Masonic table attributed to the shop of Henry Connelly, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1806–1810. Mahogany and satinwood with tulip poplar and white pine. H. 39", W. 49", D. 27". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum, bequest of Henry Francis du Pont; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Eagle, probably Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1810–1820. Pine. H. 24 3/4", W. 29 3/4", D. 28". (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art, gift of Thomas A. Andrews, 1889.) This object was attributed to William Rush by Henri Marceau and subsequently used by Robert Trump to attribute the eagles on the table illustrated in fig. 1 to Rush. Marceau’s attribution was refuted in 1982, in the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts exhibition catalogue William Rush, American Sculptor.

William Rush, Cherubim, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1820–1821. Unidentified wood. H. 48", W. 56". (Grand Lodge of Free and Accepted Masons of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Entry for March 1, 1820, in the Minutes of the Building Committee of the Grand Lodge of Free and Accepted Masons of Pennsylvania, 1819–1820. (Masonic Museum and Library of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia; photo, Gavin Ash- worth.) Rush received $90 for the completed work on May 25, 1821.

Detail of the left wing of the cherubim illustrated in fig. 3. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the left wing of the left eagle on the table illustrated in fig. 1. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

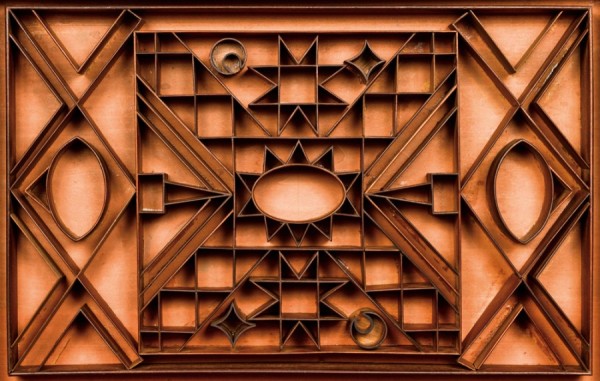

Detail showing the top center compartment of the table illustrated in fig. 1. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The center square is dominated by the saltire, or St. Andrew’s cross. A sun at the center of the cross is flanked by moons and stars. To the left and right of the sun are two niveaux, or French-style levels. Each niveau is composed of an A-frame holding a stone-block plumb bob. Each side of the compartment contains a square, compass, and vesica pisces.

Masonic apron, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1818. Satin-woven silk with silk, metallic, and chenille embroidery. 15 1/2" x 15 1/2". (Masonic Museum and Library of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia; photo, Dennis Buttleman.) This apron depicts the all-seeing eye, sun, moon, and stars.

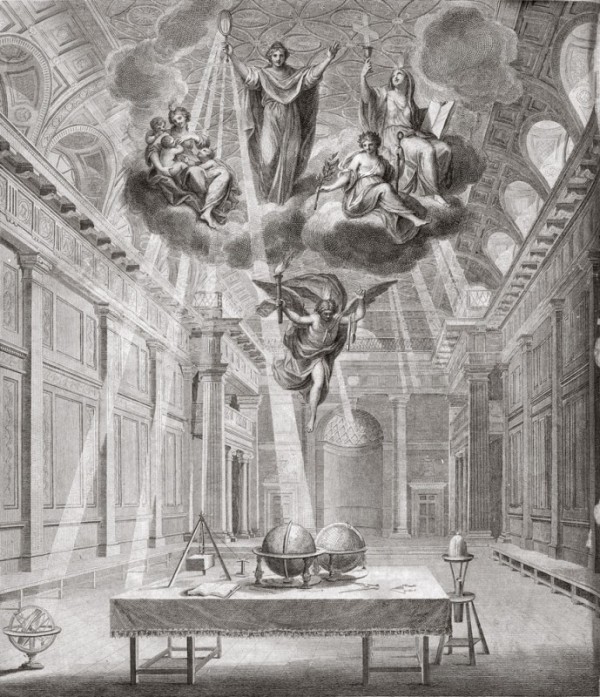

Frontispiece of The Constitutions of the Antient Fraternity of Free and Accepted Masons, 1784. (Courtesy, Scottish Rite Masonic Museum and Library, Van Gorden-Williams Library and Archives; photo, David Bohl.)

