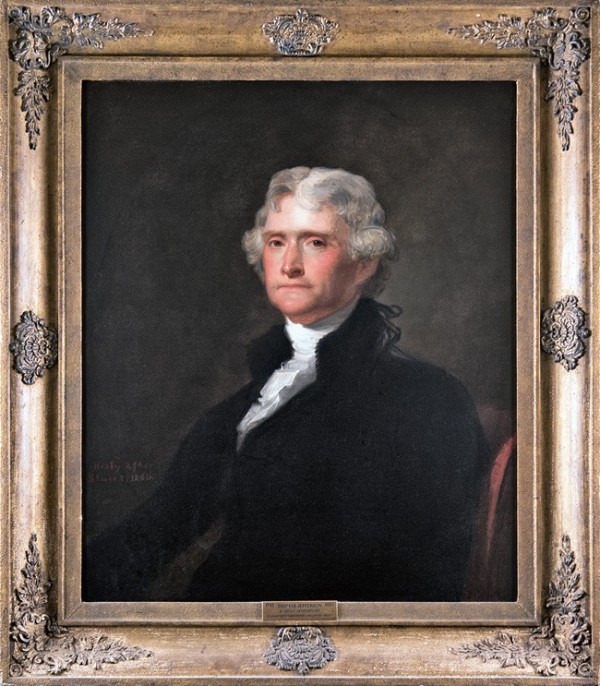

George Healy (1813–1894), after Gilbert Stuart (1755–1828), Portrait of Thomas Jefferson, 1860. Oil on canvas. 29 1/2 x 24 1/2". (Museums at Washington and Lee University.)

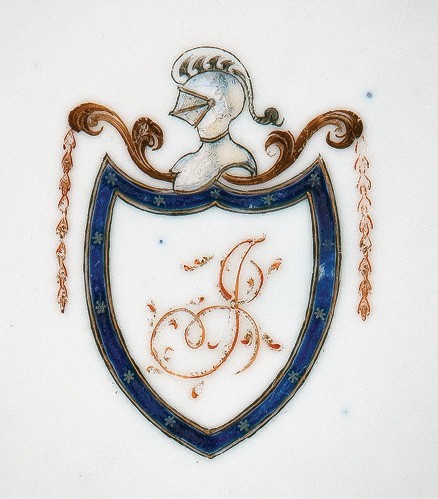

Pot de crème from the “J” service, Jingdezhen, decorated in Guangzhou (Canton), China, 1790–1792. Hard-paste porcelain. H. 3". (Courtesy, Sandy and Ched Cluthe Collection.)

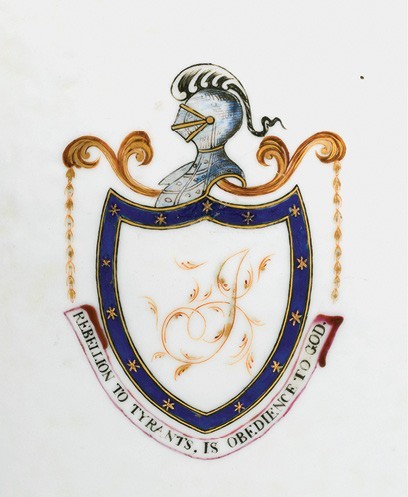

Plate from the “J” service, Jingdezhen, decorated in Guangzhou (Canton), China, 1790–1792. Hard-paste porcelain. D. 9 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Detail of the plate illustrated in fig. 3.

Jug from the “J” service, Jingdezhen, decorated in Guangzhou (Canton), China, 1790–1792. Hard-paste porcelain. H. 9 1/4". (Courtesy, Cincinnati Art Museum.)

Detail of the jug illustrated in fig. 5.

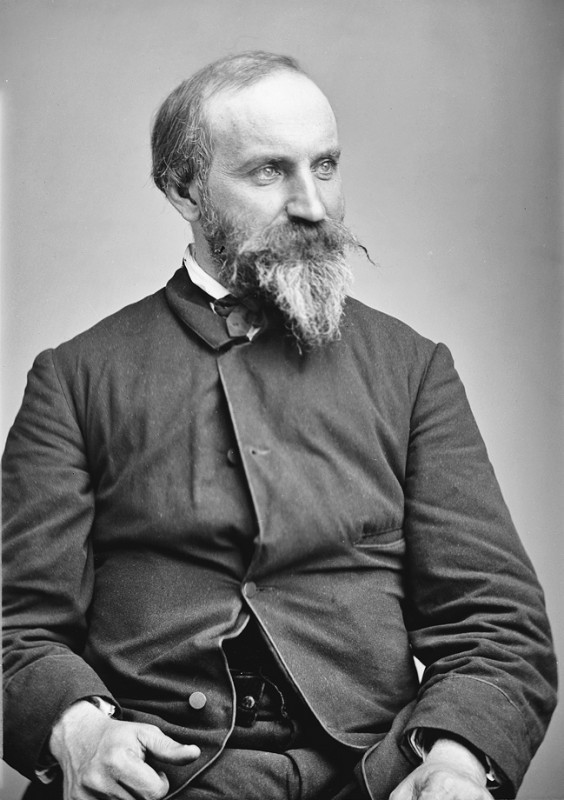

Caleb Lyon, ca. 1855–1865. (Brady-Handy Collection, Library of Congress.) https://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/cwpbh.01858

Cup from the service made for Christopher Gore, Jingdezhen, decorated in Guangzhou (Canton), China, 1790–1792. Hard-paste porcelain. H. 2 3/4". (Courtesy, Sandy and Ched Cluthe Collection.)

