Edith Heath (1911–2005) at wheel, undated. (Edith Heath (1911–2005) at wheel, undated. Heath (Brian and Edith)/Heath Ceramics Collection, Environmental Design Archives, University of California, Berkeley, design archives@berkeley.edu)

Karen Karnes (1925–2016) at wheel, ca. 1952–1954. (Courtesy, UNC State Archives Raleigh; photo, Edward Dupuy.)

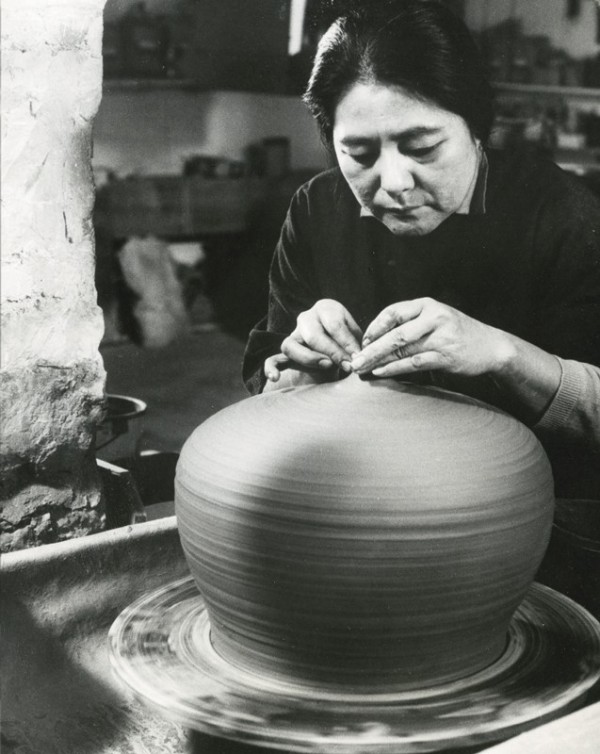

Toshiko Takaezu (1922–2011), ca. 1960. (Courtesy, American Craft Council.)

Johannes Vermeer (1632–1675), The Lacemaker, 1669/1670. Oil on canvas. 8" x 9". (Courtesy, Musée du Louvre, Paris, France; photo, Bridgeman Images.)

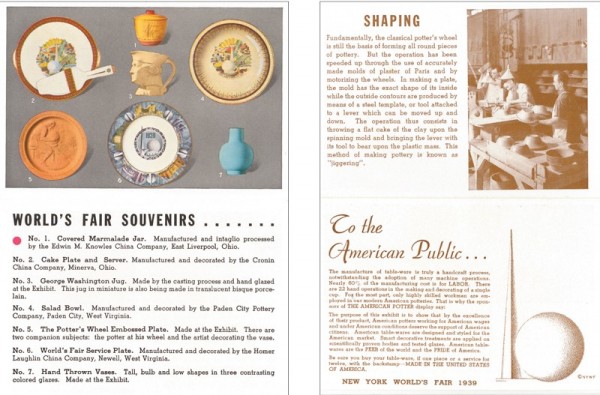

Brochure, New York World’s Fair, 1939. (Author’s collection.)

Edith Heath (1911–2005), Coupe (model cup), 1948. Glazed stoneware. H. 5". (Edith Heath (1911–2005), Coupe (model cup), 1948. Glazed stoneware. H. 5". Heath (Brian and Edith)/Heath Ceramics Collection, Environmental Design Archives, University of California, Berkeley, design archives@berkeley.edu)

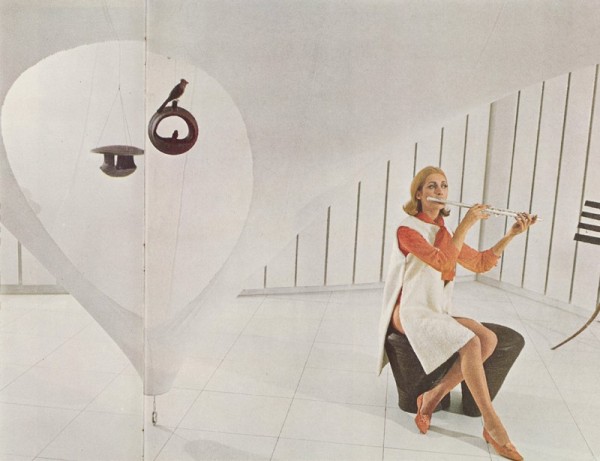

Demonstration of how the cup illustrated in fig. 6 can be held while smoking. (Photo, Caitlin Brown.)

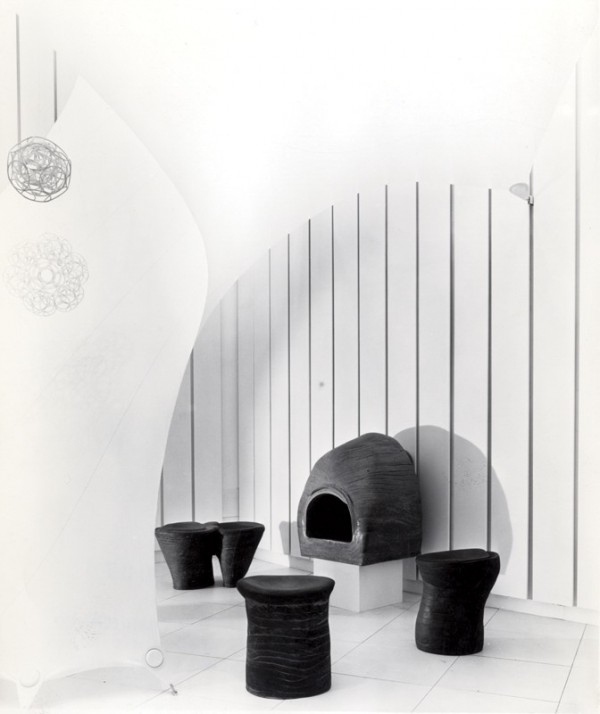

Karen Karnes (1925–2016), Stools, 1960–1967. Stoneware. Each 18" x 21 3/4" x 16 3/4". (Courtesy, Museum of Arts and Design, New York; photo, Ezra Shales.)

Toshiko Takaezu (1922–2011), Tamarind, ca. 1960. Stoneware. H. 35". (Collection of Peter Russo; photo, Brian Oglesbee.)

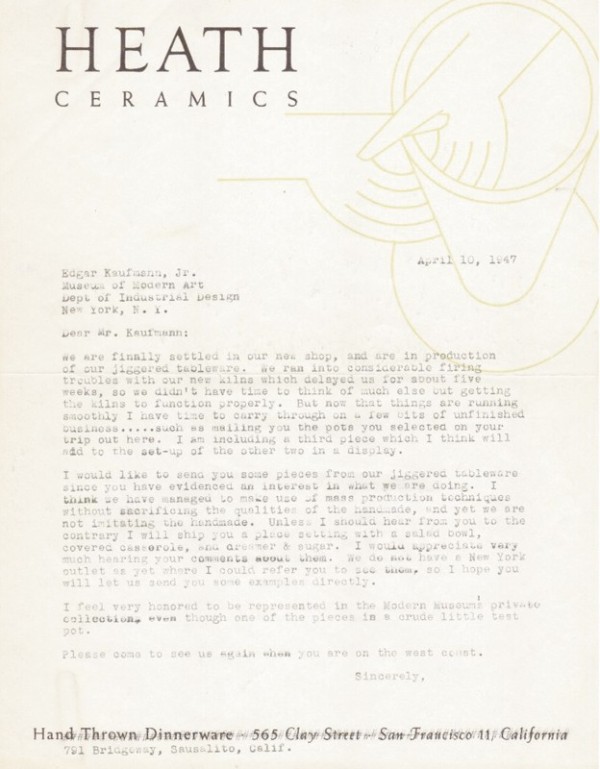

Edith Heath to Edgar Kaufmann jr., April 10, 1947. (Edith Heath to Edgar Kaufmann jr., April 10, 1947. Heath (Brian and Edith)/Heath Ceramics Collection, Environmental Design Archives, University of California, Berkeley, design archives@berkeley.edu)

Edith Heath, Marguerite Wildenhain, Lenore Tawney, and Toshiko Takaezu, June 1957. (Courtesy, American Craft Council.) The four artists are pictured at the First Annual National Conference of American Craftsmen, sponsored by the American Craftsmen’s Council and held at the Asilomar Conference Grounds, in Pacific Grove, California, June 12–14, 1957.

Karen Karnes (1925–2016), Double Vase with Candlestick Holders, 1951. Stoneware. H. 9 1/2", W. 13 7/8". (Courtesy, Everson Museum of Art, Lacoste Gallery.) The illustration is from Karnes’s submission to the 16th Ceramic National.

Detail of one of the stools illustrated in fig. 8. (Photo, Ezra Shales.)

Karen Karnes seating at Jack Larsen’s Round House. (Press photograph stamped and labeled New York Daily News, January 9, 1967; photographer unknown.)

Karen Karnes seating at Jack Larsen’s Round House, 2015. (Photo, Ezra Shales.)

Karen Karnes (1925–2016), ceramic seating and hearth, Milan Triennale, 1964. (Archive photo courtesy Biblioteca del Progetto.)

