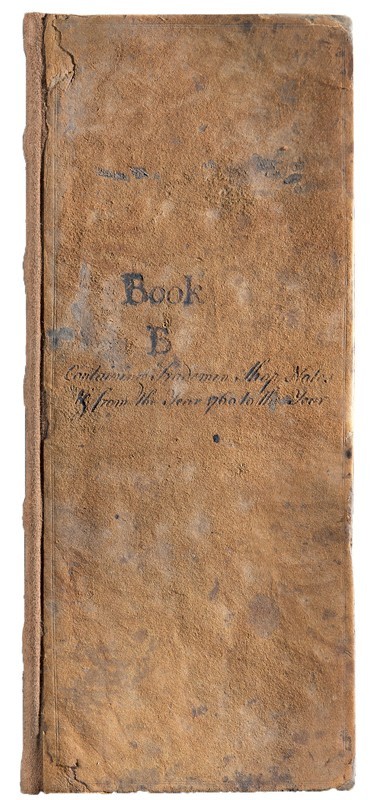

William Fairfax and George William Fairfax Account Book, 1742, 1748, 1760–1772. Account book B kept by George William Fairfax “Containing Tradesmen Shop Notes & c from the Year 1760 to the Year [1772].” (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

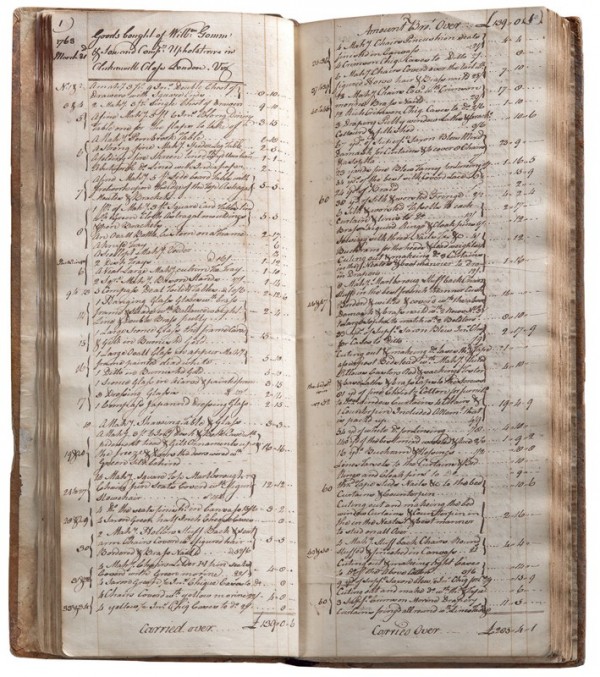

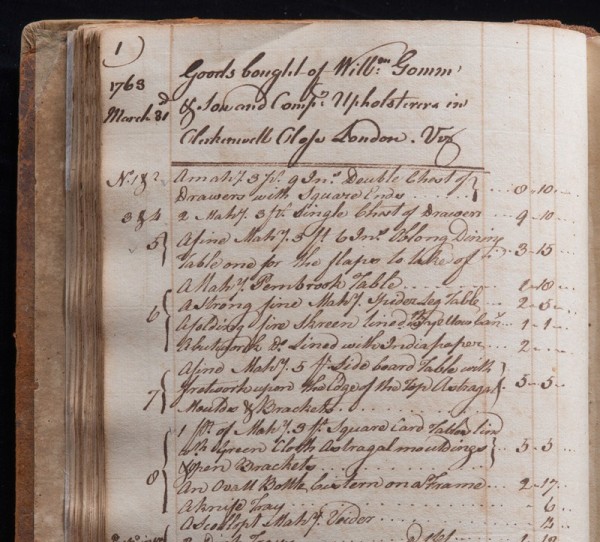

Invoice for furniture and upholstered goods purchased by George William Fairfax from the London firm William Gomm and Son and Company on March 31, 1763, on pp. 1–2 in George William Fairfax’s account book. (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The goods are listed with their prices on the right and the numbers of their shipping crates on the left.

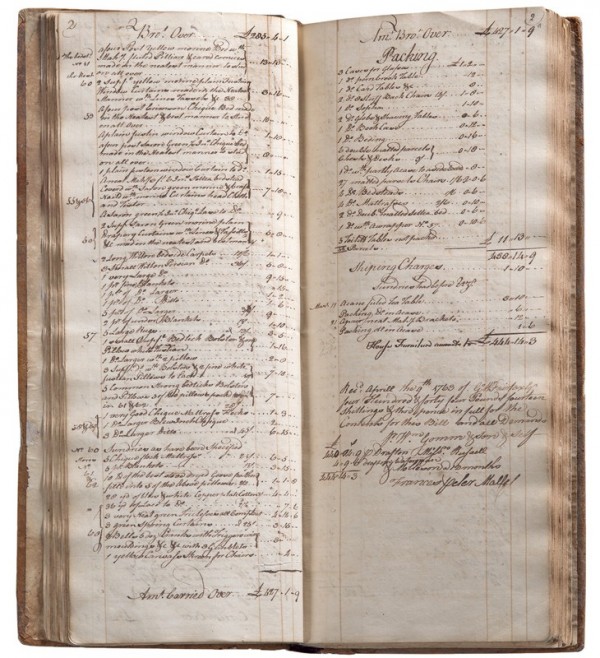

Invoice for furniture and upholstered goods purchased by George William Fairfax from William Gomm and Son and Company on March 31, 1763, on pp. 3–4 in George William Fairfax’s account book. (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Chimney back, Marlboro Furnace, Frederick County, Virginia, ca. 1770. Cast iron. 34 1/2" x 31". (Courtesy, United States Army Engineer Museum, Fort Belvoir, Virginia; photo, Robert Hinds.) Thomas, 6th Lord Fairfax commissioned a set of chimney backs, represented by this example, for his home at Greenway Court in Clarke County, Virginia. The arms are those of Fairfax, featuring a lion rampant, impaling Culpeper, featuring a bend or diagonal stripe. The Culpeper arms are those of Lord Fairfax’s mother, Catherine, Lady Culpeper, the heir to the Northern Neck Proprietary.

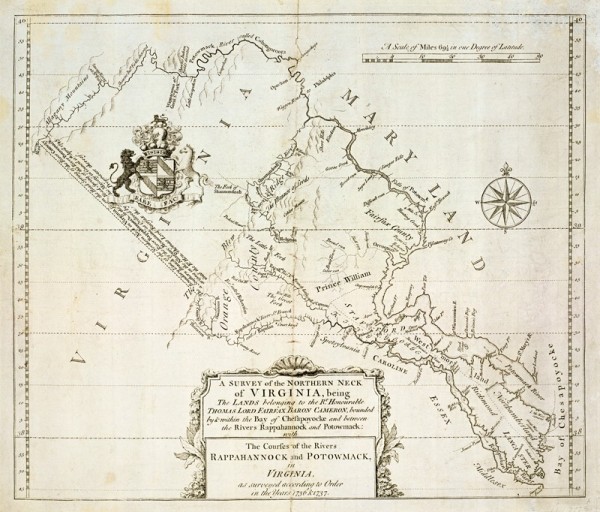

John Warner, A Survey of the Northern Neck of Virginia, being the lands belonging to the R.t. Honourable Thomas Lord Fairfax Baron Cameron, bounded by & within the BAY of Chesapoyocke and between the Rivers Rappahannock and Potowmack, in Virginia (London, 1745). 12" x 14". Engraving on paper. (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.) According to the terms of the Northern Neck grant, Lord Fairfax owned all of the land between the Rappahannock and Potomac Rivers, a claim disputed by Virginia’s colonial government. Fairfax requested that the Privy Council resolve the dispute, and the two sides employed surveyors to determine the bounds in 1736 and 1737. The Privy Council ruled in Lord Fairfax’s favor in 1745, leaving him with more than five million acres of land.

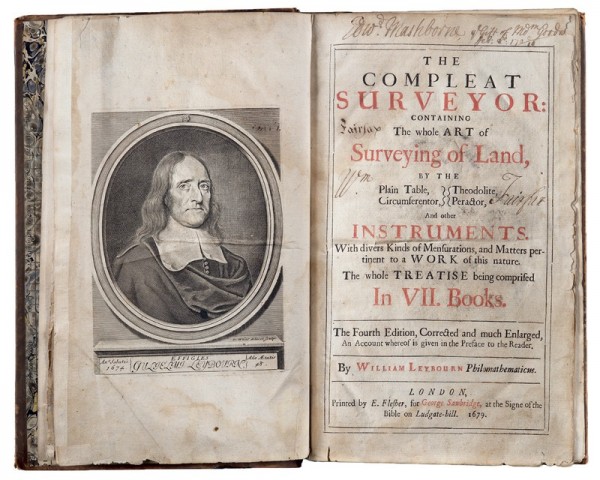

Title page of William Leybourn, The Compleat Surveyor (London, 1679). (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This book contains Colonel William Fairfax’s youthful signature, indicating that he likely learned the art of surveying using this copy. The Fairfaxes lent this book to George Washington, and he too likely used it to learn surveying as he began his career surveying for Lord Fairfax.

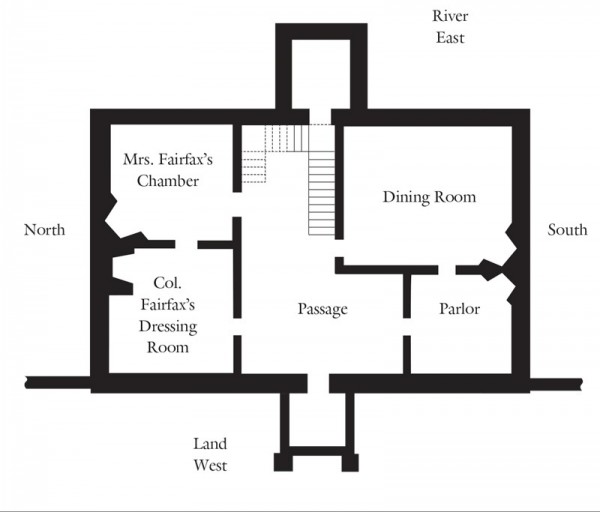

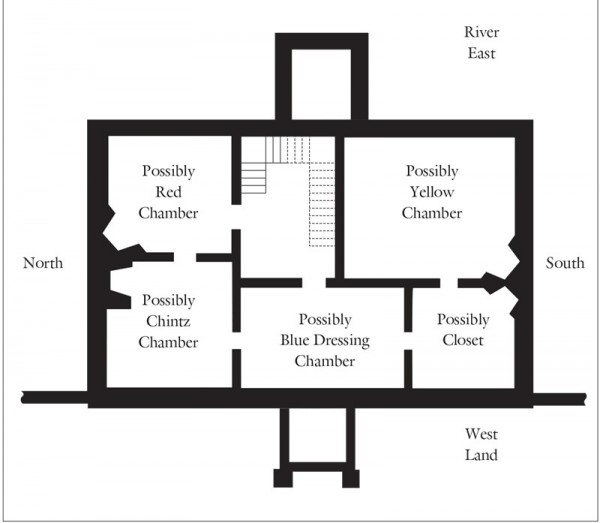

Conjectural first-floor plan of Belvoir, ca. 1740–1763, reflecting changes made by George William and Sally Fairfax in 1763.