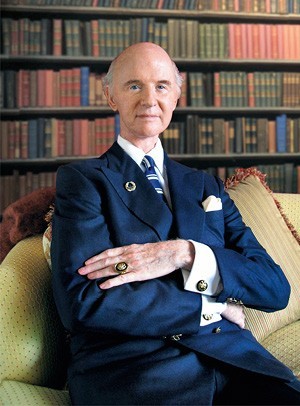

Raleigh DeGeer Amyx, 2009. (Courtesy, The Raleigh DeGeer Amyx Collection.) http://www.americanheritage1.com/.

Bowl from the “WMP” service, Jingdezhen, decorated in Guangzhou (Canton), China, 1790–1792. Hard-paste porcelain. D. 9 5/8". (Private collection; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Detail of the bowl illustrated in fig. 10.

Teapot, Josiah Wedgwood & Sons, Ltd., Staffordshire, England, ca. 1871. Creamware. L. 8 1/4". This reproduction of Lyon’s “Elder Brewster Teapot” was commissioned by the Boston retailer Richard Briggs & Co. (Private collection; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Detail of the teapot illustrated in figure 12.

On October 24, 1858, Mrs. Joseph Coolidge of Cambridge, Massachusetts, observed in a letter to her husband that “it is difficult to prove a negative.”[1] Mrs. Coolidge’s letter constituted a passionate defense of Thomas Jefferson, her maternal grandfather, against persistent claims that he had fathered children with one of his enslaved women.

Her evidence included confirmation by her brother, “then a young man certain to know all that was going on behind the scenes, [who] . . . solemnly affirms that he never saw or heard the smallest thing which could lead him to suspect that his grandfather’s life was other than perfectly pure.”[2] Given that recent scholarship has confirmed Jefferson’s relationship with Sally Hemmings, there was clearly more going on behind the scenes than the rest of the family might have been aware of or wanted to admit. Family histories are often strongly influenced by wishful thinking. Memories fade and facts blur with the passage of time. Ironically, more than 150 years after writing that letter, Mrs. Coolidge, born Eleonora “Ellen” Wayles Randolph, is again a key figure in persistent claims that a Chinese-export porcelain service decorated with a shield bearing the initial “J” belonged to Thomas Jefferson (figs. 2–4). Plates, platters, and other serving dishes, as well as a jug that bears a motto beneath the shield “rebellion to tyrants, is obedience to god,” are known (figs. 5, 6). In this article I refer to them collectively as the “J” service. Armed with a few facts supplemented with sketchy logic and wishful thinking, throughout the past century and a half some collectors, auction houses, and dealers have advanced the claim that Jefferson owned and used the “J” service at Monticello or the White House or both. Scholars and museum curators have consistently acknowledged these claims, but often with some skepticism. Pesky questions draw unsatisfying answers. As Jefferson’s granddaughter observed, proving a negative is difficult, but that is precisely the goal of this article. An examination of the claims made about the “J” service in the marketplace, an overview of the published scholarship, and an analysis of primary source documents, including Jefferson’s correspondence and ledgers, along with other firsthand accounts, will demonstrate that while the “J” service was in fact ordered for Thomas Jefferson, he did not own it and he did not use it.

