Saucer, China, ca. 1790–1820. Porcelain. D. 5 3/4". (George L. Miller collection; photo, Robert Hunter.) The break can be seen in the lower right section of the plate.

The label on the back of the Chinese porcelain saucer illustrated in fig. 1.

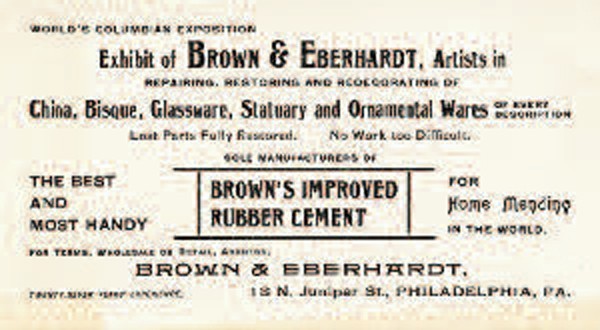

Trade card, Brown & Eberhardt, Philadelphia, ca. 1892. (Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera, Collection 46, Winterthur Library.)

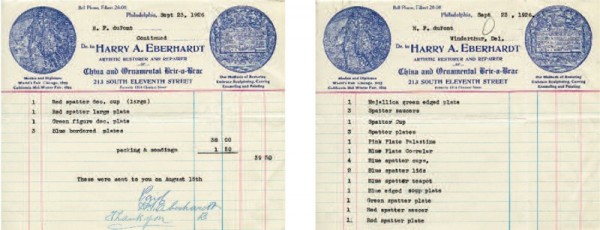

Invoices, Harry A. Eberhardt, Philadelphia, September 23, 1926. (Winterthur Archives, Winterthur Library.)

Workers repair broken china dishes with copper rivets, Samarkand, Uzbekistan, twentieth century. (photo, Maynard Owen Williams; National Geographic Stock: Vintage Collection / Granger, NYC—All rights reserved.)

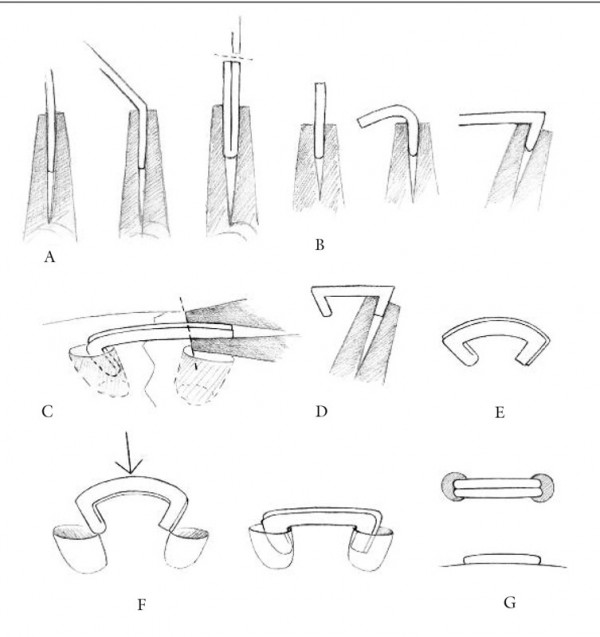

Illustration of riveting process described by William R. Eberhardt and based on images found in Claudia S. M. Parsons and Frederick H. Curl, China Mending and Restoration (London: Faber and Faber, 1963), pp. 49, 52, 55. The illustration shows how: (A) the wire is bent double; (B) the first rivet leg is bent and hammered into position; (C) the second leg is measured; and (D) the second leg is formed. The remaining images show: (E) the completed rivet with a bowed shape; (F) the rivet in position at the holes; and (G) the final appearance of the rivet when viewed from the top and side.

Drill stock with solid metal flywheel. (Photo, William David Brown.)

Emily Brown holding the wooden crossbar wound in position around spindle to begin drilling movement. (Photo, William David Brown.)

Detail showing the rivets in the saucer illustrated in fig. 1. (Photo, Robert Hunter.)

