Teabowl and saucer, Jingdezhen, China, 1760–1775, decoration added in the United States ca. 1925. Porcelain. D. of saucer 5 1/2". (Reeves Collection, Washington & Lee University, Gift of Richard and Catharine Hubbard; photo, Robert Hunter.)

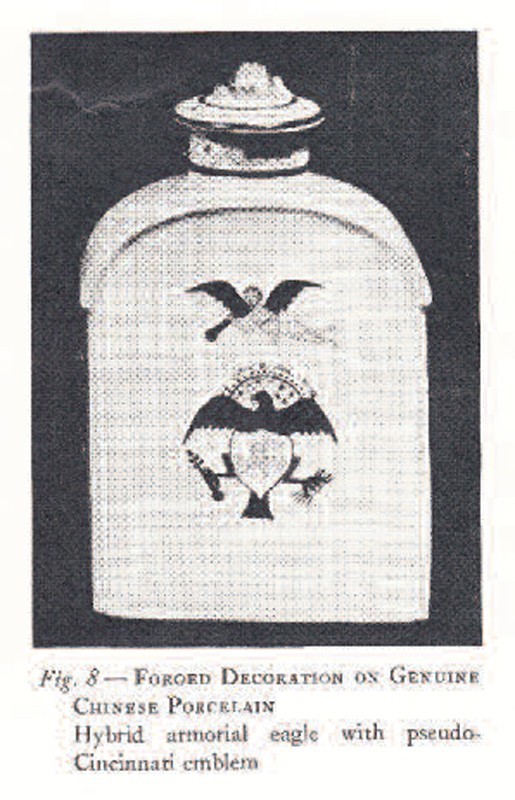

Tea caddy, Jingdezhen, China, 1760–1775, decoration added in the United States ca. 1925. Porcelain. H. 5 1/2". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum, Bequest of Henry Francis du Pont, 1963.716a,b.)

Illustration from Homer Eaton Keyes, “Imitations of Chinese Lowestoft,” Antiques 24, no. 4 (October 1933): 143.

Salad bowl, Jingdezhen, China, 1784, decorated in Guangzhou (Canton), China. Porcelain. W. 9 1/4". (Reeves Collection, Washington & Lee University, Gift of the Edward H. Thompson Family.)

Teabowl, Jingdezhen, China, 1800–1820, decoration added in the United States ca. 1925. Porcelain. H. 1 7/8". (Reeves Collection, Washington & Lee University, Gift of Euchlin and Louise Herreshoff Reeves; photo, Robert Hunter.)

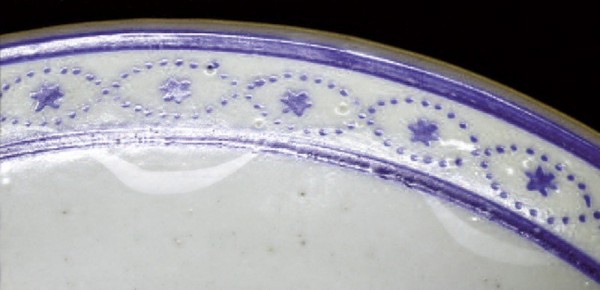

Detail of the saucer illustrated in fig. 1, photographed in raking light.

Detail of the teabowl illustrated in fig. 1, photographed in raking light.

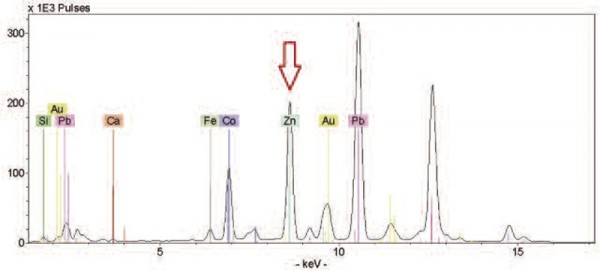

p-XRF analysis of the blue enamel on the eagle on the saucer illustrated in fig. 1. Note the peak representing zinc (Zn) shown at the arrow.

