Teabowl fragment, John Bartlam, Cain Hoy, South Carolina, 1765–1770. Soft-paste porcelain. H. of fragment 1 7/16". (The Charleston Museum; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The lead glaze on this archaeologically retrieved teabowl fragment has degraded, and portions were physically scraped away to reveal the underglaze decoration.

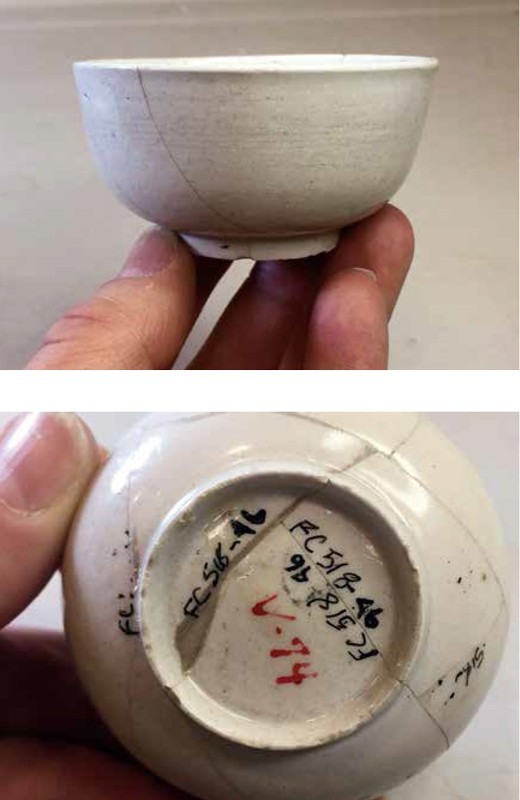

Saucer, American China Manufactory, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1770–1772. Soft-paste porcelain. D. 5 1/8". (Courtesy, Independence National Historical Park; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This example of a Bonnin and Morris saucer has hand-painted chinoiserie decoration (left). No antique examples of any of the teawares are known to survive, although they are mentioned in the documents of the factory. Note the distinctive “P” for “Philadelphia” mark (right), which has been found on virtually every known example of Bonnin and Morris. Like the Bartlam ware illustrated in figure 1, the lead glaze on these phosphatic bodies degrades chemically and reacts with soil when buried in the ground, creating the crusty, brown surface.

Punch bowl, attributed to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1772. Hard-paste porcelain. D. 5 1/2". (Courtesy, The Museum of the American Revolution; photo, Robert Hunter.) Recovered in 2014 from among nearly 85,000 artifacts found on the site of the new Museum of the American Revolution by archaeologists from Commonwealth Heritage Group, this bowl was initially thought to have a stoneware body. However, subsequent material analysis by Victor Owen and his colleagues revealed that it is true porcelain, and most likely had been manufactured in Philadelphia.

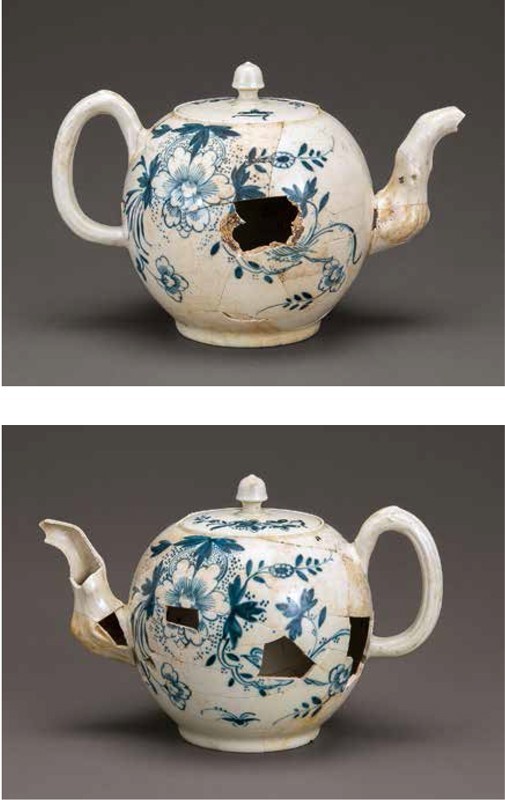

Teapot, attributed to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1767–1772. Hard-paste porcelain with a lead glaze. D. 5 1/2". (Courtesy, The Museum of the American Revolution; photo, Robert Hunter.) This newly analyzed decorated teapot has a hard-paste body related to the punch bowl illustrated in fig. 3. It was lead glazed, however, and decorated with brushed cobalt. Historical research suggests that this teapot may relate to an advertisement placed in 1767 in the Pennsylvania Gazette by Scottish immigrant merchant Alexander Bartram, which describes “Pennsylvania penciled teapots.” The date, of course, precedes the 1770 opening of the American China Manufactory owned by Gousse Bonnin and George Anthony Morris.

Teabowl, attributed to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1772. Hard-paste porcelain. D. 2 3/4". (Courtesy, Independence National Historical Park; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Punch bowl, attributed to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1772. Hard-paste porcelain. D. 5 1/2". (Courtesy, Independence National Historical Park; photo, Robert Hunter.) This undecorated small punch bowl is very similar to the example illustrated in fig. 1. It was recovered from a late-eighteenth-century privy deposit among a wide range of refined English earthenware and Chinese porcelain. Also found in association were two marked Bonnin and Morris porcelain sauceboats. INDE150343

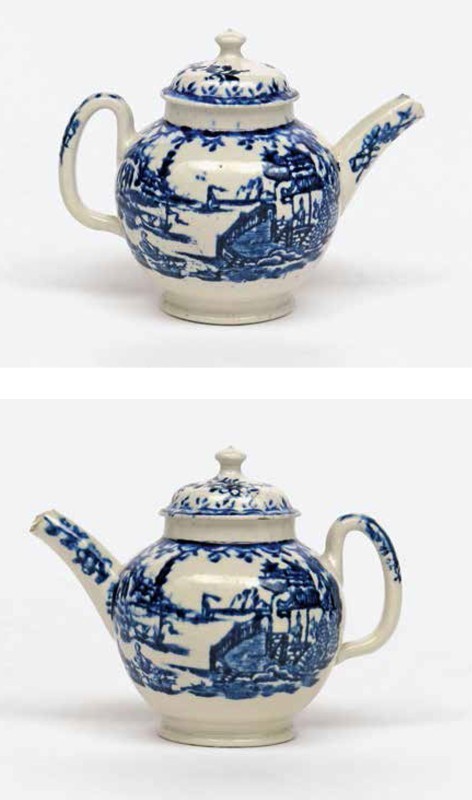

Miniature or toy teapot, Britain or America, ca. 1767–1770. Hard‑paste porcelain. H. 3 15/16". (Photo courtesy of Clare Durham, Woolley and Wallis Auctions.)

