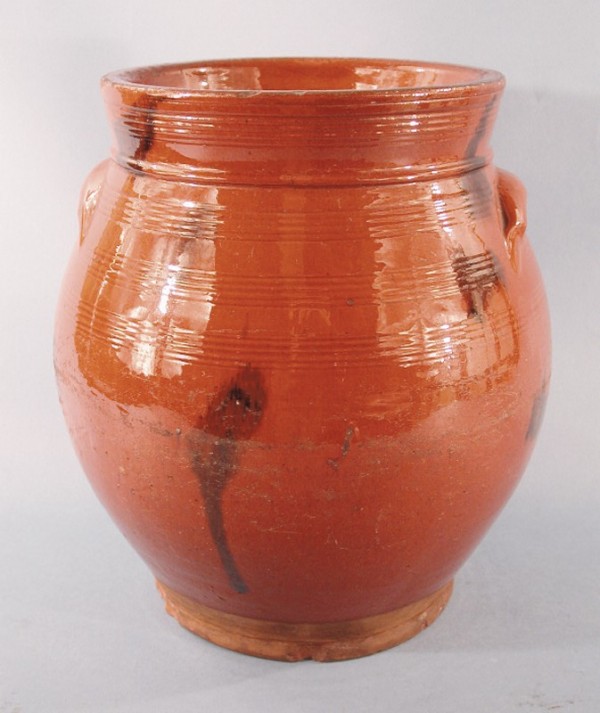

Jar, attributed to Day’s Pottery, Norwalk, Connecticut, 1800–1825. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 11 1/4". (Courtesy, Connecticut Historical Society.)

Bowl, Iran, Nishapur, tenth century. Slip-decorated earthenware. D. 18". Inscribed on obverse, in Arabic: “Planning before work protects you from regret; prosperity and peace.” (Courtesy, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 65.106.2.)

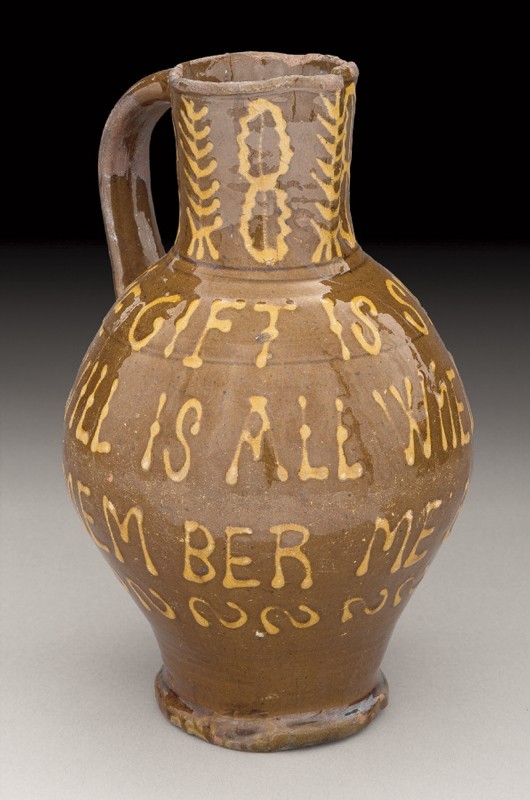

Jug, maker unidentified, Harlow, Essex, England, 1650–1700. Slip-decorated earthenware. H. 6 3/8". Inscribed along sides: “THE GIFT IS SMALL GOO / D WILL IS ALL WHEN THES YOU SE / E REMEMBER ME BE MERY AND / WIES” (Courtesy, The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

Milk pan, Hervey Brooks (1779–1873), Goshen, Connecticut, 1858. Slip-decorated earthenware. D. 13". Inscribed on obverse: “HB / 1858” (Courtesy, Litchfield Historical Society.)

Dish, maker unidentified, probably Pennsylvania, ca. 1835. Slip-decorated earthenware. D. 13 1/2". Inscribed on obverse: “Temperance / Health / Wealth” (Courtesy, Historic New England.)

Dish, maker unidentified, probably Pennsylvania, ca. 1835. Slip-decorated earthenware. D. 14". Inscribed on obverse: “Remember / him that is / in bonds” (Courtesy, Sotheby’s.)

Dish, attributed to George Wolfkiel (1805–1867), Bergen County, New Jersey, 1847–1867. Slip-decorated earthenware. D. 12 7/8". Inscribed on obverse: “Mandy” (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum, Garden and Library.)

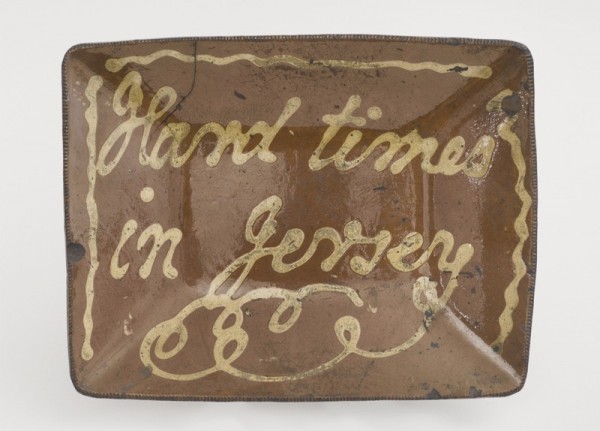

Dish, possibly George Wolfkiel (1805–1867), Bergen County, New Jersey, ca. 1837. Slip-decorated earthenware. 12 1/4" x 15 5/8". Inscribed on obverse: “Hard times / in Jersey” (Courtesy, Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Gift of Mrs. Albert Hastings Pitkin in memory of her husband, 1918.1198.)

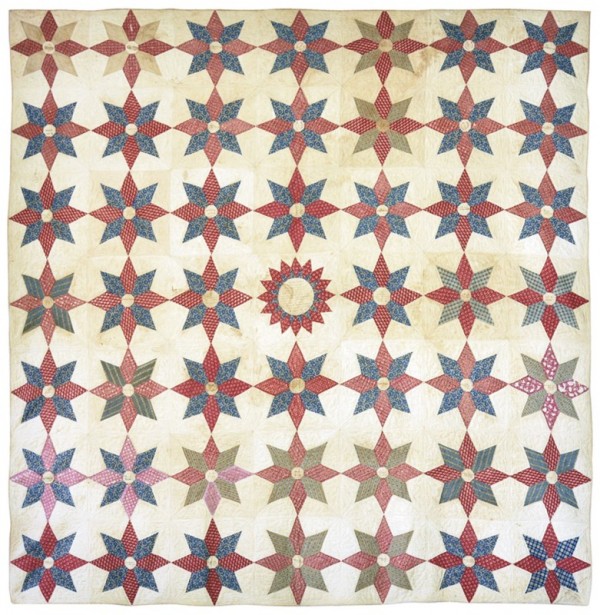

Friendship” quilt, several makers, Norwalk, Connecticut, ca. 1847. Various printed cottons. 80" x 83". (Courtesy, Stamford History Center.)

Dish, attributed to Smith Pottery, Norwalk, Connecticut, ca. 1844. Slip-decorated earthenware. L. 16". Inscribed on obverse: “Finetta Wheeler” (Courtesy, Norwalk–Village Green Chapter, Daughters of the American Revolution.)

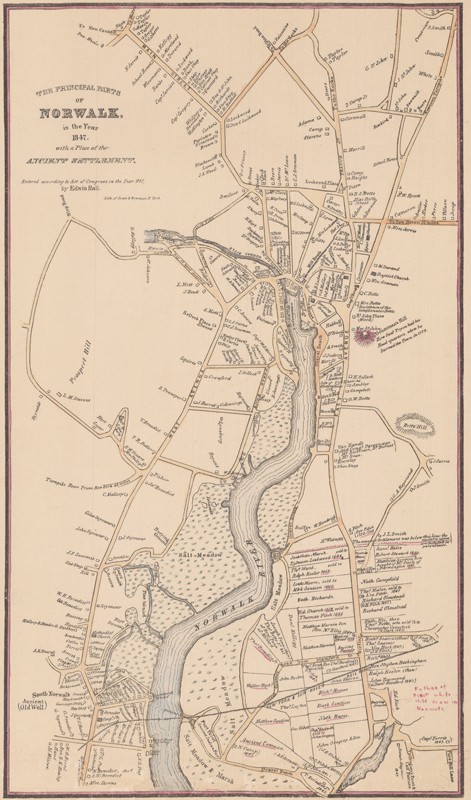

Map detail, The Principal Parts of Norwalk in the Year 1847, by Edwin Hall, printed by Jones & Newman, New York, New York, 1847–1849. Lithograph. Overall 17 7/8" x 11". (Courtesy, Connecticut Historical Society.)

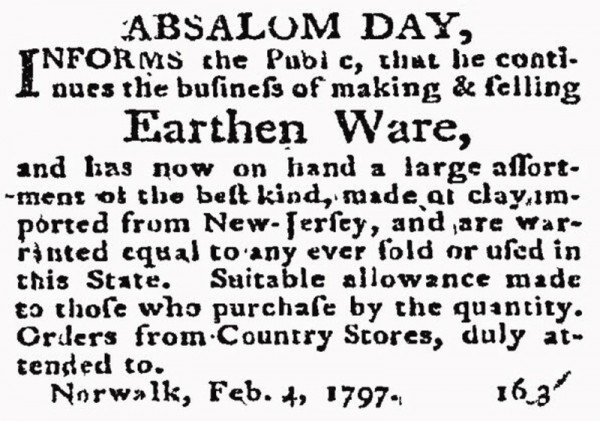

Announcement by Absalom Day dated February 4, 1797, published in the Republican Journal (Danbury, Conn.), February 4, 1797.

