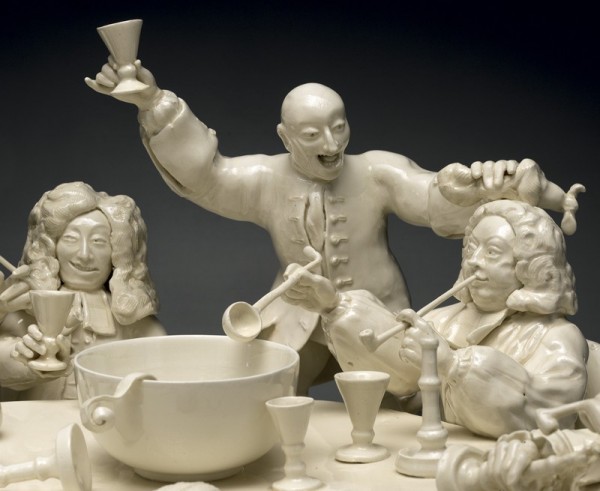

Detail of the figural group illustrated in fig. 3. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

William Hogarth, A Midnight Modern Conversation, London, England, 1733. Etching and engraving on laid paper. 15 1/16 x 20 1/2". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

Michelle Erickson, A Midnight Modern Conversation, Hampton, Virginia, 1999. Modeled and thrown creamware. W. 26". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Michelle Erickson, Van Gogh Puzzle Jug, V&A Residency, London, 2012. Tin-enameled stoneware. H. 10". (Collection of the artist; photo, Robert Hunter.)

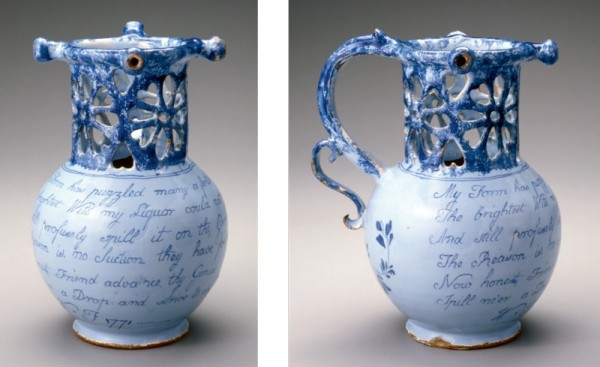

Puzzle jug, Bristol, England, dated 1771. Tin-enameled earthenware. H. 8 1/2". (Chipstone Foundation.) The jug is thrown and has at the rim a three‑nozzled tube connected to a hollow handle with an S-scroll at the base. The neck piercings include four flowers separated by pairs of hearts. The bottom is unglazed. Sponging decorates the neck, nozzled rim, handle, and S-scroll. Painted decoration includes a peony and a rhyme:

My Form has puzzled many a fertile Brain.

The brightest Wits my Liquor could not gain

And Still profusely spill it on the Ground

The Reason is, no Suction they have found

Now honest Friend advance, thy Genius try

Spill ne’er a Drop and strive to dr[ink] me dry

W [star] F 1771

Michelle Erickson, VANITAS, Bideford, Devon, England, 2013–2015. Sgraffito-decorated wood-fired slipware. H. 17". (Courtesy, William C. and Susan S. Mariner Collection; photo, Robert Hunter.) The jug was made with indigenous North Devon “Fremington” clay and North Devon ball clay slip. It was fired in Clive Bowen’s St. Ives Studio, Cornwall, England.

Side views of the jug illustrated in fig. 6.

Dish, North Devon, England, ca. 1670. Slipware. D. 12 1/8". (Courtesy, Collection of Colonial National Park, National Park Service; photo, Ceramics in America.) One of many nearly intact examples of North Devon sgraffito slipware recovered from archaeological excavations.

Erickson demonstrates the sgraffito technique of creating pattern and design by scratching through a layer of white slip over a red clay body. Typical seventeenth-century North Devon patterns are floral and geometric designs, although stylized birds and other natural motifs are seen often as well. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Erickson at work on the VANITAS jug in the clay studio of the Bideford Art Center, Devon, England, in 2013. (Photo, Robert Hunter.)

A detail of the jug illustrated in fig. 10 showing the fully incised image of artist Grayson Perry.

A photographic collage of some of the source material used to design VANITAS, the Grayson Perry tribute jug. These images were culled from internet sources and adapted by Erickson for the jug’s sgrafitto elements. (Photo, Robert Hunter.)

