Jar, Paul Cushman, Albany, New York, 1805–1833. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 14 1/8". Stamp: PAUL:CUSHMANs / STONE•WARE•FACTORY (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Paul Cushman, 2002.)

The author with a selection of Cushman stoneware. Photo, ca. 1980.

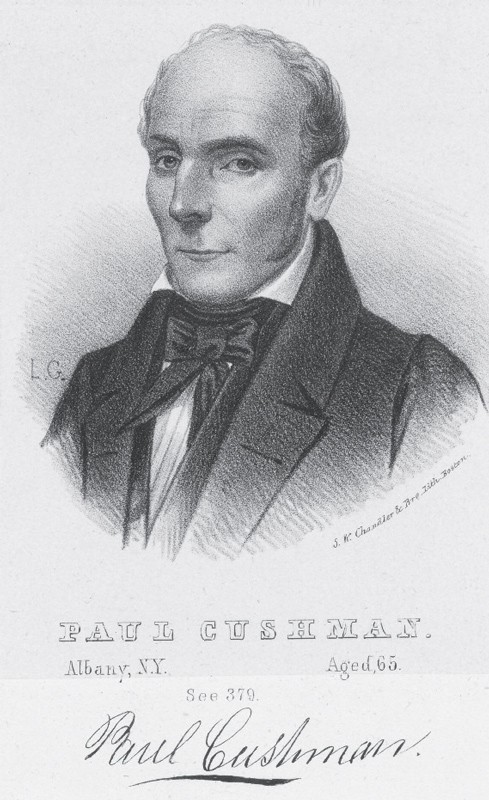

Paul Cushman. Engraving. From Henry Wyles Cushman, A Historical and Biographical Genealogy of the Cushmans: The Descendants of Robert Cushman, the Puritan, from the Year 1617 to 1855 (Boston: Little, Brown, 1855).

James Eights, “STATE and PEARL STREETS, ALBANY. 1806.” Colored engraving. After a circa 1850 watercolor.

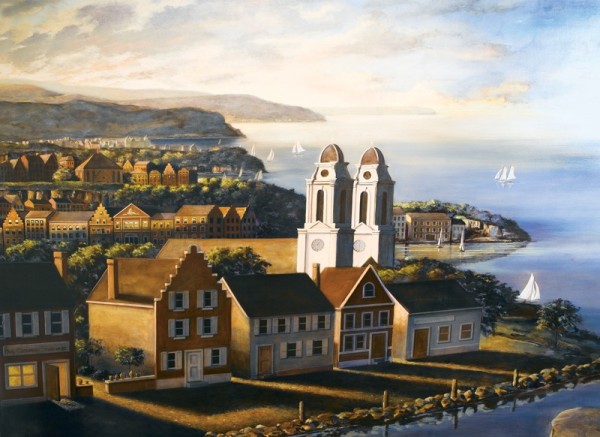

Mark Reynolds, Diorama of the Albany waterfront painted on the wall in the hallway of the author’s Manhattan apartment, 2004.

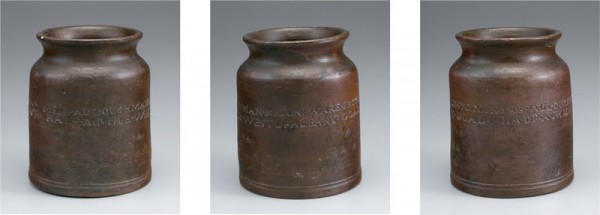

Jar, Paul Cushman, Albany, New York, 1809. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 7". Impressed mark: 1809 PAUL•CUSHMAN’s• STONE•WARE FACTORY• / HALF • A MILE WEST OF ALBANYGOAL (Unless otherwise noted, all objects from the author’s collection; photos, Gavin Ashworth.)

