This photograph shows several workmen standing in front of a machine used to press clay slabs into terra-cotta bombs, ca. 1918. Note the finished bombs on the table in the front center of the photograph and the extruded clay slabs stacked on the oor in the front right of the photograph. (Courtesy, Middlesex County Cultural and Heritage Commission.)

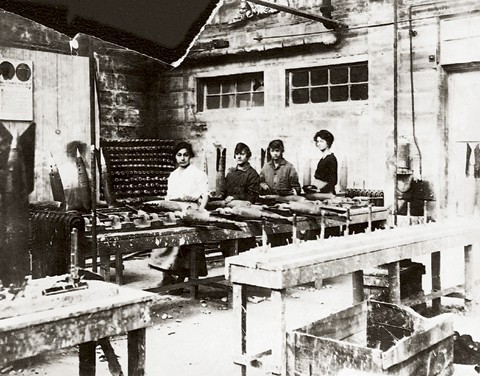

Women affixing fins to terra cotta dummy bombs on an assembly line at an unidentified New Jersey site, ca. 1918. (Courtesy, Middlesex County Cultural and Heritage Commission, Stephen Kermondy Donation.)

Workmen loading pallets of terra cotta practice bombs at the Atlantic Terra Cotta Company’s Plant #1, Staten Island, New York, ca. 1918. (Courtesy, Staten Island Historical Society.)

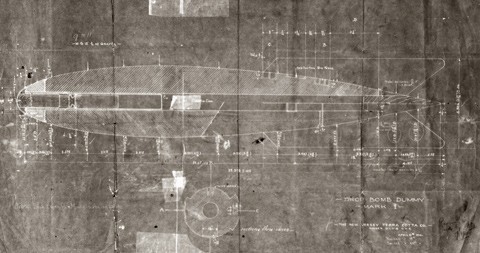

A blueprint for the manufacture of the “Drop Bomb Dummy, Mark 1” from the New Jersey Terra Cotta Company, dated April 11, 1918. (Courtesy, Susan Tunick.)

The stacked terra cotta practice bombs as found in the field. (Photo, Mark Nonestied.)

A sample of the 124 bombs recovered by the Middlesex County Cultural and Heritage Commission. (Photo, Mark Nonestied.) Note the unexcavated samples in the upper left corner of the photograph.

An intact terra cotta practice bomb. L. 25 3/4". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Notice the coarse texture of the clay body. Apparently the bombs were hastily and rather sloppily manufactured.

Upright view of bomb illustrated in figure 7.

The Cornelius Low House/Middlesex County Museum, a project of the Middlesex County Cultural and Heritage Commission, researches and mounts exhibits pertinent to New Jersey history. Recently, while preparing for an upcoming exhibit titled “UnCommon Clay: New Jersey’s Architectural Terra Cotta Industry,” museum staff members Mark Nonestied, Hillary Murtha, and Guest Curator Richard Veit visited the sites of half a dozen terra cotta manufacturers in Middlesex County, New Jersey. These factories were active between the 1870s and 1960s, at a time when New Jersey led the nation in the production of architectural terra cotta. Through the cooperation of the property owners, access was gained to many sites that had previously been off limits to researchers. During a site visit in the fall of 2001 to the former Federal Seaboard Terra Cotta Corporation in Woodbridge Township, New Jersey, a large cache of terra cotta practice bombs was discovered. Although historians and archaeologists were aware that terra cotta practice bombs had been produced during the First World War, until this discovery it was thought that they had all been used and hence lost.

Architectural terra cotta is a versatile medium, which can be molded, sculpted, and glazed to imitate all sorts of materials. Turn of the century architects saw it as a superior building material that was long lasting, impervious to the elements, easily glazed, lighter and cheaper than stone.[1] Most of the architectural terra cotta produced in New Jersey’s clay district was used as ornamental cladding on the first skyscrapers. In addition to architectural pieces, terra cotta workers made a variety of other items. These included colorful grave markers, hitching posts, carriage blocks, chimney pots, and statuary.[2] With good reason, terra cotta was known as the great imitator.

