Masonic table attributed to the shop of Henry Connelly, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1806–1810. Mahogany and satinwood with tulip poplar and white pine. H. 39", W. 49", D. 27". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum, bequest of Henry Francis du Pont; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Eagle, probably Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1810–1820. Pine. H. 24 3/4", W. 29 3/4", D. 28". (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art, gift of Thomas A. Andrews, 1889.) This object was attributed to William Rush by Henri Marceau and subsequently used by Robert Trump to attribute the eagles on the table illustrated in fig. 1 to Rush. Marceau’s attribution was refuted in 1982, in the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts exhibition catalogue William Rush, American Sculptor.

William Rush, Cherubim, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1820–1821. Unidentified wood. H. 48", W. 56". (Grand Lodge of Free and Accepted Masons of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Entry for March 1, 1820, in the Minutes of the Building Committee of the Grand Lodge of Free and Accepted Masons of Pennsylvania, 1819–1820. (Masonic Museum and Library of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia; photo, Gavin Ash- worth.) Rush received $90 for the completed work on May 25, 1821.

Detail of the left wing of the cherubim illustrated in fig. 3. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the left wing of the left eagle on the table illustrated in fig. 1. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

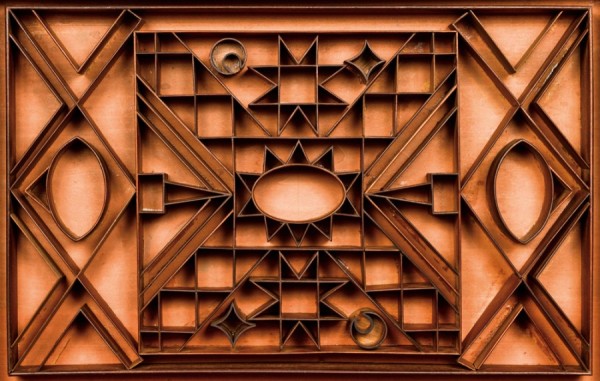

Detail showing the top center compartment of the table illustrated in fig. 1. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The center square is dominated by the saltire, or St. Andrew’s cross. A sun at the center of the cross is flanked by moons and stars. To the left and right of the sun are two niveaux, or French-style levels. Each niveau is composed of an A-frame holding a stone-block plumb bob. Each side of the compartment contains a square, compass, and vesica pisces.

Masonic apron, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1818. Satin-woven silk with silk, metallic, and chenille embroidery. 15 1/2" x 15 1/2". (Masonic Museum and Library of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia; photo, Dennis Buttleman.) This apron depicts the all-seeing eye, sun, moon, and stars.

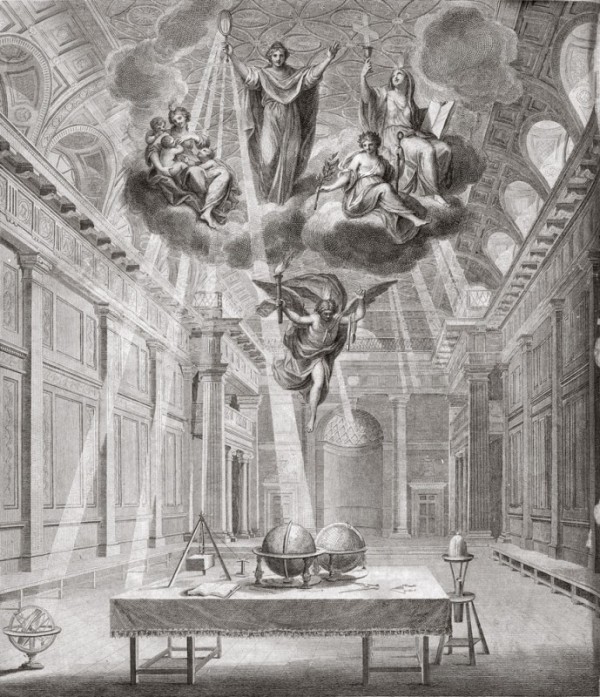

Frontispiece of The Constitutions of the Antient Fraternity of Free and Accepted Masons, 1784. (Courtesy, Scottish Rite Masonic Museum and Library, Van Gorden-Williams Library and Archives; photo, David Bohl.)

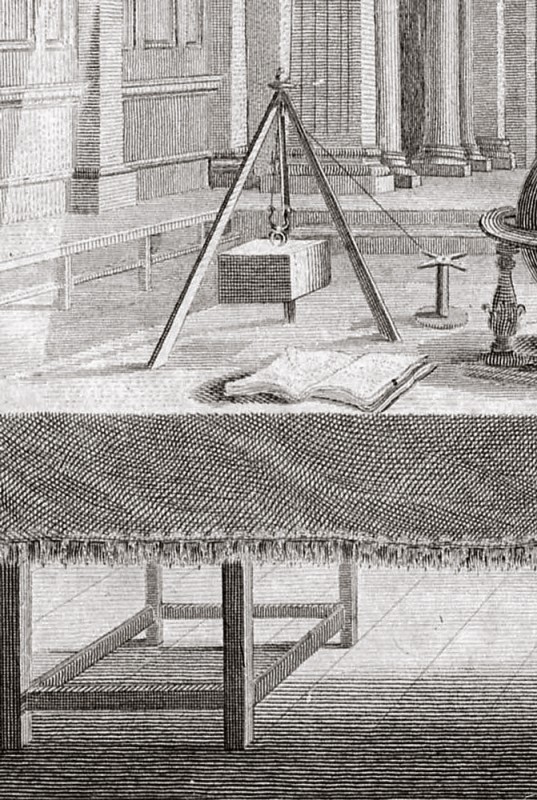

Detail of the frontispiece illustrated in fig. 9. The A-frame niveau with stone-block plumb bob is identical in design to that in the top center compartment (fig. 7) of the table illustrated in fig. 1.