Michelle Erickson, DON’T TREAD ON ME, Star, North Carolina, 2016. Wood-fired stoneware. H. 16". (Photo, Robert Hunter.) This large jug features the coiled snake of the so-called Gadsden flag of South Carolina, designed during the American Revolution. Thrown with indigenous clays and decorated with porcelain skin-tone slips. Fired in collaboration with David Steumpfle of Seagrove, North Carolina.

Michelle Erickson applies the facial elements of the oversize face jug at the Orzo Studio in Portsmouth, Virginia. (Photo, Robert Hunter.)

Imprinting the face jug with variously colored skin-tone slips at the Visual Arts Center in Richmond, Virginia. (Photo, Michelle Erickson.)

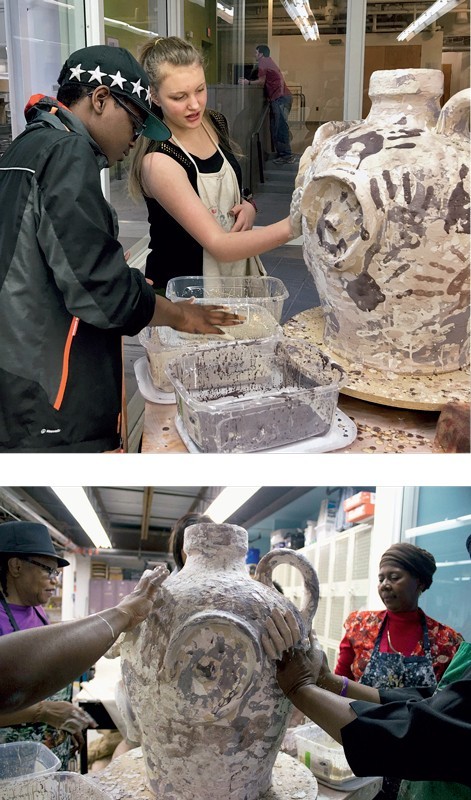

Various community groups were invited to participate in the process of layering hundreds of handprints on the face jug at the Visual Arts Center in Richmond, Virginia. (Photos, Milk River Arts and Mallory Ash Bracken.)

Michelle Erickson, FACE JUG, Portsmouth and Richmond, Virginia, 2016. Wood-fired stoneware. H. 27". (Photos, Jason Dowdle.) Front and side views. Hand‑built with indigenous clay and decorated in porcelain skin-tone slips; fired in collaboration with David Steumpfle.

The reverse of the jug illustrated in fig. 16, showing the inscription “You and I are EARTH” (Photo, Jason Dowdle.)

Salting the groundhog kiln at the North Carolina Pottery Center, 2016. (Photo, Robert Hunter.) In this image, the kiln has reached its highest temperature at 2400°F. Salt is introduced into the kiln at this temperature to create the glaze; the white cloud is the result of vaporization.

Unloading the glazed wares from the cooled kiln. (Photo, Robert Hunter.)

