Artist unknown, England or America, ca. 1820-1830. Watercolor and gouache on paper. 9" x 6 3/4". (Private collection.) A rare period image of a china mender operating a bow drill to prepare a cracked bowl for a staple repair.

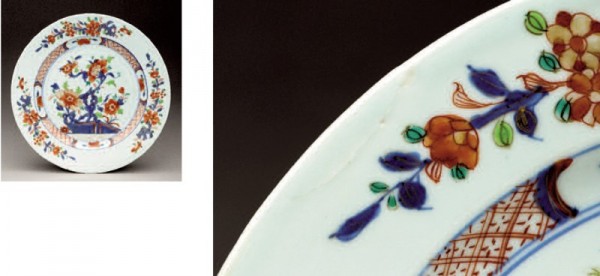

Plate, Jingdezhen, China, ca. 1735. Hard-paste porcelain. D. 9". (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Museum Purchase, 1968-6.) Note detail of rim showing repair before firing.

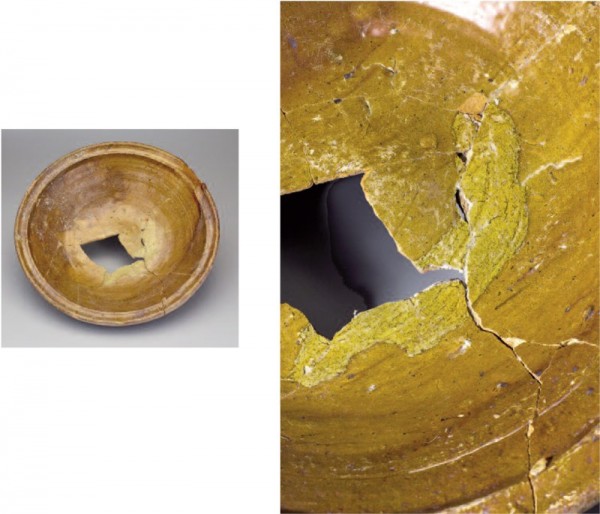

Milk pan, England, ca. 1730. Slip-decorated, lead-glazed earthenware. D. 14 1/2". (Courtesy, Kingsmill Resort, Williamsburg, Virginia; photo, Robert Hunter.) Excavated in Kingsmill, Virginia.

Dinner just over, or The Consequences of a Toe tripping at the Top of a Stair-Case, engraved and published by J. Baldrey, Cambridge, England, July 20, 1799. Black-and-white etching with period hand color. (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Museum Purchase, 1957-30.)

Nicolas Lancret, Luncheon Party in a Park (detail), France, ca. 1735. Oil on canvas. 21 5/16" x 18 1/8". (Courtesy © 2017 Museum of Fine Arts Boston, Bequest of Forsyth Wickes, The Forsyth Wickes Collection, 65.2649.)

A Macaroni Dressing Room (detail), published by Matthew Darly, London, England, 1772. Black-and-white etching and line engraving with period hand color. (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Museum Purchase, 1941-13.)

A Young Hussey Charging Old Toothless with an Imposibility, or the Cracked Pitcher (detail), published by R. Sayer and J. Bennett. London, England, 1778. Black-and-white etching and line engraving with period hand color. (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Museum Purchase, 1990-172.)

Egbert van der Poel, Barnyard Scene (detail), Netherlands, 1658. Oil on canvas. (Private collection; photo © Christie’s, Amsterdam.)

Penury, published by Peter del Pasquin, London, England, 1796. Black-and-white etching and line engraving with period hand color. (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Museum Purchase, 1964-64.)

Sauceboat, Staffordshire, England, ca. 1750. Slip-cast, white salt-glazed stoneware. H. 2 5/8". (Courtesy, Strawbery Banke, 1985.15; photo, Craig McDougal.) Excavated from the Hart-Shortridge House site in Portsmouth, New Hampshire.

Punch bowl, Jingdezhen, China, ca. 1780. Hard-paste porcelain. D. 11 1/4". (© Bristol Museums, Galleries & Archives.)

Base of the punch bowl illustrated in fig. 11. Inscribed by the china mender in low-fired iron gall ink under the foot: “Coombes / Queen Street / Bristol / 1802”

A Porcelain Mender (and detail), possibly by Puqua, Guangzhou, China, ca. 1790. Watercolor. 14 1/4" x 18 1/8". (© Victoria and Albert Museum.)

Bow drill with accessories, China, nineteenth century. Wood, iron, bronze, steel. (Private collection; photo, courtesy private collection.)

Plate, Bristol, England. Tin-glazed earthenware. D. 8 5/8". (Courtesy, Historic Deerfield, Inc.)

Detail of the thread repair on the back of the plate illustrated in fig. 15.

Threaded wire rivets on punch bowl fragments, Jingdezhen, China, ca. 1750. (Courtesy, Independence National Historical Park Collection. Photo courtesy of Deborah L. Miller and Robert Hunter.) Excavated in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Dish, Staffordshire, England, ca. 1760. White salt-glazed stoneware. L. 11 1/4". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Museum Purchase, 1976-115.)

