Puzzle jug, probably South Yorkshire, England, ca. 1798. Pearlware. H. 11". (Author’s collection; unless otherwise noted, all photos by Robert Hunter.) This undated pearlware puzzle jug was made for shipmaster John Bloome and includes polychrome-painted decoration depicting his ship Hopewell.

Detail of the ship stern on the puzzle jug illustrated in fig. 1. The image shows the ship’s name as “Hopewell” and below it “Wells” and what at first looked like an arrow-pierced heart but turned out to be “of”—i.e., Hopewell of Wells.

Puzzle jug, attributed to Ferrybridge Pottery, Yorkshire, England, 1849. Yellow ware. H. 7 1/2". Dated 1849 and inscribed with the initials MHS in blue slip. (Author’s collection.) The form is an example of declining elegance in puzzle jug production.

The ship Hopewell in a detail of the puzzle jug illustrated in fig. 1. The ship is under sail and flying the flag (red ensign) of the British Merchant Navy.

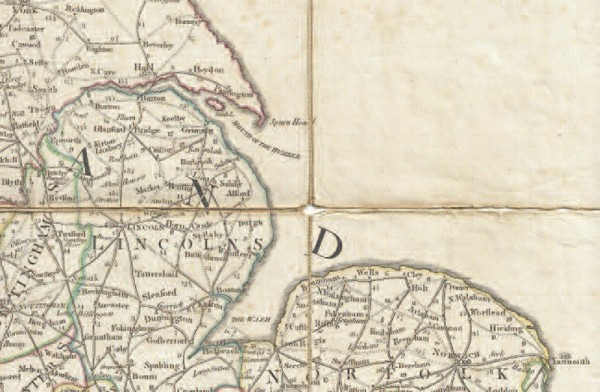

Detail of William Faden’s The Roads of Great Britain. Initneraire de la Grande Bretagne, 1790. (Courtesy, Geographicus Rare Antique Maps.) The map shows a portion of the east coast of England, with the ports of Wells and Hull indicated.

The Wells estuary at low tide. The Hopewell ran aground about three miles to the east. (Photo, Mike Page Aerial Photography, www.mike-page.co.uk.)

Photo of a transfer-printed creamware plate showing the encounter between the Baltic trader Crow Isle and John Paul Jones in 1779. Reproduced from Oxley Grabham, Yorkshire Potteries, Pots and Potters (1916; reprint, Wakefield: S. R. Publishers, 1971). The plate, now lost, is allegedly the product of a Hull potter.

Ceramic artist Michelle Erickson holds the Admiral Duncan commemorative pitcher discovered at the 2016 New York Ceramics Fair in the booth of London dealer Garry Atkins.

The Venerable pitcher and Hopewell jug in hand-painted pearlware, the former dated 1797 and a memorial to victory at the Battle of Camperdown. Both are believed to be the product of a single Leeds painter.

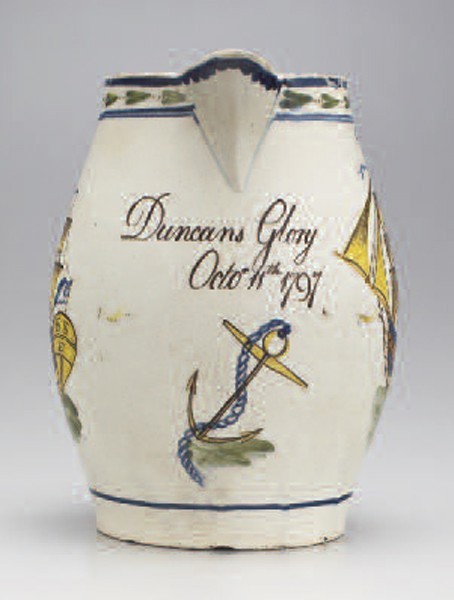

Pitcher, probably South Yorkshire, England, ca. 1797. Pearlware. H. 8 1/2". Inscribed on front: “Duncans Glory / Octo 11th 1797” over a blue-chained anchor.

Side views of the pitcher illustrated in fig. 10. Note the marked differences between the two renderings of the same ship.