Karen Karnes (1925–2016), Double Seat (under model) and Bird Houses, Milan Triennale, 1964. Illustration in Saturday Evening Post, October 17, 1964.

Toshiko Takaezu (1922–2011), Nommo, Unas, Nephythys, Po Tolo (Dark Companion), and Isis (Sirius) from the Star series (fourteen works), 1999–2000. Glazed stoneware. H. ranging from 47" to 66". (Collection of the Racine Art Museum; gift of the artist; photo, Michael Tropea.)

If George Ohr (1857–1918) and Peter Voulkos (1924–2002) tend to be praised as artists—and not mere potters—because they “broke free” of conventional craftsmanship on the potter’s wheel by casting off function as a normative condition and rupturing classical form, why is it that no woman has ever inherited Ohr’s moniker, the “mad potter”? This deeply American narrative, a heroic liberation from European and Asian traditions, begs the question whether the “woman problem”—the lack of women in the studio craft canon—might be productively reconsidered by putting it in closer relation to the “wheel problem” and the question of what it means to be a pioneer in ceramics.

Generally, radical artistic license and aberrant tooling have been characterized as masculine discourses, whereas the maintenance of decorum is regarded as a feminine tendency and as effeminizing for men as the decorative. Three generations of critics have deployed the alliterative keywords violation, violence, and volcanic to position Voulkos as a centrifugal masculine force at the center of the mid-century revolution who transformed studio pottery into art. It is fine to claim Voulkos waged a battle against decorative art and traditional wheel-thrown art pottery, but it is time to suggest the ways in which a woman’s work made on a wheel was equally controversial and to outline ways that his female colleagues can be integrated into this narrative of modernist disruption.

In the 1950s and 1960s, successful women who were working in clay received such accolades as “delicate,” “lyrical,” and “intimate,” historically coded terms that facilitated the segregation and demotion of women’s contributions to modernism and visual arts in general, as art historians such as Linda Nochlin, Cheryl Buckley, and Pat Kirkham have eloquently demonstrated.[1] If, after 1969, this narrative broadened to include the first women ceramists who were acclaimed as radically uninhibited, they worked largely in a Pop and declaratively “fine art” mode, such as Patty Warashina (then Bauer) and Viola Frey. While Voulkos both accelerated and defiled the potter’s wheel in a Dionysian avant-garde explosion, did women’s work in clay constitute an alternative Apollonian tradition, or is there some less schematic way to include them in art history?

This essay specifically reevaluates the late 1940s to late 1960s work of Karen Karnes (1925–2016), Toshiko Takaezu (1922–2011), and Edith Heath (1911–2005) (figs. 1-3), and challenges where existing scholarship locates them in the margins of revolutionary ceramic art. Instead of positioning their contributions within the dominant art historical narrative that serves Voulkos’s legacy, can we contextualize them and their use of the wheel in new ways? Each of these three women exhibited nationally, and their pottery gained visibility through their successful participation in the Syracuse Museum of Art’s medium-specific national competition (“Ceramic National”) begun in 1932; each show traveled to numerous far-flung venues, including not just metropolitan areas such as New York City but also many small ones, until 1972. Yet these artists have never been written about critically as a threesome because even within ceramics they were considered to inhabit different modes of production—one in art, one in craft, and one in design. If their names were afloat in the ceramics scene, none crossed over to the fine-arts world as Voulkos’s did. He accomplished that momentarily, when he had a solo exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in 1960.

While many outside the ceramics field remain unaware of Voulkos even today, in Rose Slivka’s semi-erotic description of his muscular athleticism, through Christopher Knight’s reviews in the Los Angeles Times in the 1990s, and on to recent scholarship, a hagiography has developed within the subgenre of ceramic art history. Critical appraisals have celebrated his virility and established the story that ceramics needed to depart from the traditional uses of the wheel in order to become sculpture. Indeed, a 2015 exhibition at the Yale University Art Gallery, “The Ceramic Presence in Modern Art,” reiterates Voulkos’s centrality and includes an essay on George Ohr as his primary antecedent, despite his rediscovery occurring at a later date. Yale reaffirms Rose Slivka’s 1964 view on how and when clay turns into modern art—by spurning function and tradition—and positions a few women as mere adjuncts, none as Voulkos’s equal.

A simple Google image search of “Voulkos potter’s wheel” brings up evidence of manly potting across several decades, proving that he never abandoned the wheel as a theatrical stage to be bare-chested. Yet few women have been photographed working the wheel in such dramatic and combative terms. The one reference in the corpus of scholarship that does contextualize Voulkos in reference to the power of a woman artist is a comment by Frances Senska, Voulkos’s teacher at Montana State: “Sometimes, when you watch Pete throw, you can see Marguerite Wildenhain.”[2] With this inversion in mind, it is worth wondering whether the technique of the potter’s wheel is valuable as a place to revisit the assignation of gender roles, and reconsider where and when manual transgression comes into play. If ceramics was a workspace to attack decorum—get muddy and existentialist—it was still a place where women were generally depicted maintaining propriety. The uncanny was possible to attain in functional pottery, but not equally accessed: products by Heath, Karnes, and Takaezu might be valuable to suggest where, when, and how American women did break new ground, and to see the wheel in a new light. And a longer view of the wheel might generate a more eccentrically shaped history that is less reductively modernist and less of a reaffirmation of current art-market values, a major pitfall of much art historical enterprise.

By highlighting the distinct ways that each of these three women used the potter’s wheel, I hope to suggest an art historical framework conducive to evaluating both tableware and the more self-consciously fine-art ceramics. I propose that women working in clay might have left “quietly subversive” legacies worth adding to our canon, especially if craft and design are to be considered as representative of a zeitgeist as fine art. By resituating ceramic artistic production within the antipodes of license and decorum, instead of the avant-garde and its opposites, the academic and conservative, a more synthetic history that goes beyond the trope of individual genius or radical insurgency will emerge. Were women working in clay as reserved and conservative as scholarship suggests, or did they generate alternative modernities?

When they are revered today, Edith Heath is cast as California “good design” worthy of display in any museum of modern art, Karen Karnes is celebrated as a virtuosic and humble production potter, and Toshiko Takaezu is praised for achieving a Zen grace in ceramic sculpture, but this essay will set them into orbit around the potter’s wheel in order to see both the tool and their work in a common cultural context. Such a Venn diagram of art, craft, and design will emphasize their disciplinary differences in an attempt to reveal the breadth of women’s endeavors in ceramics. In 1969–1970’s Objects: USA catalog and touring exhibition no work by male artists (even Rudy Staffel or Richard Devore) is described as “delicate,” whereas both Karnes and Takaezu are characterized in this manner. Might we see these potters in a more complex light and offer their work a more nuanced reading today, perhaps as each testing the boundaries of gentility?

Photographic portraits of these three women aid an appreciation of potting as quietly content labor, a busying of hands that updates Vermeer’s Lacemaker in the suggestion of a total absence of thinking or intellectual labor (fig. 4). Rapt attention to the hump of clay on their wheel diminishes a sense of the activity’s athleticism. Surely, Heath, Karnes, and Takaezu appear to be centered, nonthreatening, and peaceful. The lack of eye contact with the potters in these images seems to reenact social codes of feminine modesty; these are not women who offer brazen glares. Peter Dormer used Vermeer’s image to question whether “the essential quality of craft activity [is] the pleasure of losing oneself in a practice activity.”[3] Certainly the wheelwork seems to subdue or at least displace an individual’s autonomy. The image displeased Dormer for its alignment of handicraft with cultural conservation, but was one he sanctioned to claim that craft is a peculiarly domestic affair. M. C. Richards would probably have approved of these images of potting as a representation of Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s notion of achieving “flow” and harmony in work.[4] There is no singular interpretation; one can see these images of handicraft both as an existential challenge in which individuals demonstrate self-reliance and as modernization vigorously contravened. We like to think of potting as hazy, romantic primitivism, a mythical lifeway, but the tool is mechanical as well. Sustaining the perspectives of both Dormer and Richards is my aim: Can we go beyond appreciating these women potters as modern variants on Vermeer’s Lacemaker? Did they occupy such assigned gender roles, or did they make unruly forms and depart from conventions despite portraiture that suggests otherwise?

The Wheel as Machine

To think of wheel-thrown pottery as disruptive is to move in the opposite direction from regarding the activity as spiritually “centering,” to use the title of Richards’s wildly influential book of that name, Centering in Pottery, Poetry, and the Person (1964). Richards’s view—that the wheel is a therapeutically transformative tool, a means to engage in Zen-like individual meditation—is now commonplace. Yet the potter’s wheel did not hold only one meaning in the early and mid-twentieth century; it was a symbolic tool used to serve numerous interests. For Voulkos it was about speeding life up, exploring life out of balance; for Richards the wheel is often seen as a place of refuge and solace, where the world slows down.

