The author examining green‑glazed ceramics at the Independence National Historical Park Archaeology Laboratory in 2018. (Photo, Robert Hunter.)

Coffeepot, attributed to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1807–1820. Philadelphia queensware with engine-turned decoration. H. 9". (Private collection; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Miniature portrait, David G. Seixas, attributed to John Carlin. Watercolor on ivory. (Courtesy, Pennsylvania School for the Deaf.)

Plate, Enoch Wood & Sons, Burslem, Staffordshire, England, ca. 1818–1848. Whiteware. D. 8 1/2". (Collection of the author; photo, Robert Hunter.) Transfer-printed image depicting the Philadelphia Asylum for the Deaf and Dumb, now the Pennsylvania School for the Deaf, ca. 1824.

Dish, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1770s. Slipware with green copper-oxide highlights. D. 11 3/4". (Courtesy, National Park Service, Independence National Historical Park, Inde-57214.)

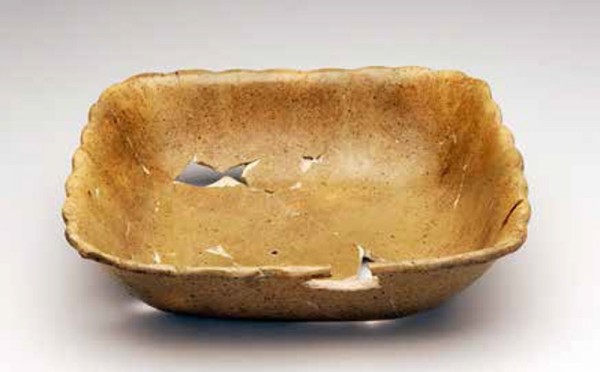

Dish, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1810–1820. Philadelphia queensware with scalloped shell edge. L. 8". (Courtesy, Independence National Historical Park.)

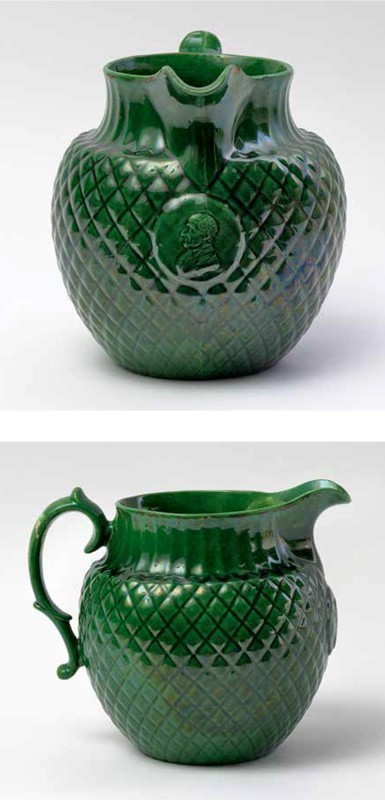

Pitcher or jug, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1810–1820. Philadelphia queensware. H. 6 1/2". (Courtesy, Independence National Historical Park.) This is the only known example of Philadelphia queensware with enamel decoration.

Sugar bowl, attributed to David Seixas Pottery, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1816–1822. Lead glaze enriched with copper on earthenware. H. 7 3/4". (Collection of the author; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Detail of the gilded handle on the sugar bowl illustrated in fig. 8 (Photo, Robert Hunter.)

Pitcher or jug, David Seixas Pottery, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1816–1822. Lead glaze enriched with copper on earthenware. H. 9". (Courtesy, Museum of the City of New York.) The jug contains a portrait medallion depicting Gershom Seixas.

Metal die, Moritz Fürst, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1812. D. 3". (Courtesy, American Jewish Historical Society.)

Ewer, attributed to David Seixas Pottery, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1816–1822. Earthenware. H. 8 5/8". (Courtesy, Independence National Historical Park; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Detail of the handle of the ewer illustrated in fig. 12. (Photo, Deborah Miller.)

Basin fragment, attributed to David Seixas Pottery, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1816–1822. Earthenware. H. 3". (Courtesy, Independence National Historical Park; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Teapot, attributed to David Seixas Pottery, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1816–1822. Earthenware. H. 7 1/4", W. 10 1/2". (Courtesy, Independence National Historical Park; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Detail of the central medallion depicting the Great Seal of the United States on the teapot illustrated in fig. 15. (Photo, Robert Hunter.)

Detail of the handle of the teapot illustrated in fig. 15. (Photo, Deborah Miller.)

Detail of the impressed maker’s mark on the base of the teapot illustrated in fig. 15. (Photo, Robert Hunter.)

Teapot, attributed to David Seixas Pottery, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1816–1822. Earthenware. H. 6 3/4". (Courtesy, The Reeves Collection, Washington and Lee University.)

Sugar bowl, teapot, and creamer, attributed to David Seixas Pottery, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1816–1822. Earthenware. H. of teapot 6 1/4". (Private collection; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Reverse of the tea set illustrated in fig. 20. (Photo, Robert Hunter.)

Detail of the impressed maker’s mark on the base of the teapot illustrated in fig. 20. (Photo, Robert Hunter.)

Detail of the handle of the creamer illustrated in fig. 20. (Photo, Robert Hunter.) Like the teapot illustrated in fig. 15, the handle of this creamer appears to be hand formed, not press molded.

Detail of the base of the creamer illustrated in fig. 20. (Photo, Robert Hunter.) The initials “JB” were incised into the base of the creamer prior to firing.

