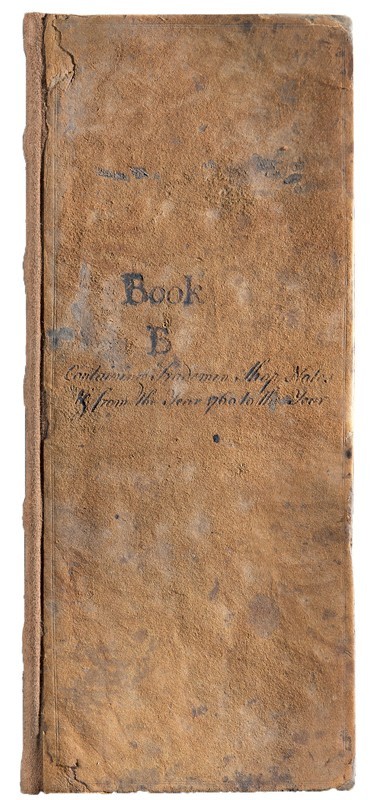

William Fairfax and George William Fairfax Account Book, 1742, 1748, 1760–1772. Account book B kept by George William Fairfax “Containing Tradesmen Shop Notes & c from the Year 1760 to the Year [1772].” (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

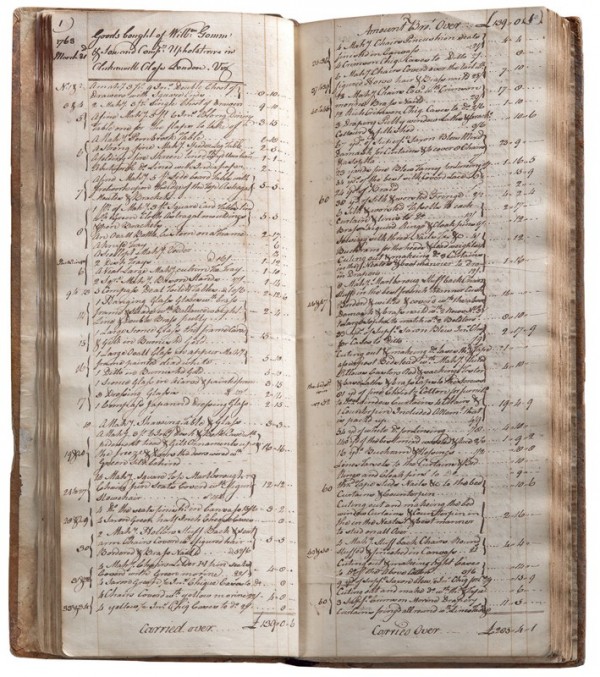

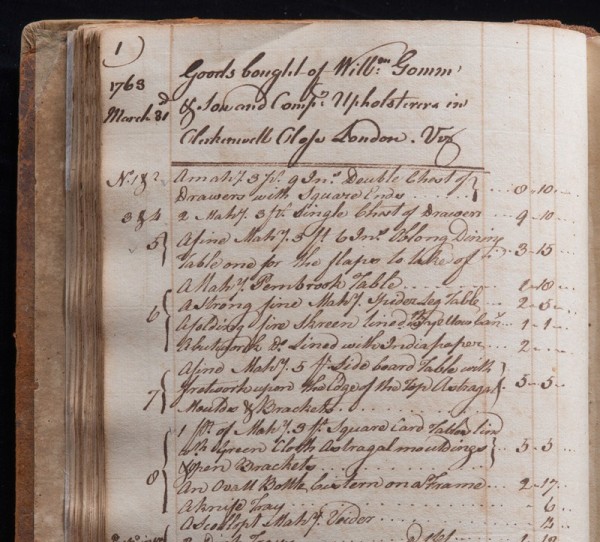

Invoice for furniture and upholstered goods purchased by George William Fairfax from the London firm William Gomm and Son and Company on March 31, 1763, on pp. 1–2 in George William Fairfax’s account book. (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The goods are listed with their prices on the right and the numbers of their shipping crates on the left.

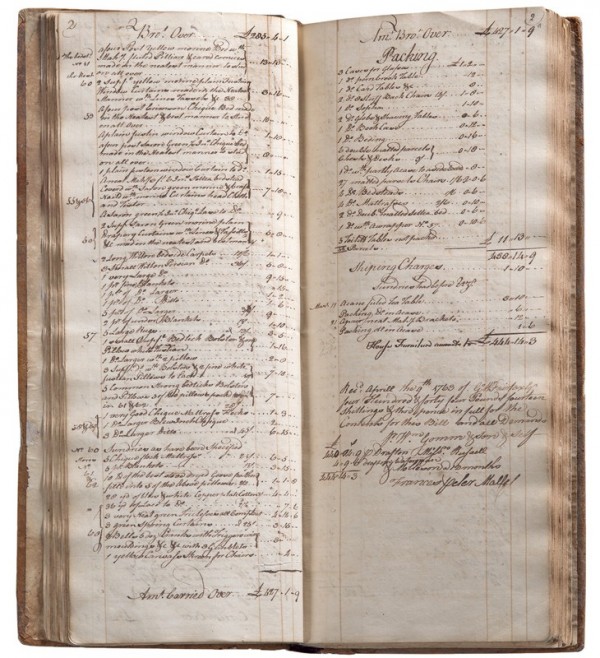

Invoice for furniture and upholstered goods purchased by George William Fairfax from William Gomm and Son and Company on March 31, 1763, on pp. 3–4 in George William Fairfax’s account book. (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Chimney back, Marlboro Furnace, Frederick County, Virginia, ca. 1770. Cast iron. 34 1/2" x 31". (Courtesy, United States Army Engineer Museum, Fort Belvoir, Virginia; photo, Robert Hinds.) Thomas, 6th Lord Fairfax commissioned a set of chimney backs, represented by this example, for his home at Greenway Court in Clarke County, Virginia. The arms are those of Fairfax, featuring a lion rampant, impaling Culpeper, featuring a bend or diagonal stripe. The Culpeper arms are those of Lord Fairfax’s mother, Catherine, Lady Culpeper, the heir to the Northern Neck Proprietary.