Problematically, the term potter’s wheel is remarkably vague and refers to numerous types of tools. Some are rudimentary kick wheels, others variable-speed electrified motors. In his hyperbolic praise for Voulkos as an innovator, Andrew Perchuk has written, somewhat misleadingly, “the archetypal potter’s tool—the wheel—was largely unknown for much of the twentieth century, and throwing on the wheel became widespread only in the late 1940s.”[5] Yet I argue that the identity of the wheel was not so clear-cut nor its florescence so acute, either in the 1940s or the 1970s. Voulkos was part of a wave of enthusiasm for electrifying the wheel, which remains the most plentiful type today, but this was not the “archetypal” wheel. Foot-powered wheels enjoyed resurgence in the decade after Centering was published. In the 1970s, to use a treadle or a kick wheel was a considered countercultural move off the grid—toward some presumed more historical and vernacular type. But many diligent art students in the 1930s used treadle wheels, and several classrooms and studios had wheels in motion when Voulkos was spinning his, though few were as powerfully motorized. Even if Richards centered on a kick wheel, and convinced many readers that it was the perfect metaphor to slow down, the majority of her readers in the 1970s probably used electric wheels. If “centering” was Richards’s image to help her readers achieve balance in a manner opposed to modern industrial society, the wheel remained fundamentally mechanical—about standardized rotation—and a strange metaphor to identify with organic life.

How did we come to talk about the potter’s wheel as if it were an ancient and unchanging tool? Perhaps through the use of nineteenth-century metaphors that set the device almost in opposition to the machine. Jiggering plates with profiles and casting in plaster were eighteenth-century techniques that cut into production achieved using the wheel, and steam power and the scale of production grew exponentially in ceramic manufacturing in the nineteenth century. In Robert Browning’s wildly popular poem Rabbi Ben Ezra (1864) the reader is asked to “note that Potter’s wheel, / That metaphor! and feel / Why time spins fast. . . .” Indeed, Browning urges his reader to reflect on “God, whose wheel the pitcher shaped” in contrast to “machinery just meant / To give thy soul its bent.” Similarly, the sense of the wheel as a source of universal cultural continuity is the tone of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s Kéramos (1878), which surveys an immense temporal span of cultures with the potter’s wheel as a constant life force—and concludes, as Browning’s poem does, that only “Potter and clay endure.” Kéramos naturalizes the wheel by setting the solitary potter under the shade of a hawthorn tree, a seductive and alluring vision, but alas—this solitary condition was likely first realized in the twentieth century. Potters at such idyllic pastoral encampments as Black Mountain College and communes like Marguerite Wildenhain’s Pond Farm in northern California turned Longfellow’s romantic poetry into a playbook.

Meanwhile, throwing pottery on a wheel in industrial production endured into the twentieth century, far longer than many expected. But factory conditions were never solo affairs for the potter. The “great wheels” used in ceramic manufacturing in the eighteenth century, such as at Josiah Spode’s, were dependent on divided labor: one operative was dedicated to produce power and another manipulated clay. In the mid- and late nineteenth century, the factory wheels gained new energy sources, as belts harnessed water, and then steam power. In small factories, such as Colorado Springs’s Van Briggle Pottery, professional throwers like Harry Bangs squeezed out hundreds of pots a day on the wheel, rows of pitchers that were standardized by the regularity of the clay as much as the belt-driven steady speed and the use of measuring devices like calipers mounted directly to the wheel. Throwing remained economically viable much longer in industry than we assume. The phenomenon of the potter working independently as a start-to-finish production facility is a twentieth-century invention; even more recent is the association of a potter’s wheel with anti-industrial use.

The mechanical purpose of the wheel is to achieve a consistent speed to facilitate controlled form-giving. Ideally, the head, or upper wheel, on which the clay sits revolves at 60–100 rotations per minute. Oscillation or eccentric movement of wheels results in disfigured pottery. Wheels that are foot-propelled relay this momentum to the platform above, but there are many kinds. In double-wheels or kick wheels, a flywheel set on a bearing sustains momentum and transfers the centrifugal rotation via an axle to the head.

To challenge the notion of an archetypal potter’s wheel, a closer look at mid-century Californian knowledge exchange is instructive, and educator Susan Harnly Peterson’s oral history is especially enlightening. Hired in 1952 to teach at the University of Southern California, she was horrified to find that Glen Lukens, her predecessor, had treadle sewing machines serving as pottery wheels. She immediately sought a budget to replace them with kick wheels.[6] Those conditions were subpar compared with the facilities at Whittier Union High School, in suburban Los Angeles, where her classmate from Alfred University, Joan Jockwig Pearson (later Watkins), was teaching at the time. There were also divergences in the design of the treadle wheel: a downward-moving pedal was common in the adapted sewing machines, while a horizontal bar lever was championed by many followers of Bernard Leach. This question of which wheel, the kick or the treadle, was superior would seesaw again in the 1990s, when the treadle grew in desirability for its perceived historical role in folk cultures. The irony is that the treadle wheel that so many Leachians used was actually one improved in the nineteenth-century Stoke-on-Trent factories, not a vernacular cultural product.

In order to understand the reinvention of the wheel by ceramic artists in the 1940s, it is worth noting that Peterson recalled attending Mills College in 1946 where F. Carlton Ball “had built a potter’s wheel from a picture in a German book of a treadle wheel.”[7] Ball and Glen Lukens, his teacher, constructed wheels from Singer sewing machine treadles, utilizing bearings from Ford Model A automobiles. Their efforts at the University of Southern California’s School of Architecture integrated pottery wheels into a broader university education.[8] Peterson had learned to throw pottery on a wheel when at Alfred, the New York State College of Ceramics, which prided itself on an encyclopedic curriculum of design, glaze, kiln, and clay technology.[9] At Alfred in the first decade of the twentieth century, Adelaide Alsop Robineau had been one of the first women to study the wheel and gain notoriety as breaking a gender barrier. It was only in the 1940s that women were using the wheel in sizable numbers in schools. In the 1940s, other role models included Marguerite Wildenhain, who, upon her arrival in the United States, built her own kick wheels. Gertrud Natzler had her kick wheel shipped from Vienna when she came to America in 1940, and attracted mature students such as Laura Andreson.[10]

In 2004 Peterson recalled with pride being an educator and innovator in wheel technology and how Peter Voulkos and Paul Soldner came to visit her when they were new to Los Angeles. They admired the variable-speed electric wheel that she and her husband, Jack Peterson, had built. Jack, who had also attended Alfred in ceramic engineering, held a position at Gladding, McBean, one of the largest firms on the West Coast specializing in architectural cladding.

We talked about wheels, we talked about the kilns . . . . [M]y husband had had Master Motor Company, which made gear reduction motors, hand-make a gear reduction motor for a low potter’s wheel that you could put hundreds of pounds of clay on. That’s just exactly what Voulkos needed. So he got the same motors and he built his own wheels with pipe legs and plywood.[11]

The earliest patent for a pedal-regulated variable-speed electric wheel dates to 1937, but the advancement took two decades to implement and was not commonplace until the 1970s.[12] Electric wheels had been demonstrated at the Golden Gate International Exposition in 1939–1940, but were not affordable or widespread for two decades. When use of the electrified potter’s wheel expanded with the rise in art programs, the variable-speed foot pedal control became a new convention, one that would prove second nature to a society already accustomed to accelerating their automobiles with a gas pedal.

Peterson’s memories of the four hundred small potteries around Los Angeles in the 1940s are also helpful in order to gain perspective on the diversity of approaches and numerous small firms—most of which press-molded and jiggered ware but some of which did use the wheel. To pay closer attention to the historical context, one should note that in department-store demonstrations, the potter’s wheel sold artistic goods and affirmed American independence from Europe since the 1920s. From 1915 to 1925, the Fulper Pottery’s John Kunsman was a regular sight manning a potter’s wheel at Bamberger’s department store in Newark, New Jersey, using the treadle-powered type of wheel that Peterson considered unpalatable.[13] Advertisements in the 1920s and 1930s attest that several American companies sold art pottery as an “inexpensive rare gift,” emphasizing that “every piece [was] shaped by hand”—on the wheel—and “not moulded by machine.” This encouraged the misrepresentation of the potter’s wheel as a tool that was not mechanical. The Fulper Pottery’s emblem was a round vignette that merged the profile of a wheel, vase, and thrower, and unified these elements with speed lines that radiated from the clay to the worker’s smock. Such a celebration of handiwork was also undertaken in the retail world on the West Coast, especially in stores such as Gump’s in San Francisco, where the pottery of Marguerite Wildenhain and Edith Heath was first sold in the United States, and which even sponsored an award in the Syracuse Museum’s annual ceramic national exhibition for “best designed pottery suitable for mass production” with the understanding that wheel-thrown pottery was still suitable for research and development for the mass-production of molded wares.[14]

The potter’s wheel was also a spectacle in the 1939 New York World’s Fair, when “Hand Thrown Vases” were sold at the pavilion sponsored jointly by labor unions and modern companies, among them the Homer Laughlin China Company (fig. 5). The display featured “modern” ways of making pottery—jiggering it and firing it in a continuous tunnel kiln, for example—but also spotlighted skill on the potter’s wheel. Judging from advertisements, fairly sedate monochrome vases were peddled alongside historicist knickknacks, but all were celebrated as “truly a handcraft process,” even jiggering. In addition to being an exhibitor at the World’s Fair, Californian F. Carlton Ball demonstrated his potter’s wheel alongside Maria Martinez making coiled ware, both situated within a spectacle purporting to envision the “World of Tomorrow.”[15]

To add one more perspective to the discourse of ceramic technology, in the first half of the twentieth century archaeologists argued over the development of the wheel in ancient America and Europe and its role as a measure of civilization. Otis Mason and other ethnographers speculated that pottery was historically women’s work, made by hand. The potter’s wheel was seen as a device that sped up society, leading to industrialization and standardization, and was overtly conceptualized as a mechanical innovation. Amateur potter and antiquarian Henry Chapman Mercer, founder of the Moravian Pottery in Doylestown, Pennsylvania, himself distinguished between using a wheel and making pottery “by hand”—that is, without a wheel—as if the revolutions of the tool reverberated cataclysmically, neatly cleaving temporal phases of human culture. In 1954 archaeologist V. Gordon Childe celebrated the potter’s wheel as a radical innovation that the Sumerians devised at the same time as the chariot wheel, noting that “a professional can shape in ten minutes a vessel that might take a housewife ten hours to build by hand.”[16] Just as the accuracy of Childe’s interpretation has been challenged, so too should we note his risible gendering of preindustrial and mechanical labor. Childe seems to have conceived of the “housewife” potter as either an indigenous “primitive” or a modern amateur. The modernization of pottery with the wheel was conceived as a masculine application of technology.