The public claims that the service belonged to Jefferson date back to at least 1876. On April 24 of that year, New York auctioneer Henry D. Miner auctioned the “Governor Lyon Collection of Ceramics.”[3] The catalog introduction noted: “It was Governor Lyon’s ambition to have a small collection of rare old interesting specimens, rather than a large number of ordinary pieces: and a peculiar feature of his collecting was to always endeavor to procure pieces that had some history attached to them—some incident that gave them another value and charm save their own intrinsic worth.[4]” In keeping with that description, the auction included a section beginning with lot 823 under the heading “Presidential Porcelain.” The catalog proclaimed: “The following porcelain has been used by the different Presidents and includes specimens from all the sets purchased by Congress at times to refurnish the White House; some of the Presidents provided their own china, or used that which was left by their predecessors in office.”[5] Lot 850, beneath the heading “President Jefferson” is described as follows: “A splendid plate of Chinese manufacture with rim and inner border diapered in dark blue relieved by gold tracery. In the centre the letter ‘J’ in gold is enclosed in a shield, the outline of which is of blue enamel adorned by the thirteen stars. A helmet with visor closed, in light blue, surmounts the shield.”[6] Unquestionably the Lyon catalog describes a plate from the “J” service, and Caleb Lyon (fig. 7) is a central character in the story of the “J” service. The Lyon auction was well advertised not only in New York but also in Boston and Philadelphia. The April 15, 1876, edition of the Boston Post included a notice of the “Important Sale of the Lyon Collection of Ceramic Ware.”[7] The Philadelphia Times contained a more dismissive announcement: “Governor Lyon was one of the earliest china maniacs in this country, and his collection . . . includes some rubbish, interesting for its associations only.”[8] James Grant Wilson mentioned the Caleb Lyon sale in his article “About Bric-à-Brac,” published in the Art Journal in 1878. Wilson observed that “the fashion of forming collections of bric-à-brac is rapidly increasing in this country. Old china, which once may have been valuable as heirlooms, but not otherwise, is now brought out and sold at fabulous prices to bric-à-bracqueurs.”[9] He further noted that “the only American sales of bric-à-brac of importance that I happen to remember at the moment are the collections of the eccentric John Allan and the late Caleb Lyon, of Lyondale—the latter sold in this city in April 1876.”[10] Subsequent treatment of the “J” service has taken two very different trajectories. Most scholars—including Alice Morse Earle, Marian Klamkin, Jean McClure Mudge, and Margaret Brown Klapthor—have been skeptical of the claims in the Lyon catalog that Jefferson owned the service, but few have refuted it entirely.[11] David Sanctuary Howard included the “J” service in his second volume of Chinese Armorial Porcelain, but he cautiously titled the entry “Jefferson ?” Dating the service to circa 1790, he observed that “although this service has been associated with Thomas Jefferson, there appears to be no evidence that it was in his possession during his lifetime.”[12] In contrast to the published scholarship, the trade has often followed the Lyon catalog’s attribution. Most recently, a number of pieces that descended in the Coolidge family were sold through Christies, which carefully noted that the pieces were property of a direct descendant of Thomas Jefferson and proclaimed them to be from “the ‘Thomas Jefferson’ Chinese Export Dinner Service” and that the service was “strongly linked to Thomas Jefferson.”[13] The Christie’s cataloging brings the Coolidges back into the story. The aforementioned Joseph and Ellen Wayles Randolph Coolidge produced a son fittingly named Thomas Jefferson Coolidge (1821–1920). In the late nineteenth century he acquired pieces of the “J” service and, according to some accounts, may have believed that his ancestor Thomas Jefferson had owned the service.[14] In 1906 the Coolidge family donated four pieces from the “J” service to the White House. The New York Times reported that “through the generosity of L. [sic] Jefferson Coolidge of Boston, a valuable addition has been made to the White House collection of Presidential china, consisting of four pieces of Jefferson ware.”[15] Those pieces remain in the White House collection to this day. The Coolidges also loaned pieces to various institutions, among them Monticello. Family members who consigned parts of the service to Christie’s noted that family history recorded, “Ellen’s grandson is the family member who re-acquired the service. Ellen was alive during much of this grandson’s youth; when his son lent the service to public collections at the turn of the [twentieth] century he relayed the family’s history with and knowledge of the service.”[16] These assertions invited the reader to connect dots that are in fact somewhat far apart. The intended inference was that Ellen Randolph told her Coolidge descendants that the “J” service belonged to her grandfather. This theory is based on well-established facts, even if the conclusion does not necessarily follow from those facts. Ellen Randolph spent much of her youth at Monticello, and she corresponded regularly with her grandfather even after her marriage. If Jefferson had used the “J” service at Monticello, she undoubtedly would have seen it and probably would have used it. Another piece of evidence often cited that links the service to Jefferson is a cider jug now in the collection of the Cincinnati Art Museum. It came to the museum with a Quincy family tradition that Jefferson had given the jug to John Adams, and that the jug descended through the Adams family to Mary Adams Quincy.[17] Yet another theory about the service’s origin involves Christopher Gore, a Massachusetts politician. He had a service that is essentially identical, only with a “G” instead of a “J” (fig. 8) Some have suggested that Gore, or his wife, ordered the two services, one for themselves and one to be presented to Jefferson, perhaps to celebrate his 1800 election to the Presidency.[18] Pieces from the “J” service have subsequently appeared at other auctions and dealers throughout the 2010s, all suggesting at least some part of the Jefferson attribution.[19] The person who has most actively promoted the notion that Jefferson owned the “J” service is the late Raleigh DeGeer Amyx (1938–2019), a voracious collector very much in the tradition of Caleb Lyon (fig. 9). Through his own website, a self-published e-book, and “press releases,” Amyx strategically linked known facts together with inferences in an effort to convince readers that Jefferson actually owned the “J” service. There is no doubt that Amyx, like Lyon a century before him, owned an impressive collection of ceramics. However, both men engaged in wishful thinking. A review of Amyx’s claims helps bring his strategy into focus. On June 11, 2013, Amyx posted a “press release” on prweb.com, a website that allows anyone to post information. Amyx authored the release, which he titled “Thomas Jefferson circa 1790’s China Acquired by The Raleigh DeGeer Amyx Collection.” The release announces that “Renowned collector Raleigh DeGeer Amyx recently acquired Chinese export china that was part of the circa 1790s collection owned by President Thomas Jefferson, used at Monticello.”[20] Amyx described acquiring “a number of stunning pieces . . . including ‘dinner plates, soup bowls, a serving bowl, a serving tureen and cover, sauce-boats with leaf-shaped saucers.’”[21] According to Amyx, the service “had been sold after Jefferson’s death to pay his debts but his descendants knew of it and, well over 100 years ago, they were finally able to locate it and reacquire it.”[22] Amyx attempted to bolster the claim that Jefferson owned the “J” service in an e-book he published, The Raleigh DeGeer Amyx Collection: White House China 18th & 19th Century. He included much of the Christie’s catalog description and invoked Ellen Randolph Coolidge, claiming that she had shared with her descendants the family history of the “J” service. He also pointed out the very similar Gore service and repeated the suggestion that the Gores may have purchased the “J” service for Jefferson as a gift. Similarly, Amyx implied that the wives of various twentieth-century presidents support his claim. He observed that Lady Bird Johnson mentioned the “J” service in public remarks in 1964 and that “there are also photographs of First Lady Betty Ford and First Lady Roslyn Carter near/with the Thomas Jefferson “M” [sic] Presidential China, in our modern White House.”[23] Lady Bird Johnson, Roslyn Carter, and Betty Ford were remarkable First Ladies, but the fact that they mentioned or stood near the pieces of the “J” service that the Coolidge family donated to the White House in 1906 lends no credibility to Amyx’s claims. Amyx relies on the Quincy family history mentioned in the 1946 auction catalog to link the “J” service to Jefferson through John Adams: “Jefferson probably gifted one of his cider jugs to his old friend, John Adams. Thus the ‘J’ cider jug that descended through the Adams family, until it was to ultimately reside in 1956, in The Cincinnatti [sic] Museum of Art. This same cider jug resides in same Museum as of 2013.”[24] The avid collectors Caleb Lyon and Raleigh DeGeer Amyx both claimed—and probably believed—that Thomas Jefferson owned and used the “J” service. However, their conclusions rest on shaky factual foundations, and several pesky questions remain unanswered.

