolina, 1760–1800. Bisque-fired earthenware. H. 8 5/8". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens; photo, Wesley Stewart.) This tile matches sherds recovered at one of Aust’s kiln waster dumps at Bethabara.

Stove tile, Bethabara or Salem, North Carolina, 1760–1800. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 8 5/8". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Stove tile mold, Bethabara or Salem, North Carolina, 1760–1800. High-fired clay. H. 9 1/4". (Courtesy, Wachovia Historical Society.)

Stove tile, Salem, North Carolina, 1760–1800. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 10 1/2". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Plate mold, Bethabara or Salem, North Carolina, 1786–1795. High-fired clay. D. 8". (Courtesy, Wachovia Historical Society.) This mold, which might have been taken from a clay model or a pewter plate, could be one of the forty molds Christ brought from Bethabara to Salem in 1789.

Detail of the back of the mold illustrated in fig. 8.

Sauceboat mold, Bethabara, North Carolina, 1786–1789. Plaster. (Courtesy, Historic Bethabara Park.)

Barrel, Salem, North Carolina, 1790–1825. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 4 3/4". (Courtesy, Wachovia Historical Society.) In most inventories of the Salem pottery, “small barrels” are listed with the press-molded figural bottles.

Fish bottle and mold, Salem, North Carolina, 1801–1830. Lead-glazed earthenware (bottle); plaster (mold). L. of bottle 9 3/4"; L. of mold 11". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens [bottle]; Wachovia Historical Society [mold].) This mold exhibits much less wear than most of the surviving examples.

Inkwell, John Holland, Salem, North Carolina, 1810–1830. Lead-glazed earthenware. W. 5". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.) This inkwell bears Holland’s incised initials. Its design and fabrication suggest that Holland was a competent potter, despite the fact that

his wares often drew complaints from

customers.

Turtle bottle and mold, Salem, North Carolina, 1800–1850. Lead-glazed earthenware (bottle); plaster (mold). L. of bottle 7 1/4". (Courtesy, Wachovia Historical Society.)

Turtle bottle, Salem, North Carolina, 1800–1820. Lead-glazed earthenware. L. 8 1/2". (Private collection.)

The underside of the turtle bottle illustrated in fig. 15.

Detail of the top of the turtle bottle illustrated in fig. 15.

Squirrel figure, Staffordshire, England, ca. 1790–1800. Pearlware. H. 6 3/4". (Courtesy, Sotheby’s.)

Squirrel bottle, Salem, North Carolina, 1804–1829. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 8 1/2". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Squirrel bottle and mold, Salem, North Carolina, 1820–1850. Lead-glazed earthenware (bottle); plaster (mold). H. of bottle 6 1/4". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Owl bottle, Salem, North Carolina, 1804–1840. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 5 1/2". (Private collection.) The mold for this bottle is in the Wachovia Historical Society Collection at Old Salem Museums & Gardens.

Owl bottle, Salem, North Carolina, 1804–1840. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 7 3/4". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Owl figure, Staffordshire, England, 1790–1810. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 5 3/4". (Courtesy, Chipstone Foundation.)

Owl jug, Staffordshire, England, 1695–1710. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 9 1/8". (Courtesy, Chipstone Foundation.)

Bear bottle, Salem, North Carolina, 1810–1830. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 6 3/4". (Private collection.) The 1810 inventory of the Salem pottery lists forty-four bear bottles at 1s. 6d. each.

Fox bottle or caster, Salem, North Carolina, 1810–1830. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 5 1/2". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.) The base of this bottle has been restored.

Fish bottles, Salem, North Carolina, 1801–1829. Lead-glazed earthenware. L. of largest 9 3/4". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.) Although the 1819 inventory of the Salem Pottery lists fish bottles in four sizes, the 1829 mold inventory lists only three.

Fish bottle, Salem, North Carolina, 1801–1829. Lead-glazed earthenware. L. 8". (Private collection.) Slight variations among extant fish, even those of the same size, attest to the existence of multiple models and molds. The decorator of this example outlined the fish’s eyes.

