Teabowl fragment, John Bartlam, Cain Hoy, South Carolina, 1765–1770. Soft-paste porcelain. H. of fragment 1 7/16". (The Charleston Museum; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The lead glaze on this archaeologically retrieved teabowl fragment has degraded, and portions were physically scraped away to reveal the underglaze decoration.

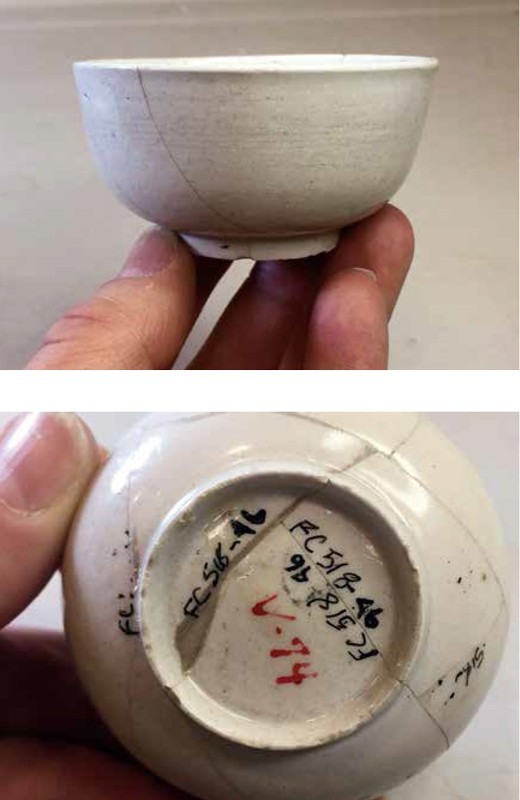

Saucer, American China Manufactory, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1770–1772. Soft-paste porcelain. D. 5 1/8". (Courtesy, Independence National Historical Park; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This example of a Bonnin and Morris saucer has hand-painted chinoiserie decoration (left). No antique examples of any of the teawares are known to survive, although they are mentioned in the documents of the factory. Note the distinctive “P” for “Philadelphia” mark (right), which has been found on virtually every known example of Bonnin and Morris. Like the Bartlam ware illustrated in figure 1, the lead glaze on these phosphatic bodies degrades chemically and reacts with soil when buried in the ground, creating the crusty, brown surface.

Punch bowl, attributed to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1772. Hard-paste porcelain. D. 5 1/2". (Courtesy, The Museum of the American Revolution; photo, Robert Hunter.) Recovered in 2014 from among nearly 85,000 artifacts found on the site of the new Museum of the American Revolution by archaeologists from Commonwealth Heritage Group, this bowl was initially thought to have a stoneware body. However, subsequent material analysis by Victor Owen and his colleagues revealed that it is true porcelain, and most likely had been manufactured in Philadelphia.

