The wood-firing pottery kiln of Greg Shooner and Mary Spellmire-Shooner, Oregonia, Ohio, December 3, 2015. (Photo, Brenda Hornsby Heindl.)

Greg Shooner stoking the firebox of his wood-firing kiln, December 3, 2015. (Photo, Rob Manko.)

Jar, Greg Shooner, Oregonia, Ohio, 2015. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 7 1/2". (Photo, Rob Manko.)

A collection of pottery made by Greg Shooner in front of the firebox of his wood-firing kiln, December 3, 2015. (Photo, Rob Manko.)

Dish, attributed to Henry Troxel, Upper Hanover Township, Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, 1828. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 10 1/4". (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art.)

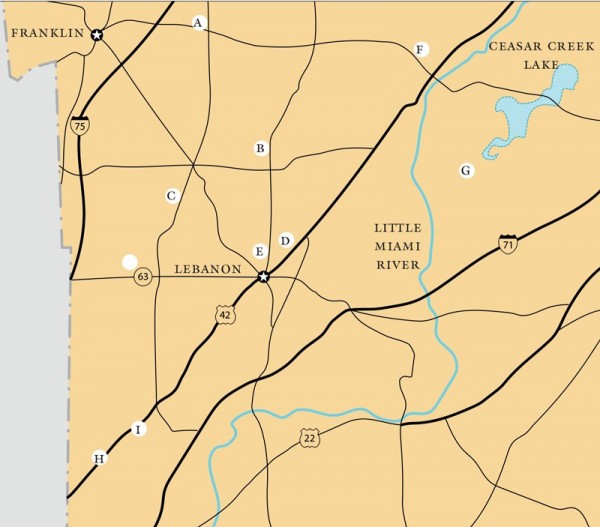

Map showing the location of potters working in Warren County, Ohio, in the nineteenth century.

A. Joseph Walters, 1840–1860

B. Merritt/Gray, 1810–1860

C. Shaker, 1860–1851

D. Wm. Jackson,Wm. Shugert,

John Foglesong, 1835–1884

E. George Foglesong, 1810–1831

F. Thomas Swift, 1808–1836

G. Elisha Vance, 1828

H. Silas Ballard 1859–1879

I. Wm. Jared, 1848–1883

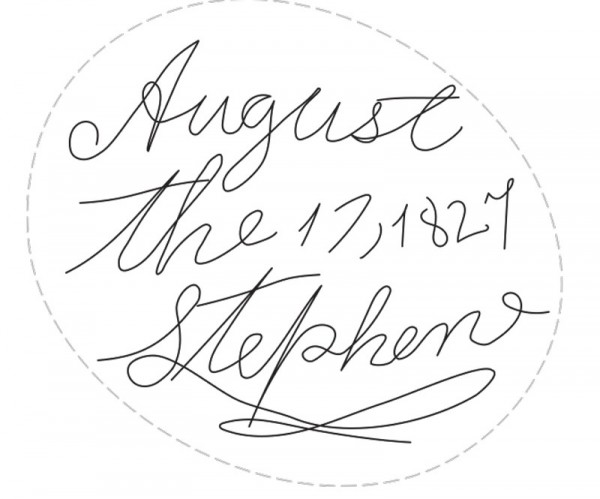

Jar, attributed to Stephen Easton, Union Village Shaker community, Warren County, Ohio, 1827. Lead-glazed earthenware. Mark (incised on base): August / the 17, 1827 / Stephen (Photo, Greg Shooner.)

Illustration of the inscription on the base of the jar illustrated in fig. 7.

Aerial view of excavation on the North Family Lot, Union Village Shaker community, Warren County, Ohio, 2005. (Courtesy, Ohio Department of Transportation.)

Nineteenth-century pipe heads excavated at the North Family Lot, Union Village Shaker community, Warren County, Ohio, 1804–1852. (Courtesy, Ohio Department of Transportation.)

Raw clay before it is processed in the pug mill. (Photo, Greg Shooner.)

Raw clay before it is put into the pug mill, showing the distinct color variations that will blend in the pug mill. (Photo, Greg Shooner.)

Dish, Mary Spellmire-Shooner, Oregonia, Ohio, 2015. Lead-glazed earthenware with slip-painted decoration. D. 8". (Photo, Rob Manko.)

Detail of the slip-painted decoration on the dish illustrated in fig. 13.

