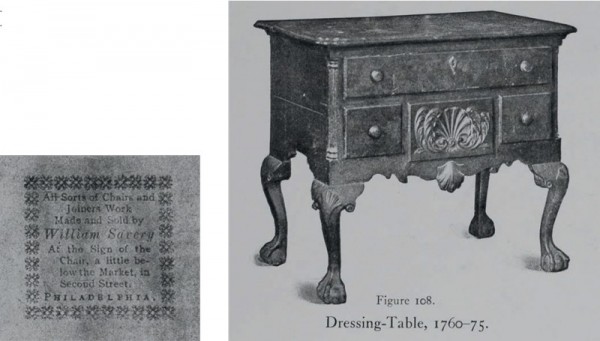

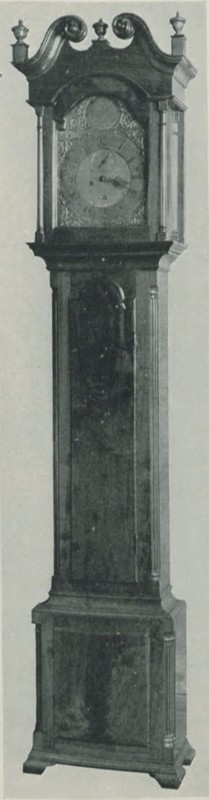

Figures 108 and 108a from Luke Vincent Lockwood, Colonial Furniture in America (New York: C. Scribner’s Sons, 1913), p. 110.

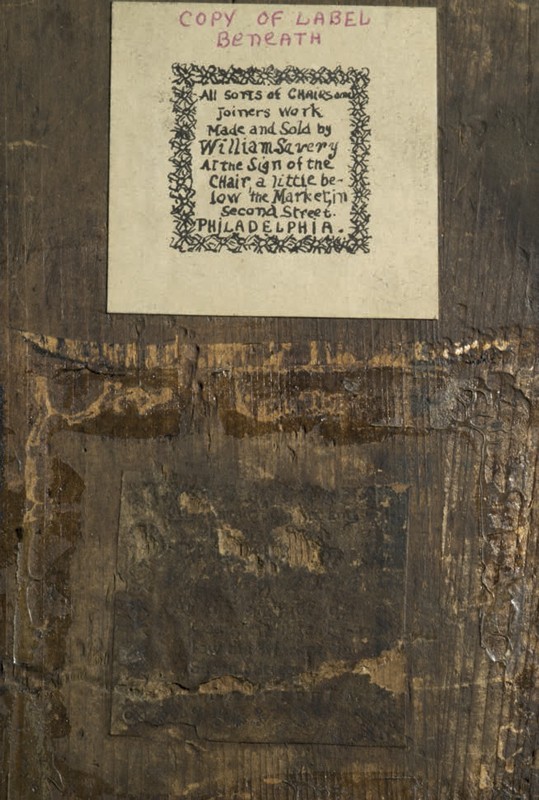

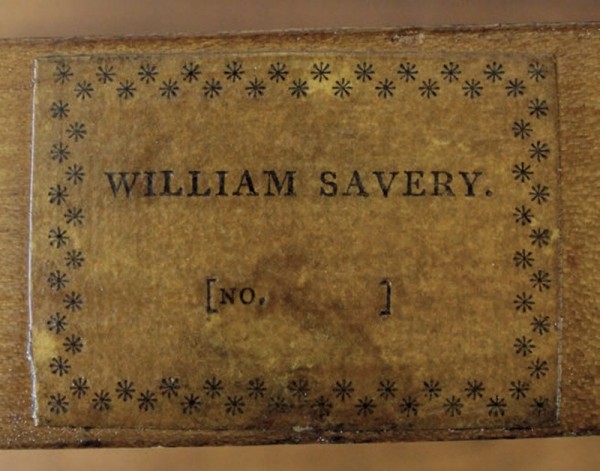

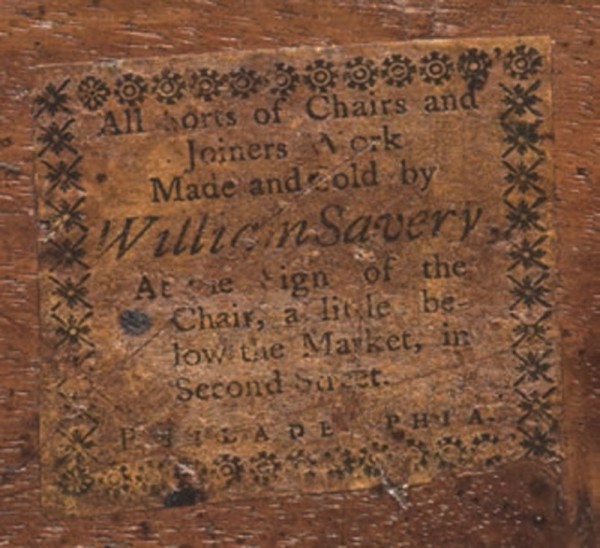

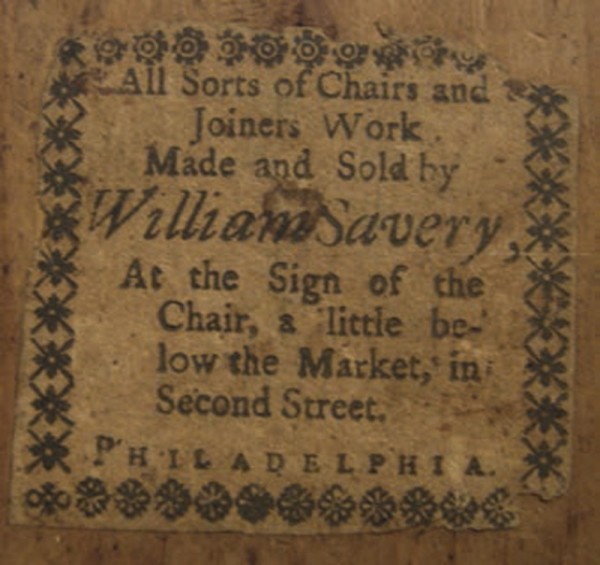

Detail of the late 1770s label attached to the bottom of the top drawer of the dressing table illustrated in fig. 3.