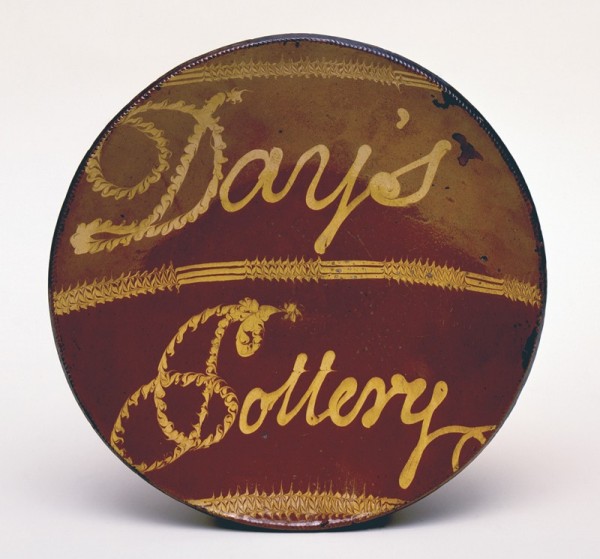

Dish, attributed to Absalom Day (1770–1843), Norwalk, Connecticut, ca. 1796. Slip-decorated earthenware. D. 15 1/2". Inscribed on obverse: “Day’s / Pottery” (Courtesy, High Museum of Art.)

Dish, attributed to Absalom Day (1770–1843), Norwalk, Connecticut, 1794–1800. Slip-decorated earthenware. W. 16 1/2". Inscribed on obverse: “AD” (conjoined initials). (Courtesy, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Mrs. Robert W. de Forest, 1933, 34.100.42.)

Dish, maker unidentified, Huntington, New York, probably 1851. Slip-decorated earthenware. D. 12 3/4". Inscribed on obverse with double-quill slip cup: “America” (Courtesy, Historic New England.) The inscription refers to the yacht America, which won the Royal Yacht Squadron’s 100-Pound Cup sailing race around the Isle of Wight in 1851. Thereafter the race has been known as the America’s Cup.

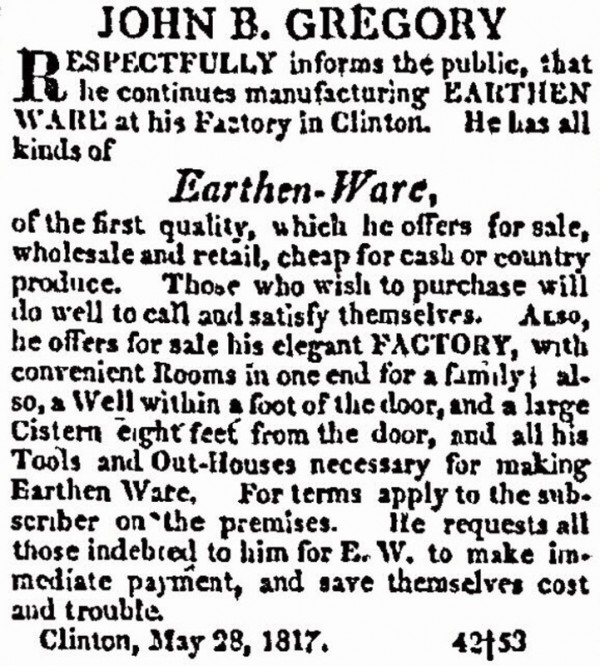

Announcement by John B. Gregory dated May 28, 1817, published in the Columbian Gazette (Utica, N.Y.), June 3, 1817.

Dish, John Betts Gregory (1782–1842), Clinton, New York, 1823. Slip-decorated earthenware. D. 15 5/8". Inscribed on obverse: “Made / By JBG / Oct 18 1823 / Clinton” (Courtesy, Clinton Historical Society.)

Dish, John Betts Gregory (1782–1842), Clinton, New York, 1824. Slip-decorated earthenware. D. 10 1/2". Inscribed on obverse: “Harriet / Ostrander / Dish made by / John B Gregory / Clinton / 1824” (Courtesy, Crocker Farm.)

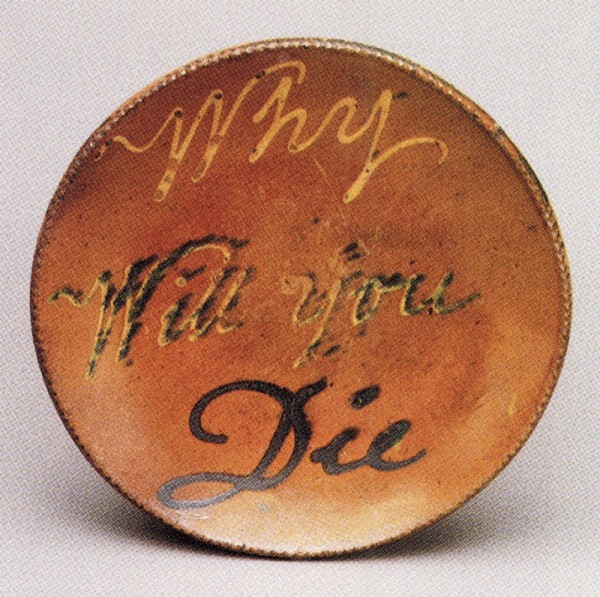

Dish, attributed to John Betts Gregory (1782–1842), Clinton, New York, 1823–1831. Slip-decorated earthenware. D. 11 3/4". Inscribed on obverse: “Why / Will you / Die” (Courtesy, George R. Hamell.)

Dish, attributed to Day’s Pottery or Smith Pottery, Norwalk, Connecticut, ca. 1824. Slip-decorated earthenware. D. 12 1/4". Inscribed on obverse: “Lafayette” (Courtesy, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Mrs. Robert W. de Forest, 1933, 34.100.223.)

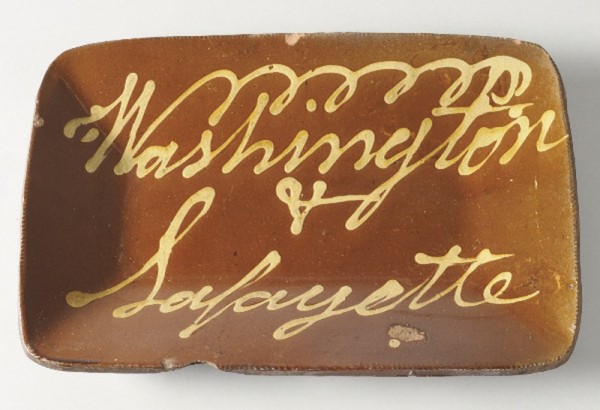

Dish, attributed to Day’s Pottery or Smith Pottery, Norwalk, Connecticut, ca. 1824. Slip-decorated earthenware. D. 15 1/2". Inscribed on obverse: “Washington / & / Lafayette” (Courtesy, Lewis Scranton.)

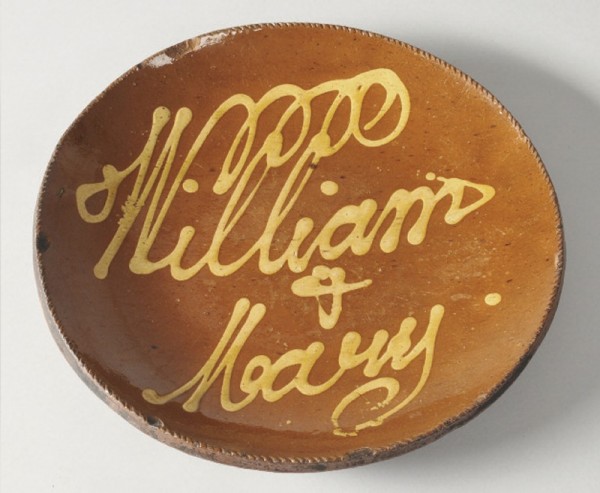

Dish, attributed to the Smith Pottery, Norwalk, Connecticut, 1825–1830. Slip-decorated earthenware. D. 11 1/8". Inscribed on obverse: “William / & / Mary” (Photo, Skinner, Inc.)

Dish, attributed to the Smith Pottery, Norwalk, Connecticut, 1825–1850. Slip-decorated earthenware. W. 11 3/4". Inscribed on obverse: “Nancys / Dish” (Courtesy, Yale University Art Gallery, 1931.1788.)

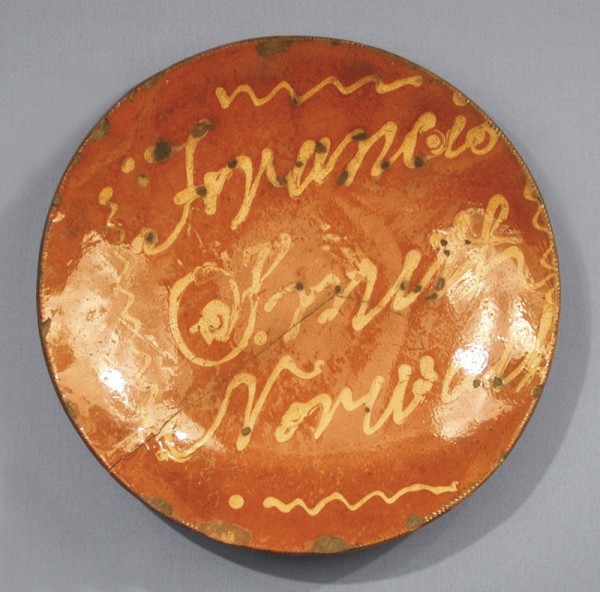

Dish, attributed to the Smith Pottery, Norwalk, Connecticut, 1825–1850. Slip-decorated earthenware. D. 14 1/4". Inscribed on obverse: “Francis / Smith / Norwalk” (Courtesy, The Connecticut Historical Society, 1961.26.1.)

Dish, attributed to the Smith Pottery, Norwalk, Connecticut, 1825–1850. Slip-decorated earthenware. D. 8". Inscribed on obverse: “Elsey” (Courtesy, Pook & Pook, Inc.)

Dish, attributed to the Smith Pottery, Norwalk, Connecticut, 1825–1850. Slip-decorated earthenware. D. 10". Inscribed on obverse: “Clam / Potpie” (Courtesy, The Connecticut Historical Society.)

Dish, attributed to the Smith Pottery, Norwalk, Connecticut, 1825–1850. Slip-decorated earthenware. D. 13". Inscribed on obverse: “Plumb / Pudding” (Courtesy, The Connecticut Historical Society.)