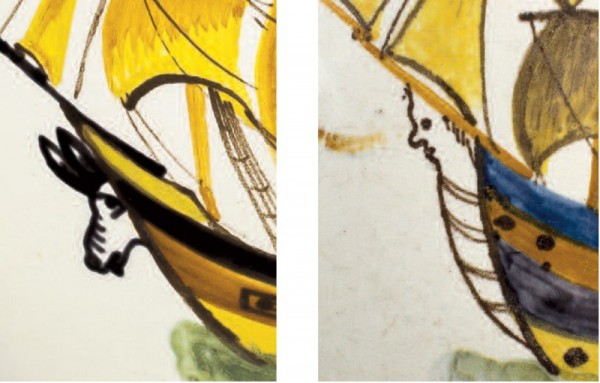

Figurehead details of the Hopewell (left) and the Venerable (right).

English and Scottish flags at the sterns of the Hopewell and Venerable.

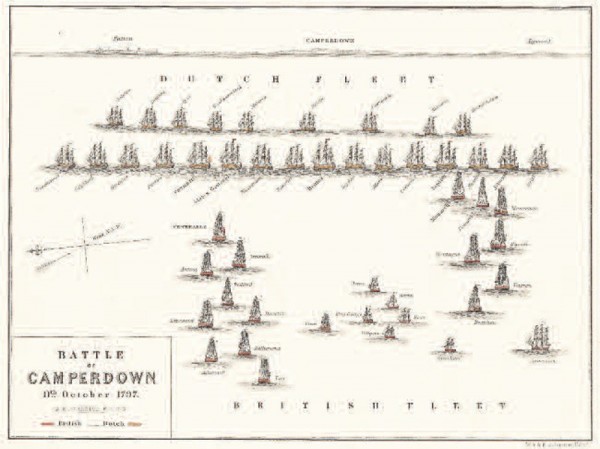

Battle of Camperdown, 11th October 1797, hand-colored engraving by A. K. Johnston F.R.G.S., published by William Blackwood and Sons, Edinburgh and London, 1848.

Thomas Witcombe, Battle of Camperdown, 1798. Oil on canvas, 35" x 53". (© National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London.) This is one of several paintings of the Battle of Camperdown, showing the blue-flagged Venerable at the center of the action alongside Admiral Van de Winter’s flagship.

Detail of the floral decoration painting on the puzzle jug illustrated in fig. 1.

Photograph of a pearlware puzzle jug attributed to Leeds, dated 1799 and with a foot similar to that of the Bloome jug. Reproduced from Oxley Grabham, Yorkshire Potteries, Pots and Potters (1916; reprint, Wakefield: S. R. Publishers, 1971). Once in the York Castle Museum, the jug is now missing.

“Publish or perish” is one of the oldest clichés in the academic lexicon, but in ceramic research publishing can do more harm than good. If we see it on paper we are inclined to believe it and to pass it on as truth. As with a bad brick, any wall built with it will eventually fall down, but not until the brick maker has left town and no one can be sure which brick was the culprit. In my own work I have taken the view that it is better to publish what one erroneously thinks is right than not to publish at all—even if other students and collectors are allowed the joy of finding the errors.

That mea culpa–ish introduction brings me to rewriting the story of John Bloome’s puzzle jug, which I had believed to be hiding the evidence of a secret romance (fig. 1). For forgetful readers of the 2014 issue of Ceramics in America, it goes like this: along with Bloome’s name, the pearlware jug is decorated with a well-painted portrait of a late-eighteenth-century merchant ship.[1] Across her stern is an identifying Hopewell and, below, the name “Wells” (fig. 2). To the left of “Wells” is what I took to be a heart-pierced arrow, suggesting that Mr. Wells was declaring his love for someone. Or was someone recording her love for Mr. Wells? And where did John Bloome fit into that scenario?

That was not the jug’s only secret. Puzzle jugs had been a tavern joke since the Elizabethan era, first in lead-glazed earthenware, then in delft and later in other wares from white salt glaze to brown stoneware. As figure 3 shows, they continued to be made into the mid-nineteenth century. This dated 1849 example in yellow-glazed earthenware is attributable to Yorkshire’s Ferrybridge Pottery. The joke centered on the number of spouts that the drinker had to cover to control the flow. The majority had three, though some had as many as six, theoretically making imbibing even more difficult. Why novice drinkers should continue to fall for the same trick across three centuries is hard to explain—as is John Bloome’s jug that has but one spout. Was he a simple fellow who could not cope with more?