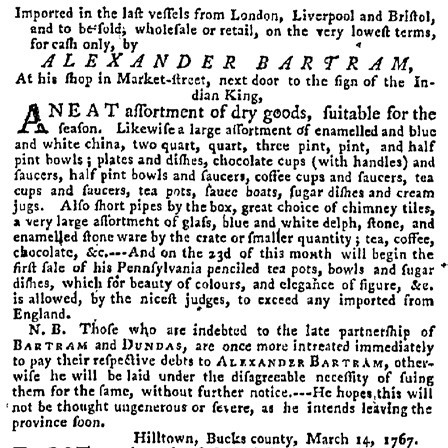

Advertisement placed by Alexander Bartram in the Pennsylvania Gazette, March 9, 1767.

Detail of the teabowl illustrated in fig. 5, showing the glaze inclusions.

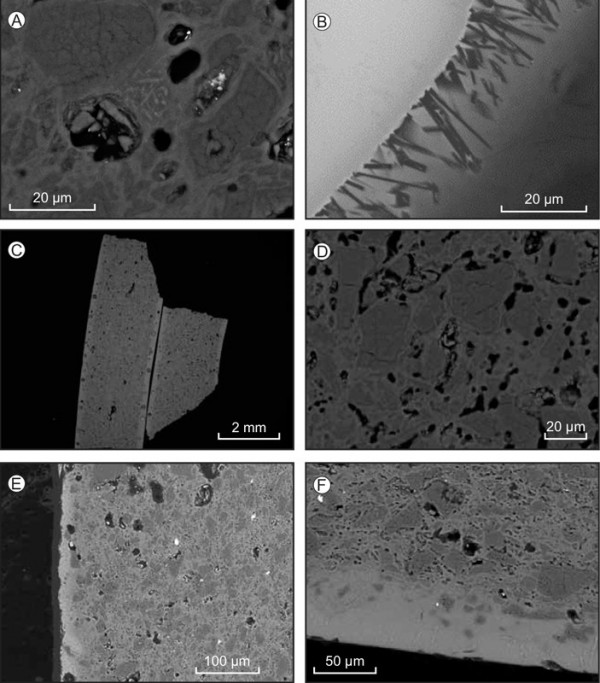

Backscattered-electron images: (A) the body of teapot V.213 showing mullite microlites (pale-gray needles in center of image); (B) its partly crystallized (K feldspar), integrated body‑glaze layer and the overlying lead-rich glaze; (C) overview of two fragments of the Franklin Court teabowl showing its salt glaze; (D) close-up of teabowl body showing an interstitial melt phase (pale gray) partly corroding silica polymorphs (probably α-quartz; medium gray); (E) the body and calcium-rich glaze (the narrow, pale gray, shown on the left of the image) of the Philadelphia bowl; and (F) a close-up of the body and partly crystallized (ternary feldspar [slender, white grains]) glaze on the bowl illustrated in fig. 6. Irregular medium-gray grains entrained by the glaze are silica polymorphs (probably α-quartz) from the ceramic substrate. The black patches in A, B, D, E, and F are pores.

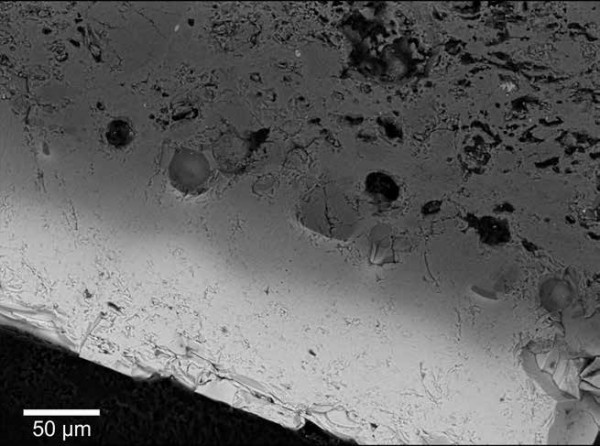

Backscattered-electron image showing the integrated body-glaze layer (medium-gray band) separating the lead-rich glaze (lower left) from the body (upper right) of the miniature teapot illustrated in fig. 7.

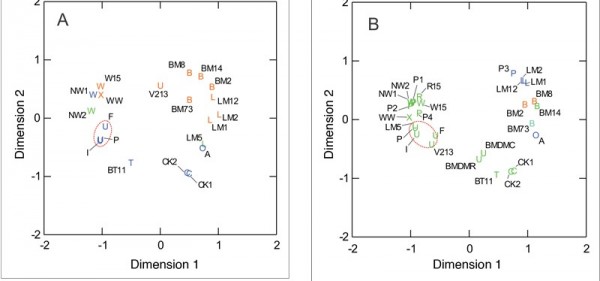

MDS diagrams for (A) glaze, and (B) paste compositions of teapot V.213, the Franklin Court teabowl (“F”), and the Philadelphia bowl (“P”) (all represented by the “U” symbols), together with aluminous-silicic porcelain sherds from the John Bartlam (“T”), and Worcester (“W”) sites, and intact Cookworthy (“Ck”) porcelain figures, and aluminous-silicic to S-A-C- porcelain sherds from the Limehouse (“LM”) and Bow (“A”-marked [first patent]; “O”) factory sites, and experimental, lead-bearing S-A-C porcelain from Pomona (“P”), Staffordshire. The lead-glazed true porcelain miniature teapot (see fig. 7) found in the UK is denoted by an “X.” Also plotted, for comparative purposes, are the compositions of phosphatic porcelain sherds from the Bonnin and Morris (“B”) site, and the composition of a zoned, mullite-bearing melt bleb (“BMDMR [rim] and BMDMC [core]”) in the Philadelphia punch bowl. Sample numbers are indicated. Note the clustering (red dashed fields) of key aluminous-silicic samples excavated in Philadelphia (see text). Colors distinguish the lead content of glazes—blue: low lead (<5,000 ppm Pb), green: medium lead (5,000–15,000 ppm Pb) and orange: high lead (>15,000 ppm Pb)—and paste compositions (green: aluminous‑silicic; orange: phosphatic; blue: S-A-C; turquoise: Pb-bearing S-A-C) in figures (A) and (B), respectively.

