Newel post attributed to Thomas Day, Littleton Tazewell Hunt House, Milton Township, Caswell County, North Carolina, ca. 1855. (Photo, Tim Buchman.) This is one of twenty-five distinctive S-shaped newels attributed to Day.

Presbyterian Church, Milton, North Carolina, ca. 1837. (Photo, Jerome Bias.)

Detail of the interior of the Presbyterian Church, showing pews made by Thomas Day, Milton, North Carolina, ca. 1837. Walnut with tulip poplar. (Photos, Jerome Bias.) Day joined the church in 1841 but likely made the pews earlier. Rev. Nehemiah Henry Harding served as pastor from 1835 to 1849.

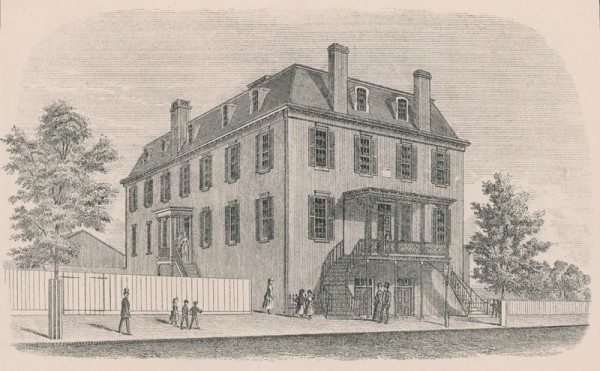

Union Tavern, Milton, North Carolina, ca. 1818. (Photo, Tim Buchman.) Formerly known as the Yellow Tavern, Thomas Day’s home and workshop is on the town’s main street. The tavern was a major stagecoach stop on the route to Petersburg, Virginia.

Newel post attributed to Thomas Day, Woodside, Milton, North Carolina, ca. 1838. (Courtesy, Historic Woodside House; photo, Tim Buchman.) Woodside was built by planter and foundry owner Caleb Hazard Richmond. The house is noted for having interior architectural details fabricated by Thomas Day and for being the site where Confederate general Dodson Ramseur married Richmond’s daughter Mary.

Detail of a newel post attributed to Thomas Day, William Long House, Blanch Community near Milton, North Carolina, ca. 1856. (Photo, Tim Buchman.) This design may have been inspired by Day’s initials.

Detail of a scrolled mirror support on a sideboard attributed to Thomas Day, Milton, North Carolina, 1840–1855. Mahogany and mahogany veneer with yellow pine, tulip poplar, and walnut. (Collection of the North Carolina Museum of History, donation Museum of History Associates and Mr. Thomas S. Erwin; courtesy, Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum; photo, Amy Vaughters.) The sideboard was made for Caleb H. Richmond.

Lounge attributed to Thomas Day, Milton, North Carolina, 1845–1855. Walnut with yellow pine. H. 27 3/8", W. 88 9/16", D. 23 7/16". (Collection of the North Carolina Museum of History, purchase with state funds; photo, North Carolina Museum of History.) Day made twelve documented settees that he referred to as “lounges.” This example descended in the Bass-Engle family.

Sofa attributed to Karsten Petersen, Salem, North Carolina, 1830–1850. Cherry with tulip poplar. H. 25", W. 72", D. 23 1/2". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museum & Gardens.)

Detail of the left term support of a chimneypiece documented to Thomas Day, William Long House, Blanch Community near Milton, North Carolina, ca. 1856. (Photo, Tim Buchman.)

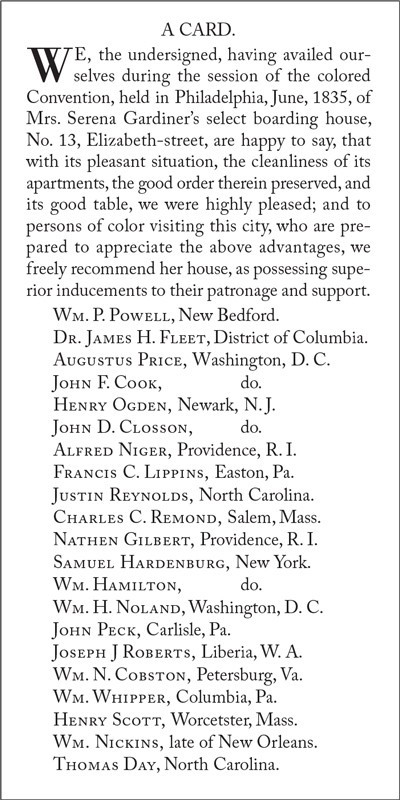

“A Card,” Liberator, August 8, 1835, p. 127. (Facsimile.)