Dish, attributed to the Smith Pottery, Norwalk, Connecticut, 1825–1850. Slip-decorated earthenware. D. 14 1/2". Inscribed on obverse: “forgive / all injuries” (Courtesy, Historic New England.)

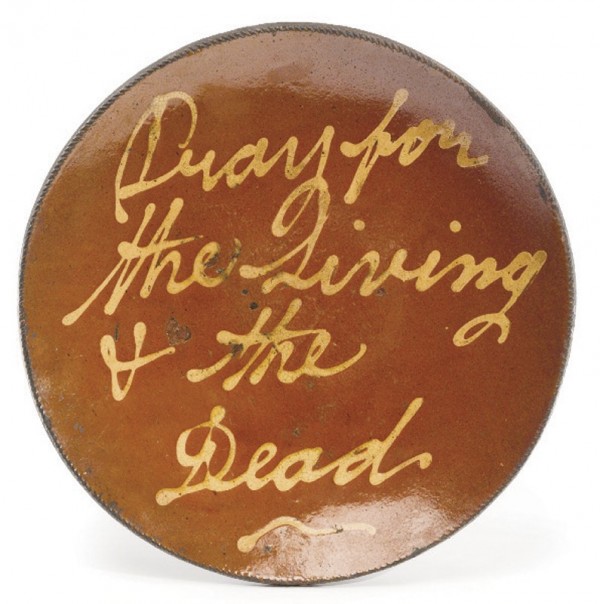

Dish, attributed to the Smith Pottery, Norwalk, Connecticut, 1825–1850. Slip-decorated earthenware. D. 14 1/2". Inscribed on obverse: “Pray for / the Living / & the / Dead” (Courtesy, Sotheby’s.)

Dish, attributed to the Smith Pottery, Norwalk, Connecticut, 1825–1850. Slip-decorated earthenware. D. 12". Inscribed on obverse: “Honour / the / humane” (Courtesy, The Art Institute of Chicago, Gift of Mrs. John Worthy, 1918.284.)

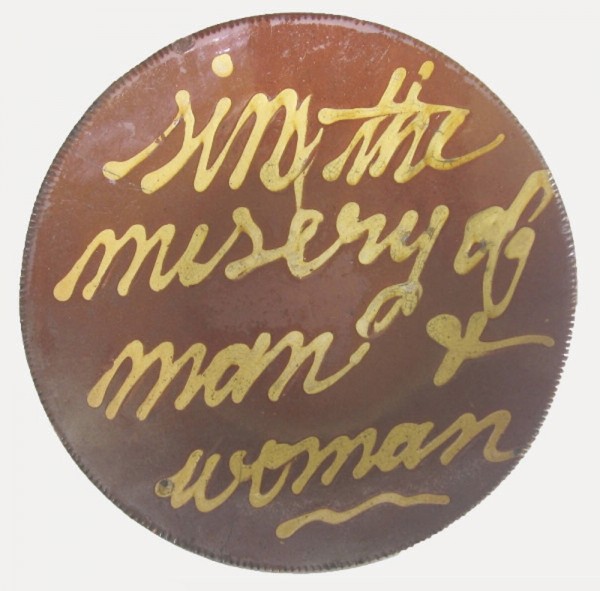

Dish, attributed to the Smith Pottery, Norwalk, Connecticut, 1825–1850. Slip-decorated earthenware. D. 10". Inscribed on obverse: “sin the / misery of / man & / woman” (Courtesy, Sam Herrup.)

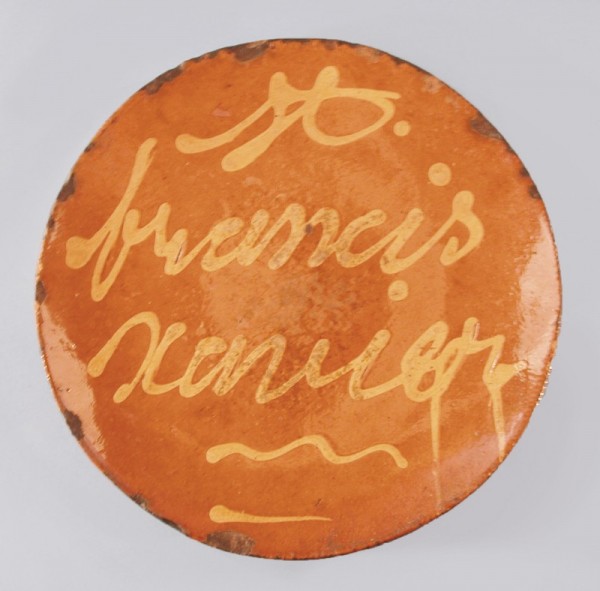

Dish, attributed to the Smith Pottery, Norwalk, Connecticut, 1825–1850. Slip-decorated earthenware. D. 11". Inscribed on obverse: “st. / francis / xavier” (Courtesy, The Connecticut Historical Society, 1945.1.1368.)

Dish, attributed to the Smith Pottery, Norwalk, Connecticut, 1825–1850. Slip-decorated earthenware. D. 11". Inscribed on obverse: “st / Remigius” (Courtesy, The Connecticut Historical Society, 1945.1.1369.)

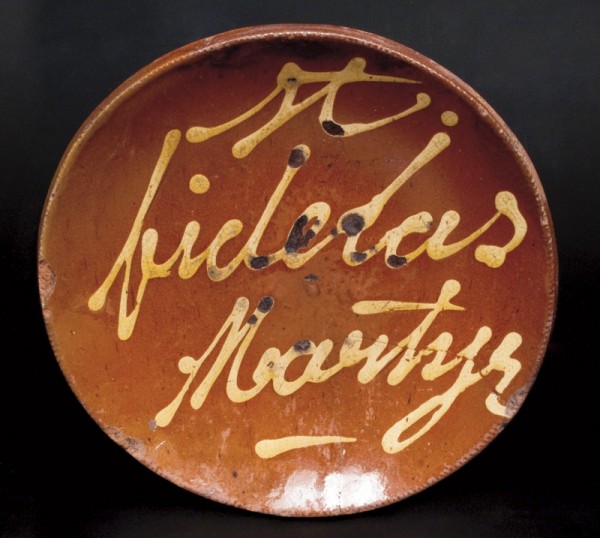

Dish, attributed to the Smith Pottery, Norwalk, Connecticut, 1825–1850. Slip-decorated earthenware. D. 10 1/4". Inscribed on obverse: “st. / fidelas / Martyr” (Sold at Crocker Farm, March 14, 2015, lot 113.)

Dish, attributed to John Betts Gregory (1782–1842), probably Norwalk, Connecticut, 1832–1840. Slip-decorated earthenware. L. 16 5/16". Inscribed on obverse: “Ware / plenty Come / and buy” (Courtesy, The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

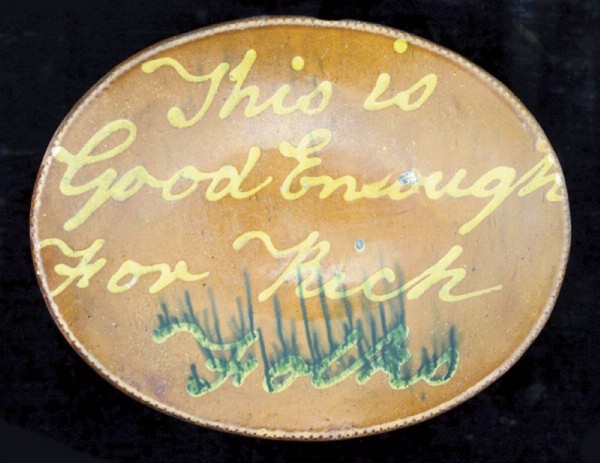

Dish, attributed to John Betts Gregory (1782–1842), probably Norwalk, Connecticut, 1832–1840. Slip-decorated earthenware. L. 14 1/4". Inscribed on obverse: “This is / Good Enough / For Rich / Folks” (Courtesy, Nancy and Gary Stass.)

Dish, attributed to the Smith Pottery, Norwalk, Connecticut, 1825–1850. Slip-decorated earthenware. D. 13 1/4". Inscribed on obverse: “Break / Away / more / making” (Courtesy, Pook & Pook, Inc.)

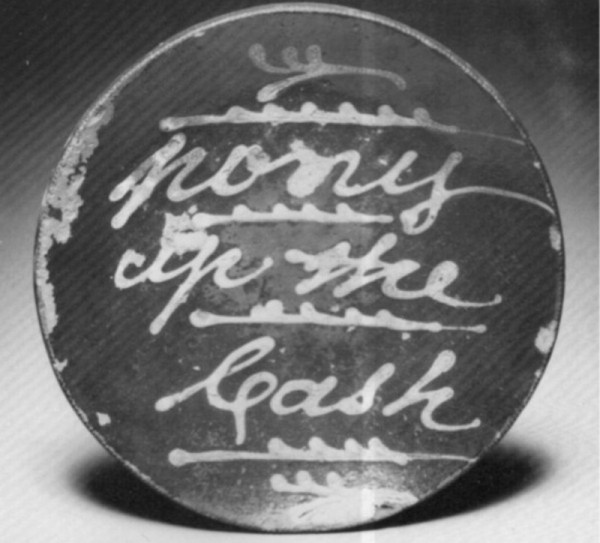

Dish, attributed to the Smith Pottery, Norwalk, Connecticut, 1825–1850. Slip-decorated earthenware. D. 10 1/2". Inscribed on obverse: “pony / up the / Cash” (Courtesy, Lewis Scranton.)

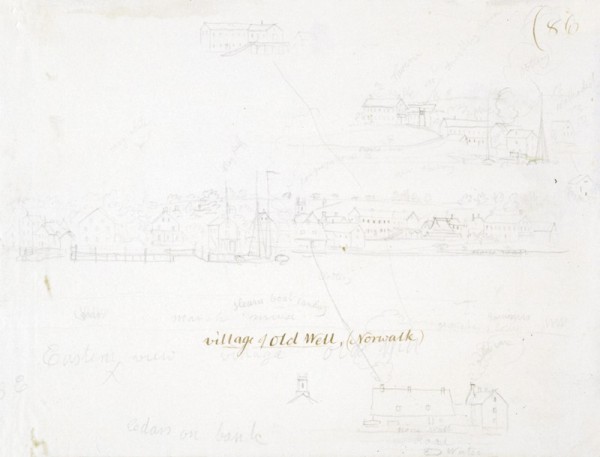

Village of Old Well, John Warner Barber (1798–1885), Norwalk, Connecticut, 1836. Graphite on paper. 7 1/2" x 9 7/8". (Courtesy, Connecticut Historical Society, 1953.5.212.)