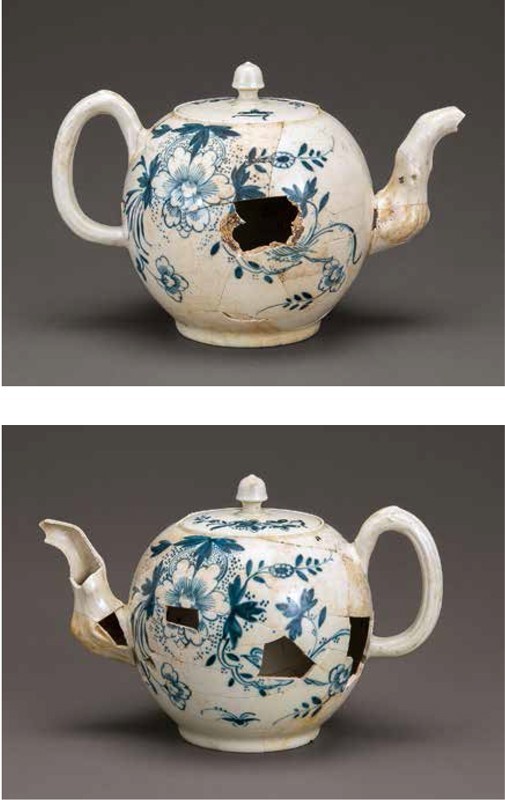

Teapot, attributed to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1767–1772. Hard-paste porcelain with a lead glaze. D. 5 1/2". (Courtesy, The Museum of the American Revolution; photo, Robert Hunter.) This newly analyzed decorated teapot has a hard-paste body related to the punch bowl illustrated in fig. 3. It was lead glazed, however, and decorated with brushed cobalt. Historical research suggests that this teapot may relate to an advertisement placed in 1767 in the Pennsylvania Gazette by Scottish immigrant merchant Alexander Bartram, which describes “Pennsylvania penciled teapots.” The date, of course, precedes the 1770 opening of the American China Manufactory owned by Gousse Bonnin and George Anthony Morris.

Teabowl, attributed to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1772. Hard-paste porcelain. D. 2 3/4". (Courtesy, Independence National Historical Park; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Punch bowl, attributed to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1772. Hard-paste porcelain. D. 5 1/2". (Courtesy, Independence National Historical Park; photo, Robert Hunter.) This undecorated small punch bowl is very similar to the example illustrated in fig. 1. It was recovered from a late-eighteenth-century privy deposit among a wide range of refined English earthenware and Chinese porcelain. Also found in association were two marked Bonnin and Morris porcelain sauceboats. INDE150343

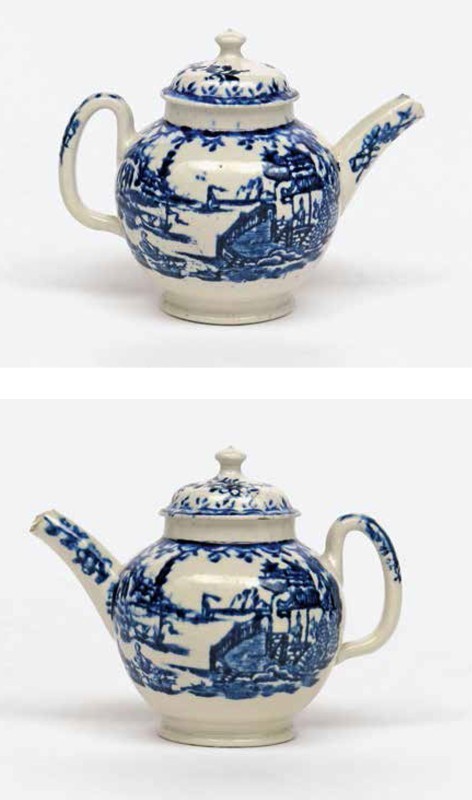

Miniature or toy teapot, Britain or America, ca. 1767–1770. Hard‑paste porcelain. H. 3 15/16". (Photo courtesy of Clare Durham, Woolley and Wallis Auctions.)

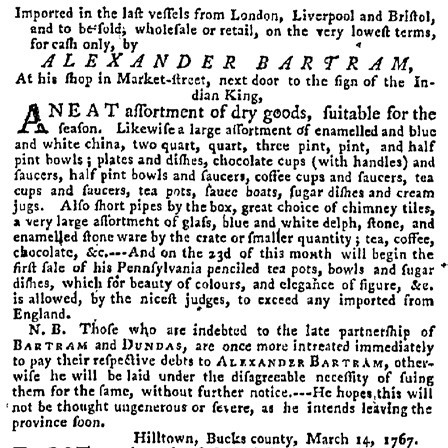

Advertisement placed by Alexander Bartram in the Pennsylvania Gazette, March 9, 1767.

Detail of the teabowl illustrated in fig. 5, showing the glaze inclusions.