Support for that assumption was offered by the jug’s painter. Below the bowsprit, where most ships braved the waves behind figureheads carved with mermaids, pulchritudinous maidens or heraldic beasts, the Hopewell displayed the head of a jackass (fig. 4). One immediately asks, “Did the ship really sail under an animal renowned for its stupidity?” Much more reasonable can be the conclusion that she only acquired that figurehead from the hand of the pearlware painter. In putting the single spout and the jackass together on a jug made for a specific individual, someone wanted to tell John Bloome that he was an idiot. So who could that be?

My answer claimed it to be one of two people, either a failed business partner or his wife. Had Bloome invested her money to buy or lade the Hopewell for a disastrous voyage, her annoyance might have been expressed in ceramic terms. Or, one might read a tavern mug as a gift from a man. When I published these speculations, British local historian Michael Welland made no bones about saying that unless they can be established as fact, “I don’t see how it can be written into an article.”[2] He also reminded me that “isolated records do not necessarily illustrate what was happening.” That, of course, is true of any assemblage of historical documents, be they state papers or an inscription on a pearlware jug. Much more pertinent was Welland’s blast that blew away my straw-built Ziggurat. My amorous Wells turned out to be the name of the Norfolk town where John Bloome lived, and the Hopewell was one of several trading vessels he owned to carry Yorkshire goods from Hull to Wells and on to Holland and Germany (fig. 5).

The scope of the Hopewell’s cargoes was laid bare on March 8, 1782, when she ran aground and broke up off the Norfolk coast. The Norfolk Chronicle reported that “On Wednesday morning last the Hopewell of Wells, John BLOOM Master, bound from Hull to the above port, laden with wheat, iron, cheese, earthenware etc. was drove onto Overstrand Beach, three miles from Cromer, in a hard gale of wind. The crew and part of the cargo was saved, but the vessel is entirely lost.”[3] The Norfolk coast with its tourist-appealing sands was a trap for wind-blown vessels, which, once grounded, were soon battered to pieces by the wind and sea that stranded them (fig. 6).

Was this the disaster that prompted John Bloome’s puzzle jug to be made? It seemed reasonable until one went beyond the painting to the pearlware body to be reminded that it was not in general production until two years later; nonetheless, the jug seems to be an example of pearlware at its best. The answer had to be that Bloome christened another Hopewell, perhaps dating as late as the 1790s. Under the heading of Hull traders The Universal British Directory of 1793 listed “Hopewell, John Bloom, King’s Coffeehouse, Hull,” thus proving beyond doubt that the puzzle jug related to a later Hopewell and not to the wreck of 1782.[4]

With that established one asks, what can we learn from the painted ship? Was the artist working from a drawing of the Hopewell or was he painting a generic merchantman and adding only the figurehead? Naval historian Sean Kingsley has described the rendering as “quite a large ship by the size of the aftcastle with four cabin windows.” She is shown with four of eight guns plus a stern-mounted salute swivel in the process of being discharged. The presence of the armament is a reminder that eighteenth-century commerce had more to face than boisterous seas and treacherous sands.

The North Sea (which Europeans called the “German Ocean”) was renowned for its storms and the presence of French pirates who preyed on merchantmen plying between England and the Continent. On June 2, 1744, the Charlotte sailing with four other Wells vessels was attacked by a Frenchman mounting ten cannon, eight swivels, and a crew of seventy-five. The Charlotte carried only four three-pounder cannon, two swivels, and a crew of seven, three of them boys. Repelling two attempts to board her, the Charlotte’s gunner scored a lucky hit on the Frenchman’s powder store with explosive results.[5] Had the boarding been successful, the pirates would have discovered that the Charlotte was carrying only a cargo of wheat.

That engagement was but one of the many that plagued the North Sea to the end of the century, when Hull merchants appealed to the Lords of Admiralty to provide a thirty-two-gun frigate to escort their convoys. The Dutch already had two to protect their ships carrying exports to England. John Bloome could not afford to put to sea unarmed. Even so, England’s short-trip export trade remained a hazardous undertaking—as old newspaper reports and modern scuba divers can attest.