Several years ago George Miller purchased a group of painted Staffordshire saucers at the flea market in Columbus, New Jersey. The lot included a “Canton”-pattern Chinese porcelain saucer, which had a break that had been repaired with three rivets (fig. 1). The back of the saucer has a printed paper label (fig. 2) that reads “HARRY A. EBERHARDT / Art & China Repairing / 213 S. 11th St., Phila. Pa.” Below the printed label is a faded handwritten note, which, when viewed under long-wave ultraviolet light, is seen to read “17228 Cauffman / 3 Riv.” The number “17228” is the Eberhardt record of the repair; “3 Riv” is probably shorthand instructions for three rivets to be placed along the break for the repair. The name “Cauffman” most likely refers to Joseph Cauffman, the proprietor of the Benjamin Franklin Antique Shop in Philadelphia from the 1920s.[1]

After acquiring the saucer George ran across an advertisement for Harry A. Eberhardt & Son in the July 1930 issue of Antiques.[2] The advertisement pictured several broken ceramic vessels with the caption “MISSING PARTS of Antiques china and pottery replaced; this work does not show. / Expert Repairing of Art Goods / Established 1888.” The advertisement had the same address as the one that appears on the paper label. Given that the 1930 advertisement added “& Son,” the repair of the saucer most likely was done before that date. The company was in business until December 2015, trading under the name H. A. Eberhardt & Son Inc. at 2010 Walnut Street in Philadelphia. Its website (eberhardts.com) bears the claim “The Antiques Shop and Restoration Studio came from Europe to America on, or before earliest records of 1865. The firm began trading as Eberhardt’s in 1888, when Harry A., grandfather of William R. Eberhardt, the current owner, became a partner.”

While researching the Eberhardt company, George Miller was joined by Emily Brown, a Graduate Fellow, Class of 2015, in the Winterthur/University of Delaware Program in Art Conservation. Prior to entering the Winterthur conservation program Emily had worked for the Eberhardt company for fourteen years, performing restoration work on ceramics, glass, and other types of decorative objects.

Rivet Repairs, Some History of the Practice

Father Martinus Martini, a Jesuit missionary in China, published one of the earliest descriptions of riveting ceramics in his 1655 publication, Novus Atlas Sinensis.[3] When riveting began to be practiced in Europe is not clear. One of the earliest advertisements for riveting ceramics in the American colonies occurred in the Boston Gazette on October 20, 1755. The advertiser offers to repair broken china “by riveting with Silver or Brass Rivets.”[4] An advertisement in the Leeds Intelligencer on May 12, 1761, placed by Robinson and Rhodes for enameling of ceramics mentions mending porcelain by firing broken pieces with a glass or glaze composition between the breaks as an alternative to repairing by riveting the china.[5] By the 1760s there were china repairers advertising in New York, Philadelphia, and Charleston, South Carolina. David Hall, a Philadelphia jeweler, advertised in the Philadelphia Gazette of February 20, 1766, that, in addition to making all sorts of gold and silver work, he “drilled and clasped” china bowls and added wooden handles to teapots.[6] Nathaniel Lane advertised in The New-York Journal or General Advertiser on July 9, 1767, that “Broken China and Glass, Mended and riveted in the neatest manner and on reasonable Terms. . . . The Price of Rivets, if he finds the Silver is 2s [shillings] each if Silver is found 1s each Rivet, if Brass, is 1s if white metal 6d [pence].”[7] Joseph Dix, a Philadelphia watchmaker, advertised in the Pennsylvania Journal on December 14, 1769, “China Ware Rivetted. Very secure and in a neat manner, different to what is commonly practiced in riveting. . . .”[8]

Thus it is clear that, at least by the 1750s but probably earlier, ceramic repair was being done by riveting in the American colonies. That tradition continued into the 1950s, as indicated by the correspondence between Henry Francis du Pont and Harry A. Eberhardt.