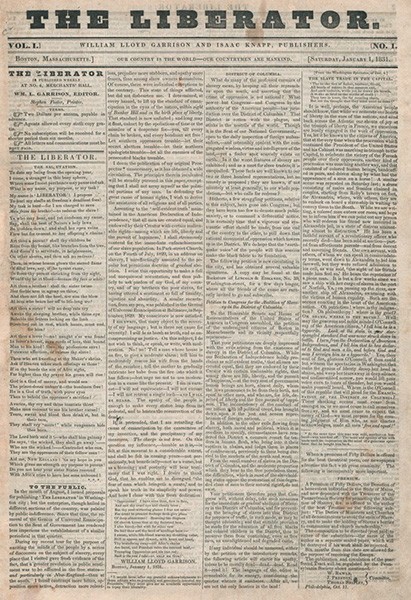

Liberator, January 1, 1831. (Courtesy, Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston, Massachusetts.) The front page of the first edition features William Lloyd Garrison’s famous “Open Letter to the Public,” in which he stated, “I am in earnest—I will not equivocate—I will not excuse—I will not retreat a single inch and I WILL BE HEARD.”

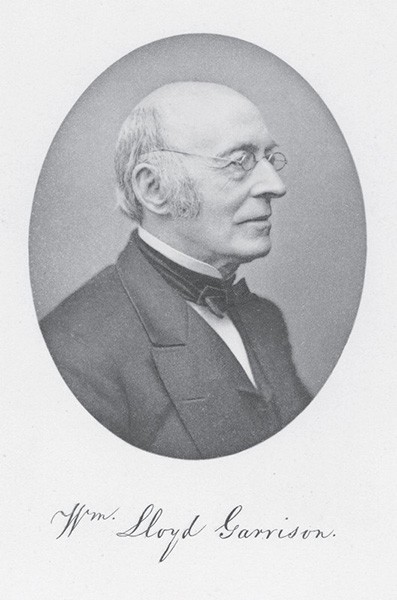

Photograph of William Lloyd Garrison. 3 1/4" x 3". (Courtesy, Prints of American Abolitionists Collection, Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston, Massachusetts.) An uncompromising moralist, Garrison was editor and publisher of the Liberator for more than thirty years and a founder of the American Anti-Slavery Society.

Jeremiah Paul, Manumission of Dinah Nevill, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1795. Oil on canvas. 50" x 39". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This emotionally charged picture depicts Quaker tailor Thomas Harrison purchasing the freedom of “mulatto” slave Dinah Nevill from Benjamin Bannerman, Virginia planter. In 1773 Bannerman bought Nevill and her three children from Nathaniel Lowry of New Jersey and arranged for the family to be transported to Philadelphia. On their arrival in the city, Nevill made a public plea claiming that she and her children were free people. A group of Quakers filed suit to void Bannerman’s claims, but the court ruled in the latter’s favor. This decision and similar cases involving African Americans led to the formation of the Society for the Relief of Negroes Unlawfully Kept in Bondage, which would eventually become the Pennsylvania Abolition Society. Thomas Harrison (1741–1815), who was a founding member of that society, continued the effort to free Nevill and her children, and on May 18, 1779, he manumitted them with money provided by Quaker brewer Samuel Moore.

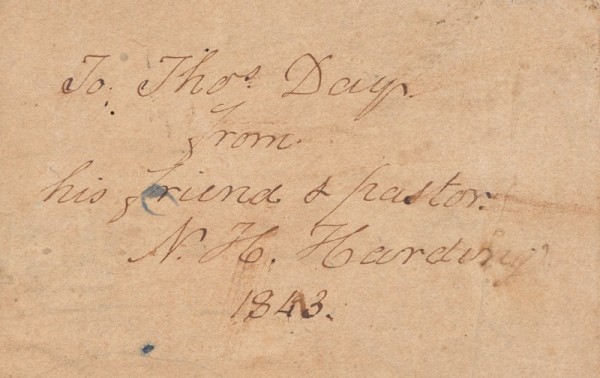

Inscription in Thomas Day’s Bible written by his pastor, Nehemiah Henry Harding. (Collection of Dr. and Mrs. Thomas Baker Day; photo, courtesy, North Carolina Museum of History.)