The inclusion of earthenwares in the Hopewell’s lost cargo opens a new avenue of research, another of those curious coincidences that litter the rocks and eddies of maritime and ceramic history.

The first question to ask is, “What did John Bloome mean by ‘earthenware’?” Through most of the eighteenth century the term was used in two words, “earthen” and “ware.” In an account of the Low Countries published in 1672, the town of Delft was said to produce “Earthen Ware as stone-jugs, Pots, etc.” In 1792, however, a notice explained that “when earthen ware is mentioned in this paper the cream-coloured or queen’s ware is meant.” Another reference defined “earthen ware” as being products of Staffordshire, Nottingham, and Kent. The assumption, therefore, is that the term meant virtually any mid- to late-eighteenth-century ceramics being exported from Hull via Wells. Regardless of the 1672 reference to Delft potters making stoneware, it is reasonable to deduce that English delftware was not part of John Bloome’s cargo but was, instead, the English creamware often found in Dutch excavations. The 1793 Directory confirmed that “the town of Wells had a tolerable good trade with the Dutch in pottery.”

The next question relates to the source of Bloome’s ceramic cargo. We know it was being shipped from Hull, but was it the work of Hull potters? The 1793 Directory listed “no manufactories in the town” other than those directly associated with the shipping industry. However, the sage of English ceramic history, Llewellyn Jewitt, was confident that potters were working in the vicinity of Hull in the late seventeenth century. In a deed of 1802, Shelton potter Job Ridgway went into partnership with Hull potters James and Jeremiah Smith. Unfortunately, no examples of the Smiths’ wares are known. However, Jewitt cited a dinner service made for the owner of the Baltic trader Crow Isle to commemorate that ship’s encounter with the noted American pirate John Paul Jones off the Yorkshire coast in 1779. Jewitt noted that only one plate from the service was known to have survived and it was in the Hull museum.[6] Although it was likely to be of transfer-printed creamware, there was a remote possibility that it was of hand-painted pearlware or, as it was then called, “china glazed.” The museum reported that the plate had been destroyed in World War II, though a poor-quality photograph published in 1916 proves that the plate was, in fact, creamware (fig. 7).

Bloome may have purchased his earthenware in Hull. The port’s export trade was extensive and, thanks to the canal system and improved roads, goods intended for Europe could be carried overland from as far away as Bristol. In the words of the 1793 Directory, “most of the trade of Leeds, Wakefield, Huddersfield, and Halifax is negotiated here.” Of those, only Leeds earned fame as a potting center and for manufacturing a wide range of pierced creamwares. By the time that Jewitt was writing in 1872, the whitened “china glaze” was dismissed as “white ware.” Consequently, there are no confirming references to pearlware in the early Leeds records. With that caveat aside, it was reasonable to attribute John Bloome’s puzzle jug to Leeds. The distance from Hull to Leeds is approximately fifty miles, in modern terms a short trip but in the eighteenth century hardly worth the travel time to order one jug. It is probable, therefore, that somewhere in this mystery there was an agent selling Leeds products in Hull and that it was he who carried the Bloome request to the factory.

Building on that shaky assumption, one returns to the primary questions: Who placed the order and why? In 1792 John Bloome married his second wife, Ann Richardson, who was said by Michael Welland “to be an extremely wealthy woman, a multi-millionaire in modern terms.”[7] It seems unlikely, therefore, that she would have stooped to puzzle jug imagery over a financial setback. It is equally improbable that she would have misspelled her husband’s name.

Throughout his adult life John’s name was printed as bloom, as were those of other family members. Welland considers the misspelling no more than the kind of slip common in handwriting in the eighteenth century, but the consistent absence of an “e” can be significant. It suggests that whoever placed the order knew Bloome in person but not in writing. This might well have been either a business partner or a rival who suffered a loss due to Bloome’s stupidity and enjoyed direct or indirect contact with the Leeds pottery. If that be true, it is unlikely that the artist’s drawing accurately portrayed the lines of the Hopewell. The trick was to prove it.

