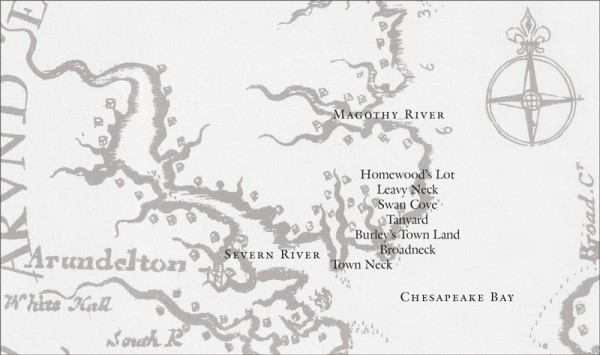

Providence settlement sites overlaid onto detail of Virginia and Maryland, map drawn by Augustine Herrmann in 1670 and published in 1673. (Private collection.)

Lost Towns Project archaeologists and volunteers conducting salvage excavations at Homewood’s Lot, 2002. (Photo, Shawn Sharpe, Lost Towns Project.)

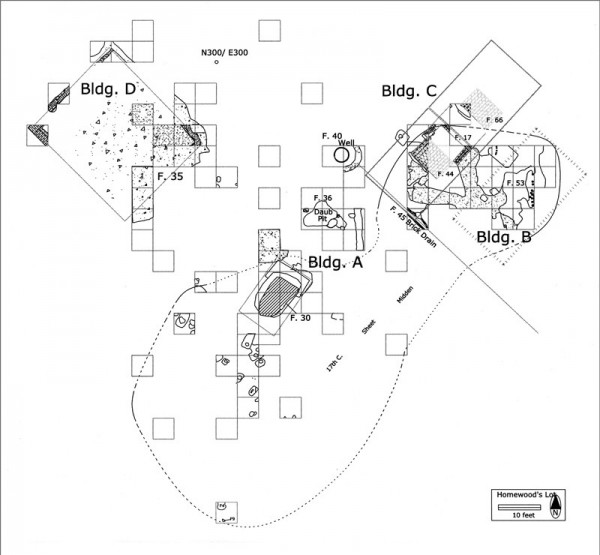

Archaeological plan view map of Homewood’s Lot, 2004. (Courtesy, Lost Towns Project.)

Archaeological profile of the cellar designated as Feature 30, Homewood’s Lot, 2002. (Photo, Al Luckenbach.)

Chart comparing temporal ranges and percentages of belly bowl and trade pipe forms recovered from archaeological sites in Anne Arundel County, Maryland, including Homewood’s Lot (18AN871).

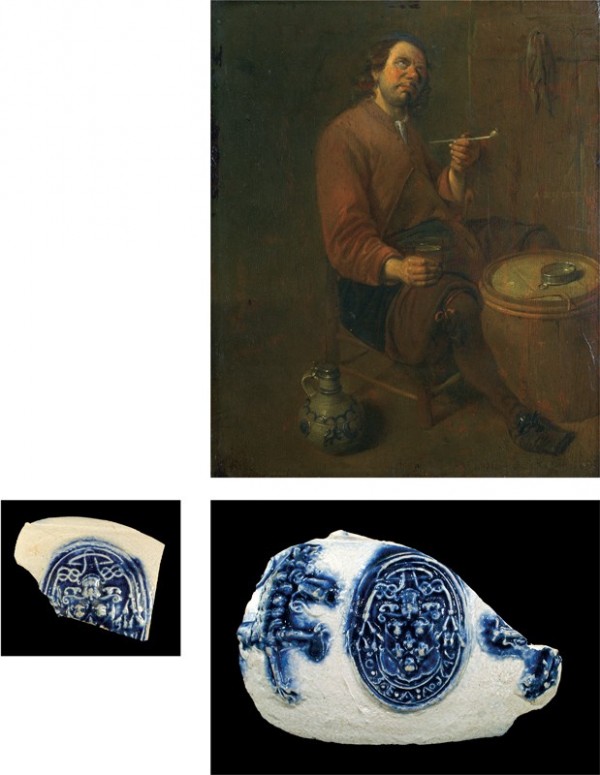

Arent(?) Diepraem, A Peasant Seated Smoking, ca. 1650. Oil on oak. 11 1/4" x 9". (Courtesy, The National Gallery, London.) The decorative elements on a Rhenish jug seen in the foreground of this painting bear a remarkable similarity to the fragments below, which were recovered from the shoreline of St. Mary’s City, Maryland (right), and Feature 30, Homewood’s Lot (left). A date of 1646 is visible (at approximately 4:00) on the medallion found at St. Mary’s City. (Courtesy, Historic St. Mary’s City.)

