Newel post attributed to Thomas Day, Littleton Tazewell Hunt House, Milton Township, Caswell County, North Carolina, ca. 1855. (Photo, Tim Buchman.) This is one of twenty-five distinctive S-shaped newels attributed to Day.

Presbyterian Church, Milton, North Carolina, ca. 1837. (Photo, Jerome Bias.)

Detail of the interior of the Presbyterian Church, showing pews made by Thomas Day, Milton, North Carolina, ca. 1837. Walnut with tulip poplar. (Photos, Jerome Bias.) Day joined the church in 1841 but likely made the pews earlier. Rev. Nehemiah Henry Harding served as pastor from 1835 to 1849.

Union Tavern, Milton, North Carolina, ca. 1818. (Photo, Tim Buchman.) Formerly known as the Yellow Tavern, Thomas Day’s home and workshop is on the town’s main street. The tavern was a major stagecoach stop on the route to Petersburg, Virginia.

Newel post attributed to Thomas Day, Woodside, Milton, North Carolina, ca. 1838. (Courtesy, Historic Woodside House; photo, Tim Buchman.) Woodside was built by planter and foundry owner Caleb Hazard Richmond. The house is noted for having interior architectural details fabricated by Thomas Day and for being the site where Confederate general Dodson Ramseur married Richmond’s daughter Mary.

Detail of a newel post attributed to Thomas Day, William Long House, Blanch Community near Milton, North Carolina, ca. 1856. (Photo, Tim Buchman.) This design may have been inspired by Day’s initials.

Detail of a scrolled mirror support on a sideboard attributed to Thomas Day, Milton, North Carolina, 1840–1855. Mahogany and mahogany veneer with yellow pine, tulip poplar, and walnut. (Collection of the North Carolina Museum of History, donation Museum of History Associates and Mr. Thomas S. Erwin; courtesy, Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum; photo, Amy Vaughters.) The sideboard was made for Caleb H. Richmond.

Lounge attributed to Thomas Day, Milton, North Carolina, 1845–1855. Walnut with yellow pine. H. 27 3/8", W. 88 9/16", D. 23 7/16". (Collection of the North Carolina Museum of History, purchase with state funds; photo, North Carolina Museum of History.) Day made twelve documented settees that he referred to as “lounges.” This example descended in the Bass-Engle family.

Sofa attributed to Karsten Petersen, Salem, North Carolina, 1830–1850. Cherry with tulip poplar. H. 25", W. 72", D. 23 1/2". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museum & Gardens.)

Detail of the left term support of a chimneypiece documented to Thomas Day, William Long House, Blanch Community near Milton, North Carolina, ca. 1856. (Photo, Tim Buchman.)

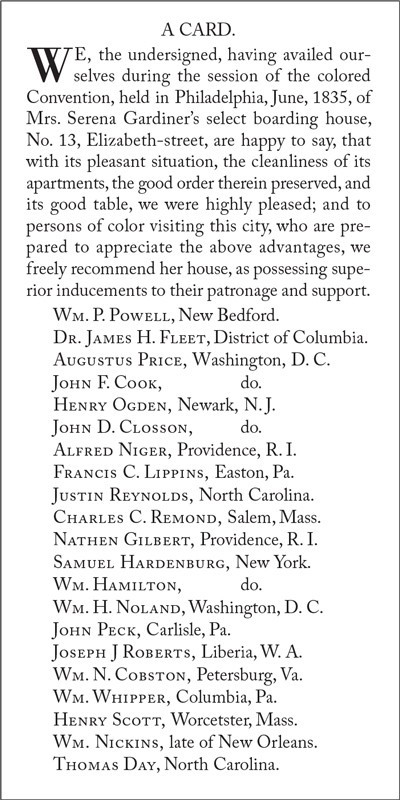

“A Card,” Liberator, August 8, 1835, p. 127. (Facsimile.)

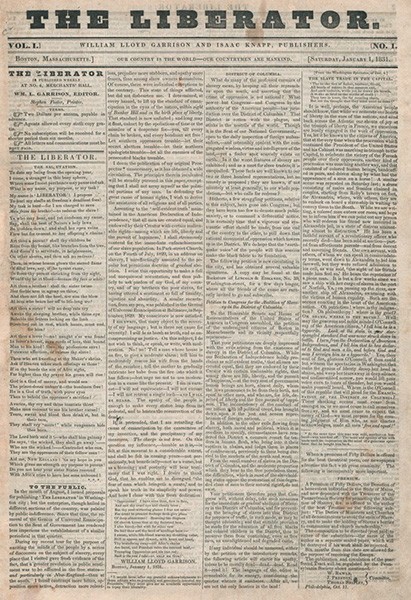

Liberator, January 1, 1831. (Courtesy, Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston, Massachusetts.) The front page of the first edition features William Lloyd Garrison’s famous “Open Letter to the Public,” in which he stated, “I am in earnest—I will not equivocate—I will not excuse—I will not retreat a single inch and I WILL BE HEARD.”

Photograph of William Lloyd Garrison. 3 1/4" x 3". (Courtesy, Prints of American Abolitionists Collection, Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston, Massachusetts.) An uncompromising moralist, Garrison was editor and publisher of the Liberator for more than thirty years and a founder of the American Anti-Slavery Society.

Jeremiah Paul, Manumission of Dinah Nevill, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1795. Oil on canvas. 50" x 39". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This emotionally charged picture depicts Quaker tailor Thomas Harrison purchasing the freedom of “mulatto” slave Dinah Nevill from Benjamin Bannerman, Virginia planter. In 1773 Bannerman bought Nevill and her three children from Nathaniel Lowry of New Jersey and arranged for the family to be transported to Philadelphia. On their arrival in the city, Nevill made a public plea claiming that she and her children were free people. A group of Quakers filed suit to void Bannerman’s claims, but the court ruled in the latter’s favor. This decision and similar cases involving African Americans led to the formation of the Society for the Relief of Negroes Unlawfully Kept in Bondage, which would eventually become the Pennsylvania Abolition Society. Thomas Harrison (1741–1815), who was a founding member of that society, continued the effort to free Nevill and her children, and on May 18, 1779, he manumitted them with money provided by Quaker brewer Samuel Moore.

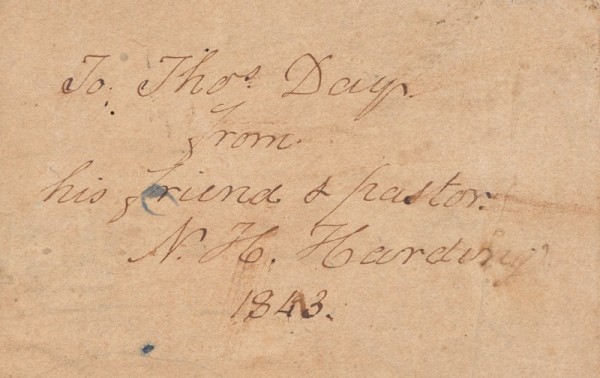

Inscription in Thomas Day’s Bible written by his pastor, Nehemiah Henry Harding. (Collection of Dr. and Mrs. Thomas Baker Day; photo, courtesy, North Carolina Museum of History.)

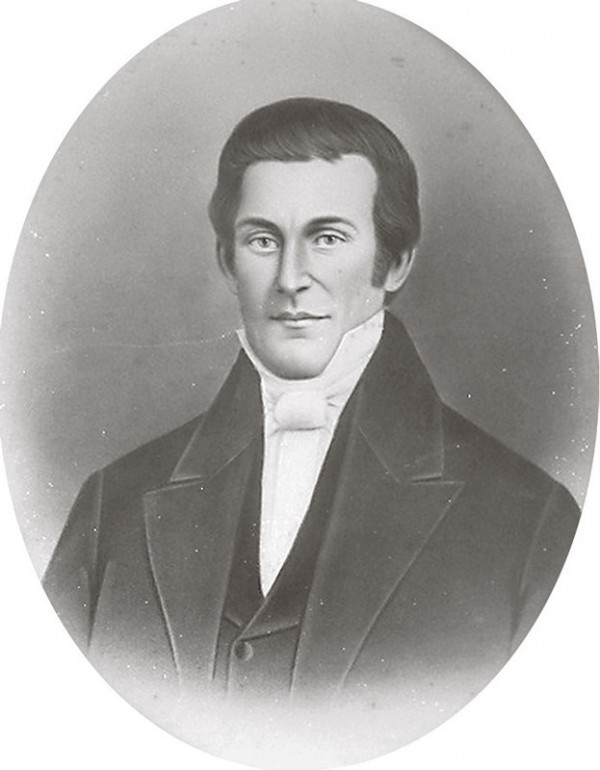

The Reverend Nehemiah Henry Harding. (Courtesy, Presbyterian Heritage Center, Montreat, North Carolina.)

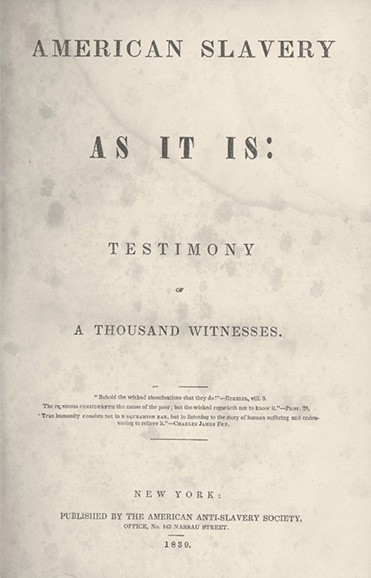

Frontispiece, Theodore Dwight Weld, American Slavery As It Is: Testimony of a Thousand Witnesses, 1839. (Courtesy, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.) This publication is a documentary account of slavery in all its brutality through firsthand testimonials and recollections of former slaves as well as white witnesses. It was distributed widely and is considered one of the most influential antislavery tracts. The Reverend Nehemiah Henry Harding, pastor of the Milton Presbyterian Church and friend of Thomas Day, is represented in the book with a quotation in which he condemns the immorality of slavery as an institution.