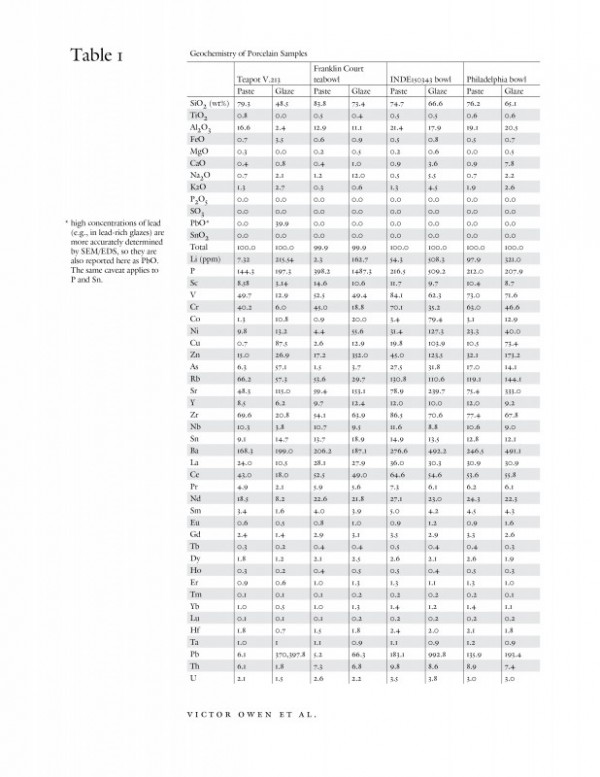

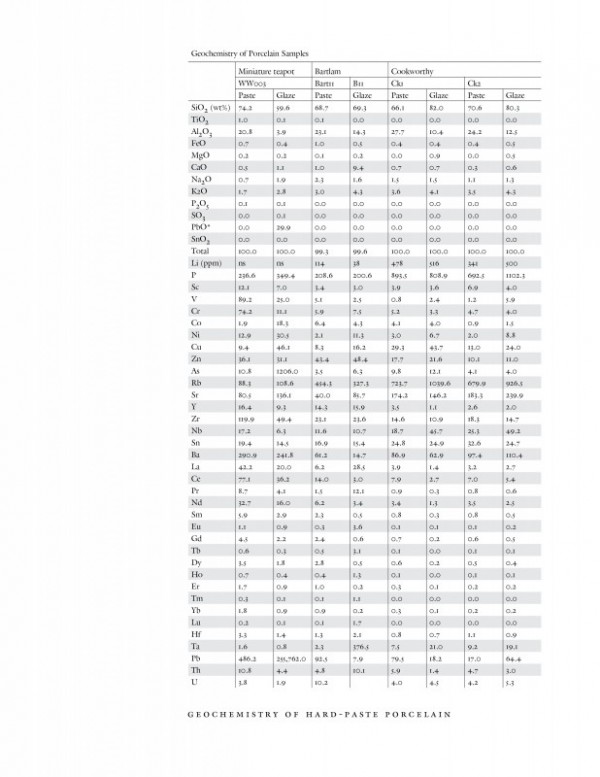

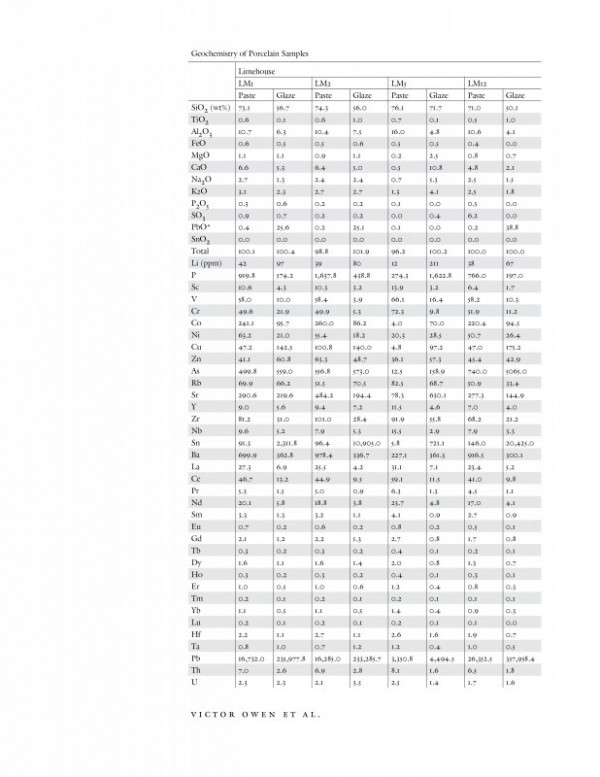

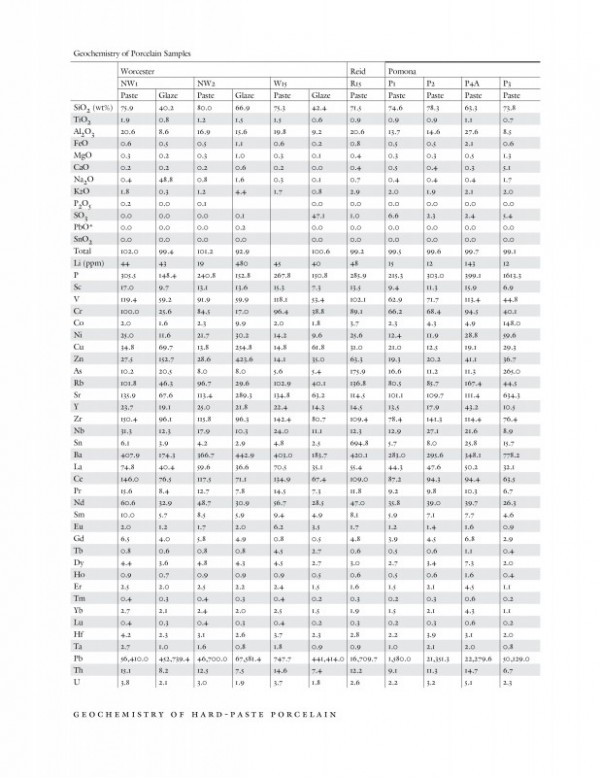

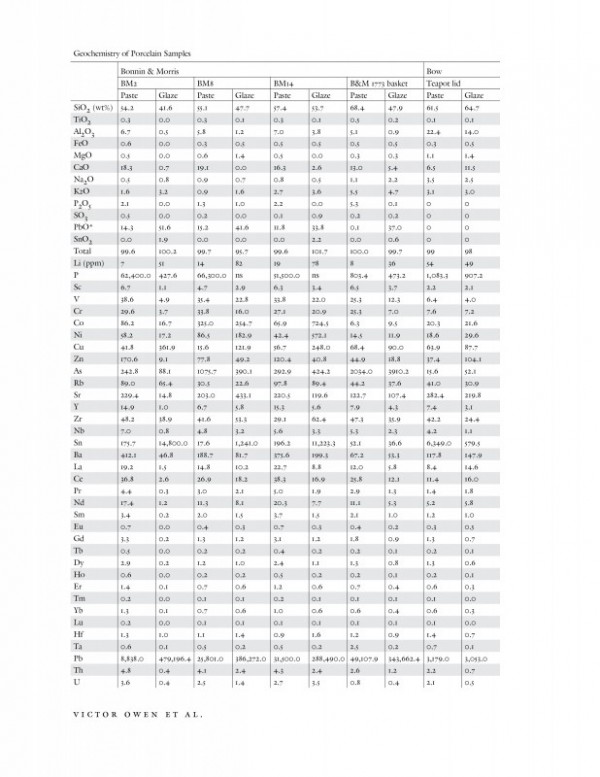

Table Geochemistry of Porcelain Samples

Table Geochemistry of Porcelain Samples

Table Geochemistry of Porcelain Samples

Table Geochemistry of Porcelain Samples

Table Geochemistry of Porcelain Samples

Introduction: The production of soft-paste porcelain in what is now the United States is thought to date back to the mid-1760s, when John Bartlam, a Staffordshire immigrant, apparently created phosphatic (bone ash) porcelain along with Staffordshire-style earthenware and stoneware at Cain Hoy, South Carolina (fig. 1).[1] A similar type of porcelain was subsequently manufactured shortly thereafter (ca. 1770–1773) by Gousse Bonnin and George Anthony Morris at the American China Manufactory in Philadelphia (fig. 2). Precisely when true Chinese-type porcelain with an aluminous-silicic paste and an essentially lead-free, high-temperature glaze was first made in America has been a subject of some debate. The discovery and analysis of an undecorated porcelain punch bowl from a privy on the site of the Museum of the American Revolution (MOAR) in Philadelphia has reinvigorated the discussion (fig. 3).[2]

The punch bowl has a partly crystallized labradorite, An61-69, unusually thin calcic glaze, and there are large melt blebs in its ceramic substrate.[3] The former feature suggests that the punch bowl was produced by someone unfamiliar with the production of very-high-temperature ceramic wares, while the latter feature indicates that the paste ingredients, including a low-solubility flux, probably china stone, were poorly mixed. These features suggest that the punch bowl was an experimental ware, which leads to the supposition that it was produced near where it was found.

This study describes three other well-vitrified wares with aluminous-silicic bodies also excavated in Philadelphia—a blue painted teapot (fig. 4), an undecorated teabowl (fig. 5), and another smaller, undecorated punch bowl (fig. 6)—and compares their mineralogy and geochemistry to the punch bowl (henceforth referred to as the “Philadelphia bowl”). The geochemical data are statistically compared to each other and diverse, broadly contemporary, mostly British wares, in order to place constraints on the place of manufacture of the analysed samples.