A saner voice in these discussions concerning the history of technology was that of anthropologist George M. Foster at the University of California, Berkeley, who challenged both the scholarship regarding the gendering of the wheel and ceramic production in general. Foster paid attention to the real complexity of pottery, accounting for trimming pottery after pots are thrown—which also used wheels. “Much ware can neither be classified as wheel-made nor hand-made, since various combinations of the two methods are used,” Foster concluded, dismissing assumptions about gendered as well as technological determinism.[17] Foster’s rebuttal of stereotypes might very well have had something to do with his location in the Bay Area, where Wildenhain, Heath, Laura Andreson, and Beatrice Wood were all visible as exhibiting potters.

To claim that the potter’s wheel signified either slow or fast production at mid-century is obviously a risky generalization, one as fraught as ascribing technological invention to one gender or another. By the time Richards’s Centering celebrated the potter’s wheel as a respite from industrialized mass culture, both popular and elite dispositions might have looked on the flywheel as a mechanical contrivance not worthy of respect as a machine; such interpretations depended on subjective opinion. In June 1957 at the First Annual National Conference of American Craftsmen held at the Asilomar conference facility in Pacific Grove, California, when Elena Netherby (a founder of the Mills College Ceramic Guild whose wheel-thrown pottery received citations of praise at the Syracuse Museum’s ceramic nationals in 1949, 1956, and 1957) sat beside Peter Voulkos, it is probable that he knew her as a woman who ran a contracting business building mid-century suburban ranch homes around San Francisco. She also had the distinction of filing a patent on a kick wheel, design #no. 61,363; Voulkos might have known that, too. He even might have used a Netherby wheel when he demonstrated for Laura Andreson’s students at UCLA or at Scripps.[18] And he was also probably aware that Jayne Van Alstyne, one of his teachers at Bozeman and one of Peterson’s colleagues at Alfred University, was interested in improving the kick wheel, and drafted blueprints for a “Dandy Potter’s Wheel” as carefully as she drew sketches for General Motors, where she worked as an industrial designer. More famous are the electric and kick wheels of Paul Soldner and Alfred University’s Ted Randall, which developed into lucrative businesses. Van Alstyne’s blueprint for a wheel shows that women such as herself and Peterson saw both the electric wheel and the kick wheel as living technologies, and ones that they had mastered but might still be worth improving. To be certain, the ambition to live as an artisanal potter in the shadow of the atomic bomb seems anything but rational, but it is a complex decision worth savoring in terms of these nuances of gender and the technological landscape.

Three Wheels Turning: Heath, Karnes, and Takaezu

The following three profiles expand on the complex ways that we conceive of clay in relationship to the technology of the wheel by looking more closely at both artistic work and lives. The work of Edith Heath importantly recenters the role of the wheel in design, mass production, and invention. Instead of seeing Heath ware as factory production that was boldly modern, Heath herself deserves to be regarded as locating handicraft in production and incorporating the wheel as a modern, even contemporary tool, from the 1940s through the 1970s. Her designs still are faithfully made, a remarkable seven-decade run. Her low-slung handle continues to seduce hipsters; it purportedly satisfied Heath’s desire for a handle that enabled her to accommodate both vices of drinking coffee and smoking a cigarette in one hand—a pose of daring informality (figs. 6, 7). This freed up her other hand to direct her factory.

Karen Karnes, recently reconsidered in the book A Chosen Path (2010), dedicated her life to pottery in conjunction with the wheel but also labored to challenge simple definitions of virtuosity and technique in ceramics, shifting out of her comfort zone repeatedly to experiment and expand her oeuvre.[19] Her coil-built stools are difficult to integrate adequately into her tableware and reflect her ability to think “beyond” the wheel in a manner as untraditional as Voulkos or any other twentieth-century ceramist (fig. 8). Like Voulkos, Karnes deserves to be interpreted as revealing the process of unlearning technique as much as the mastery of the wheel.

Of these three potters, Toshiko Takaezu was closest to Voulkos in friendship. Like him, she was trained as a potter first then decisively shifted her allegiance to the self-conscious production of fine art. Her work after 1960 used the wheel but disassociated thrown forms from functions, and she became famous for closing her vessels in on themselves (fig. 9). If any contemporary of Voulkos deserves to be seen as sympathetic to his upending of the wheel, it is Takaezu, but, curiously, she has never been seen as “unmaking” pottery or as veering toward his allusions to destruction. Rather, she has been interpreted in a most narrow vein, exoticized as a Hawaiian-Japanese-American and considered a landscape painter of sorts.

EDITH HEATH'S WHEEL: Central to Mass Production

Edith Kierzner Heath first gained exposure to ceramics at the Art Institute of Chicago in the mid-1930s, and by the end of the 1940s her tableware was considered to embody the new postwar California lifestyle. Her mix-and-match monochromatic forms, initially in a palette of four colors (sage green, blue, sand, and shining sand), celebrated coastal associations and continued the idea of a “distinctive informal dinner service” cultivated in the 1930s by the likes of Russel Wright (1904–1976) and Frederick Hurten Rhead (1880–1942). That she ran her own company for four decades and continued to throw prototypes on the wheel for all those years make Heath a remarkable pioneer of modern craft, and shows her to have been hands-on beyond the range of most other designers and entrepreneurs. She is said to have converted a treadle sewing machine into a potter’s wheel in order to maintain production once she graduated from art school, and then, in 1946, she used the pottery studio at the legendary boutique department store Gump’s to keep up with orders; she and her husband, Brian, opened their Sausalito factory the next year. Such anecdotes reveal the broader economic context in which studio pottery grew. Heath exhibited both locally, at the Legion of Honor and Merchandise Mart, and nationally, in Syracuse Museum annuals from 1946 through 1956. Unlike Karnes and Takaezu, who worked alone, Heath achieved all this through incorporation, joining forces with her husband and building a loyal and close family of skilled employees. For Heath, the kick wheel was not an escape from mechanization but a spring that fed production and the score of hands who were her team.[20]

The contexts in which Edith Heath exhibited reflect the choices that were open to her and which she cultivated: an ideal of art in everyday life and a belief in scaling production to need and want. She participated in exhibitions of interior design as well as the medium-specific shows organized by the Syracuse Museum. At Syracuse’s 11th Ceramic National Exhibition, in 1946, Heath showed bowls and a plate ranging in price from $15 to $35. Objects made by numerous peers using the wheel were also exhibited that year, among them Maija Grotell’s five large vases, priced considerably higher at $175–$275, and Laura Andreson’s $100 cookie jar. At the 12th Ceramic National Exhibition, in 1947, Heath exhibited a wine bottle and three cups, an eleven-piece tea set (the teapot with a silver handle by Franz Bergman was featured in LACMA’s recent “California Modern” exhibition), a vase and a turquoise matte bowl, all hand thrown. By the years of the 18th and 19th Ceramic National Exhibitions, 1954 and 1956, Heath was included in a special category, “Artists in Industry Exhibit,” alongside Glidden’s ram-pressed tableware and Viktor Schreckengost’s “Primitive” line for Salem China. By 1959 Heath’s production output, nearing a quarter million pieces a year, was made in a factory that she designed with Robert Marquis and Claude Stoller; a model of enlightened entrepreneurship, it provided each worker with a window. The factory is a wonder today for still running as it was envisioned then.