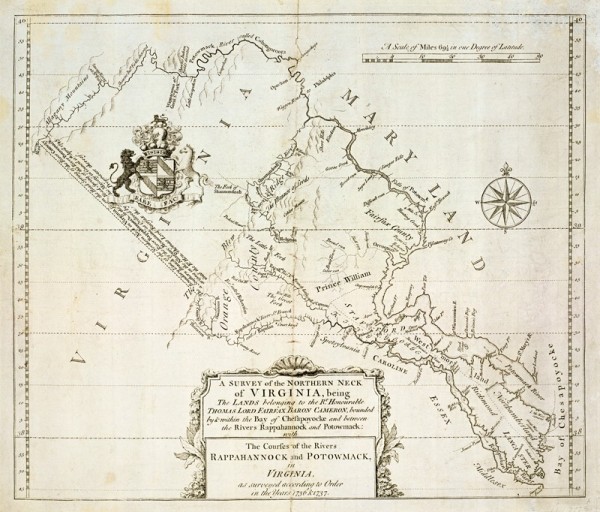

John Warner, A Survey of the Northern Neck of Virginia, being the lands belonging to the R.t. Honourable Thomas Lord Fairfax Baron Cameron, bounded by & within the BAY of Chesapoyocke and between the Rivers Rappahannock and Potowmack, in Virginia (London, 1745). 12" x 14". Engraving on paper. (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.) According to the terms of the Northern Neck grant, Lord Fairfax owned all of the land between the Rappahannock and Potomac Rivers, a claim disputed by Virginia’s colonial government. Fairfax requested that the Privy Council resolve the dispute, and the two sides employed surveyors to determine the bounds in 1736 and 1737. The Privy Council ruled in Lord Fairfax’s favor in 1745, leaving him with more than five million acres of land.

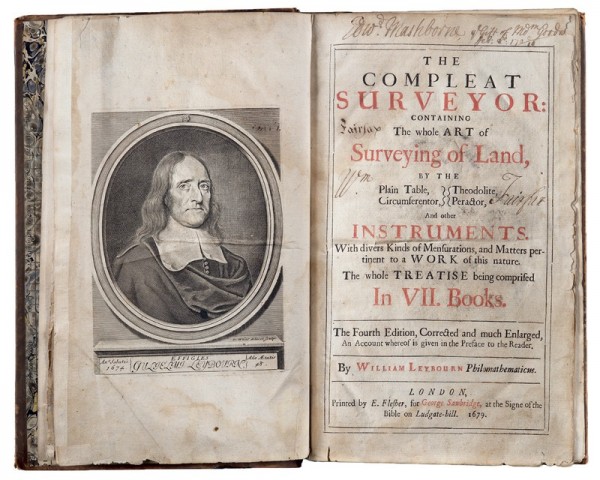

Title page of William Leybourn, The Compleat Surveyor (London, 1679). (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This book contains Colonel William Fairfax’s youthful signature, indicating that he likely learned the art of surveying using this copy. The Fairfaxes lent this book to George Washington, and he too likely used it to learn surveying as he began his career surveying for Lord Fairfax.

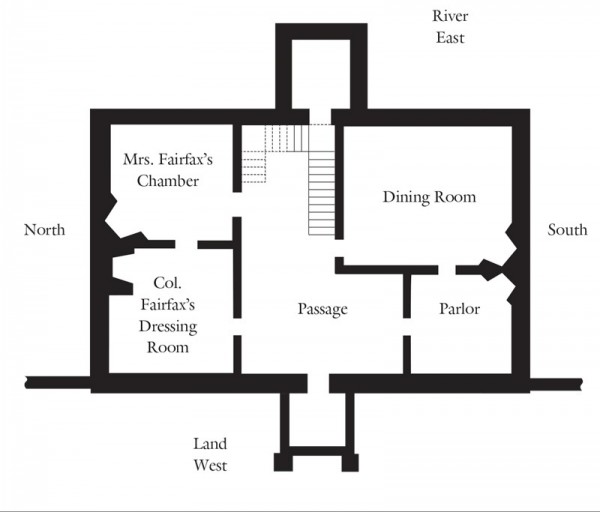

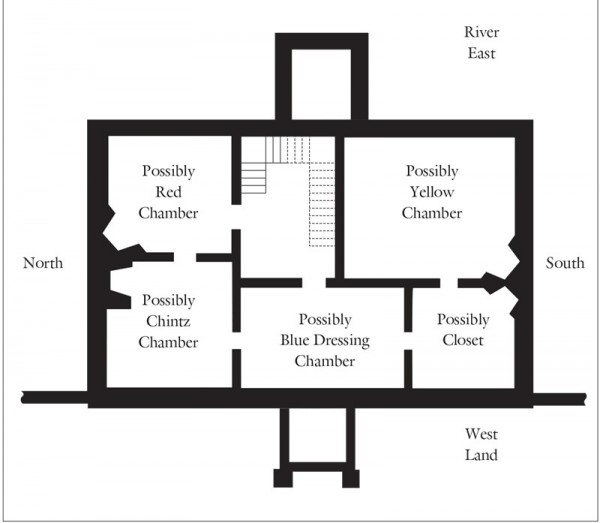

Conjectural first-floor plan of Belvoir, ca. 1740–1763, reflecting changes made by George William and Sally Fairfax in 1763.