Detail of the dish illustrated in fig. 18. Note the threaded wire rivet with holes filled with glue.

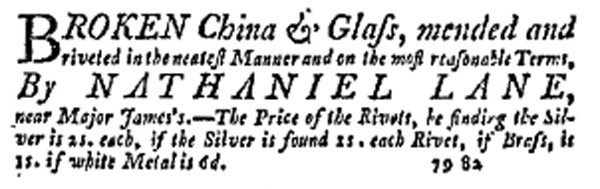

Advertisement, New York Journal, July 23, 1767. (Courtesy, American Antiquarian Society.) China and glass mender Nathaniel Lane itemized his prices for rivet repairs.

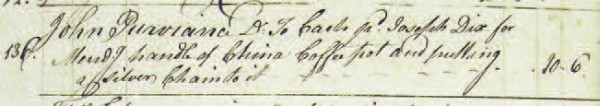

Entry from daybook kept by Philadelphia silversmith Thomas Shields, November 1, 1775. (Courtesy, The Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera, Henry Francis du Pont Winterthur Museum.)

Teapot, England, ca. 1810. Transfer-printed pearlware with tin replacement handle. H. 4". (Courtesy, Collection of Old Salem Museums & Gardens, Gift of Emil Shaffner, 837.1.)

Philippe Mercier (1689–1760), Portrait of a Young Woman Holding a Tea Tray, France, eighteenth century. Oil on canvas. 35 1/8" x 28". (Private collection; photo, © Christie’s Images / Bridgeman Art Library.) Note the teapot in the detail with a silver-tipped spout and wicker-wrapped replacement handle.

Teapot, Jingdezhen, China, ca. 1735. Hard-paste porcelain, silver replacement spout, chain, and mount for lid. H. 5 1/8". (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Gift of Murray Nimmo, 2013-143.)

Saucer, Jingdezhen, China, ca. 1780. Hard-paste porcelain. D. 5 3/4". (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Gift of Catha Grace Rambusch, 2013-22.) An arc-shaped chip on the rim was ground down and fitted with a piece from a different Chinese porcelain dish decorated en grisaille. The replaced piece is attached to the dish with three metal rivets—only the holes are visible on the face of the dish.

The victim of a robbery in Boston in 1773 placed an advertisement in a local paper offering a $10 reward to anyone who could help him regain his lost property. Listed between the engraved silver teaspoons and the fine “Cream-Pot of Pencil China” was “a pint blue & white China Mug that was crack’d and riveted.”[1] Despite its less-than-perfect condition, the mug was clearly a valued object to be included among the others in the ad.

The practice of mending ceramic objects could well be as old as the pottery-making tradition itself. The British Museum boasts objects with repairs dating back at least to the sixth century B.C.[2] The collection of Chinese porcelains in Topkapı Palace, Istanbul, includes pieces with repairs made during the medieval period to objects centuries older.[3] And archaeological excavations in the Middle East reveal fragments with evidence of rivet repairs found in eleventh-century Islamic-world contexts.[4] Repaired ceramic objects are not just relics of ancient and medieval antiquity, however. They are found in colonial and federal America as well, and can be traced through newspapers, inventories, account books, letters, intact objects in museum collections, and archaeological finds.

Looking at mended ceramics with modern eyes, it is easy to overlook the context in which the repairs were made. How did those objects break? Who repaired them? What methods did they use? And ultimately were they preserved as family heirlooms or disposed of, only to be found in later archaeological excavations? This article explores these questions with a particular focus on the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries in order to put broken and mended ceramics in historical context within the Anglo-American world (fig. 1).[5]

How Do Ceramics Break?

In the life of pottery and porcelain, breakage begins at the kiln; wasters are the ultimate proof, as any potter will lament. Sometimes there is evidence of repairs made to objects before they leave the kiln. It was probably in the leather-drying or air-drying stage that a piece of the rim of the plate illustrated in figure 2 was broken off and stuck back on or replaced by the Chinese potter before it was decorated and fired. A slip-decorated dish excavated in Kingsmill in Williamsburg, Virginia, reveals a similar repair. Perhaps made too thin in the initial object formation, the well of the dish cracked during the firing. The potter then used a different color slip to patch the dish before firing it a second time (fig. 3).

If the ceramics were fortunate enough to survive the kiln, they would then have to survive packing and shipment. Poor packers, rough seas, or a combination of the two frequently brought frustration or sorrow to eighteenth-century consumers.[6] George Washington, for one, found his shipments of white salt-glazed stoneware “incomplete with two things broke.”[7] Shipment was such a constant concern for Washington that he often ordered additional wares from his factors in England at the outset, anticipating breakage en route. He wrote one of his London factors, noting that, “The China came without any breakage, for which Reason I must counter order the addition to it desir[e]d in my last [letter].”[8] The arrival of an order of ceramics without at least a few broken dishes must have been an unexpected experience.

