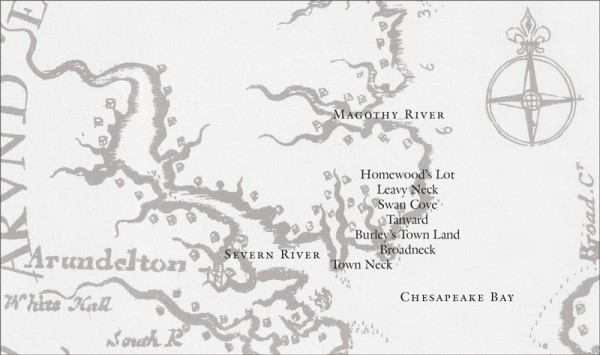

Providence settlement sites overlaid onto detail of Virginia and Maryland, map drawn by Augustine Herrmann in 1670 and published in 1673. (Private collection.)

Lost Towns Project archaeologists and volunteers conducting salvage excavations at Homewood’s Lot, 2002. (Photo, Shawn Sharpe, Lost Towns Project.)

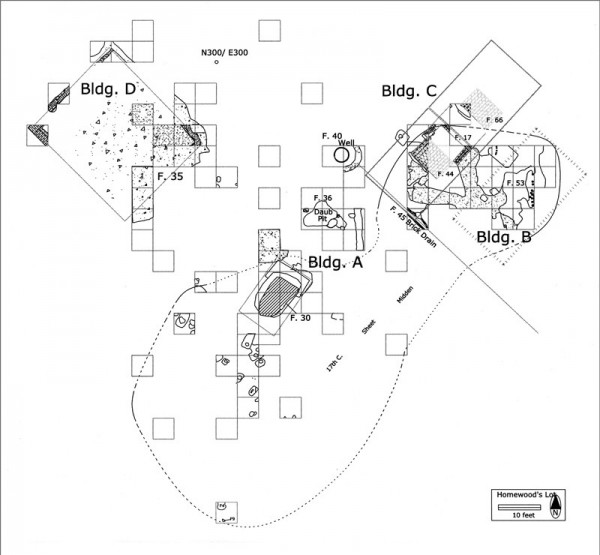

Archaeological plan view map of Homewood’s Lot, 2004. (Courtesy, Lost Towns Project.)

Archaeological profile of the cellar designated as Feature 30, Homewood’s Lot, 2002. (Photo, Al Luckenbach.)

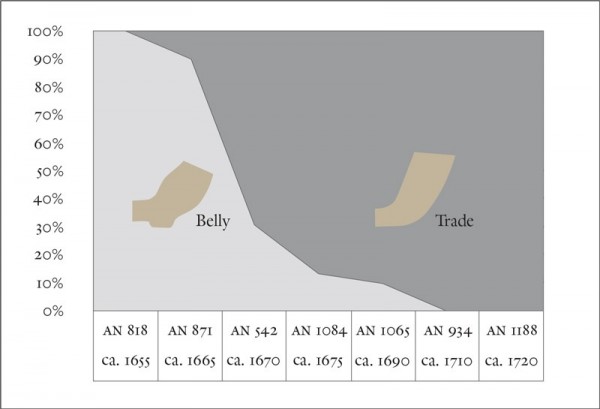

Chart comparing temporal ranges and percentages of belly bowl and trade pipe forms recovered from archaeological sites in Anne Arundel County, Maryland, including Homewood’s Lot (18AN871).

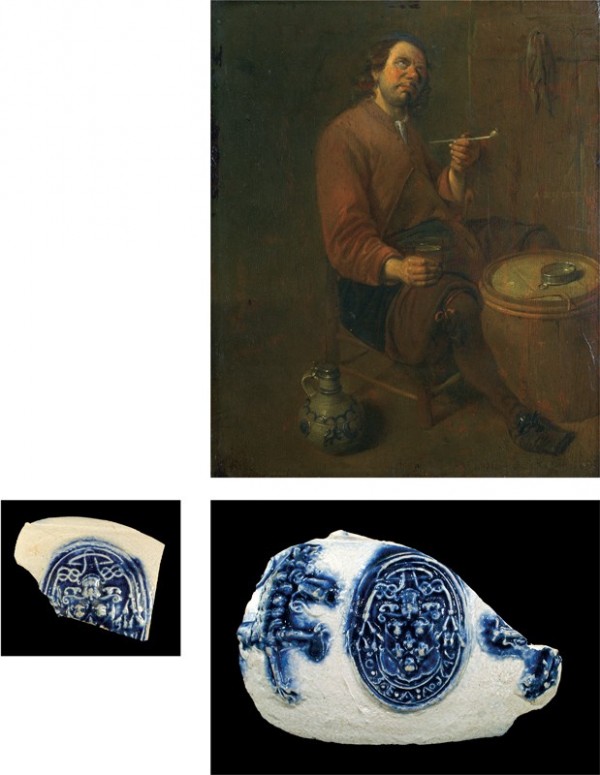

Arent(?) Diepraem, A Peasant Seated Smoking, ca. 1650. Oil on oak. 11 1/4" x 9". (Courtesy, The National Gallery, London.) The decorative elements on a Rhenish jug seen in the foreground of this painting bear a remarkable similarity to the fragments below, which were recovered from the shoreline of St. Mary’s City, Maryland (right), and Feature 30, Homewood’s Lot (left). A date of 1646 is visible (at approximately 4:00) on the medallion found at St. Mary’s City. (Courtesy, Historic St. Mary’s City.)