Dish, attributed to the Smith Pottery, Norwalk, Connecticut, 1825–1850. Slip-decorated earthenware. D. 13". Inscribed on obverse: “Newyork / City” (Courtesy, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Katharine Prentis Murphy, 1948, 48.124.)

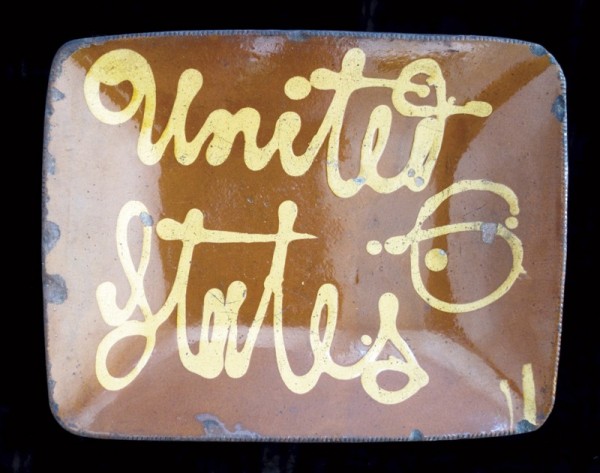

Dish, attributed to the Smith Pottery, Norwalk, Connecticut, 1825–1850. Slip-decorated earthenware. L. 12 1/4". Inscribed on obverse: “United / States” (Courtesy, Nancy and Gary Stass.)

Dish, attributed to the Smith Pottery, Norwalk, Connecticut, probably 1852. Slip-decorated earthenware. D. 13". Inscribed on obverse: “Kossuth / 1852” (Courtesy, Historic New England; Beauport, Sleeper-McCann House.)

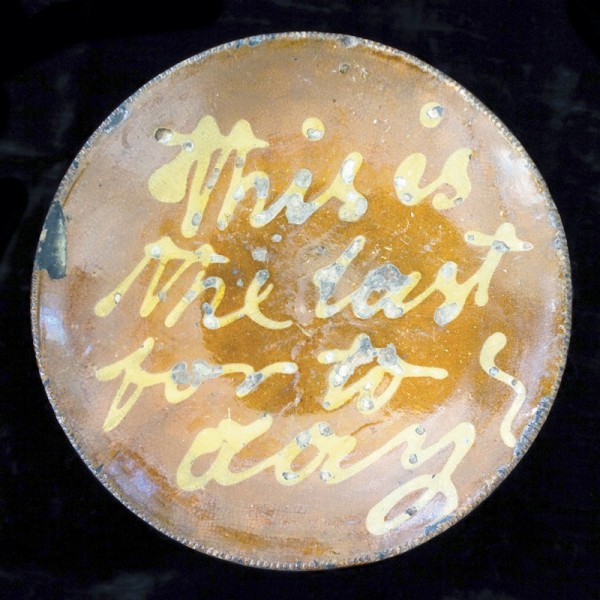

Dish, attributed to the Smith Pottery, Norwalk, Connecticut, 1825–1850. Slip-decorated earthenware. D. 12". Inscribed on obverse: “This is / the last / for to / day” (Courtesy, Nancy and Gary Stass.)

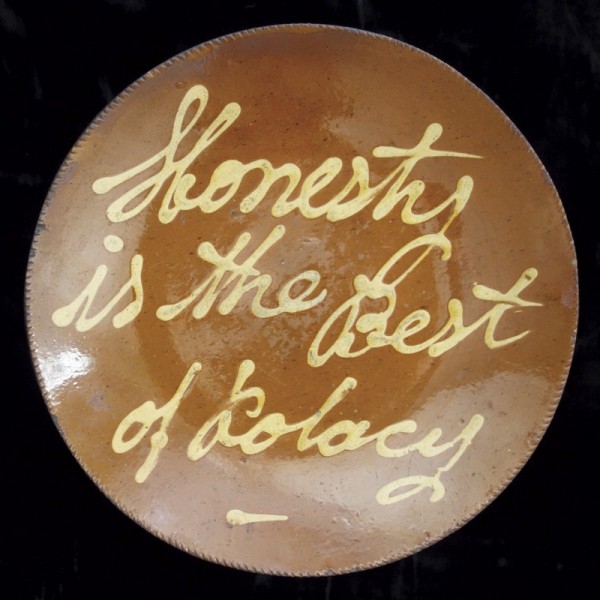

Dish, attributed to the Smith Pottery, Norwalk, Conneticut, 1825–1850. Slip-decorated earthenware. D. 12 1/4". Inscribed on obverse: “Honesty / is the Best / of polacy” (Courtesy, Nancy and Gary Stass.)

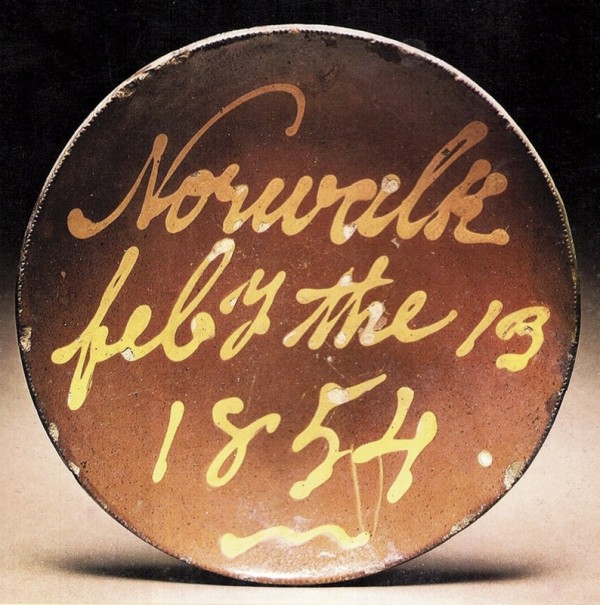

Dish, attributed to the Smith Pottery, Norwalk, Connecticut, 1825–1850. Slip-decorated earthenware. D. 18". Inscribed on obverse: “Norwalk / feby the 13 / 1854” (Courtesy, Norwalk Historical Society.)

In September 1953 auctioneer King Brown of Wilton, Connecticut, sold the collection of antiques formed by Andrew L. Winton (1864–1946) and his wife, Kate Barber Winton (1882–1974), at their home in Wilton. The Wintons were both respected food scientists—Andrew once headed the Chicago Food and Drug Inspection Laboratory, and Kate had been a microscopist at the Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station—and they had collaborated on books and articles on food science beginning in 1907. Seven years after Andrew died, Kate sold their collection “Consisting mostly of furniture etc. of New England origin, the majority of which is from Fairfield County”; included in the sale was a “collection of Norwalk slipware and pottery.”[1]

The Wintons had researched Norwalk’s pottery industry and summarized their findings in an article that was published in 1934.[2] Bringing their scientific training to the project, they established the extent of Norwalk pottery manufacturing beginning in the eighteenth century, uncovered the names of several of the town’s early potters, and located descendants who retained pottery that was attributed to their forebears. The couple also investigated the sites of early potteries that had disappeared long before but evidence of whose existence remained underground. On one outing, “equipped with a potato hook and weeder,” they excavated the site of a pottery they identified as having belonged to Asa Hoyt Sr. (1744–1806) and found “hundreds of fragments of pottery, furnishing indubitable evidence as to the wares of the pottery.”[3]

Among the examples of Norwalk pottery illustrated in the Wintons’ article were three dishes having slip inscriptions reading, respectively, “Susan,” “Adaline,” and “pony up the Cash.”[4] No fragments of this slip-script pottery, whose decoration was very different from the concentric-circle-and-line decoration that they had uncovered elsewhere in Norwalk, were found. In the eighty years since the Wintons’ article was published, Norwalk has emerged as an important center for the production of earthenware and stoneware pottery, and many examples with slip inscriptions have been located. Evidence suggests that slip-script earthenware dishes began as souvenir ware made at the pottery operated by Absalom Day about 1824. Production soon expanded under the direction of Day’s nephew, Asa E. Smith (1798–1880), and a variety of personal, secular, and religious inscriptions were written on dishes over the next thirty years. This pottery offers important information about the town’s residents and their everyday life that is often omitted from the written record.

Pottery forms can yield information about production technologies, both local and regional preferences, foodways, the economics of the pottery industry, and cultural traditions. Those factors, along with function, determined form, and the form was paramount in successfully satisfying the purpose for which an object was intended. Decoration contributes nothing to the usefulness of pottery; identical forms, one decorated and the other plain, perform equally well. For Norwalk slip-script earthenware, however, functionality was secondary to decoration. Some dishes were used for preparing and serving food, but many show little evidence of use, indicating that the ornamental and commemorative value of the ware was primary. Many of the inscriptions document the names of original owners of the pieces, the foods they ate, the religious figures they revered, their heroes, and the biblical texts and everyday expressions that were meaningful to them.