In between these benchmarks, a 1949 article in the New Yorker by Sheila Hibben praised the arrival of California tableware made by individuals and some medium-sized firms that employed a dozen to one hundred people, and singled out Heath. “She has managed to retain an astonishing feeling of spontaneity and freedom in her forms,” Hibben gushed, claiming the quality and design superior to the eccentricities of Eva Zeisel’s “Town and Country” made by Castleton.[21] The number of outlets for wheel-thrown ceramics at the time in Manhattan suggests the aftermath of World War II was a high-water mark for craft. One could shop for handicraft pottery at many small shops: New Design on 75th Street; Rabun Studios on Madison and 68th Street; Cardel on 58th Street; Jacques Seligmann, Rena Rosenthal, and Van Diemen-Lilienfeld Galleries on 57th Street; America House on 52nd Street; Americraft on 51st Street; and Cavallon Olds on 11th Street. Larger boutiques in such department stores as B. Altman & Co. and Wanamaker’s also carried these wares. Southern Highlanders maintained a store on 50th Street that carried Jugtown pottery from rural North Carolina, but Heath had buyers from Marshall Field & Co. of Chicago, Neiman-Marcus (later without the hyphen) of Dallas, and Bullock’s of Los Angeles. Her craftsmanship was not a touristic novelty but an aesthetic with large geographic distribution to a discerning constituency. Hibben’s article was followed three months later by a classified advertisement that suggests the stature of Heath’s company and the currency of her name: the rental of “the most completely equipped home in Fort Lauderdale” had Robsjohn Gibbings furniture and a “Kitchen completely equipped with everything electrical. Edith Heath dinnerware. Blenko glassware. No expense spared.”[22] Heath had become a known luxury brand signifying comfort in just a few years.

Correspondence in 1947 between Edith Heath and Edgar Kaufmann jr. (his preferred spelling), the curator at the Museum of Modern Art, and in 1949 with Edgar’s mother, Liliane (the buyer for Vendome Gifts, an exclusive shop in Kaufmann’s department store in Pittsburgh, owned by her husband), suggests that two years before Hibben’s glowing notice in the New Yorker the curator had seen value in Heath’s “Hand Thrown Tableware,” as it was identified on her letterhead (fig. 10). Not only was Kaufmann jr. collecting her prototypes and adding them to the museum’s collection, he seems to have alerted his mother to them as well.

Heath Ceramics stationery depicts a pair of stylized hands throwing a cylindrical jar, an image that lingered despite the fact that the company sold jiggered ware after relocating to Sausalito in 1947. The line drawing was an apt means to describe the company’s research and development as well as good branding. In 1964–1965, when Heath made prototypes for Wedgwood, she made them first on the wheel. It was not a technology to leave behind or graduate from, and remained in use as a tool in prototype design by firms such as Arabia in Helsinki, Royal Copenhagen, and several Staffordshire pot works for much of the twentieth century. Production might require jiggering and molding, but the wheel was still a place to feel one’s way into a form.

Despite Edith Heath’s acumen at the wheel and the success of her company, it is worth noting that Rob Forbes, founder of Design Within Reach and a graduate of Alfred University who was a thrower of wares for a decade, recently asked, “How is it that I wasn’t aware of Heath Ceramics, given that the company has been cranking out pottery since the 1940s in my own stomping grounds of Northern California?”[23] Although Edith Heath was invited to the First Annual National Conference of American Craftsmen in 1957 and hobnobbed with renowned potters such as Marguerite Wildenhain and Takaezu (fig. 11), her work was rarely valued as “handicraft” by the time Forbes trained in the 1970s—most potters regarded it as “design.” What counted as wheel-thrown work in art academies and craft fairs after 1970 was work that was strictly solo performance. Heath and her work were not taught to several generations of M. C. Richards acolytes, who were interested primarily in centering clay and self. As self-expression grew to be the prized value of wheel-thrown pottery, a general appreciation of the wheel as a tool to manipulate precision withered both pedagogically and aesthetically.

KAREN KARNES: Learning and Unlearning Technique

Although Karen Karnes was cast as a sculptor in the revisionist 2011 exhibition “Crafting Modernism,” originated by the Museum of Art and Design (MAD), New York, she has always described herself as a potter. Her work has always been firmly functional and titled as such. Back in 1951, before the art market heated up to today’s level, her peers Leza McVey and Peter Voulkos also called their work pottery and exhibited it as such. Understanding that Karnes’s and McVey’s radical hand-built clay forms were categorized as “pottery” and not “sculpture” in the 16th Ceramic National Exhibition of 1951 is difficult for many to accept and contradicts the prevailing twenty-first-century desire for definitive categorization. The Karnes and McVey pieces were classified as pottery alongside the much more traditional wheel-thrown work of Peter Voulkos. The same year, a vase by Karnes won a national prize sponsored by Lord & Taylor (fig. 12). A decade later Karnes won a Palma d’Oro in 1963 at the Milan Triennale for hand-built garden stools, and, in 1969–1970’s “Objects: USA” exhibition she represented herself with these stools made with a coil technique, though she again elected to call herself a “production potter.”

The relabeling of Double Vase in MAD’s 2011 “Crafting Modernism” show now negates the intended function of the piece, which originally was titled Double Vase with Candlestick Holders (1951). Photographic records in the Everson Museum show it in use, holding branches in one reservoir and a tall white candle in each of two others. In contrast to locating the work on a white pedestal in 2011, these archival images articulate Karnes’s intentions to set table: etiquette and social concerns are essential. What at first might appear to be surrealist biomorphic indentations on the pot’s top are explained away by the original title; they are for holding candles. The organization of the two cavities also becomes more clear: one sphere is intended to contain wabi-sabi clippings of weeds and the other kept as an access path to replenish water. These functional rationalizations discourage perceiving the vase as an abstract form. She made the vase in Sesto Fiorentino, Italy, while accompanying her second husband, David Weinrib, on his grant-funded travel. A cosmopolitan New Yorker, she knew museum collections well, and so one can credit the complexity of Double Vase with Candlestick Holders to an appreciation of what would have been labeled “primitive pottery” by her childhood haunts, the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Museum of Natural History. However, the compelling surface pattern of rhythmic incisions remains mysterious but impossible to label as derivative of any specific historical model. The incisions resemble both body scarification and linoleum block cuttings. In comparison, the Voulkos wheel-thrown pottery on display alongside Karnes’s piece was a “popcorn bowl” and a “decorative rice bottle”—a mélange of heartland Americana with Anglo-Japanesque folksiness.

Karnes purportedly had no experience with clay until she met Weinrib, despite having studied at Music & Art High School in Manhattan, where Lee Rosen, founder of the ceramic firm Design-Technics, taught pottery, and then at Brooklyn College with Serge Chermayeff. Meeting Weinrib while taking an evening course at the Newark School of Industrial Art, Karnes decided to flee her role as a suburban housewife and elope with Weinrib to live as a bohemian artist. She usually credits her first interest and work in clay to when she and Weinrib spent a summer living in a tent in East Stroudsburg, Pennsylvania, making ceramic lamp bases for Design-Technics. Weinrib connected to the firm through his colleague from Alfred, Nancy Wickham (later Boyd), who won a prize at the 11th Ceramic National Exhibition in 1946 for her $4.25 Design-Technics breakfast set. If Karnes did find pleasure and skill in hand-built clay forms that summer, when she finally enrolled at Alfred University she gained exposure to the wheel as a discipline. Herbert Cohen, a fellow New Yorker who won a scholarship from the Henry Street Settlement to study at Alfred at age sixteen, remembered watching her trim the foot of a pot in one of their classes and leaving it too thick—but was prevented from interfering by his shyness and modesty.[24] This memory is important in order to locate Karnes as a skilled painter and designer who then pushed herself in ceramics to become a good potter. She came to the material with a sophistication that would prevent her from being seduced by an ideal of virtuosic technique but did focus on the wheel as a skill worth pursuing. As befits a mature student who had confidence, Karnes could exploit elementary techniques.

Although she was more skilled on the wheel after her year at Alfred University and subsequent years throwing pottery at Black Mountain College, in the late 1950s Karnes gravitated to press-molded forms and also began to coil-build large freestanding sections of bird baths and planters. In an interview with Dido Smith in Craft Horizons, she described this decision as one made alongside her physiological transformation when she became pregnant.[25] She was profiled as a beatnik homesteading in a cooperative community, Gate Hill, on the Hudson River thirty-five miles north of New York City, asserting her freedom from mainstream society while remaining dependent on all of the urban forces of capitalism bustling downstream. She sold her casseroles on Park Avenue at Bonniers and her garden furniture to weekenders. The Swedish emporium favored unique and handmade pottery, shaggy flossa weavings, and tastefully sleek teak furniture by designers such as Jens Risom. Karnes’s teacups were tender and refined as well as texturally gritty in that context. She was not making mugs to swig from crudely but cups to sip from in genteel repose, to slow the world down. When Karnes situated herself just an hour outside the city, her admirers and patrons drove up the new Palisades Parkway to visit “the Land,” as Karnes, M. C. Richards, and experimental filmmaker Stan VanDerBeek called it. To put this socioeconomic dynamic in context, during the 1950s many in Gate Hill were dependent on urban commerce. Karnes’s neighbor John Cage was under contract with Jack Lenor Larsen, the weaver-entrepreneur, to design advertisements and Larsen Incorporated’s Christmas cards. Gate Hill’s many musicians performed in and around Manhattan.

Karnes began to make stools and chairs, usually in pairs, about 1957 or 1959. These heavy and squat ceramic forms at first glance resemble obstacles rather than seating. Like elephant-foot wastebaskets popular with big-game hunters, they evoke the unexpected even if they are decorative furnishings (fig. 13). This is not what Harold Rosenberg meant when he coined the phrase “the anxious object,” but the term is well suited. Part of the disturbing nature of Karnes’s stools and chairs is that in their scale and shape they call to mind associations with toilets. They are also precarious, narrower at the base and flaring outward. The color and girth of the brown coils increase our visual associations with human evacuation. Is the stool another type of stool? The anatomy of excrement and anthropomorphic forms of sanitary appliances seems playful.