Jar, Greg Shooner, Oregonia, Ohio, 2015. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 6". (Photo, Rob Manko.) Note that the white slip-trailing under the lead glaze, made using an iron-rich clay, gives the white slip a yellow appearance.

Jug, Greg Shooner, Oregonia, Ohio, 2015. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 8". (Photo, Rob Manko.)

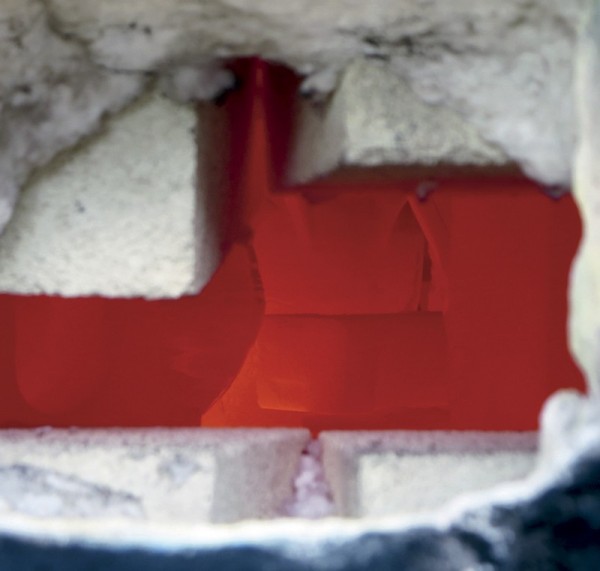

Firebox for the Shooners’ wood-firing kiln showing the deep red color that appears during reduction. (Photo, Brenda Hornsby Heindl.)

Flames coming through the ceiling of the wood-firing kiln and black smoke showing signs of reduction. (Photo, Brenda Hornsby Heindl.)

Showing the bright interior of the kiln and the visible sheen as the glaze fluxes during reduction. (Photo, Brenda Hornsby Heindl.)

Jar, New Market, Shenandoah Valley, Virginia, 1860–1880. Lead‑glazed earthenware. H. 7 1/2". (Courtesy, Jeffrey S. Evans & Associates Auctions, June 17, 2017, sale lot #1016; photo, Will McGuffin.)

Close-up of the jar illustrated in fig. 20, showing several places where organic material had burned out and left a small hole for oxygen to create a halo.

Jar, attributed to Galena, Illinois, 1860–1880. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 8 5/8". (Courtesy, Jeffrey S. Evans & Associates Auctions; photo, Will McGuffin.)

Close-up of the base of the jar illustrated in fig. 22. Leaving the base unglazed allowed the glaze to oxidize around the base of exposed clay, creating a ring of yellow-orange color.

Jar, Greg Shooner, Oregonia, Ohio, 2015. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 10". (Photo, Rob Manko.)

Close-up of one of Greg Shooner’s pieces on which a halo has formed. Note the pinhead hole at the center where the oxygen entered beneath the glazed surface. (Photo, Rob Manko.)

Left to right: Mary-Spellmire Shooner, Dorothy Auman, and Walter Auman, Seagrove, North Carolina, ca. 1986. (Photo, Greg Shooner.)

Pottery stacked in the Shooner kiln, ready for firing, December 3, 2015. (Photo, Brenda Hornsby Heindl.)

Extruded rail-style kiln furniture from the pottery site of Jacob Meddinger, Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1920. (Private collection; photo, Rob Manko.)

Dish resting on rail-style kiln furniture. (Photo, Rob Manko.)

Dishes with coggled rims sitting on rail-style kiln furniture leaning against one another prior to firing. (Photo, Greg Shooner.)

Back edge of dishes that were leaning against one another during firing; the small marks show where the coggled edge made contact with another piece. (Photo, Greg Shooner.)

Coggling the edge of a dish. (Photo, Greg Shooner.)

Dish, Henry Roudebusch, Upper Hanover Township, Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, 1816. Lead‑glazed earthenware. D. 11 7/8". (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art.) The downward flow of the green copper oxides indicates that the dish was standing upright in the kiln during firing.

Pottery unloaded after the 2015 lead-glazed wood-fired kiln firing in the Shooner pottery shop. (Photo, Brenda Hornsby Heindl.)