Although breakage seems to be more the exception than the rule overall, efforts were made by consumers to deter the destruction of their fragile purchases. In 1781, amid the height of battles during the American Revolution, Abigail Adams wrote from Boston to family acquaintance and fellow Bostonian James Lovell, who was residing in Philadelphia. Lovell had been instrumental in several successful naval skirmishes off the coast of Boston, and the outcome of those battles meant the possibility of securing shipment for some goods that Lovell had been holding for the Adamses. Aware of this, and understanding that goods traveling by sea rather than over land had a better chance of surviving intact, she wrote, “There may possibly be some opportunity opened by water for a safe conveyance of the articles about which you have already taken much trouble. If there should I would rather risk the Box of china that way than by land.”[9]

Breakage generally occurs either through human error or an act of nature. An example of the latter was documented in 1739, when the Virginia Gazette recorded a storm in Philadelphia: “On Sunday Night, about the Hour of Eleven, there was a very severe clap of Thunder . . . Which Struck the House of Andrew Hamilton, Esq. . . . [and] broke some China.”[10] Another account was recorded in the Marblehead, Massachusetts, home of the Reverend Barnard, which was struck by lightning that “came down the Side of the Chimney, tearing some of the Shingles of the Roof, and ran into the lower Room . . . it proceeded to a Closet, and broke some China Ware therein. . . . A bowl which stood in the Closet had a Hole through, the [size] of a Knitting-needle, occasioned by the lightning.”[11] In 1760 the South-Carolina Gazette published an eyewitness account of an earthquake in Brussels where, late one evening in January, the door bells of the city’s inhabitants started ringing “of themselves,” and the “china and glass ware, by striking together, were dashed to pieces.”[12]

Military actions can wreak havoc with ceramics. The Pennsylvania Gazette reported in 1745 that off the coast of Boston Harbor a naval engagement resulted in breaking all of one sailor’s “Glass and China Ware.”[13] And, of course, carelessness frequently resulted in broken ceramics. Satirist Jonathan Swift wrote in his tongue-in-cheek publication Directions to Servants, “When you carry a parcel of China plates, if you chance to fall, as it is a frequent misfortune, your excuse must be, that a dog ran across you in the hall, that a chamber-maid accidentally pushed the door against you, that a mop stood across the entry, and tript you up,” and the excuses go on.[14] But the important point to note for this thesis is that the occurrence of ceramic breakage was a “frequent misfortune,” the truth of which Swift eloquently expands in his spoof.

A cache of broken but nearly complete teawares excavated from the Garden Terrace outside the tea room at Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello may be the result of a cover-up by household servants when an entire serving tray was dropped.[15] Many eighteenth- and nineteenth-century prints depict startled footmen who end up with a dishpan full of fragments (fig. 4). Those “below stairs” were not the only ones to break dishes, however. Rowdy behavior at the dinner table and clumsiness at the tea table often resulted in broken dishes, well illustrated in numerous comedic graphics of the period (figs. 5-7).

The purposeful breaking of dishes could convey a moral or political statement. The Pennsylvania Gazette reported one memorable incident in March 1742:

[An eccentric Quaker named Benjamin Lay] bore a publick Testimony against the Vanity of Tea-drinking, by devoting to Destruction in the Market-place, a large Parcel of valuable China, &c. belonging to his deceased Wife. He mounted a Stall on which he had placed the Box of Ware; and when the People were gather’d round him, began to break it peacemeal with a Hammer; but was interrupted by the Populace, who overthrew him and his Box, to the Ground, and scrambling for the Sacrifice, carry’d off as much of it whole as they could get. Several would have purchas’d the China of him before he attempted to destroy it, but he refused to take any Price for it.[16]

The reaction stirred by Lay’s extreme behavior is not surprising as Chinese porcelain was a very expensive and a highly desired commodity.

To Repair or Not to Repair

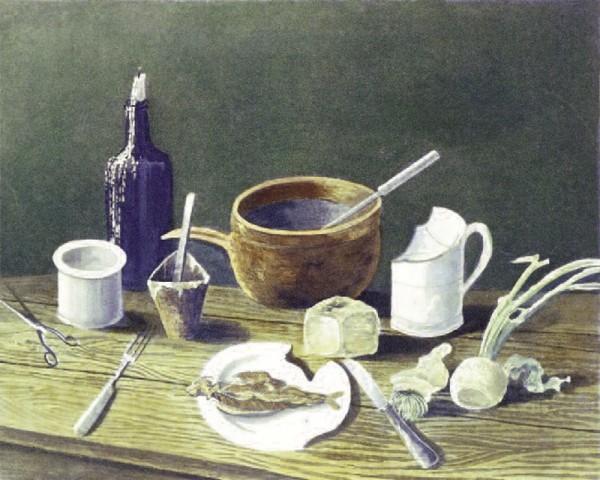

Whether broken by shipment, cataclysmic weather event, clumsy servant, rowdy guest, unsupervised children or animals, or impassioned religious or political zealots, the owner of the ill-fated ceramic object then had to decide whether to repair the dish or leave it broken. Even if it was left broken, however, either because the object was not valued enough to warrant repair or because the owner did not have the means to have it repaired, it could still find new life through repurposing—the eighteenth-century version of “reduce, reuse, recycle.” After all, a chipped slipware dish that once graced the corner cupboard or table could always find its way to the barnyard to hold chicken feed (fig. 8).

