Punch bowl, probably Derby, England, 1765–1772. Creamware. D. 6". (Courtesy, The George Washington Foundation; photo, John Earl.) Decorated with distinctive overglaze enamels, this bowl was recovered from the cellar of the Washington house.

Punch bowl, probably Derby, England, 1765–1772. Creamware. D. 6 1/4". (Courtesy, Kimberley Overman; photo, Zac Cunningham.)

Cross section of the base of the bowl illustrated in fig. 1. (Courtesy, The George Washington Foundation; photo, John Earl.) Glue residue is clearly visible on the edges of the break.

Microscopic view of glue residue on the bowl illustrated in fig. 1. (Courtesy, Dovetail Cultural Resources Group.)

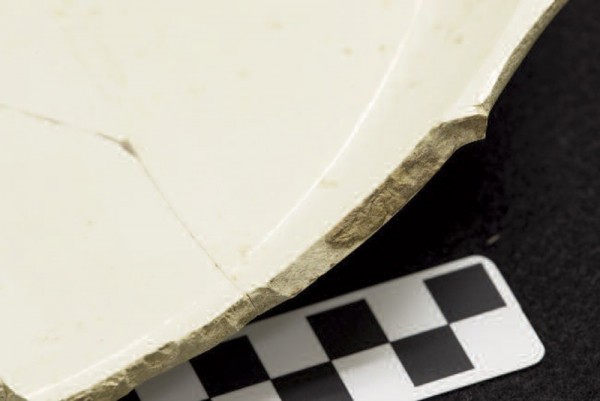

Close-up of a platter fragment, England, 1765–1772. Creamware. (Courtesy, The George Washington Foundation; photo, Zac Cunningham.)

Close-up of a teapot lid, England, 1765–1772. Creamware. (Courtesy, The George Washington Foundation; photo, Zac Cunningham.)

Close-up of plate rim fragment, 1750–1760. White salt-glazed stoneware. (Courtesy, The George Washington Foundation; photo, Zac Cunningham.)

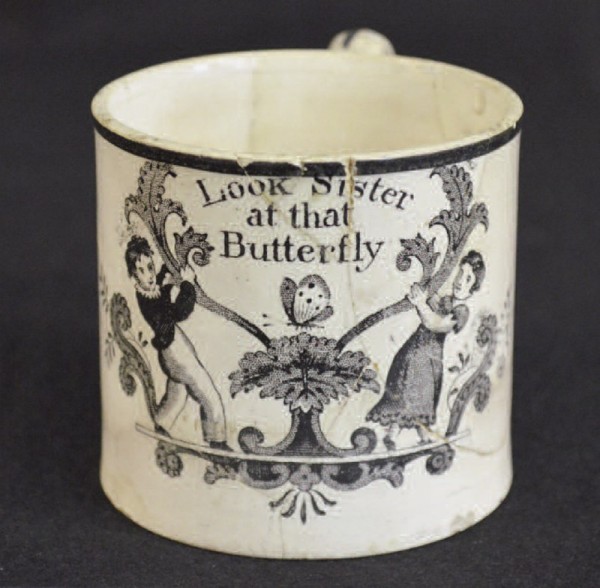

Mug, England, ca. 1820. Pearlware. H. 2 3/8". (Courtesy, Laura Galke; photo, Zac Cunningham.) Antique mug mended using historic glue recipe.

Archaeologists interpret human lives using broken, cast-off, lost, or abandoned items. In today’s world of mass production and disposable material culture, we sometimes forget the value objects had to people in past generations. It is generally assumed that broken items were discarded immediately. Those who study ceramics, however, know better. Even with this knowledge, archaeologists at George Washington’s boyhood home, Ferry Farm, were surprised when a substance resembling glue was noted on fragments of an archaeologically recovered creamware punch bowl and other vessels from a context definitively associated with Mary Washington and her family.

To date, fragments of seven distinct vessels from the Washingtons’ time at Ferry Farm have been found that show repair using adhesives. This reveals an attitude toward repairing damaged objects, a specific activity taking place in the Washington household that was previously unknown and not documented in the historical record. Given that every aspect of George Washington’s life has been studied in great detail, with books written on the subject numbering in the thousands, this seems notable. The discovery of these residues has prompted several questions: Are the same glues present on all of the fragments? What is the composition of the glues? Was the mending done professionally or by a resident on the property? Were the mended vessels functional after their repair or used only for display?