In 1985 Christie’s London auctioned a bottle of wine that purportedly had belonged to Thomas Jefferson. The buyer later learned that the bottle had been faked. Writing about the fraud perpetrated on optimistic wine buyers, and the ways evidence had been fabricated and linked with known facts and wild hypotheses, author and researcher Benjamin Wallace observed, “A standard of plausible confirmability had been met.”[25] The same could be said for the “J” service. There is additional evidence that the “J” service never belonged to Jefferson. If it had, why has no trace of it been found in any archaeological excavations at Monticello? If the “J” service was sold in the auction at Monticello in 1827, who bought it? Most of the purchasers at that auction were family members and neighbors, so why did nearly all of the known pieces show up in Boston? Moreover, if Ellen Randolph Coolidge had any knowledge of the “J” service, why did she never make any written mention of it? If Jefferson gave John Adams the Cincinnati Art Museum’s cider jug from the “J” service, why did neither man mention it in his profuse correspondence? Why would Christopher Gore have ordered the “J” service for Jefferson? The two men were aligned at opposite ends of the political spectrum. As with the Adams theory, one would expect such a generous gift to have been mentioned in correspondence or other written records, but no mention of it can be found in the correspondence or records of John Adams and Christopher Gore. Furthermore, what of the third, similar service with the initials “WMP” in the center of the shield (fig. 10, 11)?[26] Did the Gores order all three services? Is the identical design on the services merely a coincidence? Further, the Gore Place Foundation believes that the Gores acquired their “G” service between 1790 and 1796.[27] If that time frame is correct, the theory that they purchased the “J” service for Jefferson to commemorate his election to the Presidency in 1800 comes into question. The service has not been included in any of the publications in which one might expect; it is not included in either edition of Margaret Klapthor’s Official White House China (1999 and 2016), and, while Monticello has displayed pieces of the “J” service from time to time, Susan R. Stein’s comprehensive workThe Worlds of Thomas Jefferson at Monticello makes no reference to the “J” service. Stein wrote, “It would appear that Jefferson, like most who ordered stock Chinese porcelain in the eighteenth century, relied on the tenacity of the middleman, and the nature of the current inventory in China.”[28] Was the attribution in the 1876 Lyon catalog credible? Few scholars have carefully evaluated the 1876 description of the “J” service in the Lyon sale. The auction catalog appears to be the first published claim that Jefferson owned the “J” service. Some investigation of his background suggests that the credibility of that attribution is weak. Caleb Lyon was one of the first prominent collectors of ceramics in the United States. He was a United States congressman from New York in the 1850s, and President Lincoln later appointed him to the post of governor of the Idaho Territory. Lyon thus enjoyed a veneer of respectability.[29] A few more details paint a colorful image of this collector and provide insight into objects that can trace their provenance to him. According to one historian, Lyon was recognizable “by always appearing with a flaming neck-tie and curiously grotesque clothes,”[30] which included “a plaid silk cravat, monkey jacket, and green and black pants.”[31] The New York Daily Herald similarly referenced Lyon’s “eccentric appearance.”[32] His reputation was more than sartorial, however. Haddock observes that Lyon also had “a persuasive and flattering tongue, which at times served him in the absence of sincerity and ability.”[33] Moreover, Lyon was accused of chicanery and outright thievery. After being appointed by Lincoln to be the governor of the Idaho Territory, Lyon caused a scandal when he traveled around the territory displaying a piece of quartz that he claimed was a diamond that had been discovered in Idaho.[34] “But the pea-sized piece of quartz the governor was showing around looked real to the gullible. By the time wide-eyed prospectors found out they’d been conned, the governor had already skipped the state and was back in New York.”[35] Deciding it prudent to leave Idaho in the middle of the night under the pretext of going duck hunting, Lyon took with him more than $40,000 in government funds. When questioned about the funds, Lyon claimed that he had placed the money under his pillow on the return train trip to the East Coast and that the money had been stolen.[36] As the missing money story suggests, Lyon was “a gentleman of very lively imagination.”[37] That imagination apparently extended to some of the ceramics he had collected. For example, the final lot in Lyon’s 1876 auction was the “Elder Brewster Teapot” which, according to Lyon, had been brought to North America on the Mayflower in 1620.[38] Lyon was always vague about the provenance of this teapot, claiming to have purchased it from an anonymous woman in Vermont.[39] Newspaper reports about the auction noted that the purchaser of the teapot “was disagreeably surprised to find out afterwards that all the ‘first families’ in Boston had an ‘Elder Brewster Teapot,’ exactly like his own.”[40] The ceramics writer Alice Morse Earle dismissed Lyon’s claims as early as 1892, accurately suggesting that his teapot was at least a century younger than he alleged.[41] Klamkin similarly noted in 1972 that “many errors in attribution appear in the Lyon catalog.”[42] Lyon’s collection included much more than ceramics, and there were subsequent auctions of his collections, the most significant one taking place on January 25, 1882.[43] This auction included more plates associated with U.S. Presidents Adams, Taylor, Jackson, and Lincoln, as well as another “J” service plate.[44] As with the “Elder Brewster” teapot, subsequent buyers from the 1882 Lyon collection learned that the stated provenances were not always accurate. For example, the descendant of one of those purchasers recently donated to the Phillips Museum of Art at Franklin and Marshall College in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, two Chinese export jugs that purportedly had belonged to Benjamin Franklin but are decorated with a crest that bears little resemblance to the one Franklin actually used. Catalogers at the Phillips Museum clearly doubt that Franklin ever owned the jugs, noting, “If there is, indeed, a direct Franklin connection, it seems more likely due to purchase by a member of the Bache family [Richard Bache married Franklin’s daughter Sarah].” Of course many early collectors made claims that subsequent research has shown to be untrue, but these revelations do call Caleb Lyon’s credibility into question. Whether the product of wishful thinking or outright deception, the attribution of the “J” service plates sold in the 1876 and 1882 Lyon auctions cannot be considered reliable. It is essential to examine the part of the narrative involving acquisition of the “J” service by Jefferson’s Coolidge descendants, and the oft-repeated assertion that they bought the “J” service because they believed Jefferson had owned it. That assertion is not entirely true, and it may be entirely false. Thomas Jefferson Coolidge III, who loaned “J” service pieces to Monticello and the U.S. State Department, apparently did not believe that Jefferson had owned the service. Monticello’s curatorial notes contain the following information about Coolidge: “his father, who was in the shipping business purchased the large set many years ago. Based on information from his father, the set was made for Jefferson’s use while president; for reasons not known it failed to reach him in [Washington] or at Monticello and thus was never used by TJ or seen by him.”[45] It is true that the Coolidge family acquired the “J” service in the nineteenth century because of the Jefferson association, but apparently not because they believed Jefferson actually owned it. Thus the apocryphal story that Thomas Jefferson owned the “J” service can be traced not to the Coolidges, but to Caleb Lyon, an eccentric and voracious collector who had a reputation as a con man and a thief, and whose collection included many items that were not what he claimed them to be. The first lot in his 1876 auction was “an old Cup in blue and white, with figures and winter landscape.”[46] That description is probably accurate. The last lot in the auction was the “Elder Brewster” teapot, “brought over in the Mayflower.”[47] While the description of the object as a teapot is probably accurate, the Mayflower attribution is wildly implausible. A foundation of truth was embellished upon by wishful thinking or perhaps more Lyonesque chicanery. Similarly, the claim that the “J” service belonged to Jefferson is inaccurate but based on a foundation of truth.