In his “Meditation on a quart mugg” Benjamin Franklin wrote that, instead of attempting to repair a shattered mug, its base could be used to serve other functions: “If thy Bottom-Part should chance to survive, it may be preserv’d to hold Bits of Candles, or Blacking for Shoes, or Salve for kibed Heels; but all thy other Members will be for ever buried in some miry Hole; or less carefully disposed of, so that little Children, who have not yet arrived to Acts of Cruelty, may gather them up to furnish out their Baby-Houses. . . .”[17]

If a broken object was not destined for repurposing and the owner could not afford to have it mended (fig. 9), it still did not necessarily follow that it was discarded. The penniless country schoolmaster was the subject of a poem that appeared in the Virginia Gazette in 1770. The poem describes the teacher’s fireplace mantel where “broken tea cups, wisely kept for show, Rang’d o’re the chimney, glist’ned in a row,” confirming that broken dishes had value for display if they were no longer serviceable on the table.[18]

The Mender and the Method

If the eighteenth- or early-nineteenth-century owner did decide to repair the broken object in question, several options were available. One was that the owner could personally repair the piece. Numerous English receipt books and housewifery publications included recipes for china glues and East India pastes. Colonial American publications offered similar formulas. Hutchin’s Improved Almanac, published in New York, issued a recipe for “an Exceeding fine Cement to mend broken China or Glasses.” The recipe came with the guarantee to be “very useful to all Families” and able to be mixed and applied “with the greatest Ease.”[19] Although one could wonder about the smell, the recipe calls for “Garlick stamped in a stone Mortar; the Juice whereof, when applied to the Pieces to be joined together, is the finest and strongest Cement for that Purpose.”[20]

Another almanac offered a recipe for the “Chinese method of mending China” that was likely less pungent than the one offered by Hutchins but more labor intensive to mix: “Boil a piece of white flint-glass in river water 5 or 6 minutes; beat it to fine powder, and grind it well with the white of an egg, and it joins China . . . so that no art can break it again in the same place.”[21]

In addition to making one’s own concoction from a prescribed receipt, the owner of the broken ceramic object could purchase a glue or paste from merchants, craftsmen, and dry-goods sellers. The South-Carolina Gazette for June 18, 1763, advertised just such a product. Benjamin Hawes of Charleston offered for sale and newly imported from London, “a fine cement for joining of china or glass.”[22] In similar fashion up the East Coast, Anthony Lamb, a mathematical instrument maker, advertised in the Connecticut Journal in 1779 that he had for sale “Putty for mending China.”[23] A New York paper posted in the same year an ad for “INDIA GLUE” that possessed “strength superior to any thing of the kind for mending ornamented China, even basins for common use.”[24]

Archaeologically recovered ceramics fragments sometimes bear evidence of the use of china glues and pastes. At least one fragment unearthed at the Anderson site in Williamsburg, Virginia, confirms a glue repair to a saucer or small dish.[25] Recent excavations at George Washington’s Ferry Farm have found numerous damaged creamware tea- and punch wares associated with Mary Washington’s tenure that were mended with glue repairs.[26]

The white salt-glazed stoneware sauceboat illustrated in figure 10 was mended using another eighteenth-century type of glue repair, this one recovered at a house site in Portsmouth, New Hampshire. The substance used to fix the break in the lip was made with what tested to be white lead house paint.[27] This appears to have been a common method for repairing ceramics in the eighteenth century. Probate inventories show other ceramics glued using the same technique. The inventory taken at the death of Richard Mitchell of Lancaster County, Virginia, for example, lists in the Dairy “2 Earthen [dishes] Stuck with White Lead.”[28]

Newspapers and trade cards reveal that the owner of a broken dish could easily find a trained craftsman to assist in the repair. As early as 1725 American newspapers endorsed the skills of craftsmen like Robert Phillips, who set up shop in Boston, where he “cement[ed] China, Glass, or Delf.”[29] He may have picked up his ceramic cementing techniques from potters in Liverpool, the city from which he proudly hailed.[30] England had a thriving business of China menders in the eighteenth century. Trade cards for people such as Edmund Morris of London advertised mending “all sorts of China Wares with a Peculiar Art . . . so as a Rivetted Piece of China will do as much Service as when New.”[31] Morris also touted his methods for mending china in newspapers and boasted that he mended pieces for nobility in addition to selling repaired pieces at low cost. China burner and mender Edward Coombs of Bristol, England, not only promoted his skills on trade cards and in newspapers but also signed some of the pieces he repaired (figs. 11, 12).