Unfortunately, the use of historic glues on ceramics remains poorly documented and archaeological research on this sticky subject is scarce. Hence, we attempted to immerse ourselves in all things glue-related, which often took us into the unfamiliar waters of carpentry, art restoration, and book binding.[1] Chemistry played a large role in our analysis, as did experimental archaeology: intensive document research yielded eighteenth-century adhesive recipes, which we subsequently reproduced and used to mend modern ceramics in an attempt to better understand the properties and effectiveness of the various glues. Our research ultimately led to a better understanding of how and why the Washingtons and their contemporaries might have been repairing their ceramics in this fashion.

Background

Located across the Rappahannock River from Fredericksburg, Virginia, Ferry Farm was home to the Washington family from 1738 to 1772. The progenitor of the family, Augustine Washington, died in 1743, leaving a will that divided his property among his sons, with Ferry Farm going to George.[2] Augustine’s widow, Mary Ball Washington, never remarried. She and her children remained on the plantation, farming it with slaves until she moved to nearby Fredericksburg in 1772. The property, now owned by The George Washington Foundation, has been the focus of intensive archaeological study since 2001 under the supervision of chief archaeologist David Muraca.[3] Excavations concentrated on the site of the Washington house and its associated outbuildings have yielded an assemblage of more than 750,000 artifacts. This collection includes tens of thousands of fragments of ceramic tea- and tablewares from Mary Washington’s household that include creamware, Chinese porcelain, and white salt-glazed vessels.

The stone-lined cellar of the Washington house contained three fill episodes. The earliest deposit dates to when the cellar was in use from 1728 to about 1770. The second fill layers were deposited at the time the Washington family was leaving the site (the property sold in 1774). After that, the cellar was abandoned and the primary deposits were capped after the last fill episode took place when the house was torn down, circa 1830.[4]

The discovery of glue residues began when a creamware punch bowl, decorated with an enameled floral motif accented with cherries, was unearthed in the main basement of the house (fig. 1). The punch bowl and the majority of the other subsequently identified glue-repaired vessels were found in the second fill episode, when the family presumably was discarding household items in anticipation of their leaving. Additional creamware examples with similar floral motifs and an identical color palette to that of the punch bowl were recovered from another sealed cellar, located under the hall portion of the house.

The English-made punch bowl is thought to have been manufactured between 1765 and 1772. Parallel antique creamware forms with cherry designs in the same palette have similar date ranges.[5] This small punch bowl, known as a “sneaker,” would have been passed around from person to person at social gatherings with punch being consumed directly from it.[6] A privately owned intact creamware punch bowl (fig. 2) examined by archaeology staff at Ferry Farm reveals marked similarities to the Washington punch bowl.[7] Color palette choice (red, black, green, and yellow), stylistic qualities, design placement, as well as corresponding individual motifs on the bowls (for example, roses, buds, flowers, stems, leaves, and cherries), appear on both examples. Analysis of these elements attributes the manufacture of the bowls to the Cockpit Hill Pottery in Derbyshire, Derby.[8]

Based on its interior wear patterns, the archaeologically recovered punch bowl appears to have been used extensively before being broken into at least four fragments. It was mended with glue before a presumed second breakage episode and its eventual discard. The glue residue can be seen as a light brown substance adhering to the broken edges of the vessel along what was clearly the original breakage pattern (fig. 3). There is a substantial amount of glue on the interior of the vessel as well. Microscopic examination confirms that the residues are not simply organic deposits, which are common in some depositional environments but have not been seen archaeologically at Ferry Farm. Moreover, the interior glue on the punch bowl appears to exhibit brushstrokes from the application of the adhesive (fig. 4). These deep striations, which run parallel to each other and extend across adjacent sherds, are very apparent, but there is no indication of use wear on the surface of the glue, indicating that the vessel was not utilized post-mending.

Following this initial discovery, we examined other ceramic fragments dating from Mary Washington’s occupation of Ferry Farm. To date, at least seven additional vessels associated with the Washington family have been found to exhibit glue repairs. These include a creamware platter and plate, an enameled creamware teapot lid, white salt-glazed examples including molded plate rims and a hollow-ware base, and a fragment of a Chinese porcelain bowl with an Imari palette (figs. 5-7). With the exception of the white salt-glazed plate fragment, which was recovered from a shovel test pit near the cellar in an early archaeological exploration, all examples exhibiting glue residues were recovered from the Washington house cellar.