Slip cup, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1800–1830. Red earthenware. H. 3 1/8". Mark: “JB” incised on base. (Courtesy, Independence National Historical Park.)

Sucrier, or sugar bowl with cover, England, ca. 1800–1810. Feldspathic stoneware. H. 5 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Detail comparing the central medallion on the feldspathic stoneware sugar bowl illustrated in fig. 26 and the earthenware sugar bowl illustrated in fig. 20.

(Left) Teapot, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1809–1827. Salt‑glazed stoneware. L. 8 1/2". (Courtesy, Michael Frechette and Tom Salvatore; photo, Robert Hunter.)(Right) Teapot, attributed to Chetham & Wooley, Longton, Staffordshire, England, ca. 1793–1801. Feldspathic stoneware. L. 10". (Courtesy, Graham Hueber; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Detail of the molded handles of the teapots illustrated in fig. 28. (Photo, Robert Hunter.)

Teapot, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1810-1830. Red earthenware. H. 7 1/4"; L. 9". (Collection of the author; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Mold, Simon Singer Pottery, Haycock Township, Bucks County, Pennsylvania. Plaster of Paris. H. 7". (Courtesy, From the Collection of the Mercer Museum of the Bucks County Historical Society.) Singer is known to have used secondhand molds in his pottery, some of which, like the one illustrated here, predated his operation by more than fifty years.

On a cold spring day in 2008 my colleague and I set about mending the thousand-plus broken ceramics laid out on the table before us. “Sticking” broken pottery back together is standard work for archaeologists, a task not unlike assembling a three-dimensional puzzle, where plates, pitchers, creamers, and chamber pots rise from the worktable like a phoenix from the ashes. This particular group was no different, with standard bits of creamware, pearlware, and the like, until we reached a pile of peculiar green fragments. At first glance they were not particularly interesting, just a bit different because of the bold green glaze and odd white body. As the pieces slowly turned into two teapots, however, we realized we had something special (fig. 1).

The realm of material-culture studies in archaeology focuses primarily on imported ceramics, objects with strong manufacturing histories that provide equally strong dates. Objects that do not fit neatly into those parameters are often overlooked, not because they are unimportant but because they are not well understood. I never felt particularly guilty about this until I came to Philadelphia and was forced to rethink my approach to the study of ceramics. The shear breadth of locally produced ceramics was unlike anything I had faced before. I had not encountered urban privies before, twenty-foot-deep holes chock-a-block with tens of thousands of artifacts. The collection I manage from the National Constitution Center site at Independence National Historical Park alone numbers more than one million artifacts. It is an archaeological experience few of us are granted, and so began my journey into urban archaeology and the ceramic products of Philadelphia.

Pottery in Demand

Philadelphia’s ceramic industry is no stranger to scholarship. Published research undertaken by both Beth Bowers and Susan Myers on the potteries of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Philadelphia still stand as the primary texts on the subject. The authors extensively documented the producers and products of early Philadelphia that successfully challenged utilitarian imports in the local market. Myers’s work is particularly important to this study of local refined wares as it focuses on Federal-period products, most notably Philadelphia queensware, a local white-bodied earthenware imitation of English creamware (fig. 2). In the lean years of Jefferson’s Trade Embargo and the War of 1812, a small group of resourceful entrepreneurs established local potteries that produced refined, white-bodied ceramics mimicking the cream-colored wares of England, which had initially been banned under the Embargo Act of 1807.[1]

One of the most successful entrepreneurs of this period was John Mullowny, a ship captain turned brickmaker who in 1810 established the Washington Pottery, which manufactured “red, yellow, and black coffee-pots, tea pots, pitchers, etc. etc.”[2] Although not a potter himself, Mullowny promoted new and innovative techniques in the production of his wares, including “Turn’d and Pressed Ware, (the latter being the first manufactured in America).”[3] Those improvements might have been introduced by James Charlton, an Englishman who served as the master potter at the Washington factory.[4] Like his later business partner Thomas Haig, a trained potter from Scotland, Charlton likely trained as a journeyman potter in England, where he became skilled in the manufacture of queens-ware. We see that pattern again in the business association of Alexander Trotter, master potter of the Columbian Factory who trained in Scotland, and proprietors Binny & Ronaldson, who provided financial backing to the operation. In all three factories British-trained potters were making English-style pots that purportedly were of equal quality to those made in Staffordshire or Liverpool. In addition to their skills in manufacturing pottery, these men brought with them knowledge of contemporary production techniques. Mullowny certainly employed those methods at his factory and introduced a variety of forms with decorations previously unseen in the local American market. He also might have been the first to introduce a true white-clay body in Philadelphia, although that remains unconfirmed. No marked examples of Mullowny’s Washington Ware have been identified, but the diversity of forms in his advertisements suggest that his manufactory was quite prolific and produced large quantities of table and ornamental wares for both local and national consumption.[5]

In March 1815 Mullowny offered the Washington Pottery for sale in Poulson’s Daily Advertiser.[6] Included in the sale were not only the pottery works, but also its contents and the entire stock of ready-made wares. Although the records from the sale have not survived, by 1817 a new pottery was operating at the site, under the direction of David Seixas.