Anne Byrd Carter, attributed to William Dering, probably Charles City County, Virginia, 1742–1746. Oil on canvas. 50 1/2" x 40". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.) The garden setting, likely at Westover in Charles City County, Virginia, closely resembles that found archaeologically at Belvoir.

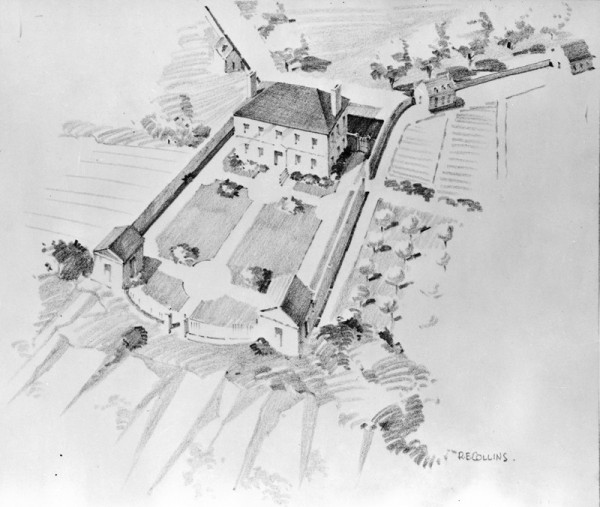

R. E. Collins, conjectural view of Belvoir and gardens, 1940–1950. (Courtesy, Library of Congress.) While fanciful, this drawing illustrates the major features of Belvoir as found archaeologically. The garden had a central pathway, but the remaining divisions are conjectural.

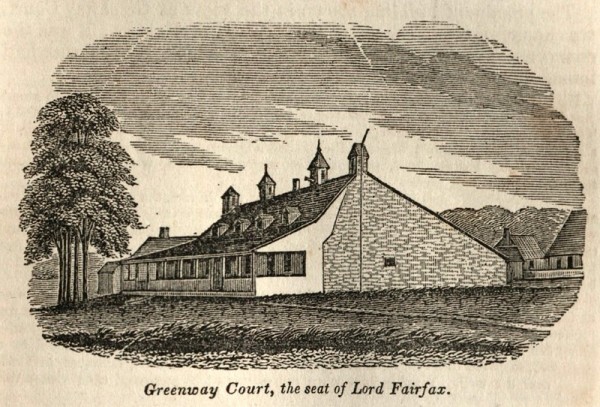

Greenway Court, Clarke County (formerly part of Frederick County), Virginia, illustrated in Henry Howe, Historical Collections of Virginia (Charleston, S.C.: S. C. Babcock and Co., 1845), p. 235. (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association.) Lord Fairfax lived at Greenway Court with his nephew Thomas Bryan Martin. The roof collapsed in 1834, and the house was torn down.

Robert Bénard, after Radel, Tapissier. Intérieur d’une boutique et differens ouvrages, plate 1, Encyclopédie, planches, sur les sciences, les arts libéraux, et les arts méchaniques, avec leur explication, vol. 9, edited by Denis Diderot et al. (Paris: Chez Briasson, 1762–1772). Engraving. 18 45/64" x 13 31/32". (Courtesy, Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts, University of Pennsylvania.) Many aspects of the upholsterer’s trade appear in this French engraving, including: case furniture, chair frames, upholstered seating, looking glasses, and mattresses for bedding.

Newcastle House, Clerkenwell Close, London, illustrated in William J. Pinks, The History of Clerkenwell, edited by Edward J. Wood (London: J. T. Pickburn, 1865), p. 97. (Courtesy, British Library.)

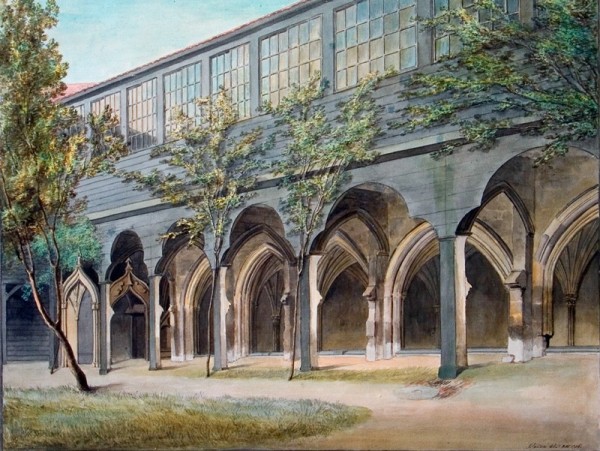

J. Sanders, Gomm and Company warerooms, Old St. James’s Church, Clerkenwell Close, London, 1786. (Courtesy, Society of Antiquaries.) Gomm and Company built its warerooms with continuous north-facing windows atop the south cloister of Old St. James’s Church. The “Gothick” arcade incorporates trefoils to harmonize with the style of the cloister. The firm sold furniture with gothic arches similar to those seen on the ground floor of their warerooms.

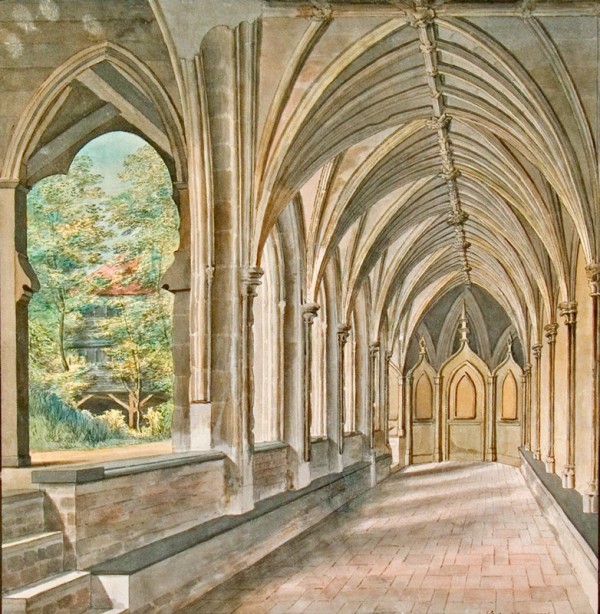

J. Sanders, Old St. James’s Church, remains of the south cloister, Clerkenwell Close, London, 1786. (Courtesy, Society of Antiquaries.) Gomm and Company added the “Gothick” screen at the end of the arcade.

Gomm and Company workrooms, Nuns’ Hall, Clerkenwell Close, London, illustrated in James Charles Crowle’s edition of Thomas Pennant, Some Account of London (London: Robert Faulder, 1793). (Courtesy, British Museum.) Gomm and Company built its work rooms atop the medieval remains of Nuns’ Hall.

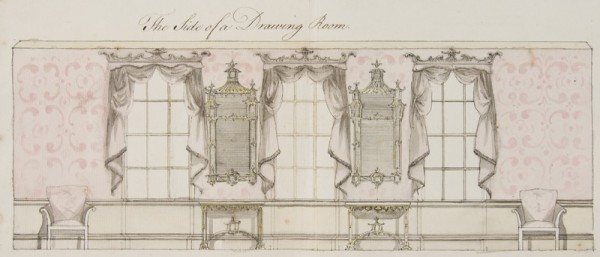

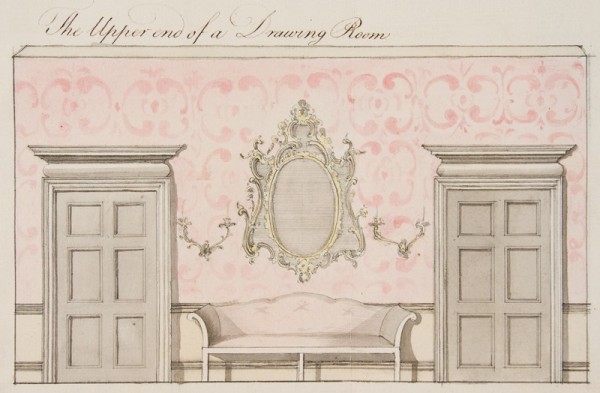

William Gomm, The Side of a Drawing Room, London, 1761. Ink and watercolor on paper. 7 3/4" x 15 3/4". (Courtesy, Winterthur Library, Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera.) Gomm’s depictions of four elevations of a room were probably for a potential client. The drawings demonstrate his knowledge of the latest design books, his ability to create new elements, and his capacity to furnish a room tastefully in its entirety.

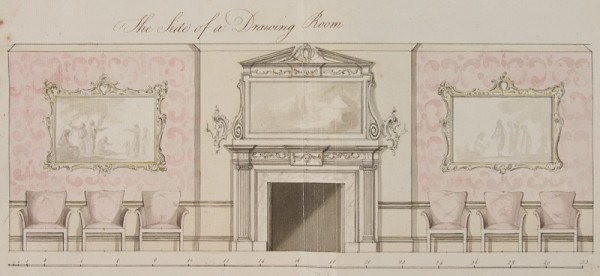

William Gomm, The Side of a Drawing Room, London, 1761. Ink and watercolor on paper. 8 1/4" x 16". (Courtesy, Winterthur Library, Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera.)

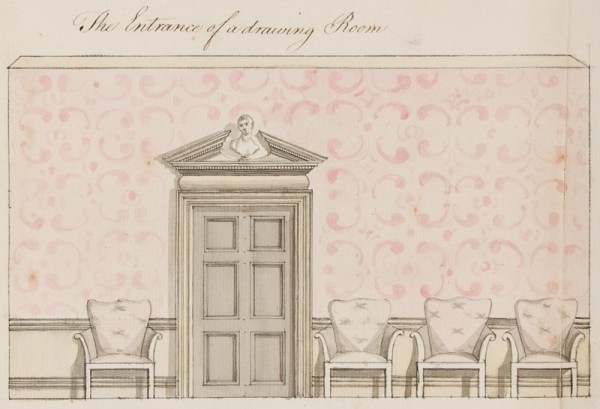

William Gomm, The Entrance of a Drawing Room, London, 1761. Ink and watercolor on paper. 7" x 10 1/2". (Courtesy, Winterthur Library, Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera.)

William Gomm, The Upper End of a Drawing Room, London, 1761. Ink and watercolor on paper. 7 1/4" x 11 1/4". (Courtesy, Winterthur Library, Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera.) English designers often created a focal wall in a room utilizing a sofa, candle branches, and looking glasses or pictures.

William Gomm, A Cloath’s Press, London, July 18, 1761. Ink and watercolor on paper. 8 3/4" x 8 1/4". (Courtesy, Winterthur Library, Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera.) The primary output of the Gomm firm was likely neat and plain pieces like this clothes press.