Researching the Eberhardt company at Winterthur proved productive. There is extensive correspondence between du Pont and Eberhardt concerning restoration of ceramics and glass for Mr. du Pont’s collection. In addition, the Downs Collection has a trade card for Brown and Eberhardt from the Columbian Exhibition that was held in Chicago in 1892 and 1893 (fig. 3).[9] The trade card suggests that Brown and Eberhardt began in business in about 1865. Later printed invoice forms for Harry Eberhardt illustrate a medal that was awarded to various entrants in the Columbian Exposition (fig. 4).[10] The medal had a blank space for the engraving of the awardee’s name. The illustrated medal has “H. A. EBERHARDT” engraved in that space.[11] A Google search of “Brown’s Improved Rubber Cement” produced a reference to a patent for that product being taken out by John J. Brown on October 31, 1876.[12]

We are fortunate to have the extensive correspondence between Henry Francis du Pont and Harry A. Eberhardt that has been preserved as part of the Winterthur Archives in the Winterthur Library. This correspondence has carbon copies of letters sent by Mr. du Pont to Mr. Eberhardt and the response letters written on printed letterhead along with invoices for work completed. The earliest correspondence is a letter from du Pont to Eberhardt Brothers dated June 2, 1924, mentioning a “small Lowestoft stopper” to a tea caddy that had been badly restored. A great deal of the ceramics sent for restoration was referred to as Lowestoft, which was the common name for Chinese porcelain during that period.[13] The last correspondence in the Winterthur Archives is an invoice from William A. Eberhardt & Son to du Pont that is dated April 16, 1968. The bulk of their correspondence occurred between 1925 and 1940, a period during which du Pont was very active in collecting ceramics. While some of the correspondence concerns ceramics sold to him, most of the letters and invoices relate to orders for ceramics to be repaired and cleaned. In many cases, the detail is vague and does not mention what type of repair was being commissioned. In other cases the interchange of letters provides excellent details of what is to be done and the cost of the restoration.

Comments on Ceramics to Be Riveted

A letter written to du Pont on Harry A. Eberhardt letterhead dated February 13, 1926, reads as follows:

Dear Sir

Your chauffer brought to my place for repairs

7 Lowestoff [sic] plates all have been broken & painted over

2" Tureens no lids both have breaks painted over

3" After dinner coffee cups handles have been made of composition & painted over

1" Tea caddy no lid otherwise perfect

2 spatter cups & saucers

I am writing to find out whether you want these pieces riveted together for table use [“yes” handwritten in pencil on letter] if so we will remove the paint take them apart clean the edges & join them & rivet on the bottom side the breaks will show slightly but there will not be any paint to scale off. If you Just want them for cabinet use we will clean them thoroughly & rejoin them by cementing only. awaiting further information & instruction on the above work.

Respectfully,

HAEberhardt

Du Pont responded in a letter dated February 16, 1926, saying that he wanted the vessels riveted together for table use. Parsons and Curl’s 1963 book China Mending and Restoration states that riveting should be limited to tableware because it comes in contact with hot water, detergents, and steam. This type of repair did not use any adhesives, and vessels repaired with rivets would be watertight.[14] The cost for repairing du Pont’s seventeen vessels was $49.30. Unfortunately, the number of rivets involved is not listed. However, there is a cost on the riveting of cups in a line that reads: “3 Lowestoff [sic] cups only 1 riveted $1.20,” which gives an indication of the price of riveting. Another invoice from Eberhardt to du Pont dated July 17, 1931, reads: “15 pieces of Lowestoft 159 rivets & restoring $115.00.” That comes to $0.72 per rivet, not including the restoration of the wares or an average of $7.67 per vessel that was restored.

A handwritten note sent to du Pont on a postcard dated March 7, 1933, reads: “Now is the time to have those pieces of china repaired as we have reduced our prices to just meet the cost Riveting of china & glass [illegible] 35 a rivet & other work accordingly.” It was signed “Eberhardt Bros.”

The large volume of restoration work done for du Pont is recorded in the Eberhardt–du Pont correspondence from 1925 through the 1930s. A letter on Harry A. Eberhardt & Son letterhead and dated September 16, 1931, gives an idea of the quantities that might be sent for restoration: “The lot of china we were repairing for you has been completed, and I think it would be advisable to send the station car as it consists of 2 barrels & 3 cartons.” Clearly, du Pont did not limit his collecting to perfect objects. The last invoice that mentions rivet repairs is dated March 13, 1950, and the last invoice from Harry Eberhardt & Son to H. F. du Pont in this collection is dated April 16, 1968.