Glues and Mending in the Written Record

A review of historical documents as well as dialogue with colleagues indicate that evidence of repaired vessels is not uncommon archaeologically. Yet literature within the field, especially with regard to the use of adhesives, is lacking, although it should be noted that very recently a number of scholars have begun researching this subject.[9]

It is understood that people have been producing mastics for various purposes—including mending ceramics—for thousands of years. Adhesives that contain bitumen and birch tars used to haft stone points have been found on archaeological materials dating as early as the Paleolithic period.[10] The earliest recorded pottery-mending techniques in prehistoric times involved drilling holes on either side of the break and lashing the pieces together with hide strips or plant fibers. Often this method was combined with a plant- or animal-based glue to further seal the break.[11] Ceramic menders have been performing this service for thousands of years. China menders often utilized metal rivets when making repairs, carefully drilling holes in the vessels and stabilizing or rejoining them with adhesive.[12]

A professional mender seems to have been readily available to Mary Washington, although there is no record that she used his services. A goldsmith operating in the 1760s and 1770s in Fredericksburg, just across the river from Ferry Farm, also engaged in china mending. While he did not mention this service in his advertisements, he is listed in an account book belonging to George Weedon as having mended “China Bowls.”[13] To date, no artifacts excavated at Ferry Farm show any evidence of having been professionally mended with drill holes, metal hardware, or filling. Presumably Mary Washington chose the thriftier option of using homemade glues.

Eighteenth- and nineteenth-century all-purpose handbooks, cookbooks, and encyclopedias contain a multitude of glue and cement recipes, the examples of which are too numerous to list here. The “receipts,” or recipes, range in difficulty from very simple and easily executable to extremely complicated. It is implied in most of this literature that these recipes can be made in a domestic setting and are effective enough to produce viable vessels from broken fragments. With the advent of synthetic glues and increasing access to inexpensive tablewares in the twentieth century, the need for professional china menders waned, and the concept of mixing one’s own glue at home faded from memory—that is, until enterprising archaeologists and chemists combined their skills to resurrect the glue recipes of old.

Experimental Archaeology

To gain more insight into the practice of historic ceramic repair, Ferry Farm archaeologists attempted to replicate a number of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century home glue recipes and subsequently assessed their effectiveness. To date, three basic glue types found in the period literature have been replicated: cheese, hide, and resin. Samples were sent to chemist Ruth Ann Armitage of Eastern Michigan University and chemist Daniel Fraser of Lourdes University for chemical characterization. Such analysis would provide comparative data for similar studies conducted on the archaeological residues, which will be discussed later.

The initial difficulty of replicating the historic glues lay in obtaining all of the necessary ingredients. The materials for the glues included various mastics and gums, beeswax, brandy, cheese, duck eggs, garlic, isinglass (a gelatin derived from the air bladders of fish), ox gall, pickling lime, and our own tar created from pine resin, to name a few. Some recipes had to be rejected due to our inability to easily obtain items such as bull’s blood and the “white slime of large snails.”[14]

Cheese glue was the first to be reproduced. Based on a recipe published in The Scots Magazine in 1765, it involved only three ingredients: grated hard cheese, milk, and pickling lime.[15] The original type of cheese called for was “Suffolk Cheese,” the cheese equivalent of hardtack and eaten primarily by sailors in the British Navy; those who consumed it at the time complained bitterly of its taste.[16] Suffolk Cheese, as it existed in the eighteenth century, is now thankfully extinct, so a shredded block of dried Romano cheese had to be substituted. Our initial attempt at replicating this glue resulted in a lumpy, foul-smelling concoction that set too quickly (within minutes) for efficient mending and was somewhat caustic, partially removing the outer layer of skin on our hands. With slight alterations to measurements and minor substitutions gleaned from similar recipes (such as substituting egg whites for milk), subsequent iterations of this glue produced a much-improved adhesive that effectively mends ceramics.

Two hide-based recipes were reproduced, both taken from Handmaid to the Arts, an all-purpose guide for housewives published in 1764.[17] The first one was fairly simple, containing dried chips of basic glue rendered from animal hide and combined with brandy and quicklime. This resulted in a functional adhesive. The second glue was much more complicated—using hide, brandy, garlic juice, ox gall, various resins, vinegar, quicklime, and isinglass—but was by far the most effective in terms of its ease of application, the strength of the repair, and its relatively inconspicuous nature. As a result, we chose to use it to mend a pearlware child’s mug owned by a member of our staff (fig. 8) and, as of this writing, the glue has held for more than three years with no signs of deterioration.