Detail of fragments of a colander similar to the one illustrated in fig. 8. The lead-glazed earthenware fragments are possibly Holland, ca. 1660s.

Nicholas Maes, A Girl Plucking a Duck, 1634. Oil on canvas. 23 5/8" x 26". (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art.) The colander depicted in this painting provides a suitable comparison for an overlay of several fragments from a similar vessel recovered from Feature 30, Homewood’s Lot.

Handled cup fragments, England, ca. 1660. Manganese-enriched lead-glazed earthenware. (Photo, John E. Kille.)

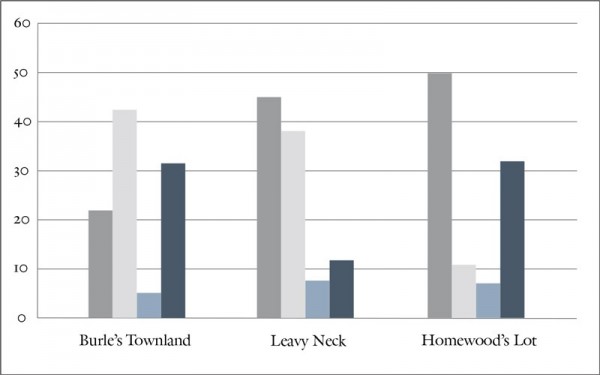

Chart comparing ceramic assemblages recovered from Burle’s Townland, Leavy Neck, and Homewood’s Lot sites, Providence, Maryland.

Mid-drip candlestick fragment, probably England, 1660s. Tin-glazed earthenware. (Photo, John E. Kille.)

Jan van der Heyden (1637–1712), Still Life with Books and a Globe, seventeenth century, Southern Netherlands (modern Belgium). Oil on panel. 8 15/16" x 10 5/8". (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art.) This painting includes a candlestick typical of the seventeenth century.

Candlestick, Southwark, probably Pickleherring, London, 1648. Tin-glazed earthenware. H. 10 3/16". (Courtesy, Victoria and Albert Museum.) This rare example is decorated with the arms of the Fishmongers’ Company and is inscribed “W / W / E / 1648.”

Handle and porringer fragments, probably England, ca. 1660s. Tin-glazed earthenware. D. of rim 5". (Photo, John E. Kille.)

Plate fragments, the Netherlands, ca. 1660s. Tin-glazed earthenware. D. 8 1/2". (Photo, John E. Kille.)

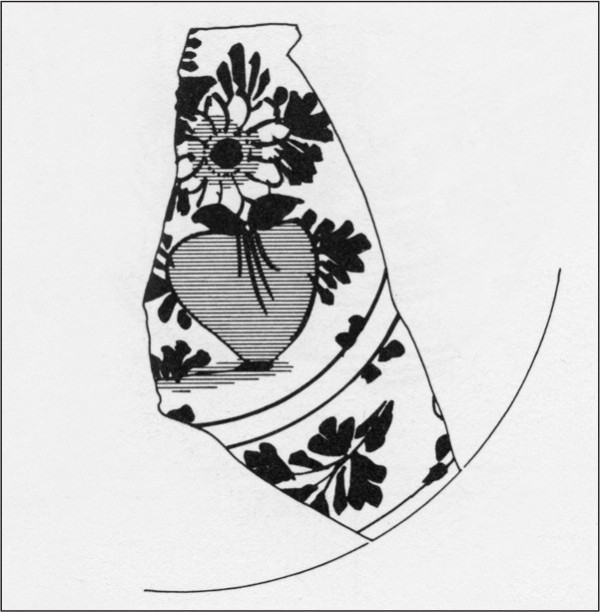

Drawing of a 17th-century tin-glazed earthenware plate attributed to Holland manufacture, illustrated in Sarah Jennings, Eighteen Centuries of Pottery from Norwich, East Anglian Archaeology Report No. 13 (Norwich, Eng.: Norwich Survey in collaboration with Norfolk Museums Service, 1981), p. 191.

Plate fragment, the Netherlands, ca. 1660s. Tin-glazed earthenware. (Photo, John E. Kille.) The extrapolated diameter of the plate is 8 1/2".