Anne Byrd Carter, attributed to William Dering, probably Charles City County, Virginia, 1742–1746. Oil on canvas. 50 1/2" x 40". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.) The garden setting, likely at Westover in Charles City County, Virginia, closely resembles that found archaeologically at Belvoir.

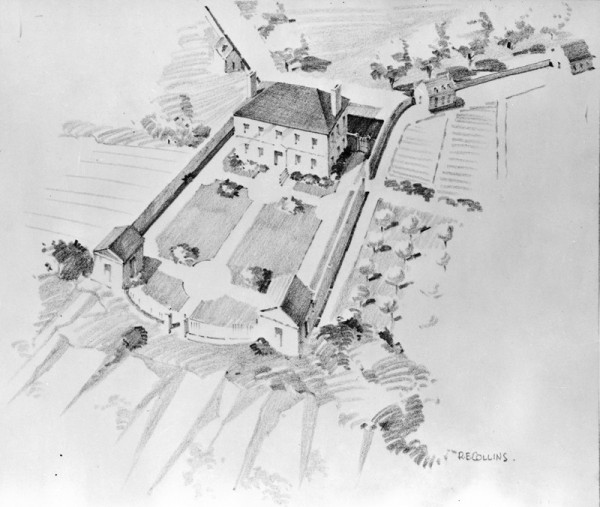

R. E. Collins, conjectural view of Belvoir and gardens, 1940–1950. (Courtesy, Library of Congress.) While fanciful, this drawing illustrates the major features of Belvoir as found archaeologically. The garden had a central pathway, but the remaining divisions are conjectural.

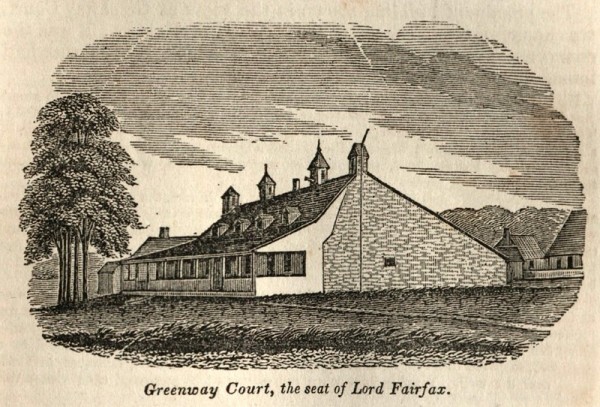

Greenway Court, Clarke County (formerly part of Frederick County), Virginia, illustrated in Henry Howe, Historical Collections of Virginia (Charleston, S.C.: S. C. Babcock and Co., 1845), p. 235. (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association.) Lord Fairfax lived at Greenway Court with his nephew Thomas Bryan Martin. The roof collapsed in 1834, and the house was torn down.

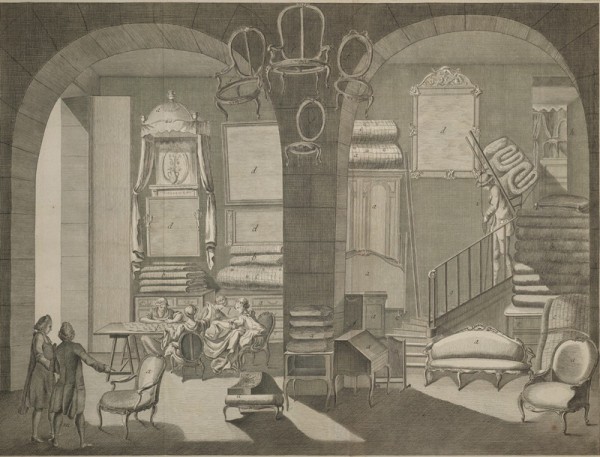

Robert Bénard, after Radel, Tapissier. Intérieur d’une boutique et differens ouvrages, plate 1, Encyclopédie, planches, sur les sciences, les arts libéraux, et les arts méchaniques, avec leur explication, vol. 9, edited by Denis Diderot et al. (Paris: Chez Briasson, 1762–1772). Engraving. 18 45/64" x 13 31/32". (Courtesy, Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts, University of Pennsylvania.) Many aspects of the upholsterer’s trade appear in this French engraving, including: case furniture, chair frames, upholstered seating, looking glasses, and mattresses for bedding.

Newcastle House, Clerkenwell Close, London, illustrated in William J. Pinks, The History of Clerkenwell, edited by Edward J. Wood (London: J. T. Pickburn, 1865), p. 97. (Courtesy, British Library.)