Dressing table by William Savery, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, late 1770s. Walnut with tulip poplar and white cedar. H. 30 3/4", W. 34 5/8", D. 21 1/4". (Courtesy, Van Cortlandt House Museum and the National Society of Colonial Dames in the State of New York; photo, Andrew Davis.)

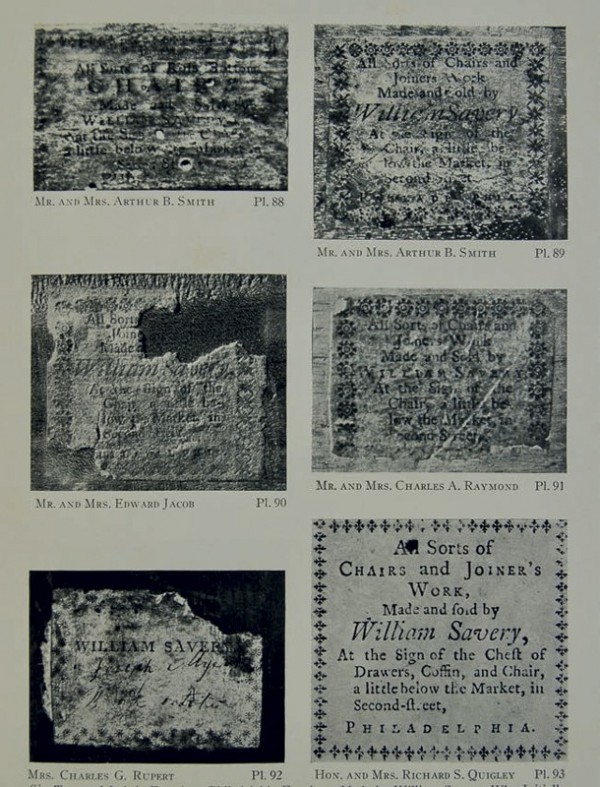

Plates 88–93 from William Macpherson Hornor, Jr., Blue Book, Philadelphia Furniture (Philadelphia: privately printed, 1935), showing six Savery labels.