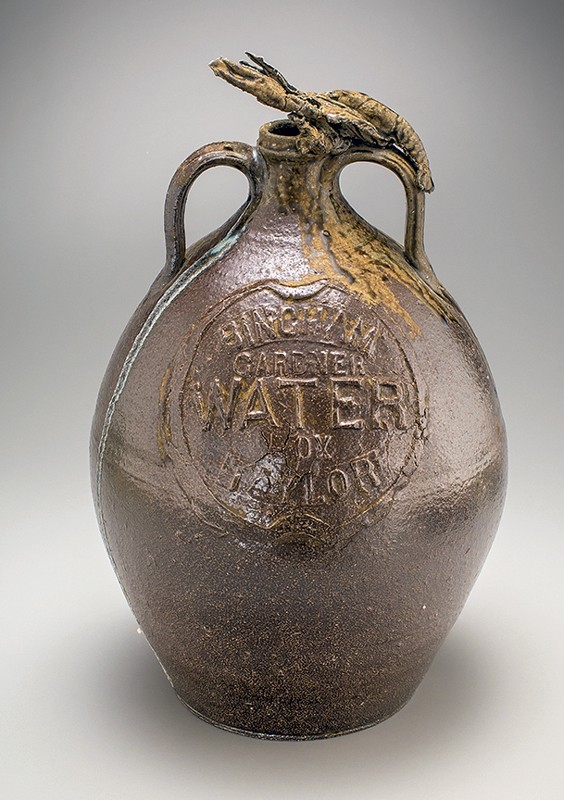

Michelle Erickson, Crawfish Jug, Star, North Carolina, 2016. Wood‑fired salt-glazed stoneware. H. 14". (Artist’s collection; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Michelle Erickson, Lobster Jug, Star, North Carolina, 2016. Wood-fired salt-glazed stoneware. H. 12". (Artist’s collection; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Michelle Erickson, HB2 Ring Bottle, Star, North Carolina, 2016. Wood-fired salt-glazed stoneware. H. 16". (Artist’s collection; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Squirrel bottles, Salem Pottery, Salem, North Carolina, ca. 1805–1820. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 8 1/4". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museum and Gardens; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Michelle Erickson, HB2 Squirrels, Star, North Carolina, 2016. Wood-fired stoneware. H. 24". (Courtesy, Mint Museum Collection, museum purchase funds provided by the Charles W. Beam Accessions Endowment 2019.3a-b; photo, Robert Hunter.) Thrown and hand built with black and white porcelain slip. Fired in collaboration with Ben Owen III, Seagrove, North Carolina.

Michelle erickson is internationally recognized for her mastery of colonial-era ceramic techniques used in her creation of twenty-first-century social, political, and environmental narratives. As a ceramic artist, she transcends the past and present with an unparalleled understanding of period ceramic technology gained through years of observation and experimentation.

Working in historic Tidewater, Virginia, for more than thirty years, Erickson has intensively studied the technology and history behind the ceramics used by the American colonists in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Her efforts have rewarded her with a toolkit of technical skills representing three hundred years of potting traditions and a loyal following of ceramic collectors familiar with Anglo-American decorative arts. She is a proficient chemist, working in a wide range of earthenware, stoneware, and porcelain bodies and glazes, and has successfully applied these skills to her diverse contemporary work. She has set the standard for the current fashionable use of historical references in the field of ceramic arts.[1]

Erickson’s highly sought creations have reinvigorated distinguished decorative arts collections by connecting past and present. Her pieces have been the first contemporary ceramic art acquired by the Colonial Williams-burg Foundation, the New-York Historical Society, the Chipstone Foundation in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, and others. Examples of her work are included in the collections of major museums in America and Britain that include the Museum of Arts and Design (New York), the Seattle Art Museum, the Potteries Museum & Art Gallery (Stoke-on-Trent), and the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A).[2]

Erickson has contributed significantly to many important articles and video presentations of historic ceramic technology, many of which have appeared in Ceramics in America since its inception in 2001.[3] Michelle was artist in residence at the V&A in the category of World Class Maker in 2012. During her tenure, she created three films on her work in the rediscovery of British ceramic techniques in collaboration with the V&A and the Chipstone Foundation.[4]

Her inclusion in “The Last Drop: Intoxicating Pottery, Past and -Present” was a natural extension of her previous work around the topic of alcohol consumption and historical ceramic drinking vessels. One of her earlier works set the tone for the overall project, a sculptural rendition of William Hogarth’s iconic Midnight Modern Conversation in a creamware tableau (figs. 1-3). While this large, fragile sculpture did not travel to “The Last Drop” exhibition, an oversize photograph of it served as backdrop for the space. The inclusion of another of her older works, a reproduction of an eighteenth-century English delft puzzle jug decorated with Van Gogh’s Skull of a Skeleton with Burning Cigarette, added a further allusion to the theme of the inherent dangers of imbibing (figs. 4, 5).

Another of Erickson’s alcohol-related objects was made in 2013 while she was guest artist at the North Devon Festival of Pottery in Bideford, England; it was featured to exemplify how the study of the past informs much of her work. VANITAS is a large harvest jug made in the shape and form of those made by Devon potters in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries (fig. 6, 7). This work in particular illustrates the inspirations gained from Erickson’s firsthand explorations of seventeenth-century North Devon sgraffito found in archaeological excavations in Jamestown, Virginia (figs. 8, 9).

Erickson had described using the communal form and commemorative tradition of North Devon harvest jugs as a potential project during her tenure as artist in residence at the V&A Museum in 2012. The idea came into full realization in September 2013 during the symposium “A New England Cargo” in Bideford. Using the famed North Devon indigenous Fremington clay, she developed a traditional harvest jug form, synthesizing the wealth of the area’s historical, traditional, and studio pottery (fig. 10). The jug’s overarching narrative was a tribute to contemporary British potter Grayson Perry, whose own works are an amalgamation of British pottery traditions and contemporary social and political commentary (fig. 11).