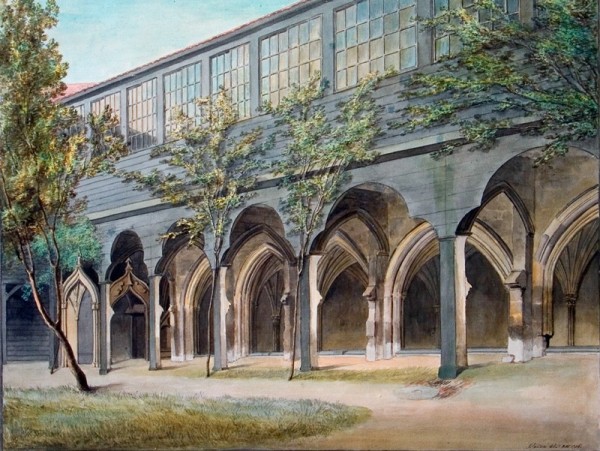

J. Sanders, Gomm and Company warerooms, Old St. James’s Church, Clerkenwell Close, London, 1786. (Courtesy, Society of Antiquaries.) Gomm and Company built its warerooms with continuous north-facing windows atop the south cloister of Old St. James’s Church. The “Gothick” arcade incorporates trefoils to harmonize with the style of the cloister. The firm sold furniture with gothic arches similar to those seen on the ground floor of their warerooms.

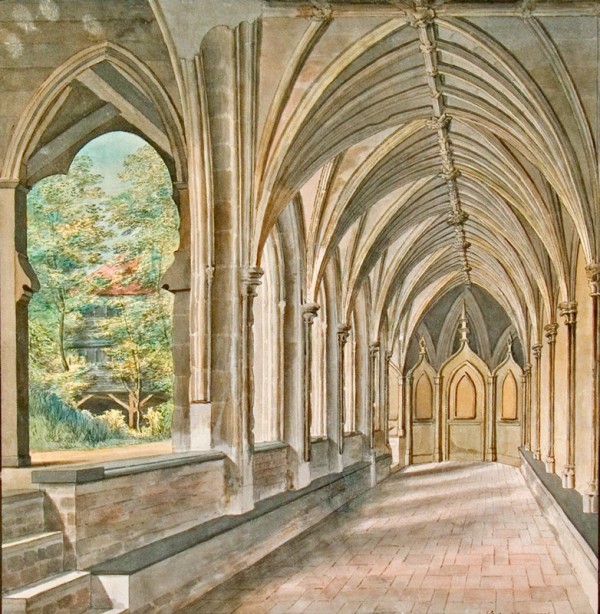

J. Sanders, Old St. James’s Church, remains of the south cloister, Clerkenwell Close, London, 1786. (Courtesy, Society of Antiquaries.) Gomm and Company added the “Gothick” screen at the end of the arcade.

Gomm and Company workrooms, Nuns’ Hall, Clerkenwell Close, London, illustrated in James Charles Crowle’s edition of Thomas Pennant, Some Account of London (London: Robert Faulder, 1793). (Courtesy, British Museum.) Gomm and Company built its work rooms atop the medieval remains of Nuns’ Hall.

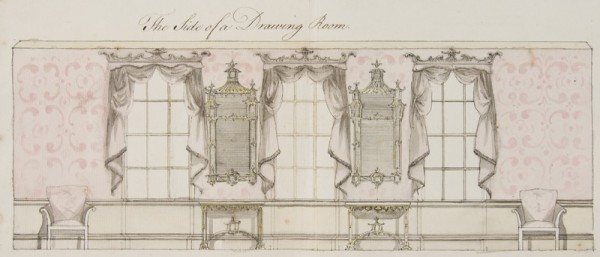

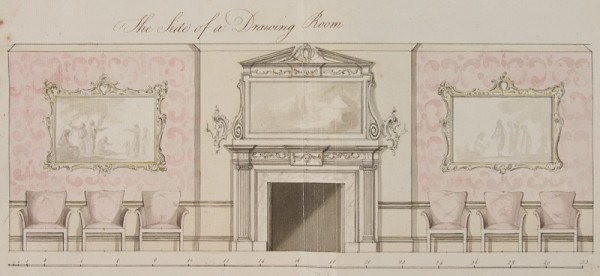

William Gomm, The Side of a Drawing Room, London, 1761. Ink and watercolor on paper. 7 3/4" x 15 3/4". (Courtesy, Winterthur Library, Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera.) Gomm’s depictions of four elevations of a room were probably for a potential client. The drawings demonstrate his knowledge of the latest design books, his ability to create new elements, and his capacity to furnish a room tastefully in its entirety.

William Gomm, The Side of a Drawing Room, London, 1761. Ink and watercolor on paper. 8 1/4" x 16". (Courtesy, Winterthur Library, Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera.)

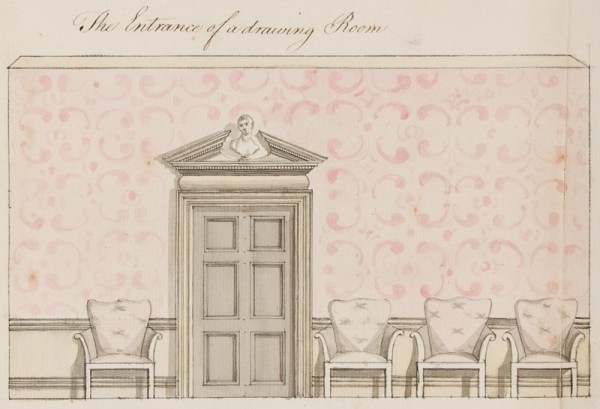

William Gomm, The Entrance of a Drawing Room, London, 1761. Ink and watercolor on paper. 7" x 10 1/2". (Courtesy, Winterthur Library, Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera.)