The last glue reproduced was a resin glue recipe taken from The Encyclopædia Britannica: A Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, and General Literature (1888).[18] The recipe calls for only three ingredients: beeswax, resin (although the exact type was not specified), and quicklime. It became apparent as our research progressed that many of the recipes presumed a certain knowledge of ingredients and technique: we manufactured the tar from readily available pine resin, which proved a difficult and somewhat dangerously flammable endeavor. The resulting glue was almost impossible to work with and was too dark to be applied with any subtlety on white-bodied wares such as those Mary Washington was mending. However, it is entirely possible that lighter plant materials, such as sandarac and gum Arabic, were utilized in her day.

To ascertain the properties and functionality of our reproduced glues we obtained ceramics at a local thrift store to be broken and mended. This selection was purposeful in order to simulate the efficacy of our historic glue recipes on differing ware types with porosities similar to those of historic ceramics. Each vessel was dropped on a wide-planked wooden floor to replicate likely breakage conditions and mended with one of the experimental glues. Initially, our primary interest was simply in how effectively the glues mended a vessel. Although all of the glues functioned to some extent, the resin glue proved difficult to apply and did not produce many finished products worthy of subsequent use or even display. The hide and cheese glues, however, mended all ceramics well, with only a minimal amount of glue visible on the breaks after they had dried. Moreover, they were easy to apply with a paintbrush.

After drying, the mended vessels underwent experimentation to see how well they withstood the tests of burial, temperature, humidity, pressure, and liquid retention—all simulations designed to replicate the likely use and discard of ceramics during the colonial period. Some vessels were buried in the back dirt pile on our archaeological site for six months to determine how post-depositional processes affected the glue. The results were surprising. The resin glue had altered significantly in color and texture, turning from almost black to a medium brown, and was subject to bubbling and embrittlement or flaking from the broken edges of the vessel. The cheese glues remained cemented to the edges of the vessels after burial and changed from a white color to a mottled gray. Of all the glues, the cheese glue appeared to be the one most likely to survive archaeologically and resembled most closely the residues we observed on Mary Washington’s wares. Both hide glues seemingly disappeared from the vessels when inspected with the naked eye; however, placing our buried hide-glue examples under short-wave ultraviolet light revealed that trace amounts of the glue remained and fluoresced bright blue.

In order to determine what effects fluctuating temperature and humidity had on the glues, representative mended vessels were placed in a non-climate-controlled building on the property for six months, from late spring to early winter. Two glues appeared to have been altered by their exposure in the shed. A hide glue was observed to be yellowed and peeling from the surface of the cup, although the vessel itself stayed intact. A saucer mended with cheese glue appeared to be unaltered, although it fell apart shortly after being brought inside the archaeology lab, ultimately succumbing to the infamous Virginia heat and humidity. To test the strength of all of the glues, jars of identical volume were filled with water and placed on suspended mended flatwares. All passed this test, demonstrating that every glue type re-created produced a suitably strong adhesive, as claimed. Ultimately, however, the water test proved that none of the glues could mend a vessel to the point that it was completely functional. Hollow wares repaired with each of the experimental glues were filled with cool water to test the mends. Of the vessels mended with the two versions of hide glue, only one did not leak when it was filled with cold water, although it did fail the subsequent hot water test. The pine-resin glue resisted cold water well but became pliable in hot water, significantly weakening the mends. With its black appearance and brittle texture, the resin glue makes an unlikely candidate for mending refined wares such as those used in Mary Washington’s household.

Our experiments in adhesives indicate that the cheese and hide glues were the most effective in terms of ease of use and efficacy in joining fragments, and produced the most inconspicuous mends, although the resulting vessels did not hold water. The cheese glue, while the lightest in appearance and very good for mending white-bodied wares, was significantly weakened by moisture.

In general, our experimental attempts at understanding home ceramics mending yielded significant and promising results. Manufacturing adhesives for home use, while common, was a difficult, malodorous, and time-consuming task potentially exposing the mender to hazardous substances and, for these reasons, likely would have been accomplished by one of Mary Washington’s enslaved people. Our reproduction and use of period adhesives revealed that the glued ceramics were not functional and as such would not have been utilized post-mending for practical purposes by the family or any other plantation residents. This is further supported by the lack of even microscopic use wear on the ample glue residue adhering to the interior of the creamware punch bowl (see fig. 1). Although cast off or damaged ceramics are thought to have been passed down to servants (and, in this case, the enslaved), the location of the mended items exclusively within and around the house cellar indicates that they remained in the possession of the Washingtons. Furthermore, no repaired ceramics have been recovered from the vicinity of slave dwellings or activity areas. Glued vessels were likely employed to decorate the mantel or fill out a china closet or bowfat, a possibility also suggested by Angelika Kuettner in this volume.[19]