In addition to examples found in the Philadelphia context, we also describe here a miniature or toy-sized blue decorated porcelain teapot and cover that recently surfaced in the auction market in the United Kingdom (fig. 7). Even though it was found in the United Kingdom, this sample was included because, when analyzed, it proved to have a composition similar to the specimens found in Philadelphia.

Historical Background and Archaeological Context

It is not known when aluminous-silicic porcelain was first made in the America. An influential and widely traveled potter named Andrew Duché claimed to have made it in Savannah, Georgia, in the late 1730s, but that has yet to be confirmed by the existence of porcelain examples.[4] There is no doubt, however, that Duché had experience making high-temperature ceramics; he learned to produce stoneware at his family’s pottery in Philadelphia, and seems to have been the first person in America to produce stoneware south of Virginia. It is perhaps significant that Duché had returned to Philadelphia the year before the American China Manufactory began operations, and lived nearby in the Southwark section of the city.[5] It is certainly possible that the Philadelphia bowl originated at the American China Manufactory, and that Duché had a role in its creation.

Another contender for this title is Alexander Bartram, a Scottish immigrant and merchant who, on March 9, 1767, advertised in the Pennsylvania Gazette the sale of imported china and stoneware from England (fig. 8). The ad also announced “And on the 23d of this month will begin the first sale of his Pennsylvania penciled tea pots, bowls and sugar dishes, which for beauty of colours, and elegance of figure, &c. is allowed, by the nicest judges, to exceed any imported from England.” “Penciled” teawares were mentioned in two advertisements later that month, but then they disappear from the documentary record.[6]

The phrase “his Pennsylvania penciled tea pots” implies that those wares were in Bartram’s possession and may have been made at his pottery on Third Street in the Southwark section of Philadelphia.[7] The date of the advertisement, of course, precludes a Bonnin and Morris (ca. 1770–1773) origin. The adjective “penciled” historically refers to fine brushwork that appeared on many contemporary Chinese and British (e.g., Worcester) porcelains being imported to America. Many examples of “penciled” teawares have been found on archaeological sites of the period in Philadelphia, as well as many other sites along the Eastern seaboard.