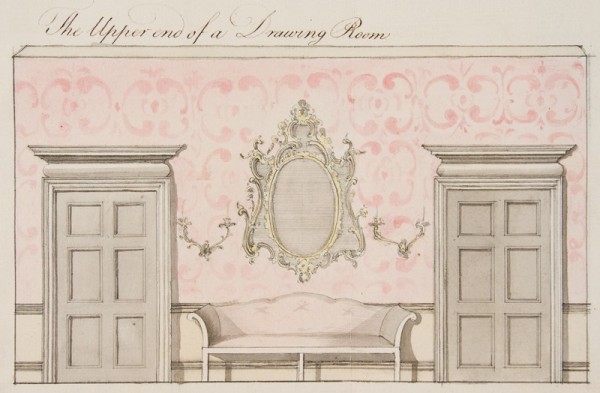

William Gomm, The Upper End of a Drawing Room, London, 1761. Ink and watercolor on paper. 7 1/4" x 11 1/4". (Courtesy, Winterthur Library, Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera.) English designers often created a focal wall in a room utilizing a sofa, candle branches, and looking glasses or pictures.

William Gomm, A Cloath’s Press, London, July 18, 1761. Ink and watercolor on paper. 8 3/4" x 8 1/4". (Courtesy, Winterthur Library, Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera.) The primary output of the Gomm firm was likely neat and plain pieces like this clothes press.

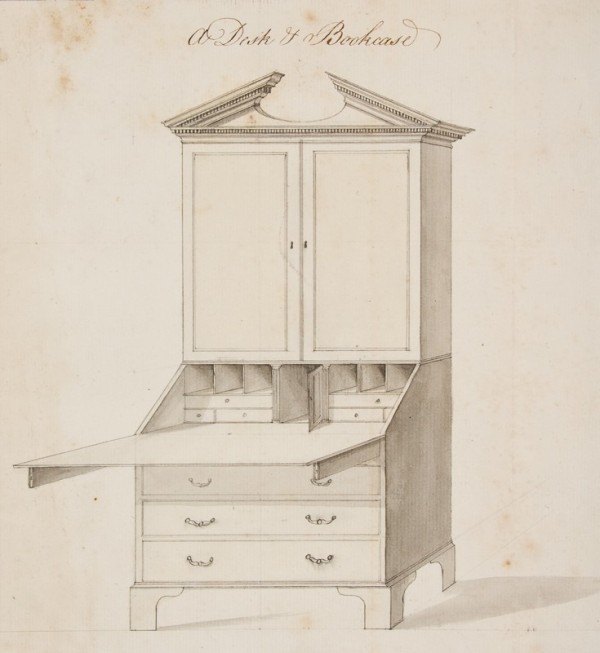

William Gomm, A Desk & Bookcase, London, August 15, 1761. Ink and watercolor on paper. 10 3/4" x 9 3/4". (Courtesy, Winterthur Library, Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera.)

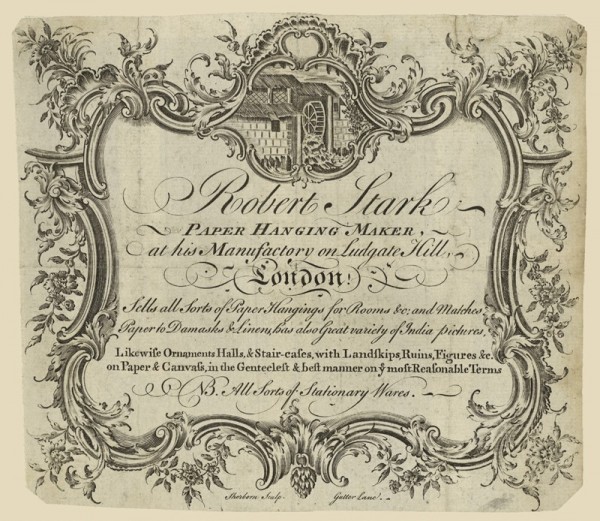

Thomas Sherborn, trade card for Robert Stark, London, ca. 1765. Creative Commons © Trustees of the British Museum.

Papier-mâché ceiling in the first-floor, southeast parlor of Philipse Manor, Yonkers, New York, ca. 1750. (Courtesy, Philipse Manor Hall State Historic Site, administered by the New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation; photo, Steven Spandle.)

Greenway Court Land Office, Clarke County, Virginia. (Courtesy, Dennis Pogue.)

Conjectural second-floor plan of Belvoir, 1763–1783.

An Interior with Members of a Family, attributed to Strickland Lowry, Ireland, ca. 1770s. Oil on canvas. 25" x 30" (Courtesy, National Gallery of Ireland.) The architectural wallpaper printed en grisaille is one of a number of patterns that could have been called “Painted Stucco.” The “Square Top Chairs” are likely similar to those in the central passage and Mrs. Fairfax’s chamber at Belvoir.

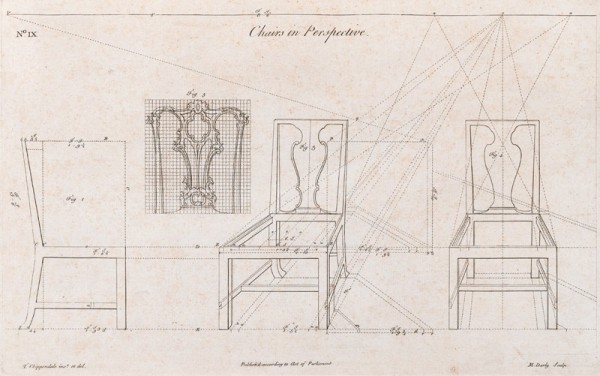

Chairs in perspective illustrated on pl. 9 in Thomas Chippendale, The Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker’s Director (London, 1754). (Courtesy, Winterthur Library, Printed Book and Periodical Collection.)