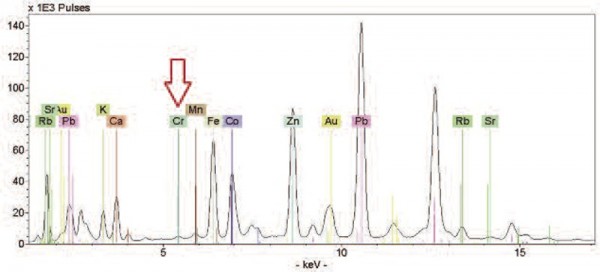

p-XRF analysis of the sepia enamel on the figure of Fame on the teabowl illustrated in fig. 1. Note the small but significant peak presenting chromium (Cr) shown at the arrow.

In 1933 Homer Eaton Keyes, the first editor of Antiques magazine and an expert on Chinese export porcelain, warned that “the most dangerous imitations of Chinese Lowestoft are those achieved by removing the decoration from genuine old pieces or Oriental ware and substituting a rarer design that materially enhances their apparent value.”[1] What Keyes was referring to, was a growing number of pieces of fake Chinese export porcelain decorated with American emblems that were emerging on the antiques market in the 1920s and early 1930s. Among these was what Keyes described as “weird versions of the Cincinnati pattern”—pieces decorated with a figure of Fame holding an eagle with a shield on its breast emblazoned with initials (fig. 1).[2]

Approximately twenty pieces of these “weird versions” are known, all of which are tea and coffee wares.[3] They are found with both overglaze blue and gold and sepia-and-gold enamel decoration, and with four different border patterns: a gold band; a blue-and-gold intertwined chain and star; a blue intertwined chain and star; and no border at all.[4] Four different sets of initials—W, NEA, WSA, and DL—personalize the shields on several pieces, and a simple floral spray decorates the shield of one other, suggesting that there were at least five different services.[5] A possible indication that all is not what it seems with this group is the fact that, in some instances, the same initials are found on pieces with different borders.[6]

The pieces appeared on the market in the mid-1920s. Henry Francis du Pont, one of the leading collectors of Chinese export porcelain of the period, bought a “Lowestoft Tea Caddy and Cover, Order of the Cincinnati” from New York antiques dealers Ginsburg & Levy on December 11, 1925, for $350, and another “Cincinnati Lowestoft Tea Caddy, blue trellis dec. on top” on December 2, 1927, from dealer J. Grossman for $850 (fig. 2).[7] Similarly decorated pieces were acquired by other leading collectors, such as Helena Woolworth McCann and Euchlin and Louise Reeves.[8]

At first glance, these pieces seem to date to the late eighteenth or early nineteenth century, and relate to George Washington’s export porcelain decorated with the Society of the Cincinnati insignia. The high price paid by du Pont and other knowledgeable collectors suggests that these works were considered genuine, and published as such by the 1950s.[9] But stylistic differences, physical evidence, and scientific evidence all bear out Keyes’s warning that some, of the pieces in this group are, in his words, “FORGED DECORATION ON GENUINE CHINESE PORCELAIN / Hybrid armorial eagle with pseudo-Cincinnati emblem” (fig. 3).[10]

Stylistic Evidence

The allegorical figure of Fame originates from the ancient Greek goddess Pheme (Fama, in the Roman pantheon), who personified positive renown and negative rumor and who was the messenger of Zeus. According to George Richardson’s Iconology; or, a Collection of Emblematical Figures, published in 1779, Fame was “represented by the figure of a woman with large white wings at her shoulders, holding a trumpet. . . . [T]he wings denote the candour and velocity of Fame; the trumpet signifies that the voice of Fame resounds, like this instrument, and encourages men to imitate the virtuous.”[11] This depiction was standard for Fame from at least the sixteenth century, when she became popular as a decorative motif on a range of objects, including ceramics.[12]

The eagle is an adaptation of the Great Seal of the United States, which was adopted by Congress in 1782 as the country’s official emblem. The seal consists of a shield with thirteen red and white stripes, representing the original thirteen states, under a blue chief, representing Congress, borne on the breast of an American eagle.[13] Designed for use on official documents, the Great Seal also became a popular motif on objects ranging from furniture to textiles to ceramics. It proved a popular decorative motif for Chinese export porcelain, and on many pieces it was common for the stripes and chief of the shield to be replaced with the initials of the original owner.[14]