Jar, Paul Cushman, Albany, New York, 1809. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 7 3/8". Impressed mark: 09PAUL•CUSHMAN•s•STONE•WARE•FACTORY1809PA

Jar, Paul Cushman, Albany, New York, ca. 1809. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 9 1/2". Impressed mark: PAUL•CUSHMAN STONE•WARE•FACTORY

Jar, Paul Cushman, Albany, New York, ca. 1809. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 7 1/2". Impressed: PAUL:CUSHMAN

Jar, Paul Cushman, Albany, New York, 1805–1833. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 7 3/8". Impressed mark: PAUL:CUSHMAN / STONE•WARE•FACTORY

Jar, Paul Cushman, Albany, New York, ca 1805–1833. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 8 1/2". Impressed mark: PAUL: CUSHMAN

Jar, Paul Cushman, Albany, New York, 1805–1833. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 9 1/4". Impressed mark: PAUL: CUSHMAN

Jugs, Paul Cushman, Albany, New York, 1805–1833. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. of the tallest 16 1/4". The jug on the left retains its label from the George McKearen Collection.

Jugs, Paul Cushman, Albany, New York, 1805–1833. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. of the tallest 15".

Crock, Paul Cushman, Albany, New York, 1805–1833. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 7 1/4". Impressed: PAUL:CUSHMANS

Jar, Paul Cushman, Albany, New York, 1805–1833 Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 7 1/2". Impressed: PAUL:CUSHMAN

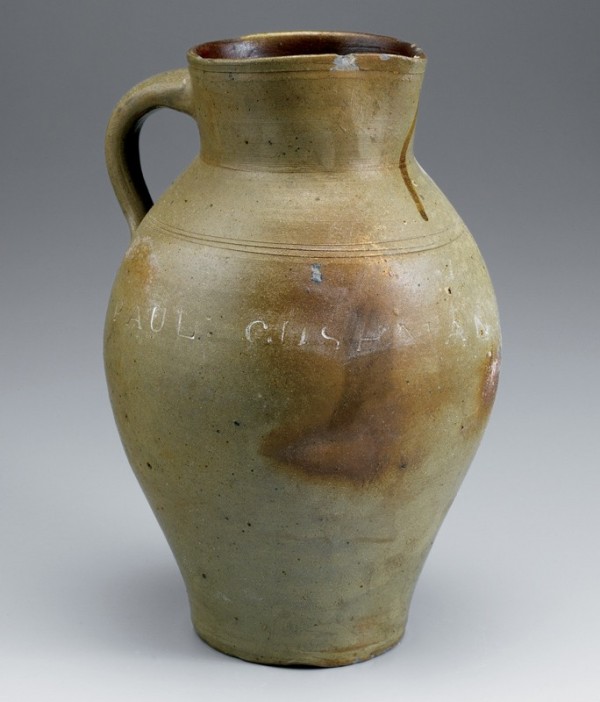

Pitcher, Paul Cushman, Albany, New York, 1805–1833. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 12". Impressed: PAUL:CUSHMAN

Cooler, Paul Cushman, Albany, New York, 1818. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 23 1/2". (Albany Institute of History & Art, bequest of James Ten Eyck.)

Jar, Paul Cushman, Albany, New York, 1809. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 10". Rouletted marks: PAUL• CUSHMAN’s:STONE•WARE• FACTORY•1809 / HALF•A•MILE•WEST OF ALBANY•GOAL•. Incised inscription: A C Russell / Pott / Sunday. (Private collection.)

Views of the mouth (left) and base (right) of the jar illustrated in fig. 19.

Photograph of Paul Cushman the Second (1822–1895), ca. 1870.

Jug, probably New York, ca. 1870. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 8 3/4". Inscribed in cobalt blue: P. Cushman Co. / Wines Brandies &c. / 367 & 378 Broadway / Albany / NY

Photograph of Harry Curtis Cushman (1857–1918), ca. 1910.

Portrait of the author, ca. 2007, holding a jug made by his great-grandfather.

Stoneware made by Paul Cushman (1767–1832) of Albany, New York, securely dated to the first quarter of the nineteenth century, is remarkably distinctive and is eagerly sought by collectors.[1] His pieces frequently display interesting or noteworthy eccentricities and have, nearly two hundred years later, transcended the merely utilitarian to assume a special place in American decorative arts (fig. 1).