VANITAS perfectly illustrates how Erickson’s work often balances the information age and preindustrial pot making. Working in the Bideford Art Center, she gathered images of Grayson Perry and his artworks, paintings of Queen Elizabeth I, and photographs of Sarah Bernhardt as Hamlet—and Erickson discovered that Bernhardt as Hamlet is, ironically, a dead ringer for Perry’s female persona (fig. 12). Erickson adapted these designs, used in Elizabethan and Georgian archetypes, to create a fictitious coat of arms and emblems made up of Perry’s own works, among them the famed Alan Measles, Grayson’s childhood teddy bear. On the reverse she commemorated the highly celebrated birth of the son of the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge—Prince George, affectionately referred to as “Baby G”—with the prince’s imagined coat of arms. A cherubic Saint George and the dragon at the center of British Petroleum’s helio logo is flanked by the lion and dragon Erickson resurrects from Elizabeth I’s reign.

Working with local clays and materials in the historic potting community of North Devon served as a catalyst for Erickson to explore similar opportunities in her own backyard. She has sought out sources of local wild clays, sometimes stopping to grab clay from roadside utility or construction excavations where promising veins of clay are exposed. Although the kilns in her own studio are electric, she has participated in wood firings in both Virginia and North Carolina. Her DON’T TREAD ON ME jug illustrated in figure 13 is a traditional Southern pottery form, providing the perfect canvas for her political reference to the so-called Gadsden flag of South Carolina, designed by Christopher Gadsden in 1775 during the American Revolution. This particular jug was fired in Seagrove, North Carolina, in the kiln of David Steumpfle.

One of the icons of Southern folk pottery is the “face jug,” a term used generically to reference pottery jugs with applied faces, notably with white kaolin eyes and teeth. Erickson’s FACE JUG was inspired by a specific group of nineteenth-century pottery jugs made by slaves in Edgefield, South Carolina. The purpose of these mysterious, powerful, and intimately sized jugs is still unknown. Their small scale suggests a personal use, perhaps associated with conjuring and African ritual practices. The alkaline-glaze techniques that are characteristic of Southern stoneware production are closely tied to Asian potting traditions rather than the European traditions that dominated the early American salt-glazed stoneware of the mid-Atlantic and North.

The project began with Erickson creating a giant face jug during a workshop with North Carolina–based master potter David Steumpfle at Orzo Studio in Portsmouth, Virginia (fig. 14). She then transported the unfired jug to Richmond, Virginia, to become the centerpiece for her artist residency at the Visual Arts Center there in the spring of 2016. She describes her goal in this exercise: “I wanted to take advantage of the incredible outreach and patronage of this vital inner-city art center to develop a communal project focusing on race in twenty-first-century America. The diversity within the Visual Arts Center was a perfect fit, as people from all walks of life and experience come to create art for many different reasons. Veterans groups, disabled artists, summer students, inner-city youth, and professional retirees who came through the doors brought many hearts, minds, and hands to the project.”

Erickson had been working with commercial porcelain slips produced for the china-doll industry to imitate the skin tones of various races. Those colored slips became a vehicle for Erickson to explore the issue of skin color and race within the community. The skin-tone slips—with names like creole, very white, cameroon, desert beige, and more—were laid out in tubs. People immersed their hands into the tubs and then created their handprints on the jug (fig. 15, 16). This process built up layers of hundreds of handprints, creating a thick, crusty surface of human interaction.

The jug was driven to Seagrove to be fired in David Steumpfle’s wood-fire kiln (figs. 17, 18). The kiln was fired for five days, reaching a temperature of over 2400°F, with continuous stoking by David, Michelle, and the other artists who worked as crew and took eight-hour shifts. The kiln was left to cool for another week. Although the face jug is relatively large for the type, it was dwarfed by the many much bigger pots in the firing and was affectionately named Junior.

“The Last Drop” project also served as a more recent opportunity for Erickson to explore North Carolina historical materials and to participate in the traditions of wood firing. During the summer of 2016, while artist in residence at the nearby STARworks Center for Creative Enterprise, in Star, North Carolina, she produced a body of work that was fired in the salt-glaze stoneware kiln at the North Carolina Pottery Center (fig. 19). Taking advantage of the resources of STARworks’ considerable assortment of indigenous clays, she focused on Catawba Valley clay straight out of the ground to experiment with jug forms. The chance to produce and wood-fire salt-glaze stoneware in a traditional North Carolina groundhog kiln was made possible through the help and expertise of generational North Carolina potter Chad Brown and wood-fire artist David Steumpfle (fig. 20).