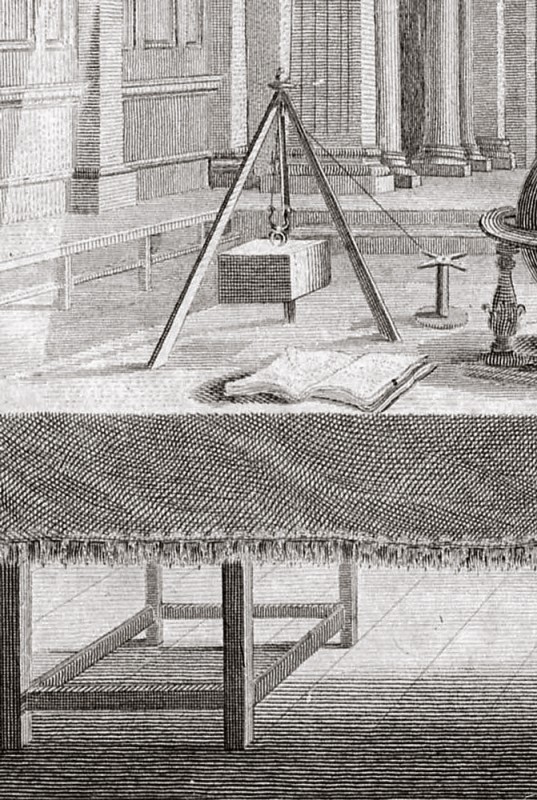

Detail of the frontispiece illustrated in fig. 9. The A-frame niveau with stone-block plumb bob is identical in design to that in the top center compartment (fig. 7) of the table illustrated in fig. 1.

M. Tyler & Co., water cooler, Albany, New York, 1825–1826. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Courtesy, Scottish Rite Masonic Museum and Library; photo, David Bohl.) The square and compass were the most commonly reproduced Masonic symbols in early American decorative arts.

Detail showing the bottom center compartment of the table illustrated in fig. 1. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The diagonal grid represents the black-and-white tiled floor—symbolizing good and evil—in King Solomon’s Temple. The compartment is an oblong, representing the floor plan of the temple and by extension the Masonic lodge. The three crowns stand for King Solomon, King Hiram of Tyre, and Hiram Abiff, the ill-fated architect of Solomon’s temple.

Detail of the apron illustrated in fig. 8 showing three crowns over the temple floor.

Detail showing the side compartments of the table illustrated in fig. 1. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) When the table’s two side compartments are pushed together, they form the royal arch keystone.

Mark medal, Bangor, Maine, 1849. Gold. (Courtesy, Scottish Rite Masonic Museum and Library, gift of Mr. and Mrs. Shattuck W. Osborne; photo, David Bohl.)

Detail of the top of the table illustrated in fig. 1. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Royal arch certificate attributed to engraver Charles Cushing Wright Homer, New York, ca. 1818. Line engraving on paper. (Courtesy, Scottish Rite Masonic Museum and Library, Van Gorden-Williams Library and Archives, Museum purchase; photo, David Bohl.) Royal arch certificates almost always show the ark of the covenant under the wings of two cherubim.