The Winterthur Museum Objects catalog lists at least five vessels that still have Eberhardt repair labels. Only one of them has rivet repairs. It is a blue shell-edged basin by Andrew Stevenson that has ten rivets.[15] Unfortunately, the Winterthur catalog records do not indicate when Eberhardt repaired the pieces.

The End Use of Riveting for Ceramic Repair

According to William R. Eberhardt, the son of Harry A. Eberhardt Jr. and the grandson of the founder of H. A. Eberhardt & Son Inc., repairing ceramics and glass with rivets ended about sixty years ago.[16] Eberhardt said that the repair business had declined to a great extent. They used to have four people employed in restoring ceramics and other objects and in 2012 had only one. Eberhardt grew up in the business and was trained in the restoration of ceramics and artworks by his family. In his younger years he had done rivet repairing of ceramics. One of Eberhardt’s employees who retired after forty years had done rivet repairs of ceramics, a task now done with better-quality cements such as epoxy. In China Mending and Restoration, Parsons and Curl state that “recent scientific developments in adhesives have led many people to believe that riveting is now obsolete.”[17] The transition to epoxy for ceramic repair is echoed in Thomas Pond’s book Mending and Restoring China that was published in 1970. Pond entered the restoration business in the 1960s, and he states his feeling about rivets in the following passage.

In 1963 a 5 guinea book was published on china mending [clearly the Parsons and Curl book], and of its 420 pages over half were devoted to riveting and doweling. I have found riveting difficult and unsatisfactory and have always avoided it. In fact my greatest pleasure is to extract all rivets and re-mend and restore with modern glues, which were not at the disposal of restorers until ten years ago.[18]

Although the riveting of ceramics seems to have come to an end in America and probably England, it is still practiced in other countries. A recent color photograph by Maynard Owen Williams for National Geographic shows two men with bow drills repairing vessels in Uzbekistan with a collection of teapots and other vessels in front of them in an outdoor market (fig. 5). The photograph is labeled “Workers repairing broken china dishes with copper rivets.”[19]

The Process of Riveting Ceramics

Fortunately, the process of riveting ceramics has been very well described in China Mending and Restoration.[20] A rivet looks like a staple with a long, center section and two short legs, one at each end. The legs are at a slight angle toward the break line so that the staple exerts pressure on the fragments to be joined together. Rivets were commonly made from half-round brass or German silver wire that ranged in size from 18 to 12 gauge. In this scale, the 18 gauge is the smallest size used and was commonly used to repair cups. Thicker gauge wire was used for larger vessels, such as platters.[21]

The process of riveting pottery or porcelain together involved cleaning the broken surfaces, putting the vessel together with tape, and marking places where holes would be drilled for the placement of the rivet—on the back of the vessel, especially if it was to be used after repair rather that just being on display. Rivets were placed a couple of inches apart, at right angles to the break line so that the clamping force would not distort the movement along the break. Once the locations were marked, small holes were drilled with a diamond-tipped tool that was rotated by a bow or pump drill.[22] The drilled holes were at a 15-degree angle, facing in toward the fracture, and they were drilled only partway into the body.

Once the holes were drilled, the half-round brass or German silver wire was cut off and one end bent at the 15-degree angle, which was placed into the hole to make sure it was a good fit. Then the half-round wire was laid across the break with one leg in the drilled hole, which established the position to bend the second leg of the rivet, which was also at a 15-degree angle to the break. Once the rivet was made and one end placed, the other end was pushed into place by a pair of needle-nose pliers. If the rivet was well made, the pressure it exerted on the fragments formed a solid bond. Once all of the rivets were placed, any open areas around the drill holes were filled with plaster of Paris or other material.[23]

William R. Eberhardt said that he was trained in riveting as a young man. His description of the process is parallel to that described above with a couple of differences (fig. 6): They used German silver wire because he said that it “retained its springiness.” The wire was bent double (a) and the doubled end was bent to form the first leg to be fitted into the hole (b and c). A slight bow was given to the rivet (e) so that when ready to be placed, the second leg could be maneuvered into place by pressing on the bowed section of rivet toward the vessel being repaired (f). This would extend the second leg of the rivet into the hole drilled for it. From this description, it appears that different gauges of wire were used.[24]

A drill used for riveting by Eberhardt & Son was recently rediscovered by Emily Brown after a visit to their offices (figs. 7, 8). She was given a sample of what is believed to be the wire used to make rivets, as described above. It is a round wire of a small gauge, which most certainly could have been used to make a rivet as described by Eberhardt.