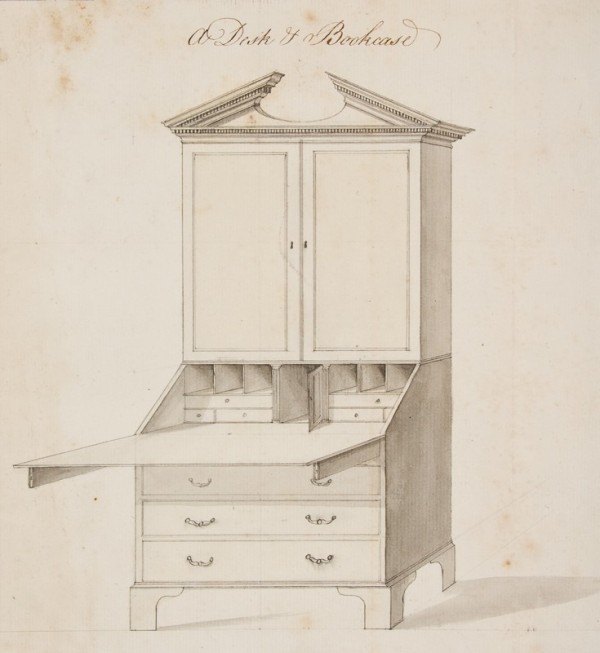

William Gomm, A Desk & Bookcase, London, August 15, 1761. Ink and watercolor on paper. 10 3/4" x 9 3/4". (Courtesy, Winterthur Library, Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera.)

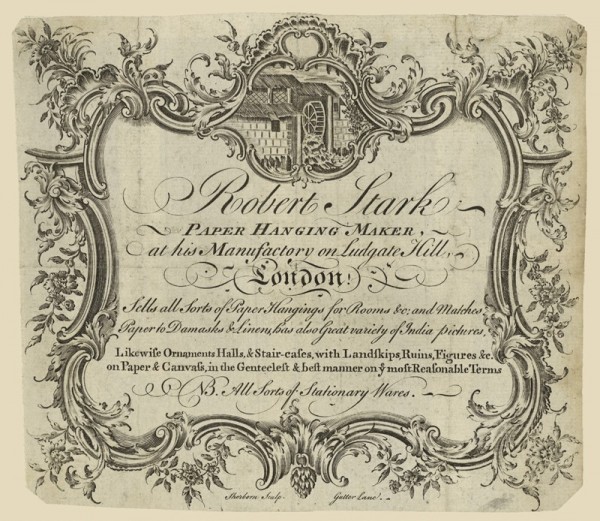

Thomas Sherborn, trade card for Robert Stark, London, ca. 1765. Creative Commons © Trustees of the British Museum.

Papier-mâché ceiling in the first-floor, southeast parlor of Philipse Manor, Yonkers, New York, ca. 1750. (Courtesy, Philipse Manor Hall State Historic Site, administered by the New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation; photo, Steven Spandle.)

Greenway Court Land Office, Clarke County, Virginia. (Courtesy, Dennis Pogue.)

Conjectural second-floor plan of Belvoir, 1763–1783.

An Interior with Members of a Family, attributed to Strickland Lowry, Ireland, ca. 1770s. Oil on canvas. 25" x 30" (Courtesy, National Gallery of Ireland.) The architectural wallpaper printed en grisaille is one of a number of patterns that could have been called “Painted Stucco.” The “Square Top Chairs” are likely similar to those in the central passage and Mrs. Fairfax’s chamber at Belvoir.

Chairs in perspective illustrated on pl. 9 in Thomas Chippendale, The Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker’s Director (London, 1754). (Courtesy, Winterthur Library, Printed Book and Periodical Collection.)

Wallpaper fragment recovered at Captain Lord Mansion, Kennebunkport, Maine, 1790–1810. Paint and polish or varnish on paper. (Courtesy, Historic New England.)

Johan Zoffany, Sir Lawrence Dundas with His Grandson, England, 1769–1770. Oil on canvas. 40" x 50" (Courtesy, Zetland Collection.) The carpet depicted by Zoffany would have been called a “Wilton Persian carpet” in the eighteenth century. Carpets of that type were based on Middle Eastern designs.

Spider-leg table, England, 1750–1770. Mahogany with mahogany and unidentified conifer. H. 27 1/2", W. 28", D. 26 7/8". (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

View showing the spider-leg table illustrated in fig. 30 with swing legs retracted and leaves down. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Samuel Courtauld, kettle, burner, and stand, London, 1753. Silver and rattan. H. 15 1/2", W. 11 1/8", D. 7 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This kettle is one of the more ornate pieces of English rococo silver with a history in colonial America. It is engraved with the coat of arms of Fairfax impaling Cary for George William Fairfax and Sarah (Sally) Cary.

Detail of the coat of arms on the kettle, burner, and stand illustrated in fig. 32. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

William Gomm and Company, chest-on-chest, London, 1763. Mahogany with oak and an unidentified conifer. H. 72 1/2", W. 46 1/4", D. 26" (Courtesy, Tudor Place Historic House and Garden; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

The back of the chest-on-chest illustrated in fig. 34, showing the stenciled ciphers “GWFx” and painted crate numbers. (Courtesy, Tudor Place Historic House and Garden; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The top case is marked “No. 2” and the bottom case is marked “No. 1,” designating the crates in which the pieces were shipped.

Detail of the back of the of chest-on-chest illustrated in fig. 34 showing the stenciled cipher “GWFx” and painted crate number “No. 2.” (Courtesy, Tudor Place Historic House and Garden; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

William Fairfax and George William Fairfax Account Book, 1742, 1748, 1760–1772. (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The account entry is for the double chest of drawers illustrated in figs. 34–36 along with crate numbers listed on the left.

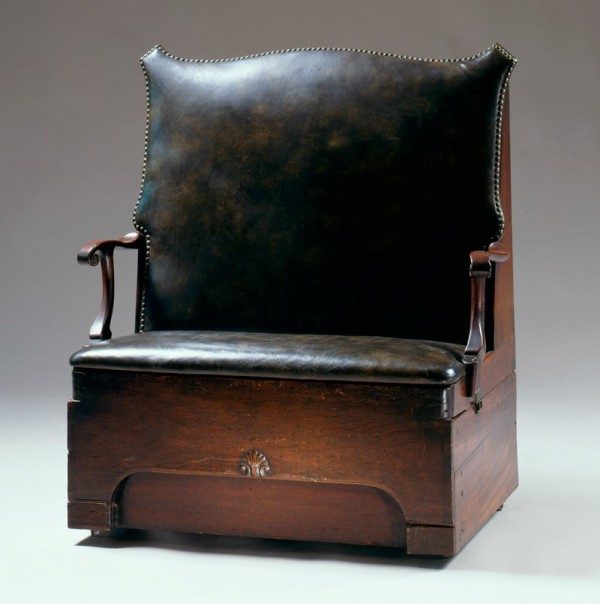

William Gomm and Company, shaving desk, London, 1763. Mahogany with oak and an unidentified conifer. H. 33 1/4", W. 15 1/2", D. 15 1/2" (closed). (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Open view of the shaving desk illustrated in fig. 38. (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The lid and shelf are restored.

Open and expanded view of the shaving desk illustrated in fig. 38. (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The outer frame is original, with mortices indicating the positions of the mirror and the central brace.

Settee bedstead, England, 1760–1780. Mahogany with beech; leather, wool, linen, brass, iron. H. 49 1/2", W. 40 7/8", D. 28 1/4" (closed). (Courtesy, Sotheby’s.)

Open view of the settee bedstead illustrated in fig. 41. (Courtesy, Sotheby’s.) The curtains slide on an iron compass rod that is bent into a square, obviating the need for three separate curtains and keeping more heat inside. This feature occurs frequently on beds where the compass rod extends around the outside of the footposts and beneath the cornice.

John Singleton Copley, Portrait of a Lady, probably Boston, Massachusetts, 1771. Oil on canvas. 50" x 40". (Courtesy, Los Angeles County Museum of Art.)

Papier-mâché wallpaper border, England, ca. 1765. (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.) This fragment was found in Governor John Wentworth’s house in Portsmouth, New Hampshire.

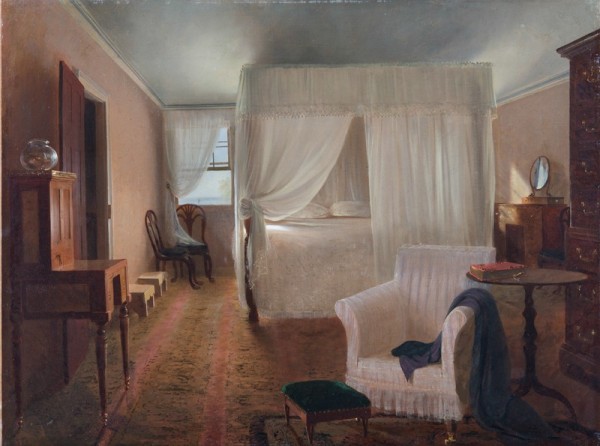

John Gadsby Chapman, The Bed Chamber of Washington, in Which he Died with all the Furniture as it Was at the Time. Drawn on the Spot by Permission of Mrs. John Washington of Mount Vernon, Virginia, 1835. Oil on canvas. 21 9/16" x 29". (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The artist depicted the Washingtons’ Philadelphia-made three-rod bed. The rods are positioned between the bedpost just below the cornice, and the curtains hang from metal rings. This was a common and inexpensive treatment in the period. The chest-on-chest in the right corner is illustrated in fig. 34.

Reproduction bed in the chintz chamber in Mount Vernon, Mount Vernon, Virginia. (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association; photo, Matthew Briney.) This bed is a conjectural reproduction of the chintz bed with drapery curtains George Washington purchased from Philadelphia upholsterer John Ross in 1773. The drapery curtains are tacked to the cornice and raised and lowered with line secured to brass rings on a pulley system installed in the cornice. This type of bed was the most expensive and complicated in the period.

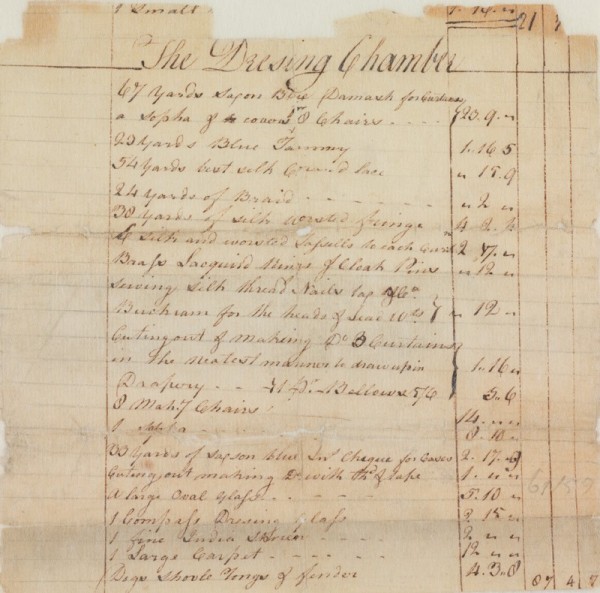

“The Dressing Chamber” from George William Fairfax’s inventory of Belvoir, 1773. (Courtesy, Virginia Museum of History and Culture.)

John Watts, pewter hot water plates, London, ca. 1765. Pewter. H. 97/16", W.113/16", D. 17/8". (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) These may be three of the “10 Pewter Water plates” Washington purchased at the Belvoir auction along with other kitchen items.