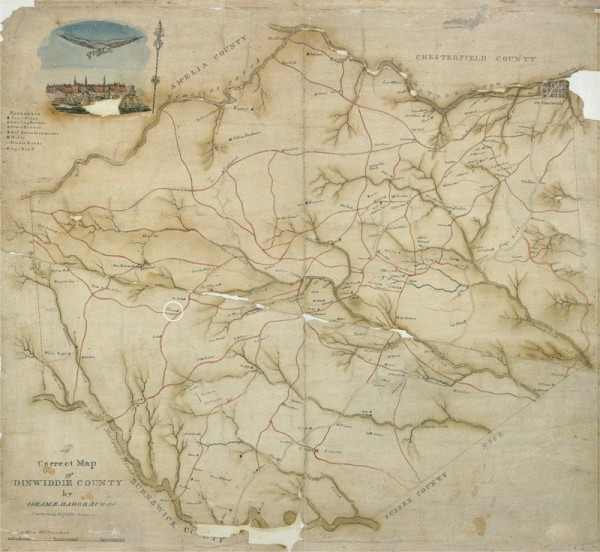

Isham E. Hargrave, “Correct Map of Dinwiddie County, Virginia containing 317,200 acres,” ca. 1820. (Courtesy, Library of Virginia, Richmond, Virginia.) This map shows the “mansion house” of Thomas Day’s maternal grandfather, Dr. Thomas Stewart, on present-day Old White Oak Road. Hargrave was the county’s deputy surveyor.

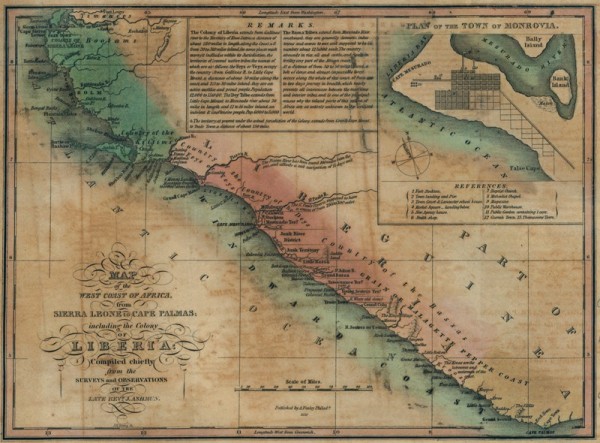

Jehudi Ashmun, “Map of the West Coast of Africa from Sierra Leone to Cape Palmas, including the Colony of Liberia,” printed by A. Finley, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1830. (Courtesy, Geography and Map Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.) Thomas Day’s brother John Day Jr. sailed for Liberia the same year this map was printed. John lived in Monrovia, which is depicted on this map, before embarking on his career as a missionary.

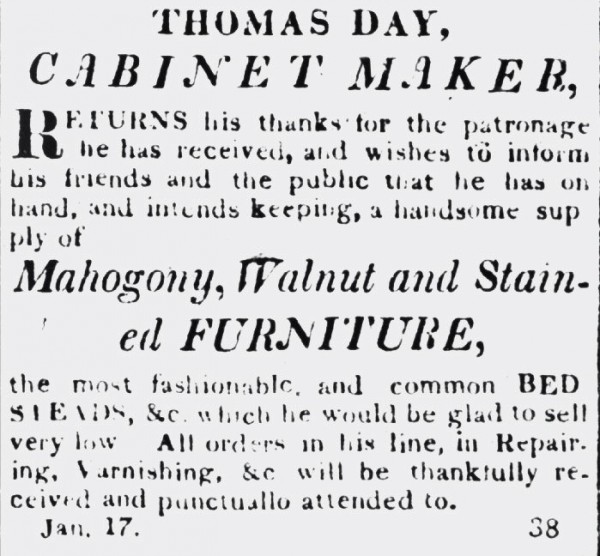

Advertisement for Thomas Day’s shop, Milton Gazette & Roanoke Advertiser, March 1, 1827. (Courtesy, North Carolina Office of Archives and History, Raleigh, North Carolina.)

“Whatnot,” or étagére, attributed to Thomas Day, Milton, North Carolina, 1853–1860. Mahogany and mahogany veneer with yellow pine, tulip poplar, and walnut. H. 69 3/4", W. 40", D. 16". (Private collection; courtesy, Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum; photo, Tim Buchman.) Day made this étagére for Milton merchant John Wilson.

Thomas Day, lady’s open pillar bureau, Milton, North Carolina, 1855. Mahogany and mahogany veneer with yellow pine and tulip poplar. H. 85", W. 42 1/8", D. 20 7/8". (Collection of the North Carolina Museum of History, purchase funds provided by Delta Sigma Theta Sorority, Inc.; Photo, North Carolina Museum of History.) Day made this bureau for former North Carolina governor David S. Reid, who lived in Rockingham County.

Thomas Sully, Joseph Jenkins Roberts (1808–1876), Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1844. Oil on canvas. 33 7/8" x 29 3/8". (Historical Society of Pennsylvania Collection; courtesy, Philadelphia History Museum at the Atwater Kent, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.) Roberts, a Petersburg, Virginia, merchant, was the first president of Liberia and one of the twenty-one men who lodged in Mrs. Gardiner’s Philadelphia boardinghouse during the black abolitionist convention of 1835.

William Whipper, attributed to William Matthew Prior, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1835. Oil on canvas. 24 3/4" x 20 1/8". (Courtesy, Fenimore Art Museum, Cooperstown, New York, gift of Steven C. Clark; photo, Richard Walker.) Whipper was a wealthy Pennsylvania lumber and coal merchant and a founder of the American Moral Reform Society. He delivered the keynote address at the 1835 convention in Philadelphia and signed the “Card,” which places him in the city and the boardinghouse with Thomas Day and John Francis Cook. When a white mob tried to destroy Cook’s school in Washington two months after the convention, he fled to Whipper’s hometown, Columbia, Pennsylvania.

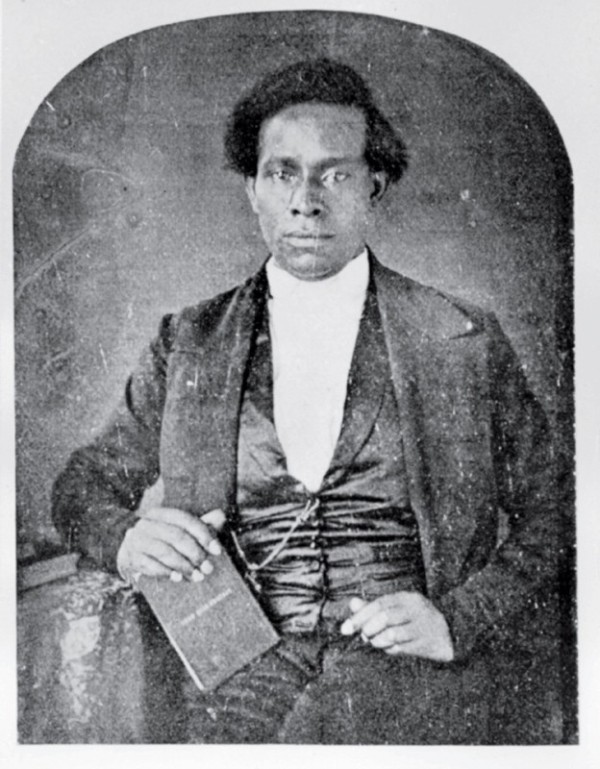

The Reverend John Francis Cook, shown in a copy of a newspaper photograph presented to the Moorland-Spingarn Research Center of Howard University in Washington, D.C. by Cook’s descendants. (Courtesy, Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, Howard University, Washington, D.C.)

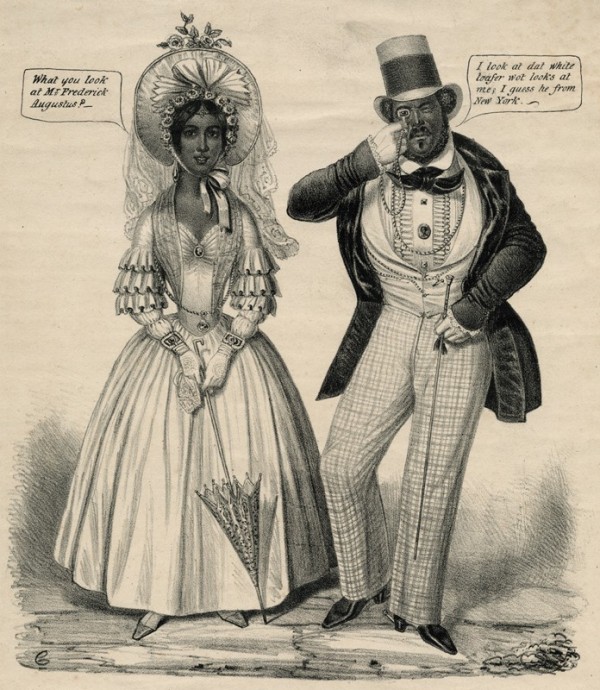

Edward Williams Clay, “Philadelphia Fashions, 1837,” printed and published by H. R. Robinson, New York City, ca. 1837. Lithograph. 18 1/2" x 12 3/4". (Courtesy, The Library Company of Philadelphia.) This image is one of a series of racist cartoons that satirized the dress and manners of Philadelphia’s most affluent African Americans. The male figure is believed to be the well-known barber and social activist Frederick Augustus Hinton and the female, his second wife, Eliza Willson. African American stereotypes such as this were pervasive in mid-nineteenth-century America and reveal that racism was accepted in the North despite the fact that free blacks had more freedoms and greater opportunities there than in the South.