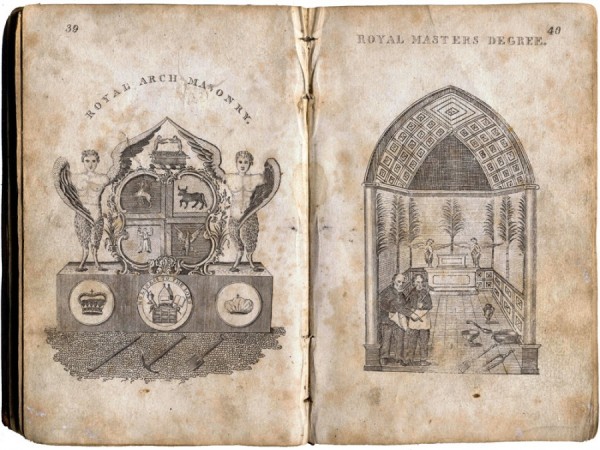

Amos Doolittle, Royal Arch Masonry, Royal Arch Degree, illustrated in pls. 39–40 in Jeremy Cross, The True Masonic Chart, or Hieroglyphic Monitor, 1819. Engravings. (Courtesy, Masonic Museum and Library of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia; photo, Dennis Buttleman.) Two cherubim protect the ark of the covenant with their outstretched wings in these popular royal arch engravings.

IN 1935 YORK, Pennsylvania, antique dealer Joe Kindig Jr. wrote to Wilmington, Delaware, collector Henry Francis du Pont, describing a recently acquired nineteenth-century pier table as “the best piece of its period” and the finest example of cabinetwork that he had encountered (fig. 1). Kindig added that the table “was probably made by the same man” responsible for a “fine satinwood kidney shaped sewing table” in du Pont’s collection and that Philadelphia cabinetmaker Henry Connelly was the prime candidate. Du Pont purchased the pier table two years later for use in his library.[1]

Du Pont was undoubtedly intrigued by the pier table’s design, which decorative arts scholar Charles Montgomery later described as “unique in the annals of furniture making in any country.” The front legs are decorated with carved eagles whose wings extend across the front and adjoining side rails. Each eagle rests on a square block that extends down into a Corinthian capital followed by a reeded pillar, a four-toed lion’s-paw foot, and another square block. To accommodate the eagles’ sculptural form and integration with the rails, the front legs project from under the case by approximately half their width.[2]

The construction of the table is as distinctive as its carved decoration. Its white pine top is veneered with fourteen satinwood rays emanating from a mahogany demilune, hinged to the solid mahogany rear rail, and recessed on the inside to accommodate a mirror, which is held in place with mahogany tenons and brass pins. The white pine front and side rails have curly satinwood veneer on their exterior surfaces and upper edges. The faces of the rails are decorated with rosewood banding and the edges with light and dark stringing. Front-to-rear mahogany boards divide the interior of the frame into three sections. The larger, center section holds two superimposed oblong trays, whereas the symmetrical flanking compartments hold one oddly shaped tray. Each tray is fitted with a silver ring-shaped lifting pull and divided into a complex array of small compartments by thin strips of mahogany.[3]

The design and construction of the table have complicated all previous attempts to categorize its function. In American Furniture: The Federal Period, 1785–1825, Montgomery argued that it should be “called a pier table only on the basis of height and general appearance.” The lack of veneer and other decorative details at the back suggests that the table was intended to sit against a wall; however, its hinged top, intricate interior, and zoomorphic form indicate functions different from those of a pier table. Montgomery believed the table was meant to house “curios, rough geological specimens, or, more probably, marbles or other stones cut to fit exactly into the small divisions.” In correspondence, he often referred to this object as a “shell table,” a logical assumption considering the popularity of natural history in eighteenth- and early-nineteenth-century Philadelphia. In deference to Montgomery’s theory, subsequent scholars adopted the term “collector’s table.”[4]

Montgomery was more ambivalent about the table’s attribution. Although he recognized that the veneer on the top resembled that on tables attributed to Henry Connelly, Montgomery proposed Joseph Barry as a possible maker. The table’s inclusion in antique dealer Robert Trump’s 1975 Antiques article titled “Joseph B. Barry, Philadelphia Cabinetmaker” cemented that attribution until 2007, when Clark Pearce, Catherine Ebert, and Alexandra Alevizatos Kirtley published a card table from the same shop bearing the chalk signature of Connelly journeyman Robert McGuYn and the date 1807. The later scholars’ analysis of the design and construction of several related tables, including the so-called collector’s table, leaves little doubt that the example illustrated in figure 1 was made in Connelly’s shop.[5]