Bowl fragment, probably England, ca. 1660s. Tin-glazed earthenware. (Photo, John E. Kille.) The extrapolated diameter of the footring is 2 1/2".

Anne Arundel County’s Lost Towns Project has recovered an interesting and informative ceramic assemblage of twenty-eight vessels from a seventeenth-century homesite in present-day St. Margaret’s, Maryland. Discarded circa 1665 in a cellar measuring 10 feet by 6 feet, these vessels show an unusual bias toward sophisticated tin-glazed earthenwares as well as Dutch influence.

Homewood’s Lot, designated 18AN871, is located off Whitehall Creek near the Chesapeake Bay in Anne Arundel County, Maryland. The site represents the remains of the circa 1650 occupation by Quaker planter Thomas Homewood and, for another century, his descendants. It is one of eight known sites associated with the 1649 Puritan town called Providence, the first European settlement in the county (fig. 1).[1] Between 1999 and 2002 a series of archaeological salvage excavations at this location, conducted by Anne Arundel County’s Lost Towns Project (fig. 2), uncovered a number of structures, including two dating from the 1650s and 1660s and two built in the early eighteenth century. The latter two dwellings show evidence of abandonment and demolition circa 1770.[2]

The earliest structure, designated Homewood’s A, was an unusually small building constructed with sills resting on a highly degraded, native ironstone foundation or piers. It had an external wattle-and-daub chimney on its northern elevation and a storage cellar, designated as Feature 30. Compared with the other structures found at Homewood’s Lot and other Providence sites, this heated building was tiny, measuring approximately 16 feet by 10 feet (fig. 3). The stratigraphic profile of the cellar fill displayed a readily visible alternating series of discarded trash and reddish fireplace ash (fig. 4). The discovery of a remarkable assortment of mid-seventeenth-century ceramic vessels within this tightly dated and undisturbed context provides an unusually detailed glimpse of European ceramic ware consumption in Providence.

The artifact assemblage recovered from the cellar indicates that the structure probably was built during the initial settlement, circa 1650, although it should be noted that construction debris was also found that does not appear to be related to the building of this structure. Green-glazed Dutch floor tiles, bricks, and a 1661 dated window lead suggest that Homewood A was occupied during the construction of another, more elaborate dwelling nearby (Homewood B), presumably during the early 1660s.[3]

The most obvious diagnostic artifact from the cellar is the window lead, which provides a useful alternative to dating from the ceramic assemblage. An analysis of the bore diameters of clay tobacco pipes produced relative dates of 1654 and 1659.[4] Analysis of the pipes recovered from the plow zone soils immediately over Feature 30 produced dates of 1664 and 1666, which are in closer accord to the fill date being conjectured here.

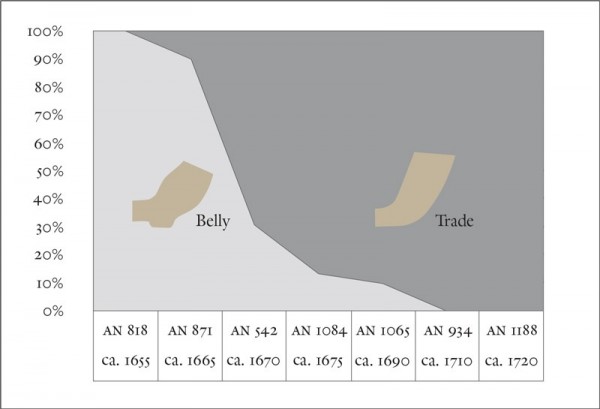

The authors believe, however, that ceramic tobacco pipe bowl forms provide a much better diagnostic indicator for temporal placement than do stem bores. Based mainly on the ratio of belly bowls to trade pipes, analysis of pipe bowl forms suggests a mid-to-late-1660s deposit fill (fig. 5), which corresponds nicely to the 1661 dated window lead.[5]

Ceramic Vessels

The excavation of the cellar produced an unusual array of different types of ceramic vessels, including several interesting examples of white-glazed and decorated delftware, Rhenish blue-and-gray salt-glazed stoneware, and small amounts of North Devon and Staffordshire wares. For dating purposes, it is the absence of certain ceramic wares that is most significant. For example, English brown stoneware, manganese-mottled earthenware, and combed Staffordshire slipwares as well as the later white salt-glazed stonewares, all of which are common in other Providence sites, were not evident in the cellar feature. These other ceramic types are usually found in post-1680 contexts, and their absence in the cellar suggests that it had been filled before 1680.