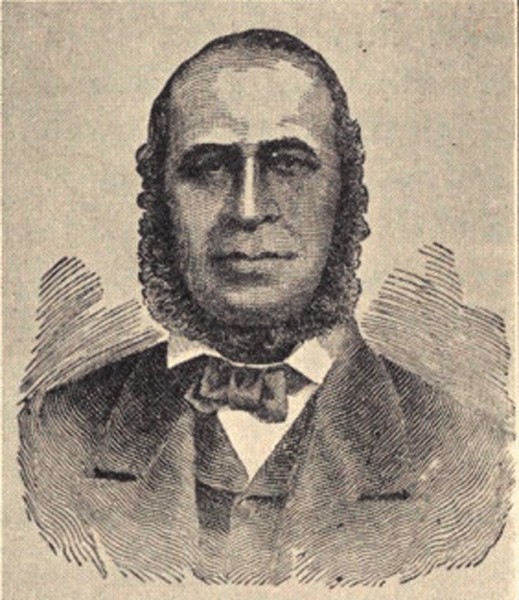

Engraving depicting Charles Bennett Ray, from Carter G. Woodson, The Negro in Our History (Washington, D.C.: Associated Publishers, 1922), p. 146. Ray was a businessman, preacher, and operative with the Underground Railroad. He also served as an agent and later as publisher and editor of the influential black abolitionist newspaper the Colored American, which encouraged the moral, social, and political improvement of African Americans and endorsed a peaceful end to slavery. A native of Falmouth, Massachusetts, he was the first black graduate of Wesleyan Academy in Wilbraham, the same abolitionist-led school where Thomas Day later sent his three children.

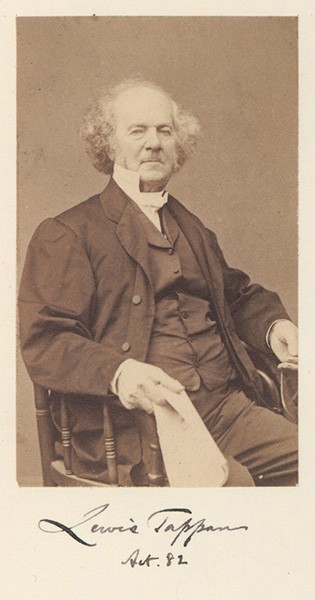

Photograph of Lewis Tappan. 9" x 6" (Courtesy, Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston, Massachusetts, Prints of American Abolitionists Collection.) Tappan, a prominent New York City merchant, and his brother Arthur were among the founders of the American Anti-Slavery Society and their credit-reporting firm was the precursor of Dun & Bradstreet. The diary of the Reverend John Francis Cook of Washington, D.C., reveals that Lewis Tappan was among the many prominent northern abolitionists who corresponded with and visited the minister.

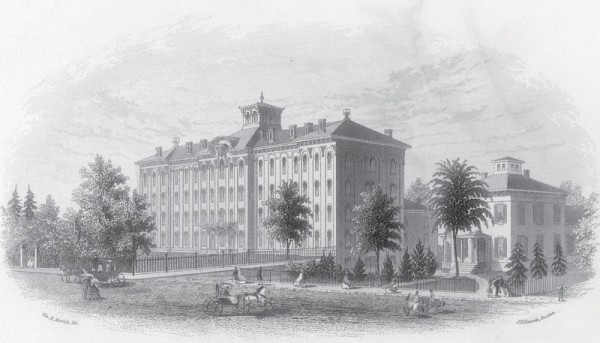

Frontispiece in the Reverend David Sherman, History of the Wesleyan Academy, at Wilbraham, Mass., 1817–1890 (Boston: McDonald & Hill Co., 1893). Thomas Day sent his daughter Mary Ann and younger son, Thomas, to Wesleyan for the 1849–1850 school year. Their brother Devereux joined them there the following term. Thomas Day’s correspondence indicates that he was close to the school’s abolitionist principal, the Reverend Miner Raymond.

Fanny Palmer, “Chatham Square. New York,” for N. Currier. Lithographer, New York City, ca. 1847. Aquatint on paper. Plate, 8" x 12 1/2". (Courtesy, Museum of the City of New York, New York.) W. N. Seymour & Co., the hardware emporium where Thomas Day conducted business for many years, is the white building with the flag in the background.

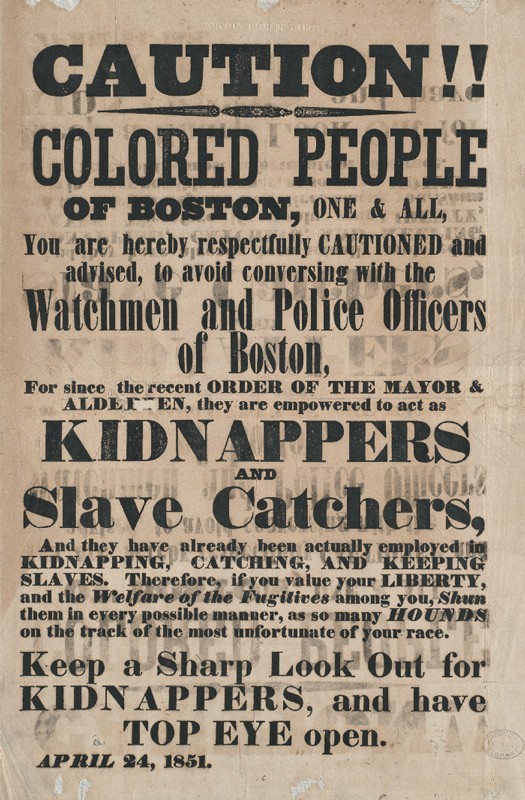

Caution!! Colored People of Boston. Boston, Massachusetts, April 24, 1851. Ink on paper. 16" x 10 1/2". (Courtesy, Trustees of the Boston Public Library/Rare Books Collection.)

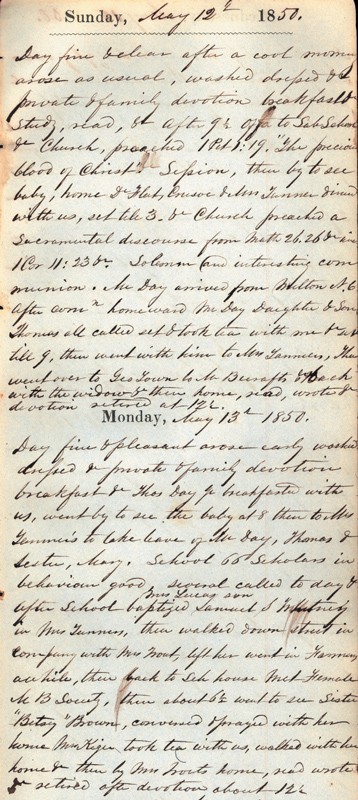

Detail of the Reverend John Francis Cook’s diary entries describing a visit from Thomas Day and two of his children on May 12 and May 13, 1850, box 3, Cook Family Papers, 1827–1869. (Courtesy, Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, Howard University, Washington, D.C.)

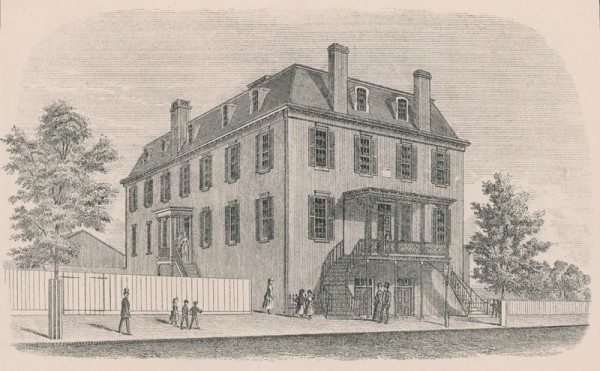

The Stevens School, Washington, D.C., 1870. Copy of an engraving in Annual Report of the Superintendant of Colored Schools of Washington and Georgetown, 1871–2 (Washington, D.C.: National Republican Job Office Print, 1873), frontispiece. (Courtesy, Charles Sumner School Museum and Archives, Washington, D.C.) The District of Columbia’s first public schools for African American children were established in 1867, and the Stevens School, named for radical abolitionist congressman Thaddeus Stevens of Pennsylvania, was built the following year.

Photograph of Annie Day Shepard, ca. 1945. (Archives of North Carolina Central University, Durham, North Carolina.) The granddaughter of Thomas Day, Shepard cofounded North Carolina Central in 1910 with her husband, Dr. James Shepard. She was a college-educated teacher and the namesake of her aunt/stepmother, Annie Washington Day.

Thomas Day, bedstead, Milton, North Carolina, 1853. Mahogany veneer with yellow pine and tulip poplar. H. 87 1/2", L. 82", W. 65 1/2". (Collection of the North Carolina Museum of History, purchase with state funds; photo, North Carolina Museum of History.) Day made this bedstead for Azariah Graves II of Oak Grove plantation in present-day Stony Creek Township, Caswell County, North Carolina.

Passage rack, or hall tree, attributed to Thomas Day, Milton, North Carolina, ca. 1857. Tulip poplar; mahogany graining. H. 86", W. 35", D. 23 1/2". (Courtesy, Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum, gift of Dr. and Mrs. H. W. Moore as part of town renovation of the Ruffin Roulhac House as Hillsborough’s Town Hall; photo, Amy Vaughters.) The rack was made for C. H. Moseley of Caswell County, North Carolina.

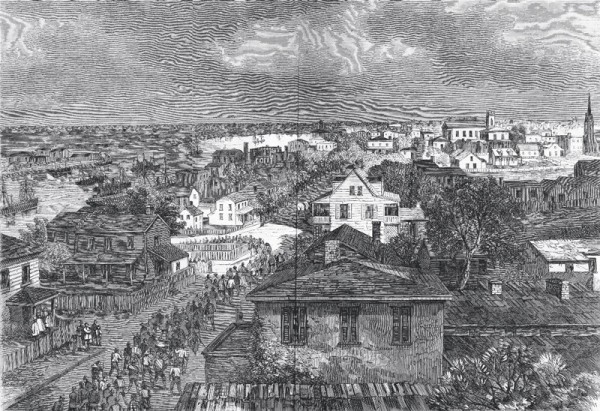

“View of Wilmington with Released Prisoners Marching on Their Way to the Transports, Feb. 27, 1865,” Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, April 1, 1865. (North Carolina Civil War Image Portfolio, Prints and Photographs, North Carolina Collection, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.) The focus of this image is freed Union prisoners of war, Confederate captives, and refugees. The Days were in Wilmington when this image was created.

Late in the spring of 1835, a rising young African American furniture maker from Milton, North Carolina, named Thomas Day (1801–ca. 1861) traveled to Philadelphia (fig. 1). Under normal circumstances, it would have been logical for a professional artisan to visit this bustling commercial hub in search of new business contacts and the latest fashions in furniture making, but circumstances were not normal. After Nat Turner’s bloody insurrection in August 1831, white-on-black violence targeting free blacks and antislavery activity had increased and spread. It was dangerous for any free person of color, let alone a southerner, to be in the so-called City of Brotherly Love, where white mobs had attacked and demolished African American businesses and gathering places in that very year as well as in 1832 and 1834.