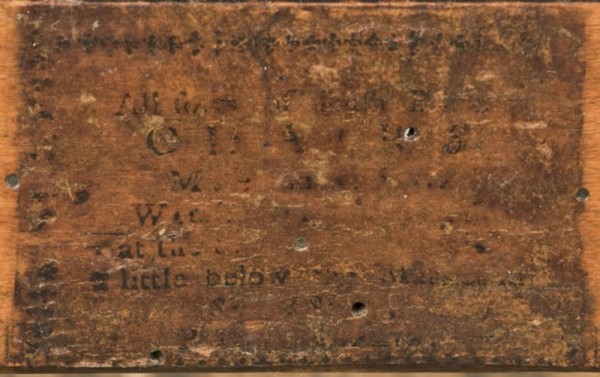

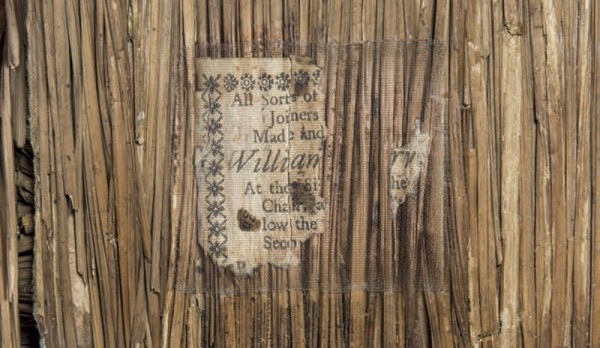

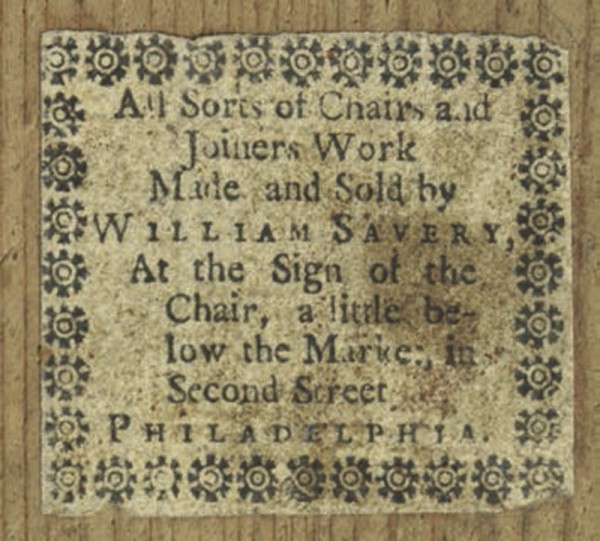

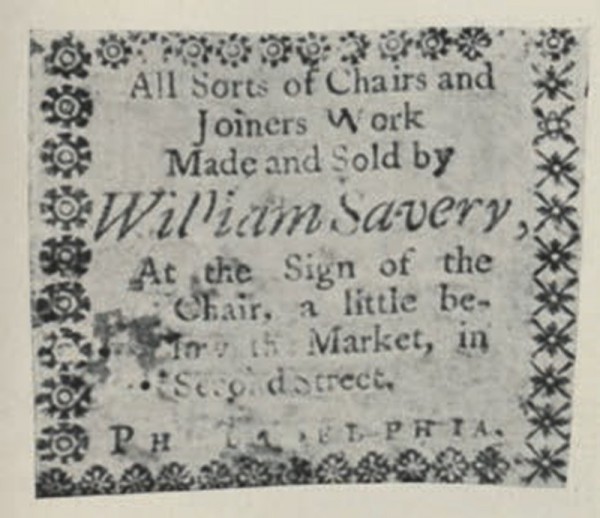

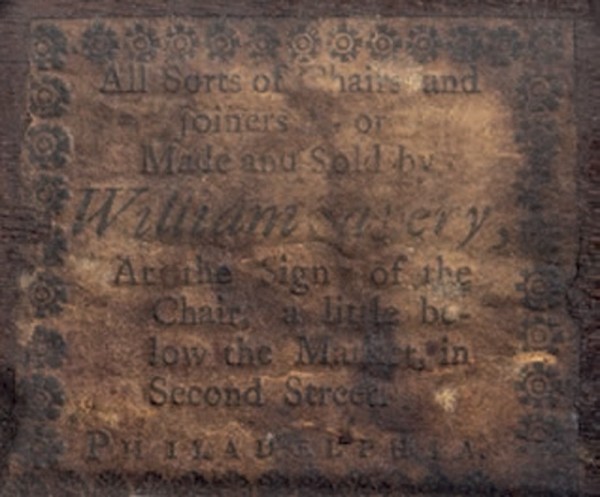

Detail of the ca. 1760 label on the side chair illustrated in fig. 6. This label is pl. 88 in Hornor’s Blue Book.

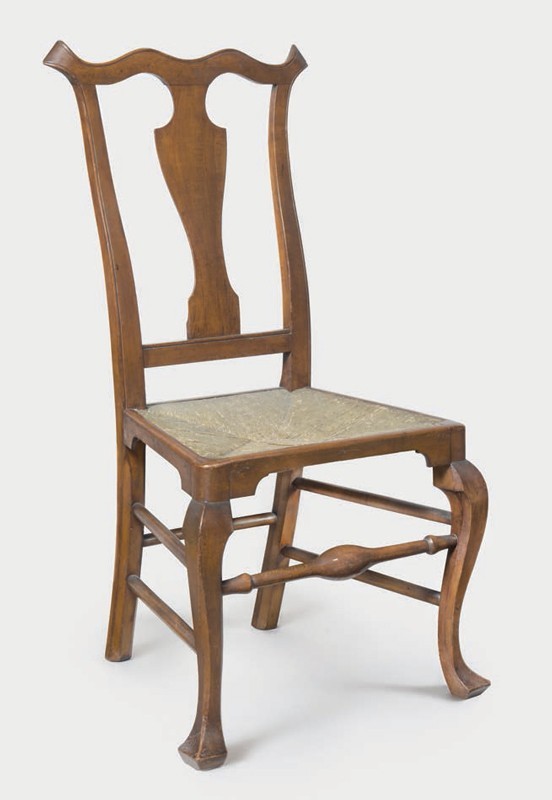

Side chair by William Savery, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1760. Maple. (Private collection; photo, Dallas Auction Gallery.)

Side chair by William Savery, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1775. Maple with Atlantic white cedar. H. 40 1/8", W. 21 7/8", D. 19 3/4". (Courtesy, Dietrich American Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the ca. 1775 label on the side chair illustrated in fig. 7. The label is attached to the underside of the rush seat.

High chest of drawers by William Savery, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1780. Mahogany. H. 94", W. 45", D. 24". (Private collection; photo, Sotheby’s)

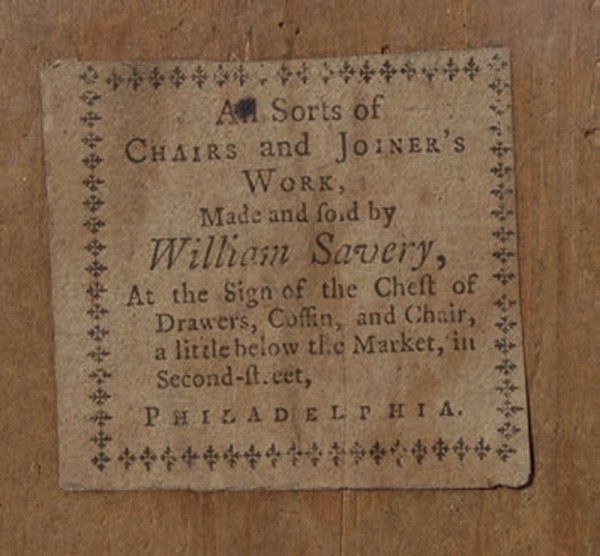

Label for William Savery’s shop at the “Sign of the Chest of Drawers,” Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1780. William Hornor published this label with the high chest illustrated in fig. 9, although it is on a slant-lid desk. The high chest bears a different strike of the same label. This label is pl. 93 in Hornor’s Blue Book.