Perhaps the most unusual use of terra cotta was in the form of dummy or practice bombs. These were made and used during the First World War. With the United States’ entry into World War I in April of 1917, there was a shift from the production of domestic goods to the manufacture of war-related materials. Responding to the shortage of architectural work and the need for military supplies, several terra cotta manufacturers, at the request of the United States Army Air Corps, began manufacturing terra cotta bombs. According to historian William McGinnis:

Harry M. Gerns (of Federal Terra Cotta) was sent to Washington on request of the War Department. Major Burgardees asked whether practice bombs weighing about twenty pounds could be made. They were made at the Amboy plant from drawings furnished by the Major. An order was immediately placed for 500,000.[3]

At least four firms manufactured the practice bombs. They included two New Jersey firms, Federal Terra Cotta of Woodbridge and New Jersey Terra Cotta of Perth Amboy, as well as the Atlantic Terra Cotta Company of Staten Island, and the American Terra Cotta Company of Illinois. The cache of bombs was found at the Federal Terra Cotta Company’s Woodbridge factory. Historic photographs from that factory and others show the manufacturing process, including pressing the clay, assembling the bombs, and stacking them on pallets for shipment (figs. 1-3). A blueprint dated April 11, 1918, from the New Jersey Terra Cotta Company also depicts a bomb like those recovered in Woodbridge (fig. 4).

During a recent interview, centenarian William R. Crooks, the United States’ oldest living military pilot, recalled using terra cotta practice bombs in ight school. Crooks, a World War I veteran, learned to y in 1918. He stated that each of the planes carried four terra cotta practice bombs under their wings. The bombs were armed with shotgun shell firing mechanisms.[4] Susan Tunick, author of Terra-Cotta Skyline, cites George A. Berry III, the last owner of the American Terra Cotta Company, who “explained that these hollow-clay practice bombs . . . were filled with our or powdered plaster, whichever was available. The spot where the bomb ‘exploded’ would thus be covered with a white powder which was easily visible and helped to assess the accuracy of each drop.”[5]

With the end of the war the market for terra cotta practice bombs dried up. The factories went back to manufacturing architectural elements. Upwards of a thousand stacked dummy bombs were abandoned next to a railroad siding at the Federal Seaboard factory. In 1941 the plant closed and a cardboard box manufacturer took over the factory. Overgrown with weeds, the bombs lay forgotten until their recent rediscovery.

During a site visit in October of 2001, museum staff along with members of the Woodbridge Historical Association toured the factory grounds. Along with architectural terra cotta, several strange conical terra cotta fragments were noted in a recently graded portion of the property (fig. 5). Hurried excavation revealed that these items were in fact the bodies of dummy bombs (fig. 6). Further investigation quickly revealed that upward of a thousand were located near a former rail line that serviced the factory. The bombs, stacked in courses of about eight feet high, made up a small embankment leading up to a former loading platform. The embankment measured about 150 feet in length, and one section also contained architectural terra cotta fragments. As the site is slated for redevelopment, the Woodbridge Historical Association with the Middlesex County Cultural and Heritage Commission carried out a systematic recovery of 124 bombs.

The practice bombs were made from coarse red terra cotta and appear to have been manufactured in two-piece molds as they show a seam running lengthwise up their sides. They measure twenty-five and three-fourths inches long, and five inches in diameter (figs. 7, 8). Each bomb weighs eighteen pounds. The bombs’ tails were notched and grooved to accept fins. These unusual ceramic artifacts attest to the versatility of terra cotta, and also serve as grim reminders of the first use of aerial bombing during World War I.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was made possible by the Middlesex County Cultural and Heritage Commission, a department of County Government, and the Middlesex County Board of Chosen Freeholders.

Richard Veit, Ph. D.

Director, Monmouth University Center for New Jersey History Department of History and Anthropology, Monmouth University

West Long Branch, N.J.

Mark Nonestied

Assistant Curator, Middlesex County Museum

Middlesex County Cultural and Heritage Commission

New Brunswick, N.J.

Richard F. Veit, “Moving Beyond the Factory Gates: The Industrial Archaeology of New Jersey’s Terra Cotta Industry,” IA: The Journal of the Society for Industrial Archaeology 22, no. 2 (1999): 5–28.

Ibid., p. 19.

William C. McGinnis, History of Perth Amboy, New Jersey 1651–1962 (Perth Amboy, N.J.: American Publishing Company, 1962), p. 11. McGinnis erroneously notes the company as Seaboard. In fact, it was Federal Terra Cotta, which merged with the South Amboy Terra Cotta Company and New Jersey Terra Cotta Company in 1928 to form Federal Seaboard Terra Cotta.

(http: www.af.mil/news/Oct2001/n200)

Susan Tunick, Terra-Cotta Skyline (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton Architectural Press, 1997), p. 113.