Russell Aitken, Wyoming Europa, 1939. Glazed earthenware. H. 12". (Private collection; photo, Randl Bye.)

Tile mosaic, Europa Abducted by Zeus Transformed into Bull, Byblos, Lebanon. Roman era, 3rd century A.D. (De Agostini Picture Library, G. Dagli Orti, Bridgeman Images.)

Maerten de Vos (1532–1603), The Rape of Europa, ca. 1590. Oil on oak panel. 52 5/8" x 68 11/16". (Museo de Bellas Artes, Bilbao, Spain, Bridgeman Images.)

D. Gerolina, (left) Europe and Asia and (right) America and Africa, England, ca. 1807. Reverse painting on glass. 14" x 10". (Private collection.)

Candlestick depicting Europa and the Bull, Charles Gouyn’s Factory, London, England, 1750–1760. Soft-paste porcelain. H. 7 11/16". (© Victoria and Albert Museum, London.)

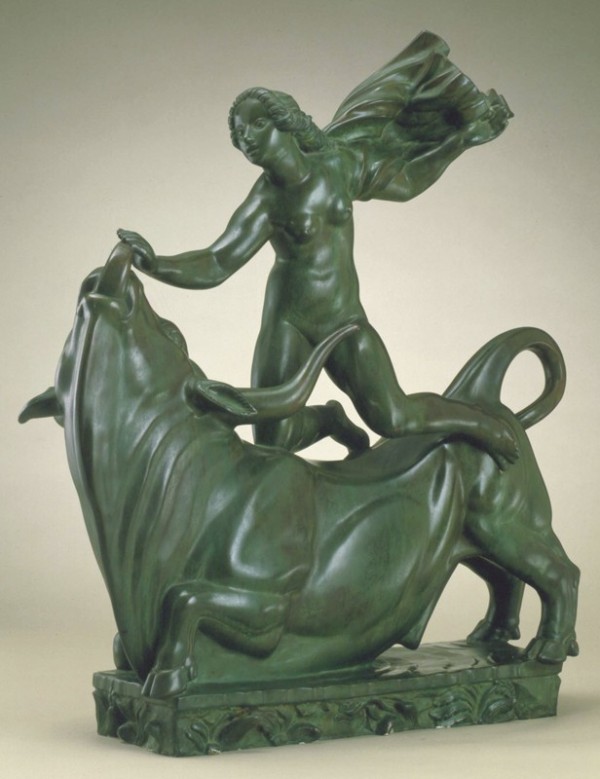

Carl Milles, Europa and the Bull, Study for Large Fountain, 1926. Bronze. H. 31". (Cranbrook Foundation, gift of George Gough Booth and Ellen Scripps Booth; archive photo, courtesy Cranbrook Art Museum.)

Paul Manship, Europa and the Bull, 1924. Bronze. H. excluding marble base 9 1/2". (© Christie’s Images Limited 2016.)

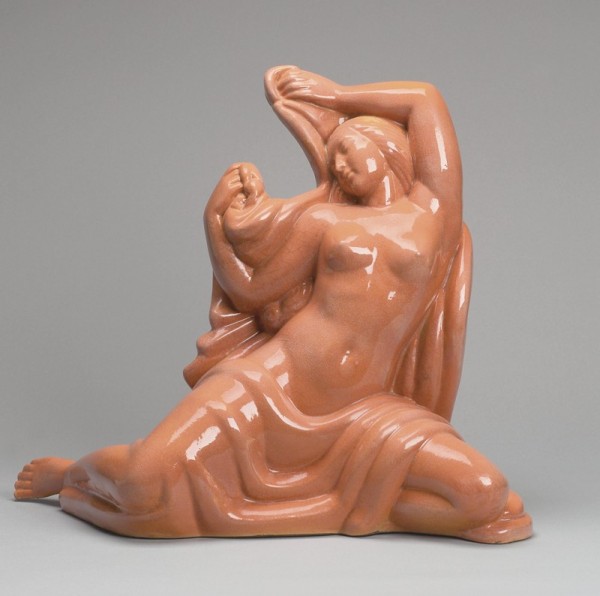

Paul Manship, Europa, for the Cowan Pottery Studio, Rocky River, Ohio, ca. 1928. Earthenware with “terra cotta” glaze. H. 15". (Cowan Pottery Museum, Rocky River Public Library.)