David Seixas of New York

David Seixas was in born in New York City in 1788 to Gershom Mendes Seixas and his second wife, Hannah Manuel (fig. 3). The elder Seixas was a widely respected leader in the early American Jewish community, held in high esteem for his civic leadership and political support of the American Revolution. Through his many religious, social, and political connections David became actively engaged in a transatlantic network of traders and goods from an early age, connections that later brought opportunities for his children as well.

Seixas was first documented in Philadelphia in 1807, as an agent for merchant Harmon Hendricks, the builder of America’s first copper-rolling mill. Seixas worked for Hendricks through at least 1812, selling sheet metal and other building supplies from a store on Front Street.[7] An 1814 advertisement in the Pittsburgh Weekly Gazette for “Seixas Philadelphia manufactured black lead CRUCIBLES” marked his move into ceramic production, albeit for industrial purposes that possibly were connected to his former business.[8] In 1817 Seixas opened his crockery store on Market Street, and by the following year was listed in the Philadelphia City Directory as a queensware manufacturer on High Street west of Schuylkill 7th (present-day 16th) Street.[9] Like Mullowny, Seixas was not a potter but rather an entrepreneur whose interest in manufacturing led to the further development of refined ceramics production in the city. Seixas also had a profound lifelong interest in charity. Drawn to a group of deaf children that he often saw on the streets near his pottery, he developed a method of sign language that eventually led to his founding the Pennsylvania School for the Deaf in 1820 (fig. 4). He maintained his pottery while serving as head teacher of the school until 1821, when he was dismissed, an event that most likely led to the closing of the pottery in 1822.[10] Seixas then disappeared from the historic record until 1829, when he reappeared in New York; he remained there for the next three decades, engaged in a variety of business ventures. He was a noted inventor during that period, and developed new methods for manufacturing sealing wax, as well as enameled visiting cards, printer’s ink, and burning anthracite coal over the next twenty years. He is also credited with early experiments in daguerreotype photography, which he exhibited in Baltimore in 1840.[11] In 1860 or 1861 he moved to South Bend, Indiana, and became a partner in a department store with his brother Thomas. He died in South Bend on March 19, 1864.[12]

Philadelphia’s Green-Glazed “Liverpool Crockery”

Josiah Wedgwood and Thomas Whieldon first introduced green glaze on a refined white body in 1759.[13] Popular through the 1770s, the glaze was used most often on molded or slip-cast forms shaped like fruits or vegetables on a cream-colored body. By the early nineteenth century, green glaze was rarely used in England, although it became widely popular again in the 1860s with the rise of Victorian majolica.[14] The use of green as an embellishment on locally made Philadelphia ceramics was common by the mid-eighteenth century but it was applied almost exclusively to slip-decorated red earthenwares, which often had green copper oxide splotched across the face of the vessel (fig. 5). Green was also occasionally used on Philadelphia queensware to create a mottled surface on the body or to coat a molded plate edge in emulation of green shell-edged pearlware (fig. 6).

On November 1, 1817, the Niles Weekly Register ran a lengthy story on David Seixas’s Philadelphia factory, noting that the “white ware pottery” was made of native materials, fired according to Wedgwood’s pyrometer, and decorated with “ornamental painting performed with variously coloured glazes” that made it indistinguishable from European wares.[15] Green was listed as one of the “coloured glazes” available to customers, which, after a second firing, would “pass into a state of perfect vitrifaction.”[16]

By early September 1818, David Seixas began advertising his wares to the greater public. In Lancaster, Washington, and Alexandria he advertised that “Excellent white crockery ware is now made in Seixas’s factory, Philadelphia. The materials are said to be obtained in inexhaustible quantities.”[17] That same month, advertisements in two New York newspapers, the Rochester Telegraph and Otsego Herald, noted “White Crockery ware, of quality equal to European, is extensively manufactured in the neighborhood of Philadelphia, by Mr. Seixas, wholly from American Materials.”[18] The emphasis on the American production of a sophisticated white-bodied ware marked a transition from the Philadelphia queensware made by potters operating just a few years earlier. This new product was meant to be indistinguishable from its imported counterparts and therefore a considerably stronger competitor in the marketplace.

Five archaeological vessels, including two of the marked examples, have been identified in Philadelphia collections (two teapots, a ewer, and two basins), and all five can be dated to the first quarter of the nineteenth century by their archaeological context.[19] An additional six intact vessels are known: a pitcher at the Museum of the City of New York; a teapot in the Reeves Collection at Washington and Lee University; and, in private collections, a recently discovered tea set consisting of a teapot, sugar bowl, and creamer; and a second sugar bowl. Only two surviving and two archaeological objects can be firmly connected to the factory by makers’ marks.

Manufacturing Techniques

Seixas’s green-glazed crockery can be identified by a number of attributes, among them the body composition, glaze, manufacturing characteristics, and overall product quality. All identified examples have a refined white body, although the quality of the paste varies considerably. Small inclusions, possibly iron, are visible in all of the archaeological examples.[20]

The Niles Register noted that a variety of colors were used at the factory, all prepared “of oxide of lead and powdered flint—and all colours are imparted to it by the addition of metalic [sic] oxides—of zinc for straw yellow, of cobalt for blue, of iron for red, of chromate for green (this is prepared from the Baltimore chromate of iron). . . .”[21] The green-glazed objects in this study, along with two possible examples in yellow, are the only examples of Seixas’s pottery that have been identified at this time. The color of the glaze ranges from a light to a deep emerald green that can pool to a very dark green or black. Glaze loss on the surface is common on the known vessels, particularly on joints or high, curved spaces like handles.