Armchair by William Savery, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1780. Mahogany, with tulip poplar, hard pine, and white cedar. H. 37 3/4", W. 30 1/2", D. 24 1/8". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum; photo, James Schneck.)

Tall clock case by William Savery, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania ca. 1780. (Antiques 14, no. 3 [October 1928]: 310.)

Chest of drawers by William Savery, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1785. (Antiques 9, no. 2 [February 1926]: 77.)

Detail of the ca. 1785 label on the till of the chest illustrated in fig. 25. This label has Savery’s name only and is the same version illustrated as pl. 92 in Hornor’s Blue Book.

Detail of the ca. 1765 label on the desk illustrated in fig. 22. This label, which references joiners work and has Savery’s name in block letters, is pl. 91 in Hornor’s Blue Book.

Label of William Savery, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1765. This label, which references joiners work and has Savery’s name in italics and dingbat pattern 1, is pl. 90 in Hornor’s Blue Book. From Samuel T. Freeman and Co., The James Curran Collection of Rare Eighteenth-Century American Furniture, Philadelphia, March 11–12, 1940, lot 297.

Detail of the ca. 1770 label on the inside rear seat rail of the armchair illustrated in fig. 24. This label references joiners work and has Savery’s name in italics and dingbat pattern 2.

Label of William Savery, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1775. This label, which references joiners work and has Savery’s name in italics and dingbat pattern 3, is pl. 89 in Hornor’s Blue Book. It is on a desk. (Courtesy, Historic Odessa Foundation.)

Label of William Savery, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, late 1770s. This label, which references joiners work and has Savery’s name in italics and dingbat pattern 4, is from a privately owned desk. (Privately collection; photo by the author.)

Armchair by William Savery, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1765. Woods and dimensions not recorded. (Courtesy, Winterthur Decorative Arts Photographic Collection, 64.1766.)

Side chair by William Savery, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1765. Walnut. H. 39", W. 21", D. 20 1/4". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

Desk by William Savery, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1765. Walnut with tulip poplar and white cedar. H. 41 3/4", W. 38", D. 20 1/2". (Courtesy, Chester County Historical Society.)

Side chair by William Savery, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, late 1760s. (Courtesy, Winterthur Decorative Arts Photographic Collection, 64.1713.)

Armchair by William Savery, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1770. Walnut with yellow pine. H. 40", W. 29 1/4", D. 22 1/2". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum; photo, James Schneck.)

Blanket chest by William Savery, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1785. Walnut with tulip poplar and maple. H. 28 3/8", W. 48 1/4", D. 20 5/8". (Courtesy, Biggs Museum of American Art; photo, Carson Zullinger.)

Side chair by William Savery, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1785. (Courtesy, Winterthur Decorative Arts Photographic Collection, 1976.1036.)

In 1913 pioneer furniture historian Luke Vincent Lockwood published a Philadelphia Chippendale dressing table that had been recently installed in the Van Cortlandt House (1748) in the Bronx, New York, where it remains today. Lockwood also illustrated the label of its maker, William Savery, which was the first time an American furniture maker’s label appeared in print (fig. 1). The label now very much looks its age, but it may not have changed much over the last century, since its image had been cleaned up considerably for the 1913 publication (fig. 2). The dressing table has also been cleaned up since then; notably, the wooden knobs in the 1913 image have been replaced by style-appropriate brasses (fig. 3).[1]

Savery quickly assumed iconic status when, in 1918, New York City collector and museum trustee R. T. H. Halsey attributed most of the ornate examples of Philadelphia Chippendale furniture at the Metropolitan Museum of Art to the cabinetmaker in a Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin article. Not to be outdone, Samuel W. Woodhouse, Joseph Downs, and William Macpherson Hornor, all working in Philadelphia, attributed additional furniture to Savery based on newly discovered labels, paths of family descent, or for various other reasons. Along with providing new biographical information, some of these articles, published between 1923 and 1930, reassessed Savery’s work as being more modest than the “superlatively fine work” heretofore so freely ascribed to him. Despite this downward revision, Savery remained in the forefront of early American furniture makers. Although times have changed, Savery continues to attract substantial attention in the marketplace, and ongoing attributions build on the enthusiasms of these early writers.[2]

This study draws on thirty labeled Savery pieces of furniture, some of which are known only through photographs. A few other pieces, reportedly with fragmentary labels, have been omitted until they can be located and studied. Furniture makers’ labels represent one of the more certain means of maker identification. These Savery-labeled objects represent the largest group of colonial American furniture documented to one maker by such evidence.[3]

In 1935 William Hornor published six different Savery labels in the Blue Book (fig. 4). None of the printed labels is dated, nor can any be dated precisely by external evidence, such as an original bill of sale accompanying the particular labeled piece of furniture, a date written on a labeled object, and so forth. Hornor opined “but from these [labels] (since they are not dated) nothing can be deduced, as Savery was continuously located ‘a little below the market in Second Street’ [that is, the address given on the labels] during his long career.” Nonetheless, Hornor set the six labels in an order on the page, beginning with what is certainly Savery’s earliest label, designated as plate 88, in the upper left corner. Hornor ended with the plate 93 label, which references Savery’s shop at the “Sign of the Chest of Drawers, Coffin, and Chair, a little below the Market, in Second-street.” The address was the same, but the new shop sign was no longer just the “Sign of the Chair.”[4]

Although none of the labels can be precisely dated, the various pieces of furniture on which they were used provide ample evidence and clues to position the undated labels in correct chronological sequence. Each group of furniture, unified by the particular Savery label, represents a distinct, chronological body of work from Savery’s shop. Comparison of each piece of furniture within each labeled group to other Philadelphia examples and to documentary evidence in general establishes informative date ranges. Finally, merging all of those findings with the facts of Savery’s life generates timeframes for the use of each label type. Although the resulting date ranges are not exact, their general timeframes yield important observations about Savery’s output and furniture making in eighteenth-century Philadelphia.