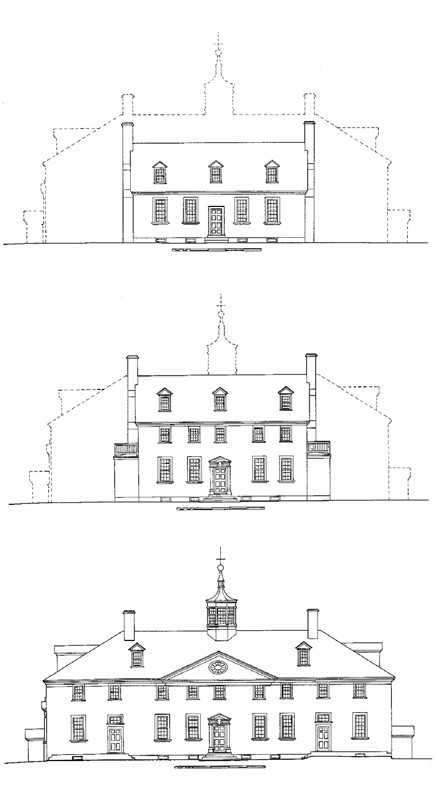

Mount Vernon, Mount Vernon, Virginia, 1734–1787. (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association.) George Washington expanded Mount Vernon, the house his father built in 1734, twice. He first added a second story and a garret between 1757 and 1759. Then, in 1774 George began building two wings, a project he completed in 1787. (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association.)

Charles Willson Peale, Colonel George Washington, Virginia , 1772. Oil on canvas. 50" x 40". (Courtesy, Washington-Custis-Lee Collection, Washington and Lee University, Lexington, Virginia.)

Charles Willson Peale, Martha Washington, Virginia, 1772; refashioned ca. 1790. Watercolor on ivory, gold, copper alloy, glass. 2 3/8" x 1 13/16". (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

“Small Dining Room” at Mount Vernon, Mount Vernon, Virginia. (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association; photo, Walter Smalling.)

William Bernard Sears and anonymous “stucco man,” chimneypiece in the “Small Dining Room,” Mount Vernon, 1774. (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Sideboard table, England, 1740–1757. Black walnut; marble. H. 29 7/8", W. 28 1/4" D. 25 7/8". (Courtesy Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The knee blocks are missing.

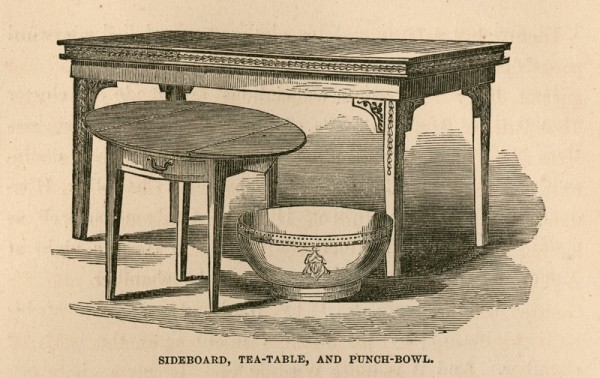

Sideboard table, Pembroke table, and punch bowl illustrated in Benson J. Lossing, Mount Vernon and Its Associations: Historical, Biographical, and Pictorial (New York: W. A. Townsend and Company, 1859), p. 317. The author illustrated the Fairfax sideboard when it was at Arlington House, but his depictions are only partially accurate. Gomm and Company’s invoice notes that the sideboard table they provided had no inlay.

Reconstruction (1952) of the bottle cistern William Gomm and Company furnished for George William and Sally Fairfax in 1763. Mahogany; lead, brass. H. 18 3/8" x W. 23" D. 21 1/4". (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The brass bands, the lion mask handles, and the staves to which the handles are attached are the only surviving components of the “Ovall Bottle Cistern on a Frame” George Washington purchased from George William Fairfax.

George Washington’s study, Mount Vernon, Mount Vernon, Virginia. (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association; photo, Robert Lautman.) George Washington added the built-in bookcase in 1786.

Front parlor, Mount Vernon, Mount Vernon, Virginia. (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The front parlor sofa, chairs, and window curtains are recreated utilizing the documentary evidence provided by the Fairfax account book and comparison with surviving period pieces with similar features.

Front parlor, Mount Vernon, Mount Vernon, Virginia. (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Guests arrived through the central passage visible in the distance.

Front parlor, Mount Vernon, Mount Vernon, Virginia. (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The front parlor became the formal entry to the two-story New Room visible through the doorway.

New Room, Mount Vernon, Mount Vernon, Virginia. (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

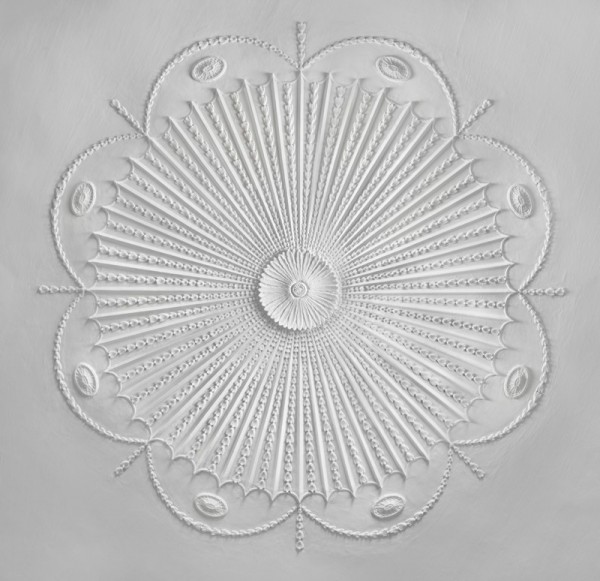

Richard Tharpe for John Rawlins, front parlor ceiling, Mount Vernon, Mount Vernon, Virginia, 1787. (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) George Washington updated the ceiling with neoclassical ornament to unite the space visually with the New Room.

On a warm summer day in 1763, a London-made carriage pulled by four of the finest horses in the Virginia Colony rounded the carriage circle of a large brick mansion. The enslaved postilion dressed in the red-and-white livery of the Washington family eased the horses to a stop just in front of a massive paneled door. George and Martha Washington, the passengers, knew this mansion, called Belvoir, quite well, as it was the home of their closest friends and nearest neighbors, George William and Sally Fairfax. The Washingtons had not seen their friends in three years because the couple had been on an extended trip to England. The Fairfaxes’ butler greeted the Washingtons and showed them into the dining room, but as the couple passed through the house they noticed major changes. The Fairfaxes had emptied Belvoir, one of the grander dwellings on the Potomac, of its furniture, stripped much of its architectural detail, and made the house ready for a full redecorating campaign. Sixty massive wooden crates, stenciled with the cypher “GWFx” for George William Fairfax, were piled high in the first-floor rooms. The crates contained furniture, upholstered goods, looking glasses, wallpaper, mantels, and papier-mâché ceiling ornament sufficient to furnish the entire house.

These are mere imaginings of the way in which the Washingtons first encountered the Fairfaxes’ purchases. Unfortunately, George Washington’s diary for that summer is lost but, given the two couples’ close friendship and proximity of their respective homes, it is entirely plausible that the Washingtons called on the Fairfaxes soon after their homecoming. On that first visit, the Washingtons were likely astounded at what they saw. Although George and Martha were accustomed to receiving shipments of furniture from their London factors—a set of chairs or a few tables in one shipment or the other—they had never seen anything on this scale. The Fairfaxes had commissioned the entire contents of their house from a London upholsterer, the interior designer of the day, and had them shipped 3,000 miles across the Atlantic Ocean. The Fairfaxes no doubt intended that these imported furnishings would confirm their status as taste-makers at the apex of Virginia society. To date there is no other known instance of an American colonist furnishing an entire house from an English upholsterer. While the Washing-tons did not record their impressions of the Belvoir renovation, they signaled their approval in a different manner. Just over a decade later, when the Fairfaxes moved permanently to England at the outbreak of the American Revolution, the Washingtons either purchased or were given nearly a third of the London-made furniture from Belvoir, and they continued to use much of it for the rest of their lives.

In September 2013 George William Fairfax’s account book surfaced at auction, and the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association purchased it. The document lists all the purchases the Fairfaxes made in London between 1760 and 1772, offering remarkable insight into the material lives of one of the wealthier families in colonial America. Belvoir burned in 1783, leaving behind only a foundation and archaeological remains. Although scholars have long acknowledged Belvoir as the most architecturally significant and influential eighteenth-century house in Fairfax County, Virginia, its loss, the absence of images, and a dearth of documentary references have prevented a full understanding of the property. The emergence of the Fairfax account book and its subsequent examination in conjunction with the archaeological record have revealed incredible detail about the rooms at Belvoir and the manner in which the Fairfaxes furnished them. The first four pages of the volume are the most significant to understanding the house: they feature an invoice for furniture and upholstered goods purchased from the London firm of William Gomm and Son and Company for use at Belvoir (figs. 1-3). Read in conjunction with the archaeological remains of the house, a 1773 inventory held by the Virginia Historical Society, and a few surviving furnishings, the account book allows modern scholars to reconstruct much of Belvoir’s appearance. By positioning George William and Sally Fairfax’s material choices within the context of their biographies, their social aspirations, and their family dynamic, a new image emerges of a couple utilizing material goods to establish and confirm their position in society.[1]

This article traces the story of the Fairfax furnishings and the critical role they played in the lives of George William and Sally Fairfax, and later, the lives of George and Martha Washington. The central narrative is George William’s declining relationship with his cousin, Thomas, Lord Fairfax, and his continuing attempts to regain Thomas’s favor. Lord Fairfax owned the largest land grant in Virginia, known as the Northern Neck Proprietary, and his patronage through position and inheritance was critical to George William’s success in life. At a critical juncture in the narrative, George William becomes heir apparent to his cousin’s title—a title with no fortune—and the couple decides to use the furnishings of their Virginia home to assert their status as English aristocrats in the British colonies. They construct two exceptional rooms, a dressing room and a bedchamber, for Lord Fairfax’s use, in an effort to bring them back into his good graces. In so doing, the couple fails to see that the aristocratic behaviors embodied in the furnishings of these two rooms are no longer suited to the rapidly changing perspectives of Virginia colonists as the Revolutionary War approaches. Defeated and out-moded, the couple moves permanently to England in 1773, and their furniture takes on new life.