The figure of Fame and the eagle that decorate the pieces under study are similar to those found on what is arguably the most famous Chinese export porcelain made for the American market: George Washington’s Cincinnati service. Commissioned in 1784 by Samuel Shaw, the first American merchant to go to China, the original service consisted of 302 pieces, each of which was decorated with an underglaze blue border and a figure of Fame holding the badge of the Society of the Cincinnati: an eagle with a shield on its breast containing a vignette of Cincinnatus, the ancient Roman hero after whom the society is named (fig. 4).[15]

The Society of Cincinnati, an organization of Revolutionary War officers founded in 1783, was named after Lucius Quinctius Cincinnatus, a Roman farmer turned military leader who rescued Rome and then relinquished his power to return to his farm. Cincinnatus was seen by many as the model of a selfless patriot, and George Washington, a farmer who had led American troops to victory, served two terms as president, and then retired to return to Mount Vernon, was seen by many as a modern-day Cincinnatus.

Washington, the first president of the society, bought the service in 1786 and used it at Mount Vernon and the president’s mansions in New York and Philadelphia. Conscious that his actions were carefully watched and that he was creating the model for the office of the U.S. presidency, Washington may have used the Cincinnati service to reinforce his identity as a modest, selfless leader in a new, democratic society who would serve his country without expectation of reward and then relinquish power back to the people.[16]

Washington’s Cincinnati service is one of the most prized examples of American-market export porcelain, and it has been avidly studied, published, and collected since the mid-nineteenth century.[17] Any piece from the service was considered one of the crowning glories of any great Chinese export collection, and was priced accordingly; Henry Francis du Pont paid $71,550 for sixty-nine pieces from the service in 1927 and 1928.[18]

The juxtaposition of Fame and the eagle on the pieces in the group under study was almost certainly meant to suggest some connection with the Society of Cincinnati, and several of the pieces have the initial W on the shield, further suggesting a connection to George Washington (fig. 5).[19]

Despite the similarity of the decoration to pieces of American-market export porcelain known to be genuine, elements of the design on the pieces in this study raise questions about their authenticity. The most questionable element is the nude figure of Fame. While Fame was occasionally depicted in the nude in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, she more commonly was shown at least partially clothed. Rees’s Cyclopedia recorded in 1810 that “the common representation of Fame exhibits her in a flying attitude, sounding a trumpet . . . with a flowing robe.”[20]

Depictions of a naked Fame would have been especially unusual in the United States, where depictions of nudity in art were often frowned on. While the growing popularity of neoclassical design made figures of nude or partially draped women more common in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, they were generally not seen as suitable for American audiences. Regarding a collection of casts of Greek and Roman statues, in 1802 the United States minister to France Robert R. Livingston wrote, “though these statues are viewed by the most delicate women here without a blush, yet the modesty of our country women renders a covering necessary.”[21]

Artists, craftsmen, and merchants were aware of the difficulty of marketing paintings or objects with nude figures to American consumers. In 1809 artist John Vanderlyn warned one of his clients that he might not want Vanderlyn’s painting of a nude because, “I am not sure the subject will please so as to be desirous of possessing it for it is perhaps not chaste enough for American eyes, at least to be displayed in the dwelling of any private individual to either the company of a parlor or drawing room.” When James Monroe ordered new furniture for the White House from France, his agent Joseph Russell wrote saying they had “great difficulty in getting Pendules [clocks] without Nudities, and were . . . forced to take the two models we have bought on that account.”[22]

Thus, it seems unlikely that an eighteenth- or early-nineteenth-century American consumer or merchant would have commissioned porcelain decorated with such a blatant depiction of nudity. And while one piece or set could be seen as an anomaly, to have twenty pieces, representing up to five sets, is less plausible.

Some of the borders that appear on pieces in the group are also curious. The most common border consists of two intertwined, meandering lines enclosing stars—sometimes executed in all blue enamel, sometimes in blue enamel with gold stars (see fig. 1). While stylistically the border conforms to the neoclassical style popular in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, a search of collections and the literature has found no similar border on genuine pieces.[23]

Physical Evidence

The execution of the decoration also raises questions: the application of the blue enamel seems less carefully painted than what is typically found on genuine Chinese export, and the enamel is thick in some places and thin in others. As Keyes described,