The Reverend Nehemiah Henry Harding. (Courtesy, Presbyterian Heritage Center, Montreat, North Carolina.)

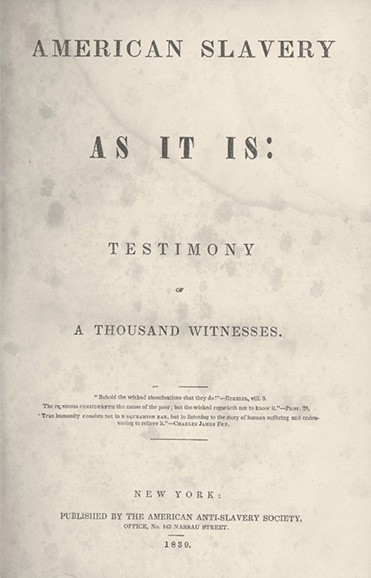

Frontispiece, Theodore Dwight Weld, American Slavery As It Is: Testimony of a Thousand Witnesses, 1839. (Courtesy, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.) This publication is a documentary account of slavery in all its brutality through firsthand testimonials and recollections of former slaves as well as white witnesses. It was distributed widely and is considered one of the most influential antislavery tracts. The Reverend Nehemiah Henry Harding, pastor of the Milton Presbyterian Church and friend of Thomas Day, is represented in the book with a quotation in which he condemns the immorality of slavery as an institution.

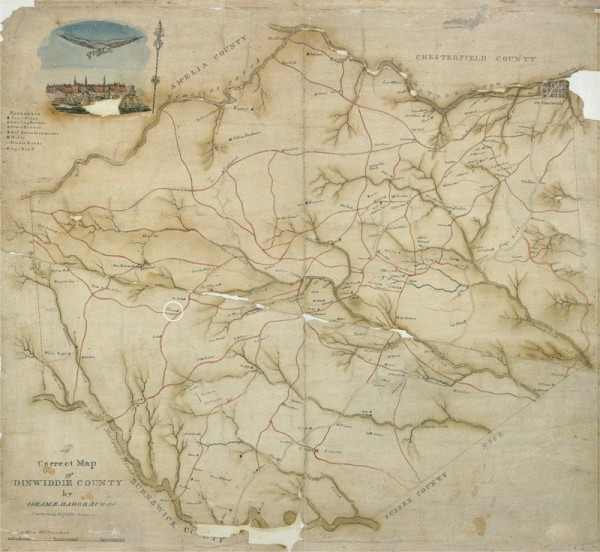

Isham E. Hargrave, “Correct Map of Dinwiddie County, Virginia containing 317,200 acres,” ca. 1820. (Courtesy, Library of Virginia, Richmond, Virginia.) This map shows the “mansion house” of Thomas Day’s maternal grandfather, Dr. Thomas Stewart, on present-day Old White Oak Road. Hargrave was the county’s deputy surveyor.

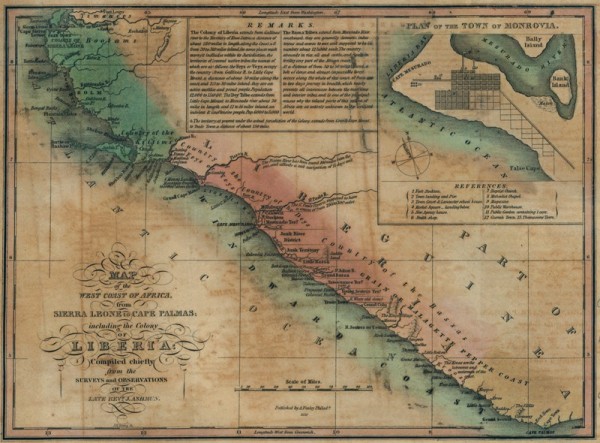

Jehudi Ashmun, “Map of the West Coast of Africa from Sierra Leone to Cape Palmas, including the Colony of Liberia,” printed by A. Finley, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1830. (Courtesy, Geography and Map Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.) Thomas Day’s brother John Day Jr. sailed for Liberia the same year this map was printed. John lived in Monrovia, which is depicted on this map, before embarking on his career as a missionary.