As a building method, the coil is a fundamental manipulation of pliant stuff like dough or mud, to the degree that it is almost a preschooler’s exercise. However, Karnes elevates the coil by exaggerating and emphasizing its visibility. Her ability to preserve the plastic and viscous quality of the clay is both elegant and extremely difficult to achieve. The novice’s method of coiling clay becomes reinvented and complex in Karnes’s hands. Whereas the coiled sides rise in anatomical strata like geological intestines, the seat is smooth and taut like a piecrust. There is a contrast within the structure. On the one hand, the bucket seat seems to slope gently in a curvature that matches the human body, but on the other hand this seat is sliced open dramatically. The deliberate gap permits rainwater to drain out and yet also lends intentional mystery to the interior. By touching this topography, an admiring finger circumscribes the ceramic form to understand the process, after which the swelling shape seems less unnerving. One can sense the potter working in a centripetal manner around the hollow center and moving eccentrically to sustain an outward thrust. Karnes balanced making the walls lean out and keeping the clay from collapsing.

They might seem as if they are made to be outside, liberated from a white cube, where they might connect to rocks and leaves and resemble tree stumps, in both textural and literal manners, but Karnes made her stools and tables to go inside as well. The genre of the garden stool flourished in the postwar attitude and erased the distinction between patio and open living room, exterior and interior. Sliding glass doors and expanses of plate glass transformed mid-century domesticity and opened up new possibilities for informal living. Karnes’s birdbaths and planters also occupied these new liminal spaces of the “open floor plan” and migrated with the seasons; her stools fit this repertoire even if they only grudgingly welcome sitters.

Karnes made about a dozen stools and chairs, mostly pairs but one trio, and they were in important private collections. The most accessible to the public was a single seat in the Noguchi Museum in Queens, New York (a venue devoted to the artist and architect Isamu Noguchi), where for years it was the one work of sculpture displayed that the artist that himself had not made. Learning of Karnes’s work from Noguchi, Jack Lenor Larsen also commissioned work from Karnes, and when his African-inspired Round House opened in 1963 and received critical attention in dozens of national newspapers and periodicals, many noted that Karnes had contributed a fireplace, a pair of garden stools, sinks and tiles to the bathroom, light switch plates, and finials on the roof (figs. 14, 15). Locating Karnes’s stools in their appropriate environment is a challenge. There is no single place but rather myriad material forms, social acts, and emotional atmospheres; in the Round House the four stools could be considered tribal and “primitive” as well as delicate and down-to-earth. The seat looked austere and biomorphic among Noguchi’s sculpture. Karnes’s stools ended up in her own home alongside seating by Eames and Aalto, icons of modernism, and also beside overstuffed wing chairs upholstered in chintz. Does their roughness air reservations about submitting to authority or the predicament of conformity, or does it aspire to resemble an organic fungus? They sit quietly, repudiating formality.

The stools seem to have willpower; they are aggressive social objects. “Karen’s chair sits you, you don’t sit on it,” noted Zeb Schachtel, one of her oldest friends and a customer since the 1960s, who had three ceramic seats on the porch of her beach house. That Karnes embarked on making her seating just before her mother bought her an Eames Lounge Chair, a recently debuted design at the time, is suggestive. As in the Eames chair, one sits on a slope. Both spin upward on smaller bases. The chairs exude physicality, which looms as an integral part of their social function. Looking at them one can envision the diminutive Karnes heaving them up, almost equal to her own weight, as she moved the wet clay into form and into the kiln all by herself.

Whereas the Eames chair spun on its base, Karnes’s coiling compels the viewer to circumambulate, inverting the idea of centering and oscillation as social actions. Her large planters and birdbaths comprise alternative miniature intentional communities, little worlds complete in themselves. The stools, begun after she was left by Weinrib and had to manage as a single mother, seem resilient and antisocial even if they also demand people to complete them. Do the stools materialize companionship or its absence? One set of stools especially seems to visualize the ideal of coupling and also of cellular division—mitosis. Karnes noted that she needed Weinrib’s help to flip the clamshell-like halves of the largest planters onto pillows before joining them together; the stools posed a physical challenge. Her inquiry into making ceramic seating emerged specifically during this moment before or during their separation. She made large seating in suites of two and three after her marriage to Weinrib disintegrated in 1956, and ceased when she began her next long-term relationship, with Anne Stannard, another ceramic artist.

It is probably difficult for young artists today to understand why Karnes refrained from calling her ceramic work “sculpture,” and why she continued to throw casseroles on the wheel time and again over more than five decades. Her work could be seen as art, craft, or design today. Her garden stools at the Milan Triennale in 1964 were gathered around a hearth, alongside a hammock and a chair made by Eva Zeisel (figs. 16, 17). She was acknowledged with a Palma d’Oro, but there was very little interpretative analysis of the work. Were the stools a declaration of unlearning skill, in that they exploited coiling as a visual process, or were they merely picturesque? At the time of his exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in 1960, Voulkos’s work was acclaimed as “free ceramic sculpture” with an “interest in natural textures,” terms seemingly applicable to Karnes’s seats. Her stools have never before been regarded as overtly antidomestic in the same way, and this is the first appraisal to suggest they have elements of the uncanny. Even when the Karnes stools toured the nation in “Objects: USA” in 1969, they were singled out as “one or two of a kind,” not plumbed for meaning beyond their obvious function. In relation to the praise lavished on Karnes as a virtuoso on the potter’s wheel, these stools were incongruous, obstacles more than examples.

TOSHIKO TAKAEZU: Explicitly Thrown, Implicitly Fractured

When Toshiko Takaezu arrived at her mature style in the early 1960s, she signaled the shift by declaring that she made “ceramic forms” on the wheel, no longer mere bowls. She now squarely situated her pottery, once categorized by implied function, as art, using a new terminology. Her decision to reject the word “pottery” along with keeping the wheel as her central tool is one way to understand her proximity to Voulkos, her friend.[26] Although she is famous for making closed forms on the wheel that boldly refute function, Takaezu was not the first to arrive at that innovative strategy. Her gesture of closing her pots into spheres was not a violation of convention and her work has never been read as subversive. She was a teacher, quietly yet willfully driving the young elite of Princeton University to question their values and ponder her work’s validity. To pursue a more complete interpretation of Takaezu’s work and suggest alternative readings, this profile will emphasize her penchant for adding a rattle to the interior of her closed forms, an act that requires evaluating the pottery’s sound and touch and weighing these engagements with sensual knowledge as equal in priority to sight. It is through full sensorial engagement that Takaezu’s work ceases to be merely beautiful and inches closer to conveying more complex and contradictory messages. The sense of modernist rupture and fragmentation that is literal in Voulkos is also present in some of Takaezu’s works as a crack or fissure, but not the enduring mark. Her illusionistic layering of glazes and concentric form suggest completion, not disintegration.

Like Karnes at Alfred, Takaezu was a mature student by the time she landed at Cranbrook Academy of Art. Her journey to Cranbrook was sponsored by the Hawaiian department store, McInerny. Although her studies with Maija Grotell at Cranbrook constitute a visible legacy in her work through the 1950s, before that she studied at the Hawaii School of Art with Claude Horan, who had graduated from Ohio State University. Upon Takaezu’s graduation from Cranbrook in 1954, the Los Angeles Times ran a profile of her as a “Japanese Potter” and explained her pathway from the Potters’ Guild in Honolulu, where “she made commercial pottery by semi-mass-production methods” until, “[d]issatisfied, she began working in sculpture.”[27]

Takaezu began to call her work “art” instead of “pottery” between 1962 and 1965, the 22nd and 23rd Ceramic National Exhibitions; she announced that she was making abstractions, and that to make a work of art abstract was necessarily to depart from function. In her first appearance at the Ceramic National Exhibition, in 1962, Takaezu exhibited a large, dark purplish-black bowl; and in her second attendance at the prestigious show, in 1965, she presented an eight-inch-high pumpkin-shaped clay object titled Stoneware Form. Although the 1962 bowl had a lively glaze treatment, it was still very much a unified skin with a limited tonal range; the 1965 “form,” however, was mostly dipped in a dark glaze so as to leave one rectangular panel on which there were two dark brushstrokes, a painting on a pot that was reminiscent of Robert Motherwell’s monochromatic gestural forms in which splattering preserved the original sense of viscosity. Both of these works have coarse throwing lines and accentuate Takaezu’s tool of choice. Like her teacher Maija Grotell, she tended to work against firm clay, and the stoneware she favored in the 1950s and 1960s never hid the joinery of her assembled units but retained the facture of deep, rippling grooves from the wheel’s rotational collision with her imprint.