Although Trump was wrong about the shop responsible for the fabrication of the table, he may have been correct in attributing its carving to William Rush (1756–1833). In “Joseph B. Barry, Philadelphia Cabinet- maker,” Trump cited relationships between the eagles on the table and a sculptural example that Henri Marceau attributed to Rush in his catalogue of the 1937 exhibition William Rush: The First Native American Sculptor (fig. 2). Since the publication of Trump’s article, Marceau’s attribution has been refuted, but no alternative theory about the carver responsible for the table has emerged.[6]

Evidence that Rush carved the eagles on the table can be found in his documented work, most notably a pair of cherubim commissioned by the Grand Lodge of Free and Accepted Masons of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia (fig. 3). A March 1, 1820, entry in the minute book of the building commit- tee appointed after a disastrous fire at the lodge records the decision “to employ William Rush to carve the Cherubims” (fig. 4). Rush received $90 for completing that work the following May. The modeling on the wings of the cherubim and eagles is strikingly similar, displaying almost identical clusters of short feathers at the shoulders and four long feathers extending to the tips. Admittedly, the wings of the cherubim are more robust than those of the eagles, but that may be a function of the size of the cherubim and where they were located within the lodge (figs. 5, 6).[7]

Although it escaped the scrutiny of earlier scholars, many of the table’s design elements relate directly to Royal Arch Masonry, a branch of speculative Freemasonry. The top center compartment has several Masonic symbols (fig. 7). The saltire, more commonly known as a St. Andrew’s cross, bisects the center square and refers to the cross on which St. Andrew was martyred. The cross is associated with York Rite, a grouping of separate rites, including royal arch, and constitutes the jewel of the 29th degree of the Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite, or Grand Scottish Knight of St. Andrew.[8]

At the center of the square is a large sun, surrounded by two crescent moons and what appear to be four stars, in two different styles. In Freemasonry, the sun, moon, and stars represent the officers of the lodge. The sun and its prominence at the center signify the regularity with which the master conducts the business of the lodge. These symbols and their placement are endemic in Masonic art of the early nineteenth century (fig. 8). On the table the sun could also have been intended to represent the all-seeing eye, or eye of Providence, a symbol whose provenance is commonly recognized by non-Masons. The eye is perhaps the most universal of Masonic symbols and invariably appears in visual forms in a place of authority, emitting rays of light. Somewhat problematic, however, is the presence of two moons, rather than one, and four stars rather than seven, the standard iconography.[9]

To the immediate left and right of the sun are two niveaux, French-style levels. Each consists of a stone-block plumb bob suspended from an A-frame. A nearly identical example appears on the title page of The Constitutions of the Antient Fraternity of Free and Accepted Masons (1784). In Freemasonry, the level is both a symbol of equality and a sign for the senior warden of the lodge (figs. 9, 10).[10]

Flanking the top center compartment are paired squares and compasses. When placed together, the tools stand for reason and faith and are among the most prevalent Masonic symbols in American decorative arts (fig. 11). Within each set is a lens, which may represent the vesica pisces. This geo- metric form was first explored by Euclid, whose 47th problem appears regularly as a symbol of the arts and sciences in Freemasonry. The vesica pisces is created by the intersection of two circles and symbolized the possibility for further geometric creation, and creation in general, an interpretation giving it great currency in Christian art.[11]