Although Bartram does not mention specifically that his teawares were porcelain, the penciling to which he refers is consistent with the style of decoration on the blue painted teapot excavated from the Museum of the American Revolution. The teapot was recovered from the same brick-lined privy, Feature 16, as the Philadelphia punch bowl discussed above. Both were found among a vast amount of household and tavern-related ceramic and glass objects—tankards, bottles, pie dishes, chamber pots, porringers, diverse bowls.[8] Among the artifacts recovered from this privy were thirteen teapots, some of which, along with related teawares, are Chinese porcelain. The blue painted teapot, designated Vessel 213 (hereafter referred to as V.213), however, stood out as being distinct, and is a main subject of this essay (see fig. 4).

Another artifact on which we focus here is an undecorated white teabowl from Franklin Court in Old City, Philadelphia (see fig. 5). Franklin Court is a series of archaeological sites that includes five houses along the 300 block of Market Street—now known as the Market Street Houses—and an interior courtyard behind them where Benjamin Franklin’s house and print shop were once located. Archaeological investigations of Franklin Court began in the 1950s, but it was not until the 1970s that the Market Street Houses and the site of Franklin’s home were fully excavated.[9] Although Benjamin Franklin’s association with the site was the driving force behind the project, the archaeology itself yielded little evidence of Franklin’s life. The site of his house, along with its associated privies, wells, and print shop, were excavated, but few eighteenth-century artifacts were recovered and they could not be definitively tied to Franklin or his household. Excavations in the basements and backyards of the Market Street Houses, however, produced tens of thousands of artifacts dating from the early eighteenth through the mid-nineteenth century.

The privies located behind the Market Street Houses contained most of the artifacts recovered from the site. One of the privies, Feature 9, was located behind 314 Market Street, and it contained a large concentration of early- to mid-eighteenth-century artifacts, including the white teabowl described here. Also recovered were large numbers of white salt-glazed stoneware, as well as numerous examples of “transitional” earthenware products, which may have been local attempts to make copies of English tortoiseshell-type wares. Some of them were sufficiently high-fired that they resemble refined stoneware. Almost certainly, unidentified examples of Bonnin and Morris porcelain were in the feature, as well as parts of other ceramic objects; some stoneware pieces were likely made by the Duché family, although they have not yet been conclusively identified as such.[10]

The third artifact we describe here is an undecorated white punch bowl (sample INDE150343) recovered from the National Constitution Center site on the third block of Independence Mall (see fig. 6). The bowl is from Feature 26, a late-eighteenth-century privy deposit that originally was situated on the boundary line of two house lots on what was then Cherry Street. Preliminary research suggests the privy was used by the household of Benjamin Cathrall, a Quaker schoolmaster who lived at 55 Cherry Street ca. 1790–1801, although it is likely that multiple households, including tenants living at the rear of the lot, contributed to the privy fill.[11] The deposit contained a wide range of refined English earthenware and Chinese porcelain, as well as two marked examples of Bonnin and Morris porcelain. Both are bowls, either waste bowls or small punch bowls, with blue underglaze decoration, the first having a printed floral pattern, the second a painted Chinese landscape. There were also three additional undecorated white vessels from the feature—a porringer with a lid, a teapot lid, and a second punch bowl. A large dish painted with the same “penciled” pattern as that of the teapot from the Museum of the American Revolution was also recovered from Feature 26, although analysis determined that it is of English origin.[12]

Sample Description

The reconstructed teapot V.213 has a nearly spherical body with a crabstock-shaped spout, a rounded handle, and a lid with an acorn-shaped finial. The underglaze blue decoration, which depicts a stylized bird on a floral trellis, is identical to the “Liverbird” pattern made by Philip Christian & Son of Liverpool.[13] Rod Jellicoe, an expert on early English porcelain, has commented on the similarity of the form to teapots made in Liverpool; the spout shape was used by William Reid, the handle shape by Richard Chaffers and Philip Christian, and the decoration by Philip Christian.[14] Thin parts of the teapot are slightly translucent when strongly backlit. The outside (convex) surface of the teapot has a speckled pale-brown color; the inside (concave) surface is white. The analyzed sherd shows traces of this brown stippling on old broken edges, but the cut surface is white and glassy (vitrified).

The teabowl from Franklin Court has a white body and is undecorated. The exterior surface has a thick glaze that in some areas appears gray. It has several pits, and the glaze is damaged at the rim where it adhered to another vessel in the kiln. The bowl has two large black inclusions in the interior glaze (fig. 9), which has caused the glaze to craze across the interior surface. Like the teapot, it is translucent when backlit.

The small punch or waste bowl from the National Constitution Center site (see fig. 6) also a white body and undecorated, although there is heavy brown-to-gray/black staining on the interior and exterior. It is unclear whether the staining is a result of impurities in the glaze or from being overfired. It, too, is translucent, although a strong light is required.

The miniature or toy-sized porcelain teapot and cover identified as sample WW003 (see fig. 7) is printed in underglaze blue with the Cantilevered Garden pattern. The cover is printed with flower sprays, both with a painted berry or husk-type border in the Lowestoft manner. It has a simple loop handle with a double groove.

Analytical Methods

Pieces were removed from the teapot and analog samples and polished to a high finish using diamond pastes on glass and lapidary cloths. A scanning electron microscope (SEM) was used to analyze the samples and collect backscattered electron images (BEI). The equipment used was a LEO 1450VP SEM operated with a voltage of 20kV, an emission current of 272 uA, a beam current of 264 pA, and beam spot size of 5 nm. It was equipped with an Oxford Instrument INCA X-max 80 mm2, silicon-drift EDS detector. Count times were adjusted to the size of the area being analyzed: 40 s for spot analyses, 300–360 s for larger areas (averaging ~ 4 mm2 fields).

High-precision trace-element data were determined by laser-ablation ICP-MS at the University of New Brunswick. Data were reduced using Al (determined by SEM/EDS) as an internal standard.