The power of the word form can be traced to two distinct influences on Takaezu: Lenore Tawney’s 1963 exhibition “Woven Forms,” held at the Museum of Contemporary Craft, and the 1947 book The Search for Form by her teacher Eliel Saarinen. Even though his work was never free of classical tendencies, Saarinen’s thesis was that intuition and “personal creative experience,” not historical forms, should be at the core of an education. He begins by describing his successful effort to gain freedom from “the dope” of architectural history and to see for himself, a shift he grounded as both personally and historically necessary for the modern artist to be decisively modern. His argument is by turns learned and intuitive. For instance, his explanation that students should not study the past too much was predicated on the pseudo-scientific and down-to-earth observation that “we cannot live physically on food digested by others.”[28] Grotell and Marianne Strengell, Takaezu’s immediate influences at Cranbrook in the ceramics and weaving departments, instilled a sense of discipline, and the student work left from those years was about a search for pattern and rhythm but within predetermined types of forms: Takaezu made flossa, traditional Scandinavian rugs, and worked within the boundaries of what constituted a vase. Her friend Alice Parrott, a weaver, reminisced that Cranbrook emphasized a “placemat neatness” in student work.[29] Saarinen’s emphasis on intuition must therefore be understood as a celebration of freedom within certain constraints, ones that can be interpreted as tradition but also as decorum.

The aesthetic belief in the value of a placemat, vase, and candlestick was retained at Cranbrook until the 1960s, when a generational shift began to accept off-loom weaving and more raw ceramic gestural constructions as appropriate student outcomes. However, analyzing pottery in terms of form already was part of the Cranbrook education. Saarinen’s book tackled “form migration” from East to West and vice versa. Chinese art is always Chinese art, Saarinen opined, but “sculpture can express ideas in the West that reflect those of the Chinese.”[30] Takaezu’s aptitude for conducting formal analysis and seeing form as separate from cultural context can be noted in her own descriptions of her works from the 1950s that she called “bottles”: “Perhaps these [two-spouted] forms were inspired by pre-Columbian pottery in the Cranbrook Collections. But I certainly did not copy them.” She continued, “I do not make a tea pot and say ‘this is for use.’ Form is my first concern and often the pieces have a later use.”[31]

Describing one’s pottery as a “form” was a self-conscious and slightly pretentious way to name it abstract art. The novel strategic jargon arose in exhibition checklists, including Voulkos’s and those of many others, as the 1960s went on. The gesture caused as many divisions and as much consternation as it gave its users a sense of liberation; the field of studio production, especially in clay, was immediately sundered. Warren Mackenzie famously wrote a tirade in response to Rose Slivka’s “New Ceramic Presence” in Craft Horizons in which he sarcastically lamented, “In the future, we will give up any attempt to make functional ceramics as an expressive form.”[32] To be free of function suggested ontological differentiation, not merely terminological change. The appellation was a way to assert status and new aesthetic ideals in 1963, when Takaezu opted to use it, but was not yet fueled by marketplace ambitions as would occur in later decades.

Even if Takaezu’s cue for this name game came from Lenore Tawney, they should be seen as fellow travelers—while noting that Tawney’s was the more forceful and more audacious personality. After making tapestries both pictorial and abstract, Tawney arrived at the decision to call her individual works “Woven Forms,” as well as to use that for the 1963 exhibition title once she had resolved to make a formal reorientation away from the loom—her weavings literally departed from the weaver’s tool.[33] While Takaezu is credited with making an innovative step in closing her pots into spheres, her turn away from function was not a rejection of the wheel. The wheel remained her primary tool. She might have seen her teacher Claude Horan make such a form, and, if not, she certainly admired firsthand Joseph Hysong’s Narrow-necked Bottle (1961), a closed vessel that was on the cover of the Syracuse national catalog in which she made her debut. The formal decision to close ceramic vessels antedates the rhetorical strategy to name—or not name, as it were—a piece of pottery a Form. The friendship between Lenore Tawney and Toshiko Takaezu has long been recognized in publications because of the numerous photographs of their interactions. For instance, in 1957, at the First Annual National Conference of American Craftsmen in Asilomar, Tawney and Takaezu were photographed together—alongside Heath and Wildenhain (see fig. 11). The snapshot is suggestive of a halcyon moment before Slivka’s essay supposedly separated the fields of art, craft, and design as divergent in status and hierarchy as well as intent.

Whereas Tawney declared that she was an artist and not merely a weaver, Takaezu maintained a stranger position whereby she made art but taught pottery. The wheel was a discipline she maintained, forbidding students to save any work for the first stretch of a semester in order to focus on the process instead of products. Teaching first at the Cleveland Institute of Art and then at Princeton a few days a week, she avoided a full-time position in academia even as she spent an enormous amount of time traveling and conducting workshops. This latter activity is important in terms of situating Takaezu in the fraught relationship between art and craft. The pace of workshops is steady and seemingly averse to the ideal of a focused and slow practice, but Takaezu and many others seemed energized by the process of conducting demonstrations, a peculiar type of event distinct to the milieu of craft. These short-term residencies of one or two weeks, still a defining feature of the field, were captured in photographic essays that showed Takaezu transforming her process into discrete steps, another measure of how the tool of the wheel defined her practice and persona. Whereas Voulkos was an entertaining instructor, a performer with bravura, Takaezu and Karnes were known for their rigor and quiet intensity. Tawney and most others who defined themselves as artists declined to do “demos” as visitors to schools or museums, and the division remains a professional boundary marker to this day.

Although Takaezu’s forms were defined in Objects: USA as “delicate,” “lyrical,” and “intimate,” the catalog also noted a peculiar feature: her pots rattled.[34] Her inclusion of clay within the interiors resulted, intentionally, in clinking sherds. In 1969 both the pots and the rattling were considered a “blending of the East and West.” The problematic exoticization of Takaezu as a foreigner was a constant in her life; museums in the past decade continue to refer to her as a “Japanese potter,” even though she was born in Hawaii. Her older brothers had been enlisted in the U.S. military but when she went to Cranbrook, and ever after, she was interpreted as having a significant aesthetic relationship to Asia. Although ancient indigenous American potters also made rattling pots—sometimes inside tripod legs—Objects: USA interpreted the sounds as Hawaiian waves “breaking upon silent shores.” Takaezu navigated sexism and both anti-Japanese sentiment and the romanticization of Japan—with quiet acceptance. She considered herself as American as Peter Voulkos.

Historically, one mode of testing pottery was the clarity of its ring, to sense if there were cracks and to gauge the density of the clay body. Takaezu undermined such a sense of purity: sound in Takaezu’s pottery is a quietly articulated threat, not spoken by the author to their patrons but implanted in the pot as a performative gesture. The mortal sound is anything but oceanic or becalming. The rattle affords a premonition of breakage. It runs counters to the placid grace and contemplative seduction of the throwing lines and glazes. If Takaezu’s ridged throwing lines are the structure—the warp over which she runs glazes as a weft—then the rattle runs counter to this sense of integration by calling attention to itself as a fragment that defines the interior, a space to which we will never gain access except by breaking into it.

Whereas Voulkos’s cuts into clay literalize modernist rupture, Takaezu’s are made with great subtlety. To compare pottery to photography, Roland Barthes offered readers two terms, studium and punctum, to suggest that such culturally loaded artifacts operate on at least two levels.[35] When we read the pot as a pot, or a photograph as a document of a person or place, studium denotes our cultural, linguistic, and political apprehension of facts. Punctum denotes the personal touch that establishes a direct relationship with the object or person. If Takaezu established an attractive, seductive artifact that suggested it was a completed gesture in its visible throwing marks, she also introduced trauma, so that her pottery is not solely about integration and raising a bowl into a closed sphere on the wheel. If a splash of pink and gray glaze on a Takaezu “form” suggests sky meeting water, then this beauty is given an undertow, or a specific gradient of sand underfoot by the noisy pebble that rolls unseen in our hands but out of our grasp.

This interpretation focuses on Takaezu’s smaller works. Her Star series, however, which she began at age seventy-five, is a dramatic expansion in size—and the crowning achievement of her life’s work (fig. 18). The monumentality of her late works is incredible to reckon; centering twenty to thirty pounds of clay in her seventies and eighties is not a minor achievement. Stacking thrown units, even with the aid of college students, required Takaezu to stand on chairs and ladders above the wheel. The grandeur of these large forms as a field is compelling and immersive. They populate a room not with a human presence but as geological protrusions. Takaezu’s visual illusions of layered glazes are tempting and yet often illusionistic. On her small plates she implied the intersection of two planes and then made us reach out for confirmation only to discover the perceived glaze demarcations were intangible. On her large Star works, the sense of touch becomes all the more imperative yet just as inconclusive. Takaezu’s ceramic monuments appear so triumphant that they might contradict the hypothesis just put forward, that the sound and space of the interior of her forms were an emotional counterpoint. However, these large works can also be assessed as stacked thrown forms that contain within them a cavity the approximate size of the artist’s own body. These ceramic forms, named after constellations (which themselves are mythical forms of illusionary bodies), remain unsettling and ambiguous and decidedly part of classical Western culture. When visitors walk among the Stars, self-concealment and the substitution of clay forms for human bodies become a complex game of abstraction and anthropomorphic suggestion. The surfaces of the stars are tactile and illusionistic—we perceive optical lines and horizons in the glaze, but our fingers do not confirm they are truly present.