The furniture is sold at auction, presenting an excellent opportunity for local planters to acquire fashionable British goods at a time when trade is cut off to the mother country. George and Martha Washington utilize this opportunity as they expand Mount Vernon to update two of the more public rooms in the house, their dining room and front parlor. For the Washingtons, the furniture represents an opportunity to furnish their rooms with goods that have been tried and approved by one of the grandest families in the colony. Now, the rediscovery of the Fairfax account book and a reexamination of the corresponding documentary record allow scholars to trace those furnishings through time and space and to examine their every detail at a granular level in a manner previously not seen in American houses. By melding furniture, style, and personal biography into a single narrative, the Fairfax furnishings offer a lens into the lives of two of the most important families in Virginia and how they used furniture to define themselves and their standing in society.[2]

Fairfax Proprietary

George William Fairfax’s father, Colonel William Fairfax, moved to Virginia in 1734 to act as land agent for his cousin Thomas, 6th Lord Fairfax of Cameron, the single largest landowner in colonial Virginia. Lord Fairfax owned the Northern Neck Proprietary, which consisted of all of the land between the Potomac and Rappahannock Rivers from their emergence in Chesapeake Bay to their headwaters. Thomas, 6th Lord Fairfax managed the land through a series of proprietary land agents resident in the colony (fig. 4). Lord Fairfax might have left his Virginia lands to the management of others had it not been for a series of three unfortunate circumstances. First, his father, Thomas, 5th Lord Fairfax, had squandered much of the Fairfax estate in England, leaving little money and diminished lands to meet the baron’s many financial obligations and forcing the young squire to be frugal at an early age. Second, Lord Fairfax learned that his land agent, Robert “King” Carter of Corotoman, had unduly enriched himself by issuing hundreds of thousands of acres of proprietary land to himself, his children, and his grandchildren, making him the wealthiest man in Virginia. Third, the exact boundaries of the proprietary were not firmly established, and the Virginia Colony began questioning the boundaries after Robert “King” Carter’s death in 1732. The Potomac and Rappahannock Rivers had numerous tributaries, and determining exactly which ones constituted the “headwaters” would make a crucial difference in the total acreage owned by the baron (fig. 5).[3]

Lord Fairfax required an administrator to help consolidate power and make the proprietary profitable, and he hired his first cousin and childhood friend, Colonel William Fairfax, to leave his post in Massachusetts and come to take control of Lord Fairfax’s Virginia lands. Colonel William Fairfax had all of the necessary skills. At an early age, William had embarked on a career in the colonies and held a series of lucrative public offices. He began as collector of customs for Barbados before becoming the chief justice and later governor of the Bahamas. He then moved to the Massachusetts Bay Colony where he served as collector of customs for Salem and Marblehead. In these positions, he proved himself an able bookkeeper capable of tracking customs revenue for the Crown. He also had learned the art of surveying while young, a skill that would prove vital in Virginia, where he oversaw the establishment of the proprietary’s boundaries and approved the many surveys that accompanied individual land patents (fig. 6). In 1734 William Fairfax moved his young family to Virginia in order to take stock of Lord Fairfax’s land holdings and prepare for the 1735 Lord’s arrival in the colony. He immediately assumed the post of collector of customs for the South Potomac. William was later elected to the House of Burgesses and eventually appointed president of the Governor’s Council. In each of these Virginia offices, he served as an advocate for the interests of the proprietary.[4]

After thoroughly exploring the lands in his charge, Col. Fairfax began amassing property at the heart of the bustling proprietary in 1736. On the Potomac River in Prince William County, he planned to build a large house to establish permanently his family and to serve as the proprietary land office. Located on the edge of the Tidewater region, Prince William County opened for settlement in 1722, attracting colonists from the lower Chesapeake desperate for fertile tobacco-growing land. Within a decade of the colonel’s initial purchases, Prince William County’s population had grown so large that the legislature resolved to divide it into several counties. The area north of the Occuquan River, which included the colonel’s land, became the County of Fairfax. In 1748 the inhabitants of Fairfax County petitioned the House of Burgesses to establish a town and port at the head of navigable waters on the Potomac. They named the town Alexandria and hoped it would serve as an entrepôt for trade with the Ohio Territory.[5]

Belvoir

Sometime between 1736 and 1741 William Fairfax built the first prodigy house in the region, naming it Belvoir after a family holding in Yorkshire. For him, the house and surrounding grounds were more than an aspirational statement; they confirmed his status as a member of the trans-Atlantic British elite. The fourth son of a baron’s second son had built his reputation, and a large income, as a colonial administrator, and he was prepared to set down roots and permanently establish his family in Virginia. Colonel Fairfax intended to impress when he built a grand two-story Georgian double-pile house that likely had five bays. Constructed of brick with a molded water table and a footprint of 56' x 37', the house immediately signified its role as both the dynastic seat of the Fairfax family and the administrative center of the Fairfax proprietary. In size and degree of finish, it compared favorably with many of the larger brick dwellings of the lower Tidewater region (namely, Sabine Hall, 1738; Shirley, 1738; and Cleve, 1746). The first floor of Belvoir contained “four convenient Rooms” on either side of “a large passage,” which most likely stretched through the house and included a large central staircase (fig. 7). During Col. Fairfax’s ownership, the four rooms on the first floor likely included a large dining room, a smaller parlor, a bedchamber, and a study or office. The second floor had “five Rooms,” almost certainly all bedchambers and storage, and a stair passage.[6]

The grounds surrounding the house were among the more highly cultivated in the colony. The mansion house occupied a dramatic bluff at the crest of a ridge overlooking the Potomac River. On the land side, there was a large carriage circle flanked by two outbuildings, likely the proprietary land office and kitchen. Curved brick walls connected the two buildings to the main block of the house and to the brick walled court or garden on the river side. The archaeological remains of the riverside court likely closely resembled the one depicted in William Dering’s 1742–1746 portrait of Anne Byrd Carter (Mrs. Charles Carter) (fig. 8). In that picture, Carter stands before a court of carefully manicured grass surrounded by a brick wall with wooden palings. In the distance, a small brick garden house frames the view. To maintain symmetry, there was likely a matching building on the other side, as there was at Belvoir. A curved brick wall extends between the two buildings and there was almost certainly a gate at the center, as at Belvoir. At Belvoir, the curved wall sat at the edge of the bluff overlooking the river, accentuating the view from the house (fig. 9).[7]

Colonel William Fairfax’s Family

Although Lord Fairfax had no wife or children, Col. Fairfax did. By the time the latter moved to Belvoir, he had six children by two marriages. By his first wife, Bahamian Sarah Walker, Fairfax had four children: George William, Thomas, Anne, and Sarah. Sarah, his wife, died in childbirth in 1731, and William quickly married Deborah Clarke of Salem, Massachusetts, by whom he had three children: Bryan, William Henry, and Hannah. The two daughters from the first marriage wed prominent citizens of Fairfax County. Anne married Lawrence Washington of Mount Vernon, the elder half-brother of George Washington, and Sarah married British merchant John Carlyle of Alexandria. The two surviving sons, George William and Bryan, married two sisters, Sarah (Sally) and Elizabeth Cary, daughters of Colonel Wilson Cary of Ceelys, one of the wealthier men in Virginia and a member of the Governor’s Council.[8]

Lord Fairfax took an early interest in the colonel’s eldest son and heir, George William Fairfax, and sent him to England at age eleven to be educated at his expense. Once George William’s schooling was complete, Lord Fairfax appointed him deputy land agent and brought him back to Virginia, setting him up to assume his father’s role and eventually to take over management of the proprietary. In 1746 George William accompanied his father and representatives of both Lord Fairfax and the colony to run the boundary line of the proprietary. Two years later, during the rush to issue land grants after the boundary’s finalization, William Fairfax sent George William and sixteen-year-old George Washington to survey a number of plots of land across the Blue Ridge Mountains. While this trip whetted George Washington’s appetite for the American frontier, it seems to have had the opposite effect on George William. That same year, he married Sally (Sarah) Cary and settled into the domestic life of a Tidewater gentleman at his father’s home on the banks of the Potomac River. George William’s preference for the genteel Chesapeake lifestyle was at odds with the needs of the proprietary and Lord Fairfax, who required a land agent close by to the major land grants.[9]

Although George William Fairfax was not as much of a frontiersman as his father, he was far from idle. At Belvoir, he managed a 2,000-acre tobacco plantation, a commercial fishery, and stone quarries, all worked by enslaved laborers. At his “Shenandoah” property in Frederick County, he built an iron foundry while also speculating in western lands as a member of the Ohio Company. He continued to serve the political interests of the proprietary through his election to the House of Burgesses as a representative for Frederick County, where he also served as justice of the peace and a colonel of the county militia during the French and Indian War. He eventually became a member of the Governor’s Council in 1768, a position that allowed him to advocate for the interests of the proprietary.[10]

In 1745 the Privy Council finalized the boundaries of the Northern Neck Proprietary as surveyed, allowing Lord Fairfax to open the western lands to settlement. Lord Fairfax recognized the economic necessity of moving closer to his new land grants. In 1749 the baron erected a small log cabin on a plot of land he called Greenway Court near the fledgling town of Winchester (fig. 10). Winchester occupied a strategic location on the Great Wagon Road, the thoroughfare taken by large numbers of German and Scotch-Irish immigrants eager to settle the fertile farmland beyond the Blue Ridge Mountains. George William chose to remain at Belvoir rather than follow Lord Fairfax, an act that created a rift between the two men from which they never recovered. As long as Col. Fairfax lived, however, the proprietary land office remained at Belvoir and the agent’s title in George William’s hands. In the meantime, Lord Fairfax sought someone to help manage the burgeoning western business at Greenway Court, and he brought his nephew Thomas Bryan Martin from England in 1751 to live with him and train in the business. George William viewed Martin’s presence as a threat to his position as land agent, and the two men quickly developed a hostile relationship.[11]

In 1747 George William became heir presumptive to his cousin’s title, elevating his status in English society. In the British peerage, most titles descend in the direct male line. If the current holder fails to produce a male heir, the title passes to the closest male relative of the peer in a direct male line from the original holder. Although Thomas, 6th Lord Fairfax was a confirmed bachelor, his brother, Robert (later 7th Lord Fairfax) had produced a male heir, presumably securing the Fairfax title in the Culpeper line. After the child’s death in 1747, Robert sought a second wife and married Dorothy Best on July 15, 1749. Her death the next year and Robert’s subsequent failure to remarry left George William all but certain that he would inherit the title, albeit one with no fortune. The Fairfax lands in Yorkshire were no more, and Lady Fairfax’s five-sixth share in the proprietary would pass to the nearest Culpeper relations. George William could only hope that he would be left the one-sixth share that Lord Fairfax inherited in his own right as a means of maintaining a lifestyle appropriate to the title.[12]

On September 3, 1757, Colonel William Fairfax died after leading the proprietary through the transition from an ill-defined land grant producing little income to a fully surveyed grant of more than five million acres with rapidly expanding settlement and increased revenue. His loss left a hole in the lives of both the proprietor and the Fairfax family and further complicated the ties between Lord Fairfax and George William. George William inherited all of his father’s land at Belvoir, all of his household goods, and three slaves. Almost immediately after his father’s death, George William boarded a ship bound for England to appeal to the Board of Trade for his father’s former post as collector of customs for the South Potomac, a position worth between £500 and £600 annually.[13]

George William Fairfax returned to Virginia in 1758, having secured his position as collector of customs for the South Potomac. Not long after, he received word from Yorkshire that his uncle Henry Fairfax of Towlston Grange, his father’s eldest brother and heir to the family fortune, had died, leaving him a sizable Yorkshire estate as next in line. The Reverend Thomas Moseley, caretaker of the property, was almost jubilant when he wrote to George William with news of Henry’s death. He noted that George William needed “to bring no more money into England than what is necessary to defray yr voyage here” and hinted that his uncle’s affairs turned out to be “greatly beyond [his] expectation.” Moseley refused to “properly condole with [George William] for his Departure,’’ suggesting that Henry Fairfax’s “life was of no service to his relations” and that Henry “was daily surrounded with a set of low, mean men.” Less than two years after his previous visit to England, George William and Sally prepared to embark for the mother country yet again “to put a stop to the foreclosing of the Mortgage on the Redness Estate,” one of his grandmother’s mortgaged estates. He wrote hastily to Lord Fairfax on May 1, 1760, requesting another leave of absence, this time for between twelve and eighteen months. Yet again, the proprietary would be left without a land agent. After missing Lord Fairfax in Williamsburg in the summer of 1760, George William wrote again, but this time he noted that Lord Fairfax could send written consent for his absence to his agent in London. Lord Fairfax never replied to either letter, and George William and Sally sailed for London. By the time the couple embarked, George William complained to Lord Fairfax that the income at the Belvoir land office had slowed so much that he could barely pay for a clerk and stationery.[14]