Wheel throwing and press molding were used to produce the variety of forms at the Seixas factory. Visible mold seams beneath the spout and handle on the gallon pitcher point to it being press molded. The ewer and two bowls were thrown on a wheel and finished on a lathe.

Surface treatments include slip banding, enameling, and/or gilding over the glaze. Black slip is prominent on several examples and was used primarily to define decorative borders and possibly to cover imperfections. There are also traces of gilding around the rim of the intact pitcher. The Niles Register noted that “ornamental painting is performed with variously colored glasses, ground to an impalpable power and mixed with essential oils—these are melted on the ware in an enamel kiln, by a heat at which the glaze softens.”[22] Vessels requiring painting and/or gilding were likely sent to George Bruorton, a china gilder who in 1818 opened a factory for “China Gilding and Painting” a block away from the Seixas factory. Bruorton advertised that he could “enamel and gild arms, crests, cyphers, borders or any device on china and queensware” and warranted his gilding equal to any on imported products.[23] A Philadelphia queensware pitcher excavated at Independence National Historical Park might be evidence of collaboration between Seixas and Bruorton (fig. 7). The pitcher is decorated with an enameled floral swag in an unusual burgundy color, and the overall bright “straw yellow” glaze on a white body suggests that it is very likely a product from the Seixas pottery.[24] A green-glazed sugar bowl with traces of gilding on one of the handles may also be evidence to the partnership between Seixas and Bruorton (figs. 8, 9).

Two of the green-glazed vessels also have engine-turned decoration; a third has rouletted decoration. It has long been assumed that engine turning was used only by potters in England during this period, but machinists were working in Philadelphia who specialized in ornamental lathe manufacture as early as 1808.[25] It is likely that John Mullowny of the Washington Pottery, who advertised “Turn’d and Pressed Ware” in 1812, was the first to use engine lathes for ceramic production in Philadelphia.

David Seixas employed a variety of production methods to manufacture a diverse range of products at his Philadelphia pottery. Using the equipment he purchased from Mullowny, he was able to build on an established legacy of successful ceramic production. The ready-to-use equipment and trained workers from the Washington Pottery, along with a large stock of ready-to-sell wares, would have made for an easy transition for Seixas and helped him explore and introduce new materials and techniques.

The Gershom Mendes Seixas Pitcher

The most outstanding example of the small assemblage of green-glazed wares attributed to the Seixas pottery is an emerald green pitcher housed in the collections of the Museum of the City of New York, that descended through the family of Seixas’s sister, Sarah Abigail Kursheedt (fig. 10).[26] The diamond-molded or “quilted” pitcher is nine inches high and eleven inches in diameter at the rim. The molded diamonds run vertically from the base to the shoulder, where they meet vertical flutes. The scrolled handle was cast as two separate pieces, likely from two molds for full-size handles intended for smaller vessel forms, and are not evenly aligned. The pitcher also exhibits uneven glazing and an area of loss on the handle. A small chip of clay protrudes from the neck, and there are small firing cracks throughout the surface of the handle, spout, and body.

The most compelling element of the pitcher is the portrait medallion featuring the profile of Gershom Mendes Seixas, David’s father. It almost certainly was cast from a metal die depicting the elder Seixas that was originally produced by renowned engraver Mortiz Fürst, which David had commissioned in honor of his father. The die, which is now in the collection of the American Jewish Historical Society, was first documented in the proceedings of the American Philosophical Society in 1812, when David donated to the society an “impression in paper of a die cut by Furst in this city, of his father Gershom M. Seixas” on “account of its superior execution” (fig. 11).[27] A later restrike of the die revealed the previously unnoticed signature of Fürst, a Jewish immigrant who came to Philadelphia from Slovakia in 1807 and went on to become a famed engraver at the U.S. Mint.[28]

The quality and sophistication of the jug far exceeds that of other known period vessels of Philadelphia manufacture, although it must be assumed that the mold itself came from the Washington Pottery.[29] The jug is critical to this study as it exhibits the characteristics that define David Seixas’s refined green-glazed earthenware, and provides a basis for comparison with archaeological and intact vessels.

Archaeological Evidence

The six archaeological examples believed to be products of Seixas’s pottery were excavated from sites at Independence National Historical Park in Old City, Philadelphia. A ewer and basin recovered from Block 1 of Independence Mall (where the Liberty Bell Center now stands) were the first to be identified as possible Seixas products. They came from a privy associated with the home of Alexander Turnbull, a Scottish cabinetmaker who lived and worked at the site from 1801 to 1826.[30] Additionally, two molded teapots were unearthed from the National Constitution Center site, two blocks to the north of the Trumbull lot, in a communal privy located behind a row of five tenements that were in use from about 1775 until they were torn down in the 1930s.[31] Analysis of the artifacts from the privy is ongoing, but a preliminary mean ceramic date (MCD) of the level that contained the teapots suggests that they were discarded sometime between about 1825 and 1833.[32]