M. Tyler & Co., water cooler, Albany, New York, 1825–1826. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Courtesy, Scottish Rite Masonic Museum and Library; photo, David Bohl.) The square and compass were the most commonly reproduced Masonic symbols in early American decorative arts.

Detail showing the bottom center compartment of the table illustrated in fig. 1. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The diagonal grid represents the black-and-white tiled floor—symbolizing good and evil—in King Solomon’s Temple. The compartment is an oblong, representing the floor plan of the temple and by extension the Masonic lodge. The three crowns stand for King Solomon, King Hiram of Tyre, and Hiram Abiff, the ill-fated architect of Solomon’s temple.

Detail of the apron illustrated in fig. 8 showing three crowns over the temple floor.

Detail showing the side compartments of the table illustrated in fig. 1. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) When the table’s two side compartments are pushed together, they form the royal arch keystone.

Mark medal, Bangor, Maine, 1849. Gold. (Courtesy, Scottish Rite Masonic Museum and Library, gift of Mr. and Mrs. Shattuck W. Osborne; photo, David Bohl.)

Detail of the top of the table illustrated in fig. 1. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

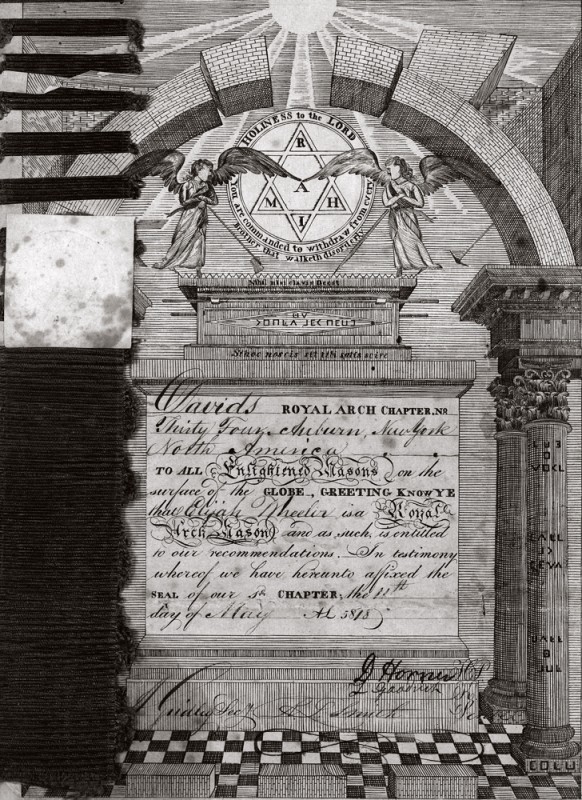

Royal arch certificate attributed to engraver Charles Cushing Wright Homer, New York, ca. 1818. Line engraving on paper. (Courtesy, Scottish Rite Masonic Museum and Library, Van Gorden-Williams Library and Archives, Museum purchase; photo, David Bohl.) Royal arch certificates almost always show the ark of the covenant under the wings of two cherubim.

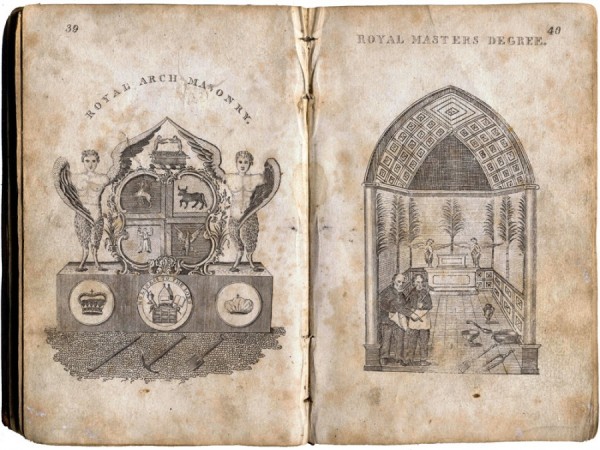

Amos Doolittle, Royal Arch Masonry, Royal Arch Degree, illustrated in pls. 39–40 in Jeremy Cross, The True Masonic Chart, or Hieroglyphic Monitor, 1819. Engravings. (Courtesy, Masonic Museum and Library of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia; photo, Dennis Buttleman.) Two cherubim protect the ark of the covenant with their outstretched wings in these popular royal arch engravings.