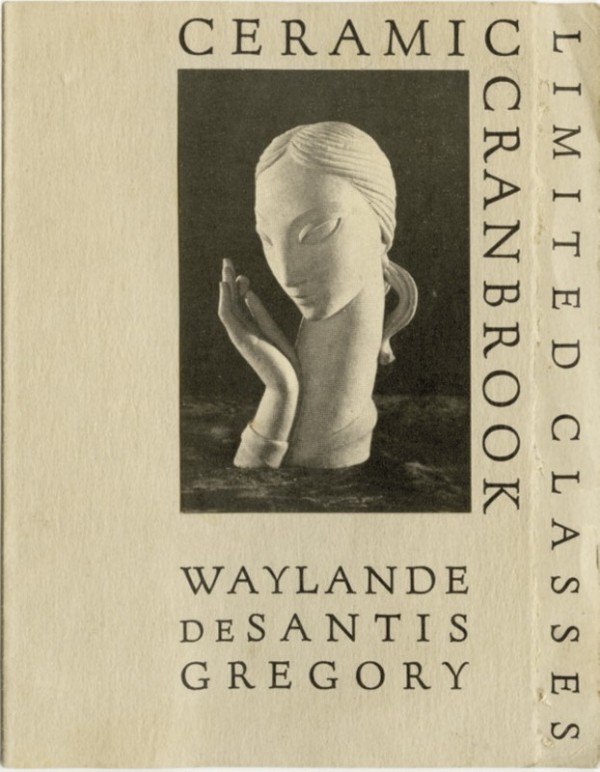

Cranbrook brochure, 1932, showing Waylande Gregory’s Girl with Olive, 1932.

Waylande Gregory, Europa and the Bull, ca. 1934. Earthenware. H. 23". (Everson Museum of Art, museum purchase.)

Valerie (“Vally”) Wieselthier, Europa and the Bull, 1938. Glazed earthenware. H. 25". (Private collection; photo, Randl Bye.)

Viktor Schreckengost, The Abduction, 1938. Glazed earthenware. H. 14". (Viktor Schreckengost Foundation.)

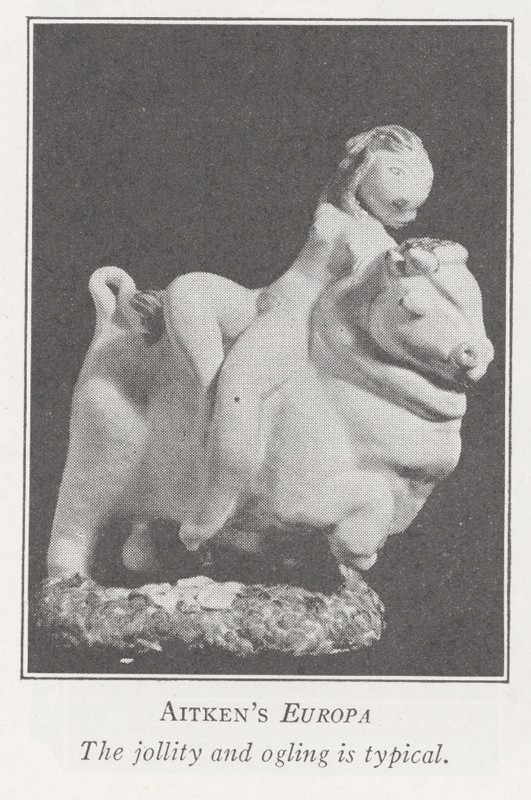

Russell Aitken, Europa, ca. 1935, glazed earthenware. Dimensions unrecorded. (Collection unknown; photo from Time, October 18, 1937.)

Charles (“Chuck”) Yerkes Dusenbury, Europa and the Bull, 1940. Glazed earthenware. H. 14". (Cranbrook Art Museum, gift of the artist.)

Irene Roosevelt Aitkin, the second wife of ceramic artist Russell Barnett Aitken (1910–2002), donated a collection of her husband’s ceramic sculptures to the Cleveland Museum of Art in 2013. Among the items is a study collection of ceramic maquettes made by the artist and a scrapbook relating to his career in ceramics. Russell Aitken, a Cleveland native who graduated as valedictorian from the Cleveland Institute of Art, was considered a leading American ceramist. One of the ceramic maquettes was for his Wyoming Europa (fig. 1). The maquette, 12 inches high, is marked only with his initials, RBA. The finished version, which is illustrated in the scrapbook on a page taken from an unidentified magazine, was recently discovered in the collection of the noted furniture designer Harold M. Schwartz in San Miguel de Allende, Mexico.

This article focuses on seven ceramic and two bronze sculptures dating from the 1920s to 1940 that all illustrate the theme of Europa and the Bull except for one, which depicts only Europa. All of the artists were American-born except for Carl Milles (1875–1955), who was from Sweden, and Valerie (“Vally”) Wieselthier (1895–1945), from Austria, major European artists who had established careers before they came to the United States. All told, the nine sculptures show a progression in style and meaning. Aitken’s Wyoming Europa is the penultimate version, where, in effect, we see the Americanization of Europa. The Cowan Pottery in Rocky River, a suburb of Cleveland, and the Art Academy of Cranbrook, in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan, are also significant in this development.[1]

The Myth of Europa as Allegory

The image of the mythological Europa has always been an allegory for the origins of Western, or European, civilization. In Greek mythology Europa, a woman of Phoenician origin, was the mother of King Minos of Crete. Zeus fell in love with her and adopted the form of a white bull in order to abduct her (fig. 2). When Europa mounted his back, Zeus flew over the Mediterranean and landed on the island of Crete. He then took human form and laid with her. Their offspring were Minos, Rhadamanthus, and Sarpedon. Minos became the king of Crete and the Minoan civilization was named after him.