The ewer recovered from the Turnbull privy is one of three examples bearing engine-turned decoration identified during this study (fig. 12).[33] The ewer has vertical S-curve panels under eight bands of horizontal lines across the surface of the body. A cross section of the body reveals the decoration was cut into the surface, a result of being mechanically turned on a lathe while using a curved knife to achieve the vertical S-curve design.[34] The 1817 Niles Register article noted that vessels at the Seixas factory were formed “on wheels of horizontal and vertical movements,” which indicates that an engine lathe was in use there.[35] That engine lathe has not been accounted for in the documentary record, but numerous other examples of engine-turned decoration on both white and red earthenware vessels show that they were common to local manufacture, possibly beginning with Mullowny as early as 1812.[36] The only other documented lathes operating in the city at that time were in the pottery shop of Abraham Miller and Son at 7th and Filbert Streets; three turning lathes were listed in an 1821 inventory of the shop’s trade stock, but there is no indication they were mechanically operated.[37] The lathes in use at the Miller factory were probably simple turning lathes used to create a controlled movement for ease in finishing and decorating products on the horizontal axis of the body. The one at the Seixas pottery, however, was an engine-driven, rose-and-crown lathe that could move vertically in addition to the horizontal movements found on traditional lathes.[38] No other documented use of a rose-and-crown lathe operating in an American pottery during this period is known. The expense of operating such a complex machine might ultimately have proved to be cost prohibitive, but Seixas’s attempts at regular production using sophisticated equipment ushered in a new period of refined ceramic manufacture that would persist throughout the century.

Four applied black-slip lines at the collar and a ribbed handle complete the decoration of the ewer. Like the other examples of Seixas’s work, the ewer has several manufacturing flaws. The terminal of the handle is offset and there are multiple tool marks across the body (fig. 13). The glaze is irregular along the curve of the spout and a chip of clay has adhered to the body. It is possible that originally the ewer was gilded, although no traces of the decoration survive.

A green-glazed basin that was likely coupled with the ewer was also recovered from the Turnbull privy. The body has a band of vertical flutes just beneath the rim that were rouletted rather than engine turned (fig. 14). A second basin was excavated three blocks from Independence Mall, on Race Street between 3rd and 2nd Streets.[39] It is engine turned across the body, like the ewer, but lacks the S-curve design. Both basins have a rounded foot, not the standard wedge foot seen on English basins of the period. The second vessel also has a piece of clay stuck to the interior of the bowl with an area of glaze loss around it.

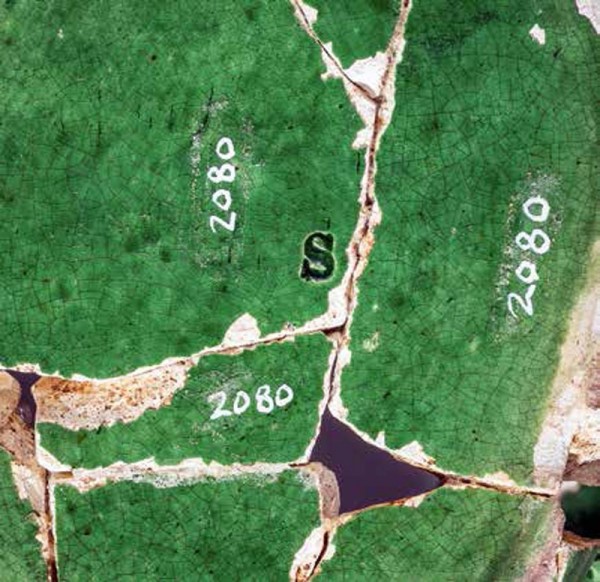

The two teapots from the National Constitution Center have thin, chalky white bodies under a green glaze (fig. 15). The relief molded decoration is a combination of crisply molded flowers and scrollwork against a stippled background. Two central medallions placed on opposite sides of the body—the Great Seal and Columbia—are equally well executed (fig. 16), but the spouts and handles are poorly formed and haphazardly applied (fig. 17). One intact lid, while nicely molded, is pinched just below the finial where it was pulled from the mold. No attempt was made to repair the pinch marks, giving the lid a drawn, narrow appearance. The handle of one teapot is tightly pinched with a noticeable indentation at the center, and the spout of the same vessel has visible finger marks at the terminal where it was roughly applied. Most importantly, both teapots are marked with an impressed “S” on their base (fig. 18). A nearly identical but slightly larger intact teapot is housed in the Reeves Collection at Washington and Lee University (fig. 19). The decoration on its body and the form of the spout, handle, and lid are the same as those to the excavated examples, and it shares similar manufacturing flaws, including a pinched lid. This teapot is marked on the base with an impressed “X” with hash marks across each point.

Recently, a previously undocumented green-glazed tea set consisting of a teapot, creamer, and sugar bowl was discovered at a Pennsylvania auction house (fig. 20).[40] All three vessels in the set have the same Great Seal and Columbia motif found on the teapots excavated in Philadelphia and the surviving example from the Reeves Collection (fig. 21). The teapot from the set is also marked “S” on the base (fig. 22) and, like the excavated examples, all three vessels lack the refinement of similar English types. The teapot and creamer have clumsily applied handles, particularly the creamer, which looks like it might have been molded by hand rather than pressed in a mold (fig. 23).

The creamer is signed with the entwined initials “JB” on the base (fig. 24). In what at this time can be described only as a curious coincidence, a slip cup inscribed with the same initials was excavated from the same deposit as the two Seixas teapots at the National Constitution Center site (fig. 25). While the owner of the slip cup remains unknown, such a vessel would have been owned only by the potter who used it for decorating his wares. Is it possible that the slip cup was used at the Seixas pottery and that the unknown “JB” had a hand in making the creamer? While it is unlikely that we’ll ever find the answer to what has become a burning question, the similarities between the script on the slip cup and creamer are intriguing.