Stoneware

Rhenish stoneware with both brown and blue-and-gray finishes is usually quite common on Providence sites, occasionally reaching 7.5 percent of assemblages. Yet sherds from only two vessels of this type were recovered from Feature 30: a single sherd of Rhenish brown stoneware, and thirty-one sherds of Rhenish blue-and-gray stoneware from a single jug. Among the surviving pieces of the jug, and perhaps the most interesting stoneware find, was a distinctive medallion (fig. 6). An identical medallion fragment showing the date 1646 was recovered from the shoreline of St. Mary’s City, Maryland. Fortunately, this comparable example is large enough to ascertain that the vessel had alternating rampant lions; the armorial crest was attributed to an unidentified Roman Catholic cardinal.[6] Similar vessels not only appear in Dutch genre paintings of the period but also are found at sites in the New World with links to the Dutch trade.[7]

Earthenware

The cellar deposit also contained vessel fragments representing several types of earthenware, including Border ware, lead-glazed earthenware, North Devon sgraffito and gravel-tempered wares, and green-glazed floor tiles. While it is impossible to determine vessel form from the small sherds of yellow-glazed Border ware, pierced fragments from another vessel made of lead-glazed earthenware suggest it once functioned as a colander or bowl typically used for drying fruit or vegetables (fig. 7). This type of vessel is commonly depicted in seventeenth-century Dutch genre paintings (fig. 8).

Careful mending of other redware fragments with a manganese lead glaze helped to identify a bulbous, handled cup form (fig. 9). The cup is surprisingly thin-walled and delicate for what is generally considered a utilitarian ware.

The assemblage also included sherds from two unidentified North Devon sgraffito vessels but only one example of North Devon gravel-tempered earthenware, evidenced by the partially mended rim of a milk pan with a diameter of seventeen inches. The low number of gravel-tempered vessels found is particularly unusual for a Providence settlement site, suggesting the assemblage reflects a relatively high-status household.

The ceramic assemblage from Feature 30 is also notably distinct from other Providence settlement sites that have been subjected to vessel analysis (fig. 10), and from this arise two main points. The first, already noted, is the low percentage of ceramic products from North Devon, England. In most other Providence sites the average is greater than 40 percent—and in some contexts significantly more than that. The second important point is that tin-glazed earthenware makes up fully half of the twenty-eight vessels recovered from Feature 30, the highest amount yet seen from a Providence context. Archaeologist Paul Huey notes that a similarly high percentage of delftware is an attribute often seen in archaeological assemblages from a number of seventeenth-century Dutch colonial sites in New York, notably Fort Orange.[8]

Tin-glazed Earthenware

As previously noted, the cellar contained a highly unusual assortment of decorated and undecorated delftware design motifs and forms. A white-glazed delftware candlestick is perhaps the most extraordinary find, being only the second example recovered by the Lost Towns Project in more than a decade of archaeological excavations at nearly twenty seventeenth-century sites (fig. 11).[9] The candlestick’s mid-drip pan and trumpet base are undoubtedly modeled after a mid-seventeenth-century metal prototype (fig. 12).

A similar candlestick in the possession of the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, which is dated 1648 and bears the arms of the Fishmongers’ Company, is purported to be the earliest known dated candlestick (fig. 13). Michael Archer has noted that candlesticks from later in the seventeenth century have a simpler, straight form, which suggests that the more elaborate molded form from Homewood’s Lot is closer to midcentury, as would be expected.[10]

Candlesticks of all types, including those made of delftware and more costly brass and silver, were considered a luxury in the New World during the mid-seventeenth century. Their relative scarcity is often tied to the expense associated with the manufacture of candles.[11]

The Homewood ceramic assemblage also included fragments of no fewer than three seemingly identical white-glazed delftware bowls, referred to as porringers and sometimes “bleeding bowls,” with rim diameters of 5 inches (fig. 14). Porringers probably served many uses in seventeenth-century households, and their presence here (as well as a pewter example found in a nearby plow-zone context) makes it likely that they were commonly used for the consumption of food. The surviving handle of one example displays an elaborate scroll pattern with two heart-shaped holes accompanied by a third round hole. Extant delftware porringers with similar handles, albeit decorated and dated, are illustrated in Dated English Delftware by Louis Lipski and Michael Archer. The two vessels with the closest handles have the unfortunately broad temporal range of 1650–1730, although the latter lacks the vertical sides seen in the earlier Homewood specimens.[12]

