National Park Service technicians assembling ceramics recovered from Jamestown, Virginia, with some of the May-Hartwell collection in the foreground, 1938. (Courtesy, National Park Service, Colonial National Historical Park. Photo # 7030.)

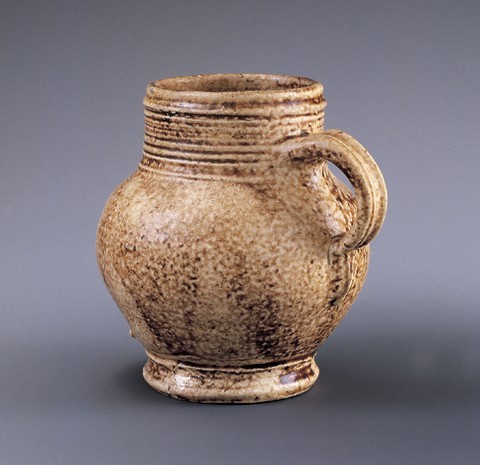

Mug, Frechen, Germany, 1660–1680. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 5 1/2". This mug with applied seal was recovered from the North Sea. The globular form and the shape can also be seen in silver and earthenware mugs of the period. Documentary and archaeological evidence suggest that similar forms were made in England as early as 1660. Characteristic of later English brown stoneware, the mug was dipped into an iron wash or slip before firing creating the rich brown mottled or freckled appearance.

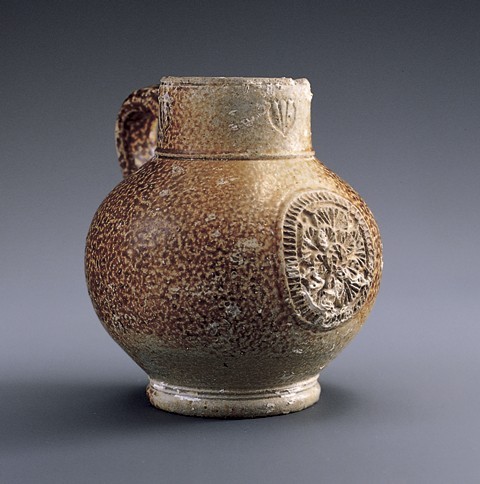

Mug, Westerwald, 1695–1702. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 5 1/4". This example has an applied portrait medallion of King William III

Mugs, London, 1700–1720. H. 4 7/8" and H. 5 3/8". The mug on the left is attributed to John Dwight’s Fulham pottery and dates ca. 1703. It has an applied Britannia medallion and an “AR” excise mark below handle. For similar examples and further reading, see Chris Green, John Dwight’s Fulham Pottery Excavations 1971–1979 (London: English Heritage, 1999), pp. 134–35 example A, and for the medallion, see p. 269. The mug on the right is ca. 1720 and has the impressed excise mark “WR.” These excise marks were required by a British Act to ensure standardization of capacities in the tavern trade of beer and ale. As the Act originated in 1700 during the reign of King William, the WR excise mark was typically used throughout the eighteenth century.

Mugs, Germany. Salt-glazed stoneware. Left: Impressed with “AR” cipher for Queen Anne (1702–1714). Right: Impressed with “GR” for King George I (1714–1727). H. 6".

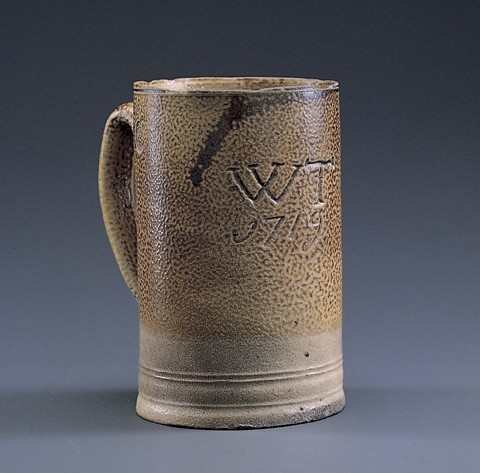

Mug, Bristol, 1719. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 5 1/2". An unusually early dated mug with an impressed “GR” excise mark in an oval. The GR marks appear to have been adopted only by stoneware manufacturers in Bristol.

Mug, Bristol, 1719. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 5 1/2". An unusually early dated mug with an impressed “GR” excise mark in an oval. The GR marks appear to have been adopted only by stoneware manufacturers in Bristol.

Mug, Fulham, 1750. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 5 1/8". A tavern mug inscribed “Jacob Morden 1750” with the sign of the rooster on its medallion.

Mug, Fulham, 1750. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 5 1/8". A tavern mug inscribed “Jacob Morden 1750” with the sign of the rooster on its medallion.