The ritual of the taming of the bulls dates as far back as about 1500 B.C. in Crete. The Minoans fostered a bull culture, and bull vaulting and bull sacrifices were an integral aspect of their strange and still little-understood religious practices, involving both young men and women vaulting over charging bulls, as is depicted in Minoan frescoes. The American sport of bull riding, developed during the expansions of the western territories, has its parallels to the ancient Greek rites. In the American practice, a rider mounts the bull and with one hand tightly grips a flat braided rope tied around the bull. When the bull is released, it bucks, rears, and kicks, trying to throw off the rider. For the ride to count, the rider must stay atop the bull for at least eight seconds—what has been called the most dangerous eight seconds in sports.

The allegory of Europa and the Bull had considerable political symbolism throughout its history well into modern times. And its manifestation in works of art—in painting and sculpture—reflected the prevailing political and social milieu. Europa and the Bull was the subject of many old master paintings in the sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries (fig. 3). Various incarnations of Europa, sometimes with the bull and sometimes as a stand-alone figure, were depicted with allegorical images of Asia, Africa, and America beginning in the sixteenth century (fig. 4). In the eighteenth century the Meissen factory, the first factory to produce hard-paste porcelain in Europe, introduced its version of this subject. The figure was subsequently copied by other European and British ceramic factories and produced into modern times (fig. 5).

In 1939 Americans increasingly feared that the United States might be called to defend Western civilization as the conflict in Europe grew. It was at this time that Aitken transformed the essence of an ancient Cretan myth into something that referenced the mythology of the American West, Wyoming Europa (see fig. 1). In Aitken’s portrayal, the rider is a cowgirl who wears a cowboy hat and western boots. This Europa does not even ride sidesaddle, as women typically did. She is full of American confidence and has the bull under control. Although Wyoming Europa can be seen as a barometer relating to America’s concern for the events in Europe, its mood is jocular, not fearful.

The same year Aitken created Wyoming Europa, the World’s Fair opened in New York. Situated historically between the Great Depression and World War II, the fair proved to be a microcosm of the rapid changes occurring in the larger world. With the theme “Building the World of Tomorrow,” it was opened by President Franklin D. Roosevelt on April 30, 1939, and was hailed as the greatest international exposition in history. Sixty foreign nations participated—Germany was the only major power that did not.

Carl Milles

Sweden, which did not participate in either world war, was nevertheless affected by the New York stock market crash of 1929 and experienced a financial depression in 1930 and 1931.[2] The country’s economic problems seemed not to have much effect on its leading sculptor, Carl Milles, however.[3]

Milles is probably best remembered in the United States for two bronze sculptural fountains (ca. 1934–1937) that he created to enhance the grounds of the Art Academy buildings of Cranbrook. The buildings, designed by Finnish architect Eliel Saarinen, and Milles’s sculptures present an exemplary—and unusual—unity of design. Milles had studied from 1897 to 1904 in Paris, where he came under the influence of Auguste Rodin, as did many young sculptors at that time. But later, while Milles was living in Munich, the late-nineteenth-century German sculptor Adolf von Hildebrand had a more substantial and long-lasting influence.

The Cranbrook Art Academy wanted Milles to join the faculty as a resident artist in the early twenties, when Milles was first establishing his reputation; in time, the school became more aggressive in the effort to bring him to America and offered him a professorship.

Milles was well known in the United States before his appointment at Cranbrook. In 1929 he was in a group exhibition of European sculpture at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and in 1931 the City Museum of Saint Louis mounted his first comprehensive exhibition, which then traveled to the Detroit Institute of Arts, the Cleveland Museum of Art, and the Brooklyn Museum. Milles had first visited Cranbrook in 1929 and received the position of professor of sculpture in 1931. Cranbrook treated Milles well, well beyond how other resident artists were treated. In fact, the school did not even require him to offer formal instruction; modeling, casting, and other sculptural practices were offered by other instructors, and Milles would lecture advanced students while criticizing their work.[4] In 1951 he retired from Cranbrook and returned to Sweden.

Milles had created a bronze Europa sculpture, commissioned in 1919, for the marketplace in Halmstad, Sweden. Conceived in Sweden, his Europa is probably the most European. His reductive figures display modern tendencies but they also indicate a reluctant interest in Art Deco. Cranbrook has a replica of this Europa sculpture that was cast in 1926 (fig. 6) and is 31 inches tall. Cranbrook also has a larger, outdoor version, also cast in 1926, which is 112 inches tall and positioned at the top of a series of descending pools, where bronze nude male tritons support fish that squirt jets of water. Milles’s figure of Europa is kneeling precariously on the bull’s back, the moment of conception suggested by her touching the bull’s elongated tongue. The bull is depicted with its front legs low to the ground and its hind legs elevated. Art historian Joan Marter explains, “The animal is not shown leaping forward, as in versions of this subject by other artists . . . rather, the short front legs have collapsed beneath the animal.”[5]

