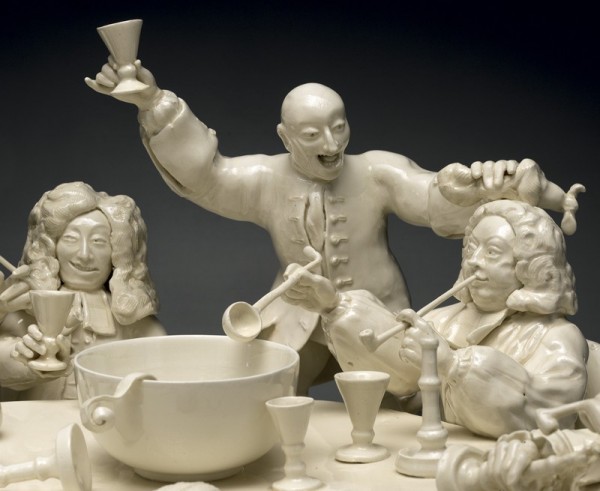

Detail of the figural group illustrated in fig. 3. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

William Hogarth, A Midnight Modern Conversation, London, England, 1733. Etching and engraving on laid paper. 15 1/16 x 20 1/2". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

Michelle Erickson, A Midnight Modern Conversation, Hampton, Virginia, 1999. Modeled and thrown creamware. W. 26". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Michelle Erickson, Van Gogh Puzzle Jug, V&A Residency, London, 2012. Tin-enameled stoneware. H. 10". (Collection of the artist; photo, Robert Hunter.)

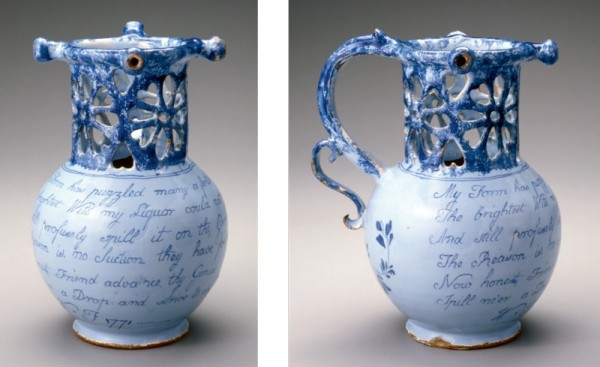

Puzzle jug, Bristol, England, dated 1771. Tin-enameled earthenware. H. 8 1/2". (Chipstone Foundation.) The jug is thrown and has at the rim a three‑nozzled tube connected to a hollow handle with an S-scroll at the base. The neck piercings include four flowers separated by pairs of hearts. The bottom is unglazed. Sponging decorates the neck, nozzled rim, handle, and S-scroll. Painted decoration includes a peony and a rhyme:

My Form has puzzled many a fertile Brain.

The brightest Wits my Liquor could not gain

And Still profusely spill it on the Ground

The Reason is, no Suction they have found

Now honest Friend advance, thy Genius try

Spill ne’er a Drop and strive to dr[ink] me dry

W [star] F 1771

Michelle Erickson, VANITAS, Bideford, Devon, England, 2013–2015. Sgraffito-decorated wood-fired slipware. H. 17". (Courtesy, William C. and Susan S. Mariner Collection; photo, Robert Hunter.) The jug was made with indigenous North Devon “Fremington” clay and North Devon ball clay slip. It was fired in Clive Bowen’s St. Ives Studio, Cornwall, England.

Side views of the jug illustrated in fig. 6.

Dish, North Devon, England, ca. 1670. Slipware. D. 12 1/8". (Courtesy, Collection of Colonial National Park, National Park Service; photo, Ceramics in America.) One of many nearly intact examples of North Devon sgraffito slipware recovered from archaeological excavations.

Erickson demonstrates the sgraffito technique of creating pattern and design by scratching through a layer of white slip over a red clay body. Typical seventeenth-century North Devon patterns are floral and geometric designs, although stylized birds and other natural motifs are seen often as well. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Erickson at work on the VANITAS jug in the clay studio of the Bideford Art Center, Devon, England, in 2013. (Photo, Robert Hunter.)

A detail of the jug illustrated in fig. 10 showing the fully incised image of artist Grayson Perry.

A photographic collage of some of the source material used to design VANITAS, the Grayson Perry tribute jug. These images were culled from internet sources and adapted by Erickson for the jug’s sgrafitto elements. (Photo, Robert Hunter.)

Michelle Erickson, DON’T TREAD ON ME, Star, North Carolina, 2016. Wood-fired stoneware. H. 16". (Photo, Robert Hunter.) This large jug features the coiled snake of the so-called Gadsden flag of South Carolina, designed during the American Revolution. Thrown with indigenous clays and decorated with porcelain skin-tone slips. Fired in collaboration with David Steumpfle of Seagrove, North Carolina.

Michelle Erickson applies the facial elements of the oversize face jug at the Orzo Studio in Portsmouth, Virginia. (Photo, Robert Hunter.)