The teapots share an important connection to dry-bodied English stoneware, particularly Castleford-style white feldspathic stoneware of the same period. The floral decoration on the body and lid have elements that are identical to contemporary feldspathic stoneware patterns, as are the medallions with images of the Great Seal and Columbia (fig. 26). A brown salt-glazed stoneware teapot that was found in the Northern Liberties section of Philadelphia is similarly modeled after an English vessel (fig. 27).[41] Made of the same materials as utilitarian salt-glazed stoneware, the teapot is identical to feldspathic stoneware teapots made by Chetham & Woolley of Longton between ca. 1794 and 1807 (fig. 28).[42] While the outward appearances contrast greatly due to their being made of different materials, the design elements are the same down to the asymmetric imperfections of the medallions on either side of the main panels. The handles and spouts are also consistently molded (fig. 29). It is likely the excavated teapot was made in Philadelphia by Branch Green, a stoneware potter who was working on 2nd Street above the Germantown Road, six blocks from the site where the teapot was recovered.[43]

The similarities between the English and American teapots strongly suggest that the Philadelphia potters, and in this case David Seixas, were casting molds directly from English pots to produce their earthenware products. Casting molds from existing vessels was not unheard of in the ceramic industry. For example, The Panorama of Professions and Trades; or Every Man’s Book, published in Philadelphia in 1837, notes the use of plaster molds for pressing:

Vessels, or parts of vessels, which are of an irregular shape, and which cannot be formed on the wheel, are usually made by a process called pressing. This kind of work is executed in moulds made of plaster of Paris, and these are formed on models of clay or wood, which have been made in the exact shape of the proposed vessel. Sometimes individual specimens of the wares of one country or pottery are used as models in another; in such cases, the expense of the moulds is considerably diminished.[44]

It is also possible that the pottery contracted with a local modeler or mold maker to produce detailed plaster molds. As noted earlier, John Mullowny advertised pressed wares at his Washington Pottery in 1812. This would have certainly required a mold, although Mullowny didn’t describe how his molds were manufactured. Several additional potters in the city were documented as having “moulds” in their shops in the 1820s.[45] Two of them, Abraham Miller and Thomas Haig, were producing fine wares at their respective potteries, most notably black, red, and brown-red earthenware teapots and other hollow table forms. Haig and Miller entered numerous tablewares into the Exhibitions for American Manufacturing at the Franklin Institute beginning in 1824, where both were commended for making ceramics that were “equal, if not superior to the imported.”[46] The black and brown ceramics made by Haig and Miller, while difficult to attribute to a specific pottery because of their similarities in body, form, and glaze, are commonly found at archaeological sites in Philadelphia. Most are wheel thrown with globular or double ogee bodies and rouletted decoration, but others are molded in the popular neoclassical style with vertical rounded flutes and braided collar (fig. 30). A plaster mold of this form survives in the collection of the Mercer Museum in Doylestown, Pennsylvania, and is attributed to the later nineteenth-century potter Simon Singer from Haycock Township, Bucks County (fig. 31). The form would have been quite dated by the time Singer owned it, which suggests that he obtained it from another pottery, possibly one in Philadelphia.[47] It remains unclear if the mold was manufactured by a mold maker or if an English vessel had been used as a model. It is a common form of the period that can be found in mediums other than ceramic, particularly silver.

The cost-cutting measures of using English ceramics for casting molds would certainly have been attractive to entrepreneurs like David Seixas, whose manufacturing costs and small production scale made his refined products more expensive than imports, which by 1816 were once again flooding the American market. Employing local craftsmen to produce molds, while potentially more expensive, likely had little impact on the overall cost of the vessels they produced. As noted by the judges of the Franklin Institute, Abraham Miller’s red earthenware articles were “cheap,” to the point that they had “excluded the foreign wares from the American Market.”[48]

Conclusion

The eleven known vessels described here make for limited but compelling proof that David Seixas was making green-glazed, white-bodied refined earthenware in Philadelphia from 1816 to 1822. The undeniable origins of the diamond-molded pitcher with the portrait of Gershom Seixas, coupled with the Niles Weekly Register announcement and archaeological evidence, strongly suggest the Market Street manufactory was producing credible imitations of English crockery. As the first manufacturer in the city to produce a pure white body coated in a variety of colorful glazes, Seixas played a brief yet pivotal role in the history of ceramics production in Philadelphia. Like John Mullowny before him, Seixas reshaped the local ceramics market by introducing new and improved products meant to compete with imported wares. Were these highly successful ventures that transformed the marketplace? No. But by employing cutting-edge techniques and skilled potters to produce improved locally made wares, Seixas set the stage for the next generation of ceramics manufacturers, such as William Ellis Tucker, who would go on to establish the city’s first successful porcelain factory in 1826.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Many thanks to Jed Levin and Karie Die-thorn at Independence National Historical Park and Janet Johnson at the State Museum of Pennsylvania for their generous access to archaeological collections in their care. Rob Hunter greatly enhanced this article by finding the surviving examples I could not. I am also grateful to Michael Frechette, Graham Hueber, Chris Rowell, and Tom Salvatore for sharing objects from their personal collections, and for my many friends and colleagues who have corresponded with me over the years, specifically Ron Fuchs, Pat Halfpenny, Willie Hoffman, Meta Janowitz, and Tom Kutys. I would never have started this decade-long search without Dennis Pickeral. He is always there for me, providing insight, advice, and encouragement.