Paul Manship

The American sculptor Paul Manship is considered by many to be the greatest Art Deco sculptor of all, best remembered for his enormous 1934 Prometheus in Rockefeller Center, the most well-known Art Deco sculpture in the world.[6] As a style, Art Deco relates to the 1925 Exposition Internationale des Art Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes in Paris, though the term was coined in the 1960s by curators and art dealers. It is characterized by clean, streamlined, geometric forms with much stylization or conventionalization. Manship’s sculptures from the 1910s, such as his Indian Hunter and accompanying sculpture Pronghorn Antelope of 1914, are already very much in the Art Deco style.

After becoming the assistant of noted American sculptor Solon Borglum in New York City, Manship won the Prix de Rome in 1909, which enabled him to spend three years at the American Academy in Rome. Returning to New York in 1912, he gradually developed his quintessential Art Deco style. Manship moved to Paris in 1921 and set up a studio where the French painter of decorative themes Jean Dupas had worked. One of Manship’s most iconic Art Deco sculptures is his 1924 Europa and the Bull (fig. 7). This bronze sculpture displays the sensuality that was lacking in Milles’s version. The partially clad Europa embraces the reclining bull. But here she is kneeling in front of him, not on top of him, as in the Milles work. The exposed tongue of the bull may represent the subtle influence of the Milles version.

Although Manship usually worked in bronze, he occasionally sculpted in terra cotta, and in 1928 he created a ceramic version of Europa for the Cowan Pottery in Rocky River, Ohio (fig. 8). This figure of Europa apparently came from one of the same molds used for his bronze version. Manship met ceramist Guy Cowan at the Exposition of Art in Trade at Macy’s in New York, where there was a substantial amount of Cowan pottery on display.[7] Europa is the only known Manship design created for the Cowan Pottery, and the example in its museum might be the sole extant version.

Waylande Gregory

Guy Cowan was one of the leading figures in American ceramics.[8] His family had been in the pottery business for generations and he was one of the first graduates of Alfred, the New York School of Clay Working and Ceramics. In 1913 he opened the Cleveland Tile and Pottery Company, which he closed in 1917 to enter the service in World War I. In 1919 he established a pottery at Rocky River near Cleveland, naming it the Cowan Pottery Studio. Starting in 1925 he produced limited-edition ceramic sculptures that were exhibited in fine art venues, such as the annual exhibitions presented by the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia.

Waylande Gregory was Cowan’s leading sculptor and designer, arriving in 1928 to become the company’s only full-time employee.[9] Born in Kansas in 1905, Gregory had been the assistant of Chicago sculptor Lorado Taft, who was noted for his contributions to the World’s Columbian Exposition in 1893. While at Cowan, Gregory designed some of its finest ceramic sculptures, including Salome (1928), Nautch Dancer (1930), and Burlesque Dancer (1930). The Cowan Pottery closed at the end of 1931 due to financial problems stemming from the Great Depression. Gregory immediately started teaching at Cranbrook in early 1932, as a resident artist, and he developed the ceramics program there. Although Gregory’s arrival was greeted at Cranbrook with great expectation, he was not treated as grandly as Milles had been. Gregory had a full-time job at Cowan, but the situation at Cranbrook was very different. After negotiating his residency with Cranbrook’s resident architect Eliel Saarinen, Gregory seemed to be communicating more with George Booth, Cranbrook’s benefactor, once he arrived.

Setting up a ceramics program proved to be very expensive, costing $2,500. Gregory hired a contractor to build a kiln. This kiln gave Gregory an opportunity to create much larger pieces than he had at Cowan (up to 30 inches high). He also acquired a low-temperature kiln for smaller sculptures. However, Gregory did not want to understand that Booth expected to be compensated for the investment, which he viewed as a loan. At Cranbrook, Gregory and his wife were provided with complimentary lodgings, but all other income had to come from the sale of artworks and from teaching students on his own. The fee for the spring 1932 term, which included twelve two-hour classes, was $35, and he advertised his classes with elegant brochures printed at the Cranbrook shop (fig. 9). Because he was charismatic, he had a following of students, but since he was at Cranbrook for only about eighteen months, he did not have enough time to develop many followers in the field of ceramics. (The exception was Howard Whalen, who was his assistant at Cranbrook and who later opened his own pottery in California.)