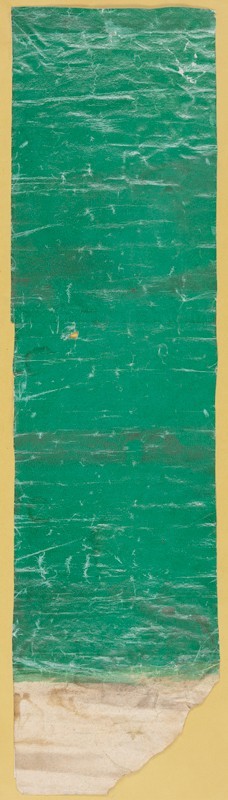

Wallpaper fragment recovered at Captain Lord Mansion, Kennebunkport, Maine, 1790–1810. Paint and polish or varnish on paper. (Courtesy, Historic New England.)

Johan Zoffany, Sir Lawrence Dundas with His Grandson, England, 1769–1770. Oil on canvas. 40" x 50" (Courtesy, Zetland Collection.) The carpet depicted by Zoffany would have been called a “Wilton Persian carpet” in the eighteenth century. Carpets of that type were based on Middle Eastern designs.

Spider-leg table, England, 1750–1770. Mahogany with mahogany and unidentified conifer. H. 27 1/2", W. 28", D. 26 7/8". (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

View showing the spider-leg table illustrated in fig. 30 with swing legs retracted and leaves down. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Samuel Courtauld, kettle, burner, and stand, London, 1753. Silver and rattan. H. 15 1/2", W. 11 1/8", D. 7 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This kettle is one of the more ornate pieces of English rococo silver with a history in colonial America. It is engraved with the coat of arms of Fairfax impaling Cary for George William Fairfax and Sarah (Sally) Cary.

Detail of the coat of arms on the kettle, burner, and stand illustrated in fig. 32. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

William Gomm and Company, chest-on-chest, London, 1763. Mahogany with oak and an unidentified conifer. H. 72 1/2", W. 46 1/4", D. 26" (Courtesy, Tudor Place Historic House and Garden; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

The back of the chest-on-chest illustrated in fig. 34, showing the stenciled ciphers “GWFx” and painted crate numbers. (Courtesy, Tudor Place Historic House and Garden; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The top case is marked “No. 2” and the bottom case is marked “No. 1,” designating the crates in which the pieces were shipped.

Detail of the back of the of chest-on-chest illustrated in fig. 34 showing the stenciled cipher “GWFx” and painted crate number “No. 2.” (Courtesy, Tudor Place Historic House and Garden; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

William Fairfax and George William Fairfax Account Book, 1742, 1748, 1760–1772. (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The account entry is for the double chest of drawers illustrated in figs. 34–36 along with crate numbers listed on the left.

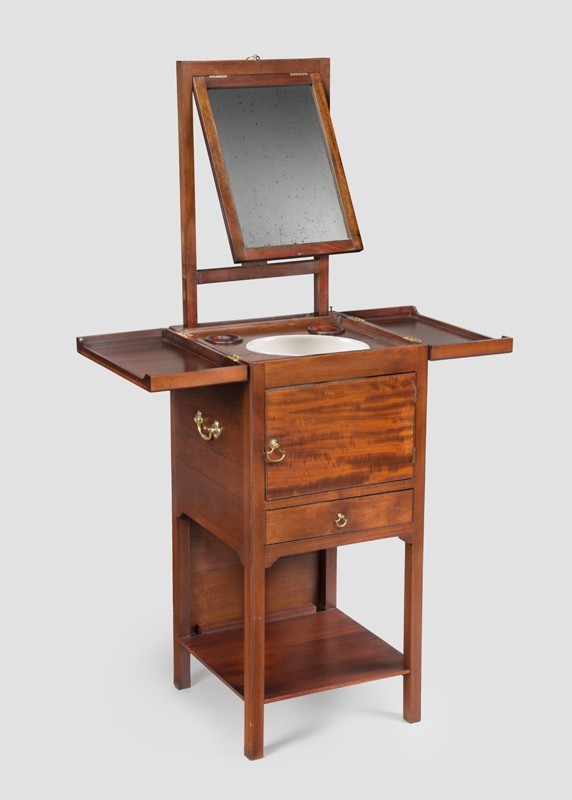

William Gomm and Company, shaving desk, London, 1763. Mahogany with oak and an unidentified conifer. H. 33 1/4", W. 15 1/2", D. 15 1/2" (closed). (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Open view of the shaving desk illustrated in fig. 38. (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The lid and shelf are restored.

Open and expanded view of the shaving desk illustrated in fig. 38. (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The outer frame is original, with mortices indicating the positions of the mirror and the central brace.