Susan H. Myers, Handcraft to Industry: Philadelphia Ceramics in the First Half of the Nineteenth Century (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1980), p. 5.

Philadelphia Aurora General Advertiser, June 22, 1810, and November 17, 1810.

Philadelphia Aurora General Advertiser, January 28, 1812. This ad was run locally and out of state into early 1813.

J.C.A. Stagg, ed., The Papers of James Madison: Digital Edition (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2010), http://rotunda.upress.virginia.edu/founders/JSMN-03-03-02-0102 (accessed July 22, 2015). The letter was written to President Madison on October 26, 1810. Madison’s response, if any, has not been identified.

Myers, Handcraft to Industry, pp. 78–79. The March 1815 advertisement offering the pottery for sale notes that the ware was particularly successful in New Orleans and other Southern markets prior to the War of 1812.

The closing and subsequent sale of the pottery in 1815 was prompted by Mullowny’s appointment as American Consul General at Tenerife in the Canary Islands by President James Monroe. In 1820 he was further appointed Consul General of Morocco in Tangiers.

Philadelphia Gazette, March 5, 1812. Similar ads often ran in the paper beginning in 1811.

Isaac Harris, “Seasonable Goods,” Pittsburgh Weekly Gazette, November 29, 1814.

The Philadelphia City Directories typically have a two-year lag time. This makes it likely that David Seixas was active at the pottery by 1816, just a year after Mullowny offered the pottery for sale.

Seixas was dismissed as headmaster after being accused of misconduct involving a female pupil at the school. It is believed by many that the accusations stemmed from anti-Semitic feelings by members of the school’s board of directors. Despite being found guilty by them in 1822, a year later Seixas was honored by the State of Pennsylvania for his work with the deaf. For more information, see Documents in Relation to the Dismissal of David G. Seixas, from the Pennsylvania Institution for the Deaf and Dumb, Published for the Information of the Contributors, in Pursuance of a Resolution of the Board of Directors, Passed the 3d of April, 1822 (Philadelphia: Printed by Order of the Board of Directors, 1822), available online at https://archive.org

/details/gu_documentsrela00penn (accessed May 20, 2019).

Daily National Intelligencer (Washington, D.C.), March 17, 1840.

H. Van Allen, “David G. Seixas,” in American Annals of The Deaf, ed. Edward Allen Fay (Washington, D.C.: The Conferred of Superintendents and Principals of American Schools for the Deaf, 1913), pp. 180–87.

Robin Hildyard, English Pottery, 1620–1840 (London: V&A Publications, 2005), pp. 90–92.

A relief-molded pitcher in the Victoria & Albert depicting Liberty and a bust of Sir Francis Burdett, a popular early-nineteenth-century reformist English politician, is glazed with a deep green with traces of gilding across the body. See http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O150671/jug-unknown/ (accessed May 20, 2019). The pitcher is attributed to Yorkshire, England, 1800–1830. A feldspathic stoneware jug, also in the collection of the Victoria & Albert, with relief-molded decoration of two cherubs and “Burdett forever” enameled across the shoulder, was made in Staffordshire, England, ca. 1800–1810; see http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O150867/jug-unknown/ (accessed May 20, 2019). Burdett was at his professional peak in the first two decades of the nineteenth century.

As quoted in Myers, Handcraft to Industry, p. 93. The story first ran in the Philadelphia Freeman’s Journal in September 1817; subsequent runs were in the Niles Register (Baltimore, Md.), Albany Gazette (Albany, N.Y.) The Watch-Tower (Cooperstown, N.Y.), The Hampshire Gazette (Northampton, Mass.), and the National Advocate for the Country and The Columbian, both of New York City, through 1818.

National Advocate for the Country, December 2, 1817.

Alexandria Herald, September 18, 1818. The advertisement also ran in the City of Washington Gazette, September 14, 1818, and the Lancaster Journal, September 21, 1818.

Rochester Telegraph, September 15, 1818.

This study is specific to archaeological collections from Philadelphia sites. The sites assessed for potential examples of Seixas material were limited, and future efforts should reexamine older artifact collections from Philadelphia as well as sites outside of the region, specifically New York, Baltimore, the Carolinas, and New Orleans.

National Advocate for the Country, December 2, 1817. “The principal of the materials are clay and flint. The former is of a grayish blue colour, and contains pyrites of Sulphur and iron chemically combined, the presence of which impairs the colour of the ware.”

Ibid.

Ibid.

The Philadelphia Gazette, November 7, 1817.

John Mullowny also advertised for decorated wares in the Philadelphia Aurora General Advertiser in 1810–11: “Any device, cypher, or pattern, put on China or other ware, at the shortest notice, by leaving orders at the ware-house.” Mullowny’s employment of and/or business relationship with a china painter has not been documented at this time.

Deborah L. Miller, Meta F. Janowitz, and Allan S. Gilbert, “Identifying Red, Brown, and Black Philadelphia ‘China’ through Compositional Analysis: Initial Results,” American Ceramics Circle Journal 19 (2017): 106–7.

The pitcher is in the Brooklyn Collection of the City Museum of New York (32.91.2). It was donated to the museum in 1933 by Mrs. Louis J. Reckford. Louis J. Reckford was the son of Miriam Louis King, who was the great-granddaughter of Sarah Abigail Seixas Kursheedt. Sarah Abigail was Gershom Seixas’s oldest surviving child and David’s eldest sibling.