In January 1933 Gregory renegotiated his contract at Cranbrook but not without listing several complaints. He found Cranbrook far removed from cultural centers, making it difficult to meet clients there and harder to find new students. And he was furious that when Raymond Hood, the chief designer of New York City’s Art Deco skyscrapers and a possible business connection, visited Saarinen, Saarinen failed to make an introduction.[10] It seems that mounting tensions between Gregory and the administration at Cranbrook may have been fueled by jealousy on the part of Milles, since Gregory’s career was certainly on the rise. In fact, in a 1968 interview, Finnish-born Maija Grotell, who would later replace Gregory at Cranbrook as resident ceramic artist, recalled, “And everyone said to me, ‘Do not speak to Carl [Milles] about ceramic sculpture. Don’t dare speak to him about it.’”[11] Although Milles sculpted in bronze and Gregory in clay, Grotell’s odd comment suggests a professional rivalry between the two. It is interesting that Gregory’s replacement as Cranbrook’s resident ceramist was a vessel maker, not a ceramic sculptor who might compete with Milles.

By March 1933 there was obvious friction mounting between Gregory and the Cranbrook management team of Booth, Saarinen, and Richard Raesman, the executive secretary. Hostilities exploded on March 4, a national bank holiday. Because the students were away and the Depression was still in full swing, Booth decided to close the Craft Shops and turn off the electricity and heat to save money. Gregory, who had a kiln loaded with major work, turned the electricity back on. While the sculptures were being fired, Booth had the electricity turned off again, damaging most of the pieces left in the kiln, including Gregory’s Europa and the Bull. Gregory left Cranbrook in June without making peace. Gregory sued Booth, but the settlement, which came two years later, turned out to be a wash, as the value of Gregory’s destroyed sculptures were balanced against the money he owed Booth for the two kilns, which he had never attempted to pay back.

Gregory re-created the destroyed Europa and the Bull (fig. 10), which was exhibited at his one-man exhibition at the Montclair Museum in 1934.[12] It was purchased in December 1941 by the Syracuse Museum of Art. As Gregory described it, “the sculpture is planned to be partially glazed in the natural texture of the clay. This brings about a splendid play of contrasts in the form of synthesis, texture contrasts and color relation.”[13] The piece seems to be the most classically Art Deco version in ceramics. Although the kneeling Europa is on the back of the bull, as in the Milles version (see fig. 6), the sculpture overall shows the influence of Manship’s second version of Europa and the Bull, Flight of Europa, of 1925 (Smithsonian American Art Museum), in which the belly of the bull is supported by dolphins. In Gregory’s version, the bull is supported by waves. Gregory was much enamored of Manship’s sculpture, and the two became friends within a few years. After Manship’s death, Gregory wrote about the influence of ancient art on Manship’s sculpture: “It was the exposure at first hand of the glories of ancient Hellenistic and Roman sculptures which started the crystallization of this style [Art Deco].”[14]

Valerie Wieselthier

A major shift in depictions of Europa in the United States occurred following the introduction of the more playful style of Vally Wieselthier, especially after she visited Cleveland in 1929 and influenced young American ceramists such as Viktor Schreckengost and Russell Aitken. Changes regarding the Jewish population in Austria no doubt encouraged her to move to the United States. Gregory’s classically Art Deco depiction of Europa became replaced by depictions that were much more whimsical.

Vally Wieselthier was born in Vienna in 1895 to a prosperous Jewish family.[15] Her father was an attorney of the imperial court, which enabled the family to have a lifestyle of luxury, complete with servants and nannies. She studied at the Kunstgewerbeschule (College of Applied Arts) with the well-known ceramist Michael Powolny from 1914 to 1920. The school, founded by Josef Hoffmann and Koloman Moser, was much associated with the Wiener Werkstätte (Vienna Workshops), which dominated the culture of Vienna at this time. Wieselthier spent her student days during World War I in relative security as a student. Thereafter, she became a leading member of the Wiener Werkstätte and one of the leading ceramic artists in Europe. In 1922 she opened her own studio, where she employed a number of people. She exhibited several works in the Austrian Pavilion at the 1925 Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs in Paris. Encouraged by the popularity of the Paris exposition, the Federation of American Artists organized “The International Exhibition of Ceramic Art,” which opened at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1928. This traveling exhibition spread knowledge of the current trends in European ceramics to other American cities.

Although Christian citizens in Vienna had, for the most part, accepted longtime Jewish residents, attitudes changed with the influx of approximately twenty-five thousand Orthodox Jews after the outbreak of World War I. Many of the refugees suffered in abject poverty because Christian factory owners refused to hire them. According to Ruth Beckermann, “While the Germans were condemning the Jews in the east to forced labor, the Austrians were condemning them to forced unemployment.”[16] The rise of anti-Semitism led to the first major Nazi attack on Jews in Vienna with the destruction of the well-known Café Produktenbörse in December 1929.