Seldom, however, can the modern imitator give a wholly convincing air to his handiwork. Something will be wrong about his touch, or in the forms he outlines. The swift, sure, calligraphic stroke of the Chinese artist will be wanting, and his amusing distortions of human and animal figures will be bunglingly translated. Such disqualifications will usually be felt, even if not fully recognized by the sensitive eye; but the subtlest admonition to consultation and comparison thus conveyed should never be ignored.[24]

Even more damning is the fact that several pieces in the group bear evidence of earlier decoration that has been removed. When viewed in raking light, ghosts of scratched-off borders, medallions, and coats of arms are visible. For instance, ghosts of a swag-and-bamboo border appear underneath the intertwined chain and star border on the saucer illustrated in figure 1 (fig. 6).[25] Swag-and-bamboo borders date roughly between 1765 and 1775, suggesting the correct date for the porcelain and their original decoration.[26]

The teabowl illustrated in figure 1 shows residual evidence beneath the eagle of a floral spray, a popular motif in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century.[27] Here, too, is clear evidence of scratching, suggesting that the original decoration was abraded off (fig. 7).

Another teabowl in the Reeves Collection (1967.1.565) shows faint traces of a circular medallion containing an initial, a style that was popular in the first decades of the nineteenth century. Similarly, a cream jug in the same collection (1967.1.379) shows faint traces of an urn-shaped shield with mantling, which most likely was a coat of arms or a shield bearing initials, a motif popular from the 1770s into the early nineteenth century.

It is possible that some of the original decoration, like the circular medallion with initials, was painted in gold. Gilded decoration, which was fired at a low temperature and therefore fixed poorly to the surface, was especially susceptible to wear and so would have been easy to remove with acid or even just physical abrasion. Overglaze enamels would have been more difficult to remove than gilded decoration, but were still relatively easy to remove, probably with acid and abrasion, as is seen in the scratch marks on the teabowl illustrated in figures 1 and 7.

Chemical Evidence

The most convincing evidence that the objects under discussion are not genuine is the fact that the enamels used on a number of them do not match eighteenth- and early-nineteenth-century Chinese enamel technology. The enamels were analyzed using X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy, a nondestructive technique in which an incident X-ray beam is used to excite atoms in the overglaze enamels, glaze, and body. The X-rays emitted from all of these components can provide information about the colorants and fluxes used.[28]

Zinc, probably used as a fluxing agent, was found in high concentrations in the blue enamel on several of the pieces in the study.[29] The presence of zinc is strongly suggestive of twentieth-century manufacture. It is present in the enamels on a group of Chinese export porcelain, decorated with a scene of the signing of the Declaration of Independence, that is thought to have been made in China in the 1920s or 1930s, and is also present in the enamels on fake pieces of George Washington’s Cincinnati service that were created in Europe or America in the 1970s by adding the figure of Fame and the Cincinnati eagle to genuine late-eighteenth-century Chinese export plates (fig. 8).[30]

A tin oxide opacifier also was inferred in the blue enamel on several pieces, rather than the typical lead arsenate opacifier typically found on genuine Chinese enamels of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.[31]

Another anomalous element is bismuth, which is found on several pieces in the gilding decorating Fame and the eagles. Bismuth was used as a flux to bind the gold to the glaze but has not been identified in gilded decoration on genuine late-eighteenth-century Chinese export porcelain, suggesting that it is a marker for later gilded decoration.[32] In fact, bismuth is found on the eagle and figure of Fame on one of the teabowls but is not found on the gilded rims and small floral sprays, suggesting that the latter probably date from the cups’ original decorative scheme and that Fame and the eagle do not.[33]

The final, and perhaps most damning, anomalous element present on some of the pieces in this group is chromium, which is found in the sepia enamels used to paint the figure of Fame on several pieces.[34] Chromium was discovered in 1797 and is first known to have been used on ceramics in 1802 at Sèvres.[35] Its use in China is not known before the twentieth century, making it highly unlikely that the decoration could be period (fig. 9).[36]

Although the chemical composition of the enamels on related wares virtually guarantees them to be later, several pieces from the group were found to have period-appropriate enamel compositions, consistent with late-eighteenth- and early-nineteenth-century Chinese export porcelain.[37] While this raises the possibility that these pieces could be genuine, their stylistic similarity to the others—with the incongruous nude figure of Fame, the similar style of painting, and the presence of initials that match those found on presumed fakes—suggests that these, like the others, bear later decoration on earlier porcelain.[38] Just because a new chemical composition was introduced does not mean that old ones did not continue to be used, so if the forger (or forgers) made the pieces over a period of time, they could likely have obtained different batches of enamels with different compositions.

