The author examining green‑glazed ceramics at the Independence National Historical Park Archaeology Laboratory in 2018. (Photo, Robert Hunter.)

Coffeepot, attributed to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1807–1820. Philadelphia queensware with engine-turned decoration. H. 9". (Private collection; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Miniature portrait, David G. Seixas, attributed to John Carlin. Watercolor on ivory. (Courtesy, Pennsylvania School for the Deaf.)

Plate, Enoch Wood & Sons, Burslem, Staffordshire, England, ca. 1818–1848. Whiteware. D. 8 1/2". (Collection of the author; photo, Robert Hunter.) Transfer-printed image depicting the Philadelphia Asylum for the Deaf and Dumb, now the Pennsylvania School for the Deaf, ca. 1824.

Dish, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1770s. Slipware with green copper-oxide highlights. D. 11 3/4". (Courtesy, National Park Service, Independence National Historical Park, Inde-57214.)

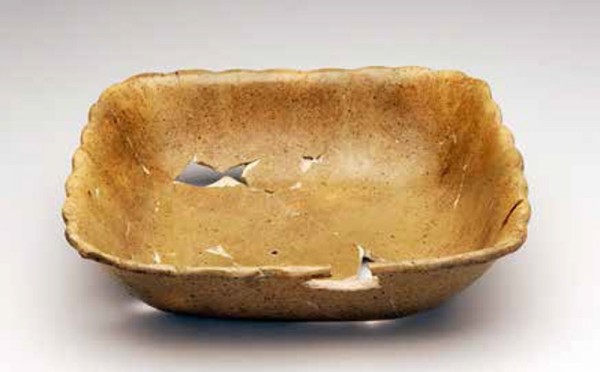

Dish, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1810–1820. Philadelphia queensware with scalloped shell edge. L. 8". (Courtesy, Independence National Historical Park.)

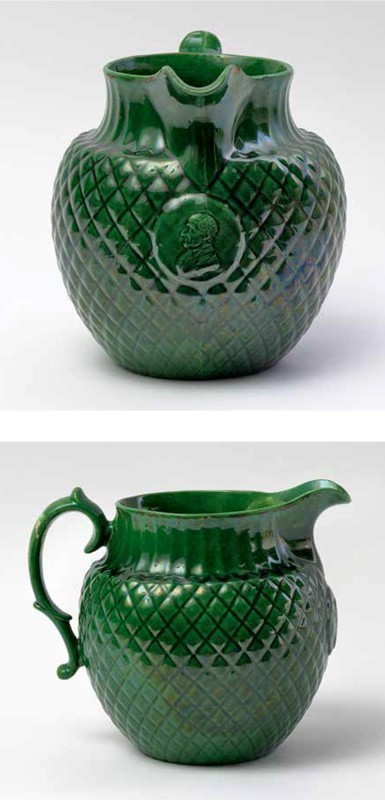

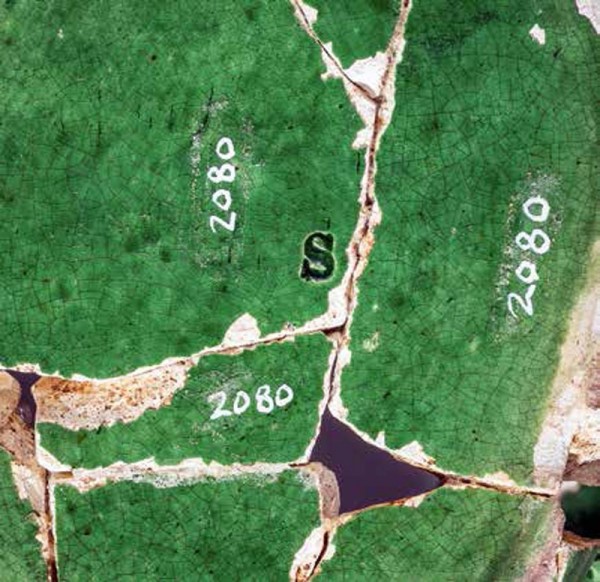

Pitcher or jug, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1810–1820. Philadelphia queensware. H. 6 1/2". (Courtesy, Independence National Historical Park.) This is the only known example of Philadelphia queensware with enamel decoration.

