Apothecary jar, Aldgate or Low Countries, 1607–1610. Delftware. H. 7 1/4". (Courtesy, Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Decorated with a stylized peacock feather motif. The jar was excavated by Jamestown Rediscovery,™ a project of the Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities (APVA) at the site of James Fort (1607), the earliest permanent English settlement in the New World.

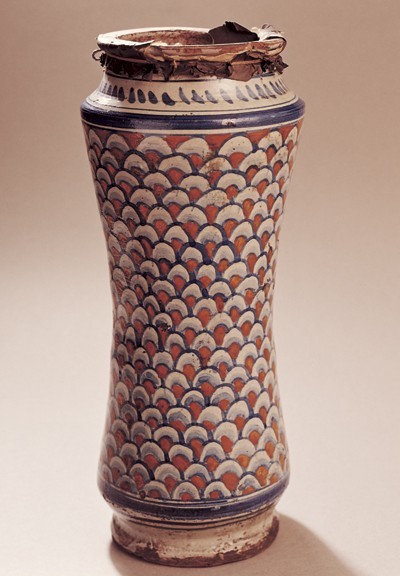

Albarello, Deruta, Italy, first quarter sixteenth century. Majolica. H. 12 1/2". (Courtesy, Germanischen Nationalmuseum, Nuremberg.)

Peacock feathers have provided decorative inspiration for centuries. The oldest known ornamental bird, the peacock figures largely in many cultures as a symbol of paradise or immortality. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

A tall cylindrical apothecary jar was recently recovered from a circa 1610 trash pit associated with the early English settlement at Jamestown, Virginia (fig. 1).[1] At first glance, it is difficult to see any relationship with the striking plumage of a peacock in its decoration. After all, aside from two manganese bands encircling the vessel, the palette is a monochromatic blue. Even the background tin glaze, which would normally provide a contrast in white, has a bluish cast, and the midgirth design—appearing like “scales with blobby dots,” or maybe even fish eggs—is hardly representative of peacock feathers. Or is it? Perhaps examination of a decorative antecedent to the Jamestown jar, dating a century earlier, will make the association clearer.

A tin-glazed earthenware jar, in the National Museum of Nuremberg, is painted with overall scale-work similar to the Jamestown jar, although its palette is a very colorful orange-brown and blue (fig. 2). A product of Deruta, Italy, the vessel is known as an albarello, from the twelfth-century Islamic wares used to hold medicines, spices, scents, herbs, and other precious substances on pharmacy shelves. The tall slender albarello form is thought to have developed from sections of bamboo stalks, which served as the traditional Arabic container for medicines.[2] The cylindrical shape was also practical as it enabled the vessels to stand close together on apothecary shelves, and the constricted mid-section provided an easy handhold for handling the jars.[3]

The Jamestown apothecary jar has lost its “waist” and reects the form’s more rounded transfiguration as it was transmitted from Italy to the Low Countries and Britain in the sixteenth century. In these countries, the form came to be known as the gallipot, which either refers to galleys—the at single-decked ships that traded Spanish and Italian tin-glazed earthenwares to the North—or to a derivative of an old Flemish word glei, meaning “porcelain clay.”[4]

Apothecaries primarily used gallipots for the storage of ointments, drugs, and other medical preparations, but these vessels are also mentioned in sixteenth-century inventories and cookbooks as domestic storage containers for foodstuffs. Gallipots are particularly mentioned in conjunction with the storage of comfits (sugar-coated spices) and suckets (citrus peels and/or fruits conserved in syrup). This association probably developed because comfits and suckets were part of the Arabic confectionery that was introduced to the western world—along with the colorful apothecary jars—as medicine. Sugars and other spices were considered to be good for the digestion, and this was the primary reason for serving them as part of a meal.[5]

The use of tin glazing on pottery, which produced an opaque white ground for colorful decoration, is believed to have developed in the Near East in the ninth century as an imitation of Chinese porcelain.[6] During the Middle Ages, the technique spread along trading networks through the Islamic countries, including southern Spain, and eventually to Italy. Deruta, located south of the Apennines near Perugia, became an important center for the production of tin-glazed earthenware, or majolica, at the end of the fifteenth century. During this early time period, patterns from Persian art as well as images on Chinese porcelain and designs borrowed from classical antiquity served as sources of decorative inspiration for the potters. The motif on the Deruta albarello is characteristic of Deruta wares during the first quarter of the sixteenth century and consists of a polychrome scale-work pattern, each scale with its central “eye.”[7] This device is derived from Islamic interpretations of the upper tail of the peacock, which is marked with iridescent ocelli (fig. 3).

The Jamestown apothecary jar, which dates to the beginning of the seventeenth century, is a very stylized interpretation of the peacock design. At present, it cannot be visually determined if the jar is an early London product, possibly Aldgate, or was made in the Low Countries. Attribution is especially complicated by the fact that the Aldgate pottery, which operated from 1571 to about 1615, was comprised of Flemish potters who had emigrated from Antwerp. Compositional analysis using neutron activation has proved quite helpful in sorting out the tin-glazed products of the two countries.[8] It is hoped that a continuation of the scientific analysis of these wares, coupled with further study of the physical attributes, will lead to more secure attributions in the future. For now, the Jamestown apothecary jar represents the transmission of centuries of culture that followed the hot winds of the spice route through Asia and the Middle East, bringing aromatic spices, succulent citrus fruits, and mystical medicines to Europe’s doors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The author thanks Ivor Noël Hume for pointing the way to Deruta.

Beverly A. Straube

Curator, Jamestown Rediscovery,™

Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities (APVA)

Jamestown, Virginia

<bly@apva.org>

Beverly Straube, “European Ceramics in the New World: The Jamestown Example,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2001), pp. 47–71.

David Harris Cohen and Catherine Hess, Looking at European Ceramics: A Guide to Technical Terms (Malibu, Calif.: J. Paul Getty Museum in association with British Museum Press, 1993), p. 27.

Bernard Rackham, Italian Maiolica (London: Faber and Faber, 1952), p. 13.

Frank Britton, London Delftware (London: Jonathon Horne, 1987), p. 22.

C. Anne Wilson, “The Evolution of the Banquet Course: Some Medicinal, Culinary and Social Aspects,” in ‘Banquetting Stuffe,’ edited by C. Anne Wilson (Edinburg: Edinburg University Press, 1991), pp. 9–35.

Rackham, Italian Maiolica, p. 2.

Silvia Glaser, Majolika (Nuremberg: Germanisches Nationalmuseum, 2000), p. 200.

Michael Hughes and David Gaimster, “Neutron Activation Analyses of Maiolica from London, Norwich, the Low Countries and Italy,” in Maiolica in the North: The Archaeology of Tin-Glazed Earthenware in North-West Europe c. 1500–1600, edited by David Gaimster. British Museum Occasional Paper Number 122 (London: British Museum, 1999), pp. 57–89.