Purchasing in London

With inheritances from his father and uncle and revenue from both his new post and his fees as land agent, George William could sustain a substantial lifestyle—but not quite the one he believed was most suited to his position as heir presumptive to his cousin’s barony. George William had an encumbered financial position, and he wrote to Lord Fairfax complaining that should he survive Lord Fairfax and his brother “the great Estates formerly annexed to the Titles have long since changed their Channel.” He worried that it would be his lot “to drag Titles which I can by no means Support the dignity of.” Rather than live within their means, George William and Sally chose to improve their material surroundings to accord with their new social station in a manner appropriate to the dignity of the title. As material culture scholars have shown, men and women with small mercantile and landed estates attempted to confirm their social standing by building houses and purchasing furnishings appropriate to their station rather than presuming to ape the upper echelons of aristocracy. By residing in the proper classical home and furnishing it with the correct goods, the Fairfaxes participated in a universal British language of polite sociability. They hoped that Lord Fairfax would leave them the one-sixth share of the proprietary that he controlled in his own right to support the title.[15]

The Fairfaxes remained in York with family and attempted to resolve complex inheritance issues for the next two and one half years. Although the couple likely always intended to return to Virginia in the spring of 1763, they hastened their preparations when they learned that on February 10, 1763, the British had signed the Treaty of Paris, officially ending the French and Indian War. With the Atlantic Ocean once again open to uninhibited trade and French vessels no longer threatening their British rivals, the couple quickly realized that “ships would sail as they could get ready” rather than wait for escort by vessels from the British Navy. Concerned that they would not be able to purchase all of the goods they needed before the vessel on which they intended to travel departed, George William and Sally boarded their horse-drawn chaise on February 15 and began the four-day overland journey to London.[16]

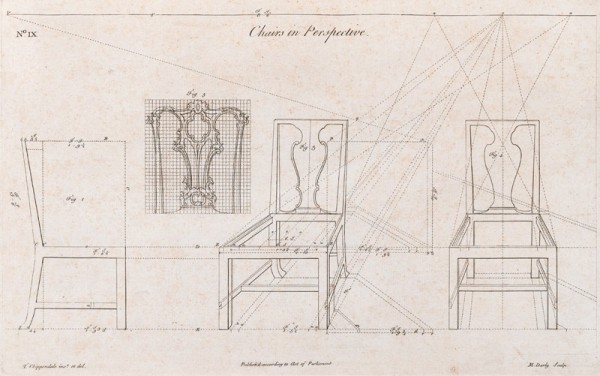

Two days after arriving in London, George William and Sally visited the warerooms of William Gomm and Son and Company. Their London agent, Samuel Athawes, or one of their relatives might have recommended the firm to the couple. London upholsterers by then had evolved as a trade beyond the traditional role of fitting up “Beds, Window-Curtains, and Hangings” and covering “Chairs that have stuffed Bottoms” to become connoisseurs “in every Article that belongs to a House” (fig. 11). Upholsterers either employed or marshaled a diverse range of tradesmen, including chair makers, cabinetmakers, glass grinders, carvers, finish specialists, woolen drapers, paper stainers, and metal smiths. In 1763 London cabinetmakers and upholsterers were at the height of their trade. The year before, Thomas Chippendale issued the third edition of The Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker’s Director, a publication that a decade before had established cabinetmakers and upholsters as taste-makers in their own right. Over the next ten days, George William and Sally worked with the Gomm firm and other suppliers to outfit completely their Virginia home.[17]

While upholsterers with aristocratic connections, such as Chippendale or Vile and Cobb, occupied warerooms in the fashionable shopping district behind St. Paul’s Cathedral, second-tier firms, including Gomm and Son, often set up shop on the outskirts of the city, where land was cheaper and space more plentiful. In 1736 William Gomm moved into Newcastle House, former home to the Dukes of Newcastle, in Clerkenwell Close on the northern edge of the city and set up shop as a cabinetmaker (fig. 12). Clerkenwell Close had once been an aristocratic enclave, but during the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries it transitioned into a working-class neighborhood occupied by tradesmen. The outdated aristocratic house offered a home for William Gomm, and the firm used Newcastle House as the address for its “cabinet wareroom.” Nearby, on the remains of the medieval cloister of St. Mary’s nunnery, William and Richard Gomm built “the most compleat & extensive Suit of Ware-rooms in London,” a two-story wooden building with continuous north-facing windows (figs. 13-14). Their workrooms occupied additions built above the old Nuns’ Hall (fig. 15). The Gomms spent more than £5,000 improving their properties in the close, and while there is little information regarding the number of tradesmen they employed, the sheer scale of the firm’s property suggests that their output was massive.[18]

Typically, the upholsterer visited the home of a client to take measurements and make preliminary sketches before presenting his ideas to the client. Consumers who had fewer resources or lived in distant locales could reduce costs by taking the measurements themselves and hiring local craftsmen for installation. This approach entailed additional risk: if the goods arrived and they did not fit, the burden was on the client rather than the upholsterer. When the Fairfaxes visited Gomm and Son, the couple must have brought a floor plan with detailed measurements of Belvoir’s rooms to facilitate the purchase of window curtains, carpets, and furniture in the proper sizes. With that degree of information, the Gomms could design and furnish virtually every aspect of an interior. Evidence suggests that the firm did precisely that for each room at Belvoir.[19]

The ability to furnish a room en suite was a defining attribute of the eighteenth-century upholsterer. Four sketches executed by William Gomm (likely the younger) in 1761 illustrate the type of work his family firm offered its clients (figs. 16-19). The furnishings and decorations depicted in the sketches are probably more elaborate than those provided for Belvoir, but they show how upholsterers like the Gomms achieved harmony and resonance: there are ten matching chairs, a sofa, and window curtains with identical red fabric; a pair of pier tables with pagodas echoing those on the mirrors above; a “modern” or rococo looking glass with ornament similar to that on the large paintings and the window cornices; and a red damask (either wallpaper or fabric) covering the walls that pulls the entire composition together. In the colonies, achieving this level of coordination was difficult, even in the cities, where inhabitants were forced to rely upon goods—particularly textiles and wallpapers—imported from abroad.[20]

On February 24 George William Fairfax, almost certainly accompanied by Sally, returned to Gomm’s warerooms “to choose Furniture &c in order to have an Estimate.” The process of selecting furnishings for an entire house must have taken all day, and the couple did not return to their lodgings until dinner. While the Gomm firm could have produced almost anything in the rococo taste for the Fairfaxes, the couple’s time constraints, the prevailing aesthetic of their social stratum, and budget seem to have pushed them towards stock items. Eighteenth-century British cabinetmakers and upholsterers kept well-made but conservatively designed items on hand to supply the middle-class market and to furnish lesser rooms of the aristocracy. Such stock-in-trade tended to be “neat,” or “elegant, but without dignity,” and “plain,” or “void of ornament, simple.” The vast majority of the furniture enumerated in the Fairfax estimate appears to have been in this “neat and plain” style (figs. 20-21). The distinguishing features of this type of furniture were high quality primary woods and hardware, and proportions, shapes, and moldings based on the classical orders.[21]

Like so many of their contemporaries, the Fairfaxes went to London to familiarize themselves with the latest tastes, but they were willing to buy their furnishings elsewhere if they could find similar items for less money. British consumers often found these cheaper prices in smaller cities, where cabinetmakers and upholsterers could operate with less overhead and less competition. The Fairfaxes, who were based in Yorkshire, considered acquiring some of their furnishings in York. George William’s “List of Household & Kitchen Goods to be Purchased” has headings designated “London Price” and “York Price.” The former records the prices received from Gomm and Son, but the latter is not filled out. Apparently, comparison shopping required more time and effort than the Fairfaxes could afford before returning to Virginia.[22]

While Gomm and Son could provide many of the necessary furnishings in-house, they did not stock wallpaper, papier-mâché ornament, or architectural woodwork. For wallpaper and papier-mâché ornament, the firm worked with Robert Stark, a paper stainer with a wareroom at Ludgate Hill, a fashionable shopping district near St. Paul’s Cathedral (fig. 22). Stark described himself as a “paper hanging maker” who sold “all Sorts of Paper Hangings for Rooms.” His inventory probably included papers made both in his shop and from other English and French establishments, as well as expensive “India,” or Chinese, papers. Stark also advertised papers “to [match] Damasks & Linens” and “a great Variety of papier mache . . . Ornaments modern and antique” (fig. 23). The Fairfaxes purchased enough wallpaper and border to outfit six rooms, papier-mâché ornament for the ceilings of two of the more formal spaces, and a variety of “branches,” girandoles, and brackets. For architectural woodwork, they turned to London carver Thomas Speer, although it is not certain that he was part of the Gomm network. Speer sold the couple “3 New Viend [veined] Marble Pieces” with varying amounts of ornament to fit inside three carved “[wood] Mantils wth. frees & Cornice” for three of the finer rooms in Belvoir. The mantels and friezes probably resembled the one drawn by Gomm in his plan of the mantel wall of a room.[23]

Returning to Belvoir

When the Fairfaxes set sail with their furnishings in the spring of 1763, trouble was brewing back in Virginia. Lord Fairfax had cut off communication with George William and moved permanently to the western frontier, depriving the latter of his job as land agent. In 1761 Lord Fairfax had a new land office constructed at Greenway Court, and he named Thomas Bryan Martin as land agent (fig. 24). There the two men lived in danger as the French and Indian War played out around them, and many of their neighbors fended off attacks from Native Americans. George William had urged Lord Fairfax to move to Belvoir for several years, and he was stunned by these developments. For the remainder of his life, he failed to see that his failure to move to the backcountry with his cousin to act as land agent was the main cause of the two men’s strained relations, and he believed that Martin had turned the proprietor against him.[24]

Through their purchases and the manner in which they furnished Belvoir, George William and Sally signaled their intention to live according to their station in society, but in doing so, their choices became an implicit criticism of the current Lord Fairfax’s lifestyle. Robert Fairfax of Leeds Castle, Lord Fairfax’s brother, visited Virginia and recorded his concern about how Lord Fairfax lived, and those thoughts almost certainly mirrored George William’s. Robert wrote that at Greenway Court the “House, Furniture, and Manner of Living is past all conception.” He claimed that there was “not a gentleman within sixty miles,” and that they were “surrounded by nothing but Buckskins, people that first settled here to kill deer for the sake of their skins, the most strange brutish people you ever saw.” The nearest town, Winchester, was full of “Dutch & Germans,” who were mostly “dissenters of different denominations,” while the “Established Church,” the true mark of British civilization, had only “one parson” to service five chapels in a county “a hundred miles long & forty broad.” Consequently, each chapel met “once in five weeks,” and “if the day proves Hot or Rainy, no parson.” These observations on life in the backcountry stood in stark contrast to the increasing gentility of Fairfax County.[25]