Wieselthier was invited to visit Cleveland when the Metropolitan’s exhibition traveled to the Cleveland Museum in February and March 1929. The exhibition’s Viennese ceramics had the greatest impact, especially the five examples by Wieselthier. Guy Cowan attended the exhibition with one of his best students from the Cleveland School of Art, the young Viktor Schreckengost. It is also likely that while staying in Cleveland, Wieselthier first became acquainted with Waylande Gregory, the head designer at the Cowan Pottery. Wieselthier brought a distinct Viennese style and sophistication to America. Marianne Horman has described her:

She undoubtedly personified the modern woman that emerged in the 20’s, self-confident, provocative and fashionably styled. She dressed in the style of the modern woman, wore her hair short, preferred figure-hugging, low-cut dresses, bold hats, striking jewelry and was always seen with a cigarette, the symbol of the emancipated woman.[17]

Wieselthier’s last stay in Vienna was from September 9 to November 23, 1931. The growing anti-Semitism in Europe may have become too much for her, and she established residence in New York. There was also a growing antagonism to modern styles, as evidenced by the Wiener Werkstätte’s bankruptcy and closure in 1932. In the same year, she took up residence with her fiancé, Paul Lester Wiener, sharing an apartment at 509 Madison Avenue; after they separated, she moved to 301 East 38th Street. Wieselthier’s Europa and the Bull (1938); (fig. 11) is markedly different from the others discussed. Her Europa, blond and nude, straddles the bull’s shoulders and rests her head on his, with her arms wrapped around his horns and her toes curled around the front of his neck. Only the bust of the bull is included, with his eyes rolling up in ecstasy and his red tongue hanging out. The scene conveys her affection and innocence and the bull’s carnal desire.

Wieselthier would later visit Gregory and his wife in Warren, New Jersey, a short commute. When she developed cancer, Wieselthier began to spend more time at the Gregorys’ home. She worked at her studio at 24 East 8th Street during the week but was afraid to take much medication then, fearing that the drugs would interfere with her responsibilities or with the quality of her work; she was financially stressed and needed to keep working. So on long weekends, she would take morphine while staying with the Gregorys, and could relax. She was very interested in Gregory’s monumental ceramic sculpture and she could speak in German to his wife, Yolande, who was Austrian-Hungarian. The Gregorys would take her to see points of local interest and to local events. In time, she became quite familiar with people in the area. She died in 1945.

Viktor Schreckengost

The Viennese ceramics that were part of the international ceramics exhibition in 1929, particularly the work of Michael Powolny, had great impact in Cleveland and were inspirational for Ohio-born Viktor Schreckengost.[18] He had been attending the Cleveland Institute of Art, studying ceramics with Guy Cowan. Another important and influential art teacher was Julius Mihalik, who encouraged him to study in Vienna. Mihalik, who had taught at the Kunstgewerbeschule, wrote a letter of introduction, and Schreckengost arrived there in 1930 for a year’s study with Powolny, Josef Hoffmann, and others. (Powolny had also been Wieselthier’s principal ceramics professor.) The humorous quality of Schreckengost’s later ceramic sculpture is a testament to the Viennese legacy, but he went beyond his training to develop his own focus and personal style. On Easter break he traveled to Russia; he may have been witness to the social and political changes that were beginning to rock Vienna and elsewhere in Europe.

Schreckengost returned to Cleveland and began working part-time at the Cowan Pottery—in fact, he was the very last artist to be hired there. Although the enterprise had filed for bankruptcy late in 1929, it was allowed to operate, maintain some of its staff, and fill orders until it closed its doors permanently in 1931. It was during these troubled times that Schreckengost created the Jazz Punchbowl, a limited edition that was originally designed for Eleanor Roosevelt. These bowls, decorated with skyscrapers, cocktail shakers, and ocean liners, are the most popular works to come from the pottery and may be among the most significant ceramic vessels produced in America.

During the later 1930s Schreckengost produced a series of ceramic sculptures depicting African-Americans. One of the best in the series is The Abduction (fig. 12), which shows a nude Europa reclining languidly on the back of the bull. No water or dolphins support the bull, however, as in the Europas by Gregory (see fig. 10) and Manship. Rather, the figures are accompanied by two African-American winged putti representing love. This Europa wears a bandanna, a common accessory among southern African-American and Caribbean women. Schreckengost modeled this Europa in the likeness of American entertainer Josephine Baker, who created an international sensation when she performed her Danse sauvage wearing only a string of artificial bananas and whom the artist had seen perform in Paris.[19] As the situation in Europe was becoming increasingly worse, it seems significant that Europa was becoming Americanized. This was one of three sculptures by Schreckengost to be awarded first prize in ceramic sculpture in the Syracuse Museum of Art’s 1938 Ceramic National Exhibition.

Russell Aitken

The humorous but sophisticated influence of Viennese wit is even more evident in the work of Russell Aitken, who had also been a student of ceramics of Guy Cowan at the Cleveland Institute of Art. After graduating in 1931 he found that the Cowan Pottery had closed, but he was able to decorate some of the remaining Cowan blanks, which were later fired at the Cleveland Institute. In October 1932 Aitken arrived in Vienna to study with Michael Powolny at the Kunstgewerbeschule. The Wiener Werkstätte had already closed by his arrival, and he must have seen an even more drastic scene in Vienna than had Schreckengost. Abruptly concluding his studies at the Kunstgewerbeschule as early as January 15, 1933, for no apparent reason, Aitken never received a certificate for his studies there. Nevertheless, he traveled to Germany and Hungary. Being an accomplished athlete and sportsman, he rode horseback, went canoeing, and even joined the Corps Hilaritas Wien, a Viennese dueling society. Social and political issues were generally not part of his work.