In 1918 Albert Hastings Pitkin wrote: “Hartford seems to have been the center for the manufacture of Hollow Ware such as jugs, crocks, pitchers, etc.—So, from Norwalk came the heavy pie dishes, decorated with wavy lines of cream-colored slip, or with the owner’s name.”[5] Hollow ware was, in fact, an important component of Norwalk’s pottery production, in addition to the dishes Pitkin identified. Settled in the seventeenth century, Norwalk developed along the Norwalk River, where it empties into Long Island Sound. The town’s location made it well suited as a potting center. The sound was a major transportation thoroughfare linking Norwalk with other coastal Connecticut towns, Long Island, and New York City—all markets for the town’s pottery. An “old potter’s shop” probably owned by Asa Hoyt Sr. was in operation when British general William Tryon burned 130 Norwalk houses and numerous businesses in 1779, during the Revolutionary War.[6] After the war, potteries were reestablished: five were in operation at different times between 1825 and 1835, producing earthenware and stoneware, ceramic doorknobs, drawer pulls, and buttons. Several hollow ware forms splotched with manganese glaze are associated with both Norwalk and Huntington, Long Island, showing the close ties between potters in these towns (fig. 1). Norwalk’s reputation throughout southern New England for quality earthenware led retailers as early as 1812 and as far away as Boston to refer to the town’s products as “Norwalk ware.” The market for slip-script ware, however, was local, centered primarily in Norwalk and nearby Fairfield County communities.[7]

How this distinctive pottery came to be made in Norwalk is unclear. Historical precedents exist, such as epigraphic pottery made during the Samanid Dynasty in the ninth and tenth centuries in what are now Iran and Uzbekistan (fig. 2). Norwalk’s potters presumably had no firsthand knowledge of those dishes, bowls, and hollow wares, which feature written religious and secular sentiments that contrast with the dense, interlaced decorative patterns common on other Middle Eastern ceramics. First coated with a white engobe, they were then inscribed in blackish or purplish-brown slip in a stylized Kufic script that was also used to express the word of God in the Qur’an and on tiles decorating the façades and interiors of mosques and madrasahs. These stark inscriptions against a white ground (or white script on a dark ground) seem modern in appearance, and one does not need to understand Arabic to sense the significance of what is written. Moreover, the inscriptions are often arranged in a circle and thus endlessly repeat, further emphasizing their meaning. Epigrams offering good wishes to the owner, practical advice for daily living, or celebrations of generosity are not uncommon. On these wares the inscription is the decoration, and meaning is communicated not through symbols but directly, with words.

Metropolitan slipware made at Harlow in Essex County, England, during the seventeenth century bears slip-script aphorisms and references to the Bible and the king (fig. 3). No European precedent for this pottery is known, and no example having a history of ownership in Norwalk has been found. The lack of evidence for the direct transfer of this style from the Middle East to Harlow and then to Connecticut suggests that ornamenting pottery with writing developed independently in places widely separated by distance and time. Norwalk’s slip-script pottery may be viewed as the continuation of a practice that was used in the Middle East and found expression in England before it appeared in this New England town.[8]

Slip-script pottery was made elsewhere in Connecticut, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania both contemporaneously with Norwalk production and after it ended. Hervey Brooks (1779–1873), a potter in Goshen, Connecticut, produced a few initialed and dated pieces in the 1850s and 1860s (fig. 4), but his inscriptions are rudimentary and show no familiarity with Norwalk’s products. Closer parallels are found in the work of an unidentified potter who may have worked in Pennsylvania. This potter made dishes with slip inscriptions that express sympathy for the temperance and antislavery movements that had gained widespread support in the first quarter of the nineteenth century. Two dishes inscribed “Temperance / Health / Wealth” (fig. 5) indicate the benefits to be derived from abstinence. Another, counseling “Remember / him that is / in bonds” (fig. 6), relates to Hebrews 13:3 (KJV): “Remember them that are in bonds, as bound with them; and them which suffer adversity, as being yourselves also in the body.” The inscription is a reminder that the bondage and adversity suffered by one are shared by all.[9]

It was in 1830 that Franklin County, Pennsylvania, potter George Wolfkiel (1805–1867) arrived in Bergen County, New Jersey, and acquired the pottery established in April 1827 by Henry Van Saun (d. 1829) in New Bridge (now River Edge).[10] Several dishes attributed to Wolfkiel are inscribed with the first name of women—including Mandy, Sally, Molly, Ginny, and Lucy—that ends with the descending letter “y,” which is rendered with a long, coiled tail (fig. 7). A dish inscribed “Hard times / in Jersey” (fig. 8), referring to the financial panic of 1837, may be an early example of Wolfkiel’s work.

Slip-script earthenware in Norwalk and elsewhere might not have been so appealing without the availability of public education. Newspaper and book publishing flourished during this time, spreading news of contemporary events and social movements. The result was that printers, publishers, and potters were confident that the literate public was large enough to make their enterprises worthwhile.[11]

A 1910 article titled “The Homely Pottery of Old New England” illustrated a “platter of dull red-ware with slip decoration. Made in Connecticut seventy-odd years ago.”[12] The inscription on the dish appears to read “Angeline Cleveland,” which the article states is inscribed on one example. Although the author did not say where in Connecticut this and the other inscribed pieces mentioned in the article were made, we know that Angeline Cleveland was the wife of William Cleveland, a Norwalk clerk. The couple was married in 1844, and the dish may have been made for Angeline about the time of her marriage.[13]

The 1850 Norwalk census lists nineteen men as potters, several of them related by blood or marriage. In 1847, when the Reverend William C. Hoyt, minister of the South Norwalk Methodist Church, and his wife, Betsey, were preparing to leave Norwalk for the reverend’s next assignment, church members made a quilt as a going-away gift for the couple (fig. 9).[14] The quilt was composed of forty-eight individually sewn blocks of patterned, multicolored stars; in the center of each block is inscribed in ink the name of a church member. Several of the names belong to men whose occupations represent a sampling of the trades that were practiced in Norwalk, such as stone cutter Nathan D. Beers, hatters Nathan Kidney and Stephen Wilcox, wheelwright Samuel Waters, and shoemaker Hanford Wilcox.

Other blocks on the quilt bear the names of members of Norwalk’s potting families, including Knapp, Merrill, Quintard, Selleck, Smith, and Waters. The names of the New Hampshire–born potter Lorenzo Dow Wheeler (1800–1864) and his wife, Finetta Lewis Wheeler (1805–1892), are inscribed on two of the quilt’s blocks. The Wheelers moved from New York City to Norwalk between the births of their son Edward in 1828 and daughter Finetta in 1835. A rectangular dish inscribed “Finetta Wheeler” (fig. 10) may have been made for Mrs. Wheeler rather than the couple’s daughter because of the resemblance of the form and the exuberant full-name inscription and infill designs to the dish made for another adult woman, Angeline Cleveland. In 1853 Wheeler was making “mineral knobs for doors, furniture, and shutters . . . composed of red, black, and white clays, mixed together, burned, and covered with ordinary Rockingham glaze.”[15]

It has been suggested that the slip-script tradition was brought to Connecticut by New Jersey potters, although proof of this has not been found. The career of one Norwalk potter, however, provides circumstantial evidence of this transference. Absalom Day (1770–1843) was born in Day’s Bridge (later Chatham), a settlement in Morris County, New Jersey, where the Day family had figured prominently since its founding.[16] Day was a potter in New Jersey before he arrived in Norwalk by 1792, the year he married Betsey Hoyt Smith (1777–1861). Day worked for Asa Hoyt Sr. at his pottery located at Washington and Water streets in Old Well, which later became part of South Norwalk. In 1796 Day acquired Hoyt’s pottery, and it was still standing in 1847 when it appeared on a map of Norwalk (fig. 11) at the time it was operated by Day’s nephew through marriage, Asa E. Smith, and his son Noah Smith Day (1798–1871).[17]

In 1797 Absalom Day advertised that he “continues the business of making & selling Earthen Ware” made of “clay imported from New-Jersey” (fig. 12).[18] Norwalk grew as a pottery production center despite not having a potter’s field nearby to supply clay of the quality and in the quantity that the potters required. Some potters got clay that had been dug in Huntington, Long Island, then shipped to Norwalk by sloop, but Day got his clay from New Jersey, which he knew from experience was plentiful and of high quality. Moreover, by fashioning New Jersey clay into Connecticut pottery, Day linked his birthplace and the town where he lived for the remainder of his life.

Absalom Day was also an influential Methodist preacher who is credited with establishing the First Methodist Church in South Norwalk. Prior to the church’s construction in 1816, traveling Methodist ministers preached at Day’s home. In 1802 Bishop Francis Asbury (1745–1816) “preached at the Old Well, at Absalom Day’s, near Norwalk.”[19] While on a preaching trip in 1818 the Reverend George Coles (1792–1858) visited Day’s shop and observed an association between Day’s potting activities and scripture:

[After leaving New York City, I] passed to Norwalk, and put up with brother Absalom Day. . . . Brother Absalom Day followed the business of a potter. I looked into his workshop, and saw with interest what “power the potter hath over the clay, to make one vessel unto honor and another unto dishonor,” as for example, of the same lump he would make two jugs—one for the purpose of holding milk, and the other rum.[20]

Coles saw this passage from Romans 9:21 manifested in Day’s turning jugs for different purposes. Day knew the Bible and its references to potters, and he would have been familiar with the verse. It probably had occurred to him that some of his jugs were utilized for purposes that were at odds with biblical teaching, but how they were used was out of his control. Day may have viewed his potting as an extension of his ministry, with each activity mirroring and reinforcing the other.

Two slip-script earthenware dishes attributed to Absalom Day are the earliest Norwalk examples known. One, measuring over fifteen inches in diameter, is inscribed “Day’s / Pottery” (fig. 13) and was probably made to be displayed as a sign inside Day’s workshop. Slip lines applied with a triple-spouted slip cup and combed at intervals complete the dish. The capital letters of the inscription were worked with a tool and have a feathery appearance, recalling that the term feathering was another word for combing. Combed slip is not typically associated with New Jersey or Connecticut earthenware, but it is seen frequently on slipware made in eastern Pennsylvania and in Philadelphia, so Day was perhaps familiar with the Philadelphia practice before he moved to Norwalk.[21] Day’s dynamic script and the variety of decorative effects he incorporated into the dish’s slip design offer unquestionable proof of his artistry and craftsmanship. The ornamental capital letters differ from the script on later Norwalk ware, which is closer in appearance to writing on paper. This, and Day’s acquisition of the Hoyt pottery in 1796, indicate the sign was made before 1800.[22]

A second dish from the same time is a rectangular form ornamented with Day’s conjoined slip-script initials AD (fig. 14).[23] Surrounding the initials is a wreath of wavy, looping lines; copper oxide glaze was applied liberally both to the letters and the infill decoration in order to add green to the design after firing. The use of copper oxide is also more commonly associated with Pennsylvania earthenware, but the Wintons found numerous sherds with green glaze during their excavations of the waster at the Hoyt pottery site.[24] Whether Day introduced Hoyt to the use of copper oxide glaze or was taught its use by Hoyt is unknown. These two dishes are the only slip-script wares that are firmly linked to Day, and both have inscriptions that refer to him. Slip-script pottery might not have been part of Day’s regular production but instead was reserved for advertising and personal use, which could account for the lack of additional examples.