On both sides of the Atlantic the types of repairs fell within three broad groups: the object was stuck back together through the use of some paste or glue, as evidenced by the white salt-glazed stoneware sauceboat and the multiple recipes for pastes previously mentioned; it was riveted together with various materials; or it was fastened together with some kind of binding. Additionally, many repairers advertised the ability to restore an object’s usefulness when a piece of it was missing, for example a mug without a handle, a teapot without a spout, or a bowl without a piece of its rim. Almost every mender described his methods as unique or new and improved. But their techniques were often rooted in much older traditions derived from early cultures.

The Chinese wrote down recipes for porcelain glues at least as early as the seventeenth century and the recipes at that time were purported to be ancient.[32] The Chinese had also practiced the art of riveting for centuries. Riveting required great hand skill. A piece was typically tied together, as seen in figure 13, then a drill was used to pierce holes on either side of the crack. The holes had to be offset approximately fifteen to twenty degrees so that the pressure placed on the object from the rivet would actually hold the broken parts together and not cause further stress on the piece or the repair.[33] A bow drill (fig. 14) was often the tool of choice for creating such holes. The little dish illustrated in figure 14 was used to warm the metal rivets in order to make them flexible and able to be bent and inserted into the holes. The heated metal rivets or staples would then contract as they cooled, gripping the two pieces of the object together as one.

Repair techniques similar to those used in China were implemented throughout the colonies and England. James Walker from London advertised in Parker’s New York Gazette and Post Boy that he repaired pieces “in the same Manner as done in the East-Indies.” But he also added his own signature to certain repairs, stating that he performed “a new and neat Method of riming and Sewing China.”[34] Exactly what this sewing entailed is a mystery, but the Bristol tin-glazed earthenware plate illustrated in figure 15 is an example of the so-called sewing china technique, which is perhaps the service Walker offered.[35] The dish is bound together with a cotton thread or twine woven between alternating holes that have been drilled through the object in the same manner that would have been carried out prior to the insertion of metal rivets. In the place of the usual metal staples, however, cotton twine was laced between the holes and knotted on the reverse of the dish with a strong double overhand knot (fig. 16).[36] James Walker’s sewing technique might also have referred to sewing with wire. Fragments of Chinese porcelain found in an eighteenth-century archaeological context in Philadelphia exhibit threaded wire rivets made by lacing thin-gauge wire multiple times through alternating holes until the desired stability was reached (fig. 17).[37] This was an extremely common practice in the eighteenth century, although it does not always survive belowground. The repairs made using this method usually were further strengthened by filling the holes with glue (figs. 18-19).

There were many different methods for repairing pieces, and various china menders on both sides of the ocean advertised their skills and assured their work. But in addition to promising that their repairs would hold, many china menders guaranteed their methods to be reasonably priced. The cost of repairs varied depending on the type of repair and materials used. Nathaniel Lane, a china and glass mender from New York who had a thriving business in the 1760s, advertised the price of riveting according to the type of metal used and how it was supplied (fig. 20). If he provided the silver for a rivet, it cost two shillings; if the customer provided the silver, it cost one shilling. If the rivet was made of brass, it also cost one shilling. And if it was made of white metal—a period term for pewter—the rivet cost six pence.[38]

George Beattie, a Londoner who set up shop in Boston, promised his Massachusetts clients that he, too, would mend their broken china as reasonably as in London.[39] The prices of colonial China menders were comparable to the cost of services offered to London residents. London china riveter James Harris left a rare bill of sale on the reverse of his trade card.[40] For a repair made in 1770 he charged one shilling for two rivets. Unfortunately it is unclear whether the cost was for silver or brass, since he offered repairs in both.

For some individuals the business of mending ceramics was their sole occupation, or at least their primary advertised occupation. For others the business of china repair was a logical supplementary service offered to their customers. James Rutherford in Charleston, South Carolina, for example, advertised himself as a “regular-bred gold and silver smith . . . who . . . likewise works in jewelry, and clasps broken china in the neatest manner.”[41] James Proby, also from Charleston, ran a scrap metal and tinsmith business in the 1760s and advertised “mending China, at the lowest Rates, and quickest Dispatch.”[42]

Silversmiths in Philadelphia and Boston mended dishes as well. Surviving daybooks for Philadelphia silversmith Thomas Shields and Boston silversmith Paul Revere record numerous instances of repairing china dishes. With the exception of rimming a silver punch bowl, most of Revere’s ceramic mends seemed to incorporate the use of silver rivets.[43] In addition to riveting numerous dishes, Shields occasionally mended porcelain coffeepot and teapot handles and covers. Sometimes he added a chain from the cover to the spout, perhaps in an attempt to prevent the cover from dropping off the object and incurring further damage (fig. 21).[44]

Tinsmiths also repaired ceramic objects. Virginia tinsmith John Beale, for example, advertised that, in addition to making and mending copper and tin objects, he repaired broken dishes.[45] Owned by Christina Spach when she was a child, the miniature teapot illustrated in figure 22 retains a history of having been repaired by tinsmith Philip Reich in Salem, North Carolina.[46] The teapot’s missing ceramic handle was replaced with a handle composed of four pieces of tin. One piece wraps the foot, another encircles the rim, a third loops around the spout and connects to the piece at the foot, and a fourth crimped strip makes the handle, the crimping encasing and hiding wire for added stability.