Mug, Fulham, 1750. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 5 1/8". A tavern mug inscribed “Jacob Morden 1750” with the sign of the rooster on its medallion.

A group of mugs with applied tavern signs, London. Salt-glazed stoneware. Left: H. 6 3/4. Quart tankard inscribed “Wm. Kemp in Wells, 1741” with the tavern medallion of the Golden Fleece with “WR” excise mark. Middle: Important quart tankard impressed using printer’s type “JN. Cox Bromley 1756.” This is the earliest recorded tankard using printer’s type to impress its letters and date. Previously, the earliest recorded tankard using this method was dated 1758. (See Adrian Oswald, Robin J. C. Hildyard, and R. G. Hughes, English Brown Stoneware [London: Faber & Faber Limited, 198]), p. 43.) WR excise mark and the medallion of the “house of the rising sun.” One other rising sun medallion is known on an eighteenth-century jug. Right: London quart salt-glazed stoneware tankard with the tavern sign “horses head” on its medallion. Printer’s type impressed “Thomas Deall Egham 1768.” WR excise mark.

Mugs. Salt-glazed stoneware. Left: Bristol, 1755. H. 6 3/8". This mug is incised in freehand with “Thos. Carter at ye Green Dragon Zeals Green 1755” and has an impressed GR excise mark. It is the latest dated hand incised example in the collection. Right: London, 1766. H. 4 1/4". This pint mug is impressed with printer’s type “Wm. Murrells Sulbery 1766” and has an impressed WR excise mark.

A group of mugs, Germany. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. of tallest: 5 5/8". Examples of tavern mugs of the type exported to England and the American colonies. Virtually all American archaeological sites dating between 1720 and 1760 contain fragments of such vessels.

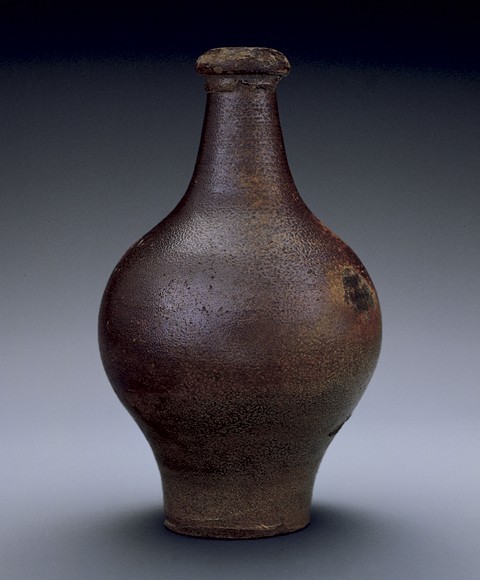

A group of bottles, Frechen, ca. 1680. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. of tallest: 9 1/4". During the seventeenth century, German “bellarmine” bottles were used throughout western Europe and North America as the containers of choice for wine, oil, and other liquids. Their ubiquitous presence is evidenced by numerous archaeological specimens found in Anglo-American contexts. These specimens are typical examples with the distinctive bearded mask and applied seals. The pronounced lips were used to fasten wires over the corks that sealed the bottles. Collectors commonly use the term bellarmine in referring to these bottles. In the period, the Germans called these jugs “bartmann” (bearded man) while the British used the term “grey beards.”

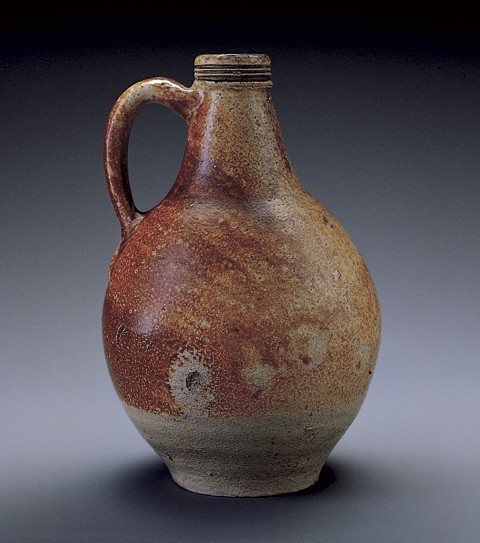

A group of bottles, probably London, 1690–1720. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. of tallest: 9 1/4". English production of stoneware bottles began in earnest in the early eighteenth century. The smaller bottles were probably used for ale and other liquors. These were eventually supplanted by the production of glass bottles. Unlike mugs and tankards, stoneware bottles were usually fired without the benefit of saggers, being stacked tightly in the kiln. Where these bottles came into contact with each other is usually evident as circular spots or indentations on the shoulders and bellies. The name “Thomas” is incised in freehand script on the left and middle bottles.

Bottle, London, ca. 1725. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 9". An elegant form in an everyday utilitarian object.