Day’s influence on other potters in Norwalk was long-lasting. The Gregory and Betts families had settled in Norwalk in the seventeenth century, and the Norwalk landmarks Betts’ Island, Betts Hill, and Gregory Point remain as evidence of their early association with the town. Born in Norwalk, John Betts Gregory (1782–1842) was apprenticed to Absalom Day, and it was in Day’s shop that he probably learned the slip-script technique. Their association underscores the professional and familial connections that would spread the slip-script style. Sometime before 1807 Gregory “had a good business offer from Huntington, L. I. which he accepted.”[25] This corresponds to the period when Samuel J. Wetmore operated a pottery in Huntington. Which pottery employed Gregory in unknown, but Huntington’s proximity to Norwalk and the strong commercial exchange between the two towns explains why a talented young Norwalk potter was recruited by a Huntington pottery and how slip-script earthenware dishes came to be made in Huntington in the 1850s (fig. 15).

Gregory returned to Norwalk about 1809 and then moved to Clinton, New York, a farming and mercantile center in Oneida County and the home of Hamilton College. In 1810 he purchased the pottery on College Street established by Connecticut native Erastus Barnes (1773–1807); four years later he acquired Barnes’s former house.[26] In May 1817 he announced in a Utica, New York, newspaper (fig. 16) that he “continues manufacturing EARTHEN WARE at his Factory in Clinton.” The advertisement also offered for sale his “elegant FACTORY, with convenient Rooms at one end for a family” and “all his Tools and Out-Houses necessary for making Earthen Ware.”[27] Gregory did not put his house up for sale, so presumably he intended to remain in Clinton. If he had intended to give up potting, however, his plans changed—perhaps because the pottery did not sell—because he continued to manufacture in Clinton for another fourteen years.

Gregory must have made a significant amount of utilitarian earthenware in the twenty-three years he worked in Clinton, but only two signed dishes from this time are known. The first is the earliest dated example of Norwalk-style slip-script earthenware (fig. 17). Inscribed in manganese slip, the dish might have been displayed in Gregory’s shop and perhaps was inspired by the memory of his former master’s large advertising dish. Gregory’s distinctive script can be identified by the capital letters B, D, and G, which are seen on several signed and attributed works.

The following year, Gregory made a dish for Harriet Gregory Ostrander (1790–1832); (fig. 18). Also born in Norwalk, Harriet was related to John; they were probably cousins. She and her husband, Captain William Ostrander, lived in Albany, New York, where William ran commercial sloops on the Hudson River. The inscription, written in white slip and manganese oxide draws at least as much attention to the dish’s maker as to its recipient. Gregory’s characteristic capital letters, the copper oxide, and inscriptions written in different colored slips differentiate his work from slip-script wares made later in Norwalk. His reference to this as a “Dish,” a term that would appear frequently on Norwalk slip-script ware made later, is the earliest example of an American pottery form identified in this way.[28]

“Why / Will you / Die” is inscribed on the third dish attributed to Gregory’s Clinton years (fig. 19). This chilling text has eluded interpretation, leaving questions about the nature of Gregory’s personality and why he would create the dish. Gregory was remembered as a “devout Methodist” whose Clinton home was a gathering place for itinerant preachers and believers from 1819 to 1827, as Day’s house had been in Norwalk.[29] Gregory expressed his religiosity and his knowledge of the Bible through his work. The inscription is taken from Ezekiel 18:31: “Cast away from you all your transgressions, whereby ye have transgressed; and make you a new heart and a new spirit: for why will ye die, O house of Israel?” The verse is a caution against spiritual death through sin. However, Gregory chose the most dismaying part of the verse to inscribe on the dish. By taking it out of its larger context, he seems to pose a question that most would be hard-pressed to answer if they considered it at all. But this fragment of a biblical passage would have been recognized by others who knew the complete verse. Gregory’s combination of white slip, white slip accented with copper oxide, and iron oxide adds power to the inscription’s meaning. Writing the word “Die” in iron oxide emphasizes the literal connotation of the word, its explicit meaning reinforced by the black letters.

The earliest identified Norwalk commercial slip-script earthenware was probably made in 1824, when the marquis de Lafayette visited the town during his American tour. At the Norwalk Hotel, Lafayette “received a throng of Norwalk’s best people in its parlors. The town went wild with enthusiasm and erected a triumphal arch on the bridge bearing in letters spelled in lights, ‘Welcome Lafayette.’”[30] It was probably Day’s Pottery that capitalized on the affection that Norwalk’s citizens displayed for the last living Revolutionary War general by making dishes inscribed “Lafayette” and “Washington / & / Lafayette” (figs. 20, 21).[31] These dishes have been found in sufficient numbers to indicate they were popular souvenirs of the general’s visit.[32]

In 1825 Absalom Day transferred control of his Norwalk pottery to his nephew Asa E. Smith, who had been Day’s apprentice beginning in 1812. Smith presumably continued working with his uncle until he took over the shop. The reason Day stopped potting and directed his energies to his farm was likely ill health. Many potters suffered physical ailments associated with breathing clay dust and working with lead glaze, and at age fifty-five Day might have been unable to continue working. From November 1827 through February 1829, an advertisement for “Trotter’s Genuine Pectoral of Horehound” carrying Day’s written endorsement of the product appeared more than two hundred times in New York City’s Commercial Advertiser. “For about four years,” Day wrote, “I was afflicted with a violent cough, attended with all the symptoms of a confirmed pulmonary complaint. So great was my debility, that I was unable to attend to my business or public duties.”[33] The appearance of Day’s symptoms corresponds to the period shortly before he transferred the pottery to his nephew.

Probably encouraged by the success of the Lafayette dishes, Asa E. Smith expanded production, adding other inscriptions to his wares. To do so required the skills of a literate potter who was expert in the drape-molding process and the use of a coggling wheel. In 1686 English naturalist Robert Plot described the slip used by potters in Staffordshire, England, to decorate earthenware as being composed of clays that are “looser and more friable” than “throwing clays.” Slip clay was “mixed with water they [the potters] make into a consistence thinner than a syrup, so that being put into a bucket it will run out through a quill; this they call slip, and is the substance wherewith they paint their wares.”[34]

Writing with slip required that it be viscous enough to flow easily and adhere to the surface, but not so thin that it ran after it was applied. Great skill was required both to write with a single-quill slip cup in an attractive Spencerian script that fit comfortably on the dish and to avoid errant drips. The decorator needed to visualize the completed inscription before starting as there was only one opportunity to do it correctly. Misspellings abound, indicating that such errors did not automatically require a piece to be discarded. From the start, the inscriptions show little hesitation and appear to have been written quickly and confidently by a practiced hand. This decorator’s self-assurance is seen in the S-scrolls above and below “Lafayette” and the repeating loops of slip trailing from the capital W in “Washington.” The capital W also appears on dishes inscribed “William / & / Mary” (fig. 22) commemorating the dual sovereigns who signed the English Bill of Rights that inspired resistance to British rule in North America.[35]

That same script is seen on Norwalk dishes made over the course of many years. The Wintons wrote, “It is stated that this workman was a man named Chichester.” They did not identify their source, but the claim persisted and has evolved into a common belief that Henry Chichester was the decorator. Two Henry Chichesters lived in Norwalk in this period: Henry Chichester Sr. (1762–1849), who was born in Huntington, Long Island, and married Deborah Hoyt; their son Henry Jr. (1799–1847) was a potter who before 1825 made buttons, doorknobs, and earthenware in Norwalk in partnership with his brother-in-law James Quintard under the name “Chichester & Quintard.” Henry Jr., therefore, might be a candidate. However, no evidence that either Henry Sr. or Henry Jr. had worked for the Smith Pottery has been found. Moreover, a Norwalk dish dated 1854 was made several years after both men had died.[36] As satisfying as it would be to identify the decorator with confidence, the inability to do so does not diminish this potter’s achievement or the significance of his contribution to the history of Norwalk pottery.

Gifting pottery, whereby parents gave pottery to their children when they were young or to assist them in setting up households as they approached adulthood, was probably more common in early America than is generally realized. Norwalk slip-script dishes bearing names and initials outnumber other inscriptions by a wide margin. These dishes probably represent a small fraction of the total number made, indicating that the practice of making personalized pottery to commemorate births, marriages, and other milestones in life was fairly common in Norwalk. Slip inscriptions fall into several categories: names and initials, foods, place-names, biblical texts, patriotic sentiments, aphorisms, and names of saints. Numerous dishes with inscriptions such as “Nancys / Dish,” “Lucys Dish,” and “Sarahs Dish” (fig. 23) were likely made for children, similar to the personalized dishes and bowls that parents purchase for their children today.

Others bear only the initials of individuals, including six that are inscribed with both “CB” and “WB”; one each lettered “HB,” “NB,” and “SB”; and three initialed “DE.” The reason for the duplicates and the surnames involved are not known, but it is possible they were made for members of the same two families. Full names, such as “Angeline Cleveland” and “Finetta Wheeler” mentioned earlier, appear only occasionally. A dish inscribed “Francis / Smith / Norwalk” (fig. 24) might identify Francis H. Smith, the infant son of Asa Smith’s brother Ward. Born in New York City in 1850, Francis died at age two months and was buried in Norwalk. If the dish was made to celebrate the child’s birth, its significance soon changed to become a poignant reminder of the family’s loss.[37]

Seven dishes made for individuals whose first names start with the letter E have script that differs somewhat from the examples discussed thus far. One of two inscribed “Elsey” (fig. 25) typifies the others with its more vertical script and a capital E that begins with a large loop.[38] None of the seven dishes includes a surname, which suggests they were made for children. The infill motifs of looping and coiled lines are bolder than the more restrained straight and wavy lines and S-scrolls seen on the majority of Norwalk pieces. It is noteworthy that on both of the “Elsey” dishes the decorator did not leave sufficient room for the descending letter y, which therefore had to be written horizontally so it would fit on the dish. This anomaly might indicate the hand of a second decorator. However, the same capital E appears on a dish inscribed “Remember / thy Last / End.”[39] If two potters were employed by Smith to inscribe dishes, this would be evidence that inscribed ware was not just a sideline but an important part of the pottery’s production.