Day was in Philadelphia for a different purpose: to attend the Fifth Annual Convention for the Improvement of the Free People of Colour in the United States. This event attracted the nation’s most prominent free African American antislavery leaders, a group described as “men of enterprise and influence” who were on hand to forward an ambitious and wide-ranging platform. In the course of five days, the attendees formally called for improved African American access to schools and jobs and a boycott of sugar produced by slave labor. They railed against the growing number of proposed plans for African colonization by former slaves and free blacks and pledged temperance, thrift, and moral reform. The delegates also vowed to blanket Congress with a pamphlet campaign to outlaw slavery in the District of Columbia “and its territories.” Most emphatically, the group proclaimed its belief in universal liberty and racial equality: “We claim to be American citizens and we will not waste our time by holding converse with those who deny us this privilege unless they first prove that a man is not a citizen of that country in which he was born and reared.”[1]

For a southern person to attend this event was startling enough. For a free person of color who ran a successful business in a small southern market center, going to Philadelphia was a radical act. Had Day’s white neighbors and patrons in the slave-powered tobacco region of Caswell County known of his presence at this historic black abolitionist meeting, he and his family would have been in grave danger. In North Carolina, anyone merely in possession of a pamphlet containing so much as a whiff of abolitionist propaganda risked being accused of sedition, a crime punishable by imprisonment, whipping, and even death. Indeed, in the years leading up to the Civil War, fomenting racial unrest was a felony in that state, and the meeting Day attended could not have posed a more seditious threat to the public order at his home some four hundred miles to the south.[2]

Day’s participation in the convention is all the more remarkable because just five years earlier, North Carolina’s attorney general, Romulus M. Saunders, had informed members of the state legislature that they could trust Thomas Day, who was petitioning for residency status for his African American wife. “In the event of any disturbance amongst the Blacks,” Saunders stated, “I should rely with confidence upon a disclosure from him as he is the owner of slaves himself as well as real estate.” Saunders, a Milton resident, could not have envisioned his accommodating neighbor in a crowd promoting racial uplift and abolition. But Day’s presence there provides evidence of another side to him—a life that he kept hidden from his clients and neighbors. A growing body of evidence reveals that Thomas Day moved within abolitionist circles to a degree that Saunders and his southern white associates never would have imagined. In their eyes not only was he a good local businessman, but he was also a fellow slave owner. Enslaved African Americans worked not only in his furniture shop but also the tobacco fields and timberland that he owned outside Milton. Viewed through a modern lens, Thomas Day seems something of an enigma, a man in the middle whose life, work, and personal convictions regarding the most pressing cultural issue of the day moved back and forth. At the height of his career, he wrote to his daughter admonishing her to be pleased with her lot in Milton. Yet, he sent her and his two sons to Wesleyan Academy (now Wilbraham & Monson Academy), an abolitionist-led boarding school in faraway Wilbraham, Massachusetts.[3]

Since 2009, when the present authors first published this new information about Day’s attendance at the convention in Philadelphia, a number of influential publications and exhibitions about him have come out. All overlook evidence that corroborates Day’s Philadelphia visit and his close personal relationships with known abolitionists who had direct ties to the antislavery movement. The pivotal discovery relating to Day’s abolitionist connections was finding his name on the list of attendees at the event in Philadelphia and the supporting proof of where he sought lodging. A newspaper advertisement called “A Card’’ firmly links him to these black conventioneers, and it first appeared in the July 11, 1835, issue of William Lloyd Garrison’s abolitionist paper, The Liberator. More recently, the discovery of the diary of the Reverend John Francis Cook—a leading black abolitionist and delegate to the 1835 convention—provides further proof of Day’s long-standing ties to African American activists in the North. On May 12, 1850, Cook recorded a visit from Thomas Day of Milton, North Carolina, who was accompanied by two of his children. For historian Ira Berlin, the diary corroborating Day’s ties to Reverend Cook is highly significant. “We had a hint that Day was different because of his connection with the abolitionist school and his trip to the Philadelphia convention confirmed this.” But Cook’s words, he says, “completely change our understanding of Thomas Day” and offer further insight into the complex world of antebellum race relations, especially “relations between southern free people of color and those in the North.” Unearthed during the past seven years while conducting research for a Thomas Day documentary film-in-progress, The Thin Edge of Freedom: Thomas Day and the Free Black Experience, 1800–1860, these bits and pieces of information—the “Card,” Cook’s diary, and Day’s personal correspondence—add up to a new understanding of the cabinetmaker and his world.[4]

For many decades, Thomas Day has been a celebrated historical figure. Thanks to early scholarly work by Carter G. Woodson and John Hope Franklin, this furniture maker’s legacy is well known within African American history circles. He is equally well known in the parts of north-central North Carolina and south-central Virginia where his furniture and architectural work were concentrated. Local interest also can be traced back to popular articles written in the 1920s and 1940s. Using the fading memories of Milton’s “old timers,” Caroline Pell Gunter reported that Day was educated in Boston and Washington. Although that was factually wrong, Gunter’s story greatly expanded recognition of this talented artisan and held a grain of truth. An essay that Day’s great-grandson William A. Robinson wrote for Woodson’s pioneering journal, The Negro History Bulletin, in 1950 shed further light on Day’s history, including the names of his children, the Massachusetts town where their school was located, and his own words—expressed in two previously unknown letters to his daughter. On a visit to Milton, the irony of seeing the town’s “old rotting mansions and formal gardens gone to pot” was not lost on Robinson. When an attempt to purchase a signature sideboard from a descendant of his great-grandfather’s wealthiest client was rebuffed, he reported the white man’s telling response, “We got to hold onto the past.”[5]

In the 1970s Day was the focus of several important exhibitions and academic research projects. Ira Berlin cited Day’s work in his seminal book on free people of color, Slaves without Masters: The Free Negro in the Antebellum South. In 1975 the North Carolina Museum of History acquired eighteen pieces of furniture that Thomas Day was commissioned to make for Governor David Reid. This purchase, generously funded by members of the North Carolina chapter of the national black sorority and service organization Delta Sigma Theta, led to the first major exhibit of his work, “Thomas Day, Cabinetmaker.” Historian Rodney A. Barfield chronicled what was known about Day’s life in the exhibition catalogue in which an endnote contained a surprise: the cabinetmaker’s daughter, Mary Ann, had been educated in the North before she went to school in Wilbraham. Ironically, interest in Day accelerated after 1989, when a fire nearly destroyed his home and workshop. (The ensuing restoration spearheaded by a group of dedicated Milton citizens who organized themselves as the Thomas Day House/Union Tavern Restoration, Inc. garnered national publicity.) An award-winning children’s book published in 1994 was followed by intensive biographical research into Day’s life and family supervised by historian John Hope Franklin. During the course of that research, Laurel Sneed and Christine Westfall of the Thomas Day Education Project identified the cabinetmaker’s birthplace and the rest of his family, including his parents, John and Mourning Stewart Day, his brother, John Day Jr. (a well-known Baptist missionary to Liberia), and his maternal grandfather, Thomas Stewart, a “doctor” from Dinwiddie County, Virginia.[6]

The Day renaissance reached critical mass in 1996 with a second show at the North Carolina Museum of History and a traveling exhibit with eleven pieces attributed to him. When a major North Carolina manufacturer unveiled twenty-four Thomas Day reproductions at the High Point international furniture market, the Washington Post took notice and came up with news of its own: the discovery of the cabinetmaker’s Bible in a Baltimore suburb and the revelation that his daughter-in-law was from the nation’s capital. Annie Washington, later Annie Day, was the first principal of the Stevens School, the premier grammar school for “colored” children in the District of Columbia. The school was named for Thaddeus Stevens, a radical abolitionist congressman from Pennsylvania and champion of the Thirteenth Amendment that ended slavery. Additional explorations of Day’s life and work included critical insights from two candidates for master’s degrees. Janie Leigh Carter transcribed and annotated letters written from Liberia by Day’s older brother John, and Michael A. Paquette, a master cabinetmaker, provided an insider’s perspective on the organization of Day’s shop and business practices. In 1998 the Winterthur Museum held a scholarly symposium on race and ethnicity in American material culture, where decorative arts and material culture scholar Jonathan Prown explored Day’s legacy as a craftsman. In light of recent interpretations, he specifically cautioned against Afro-centric interpretations of Day’s work without firmer scholarly and aesthetic evidence. Prown also suggested that some objects that were being attributed to Day, who typically did not label or sign his pieces, might have been made by other artisans, although perhaps some were initially trained in the maker’s shop.[7]

Today, Thomas Day is in the national spotlight more than ever. Much of the new attention centers on an ambitious exhibition held at the North Carolina Museum of History, “Behind the Veneer: Thomas Day, Master Cabinetmaker,” and the handsome catalogue raisonné that accompanied it, Thomas Day: Master Craftsman and Free Man of Color. The authors, Patricia Phillips Marshall and Jo Ramsay Leimenstoll, raised the subject of his “potential” abolitionist connections but ultimately cast doubt on the issue. A subsequent installation at the Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum provided a more elegantly distilled presentation of Day’s work, focusing on his furniture as art. That exhibition similarly missed the opportunity to discuss the recent discoveries about Day’s multifaceted history and specifically to point out his close personal ties to leading abolitionists in the District of Columbia.[8]

The purpose of this essay is not to focus on Thomas Day’s furniture making legacy but, rather, to add to his historiography the ever growing body of evidence related to his abolitionist ties, which in turn suggest a new way of thinking about Day as both a man and a maker. Added to what is already known, this work strives to illuminate the part of his life that he intentionally kept under wraps for his own protection and that of his family. In the process, it both expands and complicates our understanding of the man and effectively serves as a vital chapter that to date has been excluded from his extraordinary story.