Paul Cushman was my great-grandfather, and many of his pieces found a permanent home in our family (fig. 2). We saw these creations as a very special part of our remote Albany past. My father, Paul Cushman (the third to bear the name), had inherited a few from his forebears and added others to his collection. However, since we lived in a splendid Manhattan duplex apartment that my mother had furnished with many high-style antiques and impressionist paintings, the Cushman pots were tolerated as extraordinary and special in their way but not sufficiently decorative for the living room. Accordingly, they were relegated to lesser places—the library shelves or in closets. It has been my pleasure to see the Cushman pieces given a more rightful place up front.

With considerable diligence over the course of many years, I had traced well over two hundred pieces of marked Cushman pieces, including pots, jars, crocks, coolers, a chamber pot, and a milk pail. Many of these remain with our family; some are in the Albany Institute of History and Art (AIHA); some are in the hands of Warren Hartmann, a serious collector; others are in museums with early American pottery collections.

Paul Cushman the potter had a kindly gentle mien (fig. 3). In Henry Wyles Cushman’s 1855 genealogy of the family, Paul is described by his second son, William McClelland Cushman, as tall, enterprising, and “ingenuous”: “Possessed with a hardy constitution, sagacious but not highly cultivated . . . methodical and circumspect and retaining the high morals of his youth.”[2]

Paul came from a long line of New England ancestors, most of whom were farmers, among them Paul’s father, Seth. As a teenager Paul showed his patriotic spirit by volunteering for service in the Revolutionary Army. By the start of the nineteenth century, he had settled permanently in Albany and in 1803 married Margaret MacDonald. Initially he was deeply involved in development along the expanding Albany waterfront, as the city was capitalizing on the growing commercial importance of the Hudson River (figs. 4, 5). But the City of Albany abruptly ended his successful business by expropriating all of his improvements in 1806 in order to make way for an important new public market. He faced the need for a steady income to feed and sustain his family, which now included an infant son.

In 1806 Paul Cushman bought lots on the outskirts of the city and began to make stoneware. There is no data suggesting he had prior experiences in pottery, a demanding and difficult craft, although he might have learned the business on the job. His likely mentor was William Capron, a recognized Albany predecessor in stoneware, or one of his employees. At any rate, Paul settled into the combined home and pottery site, where he potted until 1833.

No physical trace of the pottery building survives, nor any of his tools, cog wheels, or stamps. There are no illustrations of his workshop or related piles of wood, clay, or detritus to show us exactly what the operations looked like. All that remains are his stoneware and a few related business documents such as tax records and orders.

Fortunately, many of the pots that survive give us information about the location of Cushman’s pottery (fig. 6). His most distinctive and interesting mark is “1809 PAUL•CUSHMAN’S• STONE•WARE FACTORY• / HALF • A MILE WEST OF ALBANYGOAL” The primary mark is PAUL CUSHMAN, occasionally with a small “S’” after Cushman. The height of the letters is usually 1/4" or 1/2"; some are 7/16". Between PAUL and CUSHMAN (closer to PAUL) is a pair of dots, slanting to the right at about a 30-degree angle. There are slight variations in the placement of the two dots; occasionally they are vertically aligned. It is possible they served as reference marks for aligning the separate “PAUL” and “CUSHMAN” stamps.

Sometimes Cushman’s name is followed by STONEWARE•FACTORY, with the dot placed centrally between the words. Rarely, two stamped dates (1809 and 1811) were added to the marks. The jar illustrated in figure 7 shows the mark 09PAUL•CUSHMAN•s•STONE•WARE•FACTORY1809PA. The “09” at the front reflects a mistake on the part of the potter, who misapplied the lettering on the coggle wheel. Presumably, this should be PAUL•CUSHMAN•s•STONE•WARE•FACTORY1809.

On some pieces, STONEWARE•FACTORY is followed by HALF•A•MILE WEST•OF ALBANY•GOAL. The term goal might seem to be a misspelling of gaol, a chiefly British term for jail, but it is spelled that way in several documents from the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, including the proceedings of the New York State Assembly.