Earthenware dishes were used for preparing and serving foods, and several inscriptions document the foodways of the town in the second quarter of the nineteenth century. Native Americans had harvested oysters from Long Island Sound’s rich oyster beds and dug clams in coastal areas for millennia. In 1721 the town prohibited anyone other than its residents from “rakeing and gathering of Oysters within ye harbours, coves, or any other place appertaining and being within the limits of our township.”[40] Norwalk’s numerous oystermen harvested the shellfish, which, along with clams, provided food and income for many families. The importance of shellfish to the local diet and economy is preserved on dishes inscribed “oysters & Clams” (or “Clams & oysters”) and “Clam Potpie” (fig. 26). “Plumb Pudding” (fig. 27) and “Apple Pie” offer glimpses of English dishes that colonists brought to America and the fruits grown in local orchards. The unglazed bottoms of some dishes have been blackened by fire, but others are not. Because the dishes were relatively inexpensive and decorative, some owners did not feel compelled to use them for preparing food but instead chose to use them as serving dishes or for display.

Absalom Day directed the spiritual lives of many South Norwalk residents, which accounts for numerous dishes inscribed with religious sentiments and the names of saints. The Bible had been a powerful force in Connecticut since the earliest period of settlement, and dishes bearing biblical passages and related epigrams found a strong market in Fairfield County. The inscriptions “forgive / all injuries” and “Pray for / the Living / & the / Dead” (figs. 28, 29) are two of the seven acts of corporal mercy that Christians are expected to perform.

Two dishes inscribed “Honour / the / humane” (fig. 30) served as reminders to acknowledge compassionate behavior in others and incorporate the attribute into one’s life. While “sin the / misery of / man & / woman” (fig. 31) is not from scripture, the link between sin and suffering is found throughout the Bible.

Customers of the Smith Pottery could order dishes inscribed with the names of saints who served as models for a Christian life. The number of extant examples is large, with those inscribed “st. / francis / xavier” and “st / Remigius” (figs. 32, 33) typifying most. Among the favorites were martyred saints, two of whom had died or whose remains were rediscovered about the time that Connecticut was settled: “st. / fidelas / Martyr” commemorates the man who died at the hands of Calvinists in 1622 (fig. 34), and “St Martina / Virgin & / Mayrter” died in 226; her burial site was discovered in 1634. By preserving the names of individuals who gave their lives for their faith, the dishes can be seen as an extension of the Methodist Church’s ministry in Norwalk.[41]

John Betts Gregory left Clinton and returned to Norwalk in 1831. He purchased Half Mile Island (now Canfield Island) and built kilns for burning earthenware and stoneware in the “cholera year” of 1832. He apparently resumed making slip-script pottery on his return. Three dishes attributed to Gregory that may have been made in Norwalk include an oval dish inscribed “Ware / plenty Come / and buy” (fig. 35). Featuring a flag on the capital W that identifies his hand, Gregory’s characteristic streaks of copper oxide give this inscription vitality that is lacking in his Clinton works. This advertisement in clay may have hung in Gregory’s Norwalk pottery to demonstrate his skill and the quality of his ware.

Gregory inscribed another oval dish “This is / Good Enough / For Rich / Folks” (fig. 36). Vertical streaks of copper oxide give the word “Folks” surprising dimensionality and depth that are absent on ware from the Smith Pottery. This inscription recalls “The best is not too good for you” inscribed on slipware made in the eighteenth century by Staffordshire potters. Gregory’s sentiment, however, has an edgy ring to it, as if he were scolding the wealthy for not patronizing his pottery or for believing that his products were fit only for the middle class. Evidence of Gregory’s distinctive personality may support this. In Clinton he was remembered as “quite a recluse, being seldom seen outside of his own premises,” but a “genial soul” who “loved to scatter jokes and bits of humor among old and young who came to inspect his work or buy his wares.” It is said that Gregory often sang while he worked, one of his favorite spirituals being “The Potter and His Clay.” The lyrics were inspired by the same biblical passage in Romans that the Reverend Coles was reminded of as he watched Absalom Day at work:

Behold the potter and the clay!

He forms his vessels as he please.[42]

Celebrating the potter’s independence, the verse seems to have been important to this man who spoke his mind directly and freely through his work.[43]

Norwalk ware was sold at the potteries, it was shipped on sloops to sell in coastal Connecticut communities, in Massachusetts, and in New York City, and it was carried into the surrounding countryside by peddlers. The inscriptions “Break / Away / more / making” (fig. 37) and “Cheap Ware” refer to the affordability of Smith’s ware, with “Cheap” meaning inexpensive, not of low quality. Making use of the word “cheap” must have been an effective marketing tool. Two dishes bear the inscription “pony / up the / Cash” (fig. 38), which might be a playful encouragement of sales. Inscribed Norwalk dishes average about 11 inches in diameter, but they range from 8 inches to more than 14 inches. A price list for “brown earthenware” published in 1864 by A. E. Smith’s Sons lists 11-inch “baking dishes” priced at $1.00 per dozen, or about 8 cents each.

The Smith Pottery appears on an 1836 drawing of Old Well on Water Street adjacent to docks at the south end of Norwalk harbor (fig. 39). A detail at the bottom of the drawing shows the pottery house on the left, a gable-fronted building on the right that may have housed a retail shop, and smoke labeled “yellow ware” billowing from a single bottle kiln. Asa E. Smith and Noah Selleck were in partnership under the name Selleck & Smith from 1837 to 1843. This was the first of several organizational changes the Smith firm underwent in succeeding years. Absalom Day died in 1843, the year that his son Noah and Asa Smith formed the firm Smith & Day. This partnership continued until 1848, when Smith and his son Theodore, who managed the pottery’s wareroom at 38 Peck Slip in New York City, formed A. E. Smith & Sons. From about 1850 until 1860, Norwalk stoneware stamped “A.E. Smith & Sons, Manufacturers, 38 Peck Slip, N.Y.” was sold in New York City. The importance of that market for Smith’s ware is documented by a dish inscribed “Newyork / City” (fig. 40).

Nationalistic inscriptions such as “United / States” (fig. 41) bring to mind the early “Lafayette” and “Washington & Lafayette” dishes. In 1851 Lajos Kossuth (1802–1894), a leader of Hungary’s struggle for independence from Austria, arrived in the United States to tour the nation. Kossuth was the first foreign dignitary to address a joint session of Congress since Lafayette, and he was feted at the White House in 1852. Unlike Lafayette, Kossuth did not visit Norwalk, but popular support for him and Hungary’s bid for self-rule was strong, prompting Smith to produce a dish inscribed “Kossuth / 1852” (fig. 42). This being the only known example of this dish suggests it did not gain wide popularity.

Potters occasionally made personal items for their own amusement or as gifts for family or friends. Known as “end of the day” pieces, they can be sculptural works that were fashioned from clay into animal or human forms. They are often a significant departure from the kind of ware the potter made day in and day out. A Norwalk dish bears the only inscription referencing the work of potters: “This is / the last / for to / day” (fig. 43). The dish bridges production work and novelty, making it possibly the earliest known example of this ware. A standard form produced by the pottery was given a personal message that brings the long days and repetitive work of potters down to a very personal level.

The 1850s were especially rewarding for Asa E. Smith. In 1850, when his occupation was listed as “potter,” the value of his real estate was $9,000. Ten years later, now owner of a “Stone Ware Factory,” his real estate was valued at $45,000 and his personal estate $15,000. His income grew substantially as his firm’s stoneware found a growing market not just locally but also in New York City and elsewhere in the United States, where Smith’s stoneware was shipped by rail. His success over decades might be attributed to a belief that “Honesty / is the Best / of polacy,” which is inscribed on one of his firm’s dishes (fig. 44).

On February 14, 1854, Smith advertised in the New-York Daily Tribune his “desirable country residence” on Norwalk’s East Avenue for sale, one day after the dish that serves as the keystone for identifying Norwalk slip-script earthenware was made (fig. 45).[44] “Norwalk / feby the 13 / 1854” was inscribed by the artisan who had lettered dishes for thirty years. That the manufacture of this dish and Smith offering his house for sale occurred a day apart seems beyond coincidence. Perhaps the dish held special significance for Smith by signaling the end of his pottery’s production of slip-script earthenware and the firm’s emphasis on marketing stoneware regionally. Norwalk is given prominence in the inscription, acknowledging the place whose residents had supported Smith, Absalom Day, and John Betts Gregory for more than fifty years. If the dish was among the last of its kind made by Smith’s pottery, it was a fitting tribute to the town and to the potters whose earthenware carried messages that would continue to resonate nearly two centuries later.[45]

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

For their assistance with the preparation of this article, I sincerely thank Anthony Butera, Brian Cullity, Robert Hunter, Suzanne Katz, Angelika Kuettner, Melissa Maichele, Lewis Scranton, Nancy and Gary Stass, and the High Museum of Art.

“Antiques Auction,” Norwalk Bulletin, September 2, 1953.

Andrew L. Winton and Kate Barber Winton, “Norwalk Potteries,” Old-Time New England 24 (1934): 75–92.

Ibid., p. 80.

Ibid., pp. 90–91.

Albert Hastings Pitkin, Early American Folk Pottery, Including the History of Bennington Pottery (Hartford, Conn.: Case, Lockwood & Brainard Co., 1918), p. 92.

Edwin Hall, The Ancient Historical Records of Norwalk, Conn. (Norwalk, Conn.: James Mallory & Co., 1847), p. 173.