Discussion and Conclusions

The combination of stylistic, physical, and chemical evidence shows that at least some, and most likely all, of the pieces decorated with the naked figure of Fame and an eagle are not late-eighteenth- or early-nineteenth-century originals but, rather, fakes made in the early twentieth century.

But why would such fakes have been made, and why in the first decades of the twentieth century? Studying these fakes not only helps us distinguish the genuine from the spurious, it also provides a picture of the collecting and decorating tastes of the 1920s and 1930s, the development of the field of ceramics study, and the growing skill and knowledge of ceramic scholars, collectors, dealers, and fakers.

Chinese export porcelain decorated with American symbols began being produced soon after merchants from the United States first began trading with China in 1784, and it continued to be made into the 1820s. While the pieces of specially commissioned porcelain with American symbols are relatively small in number, they have long been popular among collectors, as they combined patriotism, the perceived romance of the China trade, and the historic notion that Chinese porcelain was the finest ceramic ever made.

To early collectors, Chinese export porcelain was not just a foreign product but also rather intrinsically American. As R. T. Halsey, one of the founders of the American Wing at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, wrote: “Possibly no element which went into the making of the American home is more characteristic than the Chinese table-ware which formed part of the home cargoes of our early ships in the Oriental trade.”[39] Pieces decorated with eagles and pieces that were similar to George Washington’s Cincinnati service would be sure to find appeal among patriotic collectors.

As interest in Chinese export porcelain made for the American market grew in the first decades of the twentieth century, demand increased, supply remained static, and prices rose accordingly. Not surprisingly, in the 1920s manufacturers in Europe and China began making reproductions of historic pieces, and some unscrupulous artisans and dealers began to produce and sell fakes to take advantage of this growing market.

There were several instances of such fakes emerging on the market in the 1920s. In Keyes’s article in Antiques he documented not just the “weird versions of the Cincinnati pattern” that are the subject of this study but also the tomb of George Washington (a plate “from which the original enamel flower sprigs had been removed to make way for a spread eagle perched on accouterments of war”) and the arms of the State of New York.[40]

Keyes warned that while some of the modern fakes made in Europe and China were relatively easy to identify, it was far harder to identify forgeries “achieved by removing the decoration from genuine old pieces or Oriental ware and substituting a rarer design. This, obviously, is done with dishonest intent; and because the porcelain itself is beyond criticism, the forgery is often hard to detect and almost impossible to prove.”[41]

Among these fakes was a group decorated with the arms of the State of New York, that was the subject of a court case and articles published in 1930 in Time magazine and the New York Times.[42] As the Time article explained: “Genuine plain old Lowestoft is used as a basis for the fake ware. To give the china greatly increased value to collectors, artists are employed to decorate the plain ware with early American motifs, such as Salem ships. The modern decorations, which are fired on the china, are said to be readily recognizable by experts.”[43]

The collector and dealer Edward Crowninshield was responsible for discovering the forgery, according to Time: “A more careful examination convinced him that the service was of plain Lowestoft porcelain which had been skillfully decorated on top of the glaze, then sandpapered to give approximately the correct ‘feel.’”[44]

The Time article went on to describe how officials “added immeasurably to the detective-story air of the whole business by producing the traditional sinister oriental, an expert Japanese repairer of antique porcelain who labors in a little art shop on Sixth Avenue, Manhattan and is known as ‘Mr. Chicago.’ Inspector Liese insisted last week that Mr. Chicago of Japan is the real perpetrator of the forged Lowestoft, but since china-painting is not yet a criminal offense, Mr. Chicago remains outside the law.”[45]

The removal of old enamel and gilding, the preparation and application of new enamel decoration, and the firing of new enameling in a muffle kiln would have been relatively easy, and in fact was hardly a new phenomenon. The ceramics scholar Joseph Marryat wrote in 1850 that

the old stocks in the Royal Manufactory at Sèvres, were put up to auction, and bought by certain individuals, who also collected all the soft ware they could find in the possession of other persons. The object of this proceeding for a long time remained a mystery, but at length the secret transpired, that the parties had discovered a process, which consisted in rubbing off the original pattern and glaze, and then colouring the ground with turquoise or any other colour, and adding paintings or medallions in imitation of the style of the old “pête tendre;” thus enhancing a hundred fold the value of the pieces.[46]