Mineralogy and Geochemistry

Like the Philadelphia bowl, the body of the three Philadelphia-found artifacts described here consist of partly resorbed α-quartz (confirmed by Raman spectroscopy) and probable tridymite, mullite, and a melt phase (fig. 10A). The Franklin Court teabowl has the highest SiO2/Al2O3 ratio (=6.5), and the INDE150343 bowl the lowest (=3.5). The silica/alumina ratio of teapot V.213 (=4.8) is 20% higher than that of the Philadelphia bowl (=4.0). The alkali contents in all four samples are low (Na2O+K2O = 1.5-2.6; Table 1, see figs. 13-17), the highest alkali concentration being in the Philadelphia bowl. Their lime contents are low (<1 wt.% CaO).

The glazes on the samples are diverse in terms of their major elements. Most distinctive is the lead-rich (40% PbO), alumina-poor (2.4% Al2O3) glaze on teapot V.213 (Table 1). It has fluxed the ceramic substrate, forming a partly crystallized (K feldspar) integrated body-glaze layer (IBGL) (fig. 10B). Experiments on compositional analogues of the teapot show that a mineralogically and microstructurally-similar ware can be created by firing the paste for 48 hours at 1370oC, and that a K feldspar-bearing IBGL forms during firing for at least 5 hours at 1000oC.[15]

The other three Philadelphia-found samples have high-temperature (e.g., lead-poor; <1000 ppm Pb) compositions with relatively high alumina (11–21% Al2O3) contents. The Franklin Court teabowl has a salt glaze (figs. 10C,10D), with 12% Na2O and <0.5% CaO and K2O.[16] The glaze on bowl INDE150343 contains moderate amounts of lime (3.6% CaO), soda (5.5% CaO), and potash (4.5% K2O), in contrast to the lime-rich (7.8% CaO) glaze on the Philadelphia bowl (fig. 10E). It has partly crystallized, containing ternary feldspar microlites (An21Ab48Or3) (fig. 10F).

Miniature teapot WW003 has an aluminous-silicic body, and, like teapot V.213, a lead-rich (29.9% PbO) glaze. They are separated by an IBGL (fig. 11). The body of the teapot contains about 74 wt.% silica and 21% alumina. It has a low alkali content (Na2O + K2O = 2.4%). The presence of 1% titania and 0.7% iron oxide suggest the presence of Fe(Ti) oxide grains (as impurities) in the clay. The IBGL has concentrations of SiO2, TiO2, Al2O3, and PbO intermediate between those in the glaze and body, but is enriched in alkalis.[17] The glaze is compositionally zoned, showing a rimward decrease in silica, potash, and alumina, and an increase in lead. In addition to lead, it contains about 60% SiO2, 4% Al2O3, ~5% total alkalis (Na2O+K2O), and 1% CaO.

Provenance

Compositional data coupled with aesthetic criteria can be an effective tool in determining the origin (i.e., place of manufacture) of historical ceramic wares, provided that representative analyses are available for bona fide wasters from various potwork sites and/or for documentary ceramic objects. Glaze compositions, however, can vary with firing history, at least with respect to major and minor elements, so emphasis should be placed on paste compositions where they can be obtained. Owing to their mineralogical simplicity, however, aluminous-silicic porcelains show a limited range of compositions in terms of their major- and minor-element concentrations compared with many of their artificial (soft-paste) porcelain counterparts. For example, excluding the Pomona samples, all of which are deeply flawed in character and so probably were experimental wares, the silica and alumina contents of analyzed aluminous-silicic samples presented in Table 1 have a range of 71–80% and 16–20%, respectively. They overlap the silica and alumina contents of both teapot V.213 and the Philadelphia bowl.

Those samples also overlap in their soda (<2% Na2O) and potash (1–3% K2O) contents. Consequently, emphasis is placed here on comparing the trace-element composition of teapot V.213 and the Franklin Court teabowl with eighteenth-century counterparts from Britain and America. The former include aluminous-silicic (-calcic) samples from the Worcester, Limehouse, Pomona, and Brownlow Hill (William Reid) factory sites (see Table 1). Since the V.213 teapot is lead-glazed and was found in Philadelphia close to the location of the American China Manufactory, three samples of lead-glazed phosphatic (soft-paste) Bonnin and Morris porcelain were also analyzed for comparison.

The results are best summarized graphically, using either (a) standard multi-element diagrams normalized against a suitable geochemical standard (e.g., chondritic meteorites), or (b) statistical plots such as principal-component analysis or multidimensional scaling (MDS) diagrams.[18] In this study, MDS diagrams were chosen to compare the samples recovered in Philadelphia with each other and with British counterparts. MDS resembles principal-component analysis except that the results are generally easier to interpret because variance is summarized in fewer dimensions.[19] The MDS diagrams were generated using SYSTAT software.[20] MDS considers all analyzed elements collectively. Samples (or chemical constituents) that are similar, or that behaved similarly during kiln firing, plot close together on MDS diagrams. Points on opposing sides of an MDS diagram, however, represent samples (or chemical constituents) that are dissimilar or behaved differently. These diagrams can thus be used to compare relationships between samples or between the chemical data describing samples, and in this regard have been used to interpret compositional similarities and dissimilarities in a variety of media, including pottery.[21] Here, emphasis is placed on identifying geochemically affiliated groups of porcelain samples, rather than groups of geochemically linked components.

The results for glaze compositions (fig. 12A) show the circular array of points typical of MDS plots. The glazes on early Worcester aluminous--silicic pastes cluster together in the upper left of this diagram, with the lead-rich glazes on phosphatic Bonnin and Morris porcelain plotting together in the upper right, and the glaze on a lead-bearing S-A-C porcelain 1773 Philadelphia basket displaced toward the interior of the diagram, part way toward the position of the glaze on teapot V.213.[22] The glaze on the miniature teapot (WW003) plots among these early Worcester samples, but its paste plots just outside the field defined by the bodies of true porcelain artifacts excavated in Philadelphia (fig, 12B).

The Limehouse glazes form an arc on the right side of the diagram, with sample LM5 plotting very close to the glaze on an A-marked (1st patent Bow) teapot lid.[23] The glazes on the two Cookworthy porcelain figures plot together in the lower right of fig. 12A. The glaze on an aluminous-silicious fragment from the Bartlam site plots by itself in the lower left. Significantly, the salt glaze on the Franklin Court teabowl plots alongside the calcium-rich glaze on the Philadelphia punch bowl, opposite the field of Bonnin and Morris glazes. The position of teapot V.213 glaze intermediate between these samples indicates that its composition is consistent with a blending of both, suggesting that, notwithstanding their diverse compositions, all were made at the same factory.