To unpack the story, it is essential to set aside familiar assumptions, no matter how many times they have been repeated. The starting point in that regard is the cider jug in the collection of the Cincinnati Art Museum. The jug sold at auction at Park-Bernet in 1946 as property of Mary Adams Quincy (1845–1928), a direct descendant of President John Adams. As the auction catalog noted, the family believed that the jug had descended through the family from John Adams, having been given to him by Thomas Jefferson. If we set that family history aside and realize that the jug descended not in the Adams family but in the Quincy family, the evidence becomes more consistent and those pesky questions disappear. I have already mentioned several illustrious Boston families who are interconnected through trade and marriage. A brief explanation of the genealogy of one more Boston family is necessary at this point because the family connections are essential to understanding the complete provenance of the “J” service, as well as the “G” and “WMP” services. William Phillips Sr. (1722–1804) was a wealthy Boston merchant who had a hand in drafting the Massachusetts Constitution and in ratifying the U.S. Constitution. He married Abigail Bromfield in 1744. Of seven children born to them, four lived to adulthood: Abigail, William Jr., and twins Hannah and Sarah. Abigail Phillips married Josiah Quincy. The historian Edmund Quincy was their son. William Phillips Jr. married Miriam Mason. Hannah Phillips married Samuel Shaw. Hannah’s twin sister, Sarah Phillips, married Edward Dowse.[48] Thus, through these marriages, Josiah Quincy and William Phillips Jr. were brothers-in-law, as were Edward Dowse and Samuel Shaw. Samuel Shaw is well known as the supercargo (owner’s agent) on the Empress of China, the first American merchant vessel to travel to China, sailing from New York in February 1784 and returning in 1785. Similarly, Shaw’s brother-in-law Edward Dowse was also a China trader. Dowse accompanied Shaw on the trip to China, though Shaw died during the return voyage.[49] Edward Dowse appears in correspondence with Thomas Jefferson multiple times over several decades. Their earliest correspondence is relevant to the “J” service and is critical in understanding the provenance of the service.[50] Jefferson met Edward Dowse on the Isle of Wight in England in 1789 and asked Dowse to procure for him a set of table china from Canton.[51] Later that year, both men were safely home in the United States. Dowse, in Boston, wrote to Jefferson at Monticello: “I observe that your Excellency is appointed to the Secretaryship of home and foreign affairs, and, presuming, that in consequence thereof, you will not return to Paris as you intended, I shall take care to have your Service of China delivered to you, wherever you may reside in America.”[52] Jefferson received the letter and docketed it on January 1, 1790. Dowse presumably provided examples of available designs, as Jefferson wrote to him from New York on April 1, 1790. Jefferson asked Dowse to send the porcelain to him in New York: “Since my arrival here I have seen specimens of it and am much pleased with them, particularly those of dark or chocolate colored figures. I will beg the favor of you to make the set as full and numerous in every article as possible, particularly that of dishes, and of the smaller sizes of them.”[53] An American buyer ordering a porcelain dinner service from China in 1790 and expecting a quick delivery would have been disappointed. Under the best conditions, the voyage took more than a year. Edward Dowse’s next voyage to China took significantly longer. Indeed, more than three years passed before Dowse again wrote to Jefferson. Writing from Ostend, Belgium, on March 4, 1793, he stated, “Herewith will be deliver’d to you a Table Sett of China in Two Boxes, which I had made for you at Canton, agreeably to your Excellency’s desire, when I had the pleasure to see you at the Isle of Wight in the year [17]89.”[54] Dowse mentioned that he was sending the porcelain to Jefferson by way of Charleston, South Carolina, and referenced their discussions in 1789 rather than Jefferson’s letter to him in 1790. Dowse also recognized that in the years between the order and the delivery, Jefferson might have given up hope of receiving the porcelain from China and might have ordered porcelain from another source, writing, “It is so long ago that possibly you may have supplied yourself already.”[55] Dowse also suggested that if he remembered Jefferson’s mention of the “dark or chocolate colored figures” correctly, the porcelain being delivered did not match that description and, therefore, “the China may not be executed to your liking.”[56] Dowse shrewdly gave Jefferson the option to decline the service: “In either case, I beg you would not think it necessary to retain it; but send it back to me at Boston, where I expect to be about two months from this; and I shall not draw upon you for the amount, until you inform me that the China is entirely to your liking.”[57] On July 26, 1793, Jefferson replied to Dowse from Philadelphia, acknowledging receipt of the two boxes of china by way of Charleston.[58] Jefferson noted that he had become “double-stocked” with china, and no longer needed the china Dowse had procured for him. Jefferson accepted Dowse’s offer to reject the china, placing Dowse “at your ease in doing what shall be to your best advantage.”[59] Significantly, Jefferson stated that “the boxes are here, unopened, and shall be delivered in that state to your order.”[60] Jefferson meticulously recorded in his account book paying for “portage of 2 boxes of china from Mr. Dowse.”[61] Jefferson also wrote to Dowse’s agents in Charleston on August 26, 1793, noting that four years had passed between the order and the delivery, and that he “had abandoned the expectation of this and supplied myself fully.”[62] He continued: “You will therefore be so good as to consider this parcel as still making part of his cargo, and subject here to his order, which I expected to receive, as according to his letter he should have been at Boston by this time.”