Adding new decoration to old porcelain would have been even easier in the 1920s, as the proliferation of amateur china painters in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and of ceramics restorers, such as the nefarious “Mr. Chicago,” meant that the tools, overglaze enamels, and talent needed to add decoration to old porcelain were readily available. That is almost certainly what some unethical but talented person did: took mismatched pieces of old porcelain, removed the original and probably worn enamel and gilded decoration with acid and abrasion, and then, using George Washington’s Cincinnati porcelain as inspiration, decorated the now-blank porcelain with a new border and central decoration of Fame and an eagle. The result was something that had an air of authenticity about it and was certain to appeal to collectors looking for pieces that evoked America’s glorious past.

Though the Chinese export objects decorated with a nude figure of Fame and an eagle did not gain the same level of notoriety as the pieces decorated with the arms of New York, they were recognized as fake by Homer Eaton Keyes, who included them in his 1933 article “Imitations of Chinese Lowestoft.”[47] However, that news seems to have been forgotten by the 1950s, when the pieces began to be published as genuine. In 1956 John Goldsmith Phillips illustrated a coffeepot from the Helena Woolworth McCann Collection, describing it as “American market 1795–1800.”[48] But close study of the design, physical evidence, and chemical composition of the group has revealed that they are, in fact, just what Homer Eaton Keyes warned about back in 1933: “most dangerous imitations.”

Homer Eaton Keyes, “Imitations of Chinese Lowestoft,” Antiques 24, no. 4 (October 1933): 143. Keyes used the term Chinese Lowestoft to refer to what is now known as Chinese export porcelain. The term arose in the nineteenth century, when early ceramics scholars mistakenly thought that Chinese porcelain was actually English porcelain made in the city of Lowestoft. Though the error was soon recognized, the terms Oriental Lowestoft and Chinese Lowestoft remained in use into the 1950s.

Ibid.

Examined as part of this study were a teabowl and saucer, another teabowl, and a helmet-shaped cream jug in the Reeves Collection, Washington & Lee University; three teabowls, a teapot, stand, oval dish, and two tea canisters in the Winterthur Museum; two teabowls and matching saucers in a private collection; and a teabowl and saucer in the Cluthe Collection. Known only through publications are a tea caddy, illustrated in ibid., and a coffee pot, illustrated in John Goldsmith Phillips, China-Trade Porcelain (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1956), pl. 100.

One piece, a cream jug in the Reeves Collection (67.379), has no border. Four teabowls—one in the Reeves (67.1.565) and three in the Winterthur Museum (59.86.58–60)—have a gold band at the rim. Five pieces—a teabowl and saucer in the Cluthe Collection and a tea caddy, teapot, and stand at Winterthur (63.716a,b and 73.240a–c)—have a blue-and-gold intertwined chain and star border. Nine pieces—a teabowl and saucer in the Reeves Collection (16.1.1a,b), two teabowls and saucers in a private collection, and a tea caddy, oval dish, and circular dish at Winterthur (63.718a,b, 59.85.61, and 54.64)—have a blue intertwined chain and star border. The tea caddy illustrated in Antiques and the coffee pot illustrated in Phillips’s China-Trade Porcelain have intertwined chain and star borders, but because the illustrations are black-and-white it is not clear whether they are blue or blue-and-gold.

The initial W is found on four teabowls—one in the Reeves Collection (67.1.565) and three in the Winterthur Museum (59.86.58–60). The initials NEA are found on eleven pieces—a teabowl and saucer and a cream jug at the Reeves (16.1.1a,b and 67.1.329); a circular plate, oval dish, and tea caddy at Winterthur (54.64, 59.85.61, and 73.718); three teabowls and saucers in the private collection; and the coffee pot illustrated in Phillips’s China-Trade Porcelain. The initials WSA are found on a teapot and stand at Winterthur (73.240a–c). The initials DL are found on a tea caddy at Winterthur (63.716). The initials on the tea caddy illustrated in Antiques are illegible in the illustration. A saucer in the Cluthe Collection has a floral spray.