Today the site is a small, paved, triangular-shaped plot, where Washington Avenue bifurcates into highways leading west and north. As potteries usually are considered undesirable neighbors owing to their piles of lumber, barrels of clay, intense smoke when the kiln is being fired, foul water, and sherds, it was well that he set up his home and business one-half mile from the jail, which at that time was some distance from Albany proper. In 1811 the jail was moved closer to town, which might explain why Cushman’s later date stamps do not refer to the distance from it.

In the age of horse-and-buggy travel, the Cushman mark, label, and stamp were an early means of advertising and helped market his goods in the Albany area. More distant sales usually required transporting via the ships moving up and down the Hudson River. Initially these ships were powered by sail, but after Robert Fulton’s success with his Clermont invention in 1807, they were soon eclipsed by steam-powered vessels. The actual marketing probably involved commercial distributors supplemented by some itinerant peddlers serving the interior sections. Cushman pieces have been unearthed throughout the Hudson and Mohawk valleys and places more distant; one piece is inscribed in cobalt script, “Cooperstown.”[3]

Cushman’s clay came from New Jersey. Early in the manufacture of New York City stoneware, the special clay capable of withstanding the intense heat came from a few limited deposits in and near Manhattan. But it was the abundance of very fine clay in the Amboy area of New Jersey that supplied Cushman’s needs, and we know how this part of the business was carried out. A letter of agreement from Cushman to Andrew K. Morehouse, a clay supplier, reveals the details of a barter arrangement. The quality clay used by the leading Manhattan and New Jersey potters went up the Hudson River by boat, was used by Cushman to make his products, and then a percentage of the fired pots was sent back by boat. Neither cash nor credit was involved: the clay supplier was recompensed from whatever he could realize from the sales of the products he received from Cushman.

Finished Cushman pieces generally retain the basic color of the original clay and range in appearance from homogeneous to streaked, blotchy, or even mottled. The surface glistens with the shiny, somewhat roughened exterior glaze. The interior is covered in the contrasting dark brown hue of an applied slip, usually referred to as Albany slip, the material for which would have been obtained from the nearby Hudson River. Firing it produced a handsome, relatively homogeneous dark chestnut color.

Occasionally a piece, usually a jar, received a coat of the same slip on the interior and exterior. Sometimes the exterior slip was not applied uniformly (figs. 8, 9), and the resultant hue is a cheery contrast to the usual colors of the basic clay—sandy, ocher, gray, and pale or dark brown—as found on the standard pieces.

The cobalt oxide, which had to be purchased from a supplier, was used somewhat sparingly by Cushman. After firing, the applied cobalt turned a characteristic blue color, which contrasts nicely with the basic gray of the fired clay. Typically, cobalt was brushed (usually somewhat thinly) over marks or around the attachment of the handle bases to the main body, as a highlight (figs. 10-12). As with other stoneware makers, Cushman created incised and rouletted surface decorations using a combination of geometric and floral designs.

We are fortunate that an 1830 receipt for a stoneware load survived in our family and is now in the Albany Institute.[5] The receipt documents a specific kiln firing and lists the vessel forms Cushman produced: jugs, crocks, pots, jars, and pitchers (figs. 13-17). Containers were sold according to their volume sizes—pint, quart, one gallon, two gallon—and usually either in single units or by the dozen. Water coolers, bottles, churns, milk pails, and possibly an inkwell were also shipped on occasion. The prices quoted were very modest: just a few pence (America was slow to replace English currency).

The proceeds from stoneware manufacture must have been sufficient to support Paul and his family, although the business could not have been particularly lucrative as the firings were infrequent—estimated about every few months—and the prices low. On two occasions Cushman found himself the loser in court for nonpayment of charges: a court judgment against him in 1817 for $1,000 was followed seven years later by the Supreme Court ruling against him for a $600 debt. Another indication of monetary problems is evident in an advertisement he placed in the Albany Daily Advertiser on September 28, 1828, offering his redware and stoneware business for sale.

Several Cushman pieces have irregularities in their shapes and surfaces, presumed to be unintentional defects. Some pieces are asymmetrical, even misshapen. Others came out of the kiln with firing defects, such as an extrusion in a bit of the wall. Still others sagged during firing, leaving a distorted form.