Present-day visitors to the hamlet of Milton, North Carolina—population 166—cannot avoid either hearing about Thomas Day or encountering one of the many local sites associated with him. A common starting point for tours is the red brick Presbyterian Church on Broad Street, where he was not only a member but also made the handsome walnut pews that are still in use today (figs. 2, 3). Church records document his family’s membership from 1841 to 1864. Nearby, the template Day used to make the distinctive S-shaped arms of the pews was discovered during the restoration of the Union Tavern (fig. 4), his former home and workshop. But this is where facts about Day and the pews end and two conflicting oral traditions or interpretations begin.

According to one tale passed down in Milton, Day agreed to make the pews on condition that he would be allowed to sit in the main sanctuary so his slaves could look down from the balcony and see him and his family among the white parishioners. In the other version—told mainly by his descendants—he made the pews with the stipulation that his slaves would be allowed to join him and his family downstairs in the sanctuary. For cultural historian Juanita Holland, these tales reflect two dominant and very different contemporary views. In the first case, Thomas Day is a man who desires to segregate himself from his slaves and to “distance himself from being black,” and in the second, Day was “insinuating himself and those he cared about into the [white-dominated] system as much as he could.”[9]

Thomas Day’s story is full of such contradictions; however, this essay will show that many of them can be explained by the fact that Day led a double life: one among white neighbors and customers who wished to maintain the status quo of race-based slavery, and another life among ardent black and white abolitionists. Day had to behave very differently in those polarized worlds.

Even a cursory glimpse into the world of Thomas Day opens up an understudied and underappreciated aspect of American history: the experience of so-called free African Americans in the generations between the American Revolution and the Civil War. “Free blacks” or “free people of color” constituted a caste that was neither white nor free, though technically they were not enslaved. Their ambiguous status kept them on the alert at all times. In the South in particular, they were considered a threat to the white slave-holding society and were increasingly subjected to restrictive laws designed to keep them under control. Franklin described their experience in North Carolina before the Civil War:

Free blacks in North Carolina, as Thomas Day came into manhood, could not move freely from one community to the other. If you wanted to go from Milton or Yanceyville to Raleigh, you needed permission to do that. And it was dangerous for you to do that, because . . . if you turned up where nobody knew you, it would be assumed that you were a runaway slave, and you had no defense against an accusation that you were a runaway. Now he could be seized, and he could be jailed, and the jailer could advertise that he had taken up a runaway slave. . . . Now if that free black, let’s say it was Thomas Day, said, “I am not a slave, I am free,” they’d say, “Yeah, how’re you going to prove it?” “I can prove it in court.” They’d say, “You have no standing in court. You cannot take an oath. You cannot swear on the Bible because you are not a person.” You see?[10]

Southern states, including North Carolina, enacted repressive laws after widely publicized slave insurrections in Virginia in 1800 and South Carolina in 1822. They clamped down even harder after 1829, when David Walker, a free black North Carolina–born abolitionist in Boston, published a bold call for slaves to rise up and fight for their rights. Walker’s appeal unapologetically justified violence if whites would not acknowledge that slavery was a sin, repent, and embrace African Americans as their brothers in Christian fellowship. In North Carolina, the cluster of restrictive statutes included the “seditious publications” act, which banned any printed material that might “excite insurrection, conspiracy or resistance in slaves or free negroes and persons of colour within the State.” From 1830 on, it was illegal for free people of color to teach a slave to read or write, to marry a slave, to preach in public, to “peddle” goods outside the county in which they lived without a license, or to leave the state for more than ninety days and then seek to reenter. It was also next to impossible to free a slave. Anyone contemplating such an action had to publish intent six weeks in advance, petition the state’s Superior Court, and pay the astronomical sum of “one thousand dollars for each slave named.” The penalty for “concealing,” “harboring” or “helping a slave escape from the state” was “death without benefit of clergy.”[11]

It was in such a legally and socially circumscribed milieu that Day lived and worked for more than three decades, making furniture and architectural components for prominent local planters, merchants, and leading citizens, including former North Carolina governors David Lowry Swain and David Settle Reid. In 1847, when he was president of the University of North Carolina, Swain hired Day for a major project. In 1855 and 1858 Day filled large furniture orders for Reid after the latter had become a U.S. senator. In an era when most free African Americans in the South were illiterate, untrained in a marketable skill, and denigrated as a group, Thomas Day stood out as an educated, accomplished artisan, businessman, and family man whose talent, personal integrity, work ethic, and seeming acceptance of prevailing regional values won him the respect of the white community. Making exceptions for individual free blacks who were upright citizens—contributors to their communities who supported the status quo of white domination or gave the appearance of doing so—was part of the white mind-set in the old South. According to historian Melvin Patrick Ely,

There are always white hardliners who go out of their way to disparage free blacks, declaring that people of African descent can’t possibly succeed as free people. And at the same time you find free blacks and whites doing business together, sometimes marrying, founding churches together, even hitching up wagons and moving west together. So what’s going on is considerable fluidity and inconsistency against the backdrop of a pretty thoroughly repressive system.

Day was certainly treated as an exception, not only because he owned slaves but also because his trade served the needs of the local planter class. In addition to making household furniture, Day’s shop produced cribs, caskets, and architectural components. Although he kept up with the latest designs, Day’s repertoire was innovative and, occasionally, idiosyncratic. His newel posts are unique in being tightly spiraled or formed in a shape resembling his initials (figs. 5, 6). Similarly, some of his otherwise conservatively designed sideboards have exuberant and decidedly oversize ornamental scrolls (fig. 7).[12]

It is likely that Day found inspiration in popular British and American design books, but high-style furniture imported into the piedmont region of North Carolina may also have influenced his work. As Marshall notes, Day “developed his aesthetic vision over time. The majority of his documented furniture dates from 1840 to 1860, roughly the last twenty years of his life. The earliest of these present his interpretations of somewhat staid European American designs, while the later pieces are full of motion.” Day’s work was also shaped by interactions with other regional craftsmen, including the Siewers brothers from Salem in 1838. According to some furniture historians, the “lounges” Day began to produce a few years later resemble contemporaneous Moravian examples in their incorporation of German classical, or Biedermeier, designs (figs. 8, 9). Although Day was receptive to new designs and endeavored to offer his clients the latest furniture fashions, his work remained highly individualistic (fig. 10). For art historian Richard Powell, Day’s work reflects an improvisational impulse analogous to jazz.[13]

The recent exhibition and the publication Thomas Day: Master Craftsman and Free Man of Color offer a much-needed overview of his material legacy as a maker of furniture and architectural detail, but a fuller understanding of his life and work hinges on incorporating the newly found evidence about his abolitionist connections. This essay does not posit that the maker’s progressive social and political sentiments shaped his work, but it does aim to present that side of the story for future scholars to take into account. This new understanding begins with the discovery of the newspaper advertisement in which Day and others praised the amenities of the black boardinghouse they patronized in Philadelphia during the Fifth Convention for the Improvement of the Free People of Colour.

Serena Gardiner, an active member of that city’s large free black community, owned the boardinghouse and provided rooms and meals for twenty-one men, including Thomas Day, for the duration of the convention. These boarders, in turn, signed the “Card” at the end of their stay, recommending her establishment as well as citing their reason for being in the city (fig. 11):

We, the undersigned, having availed ourselves during the session of the colored Convention held in Philadelphia, June 1835 of Mrs. Serena Gardiner’s select boarding house, No. 13, Elizabeth-street, are happy to say, that with its pleasant situation, the cleanliness of its apartments, the good order therein preserved, and its good table, we were highly pleased; and to persons of color visiting this city, who are prepared to appreciate the above advantages, we freely recommend her house, as possessing superior inducements to their patronage and support.

Eager for additional business, Gardiner published the “Card” in the Liberator (figs. 12, 13). It included the names and home states of all the men. Three were from the South, including Day, who appears last on the list as “Thomas Day, North Carolina.” In her exuberance to advertise her business, Gardiner was not thinking that it would be dangerous for these southern men at home to be identified and linked to abolitionists in a national antislavery publication.[14]

Since Day was a common name and other Thomas Days resided in North Carolina, it is fitting that the identity of this person be questioned. Census records show that six men named Thomas Day lived in the state around this time. However, four were white and must be excluded since, with the exception of a handful of well-known white abolitionists named as “honorary delegates,” the convention was black and so was the boardinghouse. No white North Carolinians would have patronized an establishment for “genteel” and/or “respectable persons of color,” as Gardiner and her husband, Peter, characterized it in multiple Liberator ads. Of the two black Thomas Days, the Caswell County cabinetmaker is the only one who fits the professional profile of Gardiner’s elite and educated guests. The only other free black named Thomas Day was an illiterate, impoverished tenant farmer from Person County. His descendant Aaron Day, a noted genealogist, said that his ancestor did not have the means to travel far beyond Person County.[15]

The risk taken by Day in attending the convention cannot be overstated, and he would not have traveled north to meet with high-profile black activists in Philadelphia unless he was seriously interested in their beliefs and policies. The city, with its frequent white-on-black mob violence and escalating attacks on organized antislavery activity, was simply not a safe place for anyone of African descent in the late spring of 1835, and Day was the young parent of at least two children dependent on the well-being of their father.

