Jar, attributed to Morgan pottery, Cheesequake, New Jersey, 1775–1784. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 12 1/4". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

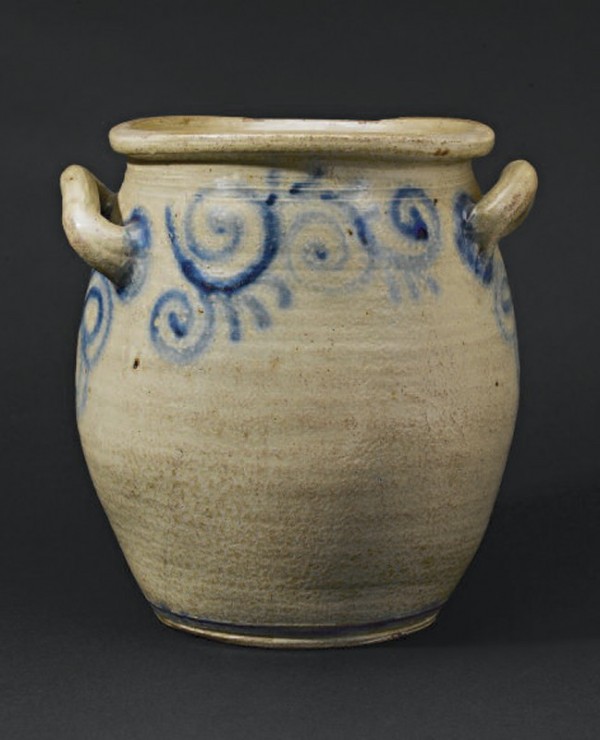

Jar, Kemple pottery, Ringoes, Hunterdon County, New Jersey, ca. 1746–1790s. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 11". (Courtesy, Monmouth County Historical Association, Gift of Mrs. J. Amory Haskell; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Jar fragment, Morgan pottery, Cheesequake, New Jersey, 1775–1784. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Courtesy, Robert J. Sim Collection, MCHA; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This fragment displays a typical example of Morgan’s cobalt-blue watch-spring motif.

Jar fragment, Kemple pottery site, Hunterdon County, New Jersey, ca. 1746–1790s. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Courtesy, Robert J. Sim Collection, MCHA; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

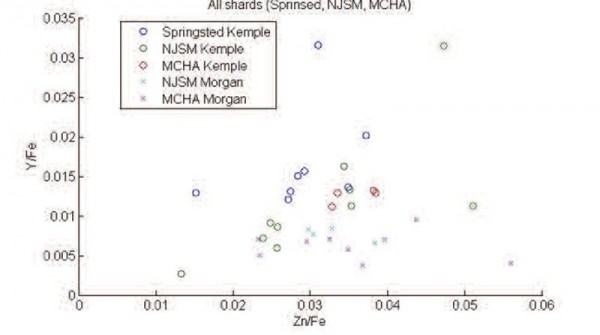

Bivariate elemental plot comparing Zn/Fe and Y/Fe content for the Morgan and Kemple sherds.

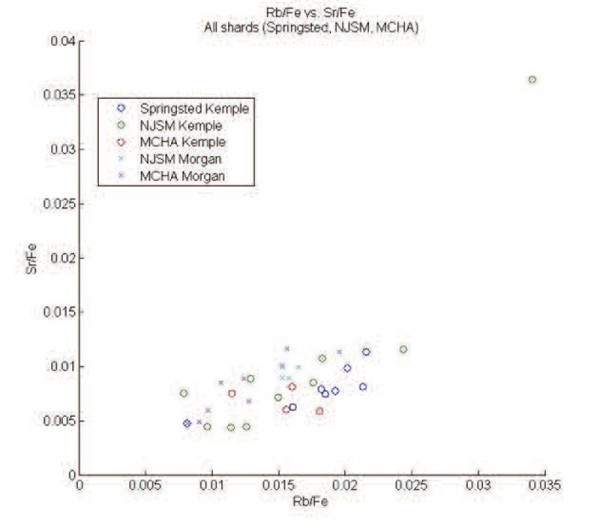

Bivariate elemental plot comparing Sr/Fe and Rb/Fe content for the Morgan and Kemple sherds.

This study is a scientific comparison of stoneware fragments found at the New Jersey archaeological sites of the pottery of Captain James Morgan of Cheesequake (ca. 1775–1784) and the Kemple family pottery in Ringoes (1746–1778) (figs. 1, 2). The study was undertaken to help resolve unanswered questions discussed in “The Eighteenth Century New Jersey Stoneware of Captain James Morgan and the Kemple Family,” published in this journal in 2008.[1] Those questions focused in part on the source of the clay used by the Kemple family pottery. A scientific examination of the stoneware fragments would, it was hoped, provide an elemental signature for the clay that was used at these potteries, allowing identification of intact vessels currently attributed to these potteries but without documented provenance. Important to the history of New Jersey manufacturing, this research was the first attempt to identify the materials used to make some of the earliest stoneware in America.