The Earliest Label

Only a single example of the Savery label that Hornor placed first survives. It reads “All Sorts of Rush Bottom | CHAIRS | Made and Sold by | WILLIAM SAVERY | at the Sign of the Chair | a little below the Market” followed by an illegible section that likely identifies “Second Street,” his long-standing street address, and “PHILADELPHIA.” Significantly, this label is the only one that references rush-bottomed chairs, such as the side chair on which it is applied (figs. 5, 6). Subsequent labels describe Savery’s offerings as being significantly more varied by advertising “All Sorts of Chairs and Joiners Work.” The one other label bears only his name.

All evidence related to the label on the rush-bottom chair, that piece of furniture, and Savery’s biography confirm that this label was the first one he used. Chance survival of a hand-written receipt documents Savery’s training as a maker of inexpensive turned and rush-bottomed chairs. In 1741 he signed a note for £3.18 from John Wister “for the use of My Master Salomon Fussel & me.” Although nothing identifies the purpose of this payment, it unequivocally identifies Philadelphia turner and slat-back chairmaker Solomon Fussell (1704–1762) as Savery’s master. The precise nature of Fussell’s craft is thoroughly detailed by his ledger book, which covers the years from 1738 to 1749. As for Savery’s biography, no birth record is known. He died on May 27, 1787, and a death record put his age at sixty-five. Arithmetic sets his birth between May 1721 and May 1722. When he reached his majority in 1742 or 1743, marking his transition from apprentice to adulthood and wage-earner, the furniture he made must have reflected his training. Five other rush-seated chairs, including one slat-back chair, survive with other Savery labels. They show slight differences in the front stretcher, placement of side stretchers, shape of the crest rail, and shape of the splat (figs. 7, 8). Based on stylistic comparisons among all of these labeled chairs, the one bearing the rush-bottom label represents the earliest chair. Thus the wording of the labels, Savery’s biography, and style analysis all reinforce the conclusion that this label was the first one he used.[5]

When were these chairs made, and by inference, what is the approximate date of that first Savery label? Numerous published works date the labeled rush-seated chairs—whether with round-shouldered or eared crests—from 1742 to 1750 or 1760. Although ample historical evidence supports this date range for the general chair design, that kind of analysis does not necessarily apply to Savery’s first or subsequent labels. In fact, it is inaccurate. The problem derives from the complete absence of printed labels used by any American furniture maker in 1742, or anytime until the late 1750s. The earliest datable American label is that of New York upholsterer Joseph Cox, used between 1757 and 1760 when he worked on Dock Street. John Elliott (also regularly spelled Elliot), another early user of labels in America, arrived in Philadelphia in 1753 from Leicester, England. There, he had used a printed label proclaiming himself to be a cabinetmaker, chairmaker, joiner, and turner, who also repaired looking glasses. Upon arriving in Philadelphia, Elliott continued to work as a furniture maker. He began advertising regularly in newspapers in June of 1756, describing himself as “John Elliot, Cabinet-maker” on Chestnut Street with looking glasses for sale. Sometime between June and November, 1757, he changed his business name to “Elliot’s Looking-glass store.” By the following April he had changed the description of his business location to “the Sign of the Bell and Looking Glass.” This same wording appeared on his first American label, indicating that he probably started using labels in Philadelphia about that time, namely 1758.[6]

Savery’s career suggests that he was a plodder, slow and steady, rather than a marketing prodigy. Of his early career we know only that in a 1750 newspaper notice, in which he sought the owner of a fowling piece, he called himself “William Savery, Chair-maker in Second Street.” He made no reference to “Joiners Work,” a phrase that featured prominently in his subsequent labels. There is no firm answer to when Savery had his first labels printed. Based on all available evidence of label use in America, the prudent historian favors circa 1760, which places Savery’s use very early, but not at the very start. In contrast, enthusiastic furniture historians, citing style analysis and style conventions associated with rush-seated chairs, and ignoring the need to explain exceptional and pioneering behavior on Savery’s part, have opted for the mid- to late 1740s, and no later than 1750. All things considered, 1758 or 1759—putting Savery with Elliott and Cox, but not before—probably best balances historical veracity with broader acceptance among furniture historians, at least until additional historical evidence comes to light.[7]