As the Fairfaxes’ enslaved workers unpacked the crates filled with furniture, textiles, wallpaper, architectural woodwork, and silver, Greenway Court could not have felt farther away. By 1763 Fairfax County was firmly established as home to the planter elite and was no longer the frontier that Colonel William Fairfax first encountered. The river towns of Alexandria, Colchester, and Dumfries offered taverns for entertainment and small shops stocked with necessary goods, while wealthy tobacco planters began to build large, highly refined houses around the county. House owners and guests looked to these houses and their furnishings as markers of social standing. These neighboring houses, such as George Mason’s Gunston Hall (1752), John Carlyle’s Alexandria house (1751), and George Washington’s Mount Vernon (expanded 1757–1759), formed the foundations of polite society. They were more than people’s homes; they were centers of hospitality where elite Virginians entertained their social equals through traditional rituals such as dinners, the taking of tea, and elaborate parties. Prior to leaving Britain, George William wrote home and ordered all of his father’s household furnishings sold to make way for the London goods he planned to buy. With the new goods they brought with them, the Fairfaxes sought to assert their standing at the height of colonial society and to draw Lord Fairfax back to live at Belvoir through a pair of rooms created for his own use: the Blue “Dressing Room” and the “Chintz Chamber.”[26]

Layout of Belvoir

While the furnishings for the rooms were exceptional for colonial Virginia, the floor plan and types of spaces at Belvoir were nearly all typical of those found in other homes of the Virginia gentry. The disposition of the rooms can be reconstructed using four specific pieces of evidence: a 1774 rental advertisement in the Virginia Gazette; archaeology; George William Fairfax’s 1773 inventory of the house; and Robert Stark’s 1763 wallpaper invoice. The advertisement describes the typical arrangement of rooms in a double-pile Virginia house, wherein the “lower Floor” consisted of “four convenient Rooms and a large Passage.” In large gentry houses, the second floor almost always had a floor plan similar to that of the first. At Belvoir, the floor plan is also reflected in the division of rooms found archaeologically in the cellar, which is often seen in brick dwellings (fig. 25). There are four rooms of uneven size, two on either side of a large passage. The question then remains, which room was which? While George William Fairfax did not mention the floors in his inventory of the house, he appears to have listed them in the order one encountered them in the house. The first four rooms—the dining room, the parlor, “Col. Fairfax’s D[ressin]g Room,” and “Mrs. Fairfax’s Chamber”—are listed before the remaining bedchambers and “The Dressing Chamber (see appendix).” Given typical Virginia practice, the first four rooms were almost certainly on the first floor (see fig. 7).[27]

The dimensions of the largest room, on the east, or river, front correspond with the measurements for a papier-mâché ceiling, purchased from Robert Stark along with “fine varnished Green” wallpaper for the space. Based on George William’s inventory, which lists twelve chairs, two card tables, and a sideboard table, this room—most likely the dining room—was the most heavily furnished space in Belvoir. The room also had three sets of window curtains, more than any other space on the first floor. The curtains were made of red moreen, the same fabric used to cover the chairs. Red and green were often used together during the period, making the moreen a logical choice to complement the green wallpaper provided by Stark. As in other Virginia dwellings, including Carlyle House, which Colonel William Fairfax’s son-in-law built on nearly the same floor plan as Belvoir, there was probably a division between public and private spaces delineated by the central passage. This suggests that Col. Fairfax’s Dressing Room and Mrs. Fairfax’s Chamber occupied the two rooms on the other (north) side of the central passage. The remaining space, probably the parlor, was on the south side of the house. Parlors diminished in importance in Virginia interiors as dining rooms took precedence. The parlor at Belvoir had only eight chairs, a spider-leg table, a dining table, and a few smaller items.[28]

On the second floor, the disposition of the five rooms—blue “Dressing Room,” “Red Chamber,” “Chintz Chamber,” “Yellow Chamber,” and an unknown space likely used as a lumber room—is more difficult to discern. According to George William’s inventory, the blue Dressing Room had three sets of window curtains and more furniture than any other space on the second floor. That number of windows and furnishings suggest that the blue dressing room either occupied room at the head of the stairs or the space above the dining room. The room likely functioned in tandem with an adjoining bedchamber, which was almost certainly the best bedchamber in the house, the “Chintz Chamber.” As decorative arts scholar John Cornforth has noted, these “best rooms” were places for entertaining or conducting business with the most important guests. This pair of spaces likely functioned as the domestic equivalent of “state rooms.” At the Governor’s Palace in Williamsburg, Lord Botetourt used two rooms on the second floor for a similar purpose. The room at the head of the stairs on the second floor served as his dressing room, while his bedchamber directly adjoined the space. The Governor’s Palace is the only other known instance of the use of such elaborate rooms in Virginia, a testament to the ostentation of these spaces at Belvoir. If the blue Dressing Chamber at Belvoir occupied the room at the head of the stairs and the “Chintz Chamber” occupied the large room beside it, perhaps the two remaining bedchambers, the “Red Chamber” and the “Yellow Chamber” occupied the two rooms on the east side of the house. The remaining room likely served as either a closet or a lumber room.[29]

Principal Entertaining Spaces

As with most Virginia great houses of the mid-eighteenth century, the principal entertaining spaces at Belvoir were the central passage, dining room, and parlor on the first floor. These spaces functioned in tandem and were almost always the most ornate rooms in the house. The central passage served as a room for social filtering and as one of the more important living spaces in the house. At Belvoir, the butler, who was likely one of the Fairfaxes’ enslaved people, opened the door for visitors and made the critical judgment of where to take them. For elite guests, the butler most often conducted them directly to the parlor, while those of lower rank remained in the passage where they would wait for the owner or another member of his family. The central passage also functioned as an informal living space because of the cross-breeze produced by opening the front and back doors. In such spaces, Virginia planters and their families often dressed more informally to take full advantage of the cooler air.[30]

At Belvoir, the passage was particularly spacious. There the Fairfaxes chose to imitate the stuccowork and stone entryways of grand English halls and entryways by installing “8 Pieces of Painted Stucco” wallpaper edged with “8 doz. borders.” As decorative arts scholar Margaret Pritchard suggests, “stucco papers” were likely printed architectural patterns painted en grisaille (fig. 26). Passages were often furnished with sets of chairs. The “14 Mahy. Marlborough Square Top Chairs [with] pin [cushion] seats” that Gomm and Son sold to the Fairfaxes for the room likely resembled the simple, square topped chairs illustrated in perspective in Thomas Chippendale’s Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker’s Director (fig. 27). Chairs of that basic design were popular in Virginia and Maryland and are represented by both locally made and imported seating. While the mahogany used for the Fairfaxes’ chairs conveyed elite status, the simple design of that seating alluded to the more casual nature of the passage. “Figured Showhair,” or horsehair, covered the slip seats, providing a resilient and easy-to-clean surface for chairs in constant use. While there were probably other objects in the space, such as old dining tables and possibly prints, the central passage or “The Passage below Stairs” is one of only three spaces whose furnishings are not listed in George William’s inventory (the others are a small room on the second floor and “The Lobby,” likely the second-floor stair hall).[31]

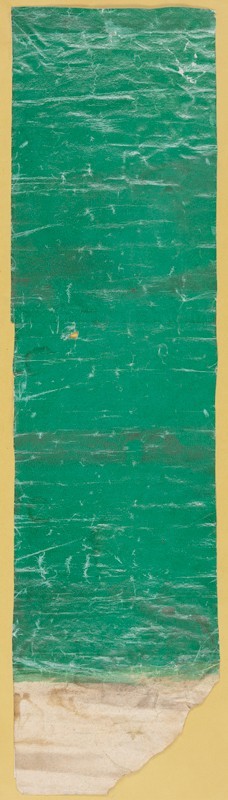

The dining room and parlor were the most formal spaces on the first floor, and entry required that a guest first pass through the central passage. By mid-century, dining rooms and parlors were often roughly equivalent in size and importance, representing the male and female spheres, respectively, but at Belvoir the dining room (20' 3" x 16' 5") was almost double the size of the parlor and was far more elaborate. For George William Fairfax, the dining room was the physical manifestation of his hospitality. There he presided over the table at dinner—the central social event of the day—and displayed the abundance of his estate through the many dishes of meat and vegetables arrayed on the table. He also exhibited his wealth through the many specialized accoutrements associated with meals: sets of spoons emblazoned with his crest, sets of English and Chinese ceramics, and sets of glassware for drinking. The room was one of the more architecturally elaborate in the house, with an entire ceiling covered in papier-mâché ornament; a chimneypiece likely consisting of a marble mantle with an ornamental frieze (a tablet flanked by appliques and trusses) surmounted by a carved wooden overmantle (an architrave with appliques or trusses and pediment with tablet, frieze, and central ornaments); “fine varnished Green” wall-paper; and upholstery and curtains in rich “Crimson morine” (fig. 28).[32]

The furniture in the room demonstrates that the space served multiple purposes. In the inventory, George William lists chairs, a sideboard, and a pair of card tables, indicating the room’s use for dining and entertaining—but there were no dining tables. The dining tables were likely kept in the passage when not in use and only brought in for meals in accordance with established English fashion. The twelve mahogany chairs were the most expensive examples with wooden backs in the house. The set was upholstered over-the-rail with brass nails and had loose covers made from “Rich Crimson Chiq.” The fixed and loose covers were made of wool and linen respectively which, fabrics that were durable, easy to clean, and were frequently used for dining chairs. The dining room also had the most expensive looking glass in the house, a “Large Sconce Glass the frame carvd & Gilt in Burnished Gold,” and a mahogany sideboard table “with fretwork upon the Edge of the Top, Astragal Mound[ing]s & Brackets.” The dining tables were likely standard English models with turned legs and pad feet or straight legs, but following British precedent. When not used for dining, the room served as a place for other forms of entertainment. When George William left for England in 1773, the dining room at Belvoir contained a pair of “Mahy. 3ft. [wide] Square Card Tables lind wth Green Cloth.” The tables were fairly simple, but they had “Astragal mouldings & open brackets” that may have matched those on the sideboard table. Complementing all of these furnishings was a large and costly “Wilton Persian Carpet,” a British copy of a Middle Eastern design (fig. 29).[33]

The parlor offered a less formal setting and was furnished more simply. During the middle of the eighteenth century, dining rooms and parlors were often interchangeable spaces. The Fairfaxes, who kept a dining table in the parlor, probably ate there frequently. That room was also furnished with a “Strong fine Mahy. Spider Leg Table” on which Sally almost certainly served tea, which was the sole purview of the lady of the house (figs. 30-31). The set of six chairs in that space was made of mahogany and “Covered over the rail wth. figured Horse hair & Brass naild.” Their individual value was less than that of the dining chairs listed in George William’s inventory. The most expensive seating in the parlor was the pair of “Mahy. Hollow Suff Back & Seat arm Chairs Coverd wth figured hair.” Likely resembling French elbow chairs, those objects were likely intended to differentiate the owners from their guests. The parlor does not appear to have had wallpaper, although it was furnished with a pair of curtains in Saxon green moreen with line and tassel to pull up in drapery. A silver hot water kettle, urn, and stand survives with the arms of Fairfax-impaling-Cary, which the couple likely used in this space (figs. 32-33). It is one of the more ornate extant examples of English rococo silver with a history in colonial America, a testament to the Faifaxes’ lavish lifestyle at Belvoir.[34]