In 2004 the Bloome jug was offered for sale by the late Jonathan Horne at the annual New York ceramics fair. He failed to find a buyer, nobody having been intrigued by the Hopewell’s enigmatic figurehead. Twelve years later Jonathan’s successor at the same fair, Garry Atkins, brought a ship-painted pearlware pitcher that undoubtedly was the work of the same artist (fig. 8). Even more valuable was its very precise date: October 11, 1797. The quality of the ware and the palette used to paint the Hopewell left little doubt that both jug and pitcher were of roughly the same age (fig. 9). Above the date on the front of the latter was a drawing of an anchor below “Duncan’s Glory,” which I first assumed to be the name of the ship (fig. 10). Had I been smarter (and my memory better.) I would have known that the date commemorated Admiral Adam Duncan’s victory over the Dutch at the Battle of Camperdown and that the painted vessel represented his flagship, the Venerable.

Bloome’s lightly armed Hopewell was clearly a merchantman, but on the pitcher Duncan’s man-of-war mounted thirty-four guns. More helpful was the artist’s decision to paint the ship twice, once with three masts and four cabin windows, and again with two masts and three windows (fig. 11). Therefore, Duncan’s painted warship bore no more resemblance to the real Venerable than Bloome’s did to the Hopewell. Duncan’s jug had yet more to tell us about Bloome’s jackass figurehead. In one version, the warship had no figurehead, and in the other it showed an appropriately scaled outline of a male head, this in contrast to Bloome’s jackass, which was drawn sufficiently out of proportion not to pass unnoticed (fig. 12). The red ensign flown by British merchantmen is fairly carefully drawn (the Union flag in its canon corner) at the stern of the Hopewell, but Admiral Duncan’s Venerable flew his own flag, namely, the St. Andrew’s cross on a white and blue ground (fig. 13). That might be read as showing that in the Battle of Camperdown the Scottish Duncan commanded both white and blue squadrons. He had been made admiral of the blue squadron in 1793 and of the white a year later.

A contemporary engraving shows twenty-five Dutch and French warships in a barricading line along the Camperdown shore against two prongs of the British attack (fig. 14). Led by the Venerable, Duncan’s naval forces broke through the Dutch line and attacked it from the rear. The water was shallow, prompting him to tell his officers that “when the Venerable goes down, my flag will still be flying.” His reference to “my” flag may have been to the Scottish flag on his pitcher, though it cannot be identified in the several paintings of the battle (fig. 15).

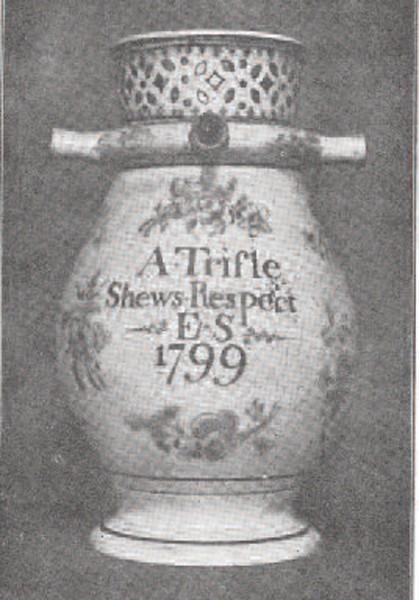

Duncan’s commemorative ceramics were never as plentiful as those made for Admirals George Rodney and Horatio Nelson. All but one of the Duncan souvenirs are of creamware, one hand-decorated and the others transfer-printed with portraits and battle scenes. The odd man out was described by ceramic historians John and Jennifer May: “Another painted piece is a pearlware jug . . . decorated on the one side with a ship in sail, on the other with a purely floral decoration but with, on the front, inside an open cartouche of laurels, the inscription ‘Admiral Duncan for ever.’”[8] That this small jug is only 5 1/4 inches in height makes it likely that its ship’s size is similar to that on the Bloome puzzle jug. Supportive, too, may be the floral sprig on the opposite side (fig. 16). Unfortunately, the whereabouts of the jug described by the Mays in 1972 are unknown and no illustration graces his excellent book. One likes to believe that when one’s treasures are given to a museum, they will be there in perpetuity, but changing times and new curators provide no such assurance. While seeking proof that the Bloome puzzle jug was a Leeds product, I found a book by Oxley Grabham, retired keeper of the York Museum, which illustrated a puzzle jug whose foot appears to parallel that of Bloome’s jug (fig. 17). Its floral decoration embraced the painted inscription “A Trifle / Shews Respect / E.S /1799.”[9] Attributing the dated jug to Leeds would provide Bloome’s jug with the evidence I needed. The author failed to confirm that the “E.S” jug was of pearlware or to provide any measurements. Nevertheless, he did say it was in the York Museum, but when I asked to see it I was told that no such jug was in its collection.