[63] On August 29, 1793, Dowse wrote to Jefferson from Boston that he had received Jefferson’s letter declining the china. Dowse clearly was not surprised, and he reassured Jefferson that “your returning it, will not be of the least disadvantage to me; on the contrary, a benefit.”[64] Thus, Edward Dowse retained the Chinese export service he had ordered for Jefferson, with the understanding that he was free to sell the service and recoup his money or, as Dowse hinted, perhaps make a profit. The challenge now becomes proving that the service Jefferson and Dowse corresponded about was in fact the “J” service, and if it was, what happened to it after Jefferson declined to purchase it. We must connect the dots between Edward Dowse, who owned this Chinese export service in 1790, and Mary Adams Quincy, who ended up owning a cider jug from the “J” service in the 1940s. Fortunately, the dots are close and easily connected. As suggested earlier, the evidence shows that the jug descended through the Quincy family, as did two other pieces from the service. We jump to Mary Adams Quincy’s ownership of the jug and work backward. Mary Adams Quincy’s husband was Dr. Henry Parker Quincy (1838–1899). His father was Edmund Quincy, who in 1868 published a biography of his own father, Josiah Quincy (1772–1864). In the biography, Edmund Quincy wrote: I have in my possession a mighty punch-bowl bearing Mr. Jefferson’s cypher and his famous motto, “rebellion to tyrants is obedience to god,” which was part of a dinner-set which Mr. Dowse had had made for him, at his request, in Canton, when he was Secretary of State. Mr. Dowse having been unduly delayed in China, Mr. Jefferson had been obliged to provide himself with another service. Mr. Dowse refused to allow his friend to take the superfluous set off his hands, which he was entirely willing to do, and found a purchaser for it in a gentleman of Boston, whom the cipher suited, and who did not object to the motto. The punch-bowl and a pair of pitchers he retained in rei memoriam.[65] Edmund Quincy’s description of the two jugs and the punch bowl is unmistakable. The “J” service jug in the collection of the Cincinnati Art Museum is certainly one of the two jugs he describes. By 1946 one of the jugs had lost its lid and descended, along with the punch bowl, to the family of Mary Adams Quincy.[66] The Phillips family connections described above make the descent clear. Edward Dowse and his wife, Sarah Phillips Dowse, had no children. Edward died in 1828. When Sarah died in 1839, their property descended to her nephew Josiah Quincy, and thence through the Quincy family to Mary Adams Quincy.[67] The chain of custody of the remainder of the “J” service after Jefferson forwarded it to Dowse in Boston is less clear, but there are some compelling clues. Edmund Quincy mentioned that Dowse sold the service—minus those pieces he retained—to a gentleman in Boston. That gentleman, according to Quincy, did not object to the monogram.[68] Newspaper accounts suggest that Coolidge purchased the service from a man named Jones, which is consistent with Quincy’s statement.[69] While there were several prominent men named Jones in Boston in the late 1790s, a likely buyer might have been John Coffin Jones, who was an admirer of Thomas Jefferson.[70] John Coffin Jones had a son, John Coffin Jones Jr., first American consular agent to Hawai‘i. Jones Jr. returned to Massachusetts and died in 1861. His will was probated in 1862, with his estate held by a trustee to pay income to his widow during her life. His widow died in 1900.[71] It was during this period that Coolidge purchased the “J” service. More research may uncover documentation of Coolidge’s purchase of the “J” service pieces from the Jones estate. When Thomas Jefferson Coolidge acquired the “J” service pieces in the late 1800s, he likely knew that the service was merely ordered for Jefferson. As the generations passed, the distinction between china purchased “for” Jefferson, and china purchased and used “by” Jefferson, became blurred. The Caleb Lyon attribution and imprecise news reporting likely were contributing factors. This explanation resolves the pesky questions mentioned earlier. If Jefferson did not own the “J” service, we would not expect to find archaeological evidence of it at Monticello. The fact that he sent it on to Boston, where Dowse later sold most of it, explains why most of the service later turned up in Boston, to be scooped up by Thomas Jefferson Coolidge in the late nineteenth century. The Jefferson association was attractive to him, even if the association was not one of ownership. Ellen Randolph Coolidge never mentioned the “J” service in her writings because she never saw it. Similarly, Jefferson and Adams never mentioned the cider jug in their correspondence because neither man ever owned it. The conundrum of Christopher Gore or his wife ordering an expensive and expansive customized set of porcelain for a political enemy is also resolved. Dowse almost certainly ordered the “G” service for the Gores at the same time he ordered the “J” service for Jefferson. The delivery date of 1793 is consistent with the understanding of the Gore Place Society, which as of the writing of this article did not have any specific records documenting Christopher Gore’s purchase of the “G” service.[72] Edward Dowse’s purchase of the “J” service and the “G” service leads wonderfully to an attribution of ownership of the “WMP” service, which heretofore has had no suggested owner. The shield-and-armor design was not a stock pattern. It appears only on these three known services, and Dowse might well have designed it himself. What remains is to track down Dowse’s customer with those initials, and fortunately we need look no further than his own family. Dowse’s brother-in-law William Phillips Jr. married Miriam Mason in 1794. As a couple’s monogram typically would be written with the initial of the husband’s given name first, followed by the initial of the wife’s given name, followed by the initial of their shared last name, it is easily conceivable that the service was made for William and Miriam Phillips.