Fish flask, Tell el-Yahudiya, Egypt, 1650–1550 b.c. Unglazed earthenware. L. 7 5/8". (Courtesy, Collection of University College London.)

Crayfish bottle, Salem, North Carolina, 1801–1840. Lead-glazed earthenware. L. 4 1/4". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Crayfish bottle, Salem, North Carolina, 1801–1840. Lead-glazed earthenware. L. 6 1/2". (Private collection.)

Doll head mold, Salem, North Carolina, 1820–1850. Plaster. H. 2 3/4". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.) The 1824 inventory of the Salem pottery listed 803 dolls in three sizes. They probably were not the same as the “lady bottles,” which were not listed with toys. The large number of doll heads in the inventory suggests that the pottery was making them to sell to other retail outlets.

Bird figure, Salem, North Carolina, 1810–1820. Lead-glazed earthenware. L. 2 3/4". (Courtesy, Wachovia Historical Society.) Bird figures of this type were probably intended as toys. The mold for the body of this example survives. The rather indistinct features of the head suggest that it was modeled by hand rather than produced in a second mold.

Sheep head fragment, Salem, North Carolina, 1834–1860. Bisque-fired earthenware. L. 3/4". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Garden.) This fragment was recovered at the site of Heinrich Schaffner’s pottery. Sheep and birds are listed as toys in the 1824 inventory of the Salem pottery.

Dog figure, England, 1825–1835. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 1 1/2". (Private collection.) Dog figure mold, Salem, North Carolina, 1819–1850. Plaster. H. 2 1/8". (Courtesy, Wachovia Historical Society.) The mold might have been taken from an English dog figure such as the example illustrated here.

Lady bottle, Salem, North Carolina, 1806–1830. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 9 1/4". (Private collection.) Lady bottles appear in four sizes on inventories beginning in 1806.

Lady bottle, Salem, North Carolina, 1806–1830. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 5 1/2". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.) This example probably represents the smallest of the lady bottles. It has a cluster of small holes in the back and a single, larger hole in the bottom, suggesting that this object functioned as a caster. None of the larger lady bottles has small piercings.

Chicken caster, Salem, North Carolina, 1810–1850. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 4". (Private collection.)

Bottle, Salem, North Carolina, 1790–1820. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 6 1/2". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Eagle bottle, Salem, North Carolina, 1819–1830. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 5 1/2". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Eagle bottle mold, Salem, North Carolina, 1819–1830. Plaster. H. 6 1/2". (Courtesy, Wachovia Historical Society.) According to the 1819 Salem pottery inventory, eagle bottles were made in two sizes. This mold was probably for the smaller size. The larger one is oval in shape and slightly taller than the round one illustrated here, although the eagle motif is the same size on both.

Bottle, Salem, North Carolina, 1800–1830. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 6 1/2". (Courtesy, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.) This bottle was found in Randolph County, which is adjacent to Alamance County.

Flask, probably southern Alamance County, North Carolina, 1760–1790. H. 5 3/8". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Tart plate molds, Salem, North Carolina, 1806–1829. Plaster (left); high-fired clay (right). D. of left mold 6". (Courtesy, Wachovia Historical Society.)

Tart plate fragment, Salem, North Carolina, 1806–1829. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.) This fragment was excavated on one of the lots used by the Salem pottery.

Leaf dish and mold, Salem, North Carolina, 1807–1829. Lead-glazed earthenware (leaf dish); plaster (mold). L. of dish 8 1/2"; L. of mold 10 1/4". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation [dish], Wachovia Historical Society [mold]; photo, Hans Lorenz.)

Leaf dish mold, Salem or Bethabara, North Carolina, 1786–1821. L. 9 1/4". (Courtesy, Wachovia Historical Society; photo, Hans Lorenz.) The mold is marked “RC.” No dishes of this pattern have been identified.

Duck tureen or sauceboat, Salem, North Carolina, 1819–1840. Lead-glazed earthenware. L. 7". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.) The 1829 Salem pottery mold inventory includes two sizes of ducks but does not specify the function of the final forms.