Bottle, London, ca. 1725. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 7 3/4".

Bottle, London, ca. 1725. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 7 5/8". The unique circular spot in this bottle is a result of its position in the kiln. The lack of salt-glaze within the circular area suggest that the bottle may have been resting horizontally on top of a mug or saggar.

Ink bottles, London, 1780–1820. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. of tallest: 3 1/2". These small bottles contained ink or pigments. The bottle on the left is impressed “SCOTT, 417 STRAND.” John Scott was listed in the London Directory as “water Colourman to her Majesty” at this address from ca. 1790–1839.

Bottle, London, ca. 1780. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 5 1/2". This small bottle was reputedly found in a Connecticut house cellar.

Wine bottles, England. Glass. H. of tallest: 6". The sealed bottle is inscribed “Wm. Adams 1723” and was retrieved from an English river. The bottle on the right was found in an American river. Glass bottles, whose production began in the 1660s, quickly became the standard containers for wines and related alcoholic beverages. These early examples were free-blown with the final shape being dictated by the hand of the glassblower.

A group of wine bottles, England, 1740–1760. Glass. H. of tallest: 7 1/2". These mid-eighteenth century examples were blown into a cylindrical mold in the early attempts to standardize the sizes and shapes of bottle. All three bottles have histories of being found in Virginia rivers.

Bottle, Germany, 1720–1750. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 17". Larger sized stoneware bottles were produced throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. This example has the applied bellarmine mask.

Bottle, Germany, 1720–1750. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 15". This bellarmine-type bottle was among several dozen German stoneware storage vessels recovered from the 1752 Dutch shipwreckGeldermalsen. At the time of its sinking in the East Indian Ocean, the Geldermalsen was bound for Europe carrying nearly 100,000 pieces of Chinese porcelain. These stoneware bottles appear to have been used as storage vessels for use by the ship’s crew.

Bottle, Germany, 1750–1800. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 18 1/8". Incised “4.” Generally, the bellarmine mask was not used after 1750.

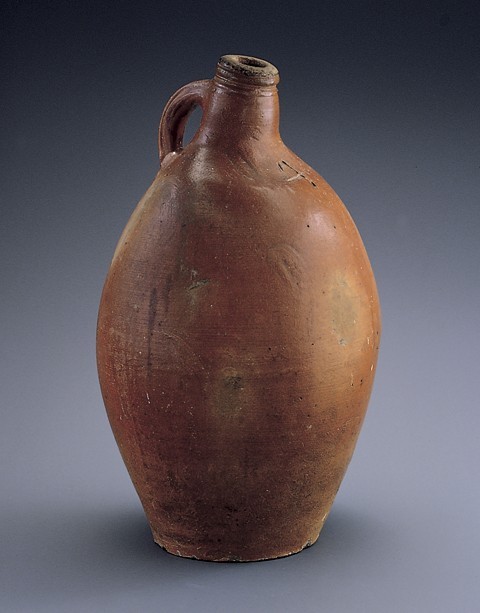

Bottle, England, probably Fulham, ca. 1720. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 15 1/4". The large English bottles, although used as containers for ale and other drink, were more likely used for oils, varnishes, and paints. Production of these larger st oneware bottles continued throughout the eighteenth century and well into the nineteenth. Contact firing spots are readily evident on this bottle.

Detail of a hand print on the jug illustrated in fig. 23. The potter who dipped this jug into the iron wash, while marring his finished product, left an indelible mark for future generations. Although most potters remain anonymous, their fingerprints are common traces left on utilitarian stonewares and earthenware

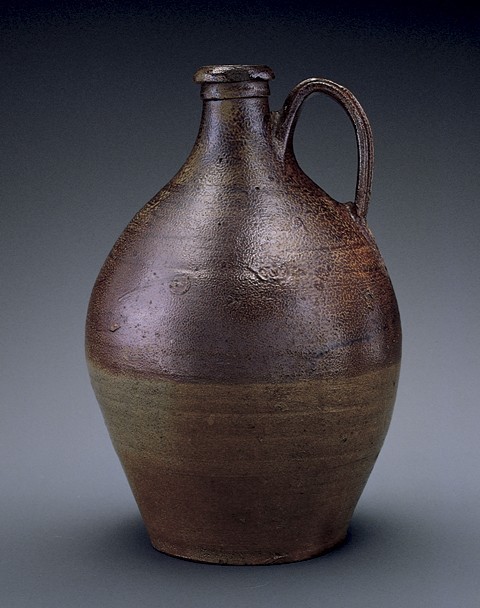

Bottle, London, ca. 1770. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 13 5/8".

Bottle, England, probably Fulham, ca. 1740–1770. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 16 1/2". This example with its missing handle was reputedly found in the York River near Gloucester, Virginia.