The Late Labels

The label that Hornor listed last, namely the one that references a new shop sign—“At the Sign of the Chest of Drawers, Coffin, and Chair”—appears on seven pieces of furniture. A high chest of drawers, with its pierced pediment, is stylistically the latest piece of furniture within that group (figs. 9, 10). Other pieces of furniture within the group include a pierced-splat joined armchair, a tall clock case (whose whereabouts is unknown), and case furniture without much style-sensitive decoration (figs. 11, 12). However, comparison of this furniture to the three known objects bearing Hornor’s fifth label, which records only Savery’s name, yields interesting results. That group includes Savery’s only known serpentine-front chest of drawers (figs. 13, 14). The first datable instance of the serpentine shape in American furniture occurred in a bill from furniture maker Benjamin Randolph of Philadelphia to Colonel George Craughan, dated April 2, 1765, for “a Comade [commode] Buroe Table” priced at £15. The term “commode” denoted a serpentine-shaped front. The next occurrence was in 1771 when John Cadwalader bought from Thomas Affleck “2 Commode Card Tables” and “2 Mahogany Commode Sophias for the Recesses” as part of a large furniture order. The 1772 Philadelphia Prices of Cabinet and Chair Work reinforces this timeframe by describing a “commode dressing table, with four long drawers.” Thus the two furniture groups defined by Hornor’s labels five and six each include pieces of furniture that must postdate the late 1760s. Further stylistic analysis of the furniture within those two groups is inadequate to determine the correct label order, underscoring the need to consult other kinds of evidence.[8]

Consideration of the wording and typography of all the Savery labels introduces new and useful perspectives. Several labels use the same wording: “All Sorts of Chairs and | Joiners Work | Made and Sold by | William Savery | At the Sign of the | Chair, a little be- | low the Market, in | Second Street. | Philadelphia.” Their differences lie in minor typesetting and typeface changes and the dingbats (or printer’s ornaments) that border the text. Given Savery’s training as a turner and slat-back chair maker, these labels that reference joiner’s work must have come after the “rush-bottom chair” label. None of the furniture bearing any of these labels displays late style features comparable to the pierced pediment high chest or the commode chest. Consequently, these similarly worded labels must predate the new shop sign label and the Savery name-only label. Chronological placement of the name-only label earlier than the new shop sign label—as Hornor asserted—interrupts the continuity of typography and wording between the new shop label and the middle group; the wording is identical among all except for the additional words that describe the new shop sign. The name-only label, in contrast, exhibits a completely different message and new graphics (and likely represents work of a different printer than the first seven labels). It has no address; instead, it provides a space for a number to be inked in. Placing it last resolves the issue of consistent typography without creating new problems derived from the dating of individual pieces of furniture on which it or the new shop sign label appear.

The name-only label raises the question of what might have happened to cause such a radical change in graphics and message. In it, Savery no longer identifies himself by what he did, nor does he list his place of business. He may have changed printers for some unknown reasons, but other events may also have intruded. Over the course of Savery’s career, he steadily diversified his furniture-making capabilities from turned chairmaking to incorporating joinery, and later, to cabinetmaking. Yet he still called himself “joyner and chair-maker” in his will of 1783, suggesting that as he neared the end of his life (he died four years later), he still viewed himself as the artisan he had been decades earlier. However, three events in his later life may have affected his career trajectory: a serious fire in 1772; his allocation of space in his house for the sale of textiles and more general merchandise in the years following the fire; and the Revolutionary War.

At daybreak on January 30, 1772, Savery’s house and shop caught fire as flames spread from an adjoining house. According to a newspaper notice, the upper story and roof were “consumed” and he suffered “pretty considerable” loss of “household-furniture, merchandize, &c.” This disastrous event occurred while Savery was still filling furniture orders for John Cadwalader, who recently had completed his elegant town house two blocks south on Second Street. Given the timing of Cadwalader’s bills, Savery must have recovered quickly from the fire, but the potentially devastating loss of earning power it represented may have shocked him into seeking alternative or supplementary sources of income. In any event, newspaper advertisements in December 1772 and March 1777 told Philadelphians that they could get more than just furniture at his address: Joshua Brook, “Just arrived from England, with a neat assortment of coarse and fine FOREST CLOTHS, dressed and shaged, all of his own manufacture” along with cutlery. In a similar advertisement in 1777, Henry Johns offered a long list of writing and other goods at Savery’s house. The Revolutionary War must also have added uncertainties to Savery’s working life and circumstances, although nothing points to specific changes. Given all available evidence, the generic, multi-purpose label seems to have fit the more varied conditions that came into play toward the end of his life.[9]

Before investigating the remaining Savery labels, one final note pertains to his latest, name-only label. In 1934 this label was published as a fake in American Collector, the author stating “these cabinetmakers’ labels [referring to ones naming Savery and James Gillingham] fall so far short of resembling the originals that they can be readily recognized by anybody who has once seen the genuine.” Indeed, the author’s comparison to the label published by Lockwood (see fig. 1) shows no common ground, but aside from this disparity, there is no reason not to accept as authentic the three other surviving examples of the label. The concern that this article engendered in the marketplace then, and in the decades since, has been misplaced. Other fake Savery labels exist (but are beyond the scope of this essay). They include both photographic reproductions and entirely made-up examples.[10]

The Middle Labels

Establishing a sequence for the remaining labels, all of which have identical wording, begins with comparing the groups of furniture on which they each appear. The eleven objects represent a range of furniture forms and levels of embellishment. The seven chairs include inexpensive rush-seated examples as well as framed chairs, one with Marlborough legs and another with carved claw-and-ball feet and shell-carved knees. The other objects include the dressing table illustrated in figure 1, a dished-top tea table, a chest of drawers, and a slant-lid desk. Unlike furniture bearing the late labels, however, none of this furniture exhibits features with definable timeframes. Moreover, Hornor gave no justification for his order, shown in figure 4. Consequently, sequencing these labels requires other approaches.