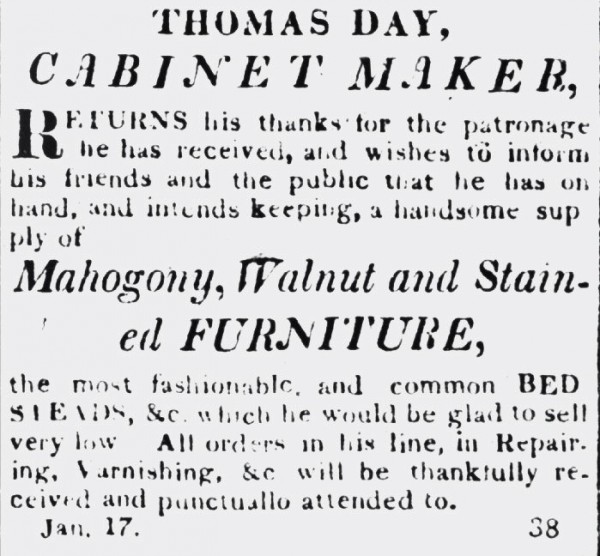

Advertisement for Thomas Day’s shop, Milton Gazette & Roanoke Advertiser, March 1, 1827. (Courtesy, North Carolina Office of Archives and History, Raleigh, North Carolina.)

“Whatnot,” or étagére, attributed to Thomas Day, Milton, North Carolina, 1853–1860. Mahogany and mahogany veneer with yellow pine, tulip poplar, and walnut. H. 69 3/4", W. 40", D. 16". (Private collection; courtesy, Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum; photo, Tim Buchman.) Day made this étagére for Milton merchant John Wilson.

Thomas Day, lady’s open pillar bureau, Milton, North Carolina, 1855. Mahogany and mahogany veneer with yellow pine and tulip poplar. H. 85", W. 42 1/8", D. 20 7/8". (Collection of the North Carolina Museum of History, purchase funds provided by Delta Sigma Theta Sorority, Inc.; Photo, North Carolina Museum of History.) Day made this bureau for former North Carolina governor David S. Reid, who lived in Rockingham County.

Thomas Sully, Joseph Jenkins Roberts (1808–1876), Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1844. Oil on canvas. 33 7/8" x 29 3/8". (Historical Society of Pennsylvania Collection; courtesy, Philadelphia History Museum at the Atwater Kent, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.) Roberts, a Petersburg, Virginia, merchant, was the first president of Liberia and one of the twenty-one men who lodged in Mrs. Gardiner’s Philadelphia boardinghouse during the black abolitionist convention of 1835.

William Whipper, attributed to William Matthew Prior, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1835. Oil on canvas. 24 3/4" x 20 1/8". (Courtesy, Fenimore Art Museum, Cooperstown, New York, gift of Steven C. Clark; photo, Richard Walker.) Whipper was a wealthy Pennsylvania lumber and coal merchant and a founder of the American Moral Reform Society. He delivered the keynote address at the 1835 convention in Philadelphia and signed the “Card,” which places him in the city and the boardinghouse with Thomas Day and John Francis Cook. When a white mob tried to destroy Cook’s school in Washington two months after the convention, he fled to Whipper’s hometown, Columbia, Pennsylvania.