Bottle, London, ca. 1725–1750. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 14".

Bottle, Fulham, London, 1784–1805. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 14 3/8". Impressed “Brandram, Templeman & Jacque,” a London firm of paint suppliers or “Colour Merchants.” Several of these historically important jugs have been recorded in Virginia including two in the Colonial Williamsburg Collection. Research suggests that Brandram, Templeman & Jacque traded in Virginia and Maryland. A fragment of a similar jug was excavated at the Fulham pottery.

Detail of impressed mark on bottle illustrated in fig. 28.

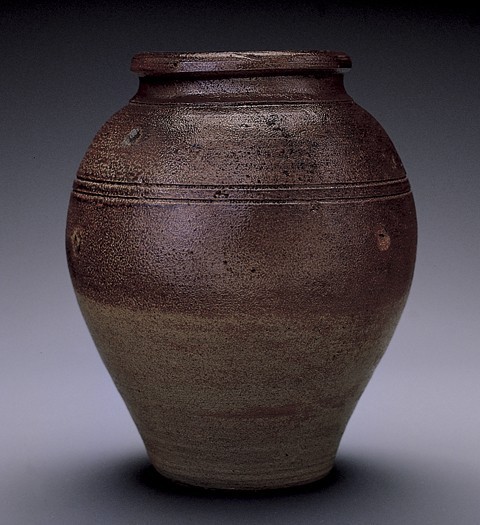

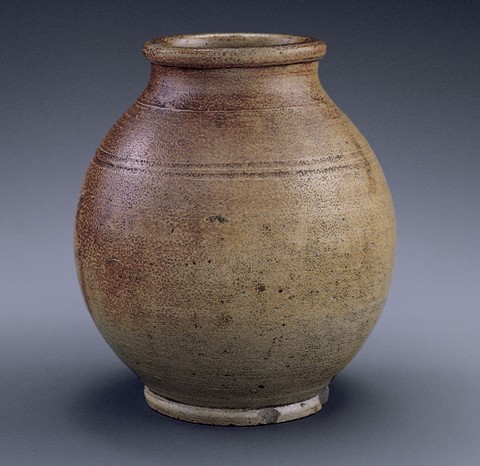

Jar, London, ca. 1720. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 7 1/2". Jars like this served as storage containers for pickles, pastes, and other perishables.

Jars, London, 1720–1750. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 6 1/2" and 10 1/8". These storage jars probably served many purposes, although they have been referred to as snuff jars.

Jar, probably London, ca. 1750. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 8". The bulbous shape of this jar is unusual.

Examples of reproductions of English brown salt-glazed stoneware, 1970–2000. H. of tallest: 8 1/2". These stonewares represent contemporary products of American and English potters supplying the considerable reproduction market for historical sites, museum shops, and living history re-enactors.

Jug, Westerwald, 1691. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 11 3/8". The incised and applied decoration includes a portrait medallion of King William and Queen Mary dated 1691. The combined use of cobalt and manganese on the body is a characteristic of late seventeenth-century Westerwald.

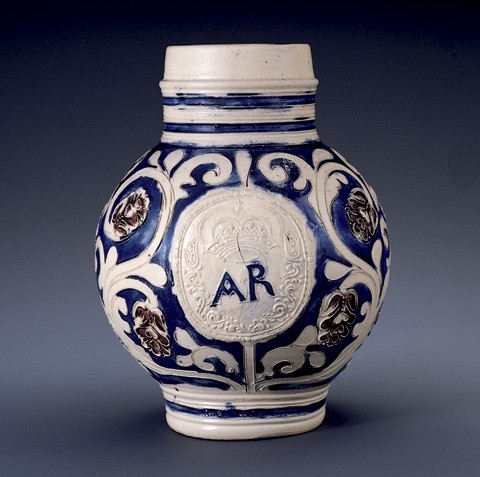

Jug, Westerwald, 1702–1714. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 8 1/8". A large example impressed with “AR” (Anne Regina), the chipher of Queen Anne. Note that a small amount of manganese is used on the body decoration.

Jugs, Westerwald, 1724 and ca. 1740. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 7 3/8". The example on the left is dated. After about 1710, the use of manganese is generally restricted to the necks of Westerwald vessels.

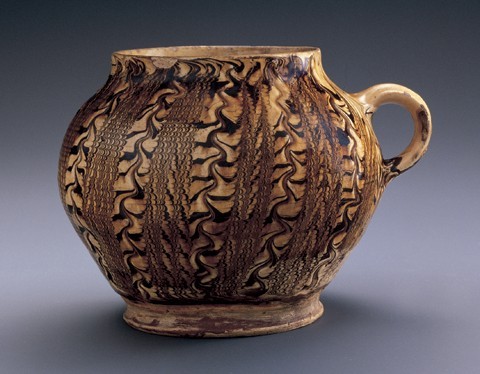

Honey pot, Staffordshire, ca. 1700. Slipware. H. 5 1/2". An early example of combed slipware with unusually fine patterning. Fragments of English slipware are among the most ceramic types found on American colonial archaeological sites and must have been used in nearly every household. The early slipwares of this type typically exhibit more care and better control in the application of the slip decoration than later examples.