Sugar bowl, attributed to David Seixas Pottery, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1816–1822. Lead glaze enriched with copper on earthenware. H. 7 3/4". (Collection of the author; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Detail of the gilded handle on the sugar bowl illustrated in fig. 8 (Photo, Robert Hunter.)

Pitcher or jug, David Seixas Pottery, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1816–1822. Lead glaze enriched with copper on earthenware. H. 9". (Courtesy, Museum of the City of New York.) The jug contains a portrait medallion depicting Gershom Seixas.

Metal die, Moritz Fürst, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1812. D. 3". (Courtesy, American Jewish Historical Society.)

Ewer, attributed to David Seixas Pottery, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1816–1822. Earthenware. H. 8 5/8". (Courtesy, Independence National Historical Park; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Detail of the handle of the ewer illustrated in fig. 12. (Photo, Deborah Miller.)

Basin fragment, attributed to David Seixas Pottery, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1816–1822. Earthenware. H. 3". (Courtesy, Independence National Historical Park; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Teapot, attributed to David Seixas Pottery, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1816–1822. Earthenware. H. 7 1/4", W. 10 1/2". (Courtesy, Independence National Historical Park; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Detail of the central medallion depicting the Great Seal of the United States on the teapot illustrated in fig. 15. (Photo, Robert Hunter.)

Detail of the handle of the teapot illustrated in fig. 15. (Photo, Deborah Miller.)

Detail of the impressed maker’s mark on the base of the teapot illustrated in fig. 15. (Photo, Robert Hunter.)

Teapot, attributed to David Seixas Pottery, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1816–1822. Earthenware. H. 6 3/4". (Courtesy, The Reeves Collection, Washington and Lee University.)

Sugar bowl, teapot, and creamer, attributed to David Seixas Pottery, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1816–1822. Earthenware. H. of teapot 6 1/4". (Private collection; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Reverse of the tea set illustrated in fig. 20. (Photo, Robert Hunter.)

Detail of the impressed maker’s mark on the base of the teapot illustrated in fig. 20. (Photo, Robert Hunter.)

Detail of the handle of the creamer illustrated in fig. 20. (Photo, Robert Hunter.) Like the teapot illustrated in fig. 15, the handle of this creamer appears to be hand formed, not press molded.

Detail of the base of the creamer illustrated in fig. 20. (Photo, Robert Hunter.) The initials “JB” were incised into the base of the creamer prior to firing.

Slip cup, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1800–1830. Red earthenware. H. 3 1/8". Mark: “JB” incised on base. (Courtesy, Independence National Historical Park.)

Sucrier, or sugar bowl with cover, England, ca. 1800–1810. Feldspathic stoneware. H. 5 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Detail comparing the central medallion on the feldspathic stoneware sugar bowl illustrated in fig. 26 and the earthenware sugar bowl illustrated in fig. 20.

(Left) Teapot, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1809–1827. Salt‑glazed stoneware. L. 8 1/2". (Courtesy, Michael Frechette and Tom Salvatore; photo, Robert Hunter.)(Right) Teapot, attributed to Chetham & Wooley, Longton, Staffordshire, England, ca. 1793–1801. Feldspathic stoneware. L. 10". (Courtesy, Graham Hueber; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Detail of the molded handles of the teapots illustrated in fig. 28. (Photo, Robert Hunter.)

Teapot, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1810-1830. Red earthenware. H. 7 1/4"; L. 9". (Collection of the author; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Mold, Simon Singer Pottery, Haycock Township, Bucks County, Pennsylvania. Plaster of Paris. H. 7". (Courtesy, From the Collection of the Mercer Museum of the Bucks County Historical Society.) Singer is known to have used secondhand molds in his pottery, some of which, like the one illustrated here, predated his operation by more than fifty years.