The goal of this article is to prove a negative—namely, that Thomas Jefferson did not own or use the “J” service at Monticello, in the White House, or anywhere else. The correspondence between Jefferson and Edward Dowse documents the fact that Dowse procured a service from Canton on behalf of Jefferson. In the years that passed between order and delivery, Jefferson’s circumstances changed and he no longer needed the service Dowse procured. Dowse’s nephew Edmund Quincy illustrates the fact that the service his uncle had ordered for Jefferson, and that was the subject of the correspondence, was in fact the “J” service. Thus, while the service was ordered for Jefferson, we have it in his own handwriting that he sent it back to Dowse unopened. Jefferson did not own it. He did not use it. If we take Jefferson at his word, he did not even see it. The 1794 Château Lafite in the bottle with the carved initials “Th. J.” was a deliberate fake. In contrast, the myth that Thomas Jefferson owned or used the “J” service is not deliberate fakery, but instead wishful thinking based on a grain of truth. The commonality is Jefferson himself. Owning an object that a great historical figure owned provides a tangible connection with that person. Caleb Lyon was one of the first ceramics collectors who appreciated that connection. Raleigh DeGeer Amyx, in the tradition of Caleb Lyon, no doubt wanted to believe that Thomas Jefferson owned the “J” service, and he made a determined effort to muster facts to support that belief and to provide a tangible connection to Jefferson. Edmund Quincy wrote that Dowse retained three pieces of the service he had ordered for Thomas Jefferson in rei memoriam, as a reminder. The tale of the “J” service reminds us of the history of ceramics collecting in the United States, as the nineteenth century bric-à-bracqueurs paved the way for today’s ceramics scholars and enthusiasts. The story connects us with such legendary Americans as Thomas Jefferson and John Adams, and lesser-known but nevertheless important figures such as Ellen Coolidge and Edward Dowse. Colorful characters such as Caleb Lyon and Raleigh DeGeer Amyx make the story even more engaging. In this way, the story of the “J” service serves as a reminder of the important role that ceramics and ceramics collectors play in our collective history as a nation.