“This is as real as it gets,” Greg Shooner said as flames shot through the vent holes in the roof of his wood-firing kiln and acrid black smoke surrounded it (fig. 1). Greg and Brenda Hornsby Heindl, both potters, were working around the fireboxes of the kiln, filling them with wood, making heavy stokes, throwing the kiln into reduction and creating the blackened smoke (fig. 2). Greg was working toward what many traditional potters would have considered undesirable: a rich green color with halos of orange throughout surface of the vessel (fig. 3). As Greg had come to understand, the only way to truly achieve what historical potters had was to use the same wood-firing kiln with wild, non-commercial clays and a lead glaze. This article explores one potter’s passion for American lead-glazed earthenware, and the chemistry underlying the often misinterpreted surface appearance of the venerated antique lead-glazed earthenwares found in museums and private collections (fig. 4).

Inspiration from the Past

Greg Shooner and his wife, Mary Spellmire-Shooner, developed an interest in the history of red earthenware following the excitement of the 1976 Bicentennial and the newfound enthusiasm for America’s material past. They subsequently began working in a pottery shop owned by traditional cabinetmaker David T. Smith in southern Ohio, where they producedred earthenware using a commercial, clear, non-lead glaze. Their pottery was inspired by slip-decorated earthenware in the Pennsylvania German collection at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, although at the time their closest access to those objects was through the black-and-white images in curator Bea Garvan’s catalog.[1] The catalog described the pieces as having white slip with some green or manganese decoration, but it was impossible for Greg and Mary to fully interpret the objects from the black-and-white photos. They finally visited the Pennsylvania German collection in 1985 and were astounded by what they saw. Though the forms and decorations were familiar, the use of color and the yellow appearance of the white slip beneath the lead glaze was unlike anything they had ever seen (fig. 5).

Having witnessed firsthand the nuances of lead glaze, Greg and Mary began to develop the idea of reproducing American lead-glazed red earthenware using a true lead glaze. After several years of experiments using non-lead formulas that failed to re-create the appearance of period lead-glazed surfaces, they mixed a glaze using lead oxide, or red lead. Upon firing several test pieces, it was clear there would be no going back to a lead-free glaze. As many modern craftsman have learned, the only way to re-create the past is to use the same materials and methods that potters had used for centuries. At this juncture the couple decided their work would be invested in the accurate interpretation of early ceramics rather than in the creation of a functional line of modern ware. They built their own pottery shop in 1993, and a year later added a wood-firing kiln to their operation.

Through his experimentation and ultimate success in refining the use of a lead glaze combined with the re-creation of historical forms and decorative techniques, Greg became a recognized expert in the art and history of ceramic production, particularly in southeastern Pennsylvania, leading to an invitation in 2006 to join a panel sponsored by the Philadelphia Museum of Art to reassess its Pennsylvania German collection. As a member of the panel, Greg was able to immerse himself fully in this seminal collection, and closely study each piece of pottery. He once again returned to Ohio full of passion for the beauty and endless variety of effects produced by lead glaze.

Local Earthenware Production

Although they were inspired by Pennsylvania German earthenware, Greg and Mary in fact lived in Warren County, Ohio, whose historical pottery and potters certainly influenced their own work. An abundance of earthen-ware clay provided the impetus for many potters to settle in the region in the late eighteenth century, and Warren County, located between Cincinnati and Dayton, was a hub of economic prosperity in the first quarter of the nineteenth century.

Greg has identified many of those original potters working in Warren County, among them Elisha Vance in Greg’s hometown of Oregonia, Ohio, as early as 1818 (fig. 6). Settled by families from various ethnic backgrounds coming largely from Connecticut, New Jersey, New York, and -Pennsylvania, several religious groups also settled in the county, including the communal Quakers and Shakers, who produced crafts and other goods to support their communities. Union Village, the only known Shaker community toproduce lead-glazed earthenware in the early nineteenth century, is located in Warren County. The Union Village Shakers produced a wide range of functional earthenware forms, beginning in 1804 with smoking pipes and pieces embellished with polychrome slip-trailed decoration (figs. 7, 8). In 2005 the pottery site at Union Village was partially excavated as a part of a road-expansion project (fig. 9). Greg consulted with the archaeological firm responsible for excavating the site, and helped to curate the collection. This ultimately led to the creation and subsequent installation of an award-winning exhibit at the Warren County Historical Society in Lebanon, Ohio (fig. 10).[2]

