Charles Bird King, Joshua Johnson (1742–1802), oil on canvas. (Courtesy, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Adams-Clement Collection, gift of Mary Louisa Clement in memory of her mother, Louisa Catherine Adams.) Johnson is the Annapolis merchant in London who researched Chase’s claim on the Lawrence Street properties and broke the news about the pottery.

Jeremiah Townley Chase (1748–1828), attributed to Robert Edge Pine, ca. 1785, oil on canvas. (Courtesy, Maryland Historical Society, Baltimore, Maryland.) Chase is the American who failed to collect his rents in arrears on the Chelsea Porcelain Manufactory.

Houses in Lawrence Street, Chelsea, London, on the site of the Chelsea Porcelain Manufactory. (Photo, Stephen Patrick.)

Plaque describing the significance of the Chelsea factory in Lawrence Street. (Photo, Stephen Patrick.)

Tureen, Chelsea Porcelain Factory, London, England, ca. 1754. Soft-paste porcelain. H. 10 1/2". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.) The molded and ornamented design of this tureen reflects the silversmith training of Nicholas Sprimont; it is embellished with enamel-painted decoration and gilding attributed to Jefferys Hamett O’Neale. Traditionally thought to have been made for Warren Hastings, now of the Campbell Soup Tureen Collection

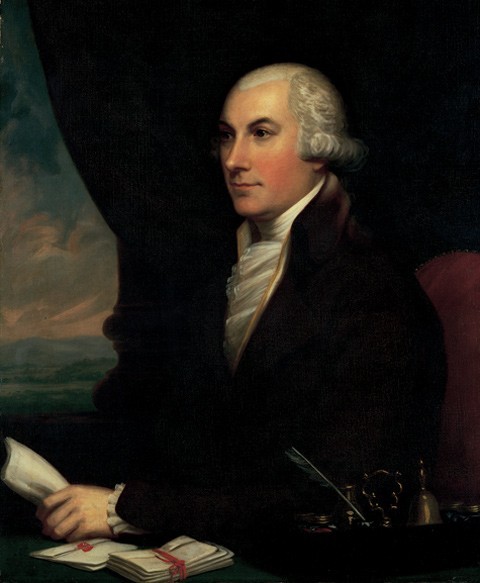

Joshua Johnson (1742–1802), an Annapolis merchant, traveled to London in 1773 (fig. 1). Johnson’s letterbooks reveal that he was engaged by a number of his Annapolis neighbors to act on their behalf in business matters. One of those neighbors engaging his services was Jeremiah Townley Chase (1748–1828), the son of British émigrés from London (fig. 2).

Chase’s mother died when he was five months old, and his father, Richard, followed when the boy was nine. As an adult, Chase read law and prepared for the bar, and later was appointed a Maryland state judge. At the age of twenty-four, in 1773, the young solicitor was becoming increasingly aware of his own legal history and the disposition of his father’s estate when Chase was a child.

In surviving records, Chase apparently encountered a letter written by his father’s cousin, London solicitor Sir William Halton, on December 10, 1747.[1] Sir William referred to London properties that had been given to Richard Chase from his mother’s family, conveyed by settlement around 1720, and included an account of rents paid on houses owned in Wardour Street, Soho (figs. 3, 4). Jeremiah Chase had no prior knowledge of these properties in London, and most certainly had not seen any income. He engaged Johnson to investigate the matter. On December 23, 1775, as the American Revolution began to escalate, Johnson reported back from London, writing to Chase in Annapolis. He cataloged the frustrations he had encountered with various landlords, attorneys, bookkeepers, and clerks, and in the end, engaged a London attorney. He also produced new information:

there were four more houses in the original Richard Chase estate. They were not in London proper, and thus his London attorney had traveled up the river to explore them. Johnson enclosed with his letter to Chase a copy of the attorney’s report, which read in part:

The four Houses at Chelsea are situate at the upper end of Lawrence Street near the church fronting the river Thames and were some years since occupied by the Proprietor of the Chelsea Porcelain Manufactory but are now in the occupation of Mrs. Friend (who inhabits the same house Dr. Smollet did). . . . The Name of Chase is well known to the Person from whom I gathered most of this Intelligence who has lived in Lawrence Street near 30 years and remembers seeing some old leases at the time the Estate was put up to Sale.[2]

After the war, Chase got some money from Wardour Street, but he failed to regain any claim to the Chelsea property, the first home of the celebrated porcelain manufacturer (fig. 5). The lack of documentation hindered him tremendously, and the sale and destruction of the houses in 1784 further frustrated his case, which he pursued into the 1790s. In a letter written in 1873, Judge Chase’s granddaughter, Lucy Harwood, sadly noted, “Grand Pa seems to have had endless trouble with his English estates—his health was always delicate and as it became more infirm I imagine he let the English affairs drop.”[3] Judge Chase died in 1828, a few days shy of his eightieth birthday, never collecting on his Chelsea properties.

Stephen E. Patrick

Director, City of Bowie Museums

<spatrick@cityofbowie.org>

Sir William Halton to Richard Chase, December 10, 1747, Jeremiah T. Chase Papers, MS.278, Box I, File 10, Maryland Historical Society, Baltimore, Maryland.

Joshua Johnson to Jeremiah T. Chase, Joshua Johnson Letterbook, vol. 2, Chancery Exhibits, Acc. 1508, Maryland Hall of Records, Maryland State Archives, Annapolis, Maryland.

Lucy Harwood to Col. Kimmel, Annapolis, September 29, 1873, Jeremiah T. Chase Papers, MS.278, Box 2, File 5, Maryland Historical Society, Baltimore, Maryland.