The MDS plot for ceramic paste compositions (see fig. 10B) shows that the body of teapot V.213, the Franklin Court teabowl, bowl INDE150343, and the Philadelphia punch bowl cluster together with Limehouse sherd LM5 at the left-center, below a field of points for Pomona, Worcester, and Liverpool (William Reid) porcelain, and close to the miniature teapot (WW003). One Pomona paste plots in the upper right of this diagram, near the other Limehouse samples. The three analyzed Bonnin and Morris pastes plot in the right-center, just above the dated 1773 Bonnin and Morris openwork basket and A-marked porcelain (1st patent Bow) teapot lid. The sole Bartlam sherd plots near the two Cookworthy samples at the bottom. The inner and outer parts of mullite-rich melt blebs in the Philadelphia punch bowl plot in the lower left, separate from the overall paste composition of the bowl itself.

The MDS data therefore suggest that teapot V.213, the Philadelphia punch bowl, the INDE150343 bowl, and the Franklin Court teabowl were all made at the same pottery, probably in Philadelphia. A case could be made that the lead-glazed miniature teapot also originated at this unidentified Philadelphian/American factory.

Conclusions

The discovery of the first American true porcelain punch bowl from a privy at the site of the Museum of the American Revolution in Philadelphia not only introduced a previously unknown ceramic type to the timeline of American ceramic production, but also initiated a race to find additional archaeological and intact examples. The three examples discussed here—the blue-and-white decorated teapot (V.213) from the MOAR site, an undecorated teabowl from Franklin Court, and an undecorated bowl (INDE150343) from the National Constitution Center site on Independence Mall—all share the same compositional characteristics as the first punch bowl, which suggests they share an American origin. The miniature teapot has similar qualities as known American porcelain objects, particularly the decoration, which is reminiscent of that found on Bonnin and Morris examples.

Although all four artifacts have aluminous-silicious pastes, their glazes have a range of major-element compositions.[24] The glaze on the Philadelphia bowl is relatively calcic, whereas the teapot glaze is lead-rich; the Franklin Court teabowl glaze is relatively sodic, and probably a salt-glaze; and the INDE150343 bowl glaze contains moderate amounts of lime, soda, and potash. Despite this, the three low-lead glazes cluster together on a statistical plot that simultaneously compares their concentrations of 46 components (8 major/minor components, and 38 high-precision trace elements). Except for one sample, they are distinct from the glazes on most contemporary hard-paste wares from Britain: Worcester (stone china from the Warmstry House site), Pomona (Staffordshire), Reid (Brownlow Hill, Liverpool, and Cookworthy porcelain), Limehouse (London). Moreover, their pastes cluster together on an analogous plot for porcelain bodies. These results suggest that all three archaeological vessels were made at the same manufactory in Philadelphia. Based on the composition of its paste, the lead-glazed miniature teapot found in Britain might also have originated at the same factory as those excavated in Philadelphia.

The question of who made these porcelains has yet to be answered. It is fairly certain that they were made in Philadelphia sometime in the decade before the start of the American Revolution. Alexander Bartram, with his “Pennsylvania penciled tea pots, bowls and sugar dishes,” is a compelling prospect given that he is unknown in the annals of American ceramic history. However, the evidence of a pottery that was operated and/or financed by him is extremely limited and provides no detailed information.[25] Similarly compelling is the factory of Bonnin and Morris, whose well-known soft-paste porcelains have been at the forefront of early American ceramic scholarship for decades. Yet, there is no definitive proof, either written or from excavations at the site of their pottery, that they were making true porcelain. Conceivably there were other partnerships, specifically between Andrew and possibly his brother, Anthony II, who worked as a potter in the Duché family pottery, and either Bonnin and Morris or Alexander Bartram. After three decades in the Southern colonies and England, Andrew Duché returned to Philadelphia in 1769, the year before Bonnin and Morris began operations. His knowledge of porcelain manufacture from his time in South Carolina and Georgia would have made him particularly valuable to an upstart porcelain factory led by young, inexperienced entrepreneurs. In terms of Bartram, Anthony Duché II owned considerable property in Southwark, including a lot on what is now the same block as one owned by Bartram, and several additional lots to the rear of Bartram’s property and pottery.[26] Bartram himself was not a potter but certainly needed one to run his operation. Could it have been Duché? Bartram’s pottery was also only two-tenths of a mile from Bonnin and Morris’s factory. Could Bartram, the Duchés, and Bonnin and Morris have worked together on the production of America’s first porcelain? One compelling find of this study is that one of the vessels, the teabowl from Franklin Court, is a porcelain body with a salt glaze. This suggests, if not proves, that the Duchés had their hand in either the Bartram or the Bonnin and Morris operations. The story continues.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Fragments from teapot V.213, the Franklin Court teabowl, and the INDE150343 bowl were made available for analysis courtesy of Independence National Historical Park. The sample and description of teapot WW003 were provided by Clare Durham. We thank Rod Jellicoe for his comments concerning the similarity of teapot V.213 with Liverpool examples. We also thank Randolph Corney for preparing at short notice the carbon-coated polished slides of our samples, and for drafting services. Xiang Yang ensured that the SEM ran smoothly. This paper was supported by funds made available by the Chipstone Foundation.

This inference is based on the discovery of lead-glazed phosphatic porcelain sherds at the Bartlam factory site. However, porcelain wasters and porcelain fused on saggars have yet to be recovered from this site, leaving the possibility, however remote, that the porcelain sherds might have been produced elsewhere. The hypothesis that phosphatic porcelain from the Cain Hoy site was manufactured near where it was found is supported by similarities in the trace element signature of the glazes on both earthenware (creamware) and porcelain sherds from this locality (see J. Victor Owen, Jacob J. Hanley, and Joseph A. Petrus, “Phosphatic Alteration of Lead-Rich Glazes during Two Centuries of Burial: Bartlam, Bonnin & Morris, and Chelsea Porcelains,” Archaeological and Anthropological Science, https://doi.org/10.1007

/s12520-019-00922-4). For background on Bartlam at Cain Hoy, see Stanley South, “John Bartlam’s Porcelain at Cain Hoy, 1765–1770,” in Ceramics in America, ed. Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2007), pp. 196–203; Lisa R. Hudgins, “John Bartlam’s Porcelain at Cain Hoy: A Closer Look,” in ibid., pp. 203–8.