Porringer, Staffordshire or Yorkshire, ca. 1730. Slipware H. 3 1/4". A later example where the quality of decoration is more debased than the example illustrated in fig. 37.

Dish, Staffordshire or Yorkshire, ca. 1750. Slipware. D. 11 1/4".

James Glenn.

I have always had a fascination with the past and sought to understand it. If we could look into the past, look into our favorite period of history, what would we see? Would we be witnessing a pivotal historical event or simply peering into the everyday life of a commoner? As we walk through museums and visit historical sites, most of us would admit that it is irresistible to think of how life might have been lived at a different time.

Much of what we know of the past is based upon the historical records of major events and the lives of the most appuent and educated personalities. Although these are strong and vital components of understanding history, they provide an incomplete picture. To see the full picture, it is necessary to understand the history and everyday lives of the common people. If the major events and personalities are the framework of our history, it is the culture of the multitudes that is its substance. Unfortunately, ways to access their lives are few. But by studying commonplace objects that have survived and, more rarely, the writings of ordinary people, we are able to get a better sense of our cultural heritage.

The late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries fall at the end of the Renaissance before the advent of industrialization that has so defined our life today. In the early part of the eighteenth century, life was still dominated by the strong traditions of the guild system. It was a period defined by the highest degree of human artisanship achieved without the advantages of complex machines. The time spent in labor to produce goods was of little regard—the emphasis was on the conservation of raw materials. Many of the goods recovered from that time show that great attention was paid to detail and artistry. The subtle but functionally unnecessary incised lines on the shoulder of a common utilitarian storage jar are but one example of this kind of detail.

Goods were meant to last long useful lives and to be enjoyed for their appearance. This touches all aspects of material production, including furniture, ironwork, leatherwork, and ceramics. But as industrialization emerged in the early nineteenth century, handmade goods begin to lose their artistry to mechanization and standardization. My collecting has been focused on gathering the humble objects used by many to try and piece together a picture of eighteenth-century life in England, as well as her American colonies.

The Beginnings of Collecting

I can never remember a time when I didn’t collect. It began as an unconscious activity early in childhood. Like so many things in life, I didn’t know where this passion would take me.

As a boy raised on the south side of Virginia, I found numerous Indian artifacts in almost every field and stream bed. American Civil War relics were constantly found near my mother’s family farm, where Lee and Grant engaged in their last titanic struggle. I loved to comb through the wreckage of my father’s eighteenth-century ancestral home that burned in 1932 and subsequently was abandoned. As these sites yielded various relics of the past, I was too young to understand their function or importance. Many were used as skipping stones in the nearby creek. As I grew older, I was filled with excitement to notice the chipping that had fashioned the arrowheads and the finger impressions that molded the pottery sherds. I soon began saving everything I had previously been throwing away. Bullets, spurs, canteens, shrapnel, broken swords, and Indian relics began to adorn my room.

Whenever I found one of these field relics, I experienced a sense of awe. The thought that someone long ago had walked this very ground gave me an emotional link with the past that I had never experienced. The thought that I may be the only person to have seen these objects since they had been lost or cast aside by their owner overwhelmed me with excitement. These youthful experiences fueled my desire to collect. I was beginning to look through that window into the past, but there was much more to learn. For me collecting became a learning experience, rather than a mere function of assemblage.

Before I was in the first grade I became inspired by an uncle, who collected antique firearms. He gave me my first Civil War musket when I was six. At the age of eight, I purchased other relics, and at the age of ten, I bought my first primitive piece of furniture. It was an early Virginia pine chest held together with wrought nails and made with wooden hinges. Family members began to question my motives when I dragged this chest into my room with its two hundred years of soil and grime attached.

I was constantly inspired by the numerous trips to nearby Jamestown and Colonial Williamsburg. Some of my fondest memories were of playing on the cannon in front of the Magazine and walking through the houses that line Duke of Gloucester Street. I admired the reconstructed settlement at Jamestown. It was there that I first became interested in the architecture and the construction techniques our forefathers had used. My interest in early colonial life was strengthened by family trips to Boston, Massachusetts, and Charleston, South Carolina. I coerced my parents into stopping at every museum and antique shop that we passed. I never gave up the hope that I could convert them into collecting antiques, as their financial position could have afforded all of the great items that had captivated my attention. Unfortunately, I soon realized this was an undertaking I would have to assume myself. In contrast, my daughters Christie and Raleigh have taken more than an active interest in my collecting.