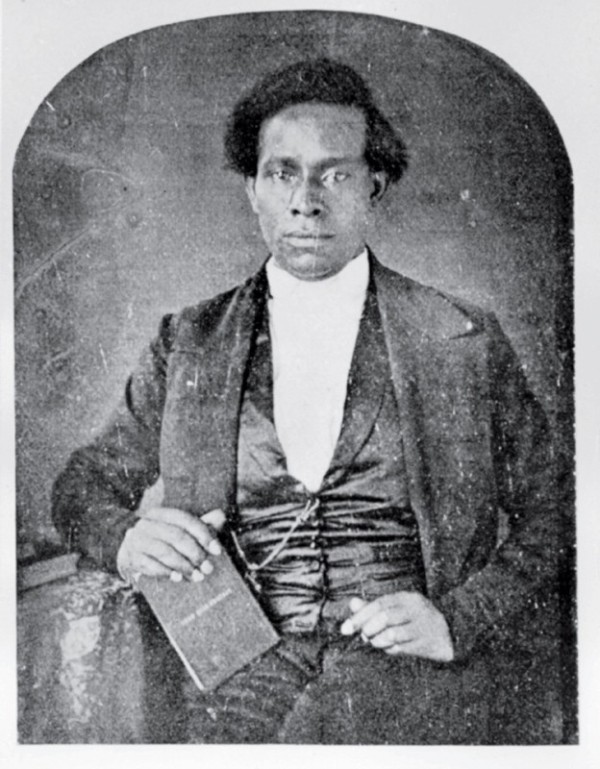

The Reverend John Francis Cook, shown in a copy of a newspaper photograph presented to the Moorland-Spingarn Research Center of Howard University in Washington, D.C. by Cook’s descendants. (Courtesy, Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, Howard University, Washington, D.C.)

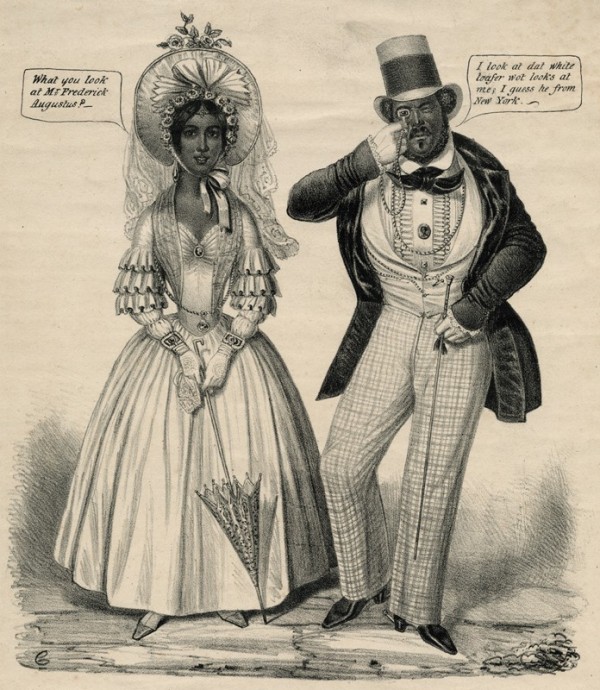

Edward Williams Clay, “Philadelphia Fashions, 1837,” printed and published by H. R. Robinson, New York City, ca. 1837. Lithograph. 18 1/2" x 12 3/4". (Courtesy, The Library Company of Philadelphia.) This image is one of a series of racist cartoons that satirized the dress and manners of Philadelphia’s most affluent African Americans. The male figure is believed to be the well-known barber and social activist Frederick Augustus Hinton and the female, his second wife, Eliza Willson. African American stereotypes such as this were pervasive in mid-nineteenth-century America and reveal that racism was accepted in the North despite the fact that free blacks had more freedoms and greater opportunities there than in the South.

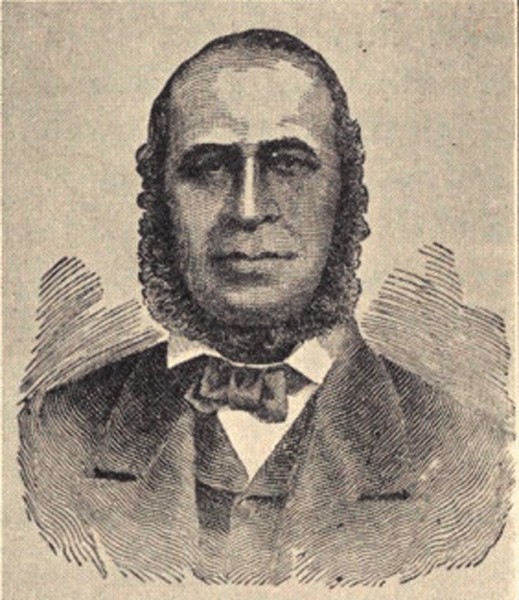

Engraving depicting Charles Bennett Ray, from Carter G. Woodson, The Negro in Our History (Washington, D.C.: Associated Publishers, 1922), p. 146. Ray was a businessman, preacher, and operative with the Underground Railroad. He also served as an agent and later as publisher and editor of the influential black abolitionist newspaper the Colored American, which encouraged the moral, social, and political improvement of African Americans and endorsed a peaceful end to slavery. A native of Falmouth, Massachusetts, he was the first black graduate of Wesleyan Academy in Wilbraham, the same abolitionist-led school where Thomas Day later sent his three children.