Making and Decorating

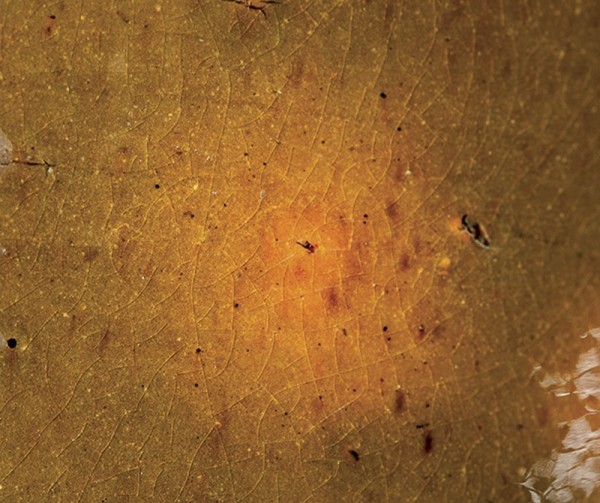

The wild clay used by Greg and Mary comes from central Pennsylvania, near Harrisonville. It is dug by hand and processed through a quarter-inch wire-mesh screen to remove larger stones, before being pugged in a mechanical pug mill (figs. 11, 12).[3] A pug mill is used to mix and compress clay to a uniform consistency for use on a pottery wheel. The clay is a light tan color when raw, but iron in the body oxidizes during the early stages of firing and forms iron oxide, which gives all red earthenware its rust-red color. Some earthenware clays local to Warren County are blue-gray when dug, but because they contain iron they will fire to a red color. Also present in the raw clay are organic particles—leaves and roots, for example—which burn out between 250 and 480 degrees Celsius (450–900°F). These play a role in the “halos” of orange that are discussed later.

The Shooners’ influences, like those of many early American potters, are not only German, but also Dutch, Hungarian, Swiss, and Ukrainian, among others. Tulips, deer, birds, and assorted other motifs used in these European traditions are instantly recognizable to any student of southeastern Pennsylvania handcrafts, especially sgraffito and slip-decorated earthenware vessels. Sgraffito refers to a decoration having a pattern cut through the applied layer of slip to expose the red clay body beneath, with no added color other than the occasional splashing of a copper green, randomly or specifically, over the design. Many southeastern Pennsylvania pieces are decorated in this way. The use of slip to embellish pottery is commonly referred to as an underglaze decoration, that is, colors applied to the clay body beneath a clear glaze. A “slip” is simply clay that is ground and mixed with water to the consistency of heavy cream; often it is colored with various metallic oxides. A dark-brown slip is the result of mixing iron or manganese with a red clay; adding copper to a white clay yields an attractive green. “Slip trailing” refers to an application method that many consider to be similar to decorating a cake, since the slip is poured directly onto the surface of the ware through a small conduit or pipette—often the hollow base of a goose quill—in spontaneous, creative motifs. Pots can also be entirely covered with a slip coating, either by brushing, dipping, or pouring, to establish an alternate ground for further slip trailing or to provide a base for detailed sgraffito decoration.

The Shooners use a decorating technique called “slip painting,” which refers to coating the piece of pottery with a light slip and cutting a design through the slip with a stylus. The recessed decoration is then infilled with different colors of slip (figs. 13, 14). Of European origin, slip-painted earthen-ware requires more precision than the more traditional, free-flowing slip-decorating techniques.

Understanding Lead Glaze

The earliest use of lead as a glaze material was by the Roman potters in western and southern Asia Minor between 100 B.C. and A.D. 200.[4] The most common form of lead used in traditional glazing is lead oxide or red lead (Pb3O4), but others forms include lead carbonate or white lead (PbCO3) or litharge, a mineral form of lead oxide. Early earthenware potters often found suitable forms of lead in creative and thrifty ways. Lead carbonate was made by putting scrap rolls or shavings of lead into a vinegar bath.[5] The reaction between the lead and acid in the vinegar created a white powder (the lead carbonate) on the lead surface, which eventually precipitated to the bottom of the container.[6] The lead carbonate could be used as is or heated in a pan, which drove off the carbon and ultimately produced red lead oxide.