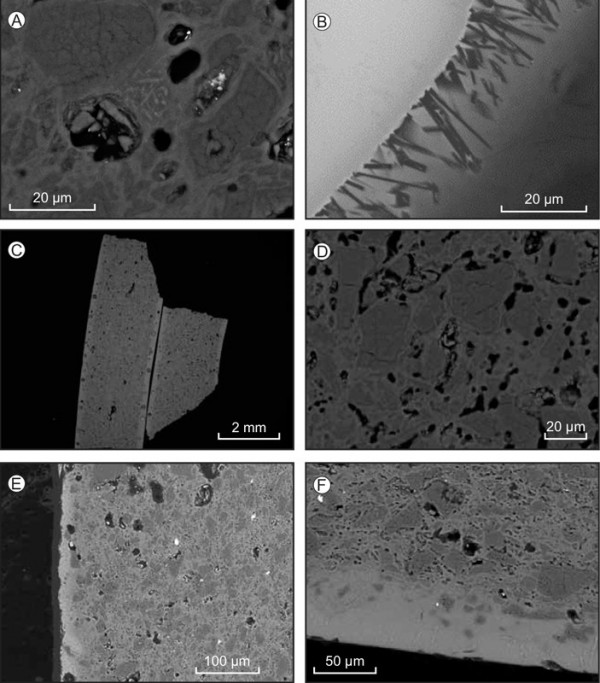

Backscattered-electron images: (A) the body of teapot V.213 showing mullite microlites (pale-gray needles in center of image); (B) its partly crystallized (K feldspar), integrated body‑glaze layer and the overlying lead-rich glaze; (C) overview of two fragments of the Franklin Court teabowl showing its salt glaze; (D) close-up of teabowl body showing an interstitial melt phase (pale gray) partly corroding silica polymorphs (probably α-quartz; medium gray); (E) the body and calcium-rich glaze (the narrow, pale gray, shown on the left of the image) of the Philadelphia bowl; and (F) a close-up of the body and partly crystallized (ternary feldspar [slender, white grains]) glaze on the bowl illustrated in fig. 6. Irregular medium-gray grains entrained by the glaze are silica polymorphs (probably α-quartz) from the ceramic substrate. The black patches in A, B, D, E, and F are pores.

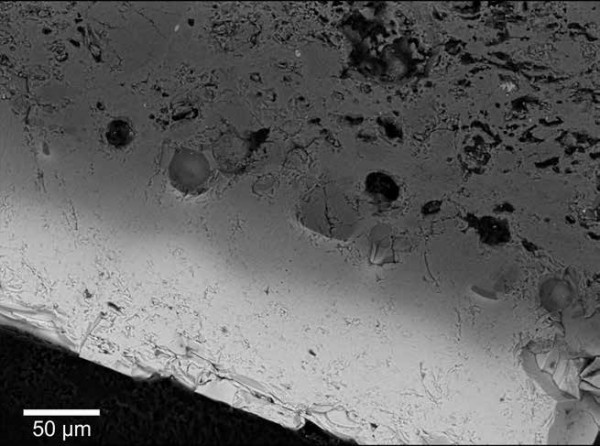

Backscattered-electron image showing the integrated body-glaze layer (medium-gray band) separating the lead-rich glaze (lower left) from the body (upper right) of the miniature teapot illustrated in fig. 7.

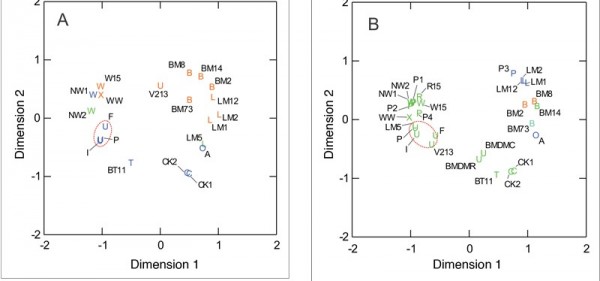

MDS diagrams for (A) glaze, and (B) paste compositions of teapot V.213, the Franklin Court teabowl (“F”), and the Philadelphia bowl (“P”) (all represented by the “U” symbols), together with aluminous-silicic porcelain sherds from the John Bartlam (“T”), and Worcester (“W”) sites, and intact Cookworthy (“Ck”) porcelain figures, and aluminous-silicic to S-A-C- porcelain sherds from the Limehouse (“LM”) and Bow (“A”-marked [first patent]; “O”) factory sites, and experimental, lead-bearing S-A-C porcelain from Pomona (“P”), Staffordshire. The lead-glazed true porcelain miniature teapot (see fig. 7) found in the UK is denoted by an “X.” Also plotted, for comparative purposes, are the compositions of phosphatic porcelain sherds from the Bonnin and Morris (“B”) site, and the composition of a zoned, mullite-bearing melt bleb (“BMDMR [rim] and BMDMC [core]”) in the Philadelphia punch bowl. Sample numbers are indicated. Note the clustering (red dashed fields) of key aluminous-silicic samples excavated in Philadelphia (see text). Colors distinguish the lead content of glazes—blue: low lead (<5,000 ppm Pb), green: medium lead (5,000–15,000 ppm Pb) and orange: high lead (>15,000 ppm Pb)—and paste compositions (green: aluminous‑silicic; orange: phosphatic; blue: S-A-C; turquoise: Pb-bearing S-A-C) in figures (A) and (B), respectively.