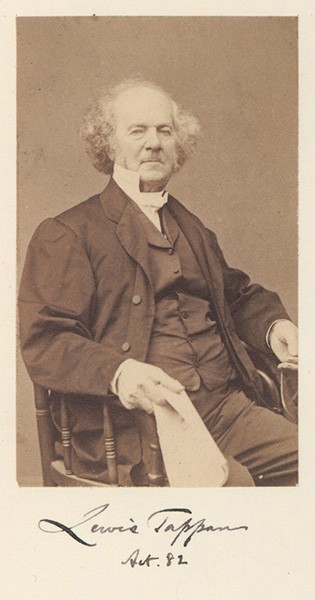

Photograph of Lewis Tappan. 9" x 6" (Courtesy, Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston, Massachusetts, Prints of American Abolitionists Collection.) Tappan, a prominent New York City merchant, and his brother Arthur were among the founders of the American Anti-Slavery Society and their credit-reporting firm was the precursor of Dun & Bradstreet. The diary of the Reverend John Francis Cook of Washington, D.C., reveals that Lewis Tappan was among the many prominent northern abolitionists who corresponded with and visited the minister.

Frontispiece in the Reverend David Sherman, History of the Wesleyan Academy, at Wilbraham, Mass., 1817–1890 (Boston: McDonald & Hill Co., 1893). Thomas Day sent his daughter Mary Ann and younger son, Thomas, to Wesleyan for the 1849–1850 school year. Their brother Devereux joined them there the following term. Thomas Day’s correspondence indicates that he was close to the school’s abolitionist principal, the Reverend Miner Raymond.

Fanny Palmer, “Chatham Square. New York,” for N. Currier. Lithographer, New York City, ca. 1847. Aquatint on paper. Plate, 8" x 12 1/2". (Courtesy, Museum of the City of New York, New York.) W. N. Seymour & Co., the hardware emporium where Thomas Day conducted business for many years, is the white building with the flag in the background.

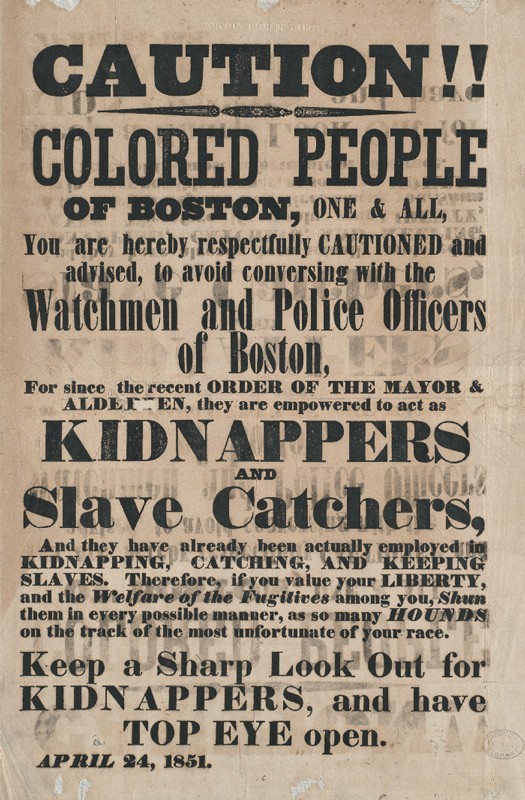

Caution!! Colored People of Boston. Boston, Massachusetts, April 24, 1851. Ink on paper. 16" x 10 1/2". (Courtesy, Trustees of the Boston Public Library/Rare Books Collection.)