The differences in appearance between red lead and white lead on finished pots can be subtle or distinctive. Any glaze is essentially a thin film of glass sealing and coating the clay surface. A glaze relies on clay as a binder; the clay also provides silica and alumina, the basic elements of all glass. Lead, which acts as a flux or accelerant to melting, causes clay to melt into a glaze when mixed together. Most potters use the same clay for their pottery and their glaze, which allows the glaze and the clay body to expand and contract at the same rate during firing.[7] The iron in the clay melts into the lead, giving a subtle clear yellow or amber cast to any white slip decorations that might be beneath it (fig. 15). If white lead is added to an iron-free white clay, slip decorations are less affected, providing truer colors from the underlying slip.

Historically, southeastern Pennsylvania’s earthenware production was composed primarily of lead-glazed red earthenware pottery in simple, utilitarian forms. Examples are found in abundance in archaeological collections, particularly in Philadelphia, where lists documenting workshops and factories show hundreds of potters working in the city in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.[8] Utilitarian wares are often overlooked by researchers because of their ubiquity and general lack of decoration, although archaeological examples associated with production sites and later marked pieces have provided distinguishing characteristics that are helpful in making specific attributions.

Prior to the mid-eighteenth-century, many lead glazes were applied in a powdered form, but innovations in England led to the use of liquid glazes in America.[9] It was generally known that there was a certain toxicity associated with lead-glazed vessels—although, contrary to popular belief, the lead in such glazes is not absorbed through one’s skin; it must be ingested or inhaled to be dangerous. As early as 1785 the public was being informed about the use of lead glaze on pottery. The Pennsylvania Mercury noted, “Even when it is firm enough, so as not to scale off, it yet is imperceptibly eaten away by every acid matter; and mixing with the drinks and meats of the people, becomes a slow but sure poison, chiefly affecting the nerves, that enfeebles the constitution, and produces paleness, tremors, gripes, palsies, &c.”[10] Nonetheless, the abundance of locally produced red earthenware showed them to be everyday household vessels in many Pennsylvania homes, even after other, safer wares became available.[11]

Lead glaze imparts a surface quality that has never been replicated by any commercial non-lead glaze. Due to its toxicity when exposed to acids, however, lead-glazed pottery has now been relegated to decorative status: all of the Shooners’ pottery is deeply and prominently stamped: “This glaze contains LEAD, not for food storage or use.” The Shooners are frequently asked if the results are worth the work and effort of glazing and firing in such a special way. Their answer is always a resounding “Yes,” as they continue to preserve a tradition once used across America. The bright, glassy sheen of the glaze, together with the soft, flowing colors of the finished ware, are as mesmerizing as they are captivating (fig. 16).

Understanding the Lead-Glazed Surface

The appearance of lead-glazed pots is often misinterpreted because it is not understood. The olive-green color with orange spots is the result of several factors, including the type of clay that is used and the atmosphere created in the kiln. These colors are not achieved through the use of mottled or colored glazes, nor are they applied. The lead glaze itself is a clear coating, imparting no discernible color of its own, even after it is fired.

During the later stages of firing, as the fireboxes are stoked and begin to attain a bright color, the wood fuel is consumed at an ever increasing rate (fig. 17). As refueling continues, incomplete combustion occurs, producing waves of thick, black smoke (fig. 18). This is not your fragrant campfire smoke, but a pungent cloud of raw carbon that resembles the smell of coal or coke burning. Inside the kiln, this carbon begins to displace the very oxygen the fire is thriving on, but at 850 degrees Celsius (approximately 1500°F) the fire cannot be suffocated. At this point the kiln will begin to send tongues of flame out of any and all peepholes and cracks as the fire searches for any trace of oxygen. This is known as a “reduced” or “reduction” atmosphere. It affects all types of pottery, but its effect on lead-glazed earthenware can be uniquely beautiful or subtle, and as varied as it is unpredictable.

The magic in the kiln happens during the last 200–300 degrees of the firing, when the starved atmosphere ultimately locates oxygen in the iron oxide molecules of the pottery’s clay body. It splits the molecules to consume the oxygen, leaving behind ferric iron, which is naturally a black color. This causes the body of the pot to turn a darker color, and the remaining iron creates a greenish surface on the lead-glazed vessels. A light reduction will result in the palest olive green, but as oxygen continues to be stripped away, the color will darken to a black-green or even jet black.