The bottom center compartment is an oblong, representing the floor plan of the lodge. The diagonal grid created by the mahogany dividers is a clear reference to the black-and-white tiled floor—symbolizing good and evil— of King Solomon’s Temple (fig. 12). Masonic objects have consistently displayed this pattern as the foundation on which all other symbols and marks rest, so it is significant that it is placed at the bottom of the table’s case. At the center of the compartment are three crowns, symbolizing the grand masters of the craft, King Hiram of Tyre, King Solomon, and Hiram Abiff. The coupling of the three crowns with the floor of Solomon’s Temple is evident on Masonic aprons and other objects from the early nineteenth century (fig. 13).[12]

The symbolic intent of the two end compartments is revealed when they are placed side by side. Together they form the Freemason’s keystone—the center stone in the royal arch—and allude to that fraternal group’s origin in craft (figs. 14, 15). As Masonic historian George Steinmetz noted, the division of the keystone into halves is significant:

In its original descent into matter, each ego divided into two halves, each forming a separate entity, the better to learn certain necessary lessons during the numerous incarnations on earth. The keystone of thirty degrees symbolizes one half. When the ego fulfills its destiny and again unites with its other half . . . it is symbolized by two keystones placed side by side and thus is formed one stone of sixty degrees. . . . a sixth part of a circle [sixty degrees] contains an equilateral triangle which is the symbol of the perfect spiritual man.[13]

The mahogany dividers in the side compartments may also have been arranged in a symbolic manner, but at some point they became loose and were reglued without reference to their original design. Regrettably, any meaning this arrangement may have had has been permanently lost.

Because numerology was almost as important as overt symbolism in Freemasonry, the number of veneer segments—fourteen—on the top of the table should not be discounted as a simple stylistic conceit (fig. 16). The number of squares and rectangles created by dark banding in the case’s veneer also totals fourteen. According to James Steven Curl, that number alluded to Masonic historian John Hamilton contends that the number fifteen was much more significant, because there are three, five, and seven steps (for a total of fifteen) on the “winding stairway” to Masonic enlightenment. The half ellipse from which the segments of the top emanate brings the number of veneer components to fifteen, matching the number of reeds in each of the table’s legs.[14]

The most overt symbolism associated with this table has for years been hidden in plain sight—the object itself represents the ark of the covenant. The ark was purportedly kept at King Solomon’s Temple until it was destroyed by the Babylonians and is referred to in the Bible as the chest in which the Ten Commandments were stored. The ark was built as a gilded box, covered by the wings of two cherubim and moved with the aid of two poles held by rings on either side of the case (fig. 17). In a 1904 article T. C. Foote noted that “the ark is said to have been placed under the wings of the cherubim and the cherubim covered the ark.” “Covering” was synonymous with protecting and providing refuge, as indicated in the following passages from the Bible: “under whose wings thou art come to take refuge” (Ruth 2:12); “hide me under the shadow of thy wings” (Psalm 17:8); and “in the shadow of thy wings will I rejoice” (Psalm 63:7).[15]

Because of its association with the word of God, the ark is an important symbol for Royal Arch Masons, who use facsimiles of the chest in lodge ceremonies. In his Freemasons Guide and Compendium, Bernard Jones describes a ceremony wherein “the Captain of the Host opens the Ark of the Covenant brought by the Sojourner from the vault, and found to contain the scroll of parchment bearing the opening words of the Book of Law.” He also notes that “a military lodge, before 1820, possessed an ark in the form of a wood box which traveled with the regiment, and contained the war- rant, jewels, etc., of the lodge.” This table may have held similar documents and accoutrements.[16]

Bills in the archives of the Grand Lodge of Pennsylvania document the use of arks in early-nineteenth-century Masonic ceremonies. In 1811 French émigré upholsterer George Bertault charged $2 for “making the case of the arche.” Eleven years later, Jonathan Stuart received $3.50 for “making a chest for the arch/handles, &c.” Amos Doolittle’s engravings for Jeremy Cross’s The True Masonic Chart, or Hieroglyphic Monitor (1819) suggest that arks commissioned by the grand lodge were displayed beneath the wings of William Rush’s cherubim (figs. 3, 18). There is no evidence that the table was among the furnishings of the grand lodge, but that possibility cannot be discounted given Rush’s probable role in carving the eagles of the table.