Residue Analysis

Chemical analysis of the archaeologically recovered eighteenth-century glue residues by Ruth Ann Armitage and Daniel Fraser have shed further light on the composition of the glues used to mend Mary Washington’s dishes. The samples were analyzed utilizing Direct Analysis in Real Time (DART) mass spectrometry and Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy. DART mass spectrometry is fast, requires only a small sample, and gives a molecular fingerprint of the material with little or no sample preparation. The mass spectrometer allows for determination of the composition of the samples and their comparison with other samples and materials. FTIR is a nondestructive method that has potential to inform us about the mineral composition of the residues, as well as any organic material that remains. As previously mentioned, replicated glues and raw ingredients were tested to provide a control for the glues sampled from Mary Washington’s ceramics. The mass spectrometer could clearly differentiate between the glues and raw materials.

Preliminary results from both tests show that all of the archaeological glue residues contained high concentrations of calcium carbonate with the exception of the glue from the porcelain fragment, which was contaminated with indeterminate inorganic substances. Lime was a major ingredient in most of the glue recipes we researched and replicated, likely because it provided a stabilizing aplastic much like temper in clay used for ceramics. The FTIR analysis of historic glues indicated that there was little to no remaining organic material relative to the mineral content. The replicated cheese glues that were buried for six months showed a similar decomposition of the organic material. Before burial, the cheese glues showed signatures characteristic of fats from cheese as well as calcium carbonate. After burial, all of the organic signals were lost, with only the calcium carbonate remaining.

More sensitive analytical methods might be able to detect traces of remaining organic compounds that are characteristic of the other ingredients in the historic glues. Previous work by Armitage and Fraser has shown detectable, statistically significant quantities of hydroxyproline in historic glues. This amino acid is present in large quantities in the protein collagen and might be a marker for either hide- or bone-derived glue. Additionally, neither DART-MS nor FTIR indicated the presence of resin compounds. While it is possible that resin compounds had completely decomposed during burial, it is equally possible that no resins were present in the original glues at all. Moreover, there was variation between archaeological glues, indicating several types of glues were present and, therefore, multiple mending episodes. This would seem to indicate a pattern of behavior in the Washington household rather than a onetime activity.

Conclusion

Our goal going into this study was to better understand the seemingly idiosyncratic attitude of Mary Washington toward mending ceramics. Through documentary research and experimental archaeology, we determined that ceramic repair at home was commonplace until the early twentieth century. Mary Washington’s decision to repair broken pieces may suggest a frugal woman who valued her possessions. It is telling that she chose to repair them at home, forgoing a professional mender. Through our experiences replicating eighteenth-century glue recipes available to her, and mending dozens of pots with the glues experimentally, it is clear to us that the vessels she had repaired at home would not have been functional. Given this, it is even possible that she had a sentimental attachment to one or more of these vessels, which resulted in her decision to salvage them. The punch bowl, as stated, did exhibit an extensive amount of use wear on the interior and may have been a favorite item of hers. Or perhaps these pots were valuable enough as showpieces that the demonstration of their ownership took precedence over utility.

In order to fully understand ceramics, we must have knowledge not just of ware and form types and dates of manufacture but also of how the pieces were utilized and the relationships people formed with them. Future research at Ferry Farm will be aimed at revealing more about the adhesives employed by eighteenth-century households. The hope is to gain more insight not only into the life of the Washingtons but also into how ceramics were used historically, their changing functions throughout their use-life, and how their utility could be both functional and communicative.

Patrick W. Edwards, “Why Not Period Glue?,” Journal of the Society of American Period Furniture Makers (November 2001): 2–3; John S. Mills and Raymond White, The Organic Chemistry of Museum Objects, 2nd ed. (London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2011).

Augustine Washington’s will can be viewed online at www.kenmore.org/genealogy/washington/augustine_will.html (accessed May 5, 2016).

David Muraca, Paul Nasca, and Philip Levy, Report on the Excavation of the Washington Farm: The 2004–2005 Field Seasons (Fredericksburg, Va.: George Washington Foundation, 2011), p. 14.