Cushman created stoneware in a highly individualistic way. His most eccentric artistry showed in his painted cobalt embellishments, probably because he was not a particularly good or careful artist. At times the cobalt wash extends beyond the name and seems hastily painted; sometimes it dribbled down. In eighteen of the known surviving pieces, some sort of form resembling branching plants was painted in with cobalt but differs both in shape and in the thickness of the cobalt.

To explain such irregularities and carelessness, some have questioned Paul Cushman’s sobriety. Although the Paul Cushman entry in the 1855 genealogy states, “Never at any period, was he obnoxious to the charge of the besetting sin of his age—intemperance,” concealment of alcohol problems, even from family genealogy writers, is not unknown. I prefer the term exuberance to account for the relatively sloppy but ambitious application of decoration.

Occasionally, the Cushman pottery produced special objects decorated specifically as commemorative or presentation pieces. The Albany Institute of History & Art has a first-rate example of a cooler heavily ornamented with, among other designs, a heart, initials, a flag, and an 1818 date (fig. 18).

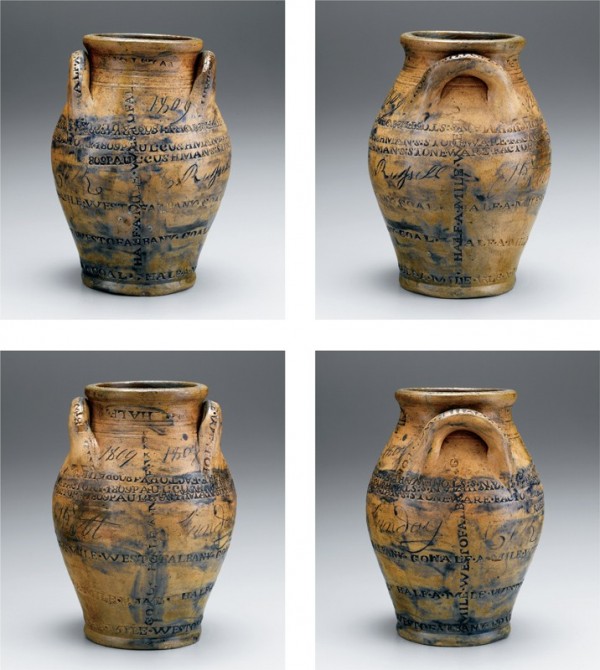

Another jar was obsessively decorated with Paul Cushman’s signature roulette, “PAUL•CUSHMAN’S:STONE•WARE•FACTORY•1809 / HALF• A•MILE•WEST OF ALBANY•GOAL•,” in crisscrossed, vertical, and horizontal fashion over the entire piece, including handles, rim, and unglazed bottom (figs. 19, 20). The inscribed “A C Russell” is probably the intended recipient of this extraordinarily individualized piece.

In the early 1800s settlers traveled north from New York City up the Hudson River and west along the Mohawk Valley, spreading out from the rivers. Most federal kitchens or farms happily used stoneware for everyday use, and Cushman found a ready market for his pieces, enhanced by his geographically fortunate pottery location: in Albany, on the Hudson, and near the sources of raw materials. He was optimally sited to supply stoneware to the residents in the Upper Hudson, Albany, and the Mohawk Valley west. There were some Albany stoneware competitors, among them Joshua Boynton, who in 1818 advertised his stoneware shop located across the street from the Cushman pottery. Cushman withstood the rivalry, however, and Boynton soon moved away.

However well he may have dominated the local stoneware market, however, Cushman was buffeted by the changing times. The opening of the Erie Canal in 1824 allowed for much greater business with the west. Potters proceeded to set up kilns farther into the hinterland, and Paul lost much of his competitive advantage. My father used to say—and Cushman’s son agreed with him—that the Erie Canal put our potter ancestor out of business, but this is at least somewhat exaggerated, as the kiln actually continued in operation for another eight years, until Margaret Cushman sold it in 1833 after her husband’s death.