The ceramic repair business was not the exclusive domain of men, however. Mrs. Barbary Opperman had a china repair business out of a Philadelphia tailor’s shop.[47] Elizabeth Flagg, a widow in Boston, advertised in 1795 that she and her daughters “rivet[ed] and mend[ed] china and glass, and Needlework of all kinds, at their house. . . .”[48] Approximately ten months later Flagg placed another advertisement in the paper that revealed her progress and an unexpected problem: not all of her clients were collecting their mended wares. She stated that she had “a number of Pieces of repair’d China in her Possession,” which she requested be picked up by their owners.[49] Maria Warwell was another female china mender. She set up what she initially thought would be a temporary business in Charleston. She and her husband were intending to leave South Carolina, so while awaiting passage she took up work “mending in the neatest and most durable manner, all sorts of useful and ornamental china, viz. beakers, tureens, jars, vases, bust’s.” She did not use rivets but employed the use of a type of china putty so that when a piece of an object was missing she could “substitute a composition in its room and copy the pattern as neigh as possible.”[50]

The Fate of Mended Ceramics

Throughout history the fate of the mended ceramic object has frequently been decided based on the object’s usefulness, beauty, rarity, or a combination of all three. The way in which the owner or society qualified those characteristics defined the object’s monetary value and intrinsic worth. Despite their condition, mended ceramics could still be used to convey status. For example, one husband bemoaned:

I am never allowed to eat from anything better than a Delft plate, that the economy of the beaufait, which is embellished with a variety of China, may not be disarranged and indeed my wife prides herself particularly on her ingenious contrivance in the article, having ranged among the rest some old China not fit for use, but disposed in such a manner, as to conceal the streaks of white paint that cement the broken pieces together.[51]

Repaired and broken ceramics were often kept in the china closet or bowfat. The highly regarded Chinese porcelain carefully arranged in the bowfat enabled the inhabitants of the house to display their wealth, even if some of the objects were no longer functional. When intact dishes were removed for dining, the mended ones could remain, proudly suggesting to visitors that there was more wealth in the cupboard. This mind-set is further substantiated in the room-by-room inventories of prominent Virginians. The dining room of a Richmond County gentleman recorded, “in the Buffet [bowfat] / 1/2 Dozen Coffee Cups some crack’d and 2 of them without handles.”[52] These broken ceramics were scattered amid the fine porcelain, glass, and silver listed in the same space. The probate inventory taken at the death of Thomas Nelson of Yorktown, Virginia, also listed broken ceramics in the dining room, including several punch bowls.[53]

The practice of spring cleaning was the subject of an account related in a Pennsylvania newspaper in 1785. Everything had to be removed from the house so that it could be scrubbed and whitewashed from the garret to the cellar. Off the kitchen “a closet has disgorged its bowels” and revealed the contents: “riveted plates and dishes, halves of China bowls, cracked tumblers, broken wine glasses . . . handfuls of old corks, tops of teapots, and stoppers from departed decanters.”[54] Whether for storage or display, the broken and mended objects were crammed into the closet.

Repairs to objects like teapots could enable them to return to service on the tea table, and repairs made of precious metals served the dual purpose of restoring the objects’ usefulness while also enhancing their value and beauty. Some china menders offered to replace broken or faulty teapot spouts with silver replacements, often guaranteeing that the new spout would perform better than the original ceramic one, that is, not drip (fig. 23).[55] The fifty-plus-page probate for wealthy Virginian Robert “King” Carter of Corotoman, which was taken in 1733, listed among numerous objects “1 ditto [Chaney or china] Teapott with a Silver Spout.”[56] The teapot, the whereabouts of which are unknown, could have been similar to the one illustrated in figure 24.

Conclusion

The tradition of mending ceramics is a long and interwoven story of value and worth, both sentimental and monetary. For example, the Japanese art of kintsugi—repairing ceramics with gold lacquer fill—has been practiced for centuries. This method of repair raises the humble teabowl from a utilitarian object to a revered work of art.

In 1857 Philadelphia hosted the Convention of Earthenware Dealers, where a gentleman from New York praised those in attendance and lauded the array of utilitarian and ornamental objects represented at the forum. He concluded his oration with the hopeful exclamation, “May we never break!”[57] His remarks referenced not only the camaraderie of the assembled audience but also the fragile stuff of their trade.