In addition to the candlestick and porringers, partially mended rims of two undecorated white-glazed plates were also recovered from Feature 30. These vessels had rim diameters of 8 1/2 inches. It has been suggested that the appearance of such plain white-glazed delftware in the mid-seventeenth century is tied to mass production or even the stylistic sensibilities of the Puritan reign.[13] It has also been noted that the plain white glaze on this type of ware “focuses attention on the form itself.”[14] Notwithstanding these theories and observations, it seems reasonable to assume that the manufacture of plain wares achieved a cost savings, as decorating by hand always involved another labor-intensive step in production during this period.

The Homewood deposit also included fragments of two delftware plates and a small bowl decorated with distinctive floral patterns not seen in specialized literature devoted to either English or Dutch delftware of the seventeenth century.[15] As with the plain white examples, these plates had diameters of 8 1/2 inches. The first plate fragment displays a central motif involving an ovoid flower vase (fig. 15). This type of design is seen on two plates excavated in Norwich, England, which are illustrated in Eighteen Centuries of Pottery from Norwich (fig. 16).[16] One of the two examples (number 1375) is an almost identical match; excavated from a spoil dump on London Street, it is attributed as “probably Dutch, 1640–60.”

The second plate fragment from Feature 30 displays a floral border that is very similar to the design seen on a late-seventeenth-century Dutch plate, also found in Norwich, and attributed to Dutch manufacture (fig. 17).[17]

Finally, it has proved to be even more difficult to find any stylistic analogies for the fragment of a small bowl or teacup with a footring diameter of 2 1/2" (fig. 18). Although completely different in execution and body, a Portuguese plate from the early seventeenth century is the closest comparable design motif discovered in the literature.[18] While the Feature 30 vessel might seem more in line with English teacups from later periods, its 1660s discard date is indisputable, coming as it did from the lower levels of the intact cellar feature.

Conclusions

Homewood’s Building A, the oldest of eight structures known to have existed on the property, was an unusually small, heated building. Similarly, the trash-filled storage feature beneath its floorboards was notably smaller than several others excavated at the Providence settlement. Despite this limited volume, Feature 30 proved to have an interesting and enlightening ceramic assemblage.

The tightly dated and unusual assortment of ceramics discovered in this deposit affords a fascinating glimpse of the range of different types of European wares accessible to a single household in the Chesapeake in the mid-seventeenth century. Particularly notable were the unusual composition of certain items—including low percentages of North Devon ware and utilitarian ceramics in general and a high percentage of tin-glazed earthenware, including a rare candlestick.

The high percentage of delftware has been seen in other New World contexts as an indication of Dutch influence. In fact, many types of artifacts from Holland are found at Providence sites, notably pipes and ceramics as well as basic construction materials such as pantiles, painted tiles, yellow brick, and green- and yellow-glazed floor tiles. The ceramics recovered from Feature 30 include some that are clearly Dutch in origin, some that are possibly Dutch, and some that are often portrayed as being components of Dutch trade.[19] These findings provide additional evidence of Dutch influence within the Chesapeake, at a mid-seventeenth-century Puritan settlement.[20]

Al Luckenbach, Providence 1649: The History and Archaeology of Anne Arundel County, Maryland’s First European Settlement (Annapolis: Maryland State Archives; Crownsville: Maryland Historical Trust, 1995).

Lauren Franz and Al Luckenbach, “The Building Sequence at Homewood’s Lot, Anne Arundel County, Maryland,” Maryland Archeology 40, no. 2 (2004): 19–28.

Ibid.

David A. Gadsby and Rosemarie Callage, “Homewood’s Lot through Four Generations,” in The Clay Tobacco-Pipe in Anne Arundel County, Maryland (1650–1730), edited by Al Luckenbach, C. Jane Cox, and John Kille (Annapolis, Md.: Anne Arundel County Trust for Preservation, 2002), p. 18. Because the diameters of pipe stems have been shown to change over time, a statistical analysis of their measurements is used to determine the dates of various archaeological sites. Formulas proposed by Lewis Binford and Lee Hanson were used in this analysis; Binford, “A New Method of Calculating Dates from Kaolin Pipe Stem Fragments,” Southeastern Archaeological Conference Newsletter 9, no. 1 (1962): 19–21; and Hanson, “Kaolin Pipestems—Boring In on a Fallacy,” Historical Site Archaeology 4 (1969): 2–15.