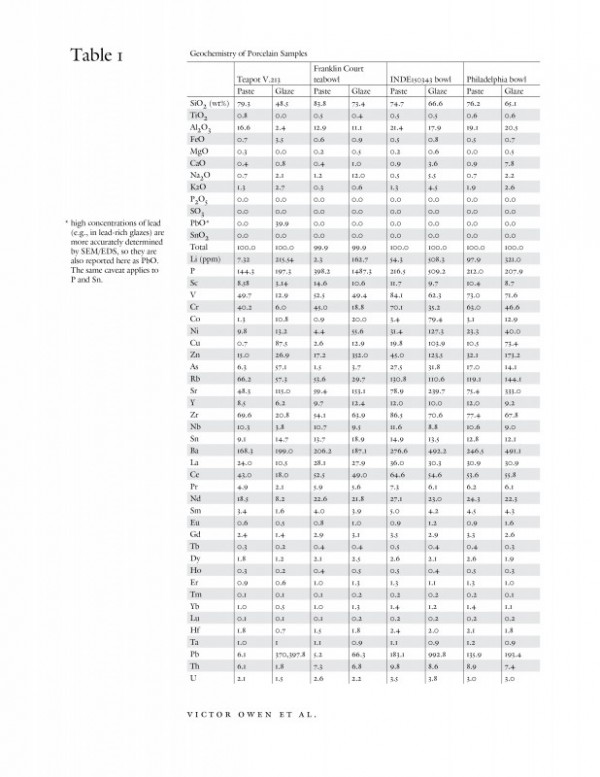

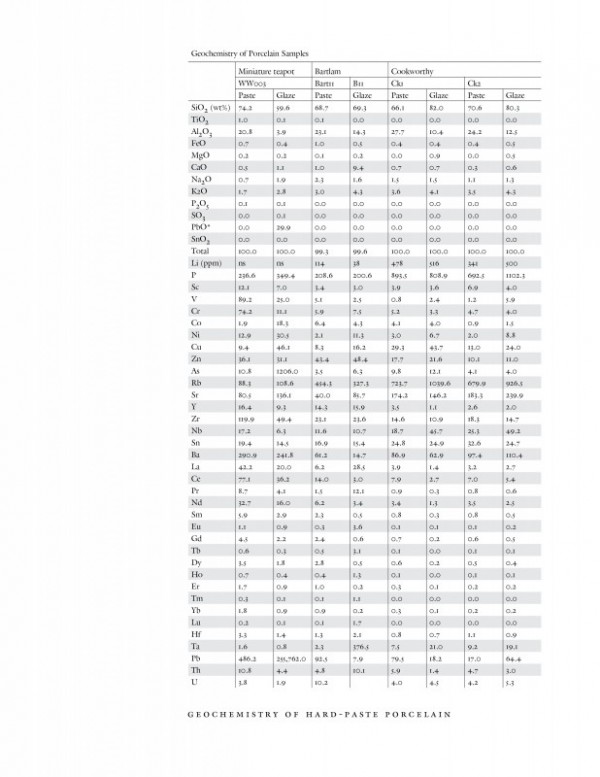

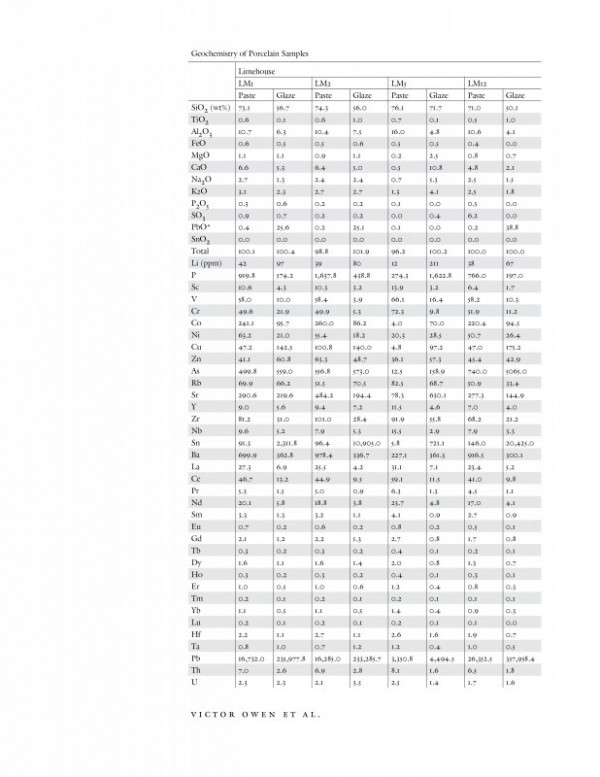

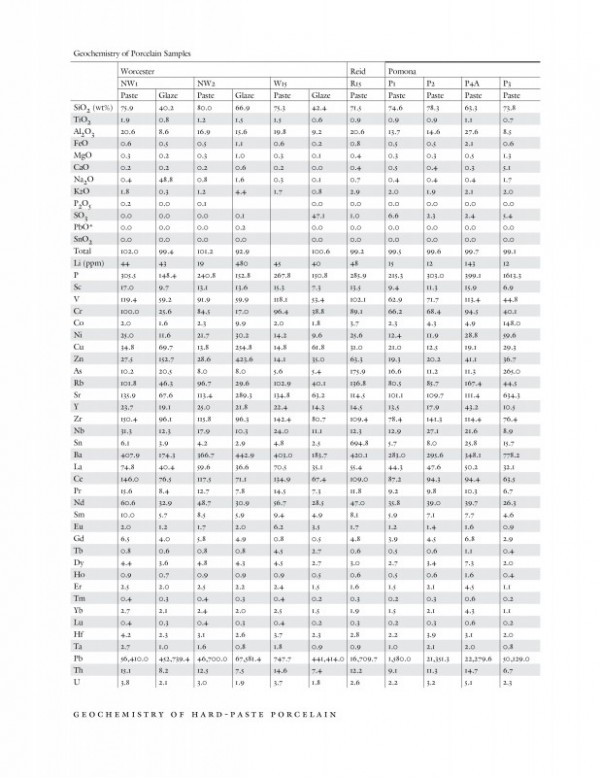

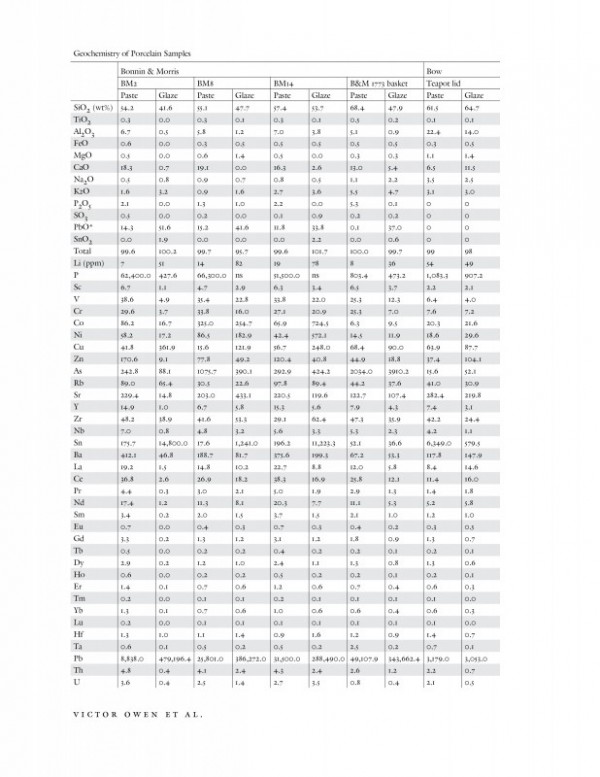

Table Geochemistry of Porcelain Samples

Table Geochemistry of Porcelain Samples

Table Geochemistry of Porcelain Samples

Table Geochemistry of Porcelain Samples

Table Geochemistry of Porcelain Samples