Robert Hunter and Juliette Gerhardt, “An Eighteenth-Century American True-Porcelain Punch Bowl,” in Ceramics in America, ed. Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2016), pp. 179–99.

J. Victor Owen, Joe Petrus, and Xiang Yang, “Bonnin and Morris Revisited: The Geochemistry of a True-Porcelain Punch Bowl Excavated in Philadelphia,” in Ceramics in America, ed. Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2016), pp. 179–99.

Graham Hood, “The Career of Andrew Duché,” Art Quarterly 31 (1968): 168–84. Bradford L. Rauschenberg, “Andrew Duche: A Potter ‘a Little Too Much Addicted to Politicks,’” Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts 17, no. 1 (May 1991): 1–101.

Hunter and Gerhardt, “An Eighteenth-Century American True-Porcelain Punch Bowl.”

Advertisement, Pennsylvania Gazette, March 9, 1767.

Bartram’s loyalty to the British crown led to the confiscation of his estate by the Continental Congress sometime before 1776. An inventory of Bartram’s estate taken that same year notes “Sundry Buildings, built &occupied for a Pott House” in Southwark on “48 ft. [fronting] Shippen Street and 100 feet on 3d Street compleat for sd Business, empty.” As quoted in, “Forfeited Estates: Inventories and Sales,” ed. Thomas Lynch Montgomery, Pennsylvania Archives, 6th ser. (Harrisburg: Harrisburg Publishing Company, 1907), 12:605.

Rebecca Yamin, Principal Investigator, with contributions by Tod L. Benedict, Meagan Ratini, Kevin C. Bradley, Leslie E. Raymer, Juliette Gerhardt, Kathryn Wood, Timothy Mancl, and Claudia L. Milne, Archaeology of the City—The Museum of the American Revolution Site Archaeological Data Recovery, Third and Chestnut Streets, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 2 vols. (West Chester, Pa.: Commonwealth Heritage Group, 2016), vol. 1.

Betty Cousans, “Franklin Court Report, Vols. 1–6 (1974),” unpublished manuscript, Independence National Historical Park, Philadelphia.

The artifacts excavated at Franklin Court were last analyzed in the early 1980s. At the time of the analysis, little was known about local production of refined ceramics in Philadelphia. Reassessment of the collection likely would reveal previously unidentified examples of Bonnin and Morris and American true porcelain.

Research in progress by Deborah Miller.

A memorandum dated July 12, 2018 by J. Victor Owen to Deborah Miller lists the results of the analysis of the dish’s body as “soapstone porcelain” e.g. Worcester

Philip Christian and Son (ca. 1769–78) often copied Worcester patterns and forms. For more information, see Geoffrey A. Godden, Godden’s Guide To English Blue and White Porcelain (Woodbridge, Eng.: Antique Collectors’ Club, 2004), pp. 343–47.

Personal communication with J. Victor Owen August 2017.

Evan M. Owen, J. Victor Owen, Joseph J. Hanley, and Nicole Kennedy, “Development of an Integrated Body-Glaze Layer on an 18th Century Lead-glazed True Porcelain Teapot from Philadelphia: Insights from Kiln Firing Experiments on Compositional Analogues,” Historical Archaeology 52, no. 3 (2018): 617–26.

See Frank Hamer and Janet Hamer, The Potter’s Dictionary of Materials and Techniques, rev. ed. (1975; New York: Watson-Guptill, 1986).

See Evan M. Owen et al., “Development of an Integrated Body-Glaze Layer on an 18th Century Lead-glazed True Porcelain Teapot from Philadelphia.”

Ingwer Borg and Patrick J. F. Groenen, Modern Multidimensional Scaling: Theory and Applications (New York: Springer, 1997).

Leland Wilkinson et al., SYSTAT for Windows: Statistics, Version 5 Edition (Evanston, Ill.: SYSTAT, 1992).

Ibid.

See, for example, J. Victor Owen, Joanna L. Casey, John D. Greenough, and Dorothy Godfrey-Smith, D. “Mineralogical and Geochemical Constraints on the Sediment Sources of Late Stone Age Pottery from the Birimi Site, Northern Ghana,” Geoarchaeology 28, no. 4 (2013): 394–411; and J. Victor Owen, John D. Greenough, Meagan Himmelman, and Stephen T. Powell, “Geochemistry of Pre-Contact Potsherds from Southern Mainland Nova Scotia: Constraints on Pottery Pathways,” Canadian Journal of Archaeology 40, no. 2 (2016): 231–67.

J .Victor Owen and Robert Hunter, “Too Little, Too Late: The Geochemistry of a 1773 Philadelphia Openwork Porcelain Basket,” Journal of Archaeological Sciences 36, no. 2 (2009): 333–42.

J. Victor Owen, “Double Corona Structures in 18th Century Porcelain (1st Patent Bow, London, mid-1740s): A Record of Partial Melting and Subsolidus Reactions,” The Canadian Mineralogist 50, no. 5 (October 2012): 1255–64.

J. Victor Owen, “A New Classification Scheme for Eighteenth-Century American and British Soft-Paste Porcelain,” Ceramics in America, ed. Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2007), pp. 121–40.

Bartram, a Tory, abandoned his property and his family when he left Philadelphia with the British Army in April 1777. His lots on Second Street, where the pottery was located, were sold in August 1779 to artist Charles Willson Peale he inflated price of £7,000. For more information, see Wayne Bodle, “Jane Bartram’s ‘Application’: Her Struggle for Survival, Stability, and Self-Determination in Revolutionary Philadelphia,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 115, no. 2 (1991): 185–220.

Numerous deeds for Anthony Duché, Alexander Bartram, and Bonnin and Morris were studied to determine the locations of their properties/potteries. All were accessed online through a subscription service sponsored by the City of Philadelphia at www.phila.gov/records/DocumentRecording/OnlineAccess.html. One additional digital resource, http://maps.archives.upenn.edu/WestPhila1777/map.php, was used continuously throughout this process to ensure accuracy of details relating to the real-estate holdings of those in question.