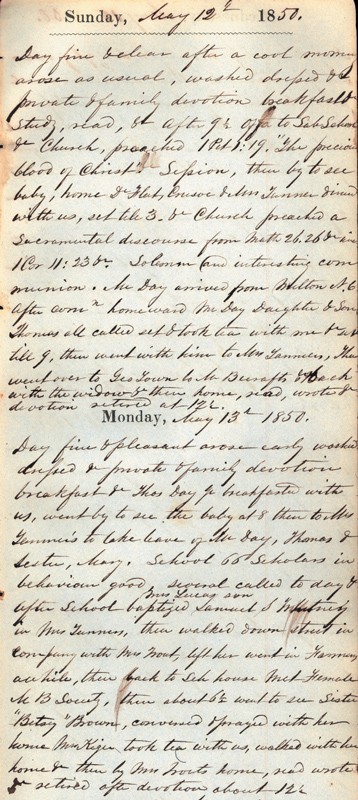

Detail of the Reverend John Francis Cook’s diary entries describing a visit from Thomas Day and two of his children on May 12 and May 13, 1850, box 3, Cook Family Papers, 1827–1869. (Courtesy, Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, Howard University, Washington, D.C.)

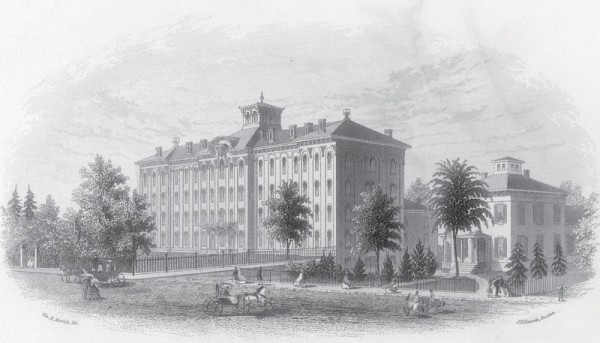

The Stevens School, Washington, D.C., 1870. Copy of an engraving in Annual Report of the Superintendant of Colored Schools of Washington and Georgetown, 1871–2 (Washington, D.C.: National Republican Job Office Print, 1873), frontispiece. (Courtesy, Charles Sumner School Museum and Archives, Washington, D.C.) The District of Columbia’s first public schools for African American children were established in 1867, and the Stevens School, named for radical abolitionist congressman Thaddeus Stevens of Pennsylvania, was built the following year.

Photograph of Annie Day Shepard, ca. 1945. (Archives of North Carolina Central University, Durham, North Carolina.) The granddaughter of Thomas Day, Shepard cofounded North Carolina Central in 1910 with her husband, Dr. James Shepard. She was a college-educated teacher and the namesake of her aunt/stepmother, Annie Washington Day.

Thomas Day, bedstead, Milton, North Carolina, 1853. Mahogany veneer with yellow pine and tulip poplar. H. 87 1/2", L. 82", W. 65 1/2". (Collection of the North Carolina Museum of History, purchase with state funds; photo, North Carolina Museum of History.) Day made this bedstead for Azariah Graves II of Oak Grove plantation in present-day Stony Creek Township, Caswell County, North Carolina.

Passage rack, or hall tree, attributed to Thomas Day, Milton, North Carolina, ca. 1857. Tulip poplar; mahogany graining. H. 86", W. 35", D. 23 1/2". (Courtesy, Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum, gift of Dr. and Mrs. H. W. Moore as part of town renovation of the Ruffin Roulhac House as Hillsborough’s Town Hall; photo, Amy Vaughters.) The rack was made for C. H. Moseley of Caswell County, North Carolina.

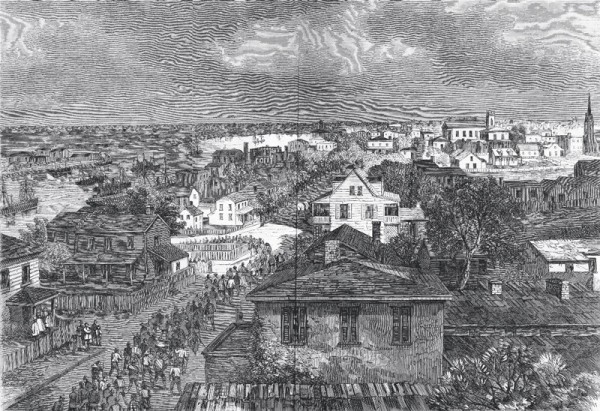

“View of Wilmington with Released Prisoners Marching on Their Way to the Transports, Feb. 27, 1865,” Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, April 1, 1865. (North Carolina Civil War Image Portfolio, Prints and Photographs, North Carolina Collection, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.) The focus of this image is freed Union prisoners of war, Confederate captives, and refugees. The Days were in Wilmington when this image was created.