Early Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society for the Promotion of Useful Knowledge, Compiled by One of the Secretaries from the Manuscript Minutes of Its Meetings from 1744–1838 (Philadelphia: Press of McCalla and Stavely, 1884), p. 433. Moritz Fürst went on to become one of the most recognized engravers in early America. Working for the United States Mint, he struck official portraits of several sitting presidents, among them James Monroe and Andrew Jackson.

A medal was cast from the die sometime after 1816 that has an added inscription -“GERSHOM M. SEIXAS CONGREGATIONIS HEBRAEAE SACERDOS NOVI EBORACI” is now in the collection of Columbia University in New York.

John Mullowny first advertised “Handsome GALLON PITCHERS, 31 cents wholesale” in the Philadelphia Aurora General Advertiser in January 1812.

Rebecca, ed., “After the Revolution—Two Shops on South Sixth Street: Archeological Data Recovery on Block 1 of Independence Mall,” report prepared for the National Park Service, Denver, by John Milner Associates, Inc. (Philadelphia, 2004), p. 9.

Philadelphia Contribution Insurance Survey S01827 for 1774, 1827, and 1848 for Caleb Cresson and John Thomason. www.philadelphiabuildings.org/contributionship/ho_display.cfm?RecordId=CONTRIB-S01827 (accessed May 2, 2017).

The privy contained 40,578 ceramic artifacts alone. Given the communal nature of the deposits, and a high rate of mobility among the tenants, we have not been able to link specific artifacts to individuals or families living in the tenements.

Juliette Gerhardt of John Milner Associates first reported on the ewer and basin in Rebecca Yamin, “After the Revolution,” pp. 30–31.

Don Carpentier, personal communication, June 21, 2014.

Myers, Handcraft to Industry, p. 83.

For additional information on white and red earthenware vessels with engine-turned decoration excavated in Philadelphia, see Miller et al., “Identifying Red, Brown, and Black Philadelphia ‘China.’”

Myers, Handcraft to Industry, p. 98. The Millers were the first dynastic family of potters in Philadelphia. Patriarch Andrew Miller first appears as an indentured potter in a 1765 inventory for the household goods of potter John Gassar of the Northern Liberties. Shortly thereafter he was operating his own pottery on Elfreth’s Alley in Old City, Philadelphia. His sons and grandsons continued the family business until the late nineteenth century, although they transitioned to stoneware and firebrick production mid-century.

Miller et al., “Identifying Red, Brown, and Black Philadelphia ‘China,’” pp. 107–8; Jonathan Rickard and Donald Carpentier, “The Little Engine That Could: Adaptation of the Engine-Turning Lathe in the Pottery Industry,” in Ceramics in America, ed. Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2004): 78–99; Jonathan Rickard, Mocha and Related Dipped Wares, 1770–1939 (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England in association with Historic Eastfield Foundation, 2006), p. 36.

The basin was excavated from a privy at 232 Race Street by avocational digger Chris Rowell; the privy also contained several sherds of bisque-fired local queensware. The artifacts are from a trash deposit dating to ca. 1780–1820.

The set sold at Pook and Pook in Downingtown, Pennsylvania, on September 11, 2018, lot 526. It was advertised as a Staffordshire three-piece service.

The teapot was excavated from a privy at 847 N. 3rd Street in the Northern Liberties neighborhood of Philadelphia by avocational diggers Michael Frechette and Tom Salvatore. The artifacts recovered with the teapot were likely deposited in the 1830s or early 1840s.

Diana Edwards and Rodney Hampson, English Dry-Bodied Stoneware: Wedgwood and Contemporary Manufacturers, 1774–1830 (Suffolk, Eng.: Antique Collectors’ Club, 1998), pp. 123–24. The attribution of Chetham and Woolley for the English feldspathic stoneware teapot is based on sherds recovered from the pottery site as well as surviving marked examples. See ibid., p. 155, for a feldspathic example.

Although Green is known for his utilitarian stoneware with decorative coggling, he is the only documented potter in Philadelphia who was working with stoneware in the area at the time. He remained at this location until 1827, when he sold the factory to Henry Remmey Jr., a stoneware potter from Baltimore, Maryland.

Edward Hazen, The Panorama of Professions and Trades; or Every Man’s Book (Philadelphia: Uriah Hunt, 1837), p. 238.

When the partnership of potters Abraham and Andrew Miller Jr. was dissolved following Andrew’s death in 1821, an inventory of the pottery’s stock-in-trade was taken to settle accounts and divide assets. Included in the inventory were “Plaster, and other moulds,” among other shop-related tools and equipment. The inventories of potters Michael Gilbert and Thomas Haig Sr. taken in 1831 and 1832 also included molds. While they were producing some refined tablewares, the bulk of their business was in utilitarian wares, such as plates, chargers, pans, crocks, jars, etc. The molds mentioned here could also represent drape molds used in the production of the utilitarian objects.

As quoted in Myers, Handcraft to Industry, p. 99. See also Miller et al., “Identifying Red, Brown, and Black Philadelphia ‘China,’” pp. 98–123.

A plate in the collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art that was given to the museum by famed ceramics historian Edwin Atlee Barber is noted to have been made on a mold dating to 1810. The slip inscription reads: “This dish is made over the pattern of 1810 in Haycock, 1886 for H. H. Younk to E.A. Barber S. Singer.”

As quoted in Myers, Handcraft to Industry, p. 99.