The importance of this investigation was based in part on the findings of archaeologist Meta Janowitz’s study of sherds from the African Burial Ground that were considered to be from 1730/40–1760, when the area was a dump site for the potteries of William Crolius and John Remmey.[2] Some of these sherds exhibited the watch-spring design typical of James Morgan, others showed the cogged watch spring used by the Kemple family pottery. Janowitz’s findings raised doubts about attributions of Morgan and Kemple vessels that were based solely on their designs. For this reason, an examination of differences in the elemental composition of the clay among all the potteries was undertaken to help determine where the pots were made.

There is no known historical documentation about the clays that the Crolius and Remmey families used circa 1730–1760 to make their stoneware. William C. Ketchum Jr. states that, according to Adriaen van der Donck in his Description of New Netherland, one finds that “New York has hills of fuller’s earth and some ne clay such as white, yellow, red and black suitable for pots, dishes, plates tobacco pipes and like wares.”[3] Ketchum notes that this is most likely where John William Crolius first worked and possibly he could have been using that clay.[4] It is possible, however, that clay was purchased from the clay bank located in the vicinity of Cheesequake and owned by the Morgan family since 1710. Captain James Morgan inherited the banks in 1764 and started to make stoneware in the 1770s.[5] While there is no evidence of any sale of clay during that time, the quality of clay from the Morgan bank was widely known and in the 1790s was shipped as far away as New England by Captain Morgan’s son (also James), General Morgan.[6]

Unlike the clay banks owned by the Morgan family, the clay source for the Kemple family pottery has not been documented and is the focus of this scientific study. Three possible clay sources for this pottery have been considered. First, the Kemples might have purchased their clay from the Morgan clay banks located about thirty miles away from their operation. Second, they might have been mixing higher quality clay from the Morgan banks with local clay of a different/lesser quality.[7] Third, perhaps there was another, undocumented source of stoneware clay, although this is considered improbable based on the geology of the surrounding area. Any differences in the clays would show up in trace element analysis of stoneware from each pottery. The presence or absence of trace elements in the composition of the red clay has been commonly employed as an indicator of differences in the clay source.

The primary method of analysis employed was energy dispersive X-ray fluorescence (XRF), a standard method of nondestructive elemental analysis for cultural materials. XRF has been used to examine the trace elements in archaeological pottery to determine clay provenience.[8] Elemental analysis is used routinely in art conservation to identify materials such as overpaint on paintings and furniture, and to identify anomalous materials that could call into question the authenticity of an object. In the case of ceramic materials, elemental analysis using X-ray–based techniques such as XRF are among the most useful. That XRF is nondestructive gives it an advantage over other elemental analysis methods.

Summary of Analysis

The unglazed edges of thirty-five stoneware fragments—thirteen from the Morgan pottery (fig. 3) and twenty-two from the Kemple pottery (fig. 4)—were examined at the Winterthur Museum Scientific Research and Analysis Laboratory using an energy dispersive X-ray spectrometer (Roentec/Bruker ArtTAX spectrometer with the molybdenum X-ray tube measurement head; measurement spot size is ~75 m). The fragments came from the collections of the New Jersey State Museum (NJSM), the Monmouth County Historical Association (MCHA), and Brenda Springsted, a private collector.

Each specimen was analyzed three times on an unglazed edge at three different spots using 300s exposures at 50 kV (600 A). An average of the three scans from each fragment was performed to account for the variations in signals from the clay bodies due to variations in the physical and chemical structure of the clay body and the variations in the smoothness of the test surface. Variations in the chemical signature within a single sherd are likely due to the heterogeneous nature of the red clay body as compared to the spot size of the X-ray beam.

The area under selected peaks in the spectra was measured, concentrating on the following elements: calcium (Ca), chromium (Cr), copper (Cu), iron (Fe), manganese (Mn), nickel (Ni), potassium (K), rubidium (Rb), strontium (Sr), titanium (Ti), yttrium (Y), zinc (Zn), and zirconium (Zr). Data analysis focused on Cu, Fe, Rb, Sr, Y, Zn, and Zr concentrations. The measured values for each peak were averaged for each sherd and were plotted as bivariate component elemental plots. Each averaged measurement was divided by the corresponding averaged measurement for Fe for each sherd in order to minimize the effect of intensity variations in the average signals.

Discussion

Examination of the plot comparing the Zn/Fe and Y/Fe contents of the Morgan and Kemple sherds (fig. 5) shows that there might be a weak correlation for yttrium, suggesting that the clay used at the Kemple pottery contains slightly more yttrium than that of the Morgan pottery. The plot for Rb/Fe versus Sr/Fe (fig. 6), however, does not show significant variation in the Rb/Sr ratio for each pottery.