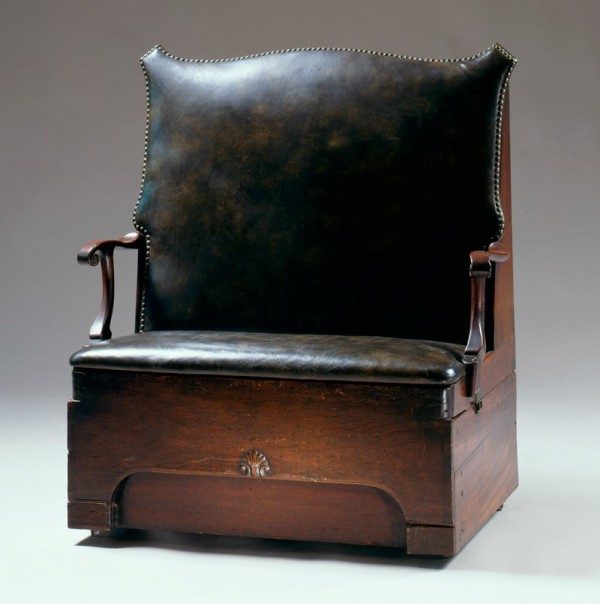

Settee bedstead, England, 1760–1780. Mahogany with beech; leather, wool, linen, brass, iron. H. 49 1/2", W. 40 7/8", D. 28 1/4" (closed). (Courtesy, Sotheby’s.)

Open view of the settee bedstead illustrated in fig. 41. (Courtesy, Sotheby’s.) The curtains slide on an iron compass rod that is bent into a square, obviating the need for three separate curtains and keeping more heat inside. This feature occurs frequently on beds where the compass rod extends around the outside of the footposts and beneath the cornice.

John Singleton Copley, Portrait of a Lady, probably Boston, Massachusetts, 1771. Oil on canvas. 50" x 40". (Courtesy, Los Angeles County Museum of Art.)

Papier-mâché wallpaper border, England, ca. 1765. (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.) This fragment was found in Governor John Wentworth’s house in Portsmouth, New Hampshire.

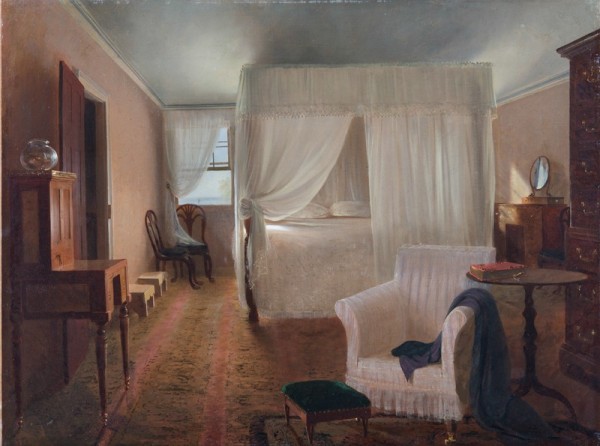

John Gadsby Chapman, The Bed Chamber of Washington, in Which he Died with all the Furniture as it Was at the Time. Drawn on the Spot by Permission of Mrs. John Washington of Mount Vernon, Virginia, 1835. Oil on canvas. 21 9/16" x 29". (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The artist depicted the Washingtons’ Philadelphia-made three-rod bed. The rods are positioned between the bedpost just below the cornice, and the curtains hang from metal rings. This was a common and inexpensive treatment in the period. The chest-on-chest in the right corner is illustrated in fig. 34.

Reproduction bed in the chintz chamber in Mount Vernon, Mount Vernon, Virginia. (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association; photo, Matthew Briney.) This bed is a conjectural reproduction of the chintz bed with drapery curtains George Washington purchased from Philadelphia upholsterer John Ross in 1773. The drapery curtains are tacked to the cornice and raised and lowered with line secured to brass rings on a pulley system installed in the cornice. This type of bed was the most expensive and complicated in the period.

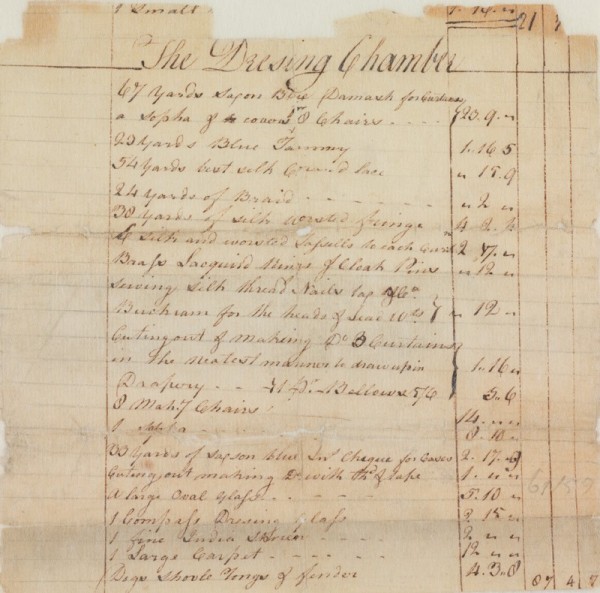

“The Dressing Chamber” from George William Fairfax’s inventory of Belvoir, 1773. (Courtesy, Virginia Museum of History and Culture.)

John Watts, pewter hot water plates, London, ca. 1765. Pewter. H. 97/16", W.113/16", D. 17/8". (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) These may be three of the “10 Pewter Water plates” Washington purchased at the Belvoir auction along with other kitchen items.