Evidence of Day’s presence in Philadelphia and his identification as a black abolitionist was hiding in plain sight for more than thirty years in The Black Abolitionist Papers, 1830–1865: A Guide to the Microfilm Edition. Issued before the release of the five-volume print series, The Black Abolitionist Papers, the Guide is an index to the massive collection of microfilmed documents and narratives gathered to identify the most significant black abolitionists in the Americas and the British Isles. The scholarly foreword explains how the activist figures were selected, and the Guide lists Thomas Day and all the guests at Mrs. Gardiner’s boardinghouse. The “Card,” the document that placed them there, has been part of the public record since 1981, when the Guide was published, but until 2009 no researcher had ever identified Thomas Day, the black abolitionist in Philadelphia, as the cabinetmaker from Milton.[16]

The discovery of the “Card” casts new light on Day’s secret life and suggests the need to consider more closely his ancestry and formative years. Until the publication of Sneed and Westfall’s 1995 research report, little was known about Day before his arrival in Milton. Census records indicated that he was born in Virginia but did not specify exactly where he was from or how he ended up in North Carolina. A passing mention of John Day Sr. in the Chancery Court records of Dinwiddie County brought the identities of Thomas’s parents and grandfather to light. Citing “John Day and Mourning, his wife, formerly Mourning Stewart, one of the heirs . . . of Thomas Stewart the elder,” the document contains details pertaining to the estate of a free black man, “Dr. Thomas A. Stewart,” and listed the spouses of his many heirs. It was significant because an eighty-four-year-old woman named “Morning S. Day,” presumably Thomas Day’s mother, was listed in his Milton household in the 1850 census. She and Mourning Stewart Day turned out to be one and the same.[17]

Mourning’s father, Thomas Stewart, like his grandson and namesake Thomas Day, was a prominent member of his community as well as a slaveholder. While not common, free black ownership of slaves was a fact of life not only in the South but also in the North. According to Franklin, “at no time during the antebellum period were free negroes in North Carolina without slaves.” In Stewart’s 1804 will, the first of two, he left a female slave to his grandson, “John Day, the son of Mourning,” which made it clear that Mourning and John Day had a son named John as early as that year. In his study of hundreds of free black families born in Virginia, North Carolina, and South Carolina, genealogist Paul Heinegg listed a John Day, born in 1797, who had immigrated to Liberia and become a well-known missionary and statesman. Because that John Day was identified as a “cabinetmaker,” Heinegg hypothesized that he was Thomas’s brother. Heinegg had no proof of a fraternal relationship between the two Days but cited, as a source, a eulogy for John prepared at the time of his death. It appeared in the African Repository, the mouthpiece of the American Colonization Society, the organization that spearheaded the colonization of Liberia. The eulogy revealed that “Rev. John Day” had begun his work abroad with the “Northern Baptist Board of Missions” but had “subsequently become connected with the Southern Baptist Convention.” From 1847 to 1859 he had served as superintendent for the Southern Baptist Foreign Missions Board and had overseen its missionary work in Sierra Leone, Central Africa, and Liberia “up to the hour of his death.” Heinegg was correct in speculating that John was Thomas’s brother.[18]

John Day was one of the most prolific correspondents of all nineteenth-century Baptist missionaries. He sent more than one hundred letters to the Reverend James B. Taylor, the corresponding secretary of the church’s Foreign Mission Board. One John Day letter, written in 1847, confirmed what the court records from Dinwiddie County had implied: “My mother was the daughter of a coloured man of Dinwiddie County, Virginia, whose name was Thomas Stewart, a medical doctor, but when or how he obtained his education in that profession, I know not.”[19]

Thomas Stewart, Thomas and John Day’s grandfather, was born circa 1727 and was the son of a black man who remains unidentified and a white indentured servant, most likely a woman named Elizabeth Stuard, from whom, by law, he inherited his free legal status. Before the American Revolution, most southern free blacks were the mixed-race progeny of black enslaved or indentured men and white female indentured servants. Invariably identified in his adult years as “Dr. Stewart” in the tax rolls of Dinwiddie and Mecklenburg counties, Virginia, he owned substantial property and was by all accounts a well-known and respected local practitioner. Thomas Day’s mother, Mourning Stewart Day, was the second daughter of at least fourteen children born to Dr. Stewart. She was the first child born after the death of his first wife and was apparently named in commemoration of the mourning period. In his autobiographical 1847 letter, John Day also identified his father as a cabinetmaker named John Day (Sr.). A letter written by the missionary’s widow in 1860 confirmed that John and Thomas Day were brothers.[20]

Thomas Day was born into this respected and well-educated family in rural Dinwiddie County, about twenty-five miles southwest of Petersburg. When he was six years old, his father, John Day Sr., moved the family to neighboring Sussex County, where John Jr., age ten, was boarding with a white acquaintance and being educated by white Baptist tutors. Thomas was apparently sent to the same school as his brother, and their father trained both sons in his trade. The Days moved in 1807, the same year Congress outlawed importation of slaves from Africa, but conditions for free black families in Virginia were precarious at best. Several factors, in addition to the opportunity to educate the sons, could have influenced the family’s decision to move to Sussex, including prospects for work and an opportunity to buy property. Sussex had, in addition to Baptists, sizable Quaker and Methodist populations, and the Days were aware that members of those denominations could be important allies. Between 1784 and 1806, more than seventy-five Quaker and Methodist slaveholders in Sussex County manumitted 378 slaves. During the late eighteenth century, Quakers had become increasingly opposed to slavery (fig. 14), including those in Virginia, which had more free and enslaved people of African descent than any other state. One study shows that as early as 1767, Virginia Quakers were “training enslaved people to be laborers in a free market. Monthly meetings loaned money to African American tradesmen and established apprenticeships for their children.”[21]

Sussex lies northeast of Greensville County, where the family also had strong ties. Free black Days and Stewarts had lived in Greensville since before the American Revolution, and John Day Jr. was born there, at Hick’s Ford (later Hicksford and now Emporia) in 1797. In an autobiographical letter, he claimed that his mixed-race father was the illegitimate son of a white woman and her black coach driver and was born in South Carolina and reared in North Carolina. Greensville County records strongly support, however, the view that John Day Sr. had Virginia roots, like his sons’ maternal grandparents, the Stewarts. Heinegg’s research points to another free black Greensville County man named John Day as the father of John Day Sr. This John Day paid taxes in the county from 1782 until his death in 1802. More to the point, he owned properties adjacent to known acquaintances of the free black Days, members of the Robinson and Jeffreys families.[22]

John and Thomas Day came of age during tumultuous times that included white retaliation for slave uprisings in which free blacks were often implicated for no reason other than they were already free. By the second decade of the nineteenth century, gradual improvements in roads and transportation had increased the flow of manufactured products, as large urban shops sold domestic goods and furniture through wider networks. This, in turn, affected many local artisans who could not compete with cheaper, and often more fashionable, factory-made products, including furniture. John Day Sr. was one of the artisans who had a hard time staying ahead financially, in part because he developed a drinking problem. John Jr. later recalled his own youthful efforts to keep his head above water after his father became “intemperate”:

In 1817 my father went over to North Carolina and left me in Dinwiddie to pay a debt he owed to Mr. John Bolling. I carryed on a little cabinetmaking business in a village in that part of the county . . . paid my father’s debt, and was likely to do well in the world’s estimation, but associating myself with—young white men, who were fond of playing cards, contracted that habit. Mr. John L. Scott, a merchant and friend of mine came . . . to see me and I told him that if I continued in that place . . . I should ruin myself. He procured a shop for me about 7 miles off of Mrs. Ann Pryor’s. I commenced well . . . but a drunken journeyman set fire to my shop and consumed all I had. The neighbors spoke of reinstating me, but I would not accept any thing but a coat and hat of my friend J. L. Scott. I went on my feet to Warren County, North Carolina and got in possession of my father’s tools, borrowed money off a gentleman, and commenced work there.

It is not clear where Thomas and his mother were while John Jr. was working off the debt. Possibly Thomas worked for his father in North Carolina or spent some of the time helping his older brother meet family obligations while honing his own cabinetmaking skills.[23]

Research initiated in 1996 explored three centuries of Day family history and led to the discovery of Thomas Day’s Bible, which was in the possession of his great-great-great-grandson Thomas Day V (fig. 15). Like many family Bibles, Thomas’s is full of names and dates, including that of Annie Washington Day, that establish Thomas Day’s connections to people in the North, including leading abolitionists. One of the most important names was that of N. H. Harding, who inscribed the Bible in 1843 and identified himself as Day’s “friend and pastor.”[24]

As noted by historian Peter H. Wood, “if Thomas Day offers one window into the complex world of antebellum race relations, his minister provides another.” The Reverend Nehemiah Henry Harding, the minister of the Milton Presbyterian Church and a graduate of Princeton Theological Seminary, was from New England (fig. 16). The scion of a family of seafaring merchants, he experienced a shipboard conversion during a storm and changed careers. He arrived in Milton in 1835, the same year that Thomas Day attended the black convention in Philadelphia. “Slavery was the most controversial issue of the day,” says Wood, “and everyone had strong opinions. Advocates could be found for armed revolt, peaceful petitioning, immediate freedom, gradual emancipation, African colonization or continued enslavement. As controversy swirled, individuals shifted their stance on the matter.” This is particularly clear in the case of Harding, who “wrestled with this thorny issue.” In the 1830s, on visits home to Brunswick, Maine, the abolitionist hotbed where Harriet Beecher Stowe would later write Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Harding’s position on slavery continued to evolve. On one visit, after a decade of living in a slave state, he said he was “pro slavery” when a Congregational minister asked where he stood. But, after returning to the South, he wrote back to the minister and said that he had experienced a change of heart. “After mature deliberation,” Harding insisted, “I am now a strong-antislavery man . . . the sworn enemy of slavery in all its forms and with all its evils.” During a subsequent visit north, he shifted course again and made what northern activists considered to be “‘gratuitous and invidious remarks about the increasing militancy of abolitionists.’ Asked to read an announcement addressing ‘the duty of Christians . . . toward the colored people’ he refused and preached a sermon warning Brunswick’s citizens to beware of excessive zeal regarding their ‘duty to the colored people.’” Harding likely assumed the changing story was playing out only in his inner circle, but his vacillations became public when a local antislavery advocate printed his letter in the Liberator in 1838 and parts of the letter were extracted and republished by Theodore Dwight Weld in the influential American Anti-Slavery Society publication, American Slavery As It Is: Testimony of a Thousand Witnesses (fig. 17):

I am greatly surprised that I should in any form have been the apologist of a system so full of deadly poison to all holiness and benevolence as slavery—the concocted essence of fraud, selfishness and cold-hearted tyranny and the fruitful parent of unnumbered evils to the oppressor and the oppressed, the one thousandth part of which has never been brought to the light.