The middle rivet on the saucer illustrated in figure 1 (fig. 9) was analyzed at the Scientific Research and Analysis Laboratory (SRAL) at Winterthur Museum using X-ray fluorescence (XRF) analysis.[25] XRF is a process whereby X-ray beams excite electrons in a material. These excited electrons emit X-rays of their own, which are characteristic of the atomic element present in a material. In this way scientists can determine the elemental composition of a work of art. XRF analysis on the saucer rivet detected the presence of copper, nickel, and zinc, positively identifying it as German silver.

From the correspondence between du Pont and Eberhardt it can be seen that there are different reasons for having ceramics repaired. One of the earliest reasons for such repair would be to restore vessels to usefulness. This is suggested by the eighteenth-century advertisements described above. In such cases the ceramic vessel might not be an antique. When one vessel of a set was broken, the repair might have been to maintain a complete set. The Canton-pattern porcelain saucer discussed here was not an item of great value, and one wonders if the repair was undertaken to maintain an intact set of teaware. The correspondence shows that riveting was not a very expensive process. Another factor in paying to have a vessel repaired might be because it has emotional value, in terms of who gave the vessel or from whom it was inherited. Antique vessels of value would make a natural candidate for repair. Clearly this was part of the motivation for repairing many of the vessels that du Pont sent to Eberhardt for repair.

From the correspondence between du Pont and Eberhardt, it does not seem possible to determine the ratio of repairs that were done with rivets versus cements or which objects were in for cleaning or covering over chipped areas. In addition, some of the invoices from Eberhardt were for ceramics sold to du Pont. Beyond that there is the question of what proportion of the business was for antique ceramics versus repairing household ceramics for continued usage once they had been restored. Clearly, the repairs, cleaning, and restorations done for Henry Francis du Pont are not typical of the range of materials repaired by H. A. Eberhardt & Son.

An insight into the repair business can be gotten from Emily Browns’s daily work log at Eberhardt’s, which sheds some light on the nature of the business. From August 4 to August 27, 2010, she worked a total of 100 hours, during which period she handled 101 objects for various types of treatment, ranging from cleaning up old mends, restoring vessels back together, touchup painting of patterns, and other activities. These objects belonged to 77 clients, and 59 were completed during that work period. Major portions of these items were ceramic, but there were also some glass and wood items, and one resin object was repaired. Many of the items were not antiques; figurines were the most common item being repaired. These appear to be modern collectible and/or art objects, which include 22 Llado figures out of the 33 figurines that were restored. This record of what was typically being restored helps bring a balance to the record of the restoration work done by Harry A. Eberhardt & Son for Henry Francis du Pont.

While riveted ceramics can be found in antique shops and flea markets, they rarely bear the labels of who did the repairs. Thus, vessels with repair labels provide an insight into the vessel’s history and are to be treasured. Those labels will be valued even more in the future as the firm of Harry A. Eberhardt & Son, after being in business continually since 1888, closed its doors in 2015, leaving a legacy of repaired china dishes throughout the Philadelphia region.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful for the information and comments on our paper provided by William R. Eberhardt, third-generation owner of H. A. Eberhardt & Son Inc., who grew up in the family business and repaired ceramics with rivets when he was younger. His description of the process was most helpful. We extend our appreciation to Winterthur librarians Heather Clewell, Jeanne Solensky, and Laura Parrish for their assistance in locating Eberhardt materials and securing copies of them. I would also like to thank my wife, Amy C. Earls, for proofreading earlier versions of this paper.

Some letters to Henry Francis du Pont in the Winterthur Archives are from Joseph Cauffman, the proprietor of the Benjamin Franklin Antique Shop in Philadelphia. He might well be the person who had the saucer repaired. The letters date from March 1927 to July 1934.

Advertisement, Antiques 18, no. 1 (July 1930): 83.

Bevis Hillier, Pottery and Porcelain, 1700–1914: England, Europe, and North America (New York: Meredith Press, 1968), pp. 301–2.