Additional evidence that the table was intended to represent the ark of the covenant can be found in period Masonic prints, certificates, aprons, and ceramics. In most instances, the ark is shown either in Solomon’s Temple or beneath the outstretched wings of cherubim. With eagles substituted for cherubim, the table takes on additional symbolism as the ark of the covenant of the early republic.

The purpose this table would have served is unclear, since it could have been commissioned for use in either a Masonic lodge or a private home. Although Masonic rituals were largely sacrosanct, designs and symbols associated with the organization were prevalent in everyday life. Eighteenth and nineteenth-century merchants sold glasses, jewelry, and other objects emblazoned with Masonic emblems to non-Masonic customers as well as members of that order. It is difficult, however, to imagine that the table was not displayed in a lodge or in the home of a prominent Mason. The layers of symbolism manifest in its form and ornament are too numerous and potent to support another interpretation.[17]

Acknowledgements

The author thanks Mark Anderson,Linda Bantel, Dennis Buttleman, Wendy Cooper, William Donnelly, Catherine Ebert, Katherine C. Grier, John Hamilton, Maureen Harper, Brock Jobe, Alexandra Alevizatos Kirtley, Elizabeth Laurent, Aimee Newell, Clark Pearce, and Glenys Waldman.

Joe Kindig Jr. to Henry Francis du Pont, June 27, 1935, Winterthur registration file, 57.945.

Charles Montgomery, American Furniture: The Federal Period, 1785–1825 (New York: Viking, 1966), p. 366.

I am indebted to Clark Pearce for sharing his construction notes on the table.

Montgomery, American Furniture: The Federal Period, 1785–1825, p. 366.

I am grateful to Clark Pearce, Catherine Ebert, and Alexandra Alevizatos Kirtley for sharing research on Connelly and McGuYn, conducted in preparation for their article “From Apprentice to Master: The Life and Career of Philadelphia Cabinetmaker George G. Wright,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Easthampton, Mass.: Antique Collectors’ Club, 2007), pp. 110–31.

Henri Marceau, William Rush: The First Native American Sculptor (Philadelphia: Penn- sylvania Museum of Art, 1937), p. 30. For the case against Marceau’s attribution, see Linda Bantel et al., William Rush, American Sculptor (Philadelphia: Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, 1982), pp. 178–79.

Bantel et al., William Rush, American Sculptor, p. 159.

Albert G. Mackey, An Encyclopedia of Freemasonry and Its Kindred Sciences (Chicago: Masonic History Company, 1921), p. 188.

John Hamilton to Nicholas R. Bell, May 14, 2007.

John Hamilton to Nicholas R. Bell, May 15, 2007; Louis L. Williams and Alphonse Cerza, Masonic Symbols in the American Decorative Arts (Lexington, Mass.: Museum of Our National Heritage, 1976), p. 50.

Williams and Cerza, Masonic Symbols in the American Decorative Arts, p. 52.

John Hamilton to Nicholas R. Bell, May 15 and 17, 2007.

George Steinmetz, The Royal Arch: Its Hidden Meaning (New York: Macoy, 1946), p. 68.

James Steven Curl, The Art and Architecture of Freemasonry: An Introductory Study (London: B. T. Batsford, 1991), p. 237; Hamilton to Bell, May 15, 2007.

T. C. Foote, “The Cherubim and the Ark,” Journal of the American Oriental Society 25 (1904): 279–86.

Bernard E. Jones, Freemasons Guide and Compendium (London: George G. Harrap, 1950), p. 355.

Steven C. Bullock, Revolutionary Brotherhood: Freemasonry and the Transformation of the American Social Order, 1740–1840 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1996), p. 56.