It is hardly surprising that the occasional new Cushman piece entering the market has usually come out of an old barn or farmhouse in the Hudson area. When my father was actively collecting in the 1940s and 1950s (within the limits established by mother), an occasional piece turned up in roadside barn sales. Sporadically, we would interrupt our motoring in the Hudson Valley to have a quick look. Rarely were these ventures successful. Father did have a principal supplier-dealer, glass expert George McKearen, who every once in a while would offer one for $25–$50. One of our jugs still retains the McKearen label. The prices to us were a hefty markup from the original, of course, but nowhere near the values today. Surely Paul and his scions would be proud to know how lasting his fame as a potter would be, and how desirable his works. We don’t know whether any of his helpers were involved in the decoration of Cushman pieces, but its relative consistency over the years suggests that Paul was the principal decorator.

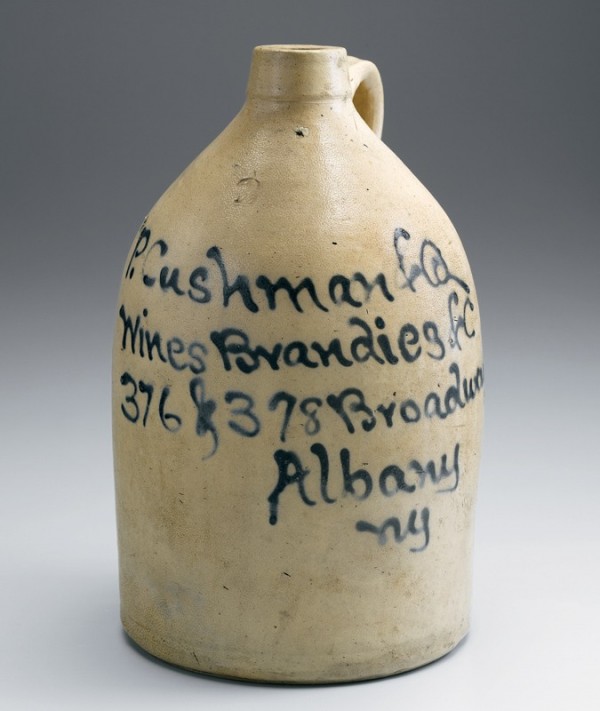

After Paul Cushman’s death in 1833, his widow failed to keep up the business, which was sold in that year. However, two of his sons, R. S. and Paul the Second, started up a wines and spirits business in Albany (fig. 21). They advertised their business using commercially obtained stoneware on which was painted in cobalt script their masthead and address (fig. 22). The business was taken over by Paul’s son, Harry Curtis Cushman (my grandfather), and prospered for more than fifty years (fig. 23). Significantly, they found that the way to make their fortune was not by selling empty containers—stoneware containers were so durable they represented a one-time sale, more often than not—but by selling the contents as well. These descendants made a tidy fortune, in contrast to the struggling potter.

Ultimately, however, potter Paul Cushman’s legacy was an important American ceramic one, as many of his pots have extraordinary, even unique, characteristics (fig. 24). Their imperfections and quirkiness add to their appeal as historical decorative art objects, particularly the charming label “HALF•A•MILE•WEST OF ALBANY•GOAL•.” Nowhere else in the field of American decorative arts is there a mark as entertaining as that of my great-grandfather.

This article is adapted from Paul Cushman Jr., “Paul Cushman: Albany’s Extraordinary Potter of Stoneware,” in Leigh Keno and Leslie Keno et al., Paul Cushman: The Work and World of an Early 19th Century Albany Potter, exh. cat. (Albany, N.Y.: Albany Institute of History and Art, 2007).

Henry Wyles Cushman, A Historical and Biographical Genealogy of the Cushmans: The Descendants of Robert Cushman, the Puritan, from the Year 1617 to 1855 (Boston: Little, Brown, 1855), pp. 204–7.

For an illustration of this pot, see Keno and Keno et al., Paul Cushman, p. 118, fig. 41.

Paul Cushman to Andrew K. Morehouse, Albany, September 1, 1829, Collection of the Albany Institute of History & Art Library, MG 52.

Packing list in letter from Paul Cushman to Andrew K. Moorehouse, Albany, August 25, 1830, Albany Institute of History & Art Library, MG 52.