A reference to “Norwalk Ware” appeared in an advertisement placed by New Haven, Connecticut, merchant Ebenezer Huggins in the Connecticut Herald, June 9, 1812. In 1822 the schooner Galen docked in Boston to sell “a small quantity of Norwalk WARE; viz. Baking Dishes, Butter Pots, Wash Bowls, Jars, &c.” The Repertory, January 10, 1822. Dishes inscribed “City of Troy” and “New York City” indicate that the ware was also made on order or on speculation for New York customers, though Fairfield County remained the primary market. The “City of Troy” dish was brought to the author’s attention by Kathryn T. Sheehan in an email, February 14, 2015.

Inscribed earthenware was made beginning in the late eighteenth century by several Pennsylvania-German potters who mastered the sgraffito technique of scratching images and inscriptions through a contrasting coating of slip to reveal the darker clay body beneath. This ware employs a different technique: the inscriptions are typically located on the perimeter of the dish and they often address relationships between men and women. These differences, along with the geographical and cultural distance between New Englanders and German Americans, distinguish this Pennsylvania pottery tradition from that of Norwalk.

Sotheby’s, Important Americana, sale NO7025, October 9, 1997, lot 159.

Kevin Wright, “Potters along the Hackensack River (Bergen County) 1805–1867,” www.bergencountyhistory.org/Pages/BCHSPottery.html (accessed January 10, 2015).

Stanley L. Engerman and Robert E. Gallman, “The Emergence of a Market Economy before 1860,” in A Companion to 19th-Century America, edited by William L. Barney (Malden, Mass.: Wiley-Blackwell, 2006), p. 133.

Angeline Scott Donley, “The Homely Pottery of Old New England,” Country Life in America 19 (1910): 46.

1850 Federal Census for Norwalk, Fairfield, Connecticut, roll M432_38, p. 143B, image 292.

Collection of the Stamford Historical Society, Stamford, Connecticut.

Edwin Atlee Barber, The Pottery and Porcelain of the United States (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1893), p. 181. Several men in the 1850 Norwalk census listed their occupations as “button maker,” suggesting that Norwalk was a center of button production.

Charles A. Philhower, Brief History of Chatham (New York: Lewis Historical Publishing Co., 1914), p. 10.

Winton and Winton, “Norwalk Potteries,” p. 85.

Republican Journal, February 4, 1797.

Francis Asbury, The Journal of the Reverend Francis Asbury, 3 vols. (New York: N. Bangs and T. Mason, 1821), 3:65. Day built “a substantial house in the Georgian style of architecture” that was razed in 1876 to make way for a business block. [Samuel Richards Weed], Norwalk after Two Hundred & Fifty Years: An Account of the Celebration of the 250th Anniversary of the Charter of the Town, 1651—September 11th—1901 (South Norwalk, Conn.: C. A. Freeman, 1901), p. 302.

Coles continued: “One thing more I observed: the potter made no vessel for the purpose of destroying it. This fact, I thought, might convince the most skeptical, if he wished to be convinced, that if capricious man never made a vessel for the purpose of breaking it to pieces, the just and holy God never created a single human soul for no other object than to show forth his power in destroying it.” Rev. George Coles, My First Seven Years in America (New York: Carlton & Phillips, 1852), p. 48.

Barbara H. Magid and Bernard K. Means, “In the Philadelphia Style: The Pottery of Henry Piercy,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2003), pp. 47–86.

A small raised heart is molded into the back of the dish, which has short parallel lines incised around the perimeter and crudely fashioned letters “AW” in the center. It would be reasonable to assume that these are the initials of the potter who made the dish. Transporting clay from New Jersey, marketing his ware, and preaching took Day away from Norwalk for weeks at a time, and he would have relied on other potters to run the pottery in his absence. Still, it seems unlikely that Day would have entrusted an employee to make this sign for his own pottery. The names of the individuals who are known to have apprenticed to Day do not match these initials, and the only identified Connecticut potter having those initials is Ashbel Wells Jr. of Hartford, who opened a store in Hartford in 1787—predating Day’s Norwalk work. Melissa Maichele, email to author, January 5, 2015. For information about Ashbel Wells Jr., see William DeLoss Love, The Colonial History of Hartford Gathered from the Original Records (Hartford, Conn.: William DeLoss Love, 1914), p. 177.

The practice of using conjoined initials was common in the American colonies in the eighteenth century. Day’s initials resemble conjoined initials carved on the gravestones of six members of the Day family who died between 1802 and 1815 and are buried in Hillside Cemetery in Chatham, New Jersey. Day’s travels may have taken him to Chatham to visit family or to attend the funerals of some of these relatives where he saw the gravestones and appropriated the motif.

Winton and Winton, Norwalk Potteries, p. 83.

Rev. Charles M. Selleck, Norwalk (Norwalk, Conn.: Charles M. Selleck, 1896), p. 31.

William C. Ketchum Jr., Potters and Potteries of New York State, 1650–1900 (Syracuse, N.Y.: Syracuse University Press, 1987), p. 271.

Columbian Gazette (Utica, N.Y.), June 3, 1817.

An advertisement in the Philadelphia Inquirer in 1839 offered for sale pie plates “made expressly to stand the fire in baking”—a spurious claim given that the heat of the kiln in which earthenware was fired was far greater than a household oven, so baking food in earthenware dishes would not harm them. Savory and sweet pies could feed a family at little expense, so these baking wares were common in American households.

A dish inscribed “E Selby / Conover” may document a previously unrecorded partnership between Edward Selby and Abraham Conover, who were potters in Poughkeepsie, New York. Copper oxide was applied liberally to both the inscription and the infill decoration on the dish, recalling Gregory’s practice. Harriet Ostrander lived in Albany County, so it is conceivable that Gregory secured other commissions in the area. However, why Poughkeepsie potters would commission an outsider to make this promotional dish is unclear, and an attribution to Gregory remains tentative. See Ketchum, Potters and Potteries of New York State, pp. 116–17, and Sotheby’s, Americana, sale NO8158, January 22, 2006, lot 265

Rev. A[mos] D[elos] Gridley, History of the Town of Kirkland, New York (New York: Hurd and Houghton, 1874), pp. 107, 165.

Connecticut Daughters of the American Revolution, Norwalk Chapter, The Colonial and Revolutionary Homes of Wilton, Norwalk, Westport, Darien and Vicinity (Norwalk, Conn.: DAR, Norwalk Chapter, 1901), pp. 44–45.

A dish inscribed “Lafayette & Jackson” (private collection) links Lafayette, a hero of the Revolutionary War, and Andrew Jackson, who was celebrated as a hero in the War of 1812.

Earthenware dishes having molded profiles of Lafayette and Washington are attributed to Bergen County, New Jersey, potter Henry Van Saun (d. 1829). Wright, “Potters along the Hackensack River (Bergen County) 1805–1867.”

Commercial Advertiser (New York, N.Y.), November 29, 1827. Day’s endorsement, dated October 1827, continues: “my friends all thought me in decline; and after taking every medication recommended, without effect, I was resigned to my fate, and looked forward to the grave as the only place of relief. . . . [T]he first bottle afforded relief; and by continuing to use it, I have been restored to my usual health and strength.” No evidence that Day returned to making pottery after 1825 has been found, however.

Robert Plot, The Natural History of Stafford-shire (Oxford, Eng., 1686), p. 122. Plot was keeper of the Ashmolean Museum and professor of chemistry at Oxford University. The process of turning, decorating, and burning earthenware has little changed from how he describes it.

Tin-glazed earthenware dishes bearing images of King William and Queen Mary were made in England from the time Mary ascended to the throne in 1689 to her death in 1694. The couple may not have been commemorated on ceramics again until Norwalk potters did so.

For information about Henry Chichester Jr.’s activities, see Herbert Armstrong Poole, The Genealogy of John Lindsley (1845–1909) and His Wife Virginia Thayer Payne (1856–1941) of Boston, Massachusetts (Milton, Mass.: Herbert Armstrong Poole, 1950), p. 263.

“Connecticut Deaths and Burials, 1772–1934,” database, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:F7KF-C4R [accessed March 27, 2015]), Francis H. Smith, May 20, 1850; citing reference 368; FHL microfilm 3,355.

The names on the other dishes are “Enos,” “Enoch,” “Elennor,” and two dishes are inscribed “Emma.”

This inscription is from Ecclesiasticus 7:40: “In all thy works remember thy last end, and thou shalt never sin.” The verse refers to the common belief that the sins one committed in life will be tallied on Judgment Day. A variation of this inscription, “REMEMBER THY END TRULY,” is written on a seventeenth-century Metropolitan ware pot. John Eliot Hodgkin and Edith Hodgkin, Examples of Early English Pottery Named, Dated, and Inscribed (London, Eng., 1891), p. 53.

Edwin Hall, The Ancient Historical Records of Norwalk, Conn., with a Plan of the Ancient Settlement, and of the Town in 1847 (Norwalk, Conn.: James Mallory & Co., 1847), p. 110.

“St. Eulogias,” a misspelling of St. Eulogius of Córdoba, is inscribed on another dish.

Gridley, History of the Town of Kirkland, p. 165; Samuel W. Durant, History of Oneida County, New York (Philadelphia, Pa.: Everts & Fariss, 1878), p. 464; Isaac Watts, Hymns and Spiritual Songs (London, Eng.: Printed for W. Strahan et al., 1773), p. 92.

This trait is seen on a dish inscribed “For / Hansom / Molly” (Connecticut Historical Society). Considering the mores of the time, Gregory’s observation seems surprisingly bold.

New-York Daily Tribune, February 14, 1854. No evidence that Smith sold the residence in which he had lived since at least 1847 has been found. Census lists for 1860 and 1870 show Smith living among the same East Avenue neighbors as earlier.

The recent discovery of Norwalk slip-script earthenware in archaeological contexts in Brooklyn, Manhattan, and Staten Island provides additional evidence of the wide appeal of Asa E. Smith’s ware. More such finds are inevitable and will expand our understanding of the popularity of this distinctive pottery and the meaning it held for customers living far from where it was made.