Indeed, today we often admire ceramic objects with old repairs. In recent years there has been a surge of interest among conservators and restorers to better understand repairs, recognizing their part in an object’s history.[58] Mends and repairs can be beautiful, enhancing the otherwise ubiquitous cup or plate; they can also border on the bizarre, elevating it to the level of an “object of curiosity” (fig. 25). When such objects are viewed today they should remind us of the context in which those repairs were made for individuals who had particular reasons for retaining their fragile, imperfect wares.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I am grateful to many people for their assistance, support, and/or encouragement. Particular thanks go to Johanna M. Brown, Suzanne Findlen Hood, Robert Hunter, Amanda E. Lange, Nick Luccketti, Debbie Miller, Merry Outlaw, William R. Sargent, Janine E. Skerry, and my parents. “May we never break!” Also my appreciation to Andrew Baseman, for having attended my first lecture on mended ceramics. His blog Past Imperfect is an invaluable resource.

Boston News-Letter, August 12, 1773, p. 2. “Pencil China” probably refers to porcelain decorated en grisaille.

Nigel Williams, Porcelain Repair and Restoration: A Handbook (1983; new ed., London: British Museum, 2002), pp. 12–13.

Regina Krahl, Chinese Ceramics in the Topkapı Saray Museum, Istanbul: A Complete Catalogue, 3 vols. (London: Sotheby’s Publications, in association with the Directorate of the Topkapı Saray Museum, 1986), 1:297, no. 226a; 2:513, no. 603; 2:540, no. 652; 2:584, no. 790; 2:591, no. 817; and 2:592, no. 819.

Marcus Milwright, “Prologues and Epilogues in Islamic Ceramics: Clays, Repairs, and Secondary Use,” Medieval Pottery 25 (2001): 72–83.

While many articles have discussed mended ceramics to some extent, the author is aware of only three published prior to this volume of Ceramics in America that specifically focus on the topic in American contexts. Although somewhat dated, these works are: Stanley A. South, “Archaeological Evidence of Pottery Repairing,” in The Conference on Historic Site Archaeology Papers 1967, 2 vols. (Raleigh, N.C.: Conference on Historic Site Archaeology, 1968), 2:62–71; Dwight P. Lanmon, “Putting the Pieces Together: Ceramics and Glass Repairing in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries,” Delaware Antiques Show (1969): 95–102; Bradford L. Rauschenberg, “Ceramic Menders and Decorators in Charleston, South Carolina, before 1820,” Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts 17, no. 2 (November 1991): 115–27.

For more on packing and shipping ceramics and the sometimes unsuccessful journeys of the wares, see Janine E. Skerry, “‘A Tierce of Stone and Earthen Ware’: Packing Ceramics for Shipment to America,” in This Blessed Plot, This Earth: English Pottery Studies in Honour of Jonathan Horne, edited by Amanda Dunsmore (London: Paul Holberton Pub., 2011), pp. 172–80.

“From George Washington to Thomas Knox, January 1758,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/02-05-02-0060. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Colonial Series, vol. 5, 5 October 1757–3 September 1758, ed. W. W. Abbot. (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1988), pp. 87–88.]

“From George Washington to Richard Washington, 18 March 1758,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/02-05-02-0078. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Colonial Series, vol. 5, 5 October 1757–3 September 1758, ed. W. W. Abbot. (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1988), pp. 105–6.]

“Abigail Adams to James Lovell, 15 November 1781,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/04-04-02-0164. [Original source: The Adams Papers, Adams Family Correspondence, vol. 4, October 1780–September 1782, ed. L. H. Butterfield and Marc Friedlaender (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1973), pp. 244–45.]

Virginia Gazette, June 22, 1739, p. 2.

Pennsylvania Gazette, August 25, 1763, p. 1.

South-Carolina Gazette, May 10, 1760, p. 1.

Pennsylvania Gazette, July 4, 1745, p. 2. It is amusing to note that the same article reported the deaths of seven men, but the glass and china were listed first.

Jonathan Swift, Directions to Servants in General (London: Printed for R. Dodsley and M. Cooper, 1745), pp. 61–62.

John Metz, Archaeological Investigation of the Garden Terrace, Kitchen Dependency and Corner Terraces, Monticello Archaeology Report, November 2000; and Suzanne Findlen Hood, “China of the Most Fashionable Sort: Chinese Export Porcelain in Colonial America,” lecture, New York Ceramics Fair, January 2013.

Pennsylvania Gazette, March 25, 1742, p. 3. Some may recall similar activity during World War II, when some Americans broke their Japanese porcelain in the streets as a statement against the bombing of Pearl Harbor. See Otto Friedrich, City of Nets: A Portrait of Hollywood in the 1940s (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986), p. 116.

Benjamin Franklin, “Meditation on a quart mugg,” Pennsylvania Gazette, July 19, 1733.