Graphics on the labels reveal two useful attributes. First, Savery’s name appears either in italics or in block letters. Second, the dingbats bordering the labels differ. Closer attention shows that alignment of some letters also changes corresponding to the dingbat changes. In fact, there are two more labels than the three that Hornor illustrated in plates 89–91. Only one of these five identically phrased labels has Savery’s name in block letters (fig. 15); four labels show it in italics with varying patterns of dingbats and slight changes in letter alignment, which argues for separate print runs of otherwise very similar labels (figs. 16-19).

Extending the consistency of wording among all of these labels to their typographical properties yields one clear result. The single block-letter label, which Hornor placed last among these middle labels, belongs second, immediately after the rush-bottom chair label, also with block letters. The group of furniture bearing this label, then, would be his second group. Among the eight so-labeled pieces of furniture is the only other Savery-labeled, rush-seated maple chair with round shoulders and yoke-crest, like the single example bearing the rush-bottom chair label in figure 6. This chair-related evidence alone argues that this label followed the first. In the group is also the rush-seated slat-back armchair (now with rockers), a seating form detailed often in Fussell’s ledger book (fig. 20). Two framed chairs among the eight, a walnut side chair (fig. 21) and a privately owned maple armchair, each representing a more expensive object than rush-bottom chairs, not only have early-styled crest rails with rounded ears but display Savery’s label on the outside of the rear seat rail—as occurs on several rush-bottom chairs—rather than inside the rear seat rail, which is the usual place in joined chairs. The other four objects with this second label include three chairs, each of which can be stylistically dated among the earlier Savery labeled furniture, and a slant-lid desk, representing the earliest documented example of Savery’s cabinetry (fig. 22). The desk lacks any time-specific design features and is similar to two other Savery desks bearing what are likely significantly later labels.[11]

The remaining four labels with Savery’s name in italics are the most difficult to sequence. Their respective groups of furniture do not include obvious candidates that can be compared to broader chronological developments in Philadelphia furniture, but small links within Savery’s work exist. For example, the label illustrated in figure 16 appears on three chairs only, one of which is a rush-seated chair with an urn-shaped splat, similar to an armchair bearing the second label shown in figure 14. Another, known only by its published image (fig. 23) and missing a medial stretcher and the outer mid-straps of the splat, has a distinctive arched piercing in the crest rail. That same piercing occurs in another side chair that may be part of the same set as the armchair bearing the label illustrated in figure 17 (fig. 24). Thus, the labels shown in figures 16 and 17 are likely consecutive. The Marlborough-leg feature introduces the opportunity to ask when this feature first appeared in Philadelphia furniture. The earliest use is in 1762 or 1765, depending upon how a chalk inscription on the slip-seat of a Benjamin Randolph armchair is read. Again, assuming Savery was not a style leader in Philadelphia, the label on the Marlborough-leg side chair must have been made sometime after 1762 or 1765. That timeframe conforms to the general order of the label illustrated in figure 17.[12]

Furniture associated with the remaining two italic labels (see figs. 18, 19) number seven pieces. They include the Van Cortlandt dressing table, an expressive rococo side chair (more ambitious than most Savery furniture), two other side chairs, another desk, a chest, and a tilt-top tea table. None of this furniture necessarily pre- or postdates that in the other two italic label groups, but taken together, these various furniture forms demonstrate significantly more ambitious cabinetmaking on Savery’s part. Over the course of his long career, he increasingly incorporated cabinetry into his furniture-making, which he highlighted with his new “Sign of the Chest of Drawers, Coffin, and Chair.” On that basis, and until more compelling evidence surfaces, these two labels are likely later than the other two italic labels illustrated in figures 16 and 17. When subdivided by label, these last seven objects fall into a group of two chairs and the tea table on the one hand, and one chair and three case pieces on the other. Following the same reasoning of more cabinetry later in Savery’s career, the sub-group with predominantly case furniture is later.

In sum, the sequencing of labels is:

1. The label on the side chair with rush seat illustrated in figure 5

2. The label with block letters illustrated in figure 15

3. The label in italics illustrated in figure 16

4. The label in italics illustrated in figure 17

5. The label in italics illustrated in figure 18

6. The label in italics illustrated in figure 19

7. The new sign label illustrated in figure 10

8. The name-only label illustrated in figure 14

Placing the Sequenced Labels on a Timeline

With the sequence of labels established, the final step is to plot the labels on a timeline. Savery’s working career began in 1742 or 1743, when he reached his majority, and ended with his death in 1787. The historical record does not disclose when he established his own shop, although that was likely before 1750 when he advertised the lost fowling piece and cited his own address rather than an employer’s. Given the evidence concerning furniture label use by all artisans in America, Savery’s earliest label did not predate 1758 or 1759. If the eight labels are spaced evenly across the remaining twenty-five or so years of his career, they can be plotted as shown on the upper timeline on table 1. The lower timeline shows the labels redistributed across the same timespan according to the number of surviving pieces of furniture bearing those labels. Given the small sample of surviving Savery furniture with labels (even though it represents the largest body of its kind in American colonial furniture), narrow adjustment or refinement of label dates is probably not justified. Nonetheless, furniture historians should acknowledge a few consequences of using an overly simple metric of a new label about every 3 1/2 years. Savery’s second label may have come sooner. For example, he might have acquired his joinery skills within the fifteen or more years that had already elapsed since he commenced and was eager to advertise them; or, only one object with the first label survives compared to eight for the next, suggesting the print runs may have been different sizes. Surely there was no “normal” print run for labels since they were a new product in America. Work during the Revolution must have slowed, especially during British occupation in 1777 and 1778. Some health-related circumstance must have caused Savery to write his will in 1783, when he was about sixty-one and unlikely to order new labels, even if they did not reference his furniture-making trade.