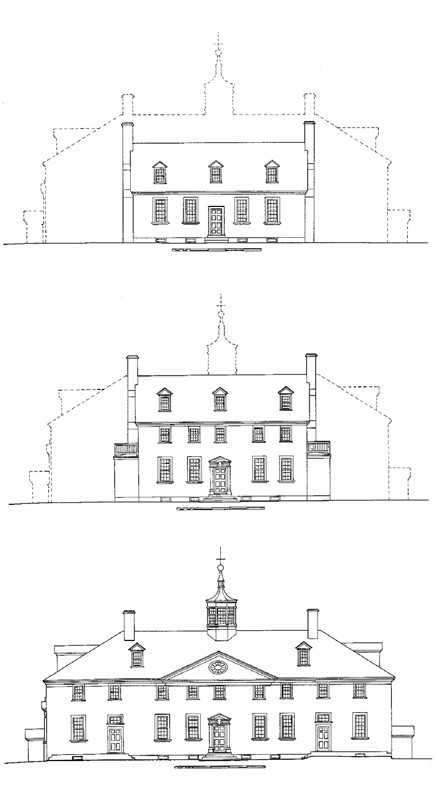

Mount Vernon, Mount Vernon, Virginia, 1734–1787. (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association.) George Washington expanded Mount Vernon, the house his father built in 1734, twice. He first added a second story and a garret between 1757 and 1759. Then, in 1774 George began building two wings, a project he completed in 1787. (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association.)

Charles Willson Peale, Colonel George Washington, Virginia , 1772. Oil on canvas. 50" x 40". (Courtesy, Washington-Custis-Lee Collection, Washington and Lee University, Lexington, Virginia.)

Charles Willson Peale, Martha Washington, Virginia, 1772; refashioned ca. 1790. Watercolor on ivory, gold, copper alloy, glass. 2 3/8" x 1 13/16". (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

“Small Dining Room” at Mount Vernon, Mount Vernon, Virginia. (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association; photo, Walter Smalling.)

William Bernard Sears and anonymous “stucco man,” chimneypiece in the “Small Dining Room,” Mount Vernon, 1774. (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Sideboard table, England, 1740–1757. Black walnut; marble. H. 29 7/8", W. 28 1/4" D. 25 7/8". (Courtesy Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The knee blocks are missing.

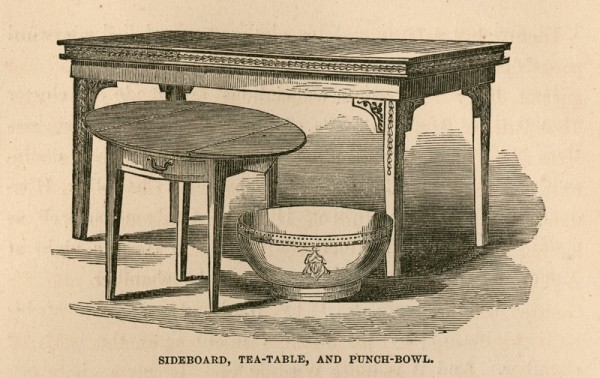

Sideboard table, Pembroke table, and punch bowl illustrated in Benson J. Lossing, Mount Vernon and Its Associations: Historical, Biographical, and Pictorial (New York: W. A. Townsend and Company, 1859), p. 317. The author illustrated the Fairfax sideboard when it was at Arlington House, but his depictions are only partially accurate. Gomm and Company’s invoice notes that the sideboard table they provided had no inlay.

Reconstruction (1952) of the bottle cistern William Gomm and Company furnished for George William and Sally Fairfax in 1763. Mahogany; lead, brass. H. 18 3/8" x W. 23" D. 21 1/4". (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The brass bands, the lion mask handles, and the staves to which the handles are attached are the only surviving components of the “Ovall Bottle Cistern on a Frame” George Washington purchased from George William Fairfax.

George Washington’s study, Mount Vernon, Mount Vernon, Virginia. (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association; photo, Robert Lautman.) George Washington added the built-in bookcase in 1786.

Front parlor, Mount Vernon, Mount Vernon, Virginia. (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The front parlor sofa, chairs, and window curtains are recreated utilizing the documentary evidence provided by the Fairfax account book and comparison with surviving period pieces with similar features.

Front parlor, Mount Vernon, Mount Vernon, Virginia. (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Guests arrived through the central passage visible in the distance.

Front parlor, Mount Vernon, Mount Vernon, Virginia. (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The front parlor became the formal entry to the two-story New Room visible through the doorway.

New Room, Mount Vernon, Mount Vernon, Virginia. (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

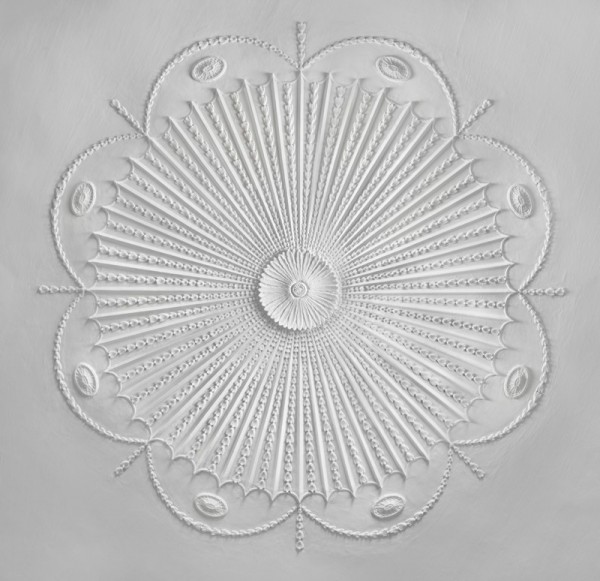

Richard Tharpe for John Rawlins, front parlor ceiling, Mount Vernon, Mount Vernon, Virginia, 1787. (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) George Washington updated the ceiling with neoclassical ornament to unite the space visually with the New Room.