In spite of that dead end, the pursuit of John Bloome has atoned for the previous errors, if only to prove that an amorous Mr. Wells was not in love with Miss “X.” In any research we have a tendency to see the first discovered nugget to be the foundation for everything that follows. Only belatedly do we realize that that may not be so. My assumption that the Bloome jug was made in the 1780s had meant that it preceded the Duncan commemoratives. Wrong again!

A Yorkshire pottery factory (probably Leeds) had perfected the making of pearlware by the mid-1790s and was including the hard-to-make puzzle jugs when the Battle of Camperdown provided the impetus to create a line of Duncan-related souvenirs. When the victory fervor faded, the factory went on making name-identified puzzle jugs. In 1797 or soon after, someone in the Hull shipping business saw one of the Duncan ship jugs and applied to the factory to make another for John Bloome.

The lucrative export trade of the 1780s faded with the outbreak of the Napoleonic Wars and one by one the shippers of Wells and Hull went bankrupt. As long as John Bloome’s wife, Ann, remained alive, he had a financial buttress against his losses. But the good times had not returned when she died in 1805. Her will had been written prior to her marriage to John in 1795 and had not been updated. In it, she had left her assets to cousins and grandchildren. Of her two trustees, one had died and the other excused himself. With the will unproved, John went on spending her money until halted by extended legal action. In 1827 the court ordered him to return the money. Being unable to do so, his assets were put up for auction as “The Property of a Gentleman retiring from Business.” He died two years later.

Were it not for an accident of survival, the career of earthenware trader John Bloome of Wells-next-the-Sea would be forgotten, as would nearly everything else that happened in the year 1797. Collectors who only aspire to own or admire ceramic treasures are liable never to look beyond the object to the hand that held the cup or the yokel who made a fool of himself by spilling the puzzle jug. Yet, in truth, we are within a hand’s touch or a lip’s sip of them both. If, in our imaginations, we see a happy group of tavern revelers or a cheering crowd welcoming the return of the Venerable, we might do well to remember the underlying mood of the British people in 1797. Embroiled in a seemingly endless war with France and the Netherlands, humiliated by the loss of her American colonies, “the aspect of public affairs afforded nothing to cheer the minds of the people. On the contrary, the ill success of our negotiations seemed to preclude a hope of terminating the present most destructive war with honour and advantage.” The French are “our inveterate foe, breathing the most rancorous malice, and increasingly in strength from the desertion of our weak or perfidious allies.”[10] The message on Duncan’s jug reminds us that in the twenty-first century glory is as fleeting as the sight of a jackass on a puzzle jug.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The author is deeply indebted to Norfolk historian Michael Welland for much valuable informationt; also to maritime historian Sean Kingsley and stoneware authority Philip Mernick, who helped keep the Hopewell afloat.

Ivor Noël Hume, “The Ten Commandments,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University of New England Press for the Chipstone Foundation, 2014), pp. 2–18.

Welland, personal communication, November 16, 2015.

Norfolk Chronicle, March 23, 1782.

The Universal British Directory of Trade, Commerce and Manufacture, 5 vols. (London: British Directory Office, 1793), 3:338.

Norfolk Courant, June, 16, 1744.

Llewellynn Jewitt, The History of Ceramic Art in Great Britain, 2 vols. (New York: Scribner, Welford, and Armstrong, 1878), 1:464–66.

Welland, personal communication, November 16, 2015.

John May and Jennifer May, Commemorative Pottery, 1780–1900: A Guide for Collectors (London: Heinemann, 1972), p. 90.

Oxley Grabham, Yorkshire Potteries, Pots and Potters (1916; reprint, Wakefield: S. R. Publishers, 1971), p. 59.

Charles Mayo, A Compendious View of Universal History, from the Year 1753 to the Treaty of Amiens in 1802, 4 vols. (Bath, Eng.: Printed for G. and J. Robinson, 1804), 4:1.