Sauceboat or butterboat mold, Salem, North Carolina, 1780–1829. Plaster. L. 9". (Courtesy, Wachovia Historical Society.)

Teapot spout and lid molds, Salem, North Carolina. 1800–1830. Plaster. L. of spout mold 5 1/4". (Courtesy, Wachovia Historical Society.)

Teapot spout mold, Salem or Bethabara, North Carolina, 1786–1820. Plaster. L. 5 3/4". (Courtesy, Wachovia Historical Society.)

Cake molds, Salem, North Carolina, 1820–1850. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. of mold on left 9 1/2". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.) Cake molds, a term not used in the pottery inventories, were probably counted among the hundreds of pans recorded each year in a variety of sizes.

Mushmelon mold, Salem, North Carolina, 1810–1829. Plaster. L. 5 1/2". (Courtesy, Wachovia Historical Society.) The small size of this mold suggests that the mushmelon was produced as a small bottle or caster.

Tile stove, Salem, North Carolina, 1772–1800. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 49". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens; photo, Wesley Stewart.)

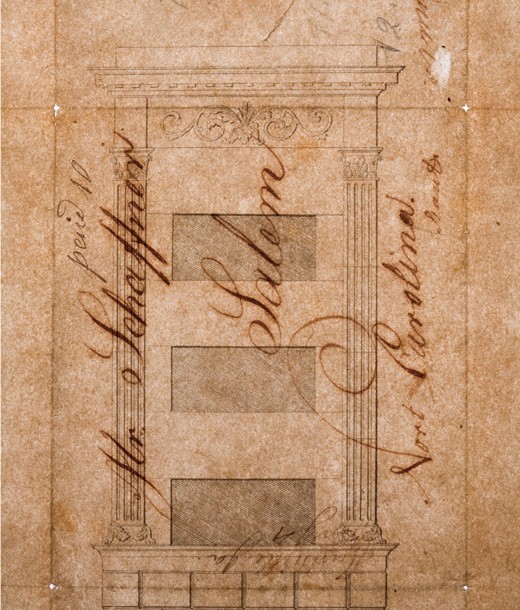

Stove pattern, Bonn, Germany, 1833–1862. Ink on paper. 16 1/2 x 10". (Courtesy, Wachovia Historical Society.)

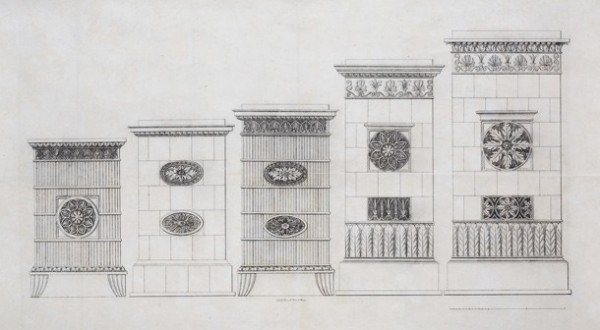

Stove patterns, Germany, 1830–1860. Ink on paper. 8 x 10". (Courtesy, Wachovia Historical Society.)

Detail of a stove pattern illustrated in fig. 56 with a bisque-fired stove molding, Salem, North Carolina, 1834–1850. (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens [molding].)

Tile stove, attributed to Heinrich SchaVner, Salem, North Carolina, 1830–1850. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 69". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens; photo, Wesley Stewart.)

Turkey mold, Salem, North Carolina, 1806–1829. Plaster. L. 9 1/2". (Courtesy, Wachovia Historical Society.) “Turkeys” first appear on the 1806 Salem pottery inventory, but there is no description of their function. The 1820 inventory lists “Turkey Flower Pots.”

Flowerpot, Heinrich Schaffner, Salem, North Carolina, 1830–1860. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 5". (Private collection.)

Lion’s-head mold, Salem, North Carolina, 1850–1870. Plaster. H. 5". (Courtesy, Wachovia Historical Society.)