It is difficult to determine what colors the pots will turn while the kiln is being fired. As the kiln reaches its final temperature, the pottery as well as the entire kiln interior glows a bright yellow, hiding the true colors of both the decorations and the reduction (fig. 19). These changes to the surface appearance of the pottery are not visible until the kiln has been completely cooled and can be unloaded or “drawn.” After the peak temperature is achieved, combustion, or reduction, ceases. During this process, while the kiln is still glowing with heat but beginning to drop in temperature, oxygen re-enters the kiln and the iron seeks to rejoin with the oxygen to restore its natural state of iron oxide. The most distinctive effect occurs when a tiny bit of organic matter in the clay burns away during firing and leaves a small pinhole in the glaze. Oxygen enters this breach, reunites with the iron, and spreads radially to create halos around these areas on the otherwise olive-green surface (figs. 20-24).

In all cases, these color effects and variability occur only on ceramics that have been created through a single firing technique. This is opposed to making and decorating the pottery, then subjecting it to an initial or “bisque” firing, which transforms the raw clay into a hard ceramic surface and facilitates the glazing and loading of the kiln for the final firing, a common procedure historically and used by many potters today. Single firing produces the desired results only when a raw clay body is used, as opposed to a refined, commercially produced clay. The halo effect will not occur on pots that have been bisque fired because the organic materials in the raw clay that play a critical role in producing them would be burned away before the glazed is applied.

The Lead-Glaze Kiln

Realizing the limitations of electric kiln firing, Greg and Mary sought advice on how to construct a wood-firing kiln that could create a reduction atmosphere. While traveling through North Carolina, they visited the late Walter and Dorothy Auman, two nationally recognized potters and historians of traditional pottery, to discuss how best to build a kiln to create this desirable surface (fig. 26). While acknowledging that there was “no specific design to go by,” Walter suggested that they “build a simple one” that very afternoon which emphasized the basic nature of a kiln layout but alluded to the depth of knowledge a potter required about kiln construction and firing techniques. The Shooner’s own kiln, built in 1994, is the culmination of research on how to achieve a green reduced surface on lead-glazed earthenware.

In terms of the kiln’s construction, Greg moved toward a “beehive updraft kiln,” a type often used historically in southeastern Pennsylvania and many other parts of the world. The beehive kiln is shaped like a bee skep, with a circular base and domed top. “Updraft” refers to the direction in which the heat travels from the firebox through the exit flue, upward through the floor, around the pottery, and out of the roof.[12] The circular kiln Shooner built features three fireboxes leading to a 225-cubic-foot interior. The dome roof was cast with 2 1/2-inch vent holes as exit flues to allow air ventilation, as a chimney would on other styles of kiln. In a nod to its post-medieval technology, the exterior was built of stone but was lined with a high-temperature fiber blanket and soft firebrick on the interior. An iron band surrounds the kiln to help contain the expansion or “thrust” of the dome against the exterior wall during firing. When they are being fired, kilns move with subtle expansion and contraction from the heating and cooling of the kiln components. A potter using an updraft kiln of this type must develop a special relationship with it, to know and understand its hot and cold spots because of the inconsistencies of wood-firing and the nature of how heat moves through an updraft kiln, as well as its reaction to windy or inclement days, which of course can impact the draft patterns drawing the heat from the firebox to the roof.

Loading and Firing the Lead-Glaze Kiln

Setting or stacking the kiln begins in the glaze room, where care is taken to prevent glazed surfaces from coming into contact with other pots during the firing (fig. 27). While kiln “furniture” of many shapes and sizes is used, the most common method employs a “dry” rim and/or foot that allows vessels to be stacked atop each other while preventing the pieces from adhering to one another.

Efficiency of space is key to a successful firing. Crocks and jars are glazed with a quick swirl inside followed by a dip in the glaze and wipe of a sponge around the rim. Slab-formed vessels can be brushed or swirled, and are finished on the surface only. In the kiln these are set on a special tile or “rail,” which is an extruded piece of furniture featuring two raised rails on a long slab, much like a train track (fig. 28). The dishes are fired in a vertical position, with one dish leaning against another and the bottom edge in contact with only the two points of the raised rails (figs. 29, 30). This arrangement is often evidenced by a directional flow of glaze colors on the front of the dish.