During this time every aspect of eighteenth-century life became fascinating to me. From politics to purses, textiles to tools, chamber music to military tactics, I wanted to understand the entire spectrum. I began to wonder about the people that made and used these objects. What were their lives like? Who were their families? What was their form of entertainment? What did they consume? What were their favorite foods? How did they travel? What was their sense of economy? How were their homes different from ours today? How did they cook? What kind of tools did they have? Where would they get them? At a very young age, I was filled with so many questions and had no idea where to find the answers. The history that I began to read as a young student did not address the majority of my questions.

Up to this point, the history I had studied was the typical assortment of dates, places, and important events. That began to change when I was invited to participate in an archaeological excavation with one of the state organizations. Being around the archaeologists and listening to their conversations, as they spoke of past finds as well as the ones they were uncovering, taught me not all questions where going to be answered by the text I had been reading in school. I realized I would need to do my own investigating and research.

During high school I became increasingly curious about the construction and development of objects as well as the people who made them. As much as I was gaining a view into the past, I was now trying to grasp some tactile historical experience by reproducing some of the pieces in my collection. Wonderful as it was to examine and place these pieces in their proper historical context, I wanted a deeper understanding of how people living in past centuries rose to the challenges of their limited technology. To test my own skills, I decided to reproduce an eighteenth-century Virginia-style long arm, well before a kit or mail order parts made building a facsimile easy.

I was also inspired by publications in archeology and other fields. From the underwater excavation of Port Royal, Jamaica, I drew many parallels between the findings there and my studies of colonial life in Virginia. I especially enjoyed publications interpreting the Williamsburg and Jamestown areas. At the same time I began to realize that exported colonial life from the European nations was somewhat homogenized no matter the location. The most enjoyable, inspiring, and influential writings were those by Ivor Noël Hume. He was the first in my experience who seemed to tell me what I wanted to know. Through him I learned that seemingly insignificant objects were in fact some of the strongest links to the past. His interpretive abilities, the way he was able to relate an unearthed object to its historical context, was unequaled. I became a fan of sorts, always waiting for the next book or article.

Other influential works included those by Wendell Garrett, Israel Sack, and Wallace Nutting. I soon found myself collecting references of all sorts, which began to form the nucleus of my personal historical library. I realized that a library was one of the most important tools and assets for a collector. I would urge anyone who is just beginning to collect to read everything you can on your subject. Talk to everyone involved in your field of interest, take notes, photographs, make measured drawings whenever possible, and save it all.

During and after college, along with collecting, I began to reproduce many of the items in my collection as well as others I viewed in museums, an occupation that fascinated me. The idea was not merely to reproduce the antique object itself but to understand and experience the actual process that might have been used. This helped me gain greater insight as to how early artisans achieved their results. There were other implications. When determining whether or not an object was genuine, repaired, or a reproduction, knowing the original process gave vital clues not found in a text book or by merely viewing a piece from a distance in a museum.

While making these reproductions, I also found myself establishing a closer bond to the artisans of long ago. But if I were going to accomplish this task properly, I would need to make many of the tools of the period and to make them in period fashion. My projects were interrupted by my Wall Street training, and the usual activities consistent with business and family. Collecting, however, always remained my favorite pastime.

For many years, I have been affiliated with a number of organizations oriented towards my various historical interests. In many ways I have found my membership with them to be as useful in gathering information as the assembly of my own library. These organizations produce written works in the form of newsletters, bulletins, and books. Meeting and talking with members results in the cross-pollination of knowledge from a multitude of diverse sources.

I joined the Artist Blacksmith Association of North America and the Florida Artist Blacksmith’s Association long after I had established my eighteenth-century style forge. Not all were as interested as was I in developing eighteenth-century items. However, there were always some within these organizations who wanted to share knowledge and skills. I produced nails, locks, cooking utensils, furniture hardware, architectural hardware, woodworking tools, and smithing tools.

As I became fond of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century leatherwork, collecting once again turned into reproducing. These interests led to my membership in the Honourable Cordwainers Company. I produced leather jacks, buckets, bottles, and shoes of the period. Likewise, my furniture building and woodworking turned into another obsession. I joined the Society of Workers of Early American Trades, the Midwest Tool Collectors, and the Early Arts and Industry Association. The pursuit of collecting stoneware has led me to a membership in the most interesting Society for Post-Medieval Archaeology. Although I have yet to attend their meeting, the Society produces a wonderful annual publication that covers a variety of discoveries of interest to the ceramics collector.