George Francis Dow, The Arts & Crafts in New England, 1704–1775: Gleanings from Boston Newspapers Relating to Painting, Engraving, Silversmiths, Pewterers, Clockmakers, Furniture, Pottery, Old Houses, Costume, Trades and Occupations &c...(Topsfield, Mass.: Wayside Press, 1927), p. 88.

Donald C. Towner, The Leeds Pottery, 1st American ed. (New York: Taplinger Publishing Co., 1965), p. 164.

Alfred Cox Prime, comp., The Arts and Crafts in Philadelphia, Maryland, and South Carolina: Gleanings from Newspapers (Topsfield, Mass.: Walpole Society, 1929), p. 67.

Rita S. Gottesman, comp., The Arts and Crafts in New York, 1726–1776: Advertisements and News Items from the New York City Newspapers, Da Capo Press Series in Architecture and Decorative Art 35 (1938; reprint, New York: Da Capo Press, 1970), pp. 86–87.

Prime, comp., Arts and Crafts, p. 237.

Brown and Eberhardt trade card, Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera, collection 46, 68 x 155.92, Winterthur Library.

Brown and Eberhardt trade card, Winterthur Archives, HF 153, Winterthur Library.

Printed invoice from Harry A. Eberhardt to H. F. du Pont, dated June 7, 1927, in the collection of invoices to H. F. du Pont in the Winterthur Archives, Winterthur Library

Patent No. 859: Annual Report of the Commissioner of Patents for the Year 1876 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1877), p. 235 (Official Gazette, vol. 10, p. 705).

Lowestoft was an English porcelain factory. William Chaffers writing about this factory claimed that Chinese porcelains were being decorated there and that situation gave rise to collectors and antiques dealers talking about “Oriental Lowestoft.” His Marks & Monographs on European and Oriental Pottery and Porcelain, 15th ed. (London: William Reeves, 1965), states that the British section was edited by Geoffrey A. Godden. Under “Lowestoft” in volume 2, p. 211, it states: “Previous editions have closely followed William Chaffers’ original writings, in which he attributed a class of hard paste Chinese porcelain (decorated for the European market, with armorial bearings, etc.) to the Lowestoft factory. Former editors have added notes in an endeavor to correct Chaffers’s serious error but confusion still arises. The time has not arrived to rewrite the Lowestoft section and in so doing to mention the confusing hard paste myth has been deleted.” Chaffers’s claims were rejected by L[ouis] M[arc] Solon’s book A Brief History of Old English Porcelain and Its Manufactories, with an Artistic, Industrial, and Critical Appreciation of Their Productions (London: Bemrose & Sons, 1903), pp. 210–11. Because collectors and dealers nevertheless continued to use the term “Oriental Lowestoft” into the 1950s, mentions of Lowestoft in the Eberhardt–du Pont correspondence are most likely references to Chinese porcelain.

Claudia S. M. Parsons and Frederick H. Curl, China Mending and Restoration (London: Faber and Faber, 1963), pp. 27, 63.

Winterthur Museum Object Catalog no. 1969.0357, Eberhardt repair no. 10746.

William R. Eberhardt and George Miller, telephone conversation, August 14, 2012.

Parsons and Curl, China Mending, p. 20.

Thomas Pond, Mending and Restoring China (New York: Avenel Books, 1970), introduction.

Available online at www.corbisimages.com/Search#q=42-32917977&p=1 (accessed August 21, 2013).

Parsons and Curl, China Mending, n. 12. The authors dedicated 37 pages (28–64) to the process, including excellent line drawings that take the reader through drilling the holes, creating the rivet, and the process of pushing it into the prepared holes.

Ibid., p. 28.

For a long description of setting an industrial diamond chip into the end of a iron shaft such as a nail and finishing it into a bit for drilling ceramics, see ibid., pp. 144–51.

This description was taken from ibid., pp. 58–64.

William R. Eberhardt and George Miller, telephone conversation, August 14, 2012.

Analysis was performed using a Bruker ARTAX XRF spectrometer equipped with a rhodium tube at 500 A current, 40 kV voltage, and 100s live time, and beam spot size of 70–100 m. Spectra were collected and analyzed using Bruker ARTAX computer software (version 7.2.5.0).