David Muraca, Paul Nasca, and Philip Levy, Report on the Excavation of the Washington Farm: The 2006–2007 Field Seasons (Fredericksburg, Va.: George Washington Foundation, 2010), p. 23.

Donald C. Towner, English Cream-Coloured Earthenware (London: Faber and Faber, 1957), p. 14.

Susan Gray Detweiler, George Washington’s Chinaware (New York: Harry N, Abrams, 1982), p. 209.

Personal communication with Kimberley Overman, February 3, 2016. Overman is the owner of the complete, repaired creamware punch bowl (H. 3", D. 6 1/4") that is enameled in black, red, green, and yellow paint with flower, cherries, and bud motifs. This non-archaeological whole example from the period represents exceedingly similar characteristics of the excavated bowl sherds from Washington’s Ferry Farm in size, design, and color choice.

Towner, English Cream-Coloured Earthenware, p. 14.

Angelika R. Kuettner, “Simply Riveting: Broken and Mended Ceramics,” in this volume.

Eric Boeda, Jacques Connan, Daniel Dessort, Sultan Muhesen, Norbert Mercier, Helene Valladas, and Nadine Tisnerat, “Bitumen as a Hafting Material on Middle Palaeolithic Artefacts,” Nature (1996): 380, 336–38; Marin Cârciumaru, Rodica-Mariana Ion, Elena-Cristina Nitu, and Radu Stefanescu, “New Evidence of Adhesive as Hafting Material on Middle and Upper Palaeolithic Artefacts from Gura Cheii-Râsnov Cave (Romania),” Journal of Archaeological Science 39, no. 7 (2012): 1942–50; Paul Peter Anthony Mazza, Fabio Martini, Benedetto Sala, Maurizio Magi, Maria Perla Colombini, Giana Giachi, Francesco Landucci, Cristina Lemorini, Francesca Modugno, and Erika Ribechini, “A New Palaeolithic Discovery: Tar-hafted Stone Tools in a European Mid-Pleistocene Bone-bearing Bed,” Journal of Archaeological Science 33 (2006): 1310–18.

S. Charters, R. P. Evershed, L. J. Goad, C. Heron, and P. Blinkhorn, “Identification of an Adhesive Used to Repair a Roman Jar,” Archaeometry 35, no. 1 (February 1993): 91–101; Rosamund Cleal, “The Occurrence of Drilled Holes in Later Neolithic Pottery,” Oxford Journal of Archaeology 7, no. 2 (July 1988): 139–45; Renske Dooijes and O. P. Nieuwenhuyse, “Ancient Repairs: Techniques and Social Meaning,” in Konservieren oder restaurieren: Die Restaurierung griechischer Vasen von der Antike bis Heute, 3rd suppl. to the CVA Germany (Munich: Beck Publishers, 2007), pp. 15–20; R. Michael Stewart, Ceramics and Delaware Valley Prehistory: Insights from the Abbott Farm, ed. Charles A. Bello ([South Orange]: Archaeological Society of New Jersey, 1998).

George L. Miller and Emily Brown, “A Harry A. Eberhardt–Repaired Chinese Porcelain Saucer,” in this volume; Maria Warwell, advertisement for mending china published in South-Carolina Gazette; and Country Journal, July 21, 1767.

George Weedon, Ledger of George Weedon, Fredericksburg City Archives, folio 13, 1773.

Arnold James Cooley, Book of Useful Knowledge: A Cyclopaedia of Six Thousand Practical Receipts and Collateral Information in the Arts, Manufactures, and Trades, including Medicine, Pharmacy, and Domestic Economy, Designed as a Compendious Book of Reference for the Manufacturer, Tradesman, Amateur, and Heads of Families (New York: D. Appleton and Co., 1851), p. 172.

Anonymous recipe, The Scots Magazine, vol. 27 (Edinburgh: Printed by W. Sands, A. Murray, and J. Cochran, 1765), p. 228.

Samuel Pepys, The Diary of Samuel Pepys—Complete, ed. Richard Griffin Braybrooke, Henry B. Wheatley (EBook-No. 4200, public domain in U.S.A., October 31, 2004), October 4, 1661.

John Nourse and Robert Dossie, The Handmaid to the Arts..., 2 vols., 2nd ed. (London: Printed for J. Nourse, Bookseller in ordinary to His Majesty, 1764).

Thomas Spencer Baynes, ed., The Encyclopædia Britannica: A Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, and General Literature, 9th ed. (New York: Henry G. Allen and Co., 1888).

Kuettner, “Simply Riveting: Broken and Mended Ceramics.”