Al Luckenbach and James Gibb, “Dated Window Leads from Colonial Sites in Anne Arundel County, Maryland,” Maryland Archeology 30, no. 2 (1994): 23–28 (1999 Addendum). An analysis of lead window cames has indicated that they were seldom curated for long and that their dates generally correspond with some specificity to the assumed construction dates of the associated building. See also Al Luckenbach and Shawn Sharpe, “A Seriation Analysis of ‘Trade’ and ‘Belly Bowl’ Tobacco Pipe Forms from ca. 1655 to ca. 1725,” Maryland Archeology 43, no. 2 (2007): 28–33.

Silas D. Hurry, Martin E. Sullivan, Timothy B. Riordan, and Henry M. Miller, “—once the metropolis of Maryland”: The History and Archaeology of Maryland’s First Capital (St. Mary’s City, Md.: Historic St. Mary’s City Commission, 2001), p. 46.

Richard G. Schaefer, A Typology of Seventeenth-Century Dutch Ceramics and Its Implications for American Historical Archaeology, BAR International Series 702 (Oxford, Eng.: J. and E. Hedges, 1998), p. 134; and Charlotte Wilcoxen, Dutch Trade and Ceramics in America in the Seventeenth Century (Albany, N.Y.: Albany Institute of History and Art, 1987), p. 73.

Schaefer, A Typology of Seventeenth-Century Dutch Ceramics, p. 102.

In March 2007 the Lost Towns Project recovered a portion of a yellow-glazed Border ware candlestick from the home site of the Samuel Chew family at Fairhaven, Maryland. Samuel Chew Sr. was an original lot holder in the Town of Herrington (ca. 1660s).

Michael Archer, Delftware: The Tin-Glazed Earthenware of the British Isles (London: The Stationery Office, in association with the Victoria and Albert Museum, 1997), p. 327.

Louis L. Lipski and Michael Archer, Dated English Delftware: Tin-glazed Earthenware, 1600–1800 (London: Sotheby Publications, 1984), p. 152.

Ibid., nos. 1230 (1650), 1237 (1698), 1240 (1727), and 1241 (1730).

Maryland Archaeological Conservation Laboratory’s “Diagnostic Artifacts in Maryland,” available online at the website of the Jefferson Patterson Park and Museum, www.jefpat.org/diagnostic/Historic_Ceramic_Web_Page/Historic%20Ware%20Descriptions/tin_glazed.htm (accessed December 7, 2010).

Amanda E. Lange, Delftware at Historic Deerfield, 1600–1800 (Deerfield, Mass.: Historic Deerfield, Inc., 2001), p. 90.

This survey included John C. Austin, British Delft at Williamsburg (Williamsburg, Va.: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, in association with Jonathan Horne Publications, 1994); Frank Britton, London Delftware (London: J. Horne, 1987); Dingeman Korf, Nederlands Majolica (Haarlem: DeHaan, 1981); Lange, Delftware at Historic Deerfield; Lipski and Archer, Dated English Delftware; Anthony Ray, English Delftware Pottery in the Robert Hall Warren Collection, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford (Boston: Boston Book & Art Shop, 1968); and Jan Daniël van Dam, Delffse Porceleyne: Dutch Delftware, 1620–1850 (Amsterdam: Rijksmuseum, 2004).

Sarah Jennings, Eighteen Centuries of Pottery from Norwich, East Anglian Archaeology Report No. 13 (Norwich, Eng.: Norwich Survey in collaboration with Norfolk Museums Service, 1981), pp. 189, 191, fig. 83, nos. 1375, 1376.

Ibid., pp. 192–93, fig. 84, no. 1379.

Rafael Salinas Calado and Jan Baart, Portuguese Faience 1660–1660 (Lisbon: Secretary of State for Culture; Amsterdam: Amsterdam Historical Museum, 1987), p. 29.

See Wilcoxen, Dutch Trade and Ceramics in America, p. 79.

Luckenbach, Providence 1649; C. Jane Cox and Al Luckenbach, “The Dutch Connection: ‘Providence’ within the 17th Century Chesapeake,” presented at the Society for Historical Archaeology Annual Conference, Jamestown, Virginia, 2007.