Reasons for Collecting

There are many reasons why people collect and many approaches. My collecting has been eclectic; because I started collecting at such a young age, I had no preconceived notions. In collecting and preserving those hard-to-find pre-industrial goods from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, I have two criteria. One is the material object’s place in history. The item must be judged as to how significant a role it played in the daily life of its time. The other is the history of the development of the object itself. It should have the qualities that exemplify one of the evolutionary processes in the development of its product type and class. I collect ceramics, metal, wooden and leather objects with emphasis on those used by or produced for the English and American markets during the first through third quarters of the eighteenth century. Occasionally I venture into the seventeenth century when I find objects that are necessary to explain the development of certain objects that came later or when the useful lives of the objects themselves extended into the eighteenth century.

My favorite area of ceramics is the brown stoneware first produced in the Rhineland then later produced in England. I am also keenly interested in early cobalt-decorated, Westerwald stoneware. These objects are subtle reminders of important physical changes in the way people lived. Their development facilitated the daily life of generations by making it easier to store, serve, and process foods and beverages. As necessary as they were to their time, they are relatively obscure today. They were not made for the courts of kings and queens and do not exemplify the highest art form of their day. They would most likely be found in a kitchen or a tavern, a part of the homescape of eighteenth-century life. Held in little regard, they were continuously used until destroyed or scrapped when replaced by new technologically advanced wares. As a result, these wares are relatively scarce and most of the information on them has come from archaeology.

The irony is that items made for the aristocracy were rare and expensive in their day and seldom used for their intended purpose. People would save, cherish, and gently hand them down to future generations, like any wonderful work of art. Many commemorate special events, dates, or regents. Today these objects can be easily found as long as your checkbook is nearby. Because the common and inexpensive brownwares of the day were not considered heirlooms, they were not saved, hence the search for these pieces today is particularly difficult.

Collecting Salt-glazed Stoneware

I first noticed English salt-glazed brown stoneware at Colonial Williamsburg, early in life. I never forgot it. The interiors of many original and restored structures were stocked with various mugs and storage jars. These personal items were placed on tables or inconspicuously on shelves, as if the owner had just set them down. This intimate human aspect helped breath life into an inanimate setting. Much later in life I started collecting brownware. My collecting inclination was ignited when my friend antiquarian Bill Wensel gave me my first piece.

Brown stoneware is a highly fired clay body usually gray in color. After being thrown, these wares were dipped in an iron wash to create the brown appearance. They were then fired and glazed with salt. Unlike earthenwares, stoneware was so highly fired that the material became impervious to liquids.

The technique of stoneware manufacture was perfected sometime in the late thirteenth century, in the Rhineland of Germany. These wares were much more desirable than the porous and fragile earthenwares of their time. Stoneware vessels easily became the vessels of choice when compared to their wood, leather, horn, and earthenware counterparts.

The European market for the everyday stoneware vessels grew so rapidly that it became greatly profitable. Distribution networks reached far and wide, entering the English market in the fourteenth century and mostly dominating it by the late fifteenth century. Stoneware became so widely used in England that merchants were known to import and even stockpile vast quantities in warehouses. It was then distributed among local markets.[1]

Envious of German products and profits, English potters attempted to imitate these wares. Many failed, as the secrets to successful stoneware production were closely guarded. If the process was going to be replicated, interested potters would have to discover it by numerous experiments. Although these experiments were well underway in England by the first half of the seventeenth century, the production of stoneware did not develop as quickly as that of delftware and gallipot. Toward the end of the century, the foreign monopoly was broken, and English brown stoneware was developed in London, Nottingham, Derbyshire, Burslem, and possibly Bristol.[2]

The first successful potter to do this on a commercial scale was John Dwight at his Fulham kilns. By the 1670s, Dwight’s products were given credit for raising the standard of brown stoneware in England. He even began to produce copies of the blue and purple Westerwald wares. History generally regards Dwight as the “father” of English ceramics, and his success signaled the birth of the English ceramics industry.[3]

At first, English stoneware was produced in the same style and types as the German products they intended to imitate. Stoneware bottles were turned to the same shape as the German bellarmines. Medallions were applied to the center of the body and masks were applied to the neck. Mugs, which were short and globular, were turned with reeded necks and made with a pad base. By the early eighteenth century, the English freed themselves from these imitated German forms. Bottles lost their masks and medallions. Mugs and tankards were turned in cylindrical form, which remained the style throughout the rest of the century.[4]

The growth of the tavern business in England prompted huge demand for stoneware, both imported and locally made. This demand did not simply come from the British Isles alone. The British Empire was rapidly expanding over the world. There was an especially rapid rise in population in the North American colonies, resulting in an increased demand for stoneware.