According to Wood, the influence of the book in which Harding’s harsh condemnation of the institution of slavery appeared was second only to Uncle Tom’s Cabin. “Perhaps Harding’s views changed again during the last decade of his life through interaction with his most prominent black parishioner. . . . After all, he and Thomas Day were learning from experience that racial enslavement in the United States might outlast them both and that they needed to be guarded in their stated public opinions if they were to endure and prosper in North Carolina.”[25]

Racial enslavement was indeed deeply rooted in the upper South and also in Thomas Day’s own family, going back to his maternal grandfather and slave owner Thomas Stewart. Recent research into Day’s formative years has uncovered an 1820 map of Dinwiddie County that pinpoints his birthplace: Thomas Stewart’s homestead (fig. 18). The search also yielded the first contemporaneous confirmation of Stewart’s medical practice, which appeared in the November 13, 1778, edition of the Virginia Gazette:

I Nathaniel Hobbs of Dinwiddie County do hereby certify, that in the month of May last my negro boy Tom received a kick from a stallion in the forehead, which deprived him of his senses from Sunday until Tuesday evening in which time he lost a quantity of blood, and many ounces of matter, supposed to be part of his brain, but by the assistance of Dr. Thomas Stewart, of Dinwiddie, and his specifick balsam, he is now perfectly well and as sound and sensible as ever.

Beyond dispensing patent medicines, Stewart was a successful farmer and entrepreneur. He also was a free person of color who achieved a surprising level of success and who passed on his ideals and love of learning to his offspring and grandchildren. Details culled from the chancery proceedings and property records revealed that, in addition to large tracts of land, he owned a mill and a popular tavern located in his “mansion house.” He ran these diverse operations with the help of his family and numerous enslaved workers.[26]

In 1810, the year he died, Stewart owned more than nine hundred acres in Dinwiddie County and, at the peak of his ownership, may have had as many as thirty-two slaves. His upward mobility undoubtedly was largely achieved through some combination of talent, resolve, and good fortune. However, the ownership of enslaved men, women, and children was another central factor in his climb, and this raised obvious questions about the mixed-race doctor’s relationship with his slaves. Evidence suggests that Stewart’s connection to his enslaved workers was not as exploitative as one might expect, given his driving ambition. In his 1804 will, he listed twenty-seven slaves by name and requested that sixteen of them be freed on his death. He also asked that some unnamed boys “whom I have emancipated” each be sent to school and then trained in a “good trade.” The will was contested by “divers witnesses,” likely family members to whom the slaves were more valuable as property that could be sold, and, based on their testimony, the court refused to admit the will to the record. After Stewart’s death, twenty slaves he named in his will sued his heirs for their freedom but, ultimately, were unsuccessful in court.[27]

By 1820 both John and Thomas Day were in North Carolina living with their parents in a place identified in early census records as the Nutbush Voting District. This rural area lies in modern Bullocksville in what is now Vance County but was then part of Warren County. During this period, as in earlier generations, many free blacks crossed the Virginia border, heading south to escape escalating racist laws in the Old Dominion and to find cheaper, more fertile land in North Carolina. Soil depletion, the result of decades of tobacco cultivation, was another factor that compelled movement out of Southside Virginia. In John Day Sr.’s case, finding work was the likely motive. Many fine houses were built in the Nutbush region, and the inventory of tools from his 1832 estate papers suggests he was a house joiner as well as a furniture maker.[28]

In 1821 the Day brothers left Nutbush. Thomas, then twenty years old, went to Hillsborough, North Carolina’s former capital. He opened a furniture-making shop, which he described in an advertisement as a “Stand,” where he produced walnut and mahogany furniture. John Jr. moved to Milton, forty miles north of Hillsborough, to begin formal training to become a Baptist preacher. After completing his studies, however, white Baptist examiners accused him of misinterpreting church doctrine and refused to admit him to their ranks. It was a particularly disillusioning setback, and John strongly believed that he had been disapproved on spurious grounds. With a wife and young family to support, he needed to find a different way to uphold his beliefs and find his way in the world. One prospect was to leave America.

Many disheartened free blacks were drawn to the idea of migrating to Africa after the formation of the American Colonization Society in 1816. This did not reflect disloyalty to America but, rather, a loss of hope that Americans of African descent would ever be treated equally in the United States. “We love this country and its liberties,” wrote a free black man in Illinois, “if we could share an equal right in them.” White politicians who feared slave unrest, especially in the South, endorsed the idea of resettlement. In the dozen years after the American Colonization Society acquired control of Liberia in West Africa, more than 250 colonization societies sprang up across the South (fig. 19). Quakers and other religious sects initially supported colonization as a humane alternative to racial oppression in the United States. Eventually, however, many early supporters rejected the colonization movement as a racist scheme to rid the country of African Americans. Yet, along with nearly four thousand other free people of color from Virginia, John Day pulled up stakes and took his family to Africa in 1830, and over the course of the next half century, nearly fifteen thousand free black Americans did the same. The manifest of the ship on which Day traveled listed his occupation as cabinetmaker. In the years that followed, he emerged as a major religious and political leader, a proponent of Liberian colonization, and a critic of the institution of slavery.[29]

Historian Jill Baskin Schade recently discovered evidence that John Day initially worked as a cabinetmaker in Monrovia and that some of his furniture was exported to the American market. A March 1835 advertisement in the African Repository listed “African curiosities,” including furniture made of Liberian wood by John Day, “a first rate cabinet-maker.” Another advertisement placed in May 1836 reported that orders had been received from Baltimore and that two worktables had been shipped. Day’s work as a missionary appears to have begun just two months later.[30]

Thomas Day had moved to Milton in the mid-1820s, and he remained in North Carolina. Perhaps recalling the ways that his grandfather had successfully navigated a slave-based society, he invested in the American free enterprise system despite its glaring inequalities. Day must have realized that in order to thrive in the South as a free person of color, he had to position himself as a part of mainstream society. He bought property in Milton and in 1827 opened a furniture-making shop. In an early advertisement in the Milton Gazette & Roanoke Advertiser, Day thanked his patrons for their furniture orders and assured them of punctual service (fig. 20). By this time, it appears that he was already a well-known and respected figure, one who gained unusual support from North Carolina’s white political class.[31]

In 1826 the North Carolina state legislature enacted a law barring free blacks from entering the state. The law stipulated a $500.00 penalty, and anyone unable to pay could “be held in servitude” for up to ten years. After marrying Aquilla Wilson, a free black woman from nearby Halifax County, Virginia, on January 6, 1830, Day solicited help from his white neighbors, sixty-one of whom signed a petition requesting an exemption for his wife. The most prominent signature was that of Attorney General Saunders on the accompanying affidavit. This remarkable imprimatur from the state’s highest legal authority not only expedited Day’s legal request but also legitimized him in the eyes of the most powerful members of the state’s gentry.[32]

The petition offers a telling example of the complicated and, at times, seemingly counterintuitive ways in which Day needed to operate in order to ensure his own financial success and local acceptance of his family. In the North, free African Americans and former slaves, like Frederick Douglass, who escaped enslavement in Maryland in 1838, could risk taking strong public stands against slavery. Day’s situation, below the Mason-Dixon Line, however, was far more precarious and required subtle forms of resistance. According to Ira Berlin:

He [Day] accepts the law but requests exceptional treatment. This makes him different from someone like Douglass who challenges the legal system and demands the abolition of slavery and the discriminatory racist laws that support it. . . . We see a “personal” approach—enlisting one’s customers and neighbors rather than . . . directly challenging the . . . system.[33]

As with many other successful African American business people, Day developed strategies that allowed him to live and work within the prevailing system and thrive as a member of the local community. By all outward accounts, he appeared to be someone who played by the rules of the day and did not stray too far afield from accepted social practice. But as was the case with many other free people of color, Day seems to have led a far more complicated life, one that was characterized by covert actions and beliefs that ran counter to his public persona.

Political scientist James C. Scott provides useful terms to describe the ways that subordinate groups, including free and enslaved African Americans during the antebellum period, resisted domination and found ways to survive and live within extremely constrained, inhumane circumstances. Scott’s theory spells out the universal practice of marginalized people who pretend to support their suppressors and their institutions rather than suffer the dire consequences they would incur with overt challenges. They protect themselves by wearing a “mask” of accommodation. In North Carolina, a frontal attack on racist laws by a black man would have provoked certain retaliation. Scott calls the professed acceptance of the status quo a “public transcript,” and what subordinated people actually say and do behind their suppressors’ backs, a “hidden transcript.” From his perspective, Day and other free blacks in the South were forced to create a “public transcript,” as both political strategy and survival tactic. Day’s apparent acceptance of state law and his personal petition for his wife’s exemption from it did not overtly threaten the racist status quo. Instead, the petition demonstrated that he was willing to work within the established system. Basing their actions on the side of Thomas Day they thought they knew, the leading citizens of Milton had publicly attested to their belief that he seemed cautious and accommodating on racial matters, unwilling to organize with others openly to fight long-standing discrimination. Scott takes note of the “immense political terrain that lies between quiescence and revolt.” It is this political “middle ground” between complete acquiescence and outright defiance that Day and many other free blacks in the South cultivated for their survival.[34]

Had Day lived long enough or written more, scholars today might have clearer insight into his true feelings about slavery as well as his strategies for navigating society in Milton. Despite lack of access to whatever thoughts he privately entertained, some understanding can be gleaned from a variety of historical sources. The furniture maker’s sole specific pronouncement on the subject is ambiguous. When his daughter Mary Ann blamed her older brother Devereux’s “depraved” behavior on being raised in a “shop of the meanest of God’s avocation,” Day rose to his own defense, praising the “respectable” character of the shop and the honesty of its “hands,” many of whom were not slaves at that time. Mary Ann went on to claim that “being born in the Oppressive South has had a miserable influence on our family.” Again, Day assumed the mantle of a loving father who seemingly was content with the world that he had created for his family: “It pleased the Lord to create Adam and Eve in Eden & it also pleased the Lord to permit you to [be] born in Milton & the best thing you do will be to improve the privileges before you and make yourself acquainted with useful learning and embrace all possible opportunities for spiritual and temporal knowledge.”[35]

Day’s measured response indicates that he understood his marginalized position and the necessity of being well regarded by white elites. However, some of his comments are open to different interpretations. In a letter to Mary Ann, Day wrote, “Ever regard your Caracter more than your life.” Although this can be read as an admonition to maintain respectability at all costs, he may have been advising his daughter, in somewhat veiled manner, to remain true to her own values no matter what situation arises. Maintaining an unassailable reputation was the best protection for Day and his family. Ownership of slaves gave him something in common with his white neighbors and reaffirmed their belief that he was an exception to the prevailing assumption of white superiority and black inferiority. Yet, just as Day’s writings are more complicated than they first appear, so too was his ownership of slaves. The respect accorded to Day by fellow African Americans and white activists in the abolitionist cause suggests motives other than profit and self-protection.[36]

Slavery was pervasive in the South, and free African Americans of means—almost all, like Day, of mixed racial heritage and appearance—were often active participants. Southern whites were three times more likely to own slaves than southern free blacks, a group that constituted a relatively small percentage of the total population, but in 1830 in North Carolina alone, nearly two hundred free blacks owned slaves. According to historian Juliet E. K. Walker, a leading scholar of the African American business tradition, “Facing competition from slave-owning white craftsmen, free black craftsmen needed slave ownership to have any chance of success. In a slave owning society, was there an alternative to unpaid labor?” Slave ownership also guaranteed a dependable source of labor that, in Day’s case, could be supplemented with hired help when a particular job paid enough to justify it.[37]

One of the challenges to understanding ownership of slaves by free blacks is interpreting and weighing the evidence. Most information pertaining to slaves in free black households comes from census records, which are notoriously prone to error. Census takers did not require the person being interviewed to provide documentation regarding the number of family members and/or slaves in a household or their ages. And because slave ownership was one of the best ways for free blacks to demonstrate compliance with the prevailing social system, it was in their best interest to report and even inflate the numbers of slaves they owned. Increasingly, historians are giving credence to this “self-protection” motive. Of course, owners had to pay property tax on slaves claimed to be in their possession, but for a free African American living in the racist South, that “insurance” may have been well worth the price.