Virginia Gazette, October 25, 1770, p. 4.

John Nathan Hutchins, Hutchin’s Improved: Being an Almanack and Ephemeris of the . . . Year of Our Lord, 1769 (New York: Printed and sold by Hugh Gaine, at the Bible and Crown, in Hanover Square, 1769), p. 9.

Ibid. For further discussion of period glues, see Mara Kaktins, Melanie Marquis, Ruth Ann Armitage, and Daniel Fraser, “Mary Washington’s Mended Ceramics: A Study of Eighteenth-Century Glues,” in this volume.

Benjamin West and Nathan Daboll, The North-American Calendar: or, The Rhode-Island Almanack, for the Year of Our Lord Christ 1788 (Providence, R.I.: Printed by Bennett Wheeler, 1787), p. 17.

South-Carolina Gazette, June 18, 1763, p. 1.

Connecticut Journal, June 16, 1779, p. 1.

Royal Gazette (New York), October 16, 1779, p. 3.

Fragment excavated from the Anderson site, 1790–1810 context.

For more on this, see Kaktins et al., “Mary Washington’s Mended Ceramics: A Study of Eighteenth-Century Glues,” in this volume.

Janine E. Skerry and Suzanne Findlen Hood, Salt-glazed Stoneware in Early America (Williamsburg, Va.: Colonial Williamsburg, 2009), pp. 145–46.

Inventory for Richard Mitchell, December 20, 1781, Lancaster County Deeds and Wills, number 20, pp. 213a–219.

New England Courant (Boston), May 17–24, 1725, p. 3.

Ibid.

Edmund Morris Trade Card, 1740–1760, © Trustees of the British Museum.

Williams, Porcelain Repair and Restoration, pp. 13–14.

Ibid., pp. 16–19.

Parker’s New York Gazette and Post Boy, November 20, 1760, p. 3.

Amanda Lange, Delftware at Historic Deerfield, 1600–1800 (Deerfield, Mass.: Historic Deerfield, 2001), p. 74.

Ibid., and author’s conversation with Colonial Williamsburg Foundation textile curator Linda Baumgarten, January 19, 2013, who identified the type of knot used.

Email correspondence between the author and Debbie Miller, January 20, 2013.

New York Journal, July 23, 1767.

Boston Post-Boy, August 18, 1766, p. 3.

James Harris Trade Card, ca. 1770, © Trustees of the British Museum.

South-Carolina Gazette, March 16, 1752, p. 4.

South-Carolina Gazette, July 1, 1766, p. 2.

Paul Revere Waste and Memorandum Books, entry for Captain William Torrey, “Riming a China Punch Bowl w/ Silver,” September 12, 1762, Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston, Massachusetts.

Thomas Shields Daybook, 1775–1791, The Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera, Henry Francis du Pont Winterthur Museum, Winterthur, Delaware.

Thomas Shields Daybook, 1775–1791, The Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera, Henry Francis du Pont Winterthur Museum, Winterthur, Delaware.

According to the object file at Old Salem Museums & Gardens (acc. no. 837.1), Christina Spach married Salem, North Carolina, silversmith John Vogler in 1819. Since John Vogler was a skilled metalsmith, it is also possible that he crafted the replacement handle.

Pennsylvania Gazette, July 17, 1766, p. 5.

Columbian Centinel, Boston, April 15, 1795, p. 3.

Boston Gazette and Weekly Republican Journal, February 1, 1796, p. 3.

South-Carolina Gazette and Country Journal, July 28, 1767, p. 4.

The Connoisseur, vol. 3 (London, 1757).

Inventory for Daniel Hornby, April 11, 1750, Richmond County Wills No. 5, pp. 670–73.

Inventory for General Thomas Nelson, June 2, 1789, York County Wills and Inventories No. 23, pp. 181–83.

Pennsylvania Packet and Daily Advertiser, June 18, 1785, p. 2.

Edward Coombs China Burner and Mender Trade Card, Bristol Museums, Galleries & Archives. On that trade card, Edward Coombs advertises, “Tea Pots that pours indifferently, may be made to pour smoothly by tipping them neatly with Silver, otherwise by taking off their own Spouts and substituting new ones of Silver or any other Metal.”

Transcription of the inventory of Robert Carter’s Estate, 1733, available online at http://carter.lib.virginia.edu/html/C33inven.mod.html.

The Sun (Baltimore, Md.), June 27, 1857, p. 1. For the entire speech, see Robert Hunter and Oliver Mueller-Heubach, “The Captain George W. Russell Presentation Pitchers,” in this volume.

Stephen Koob, “Obsolete Fill Materials Found on Ceramics,” Journal of the American Institute for Conservation 37, no. 1 (1998): 49–67; and Isabelle Garachon, “From Mender to Restorer: Some Aspects of the History of Ceramic Repair,” in Glass & Ceramics Conservation (International Council of Museums, 2010), pp. 22–31.