Imprinting the face jug with variously colored skin-tone slips at the Visual Arts Center in Richmond, Virginia. (Photo, Michelle Erickson.)

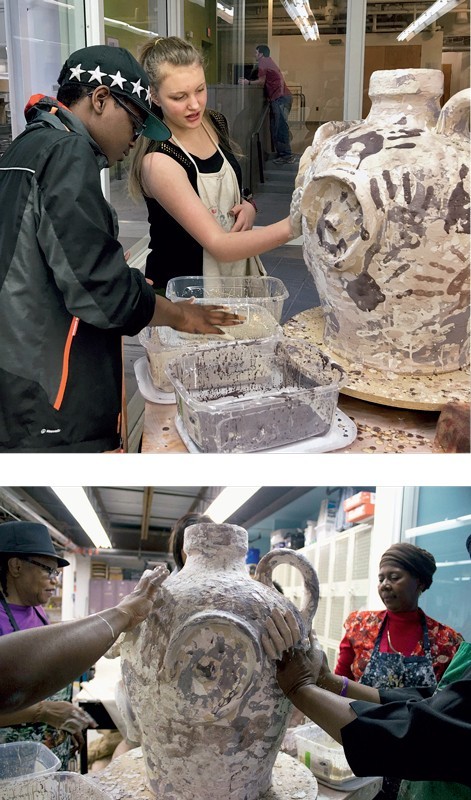

Various community groups were invited to participate in the process of layering hundreds of handprints on the face jug at the Visual Arts Center in Richmond, Virginia. (Photos, Milk River Arts and Mallory Ash Bracken.)

Michelle Erickson, FACE JUG, Portsmouth and Richmond, Virginia, 2016. Wood-fired stoneware. H. 27". (Photos, Jason Dowdle.) Front and side views. Hand‑built with indigenous clay and decorated in porcelain skin-tone slips; fired in collaboration with David Steumpfle.

The reverse of the jug illustrated in fig. 16, showing the inscription “You and I are EARTH” (Photo, Jason Dowdle.)

Salting the groundhog kiln at the North Carolina Pottery Center, 2016. (Photo, Robert Hunter.) In this image, the kiln has reached its highest temperature at 2400°F. Salt is introduced into the kiln at this temperature to create the glaze; the white cloud is the result of vaporization.

Unloading the glazed wares from the cooled kiln. (Photo, Robert Hunter.)

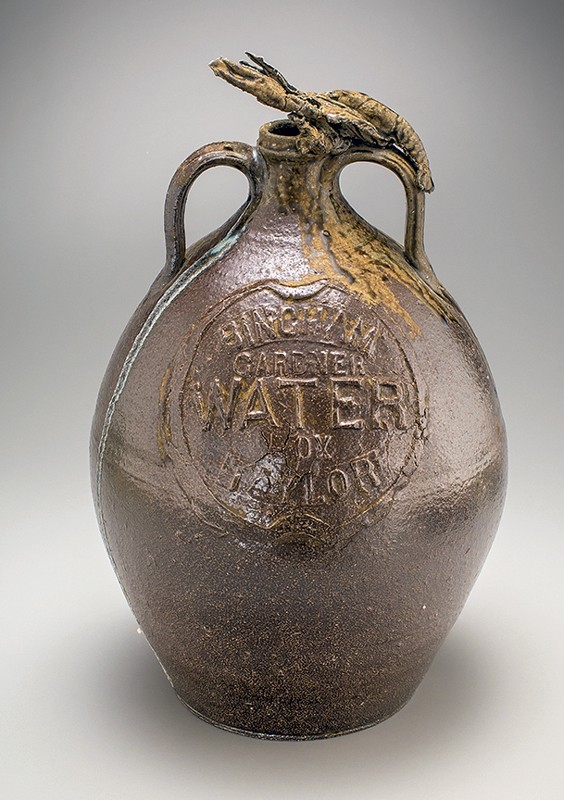

Michelle Erickson, Crawfish Jug, Star, North Carolina, 2016. Wood‑fired salt-glazed stoneware. H. 14". (Artist’s collection; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Michelle Erickson, Lobster Jug, Star, North Carolina, 2016. Wood-fired salt-glazed stoneware. H. 12". (Artist’s collection; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Michelle Erickson, HB2 Ring Bottle, Star, North Carolina, 2016. Wood-fired salt-glazed stoneware. H. 16". (Artist’s collection; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Squirrel bottles, Salem Pottery, Salem, North Carolina, ca. 1805–1820. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 8 1/4". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museum and Gardens; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Michelle Erickson, HB2 Squirrels, Star, North Carolina, 2016. Wood-fired stoneware. H. 24". (Courtesy, Mint Museum Collection, museum purchase funds provided by the Charles W. Beam Accessions Endowment 2019.3a-b; photo, Robert Hunter.) Thrown and hand built with black and white porcelain slip. Fired in collaboration with Ben Owen III, Seagrove, North Carolina.