After he returned from Europe, Aitken joined a group of others and set up a cooperative venture in Cleveland known as the Pottery Workshop. Aitken created work there and gave instruction in pottery making. He moved on after a couple of years to White Sulphur Springs, West Virginia, where he continued to give instruction in ceramics. By 1935 he had opened a studio in New York City. His ceramic sculptures were represented in the Harry Salpeter, Sloane, Ferargil, and Brownell-Lamberton galleries, also in New York City. His best-known work, Futility of a Well-Ordered Life (1935), was based on Salvador Dalí’s Portrait of Gala with Two Lamb Chops Balanced on Her Shoulder (1933), now in the Fundación Gala Salvador Dalí, Figueras, Spain. Futility of a Well-Ordered Life entered the collection of the Museum of Modern Art, and although the museum played only a tangential role in the development of ceramic sculpture in the thirties, it made a rare exception in acquiring this work.

Aitken’s first Europa (fig. 13) was described in Time magazine as a “jolly maiden atop a jolly, ogling bull.”[20] It was included in the Cleveland Museum’s 1935 “May Show,” where it received a special award, and also won an honorable mention at the Syracuse Museum of Art’s 1936 Ceramic National. Its current location is unknown.

Aitken’s later Wyoming Europa (see fig. 1) is a more detailed and complex work. Like Schreckengost’s The Abduction, this Europa-as-cowgirl is concertedly Americanized. Aitken created several works relating to the American West and was particularly interested in the sculpture of Frederic Remington. When he was a student at the Cleveland Institute of Art, Aitken was close friends with Hughlette Wheeler, a teacher of sculpture who had been a cowboy, and Aitken himself had worked as a cowboy in Arizona and Montana.[21] He ceased creating ceramics in the 1940s, and his ceramic work is rare today. He was a well-known sportsman and philanthropist and put together significant collections of decoys and tribal art.

Charles Yerkes Dusenbury

Charles “Chuck” Yerkes Dusenbury was born in Detroit in 1915 and graduated from Highland Park High School. He attended the Art Academy at Cranbrook for no credit during 1935–1936 as a scholarship student. In those years he studied drawing and painting with Zoltan Sepeshy. In 1937 he turned to sculpture and studied modeling with Marshall Fredericks, which gave him some grounding in sculpture before entering more advanced classes with Carl Milles in 1937 and 1938. From 1938 to 1939 he assisted Milles in his studio as a “technician.” In 1940 he became interested in ceramic sculpture and studied ceramics with Maija Grotell, the year he created his version of Europa and donated it to Cranbrook, where he would later teach in 1946 and 1947. He married Cranbrook’s master weaver, Marianne Strengell, in September 1940; they had two children but were divorced in 1948. Dusenbury was one of six people associated with Cranbrook who formed the Saarinen-Swanson Group, which produced a collection of modern furnishings for the middle class that debuted at Hudson’s Department Store in Detroit. Dusenbury died in 1999 in Tryon, North Carolina.

Dusenbury’s Europa and the Bull (fig. 14) is one of the most amusing. As a student at the Cranbrook Art Academy, Dusenbury had studied sculpture with Carl Milles in 1937–1938 and then studied ceramics with Grotell.[22] Although Grotell was a vessel maker, she allowed Dusenbury to create a ceramic takeoff on Milles’s Europa (see fig. 6), two versions of which were on display at Cranbrook. Dusenbury’s ungainly female sticks out her tongue at the seemingly bewildered bull. Although the awkward pose of both figures relates to Milles’s original design, the comic nature relates more to the Europas by Cleveland artists Viktor Schreckengost and Russell Aitken.

The entry of the United States into World War II at the end of 1941 seemed to bring comical interpretations of Europa to an end. So we have come full circle with Europa, from Milles’s version to Dusenbury’s version, both of which are at Cranbrook today. For each of the artists discussed in this article, their expressions of Europa were, and remain, major examples of their artistry in their careers.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The author would like to acknowledge those who helped obtain photography for this article, including photographer Randl Bye, Barbara Perry, Gene Schreckengost, Chris Kende, Nadine (“Dina”) Bluemel, Gregory Wittkopp, and Christine McNulty of Cranbrook; Leslie Cade of the Cleveland Museum of Art; Lauren Hansgen of the Cowan Pottery Museum, Rocky River Public Library; and Karen Convertino, Everson Museum of Art.

The seminal study that started a revival of interest in such artists as Aitken, Waylande Gregory, Viktor Schreckengost, and Vally Wieselthier is Ross Anderson and Barbara Perry, The Diversions of Keramos, American Clay Sculpture, 1925–1950, exh. cat. (Syracuse, N.Y.: Everson Museum of Art, 1983).

Francis Sejersted, The Age of Social Democracy: Norway and Sweden in the Twentieth Century (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2011).