Conclusion

There are three obvious reasons to value Heath, Karnes, and Takaezu. The physical objects they made have endured and remain avidly collected despite their modest critical acclaim and despite a lack of interpretation about the work. Second, their work documents the breadth of ways that the potter’s wheel was a disruptive technology in the twentieth century. Wheel-throwing was a process that crossed the categories of art, craft, and design. The wheel shows these to be culturally constructed terms, not incompatible disciplines. Third, they stand as under-recognized women artists who succeeded in spite of a system conspiring against them. In 2016 the Museum of Arts and Design opens a new retrospective, “Voulkos: The Breakthrough Years,” and it will be intriguing to see if the exhibition reflects waves of feminism since Rose Slivka’s 1964 deification. Advance promotion states that in “defying mid-century craft dictums of proper technique and form, Voulkos completely reinvented his medium,” reiterating Slivka’s critical appraisal even more stridently than did Yale’s 2015 exhibition “The Ceramic Presence in Modern Art,” which merely borrowed her essay’s title. While Voulkos might have made interesting art, to indulge in hagiographic celebration ad nauseam reveals a lack of imagination; worse, museums’ capability for criticism is curtailed by Voulkos’s lion’s share of the art market. A Voulkos is still not worth as much as a pot by Pablo Picasso or Lucio Fontana or Jackson Pollock, but it remains a categorical leap beyond the work of any women artists.

M. C. Richards tried to articulate the sense of precarious balance in “centering,” “which will enable us to step along that thread [of life] feeling it not as a thread but as a sphere.”[36] Her goal was not the perfection of an artifact. “What I care about, it is the person,” wrote Richards. “This is the living vessel: person. This is what matters.”[37] Here, we can sense that Richards’s centering and Voulkos’s violation were not necessarily opposites. Perhaps after sipping from a Heath cup, sitting on a Karnes garden stool, or listening to a Takaezu pot rattle, it is we who experience metaphorical human bodies as fragile porcelain dolls. If we move away from canons, marketplace frameworks, and especially away from either a purely verbal or a purely literal reading of violated pottery to a more nuanced and multisensorial appreciation for what the wheel meant in ceramics at mid-century, the abundance of diverse modes of self-realization is breathtaking. The wheel was a way to break tradition and also sustain convention, “both/and,” not “either/or.” Through a real reverence for the complexity of the tool and these artists, we can begin to understand how it was both a habit of working and a way of thinking. It also became a way of unmaking, and undoing skill. Most important, by remembering the oscillation of this larger cast of individuals instead of one sole hero as a focus, we can approach the complexity of these women’s work, where classicism and order intersect with trauma and the subtle threat of chaos. License and decorum might appear as antipodes, but perhaps self-invention requires revolutions in both extremes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I thank Peter Russo and Sequoia Miller for their close reading of this manuscript and their insightful comments. Miller and John Stuart Gordon generously invited me to present a version of this essay at a Yale University Art Gallery symposium. Jenni Sorkin, Ulysses G. Dietz, Edward S. Cooke, Elisabeth Agro, and Sarah Warren were wonderfully responsive listeners; the comments of each improved the text. My research on Karen Karnes has benefited enormously from the generosity of Mark Shapiro, and Jay Stewart richly expanded my awareness of Edith Heath’s legacy. I am grateful for my interviews with Herbert Cohen, Karen Karnes, David Weinrib, and Zeb Schachtel. My inquiry into the wheel began with stimulating discussions with the engaging Freddy Fredrickson in 2007, and my understanding of it has been refined through dialogue with Kevin Millward. For the significance of “quietly subversive” pots I thank Cheryl Buckley’s contribution to the exhibition catalog Women Designers in the USA, 1900–2000 (New York: Bard Graduate Center and Yale University Press, 2000).

Lee Nordness, Objects: USA (New York: Viking Press, 1970), pp. 61, 81; Linda Nochlin, “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?,” Art News 69 (January 1971): 22–39; Cheryl Buckley, Potters and Paintresses: Women Designers in the Pottery Industry, 1870–1955 (London: Women’s Press, 1990); Pat Kirkham, ed., Women Designers in the USA, 1900–2000: Diversity and Difference, exh. cat. (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, in association with Bard Graduate Center for Studies in the Decorative Arts, 2000).

Rose Slivka, Peter Voulkos: A Dialogue with Clay (New York: New York Graphic Society, 1978), p. 12; Andrew J. Perchuk, “Time in Mid-Twentieth Century Ceramics,” American Art 21, no. 1 (Spring 2007): 11.

Peter Dormer, “The Ideal World of Vermeer’s Little Lacemaker,” in Design after Modernism: Beyond the Object, edited by John Thackara (London: Thames and Hudson, 1988), p. 144.

Mary Caroline Richards, Centering in Pottery, Poetry, and the Person (Middletown, Conn.: Wesleyan University Press, 1964), p. 4.

Perchuk, “Time in Mid-Twentieth Century Ceramics,” p. 11.

Oral history interview with Susan Peterson, March 1, 2004, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Elaine Levin, “Millard Sheets and the Impetus for the Ceramic Revolution of the 1950s,” in Christy Johnson, Common Ground: Ceramics in Southern California, 1945–1975 (Pomona, Calif.: American Museum of Ceramic Art, 2012), p. 14.

Oral history interview with Susan Peterson.

Billie P. Sessions, “Ceramics in Academia: A Site of Unique Circumstances,” in Common Ground, p. 72 n. 28.

Cheryl Buckley, “Subject of History? Anna Wetherill Olmsted and the Ceramic National Exhibitions in 1930s USA,” Art History 28, no. 4 (September 2005): 517.

Laura Andreson, interview with Elaine Levin, June 1974, in Levin, “Millard Sheets and the Impetus for the Ceramic Revolution of the 1950s,” p. 17.

Oral history interview with Susan Peterson.

Patent no. US 2174061 A, available online at https://www.google.com/patents/US2174061?dq=variable+speed+potter%27s+wheel&hl=en&sa=X&ei=1VllVLWtF4HCASq3YC4Cg&ved=0CCYQ6AEwAQ (accessed November 11, 2014).

Ezra Shales, Made in Newark: Cultivating Industrial Arts and Civic Identity in the Progressive Era (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rivergate Books, an imprint of Rutgers University Press, 2010), p. 259.

Twelfth National Ceramic Exhibition (Syracuse, N.Y.: Syracuse Museum of Fine Arts; Onondaga Pottery Company, 1947), p. 11.

Oral history interview with Susan Peterson.

V. Gordon Childe, “Rotary Motion,” in A History of Technology, vol. 1, From Early Times to Fall of Ancient Empires, edited by Charles Singer, E. J. Holmyard, and A. R. Hall (Oxford, Eng.: Clarendon Press, 1954), p. 204.

George M. Foster, “The Potter’s Wheel: An Analysis of Idea and Artifact in Invention,” Southwestern Journal of Anthropology 15, no. 2 (Summer 1959): 100. “Perhaps the most common argument against the evolutionary sequence hypothesis is that, since women do not use the wheel, they could not have invented it. How could a turntable customarily used by women, argues van Gennep, develop into a wheel used by men? This type of argument is based on the early assumption, now known to be only partially true in primitive societies, that hand-made pottery is alone the work of women. In many places, we now know, men using hand techniques are equally important in pottery manufacture” (p. 116).

Dr. Billie Sessions credits Carlton Ball with introducing the “Netherby wheel” in 1944 at the Mills College Ceramic Guild, although this seems rather improbable, considering its name, so the history and contributions of Elena Netherby remain worthy of future research. See Sessions, “Ceramics in Academia,” p. 72 n. 28.

Mark Shapiro, ed., A Chosen Path: The Ceramic Art of Karen Karnes, exh. cat. (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010).

Amos Klausner, Heath Ceramics: The Complexity of Simplicity (San Francisco, Calif.: Chronicle Books, 2006).

Sheila Hibben, “On and Off the Avenue: About the House,” New Yorker (September 17, 1949): 86.

Classifieds, New Yorker (December 17, 1949): 92.

Rob Forbes, in Klausner, Heath Ceramics, p. 25.

Herbert Cohen, in conversation with the author, May 29, 2014. To benchmark Karnes’s skill in retrospect is difficult. It is important to note that when she returned from Italy, she shipped her wheel back across the Atlantic, having formed an emotional (or financial) attachment to it.

Dido Smith, “Karen Karnes,” Craft Horizons 15, no. 5 (May–June 1958): 10–14; Jody Clowes, “The Woman behind the Pot,” in Shapiro, ed., A Chosen Path, 27–45.

Voulkos profoundly admired both Takaezu and Karnes, followed their work, and was on a first-name basis with both. While he famously played the rascal for the camera and crowds, these women did not—such behavior by women would not have been socially sanctioned—yet they laughed at his coarse and colorful language.

Undated clipping, Los Angeles Times, Toshiko Takaezu Foundation Archive.

Eliel Saarinen, The Search for Form in Art and Architecture (New York: Reinhold, 1948), p. xvi.

Alice Parrott, “...The Right, Unhurried Place,” Craft Horizons 20, no. 1 (January–

February 1960): 20.

Saarinen, Search for Form, p. 176.

Undated clipping, Los Angeles Times, Toshiko Takaezu Foundation Archive.

Warren Mackenzie, “Letter to the Editor,” Craft Horizons 5 (November/December 1961): 45.

Elissa Auther, String, Felt, Thread: The Hierarchy of Art and Craft in American Art (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010).

Nordness, Objects: USA, p. 81.

Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography, translated by Richard Howard (New York: Hill and Wang, 1981).

Richards, Centering, p. 6.

Ibid., pp. 34–35.