Thomas Day took a hands-on approach to his business, acting as workshop manager, craftsman, and salesman. As the owner of his shop, he employed whites and free blacks as well as slaves throughout his career (figs. 21, 22). When he recruited five white Moravian artisans, including the Siewers brothers from Salem at the end of the 1830s, Day owned three slaves and employed “some fifteen hands, both white and colored.” Records show that he owned slaves for at least three decades, increasing his holdings from two in 1830 to fourteen at the apex of his career in 1850. The “Slave Schedule” for the U.S. census that year indicates that six of the fourteen were males between the ages of fifteen and thirty and four were children under ten, the youngest being seven years old. According to this same census, five of the seven cabinetmakers in the shop were white, the only free blacks being Day and his seventeen-year-old son Devereux, both designated mulatto or mixed race. By 1860 he was one of only eight free black slaveholders remaining in North Carolina, with two slaves listed in residence and one as fugitive. Many free blacks left the state in the decades before the Civil War as a result of increasingly constricting social and economic conditions.[38]

Day bravely countered the rising racial restrictions by traveling beyond the scrutiny of white Milton, in part to explore what the abolitionist movement had to offer, including educational and professional opportunities. The 1835 convention, which took place at Philadelphia’s second largest black church, had been heavily promoted in the abolitionist press, and the city was packed with attendees who “despite their wealth and degree of refinement . . . could not be sure of getting a room in one of Philadelphia’s hotels.” Eleven of Serena Gardiner’s guests were official delegates, and three had been delegates to previous conventions, as had her husband. In addition to Day, the gentlemen she listed included Charles Lenox Remond, a fiery orator from Salem, Massachusetts, and a regular on the international antislavery lecture circuit; Joseph Jenkins Roberts of Monrovia, the future first and seventh president of Liberia and close friend of the Reverend John Day; William Hamilton of New York, the keynote speaker at the previous convention; Samuel Hardenburgh, also from New York, grand marshal in the parade that marked the end of slavery in New York State; and William Whipper, a Pennsylvania coal and lumber merchant, one of the wealthiest free black men in America (figs. 23, 24). Whipper operated a major Underground Railroad station in Columbia, Pennsylvania, for more than twenty years, often concealing fugitive slaves in his company’s shipping cars. After slavery ended and he was safe to discuss his role, he described his home, a safe harbor at the end of a bridge across the Susquehanna, as a main “point of entry” for fugitives fleeing Maryland and Virginia.[39]

Others who signed the “Card” included three Washington, D.C., delegates: Dr. James H. Fleet, John Francis Cook, and Augustus Price. An accomplished music teacher, Fleet was “conceded to be the foremost colored man in culture, in intellectual force and general influence in the District at that time.” Cook was a former slave who devoted his life to educating black children and in 1841 founded the esteemed Washington institution now known as the Fifteenth Street Presbyterian Church (fig. 25). Emancipated two and a half years before the Philadelphia convocation, he served as its secretary and was an organizer of the American Moral Reform Society. (Its formation was a centerpiece of the 1835 convention, and the organization actually superseded the convention originally planned for the following year.)[40]

Cook, born in 1810, came from a family of activists. His aunt Alethia Browning Tanner purchased her own freedom and that of at least eighteen friends and relatives, including Cook, his mother, and his siblings. She was an astute real estate investor and a leader of Washington’s early free black community. She also purchased slaves with the express purpose of setting them free. Cook’s uncle George Bell cofounded the city’s first school for colored children in 1807. Cook’s son George later became the first superintendent of the District’s “colored schools,” and his son John served as the city’s tax collector and represented the city at three Republican National Conventions during Reconstruction. At the time of the convention, Augustus Price, a co-author of Whipper’s keynote speech—the American Moral Reform Society’s manifesto—was an aide to Andrew Jackson, the sitting president of the United States. Described as “the president’s trusted servant,” “private secretary,” and “White House doorkeeper,” Price was “present at private White House meetings and cabinet discussions” and also “apparently helped the president draft important documents.”[41]

Cook and Price were deeply involved in local abolitionist efforts. Cook had organized a secret debating club, where he led passionate antislavery discussions and distributed “seditious” publications such as the Liberator to young blacks. Following the June convention, he “breathed the gospel of freedom and reform as never before . . . and told them that white Americans and their laws sorely abused them as people of color.” That August Washington experienced its first major episode of white mob violence against African Americans. Hundreds of armed white men attacked black people, and both Price and Cook were targeted. After his school was nearly destroyed, Cook fled the city on horseback and headed for Columbia, Pennsylvania, where his friend William Whipper resided. For distributing incendiary papers “from the North,” Price was chased by an angry mob that threatened to “enter and search the White House” for him. Price was admitted but the mob was stopped at the door.[42]

While attending the 1835 convention, Day must have been struck by the cultural contrasts between Milton and Philadelphia. The northern city had a large free black population and was the birthplace of the first abolition society established in the western world. By 1838 the city was home to sixteen black churches, twenty-three day schools, four literary societies, three debating societies, three libraries, four temperance societies, and eighty relief or beneficial organizations. It would be difficult to imagine Day not visiting one or more of these organizations, socializing with activists developing the convention platform at Mrs. Gardiner’s boardinghouse, or seeking out local power brokers who once called North Carolina home.[43]

A short list of transplanted North Carolinians living in Philadelphia at this time included former slave Frederick Augustus Hinton, a prosperous barber from Raleigh; Hinton’s father-in-law, oyster seller Richard Howell; and Junius C. Morel, a militant writer and educator (fig. 26). All had close ties to the black convention movement since 1830, when forty free black leaders gathered in the city to form the American Society of Free Persons of Colour. (Morel and Richard Allen, founder of the African Methodist Episcopal Church, wrote and signed the manifesto that called for the first official convention in 1831 and promoted immigrating to Canada rather than Liberia.) Historian Julie Winch noted that Hinton, the Howells, and the Gardiners were all related by marriage. Hinton, a “tireless crusader for abolition” who promoted the radical journal The Rights of All, was also an agent for the Liberator. He was involved in multiple activist causes including the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society and the Philadelphia Library Company of Colored Persons. He pressed for the restoration of free black suffrage after Pennsylvania took it away in 1838, and he was active in the American Moral Reform Society. Junius Morel, the son of a white slave owner, wrote for and raised funds for abolitionist newspapers and fought African colonization, likening Liberia to “Golgotha” and “a kind of Botany Bay for the United States.” After the passage of the Fugitive Slave Law, he grew even more radical and encouraged African Americans to “defend themselves with force if force was used against them.” Morel’s closest friend was the first black graduate of Wesleyan Academy in Wilbraham, Massachusetts, the Reverend Charles Bennett Ray, publisher and editor of the Colored American, an early New York–based black weekly (fig. 27). Ray was a founding member of the New York City Vigilance Committee.[44]

The convention of 1835 and subsequent antislavery meetings were widely covered in the abolitionist press and closely followed by educated African Americans. Free black elites were a small but extremely well-connected group. If they did not know one another personally, they certainly knew about each other. According to historian Winch, sail maker James Forten, one of Philadelphia’s wealthiest and most influential black abolitionists, “received a constant stream of guests and callers . . . dozens of visitors from all over the United States and Britain, referred . . . by his network of acquaintances.” Such northern networks overlapped whenever possible with others in the South, where many slaves were clearly cognizant of free blacks and whites who might offer assistance with their flight or resettlement. When Harriet Jacobs fled from Edenton, North Carolina, to Philadelphia in 1842, a member of that city’s Vigilance Committee spotted her and took her to a safe house. “She had come to Philadelphia with the names of black folks from Chowan County who had settled in the city and with the knowledge repeatedly condemned by the Edenton Gazette, that the poor slave had many friends in the North.” Evidently, so did Thomas Day.[45]

While Day was in Philadelphia, white North Carolinians convened a state constitutional convention in Raleigh, where voting rights took center stage. In the end, the right to vote was extended to white men who did not own property and taken away from free black men, including property holders like Thomas Day. The vote was close—sixty-six “yeas” and sixty-one “nays”—with Caswell County’s two representatives voting for disenfranchisement and Day’s future benefactor, then Governor Swain, voting to retain free black suffrage. On July 4, the Liberator published a letter that had appeared earlier in the Fayetteville Observer, noting that the state’s two wealthiest free black slave owners, Louis Sheridan and John Carruthers Stanly, had been in a unique and powerful position to protest the loss of their right to vote. The letter stated, “free Negroes such as . . . Sheridan . . . and . . . Stanly . . . should have plead trumpet-tongued in behalf of the more respectable portion of this degraded class.” But there is no evidence that either of them—or Thomas Day—uttered a word of protest. Taking an overt political stand would have been useless and self-destructive.[46]