Family Spaces

The private spaces, “Mrs. Fairfax’s Chamber” and “Col. Fairfax’s D[resin] g Room,” functioned in tandem and were the nexus of family life. In eighteenth-century Virginia, the bedchamber occupied by the owners was often located on the first floor and served as the domain of the lady of the house. From this room, she had a prime vantage point to the dining room, the kitchen, and domestic outbuildings, enabling her to manage the household affairs within her purview. Often these rooms had closets to store

linens, spices, and other valuable commodities, and the lady kept the key. The paucity of case furniture listed in George William’s inventory suggests that Belvoir had closets, although Mrs. Fairfax’s Chamber did contain a “Mahy. 3 ft. 9 in. Double Chest of Drawers with Square Ends.” That object, which is one of the few Fairfax pieces known, was probably for storage of Sally’s clothing and some of the household linens. Made of mahogany in the “neat and plain” taste, the chest’s high quality locks would have kept expensive textiles secure. The chest has George William’s cipher “GEFx” and the shipping crate numbers painted on the back, markings which correspond with notes in the Fairfax account book (figs. 34-37).[35]

As in most eighteenth-century bedchambers, the bed with its expensive textiles was the most valuable object in the room. Mrs. Fairfax’s chamber housed the least expensive bed in the house: the “four post” bed with curtains made from “Saxon Green 1/2 In[c]h Chique [sic]” from Gomm and Son. The bedstead was probably made from an inexpensive conifer, and its hangings were most likely linen, one of the less expensive fibers available, with little to no trim aside from a stitched edge. “Saxon green” was a newly fashionable emerald color made by boiling a textile dyed Saxon blue in fustic. A set of four “Mahy. Square Top Chairs” similar to those in the central passage accompanied the bed, making the room suitable for entertaining close friends and family. The seats of the chairs were covered in canvas and were among the less expensive seating listed in George William’s inventory. “Cases,” or slipcovers, made of the same Saxon green linen check as the bed hangings and a single festooned window curtain furnished by Gomm and Son made the bedroom ensemble appear en suite. The dressing table listed in the 1773 inventory does not correspond to any object on the Gomm invoice, but it was one of the more expensive objects in Belvoir.[36]

Col. Fairfax’s Dressing Room served as a study and his center of operations in the house. In the period, Virginia men occasionally had dedicated studies, but most often they simply used a desk set up in the dining room. At Belvoir, George William elevated the standing of his study by calling it his dressing room. It was a place for conducting business, entertaining guests, storing his clothing, and dressing, which he likely accomplished with the assistance of an enslaved valet. Belvoir had a separate office for the proprietary outside the house. George William’s study was more lavishly furnished than Mrs. Fairfax’s chamber, containing the most expensive piece of case furniture in the house: a “Mahy 3 ft. 6 Inh. [wide] Desk” surmounted by a “Bookcase wth. pidement head,” “Gilt Ornaments” on the frieze, and doors “wired wth. Green Silk behind.” That object was where George William housed his personal correspondence and business accounts. His study also contained “A Mahy. Shaveing Table & Glass” (figs. 38-40), a set of four mahogany chairs, and a mahogany “Settea bedstead,” which was a standard settee that opened up to form a bed large enough for one person (figs. 41-42). The bed was probably intended for George William’s use when his wife was ill, but it could also have been used to create an extra bedchamber when there was a surplus of visitors. The chairs were slightly more elaborate than those in Mrs. Fairfax’s chamber, indicating the space’s more public nature. The Gomms covered their pincushion, or slip, seats and the settee bed with “Green morine,” a worsted wool cloth often with a waved or stamped finish. The fabric was more expensive than linen. The entire suite of seating furniture also received loose covers of Saxon green check to protect the morine from light and dirt.[37]

Upstairs Bedchambers

In keeping with English custom, guests at Belvoir were assigned bedchambers based on their social station; the more important the visitor, the more elaborate the room. The differences among the bedchambers were often subtle, but they would have been readily apparent to the Fairfaxes’ guests, who would have recognized variations in the furniture, upholstery, bed hangings, and window treatments. At Belvoir, the best bedroom was the “Chintz Chamber,” distinguished by having curtains and bed hangings made from one of the more valuable textiles in the house. The textiles most likely to have been described as “chintz” were a multi-colored, printed and hand-painted Indian cotton, an English derivative, or an English or European printed copper plate design. The same material was used to make slipcovers for the four backstools in that bedchamber, which are valued higher than any of the bedchamber side chairs in George William’s inventory. Second in the hierarchy of sleeping rooms was the “Yellow Chamber,” which had window curtains, bed hangings, and slip covers for four mahogany side chairs made of “yellow morine.” That textile was less expensive than printed chintz but costlier than linen check. The bed was made of mahogany, with “fluted Pillars” and a “carvd cornice.” Although it is possible that all of the posts were fluted, those at the head of the bed were most likely plain. A pair of Wilton bedside carpets and a “Wilton Persian Carpet,” enhanced the comfort of the space, but only the chintz and yellow bedchambers had carpeting. The “Red Chamber” held the third rank, with simple bed hangings of red check. The bedstead was likely made of an inexpensive wood and had no cornice, while the mahogany chairs were worth one shilling more per chair than those in Mrs. Fairfax’s chamber. Like those chairs, the Gomms covered the mahogany chairs in canvas and provided them with slipcovers in the same material used on the bed.[38]

Ceremonial Spaces

The blue “Dressing Chamber” and “Chintz Chamber” in Belvoir were anomalies in eighteenth-century Virginia houses. The pair of spaces functioned as state rooms, or “best rooms,” reserved for the use of the Fairfaxes’ most important visitors. At Belvoir, George William and Sally Fairfax almost certainly intended these rooms as accommodations for Lord Fairfax, and they hoped that their creation would entice him to move permanently to Belvoir. In England, gentlemen of rank often created such spaces for themselves, along with a more elaborate room or suite of rooms to accommodate royalty or visitors whose social status exceeded that of the estate’s owner. In the most elevated settings, state rooms often consisted of an enfilade of spaces approaching the bedchamber of the king or the aristocrat. In this arrangement, the two most important spaces were the bedchamber and the dressing room. In the morning, the room’s resident would rise in the bedchamber, where his valets dressed him in the company of his highest ranking guests. He then proceeded to the dressing chamber to hold a levee, a formal ceremony in which his valets applied the final touches to his outfit and wig while he sat at a dressing table. During the levee, the gentleman conducted the business of the day. According to Isaac Ware, the “dressing-room in the house of a person of fashion” was essential “for its natural use in being the place for dressing, but [also] for the several persons who are seen there.” Mornings were often reserved “for dispatching business.” Because men of rank were “not supposed to wait” for those of lower station, the latter were given “orders to come about a certain hour” and admitted while the former were dressing.[39]

Although Ware spoke to an audience of wealthy men and women beyond the aristocracy, such spaces are only known to have been used by aristocrats in colonial Virginia. George William attempted to transplant the trappings of the English landed elite to the colonies, where there was little appetite for such elevated spaces. The Belvoir suite is only the second recorded example of such an elaborate dressing room/chamber combination; the other belonged to Lord Botetourt, the royal governor of Virginia. The presence of such a space at Belvoir is a testament to the important position George William believed Lord Fairfax occupied in Virginia, and Ware’s description must have encapsulated the former’s vision of the way a man of Lord Fairfax’s stature should conduct business in the colonies. As such, the arrangement and furnishings of the “Dressing Chamber” and “Chintz Chamber” rooms can be interpreted as “state rooms” and as a criticism of Lord Fairfax’s casual lifestyle on the Virginia frontier. There can be little doubt that George William also intended to use these rooms when he acceded to his cousin’s title at Lord Fairfax’s death. As a man forced to live a frugal existence at an early age, Lord Fairfax seems to have chafed at the ostentation of these spaces, further dividing the two men.

The elaborate nature of the furniture and the color of the textiles and wallpaper made the dressing chamber visually striking. The room contained “8 Mahy. Marlboroug Stuff back Chairs” (backstools) and a “Large Sofa,” one of the earliest documented in the Tidewater region. Backstools and sofas were among the more expensive seating purchased by colonists, and their use was typically reserved for the finest rooms. Examples from only three sets with Virginia histories are known. One set belonged to Robert Beverly of Blandfield in Essex County, one to William Byrd III of Westover in Charles City County, and one to the colonial government. Backstools introduced a level of comfort previously unseen in colonial Virginia, where chairs with wooden backs were the norm and easy chairs were expensive anomalies. Settees and sofas were even scarcer. A settee that descended in the Page family of Rosewell in Essex County survives, but no extant sofa with a colonial Virginia history is known. While couches with one arm and an open back were common, it remains unclear why sofas do not appear in Virginia inventories until the 1790s. The form was popular in the mid-Atlantic and northern colonies, as both imported and locally made examples attest. Perhaps, the reluctance to adopt such forms relates to the new, more relaxed style of seating that sofas introduced. As John Singleton Copley’s portrait of an unknown lady demonstrates, sofas allowed sitters to relax and sink into the upholstery and strike a less formal, and even scandalous, pose than previous furniture forms allowed (fig. 43). Commentators and satirists in England and France remarked on the dangers posed by the new form, whose comfort might encourage one to spend the day relaxing in its cushions rather than applying oneself to productive pursuits. Regardless of the reason for their typical absence, the presence of this sofa further highlighted the aristocratic nature of the space. Among the other lavish furnishings were an “India Skreen,” a “Compass Japannd Dressing Glass,” a “Large Ovall Glass” with a mahogany frame “painted lead white,” a large looking glass, and a pair of “Girandoles” with “single branches.” The looking glass may have been flanked by the girandoles and hung over the sofa, an arrangement common during the period (fig. 19). Underfoot, the Fairfaxes placed the largest carpet, which was likely a Wilton, given its high value.[40]

Textiles accounted for much of the expense of backstools and sofas. An ordinary side chair might require a little more than half a yard of fabric to cover a slip seat, while a backstool required approximately two yards of show fabric for the front and another yard of the same fabric or a less expensive textile for the back. Sofas required even larger amounts. The labor involved in upholstering backstools and sofas also contributed to their cost. Both forms required a base layer of webbing before the application of multiple layers of grass and horsehair, which were stitched between linen or coarser buckram. The craftsman who upholstered the Fairfaxes’ backstools described those objects as “Mahy. Marlboroug Stuff back chairs stuffd in the best French manner.” The “French manner” referred to the square, or boxed, shape of the seat and back. “Round Stuffed” chairs, like those provided for the Chintz Chamber, were less labor-intensive. The blue Dressing Room chairs were “cush[ion]ed,” a term suggesting higher padding, and “Borderd & wilted,” meaning that the seat sides were covered with a fabric panel different from that on the top and finished with a narrow welt at the seams. The upholsterer ornamented the show cloth with “2 Rows [of] No. 3” polished brass nails. The sofa was made “to match” and included “2 bolsters.” Because no separate mattress or cushions are mentioned, the piece likely had a seat built up with horsehair like that on the chairs and had an overstuffed back. Sixty-seven yards of “Superf[in]e. Saxon Blew Mixd Damask” were used to upholster this seating and fabricate the three window curtains, which were trimmed with “the best silk Cover’d Lace” (tape) and fringe and fitted with “6 Silk & worsted Tassells” and cords so they could be drawn up in drapery. The chairs and sofa also received loose covers of “Superf[in]e Saxon Blew In[ch]. Chiq.,” likely made of linen.[41]