“NEA” appears on pieces that do not have a border: a cream jug at Reeves (67.1.329); on pieces with a blue intertwined chain and star border (a circular plate, oval dish, and tea caddy) at Winterthur (54.64, 59.85.61, and 73.718); and two teabowls and saucers in a private collection.

Henry Francis du Pont Day Books, Winterthur Registrar’s Office, Winterthur Museum, Wilmington, Del.

Phillips, China-Trade Porcelain, pl. 100; Thomas Litzenburg, Chinese Export Porcelain in the Reeves Center Collection (London: Third Millennium Publishing, 2003), p. 143.

Phillips, China-Trade Porcelain, pl. 100.

Keyes, “Imitations of Chinese Lowestoft,” p. 143.

George Richardson, Iconology; or, a Collection of Emblematical Figures . . . , 2 vols. (London: Printed by G. Scott, 1779), 2:16, pl. LVII.

Fame appears on pl. 122 of The Ladies Amusement, a collection of designs published circa 1760 that would be “extremely useful to the Porcelaine, and other Manufacturers.” Robert Sayer, The Ladies Amusement (Newport, Eng.: Ceramic Book Co., 1966), p. 122 and title page. Figures of Fame are known on transfer-printed porcelain made by Worcester and Longton Hall. Simon Spero, 18th Century English Transfer-Printed Porcelain and Enamels (Carmel, Calif.: Mulberry Press, 1991), p. 33.

U.S. Department of State, Bureau of Public Affairs, “The Great Seal of the United States,” www.state.gov/documents/organization/27807.pdf (accessed November 15, 2015).

Jean McClure Mudge, Chinese Export Porcelain for the American Trade, 1785–1835 (Newark: University of Delaware Press, 1981), pp. 167–69.

In addition to the service that was sold to George Washington, Shaw commissioned a service for himself and nine tea sets decorated with the society’s eagle (but not the figure of Fame). Susan Detweiler, George Washington’s Chinaware (New York: Henry N. Abrams, 1982), pp. 81–97; Amanda Lange, Chinese Export Art at Historic Deerfield (Deerfield, Mass.: Historic Deerfield, 2005), pp. 250–53.

Detweiler, George Washington’s Chinaware, pp. 81–97.

Benjamin Lossing, Mount Vernon and Its Associations (New York: C.A. Alvord, 1859), pp. 239–40; Alice Morse Earle, China Collecting in America (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1892), pp. 229–48.

Thomas McCreedy Dealer File and Day Books, Winterthur Registrar’s Office, Winterthur Museum, Wilmington, Del.

Teabowl from the Reeves Collection (1967.1.564); teabowls from the Winterthur Museum (1959.85.58–60).

Abraham Rees, ed., The Cyclopaedia; or, Universal Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, and Literature, 41 vols. (1810–24), 14:125.

Robert R. Livingston to Robert G. Livingston, December 23, 1803, quoted in E. McSherry Fowble, “Without a Blush: The Movement toward Acceptance of the Nude as an Art Form in America, 1800–1825,” Winterthur Portfolio 9 (1974): 104.

John Vanderlyn to John Murray, June 12, 1809, quoted in Fowble, “Without a Blush,” pp. 103–21, 111; Joseph Russell to James Monroe, May 25, 1818, quoted in Betty C. Monkman, The White House: Its Historic Furnishings and the First Families (New York: Abbeville Press, 2000), p. 62.

David Howard, Chinese Armorial Porcelain (London: Faber and Faber, 1974), pp. 645–69, 741–76, 971–92; David Howard, Chinese Armorial Porcelain, Volume II (Chippenham: Heirloom and Howard, 2003), pp. 473–509, 600–643; Jean Gordon Lee, Philadelphians and the China Trade (Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1984), pp. 54–57.

Keyes, “Imitations of Chinese Lowestoft,” p. 143.

Saucer in the Reeves Collection (16.1.1b).

Howard, Chinese Armorial Porcelain, p. 386; Howard, Chinese Armorial Porcelain, Volume II, p. 261.

Teabowl in the Reeves Collection (16.1.1a).

Ronald W. Fuchs and Jennifer L. Mass, “Deciphering The Declaration of Independence on Chinese Export Porcelain,” in American Ceramic Circle Journal 15 (2008): 168–87.