In the absence of specific claims for the dates of individual labels, what value remains to furniture historians? Sequencing the labels yields a much clearer—although admittedly imprecise—chronology of Savery’s work. The fifteen-to-seventeen years before Savery’s first label loom large and represent a timespan that many furniture historians want to populate with his labeled furniture. He certainly was making furniture at that time—but not those particular examples. The objects that happen to bear labels are later, but they can be used to indicate with reasonable accuracy what he made throughout that early period. Label sequencing improves the accuracy of dating his work, even while maintaining appropriate date ranges. In most instances, attention to label sequence moves commonly published dating back ten or fifteen years. Generalizing from these examples shows that once again the field of furniture history has misapplied style analysis to date objects as much earlier than datable historical evidence indicates.[13]

Attention to labels yields other results: based on their identical labeling, Savery’s shop produced the two chairs illustrated in figures 20 and 21 within a narrow timespan. Intellectually, the historian acknowledges that a shop—Savery’s shop—could supply simple or more complex furniture at any one time. But viewing these chairs side by side triggers the desire to separate them by a lot of time, reflecting Savery’s growing capabilities and reputation over the years. However, the labels tell us that that scenario is false. Similarly, two slant-lid desks that are identical inside and out carry Savery’s second and seventh labels, which likely separate their manufacture by almost twenty years. And finally, how might the objects shown in figures 25 and 26 have been dated if Savery’s latest label had been removed from them?[14]

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Among many who assisted with this article, the author thanks Deborah Buckson and Jennifer Kostik, Laura Carpenter, Tara Chicirda, Jim Green, Ryan Grover, Joe Hammond, Constance Hershey, Jerry Holley, Sarah Lewis, Susan Newton, Deborah Rebuck, Jeanne Solensky, and Jay Stiefel.

Luke Vincent Lockwood, Colonial Furniture in America, 2nd ed., 2 vols. (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1913), 1: 110.

R. T. H. Halsey, “William Savery, the Colonial Cabinet-Maker and His Furniture,” Bulletin of the Metropolitan Museum of Art 13, no. 12 (December 1918): 254–67.

Labeled John Elliott looking glasses surely outnumber Savery objects, but many of the former are English.

William Macpherson Hornor, Jr., Blue Book, Philadelphia Furniture: William Penn to George Washington (Philadelphia: privately printed, 1935), p. 202.

Benno M. Forman, “Delaware Valley 'Crookt Foot' and Slat-Back Chairs: The Fussell-Savery Connection,” Winterthur Portfolio 15, no. 1 (Spring 1980): 46, 41–64. A.W. Savary, Savary Family (Boston: Collins Press, 1893), p. 136.

Forman, “The Fussell-Savery Connection,”47–48, dated after 1742; Jack L. Lindsey, Worldly Goods: The Arts of Early Pennsylvania, 1680–1758 (Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1999), p. 98, dated 1745–50; Metropolitan Museum of Art online collection database, acc. no. 1994.410, dated ca. 1745. Cox advertised himself in Hanover Square, New-York Mercury, May 19, 1756, p. 3, through August 23, 1756, p. 4. He advertised the Dock Square address on May 9, 1757. For early American labels in general, see Philip D. Zimmerman, “Early American Furniture Makers’ Marks,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2007), pp. 136–38. Pennsylvania Gazette, July 15, 1756, p. 3; November 10, 1757, p. 4; April 13, 1758, p 5.

Pennsylvania Journal and Weekly Advertiser, November 1, 1750. Quoted in Alfred Coxe Prime, Arts & Crafts in Philadelphia, Maryland and South Carolina, 2 vols. (1933; reprint ed., New York: Da Capo, 1969), 1: 181.

Andrew Brunk, “Benjamin Randolph Revisited,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2007), p. 21, fig. 30. Nicholas B. Wainwright, Colonial Grandeur in Philadelphia: The House and Furniture of General John Cadwalader (Philadelphia: Historical Society of Pennsylvania, 1964), p. 44. Alexandra Alevizatos Kirtley, The 1772 Philadelphia Furniture Price Book: A Facsimile (Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2005), p. 18.

The Pennsylvania Packet; and the General Advertiser, February 3, 1772, p. 2. Ibid., December 21, 1772, p. 4. The Pennsylvania Evening Post, March 18, 1777, p. 1.

“Spurious Labels Now in Circulation,” American Collector 1, no. 3 (January 23, 1934): 1, 6. The published label has been annotated in ink, “Cleaned for Madame Biddel,” an inscription not on the three labels in this study. The Biddel furniture form is not identified in the 1934 article.

One labeled rush-seated chair among a set of six, in the collection of the State Museum of Pennsylvania, acc. no. 64-10. The slat-back armchair, which whereabouts is unknown, appears to have had rockers added later because of their shape.

W. M. Hornor, Jr., “William Savery: ‘Chairmaker and Joiner,’” Antiquarian 15, no. 1, (July 1930): 31.

For specific Savery characteristics, see Philip D. Zimmerman, “The ‘Boston Chairs’ of Mid-Eighteenth-Century Philadelphia,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2009), pp. 154–56.

The desks are the one in figure 22 and another published in Parke-Bernet Galleries, Important Eighteenth-Century American Furniture, New York, January 31, 1970, lot 165.