Stoneware could be produced in quantity and at little relative expense. It has been found in tavern, domestic, and military archeological sites. Stoneware has always been a valuable tool for dating the finds of archaeologists. From the tremendous amounts of stoneware unearthed, it is obvious that it was an integral part of everyday life in the eighteenth century, just as pop bottles would be today.

The story of tankards and mugs of this period is of special interest to me. Most taverns had their signs painted and hung outside their establishments. Many had them copied and added as a medallion to the front of their tankards. These panels were applied to the tankard with a sprig mold. It was not uncommon for local patrons to carry home their beverages, and even though illiteracy was common, anyone could easily identify the tavern to which the tankard belonged.

Sometimes other information was placed on the tankard, such as dates, owners’ names, and tavern locations. Tankards could exhibit one or all of these features. If the tankard were intended for commercial use, it would usually have an excise mark to indicate a full and proper measure of liquid sold. “The official English marks generally were incuse or stamped in relief with the cypher and crown within a borderless oval.”[5]

Other marks on English brown stoneware, such as dates or inscriptions, were made using two distinctively different techniques. Up to the middle of the eighteenth century, marks were incised or scratched in by hand. Beginning in the second half of that century, marks were impressed using printer’s type. As an example, the latest hand incised tankard in my collection is dated 1755, while the earliest printer’s type impressed date reads 1756. This later specimen is the earliest known brown stoneware example to exhibit a printer’s type date (see figs. 8, 9). Dated tankards and those with tavern signs applied as medallions to their bodies have been excavated in English and colonial American archaeological sites.

The gray-bodied Westerwald stoneware, with its blue cobalt decoration, continued to be made in the Rhineland and imported into England during the eighteenth century. “From about 1700, blue-gray Westerwald mugs, which combined the strength of stoneware with the decorative qualities of delftware, were specifically made for the English market.”[6] Even though the English industry was successfully producing stoneware in quantity, demand made it necessary to continue purchasing German imports. This was due to the ever-increasing growth of the tavern trade. Most were adorned with a medallion containing the initials of the current monarch on the English throne (WR King William; AR Queen Anne; GR King George I, II, III). Infrequently a portrait of the monarch, including a date, was applied to tankards and jugs, which were known to be imported until the early nineteenth century.

Trying to date these pieces is not always as obvious as reading the applied date. Dates on vessels can be commemorative. However, most evidence indicates that the date is generally very close to the date of manufacture, if not in fact the actual date of production.

Although I have a great passion for all the stoneware in my collection, be it storage jars, mugs, jugs, or tankards, the petite gorge or mug made by John Dwight around 1675 is my favorite (see fig. 1). This piece represents one of the earliest examples of the stoneware industry in England. As all collectors can appreciate the importance of this single item, it by no means completes the challenge and pursuit of other great objects.

I have tried, unsuccessfully, to acquire objects that were made in the factory of William Rogers of Yorktown, Virginia. Although the story of the Rogers factory is not well known by most collectors of ceramics, archaeological and historical research have documented it as the earliest and most important American stoneware manufactory. As the need arose for domestic suppliers, some potters attempted to take advantage of new colonial markets. William Rogers moved to the Virginia Colony where he made a wide range of earthenware and stoneware products in his Yorktown kilns from around 1720 to 1740 including brown stoneware tankards. Of the few that exist, some are almost indistinguishable from their English counterparts while others are distinctively more primitive. I have yet to find, much less acquire, an antique specimen of Rogers’ stoneware.

If and when these utilitarian objects come up for sale, the same condition standards should not be applied to them as for other types of ceramics. Almost all of these pieces were damaged in some way during their useful life. They tell a story of hard use, and we are lucky to have any at all. No one should apologize for a small amount of restoration. In some ceramic circles, however, restoration can get out of hand. I have seen entire pieces almost completely fabricated from very little original material. I personally like those pieces that are completely untouched by the restorer’s hand. I believe that the bumps and bruises tell the story of their great age. I am always amazed when people are induced to collect objects that are older than two centuries yet still want them to look freshly made. When restoration hides the record of use, something has been taken away from the object, its link to history broken.

In summary, I have found that the more common and useful the object, the better it represents the culture that produced and used it. Think of our modern world today. Which would best define our daily cultural life—a great work of ceramic art utilizing all our modern techniques of manufacturing? Or would it be the Coke bottle? I will let you decide.

Adrian Oswald, R.J.C. Hildyard, and R. G. Hughes, English Brown Stoneware 1670–1900 (London: Faber and Faber Limited, 1982), p. 18; David Gainster, personal communication.

Ibid, pp. 18–19.

David Gaimster, German Stoneware 1200–1900 (London: British Museum Press, 1997), p. 311.

Ibid., p. 312.

Malcom C. Watkins and Ivor Noël Hume, The “Poor Potter” of Yorktown (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1967), p. 92.

Gaimster, German Stoneware, p. 312.