Detail of fragments of a colander similar to the one illustrated in fig. 8. The lead-glazed earthenware fragments are possibly Holland, ca. 1660s.

Nicholas Maes, A Girl Plucking a Duck, 1634. Oil on canvas. 23 5/8" x 26". (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art.) The colander depicted in this painting provides a suitable comparison for an overlay of several fragments from a similar vessel recovered from Feature 30, Homewood’s Lot.

Handled cup fragments, England, ca. 1660. Manganese-enriched lead-glazed earthenware. (Photo, John E. Kille.)

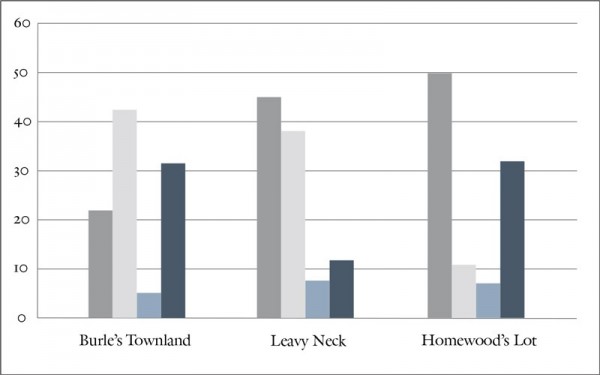

Chart comparing ceramic assemblages recovered from Burle’s Townland, Leavy Neck, and Homewood’s Lot sites, Providence, Maryland.

Mid-drip candlestick fragment, probably England, 1660s. Tin-glazed earthenware. (Photo, John E. Kille.)

Jan van der Heyden (1637–1712), Still Life with Books and a Globe, seventeenth century, Southern Netherlands (modern Belgium). Oil on panel. 8 15/16" x 10 5/8". (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art.) This painting includes a candlestick typical of the seventeenth century.

Candlestick, Southwark, probably Pickleherring, London, 1648. Tin-glazed earthenware. H. 10 3/16". (Courtesy, Victoria and Albert Museum.) This rare example is decorated with the arms of the Fishmongers’ Company and is inscribed “W / W / E / 1648.”

Handle and porringer fragments, probably England, ca. 1660s. Tin-glazed earthenware. D. of rim 5". (Photo, John E. Kille.)

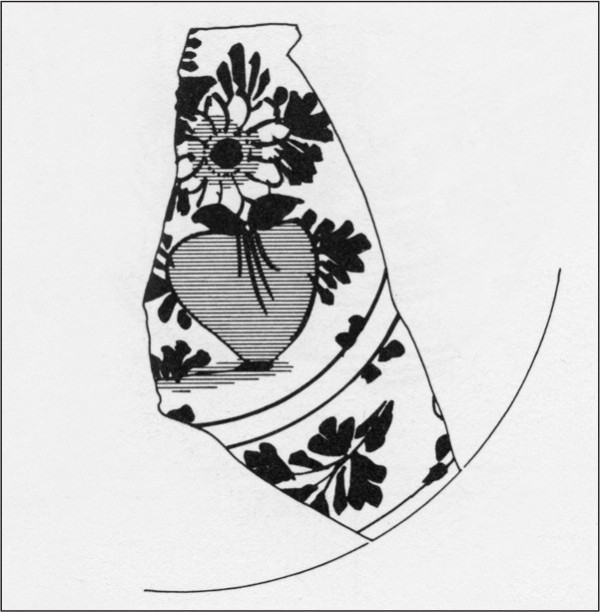

Plate fragments, the Netherlands, ca. 1660s. Tin-glazed earthenware. D. 8 1/2". (Photo, John E. Kille.)

Drawing of a 17th-century tin-glazed earthenware plate attributed to Holland manufacture, illustrated in Sarah Jennings, Eighteen Centuries of Pottery from Norwich, East Anglian Archaeology Report No. 13 (Norwich, Eng.: Norwich Survey in collaboration with Norfolk Museums Service, 1981), p. 191.

Plate fragment, the Netherlands, ca. 1660s. Tin-glazed earthenware. (Photo, John E. Kille.) The extrapolated diameter of the plate is 8 1/2".

Bowl fragment, probably England, ca. 1660s. Tin-glazed earthenware. (Photo, John E. Kille.) The extrapolated diameter of the footring is 2 1/2".