If both potteries were using the same clay source, one would expect little difference in the chemical content of the clay bodies and no correlation of elemental composition to pottery for any of the selected elements. It is possible that the yttrium concentration difference can be explained if the Kemple pottery mixed local clay with clay from the Morgan bank, as has been previously suggested.

Further examination of the plot for yttrium shows greater scatter for the Kemple stoneware, which is consistent with the clay-mixing theory. Possibly the Kemple pottery had another unknown clay source, with similar but not identical composition. Given the geology of the area, however, this last possibility may be the least likely.

A 1977 report written by James P. Owens, N. F. Sohl, and J. P. Minard indicates that the ratios of the clay minerals vary from one part of the Morgan clay bank to another.[9] While XRF is generally not able to show these differences, the slight variation in the yttrium content of the clays from the two potteries indicating differences in the ceramic bodies could be explained by variations in the Morgan clay bank itself. However, closer examination of figures 5 and 6 show that there is generally more scatter associated with the Kemple data. If the variations in the Morgan clay bank were significant, we would likely also see similar scatter associated with the Morgan stoneware results. In fact, there is actually less scatter associated with the Morgan samples.

Ultimately, the results of this XRF study show that subtle differences in the clay bodies from these two potteries are observable by examination of their trace element contents. XRF is an ideal nondestructive tool for identifying trace elements in clays.

Future research will concentrate on sampling clays from the historic Morgan clay bank, and examination of fragments using sampling techniques that are able to quantify bulk trace element content (rather than the surface trace element content that is observed with XRF). Such techniques may include ICP-MS (inductively coupled plasma analysis with mass spectrometry), XRD (X-ray diffraction), and petrographic analysis.

Other areas for examination include analysis of the cobalt blue decoration on the Morgan and Kemple sherds and their attributed vessels. Inclusion of the Crolius/Remmey sherds from the African Burial Ground site will also help to establish differences between unmarked eighteenth-century New York and New Jersey stoneware. Further analysis of Morgan and Kemple sherds will reveal whether the yttrium effect is statistically significant. Originally, this research was to have included fragments from the Crolius/

Remmey potteries that were excavated at the African Burial Ground site. Unfortunately, the Government Services Administration, which houses these collections, changed its lending policies and the fragments became unavailable for study. The date for their release and transfer is not known.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are grateful for the New Jersey Historical Commission grant (2007–8) that provided the funding to perform the initial research for this study, as well as to the New Jersey State Museum in Trenton, the Monmouth County Historical Association in Freehold, New Jersey, and archaeologist Brenda Springsted for lending us their examples.

Arthur F. Goldberg, Peter Warwick, and Leslie Warwick, “The Eighteenth-Century New Jersey Stoneware Potteries of Captain James Morgan and the Kemple Family,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2008), pp. 3–40.

Meta F. Janowitz, “New York City Stonewares from the African Burial Ground,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2008), pp. 41–66.

William C. Ketchum Jr., Potters and Potteries of New York State, 1650–1900, 2nd ed. (Syracuse, N.Y.: Syracuse University Press, 1987), pp. 39–40, quoting Adriaen van der Donck, Esq., Description of New Netherland, first English edition published in 1841 (widely considered a bad translation), Collection of the New-York Historical Society.

Ketchum, Potters and Potteries of New York State, p. 40.

Goldberg, Warwick, and Warwick, “Eighteenth-Century New Jersey Stoneware Potteries of Captain James Morgan and the Kemple Family,” p. 32.

Lura Woodside Watkins, Early New England Potters and Their Wares (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1950), pp. 82–83.

Goldberg, Warwick, and Warwick, “Eighteenth-Century New Jersey Stoneware Potteries of Captain James Morgan and the Kemple Family,” p. 25.

E. H. Balffaji, “Application of Multivariate Sstatistical Methods to Classify Archeological Pottery from Tel-Alramad site, Syria, Based on X-ray Fluorescence Analysis,” X-ray Spectometry 35, no. 3 (2006): 190–94. F. P. Romano, G. Pappalardo, L. Pappalardo, S. Garraffo, R. Gigli, and A. Pautasso, “Quantitative Nondestructive Determination of Trace Elements in Archeological Pottery Using a Portable Beam Stability-Controlled XRF Spectrometer,” X-ray Spectometry 35, no. 1 (2006): 1–7.

. J. P. Owens, N. F. Sohl, and J. P. Minard, “A Field Guide to Cretaceous and Lower Tertiary Beds of the Raritan and Salisbury Embayments, New Jersey, Delaware and Maryland,” presented at the Annual AAPG/SEPM Convention, Washington, D.C., June 12–16, 1977. Excerpts of this report were provided by Peter Sugarman, New Jersey Geological Survey.