Many of the works included here were inspired by the exploration of the impervious material of salt-glazed stoneware. They continued Erickson’s well-known use of historical references to produce a series of jugs that call attention to and add to the protest against world injustices. The devastating water contamination in Flint, Michigan, brought national attention to the disproportionate hidden threats that lower-income and predominantly black populations in the United States face every day, while the industrial use of Native lands threatens not only sacred cultural practices but a very way of life. The jug series Erickson created during her time at STARworks incorporates life-cast shells, octopuses, crayfish and lobster claws, and casts of water and gas mains made from clay impressions taken off the streets in Richmond, Virginia (figs. 21, 22). The Catawba Valley clay and salt-glaze wood-firing mimic industrial salt-glaze water and sewer pipes.

Other works from her STARworks residency were influenced by the political environment during the summer of 2016, specifically the injustice of the Public Facilities Privacy & Security Act (commonly known as House Bill 2, or HB2), a North Carolina statute that required transgender citizens to use public restrooms that correspond to their birth gender; it passed in March 2016. The HB2 Ring Bottle illustrated in figure 23 is one such commentary on gender identity and equality as a human rights issue.

The heightened political environment in North Carolina during the period of debate around the introduction of HB2 inspired a monumental work that drew inspiration from the curious animal-figure icons of -American ceramic history made by the North Carolina Moravian potters in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries (fig. 24). During research at Old Salem, Inc., Erickson had previously studied the original technologies used to make these somewhat mysterious press-molded figural flasks. With knowledge of their original construction and historical context within the North Carolina Moravian community, Erickson began to create larger-than-life, salt-glazed stoneware versions. She titled these monumental creations simply HB2 Squirrels (fig. 25).

Made from North Carolina clays, she placed in their paws the standard gender symbols, Mars for male and Venus for female. Subsequently the figures were coated in black and white porcelain slips and “rainbow flag” graffiti to further signify the issues of discrimination and the struggle for equality. The androgynous nature of the squirrels, the gender symbols they carry, and the use of black, white, and murky rainbow-colored slips mock the requirement of racial, cultural, and gender identity as a valid premise for discriminatory laws and social injustice. On the opposing side the squirrels seem to bleed red, white, and blue from their hands grasping the gender symbols, acknowledging that those willing to make the ultimate sacrifice as American citizens are still not equal under the law.

Michelle Erickson has a BFA from the College of William & Mary and is an independent ceramic artist and scholar. “I make objects of the past from an imagined future in the present.”

Glenn Adamson, “Michelle Erickson,” American Craft (August/September) 2002: 56–59.Robert Hunter, “Making History,” Ceramic Review 200 (March/April 2003): 36–40; -Robert Hunter, “Specializing in the Diverse: The Many Styles of Michelle Erickson,” Kerameiki Techni 47 (July 2004): 43–47; Glen R. Brown, “Michelle Erickson: Projecting a Hypothetical Future, Reflecting on a Problematic Past,” Ceramics Monthly (April 2017): 36–39.

Erickson’s career résumé can be found at www.michelleericksonceramics.com/?action=main (accessed February 9, 2019).

Michelle Erickson and Robert Hunter, “Dots, Dashes, and Squiggles: Early English Slipware Technology,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2001), pp. 94–114; Michelle Erickson and Robert Hunter, “Swirls and Whirls: English Agateware Technology,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2003), pp. 87–110; Michelle Erickson and Robert Hunter, “Making a Bonnin and Morris Pickle Stand,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Easthampton, Mass.: Antique Collectors’ Club for the Chipstone Foundation, 2007), pp. 141–64; Michelle Erickson and Robert Hunter, “Making a Moravian Squirrel Bottle,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter and Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2010), pp. 200–216; Robert Hunter and Michelle Erickson, “Making a Moravian Faience Ring Bottle,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter and Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2010), pp. 190–99.

“How Was It Made? An Agate Teapot by Michelle Erickson,” www.youtube.com/watch?v=

A6QZRFs76Yk (accessed February 9, 2019); “How Was It Made? A Puzzle Jug by Michelle Erickson,” www.youtube.com/watch?v=s7gXmra-i7M&t=16s (accessed February 9, 2019); “Michelle Erickson and London’s Indigenous Clay,” www.youtube.com/watch?v=lkigLI7eX9o (accessed February 9, 2019).