For Milles, the most significant study is Meyric R. Rogers, Carl Milles: An Interpretation of His Work (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1940). See also Ann Jonsson, “D’un mythe à l’autre: L’ ‘Europe’ de Carl Milles et sa symbolique en Suède,” in D’Europe à l’Europe, II: Mythe et identité du XIXe siècle à nos jours. Actes du colloque tenu à Caen, Caesarodunum 33, ed. Rémy Poignault, Françoise Lecocq, and Odile Wattel de Croizant (Tours: Centre de Recherches A. Piganiol, 1999), pp. 157–62.

Joan Marter, “Sculpture and Painting,” in Design in America: The Cranbrook Vision, 1925–1950, exh. cat. (New York: Abrams, in association with the Detroit Institute of Arts and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1984), p. 243.

Ibid., pp. 245–46.

For Manship, see Edwin Murtha, Paul Manship (New York: Macmillan, 1957); and Harry Rand, Paul Manship, exh. cat. (Washington, D.C.: Published for the National Museum of American Art by the Smithsonian Institution Press, 1989).

Curator Lauren Hansgen of the Cowan Pottery Museum in Rocky River, Ohio, discussed the connection between Cowan and Manship in an email to the author, October 21, 2015. Manship was a guest speaker at the Exposition of Art in Trade held at Macy’s department store in New York City, May 2–7, 1927. Cowan Pottery had the largest ceramic exhibit. See Mark Bassett and Victoria Naumann, Cowan Pottery and the Cleveland School (Atglen, Pa.: Schiffer Publishing, 1997), pp. 118–19.

For an excellent study of Guy Cowan, see Bassett and Naumann, Cowan Pottery.

For Gregory, see Thomas C. Folk, Waylande Gregory: Art Deco Ceramics and the Atomic Impulse, exh. cat. (Richmond, Va.: University of Richmond Museums, 2013).

Letter from Richard Raesman to George Booth, January 18, 1933, regarding Gregory’s contract with Cranbrook, Cranbrook Archives. Hood and Saarinen apparently remained friends after the international architectural design competition for the Chicago Tribune’s new headquarters, which carried a $50,000 prize. More than 260 entries were submitted. Hood won the competition, and Saarinen’s design came in second place. I would like to thank Leslie Edwards, Cranbrook’s head archivist, for sharing pertinent correspondence regarding Waylande Gregory.

“Conversation with Maija Grotell at Cranbrook,” May 24, 1968, in Jeff Schlanger and Toshiko Takaezu, Maija Grotell: Works Which Grow from Belief (Goffstown, N.H.: Studio Potter Books, 1996), p. 63.

Gregory’s Europa and the Bull was displayed at the Everson Museum’s Ceramic National exhibition in 1938. Although the Everson Museum has dated this work to 1937, a photograph shows it in an exhibition at the Montclair Museum, “Ceramic Sculpture by Waylande Gregory,” in March 1934. The photograph is reproduced in Folk, Waylande Gregory, p. 60.

Waylande Gregory, cited in Anna W. Olmsted, “Art Chat: Gregory’s Europa New Accession at the Museum,” Post-Standard (Syracuse, N.Y.), December 29, 1941. Gregory Archive, Cowan Pottery Museum, Rocky River Public Library, Ohio.

Waylande Gregory, “Living with Art,” Daily Home News (New Brunswick, N.J.), October 23, 1966. Waylande Gregory Archive, Cowan Pottery Museum, Rocky River Public Library, Ohio.

For Wieselthier, see Marianne Hussl-Hörmann, Vally Wieselthier, 1895–1945: Vienna, Paris, New York: Ceramics, Sculpture, Design of the Twenties and Thirties (Vienna, Austria: Böhlau, 1999). After Wieselthier died, Gregory took plaster impressions of her hands that are now in a private collection. St. Etienne Gallery in New York City mounted a memorial retrospective exhibition three years after her death, in 1948. Although the opening date is unrecorded, it closed on January 27, 1948.

Ruth Beckermann, Die Mazzesinsel: Juden in der Wiener Leopoldstadt, 1918–1938 (Vienna, Austria: Löcker, 1984), pp. 16ff.

Ibid., p. 213.

For Schreckengost, see Henry Adams, Viktor Schreckengost and 20th-Century Design, exh. cat. (Cleveland, Ohio: Cleveland Museum of Art, 2000), and Adams, Viktor Schreckengost: An American Da Vinci (Windsor, Conn.: Tide Mark, 2006).

Adams, Schreckengost and Design, p. 58.

“Ceramics,” Time, October 18, 1937, Cleveland Museum Archives.

Aitken’s friendship with Hughlette Wheeler and his interest in Frederic Remington are discussed in Anderson and Perry, Diversions of Keramos, p. 78. Aitken even collected some of Remington’s bronze sculptures.

I would like to thank Leslie Edwards for sharing this information. See also Martin Eidelberg, “Ceramics,” in Design in America, pp. 222–23.