Zinc was found in the blue-and-gold enamels on three teabowls with the initials NEA (Reeves Collection 16.1.1a and two in the private collection); three saucers with the initials NEA (Reeves Collection 16.1.1a and two in the private collection); a cream jug with the initials NEA (67.1.379); a circular dish with the initials NEA (Winterthur Museum 54.64); an oval dish with the initials NEA (Winterthur Museum 59.8561); and four teabowls with the initial W (Reeves Collection 1967.1.565, Winterthur Museum 59.85.58–60).

Fuchs and Mass, “Deciphering The Declaration of Independence on Chinese Export Porcelain,” pp. 168–87, 177–78; E. Uffelman, R.W. Fuchs II, P. A. Hobbs, L. F. Sturdy, D. S. Bowman, and D.A.G. Barisas, “Technical Examination of Cultural Heritage Objects Associated with George Washington,” in Collaborative Endeavors in the Chemical Analysis of Art and Cultural Heritage Materials, edited by P. L. Lang and R. A. Armitage (Washington, D.C.: American Chemical Society, 2012), pp. 251–83, 257.

Tin oxide was identified in the blue enamels on three teabowls with the initial W (Winterthur Museum 59.85.58–60); a circular dish with the initials NEA (Winterthur Museum 54.64); and an oval dish with the initials NEA (Winterthur Museum 59.85.61). Pam Vandiver, “The Eighteenth-Century Change in Technology and Style from the Famille-verte Palette to the Famille-rose Palette,” in Technology and Style: Proceedings of a Symposium on Ceramic History and Archaeology, edited by W. D. Kingerly (Columbus, Ohio: American Ceramic Society, 1986), pp. 363–81, 377.

Aniko Bezur and Francesca Casadio, “The Analysis of Porcelain Using Handheld and Portable X-ray Fluorescence Spectrometers,” in Handheld XRF for Art and Archaeology, edited by Aaron Shugar and Jennifer Mass (Leuven: Leuven University Press, 2012), pp. 249–311, 272.

Bismuth was found in the gold of the eagle but not the rims on three teabowls with the initial W (Winterthur Museum 59.85.58–60).

Chromium was identified in the sepia enamels on three teabowls with the initial W (Winterthur Museum 59.85.58–60) and a circular dish with the initials NEA (Winterthur Museum 54.64).

Tamara Préaud, The Sèvres Porcelain Manufactory: Alexandre Brongniart and the Triumph of Art and Industry, 1800–1847 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1997), p. 58.

Fuchs and Mass, “Deciphering The Declaration of Independence on Chinese Export Porcelain,” pp. 177–78.

Pieces studied that had an enamel composition consistent with eighteenth- and nineteenth-century famille-rose enamels include two tea caddies (Winterthur 63.716 and 63.718); a teapot and stand (Winterthur 73.24a–c); and a teabowl and saucer in the Cluthe Collection.

Ten pieces studied are decorated with the initials NEA. One piece, a tea caddy, was decorated using an enamel technology consistent with eighteenth- and early-nineteenth-century Chinese export porcelain; the remaining pieces—three teabowls and saucers in the Reeves Collection (16.1.1) and two in the private collection; a cream jug at Reeves (67.1.379); a circular dish in the Winterthur Museum (54.64); and an oval dish in the Winterthur Museum (59.8561)—all showed anomalies in their enamel composition that suggests they are later-decorated.

R.T.H. Halsey and Elizabeth Tower, The Homes of Our Ancestors (New York: Doubleday, Doran and Co., 1925), p. 201.

Keyes, “Imitations of Chinese Lowestoft.”

Ibid.

Ibid.; “Faked Lowestoft,” Time 16, no. 18 (November 3, 1930): 65; “Woman Is Jailed in Chinaware Deal,” New York Times, October 22, 1930, p. 18.

“Woman Is Jailed in Chinaware Deal.”

“Faked Lowestoft,” p. 143.

Ibid.

Joseph Marryat, Collections Towards a History of Pottery and Porcelain, in the 15th, 16th, 17th, and 18th Centuries: With a Description of the Manufacture, a Glossary, and a List of Monograms (London: J. Murray, 1850), pp. 200–201.

Keyes, “Imitations of Chinese Lowestoft.”

Phillps, China-Trade Porcelain, p. 202.