Coggled rims on earthenware dishes are not simply decorative; they also serve to minimize contact on the back of the vessels (figs. 31, 32). Excess glaze falls from the dish to the rail below, leaving telltale pools on the kiln furniture. Despite the fluidity of the lead glaze (it begins to melt at about 500°C), the coloring oxides used in slip decoration are strong fluxes and increase the melt fluidity of the lead. This phenomenon appears as “runny” areas of color, especially manganese and copper, in the decorations of jars and dishes with an otherwise stable glaze. Often visible on historical vessels by the direction in which the copper green or dark brown manganese colors trail down a plate or dish, this trailing illustrates how the vessel was standing in the kiln (fig. 33).

Conclusion

Two days later, after Brenda and Greg had made the final stoke described in the opening paragraph of this article, the kiln had cooled, and the eighteen-hour firing had produced beautifully reduced wares. Greg and Mary filled the tables in their shop with pots fresh from the kiln (fig. 34) and shining bright in the morning light. The iridescence from the lead in the glaze, and the array of greens, mottled oranges, and reds, were testament to the potters’ respect for and dedication to understanding the subtleties and complexities of the traditional process. It was hard to believe the variety of colors that came from that one kiln firing, as well as the strength of the bright sheen of the lead glaze. Understanding this wide spectrum of colors requires knowledge of the manufacturing process and how materials and methods impact the appearance of the ware. This knowledge helps provide insight into why the surface of an antique vessel that appears to be decorated might actually have been the result of the kiln firing, and the myriad variables over which even the potter rarely has full control.

“As real as it gets,” indeed.

Beatrice B. Garvan, The Pennsylvania German Collection (Philadelphia, Pa.: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1982).

Encountering the Shakers of the North Family Lot, Union Village, Ohio, monograph series vol. 4: Simplicity Comes in All Forms—The Shaker Ceramic Industries of Union Village, by Patrick M. Bennett, Thomas Grooms, Andrew R. Sewell, and Bruce Aument, archaeological report submitted to the Ohio Department of Transportation Office of Environmental Services by Hardline Designs Company, prepared January 30, 2009, www.dot.state.oh.us/Divisions/Planning/Environment/Cultural_Resources/Documents/Volume4.pdf (accessed May 24, 2018).

The process of “pug milling” is mixing clay, usually with a heavy auger machine, which blends the clay into “pug,” meaning the clay is without air bubbles and is smooth and plastic, making it ideal for throwing on the pottery wheel.

Rose Kerr and Nigel Wood, Science and Civilisation in China, Vol. 5, Part 12, Chemistry and Chemical Technology: Ceramic Technology (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), p. 485.

Personal conversations between Greg Shooner and Gene Comstock, ca. 2006.

H. E. Comstock, The Pottery of the Shenandoah Valley Region (Winston-Salem, N.C.: Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts, 1994), p. 52. For the purpose of preparing glaze, the Bell pottery in the Shenandoah Valley is said to have received, by the bushel, lead bullets that had been collected from the field at the battle of Fisher’s Hill in 1864. A. H. Rice and John Baer Stoudt, The Shenandoah Pottery (Strasburg, Va.: Printed by Shenandoah Publishing House, 1929), p. 49.

Comstock, Pottery of the Shenandoah Valley Region, p. 53.

Susan H. Myers, Handcraft to Industry: Philadelphia Ceramics in the First Half of the Nineteenth Century (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1980), pp. 50–90; Arthur E. James, The Potters and Potteries of Chester County, Pennsylvania, 2nd ed. (Exton, Pa.: Schiffer Publishing, 1978), pp. 199–204; Lester P. Breininger, Potters of the Tulpehocken (n.p.: self-published, 1979), pp. 53, 54.

Diana Stradling and J. Garrison Stradling, The Art of the Potter: Redware and Stoneware (New York: Main Street/Universe Books, 1977) [originally appeared in the magazine Antiques].

Pennsylvania Mercury and Universal Advertiser, February 4, 1785.

Meta F. Janowitz, “Decline in the Use and Production of Red-Earthenware Cooking Vessels in the Northeast, 1780–1880,” Northeast Historical Archaeology 42 (2013), https://doi.org/10.22191/neha/vol42/iss1/7 (accessed May 24, 2018).

Brenda Hornsby Heindl, “America’s Historic Kilns: A Potter’s Perspective,” American Ceramic Circle Journal 17 (2013): 125–48.