1. Ellen Wayles Randolph Coolidge to Joseph Coolidge, October 24, 1858, in Ellen Wayles Coolidge Letterbook, Ellen Wayles Coolidge Correspondence, University of Virginia Library Special Collections. See also William G. Hyland Jr., In Defense of Thomas Jefferson: The Sally Hem- ings Sex Scandal (New York: Thomas Dunne Books, 2009), p. 201, in which the letter is reprinted. 2. Ellen Wayles Randolph Coolidge to Joseph Coolidge, October 24, 1858, in Ellen Wayles Coolidge Letterbook, Ellen Wayles Coolidge Correspondence, University of Virginia Library Special Collections. See also Hyland, In Defense of Thomas Jefferson, p. 201, in which the letter is reprinted. 3. Lyon was briefly the Territorial Governor of Idaho. 4. Henry D. Miner, Governor Caleb Lyon Collection of Oriental and Occidental Ceramics, sale cat., April 24, 1876 ([New York]: Henry D. Miner, 1876). 5. Ibid., p. 67. 6. Ibid., p. 71. 7. Boston Post, April 15, 1876, p. 3. 8. Times (Philadelphia), April 25, 1876, p. 2. 9. James Grant Wilson, “About Bric-a-Brac,” Art Journal, n.s., 4 (1878): 313–15, 314. 10. Ibid. 11. Alice Morse Earle, China Collecting in America (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1892); Ada Walker Camehl, The Blue-China Book: Early American Scenes and History Pictured in the Pottery of the Time . . . (New York: E. P. Dutton, 1916); Jean McClure Mudge, Chinese Export Porcelain for the American Trade, 1785–1835 (Newark: University of Delaware Press, 1962); Marian Klamkin, White House China (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1972). 12. David Sanctuary Howard, Chinese Armorial Porcelain, Volume II (Chippenham, U.K.: Heirloom and Howard, 2003), p. 595. 13. Evidence of this link, according to the catalogs, included the service being published in both editions of Klapthor’s books on White House china, as well as the service having been displayed at the White House, the U.S. State Department, and Monticello. Christie’s, English Pottery and Chinese Export Art, sale cat. (New York: Christie’s, 2013), lots 448–458; Chinese Export Art, sale cat. (New York: Christie’s, 2014), lots 437–446; Mandarin & Menagerie: The Sowell Collection and Chinese Export Art from Various Owners, sale cat. (New York: Christie’s, 2015), lots 167–176. 14. Mentioned in, for example, the Christie’s auction catalogs cited in note 13 above. 15. In “Gives Jefferson China,” New York Times, October 21, 1906, p. 1, his first initial was misstated. In an article on the same gift, the New York Sun referred to him simply as Jefferson Coolidge; “Jefferson’s China Dinner Set,” New York Sun, October 21, 1906, p. 9. The Times-Democrat (New Orleans), in “Some of Jefferson’s China,” October 23, 1906, p. 7, referred to him as Thomas J. Coolidge. 16. The same information is contained in all three of the Christie’s auction catalogs cited in note 13 above. 17. Parke-Bernet Galleries, Adams-Quincy Heirlooms from the Heritage of Mary Adams Quincy [1846–1929], Granddaughter of President John Quincy Adams, sale cat. (New York: Parke-Bernet Galleries, 1946), lots 64 and 65. The Cincinnati Art Museum’s jug was part of an exhibition at the Taft Museum in Cincinnati in 1998. The exhibition catalog cautiously noted: “Jefferson purportedly presented this jug to President John Adams according to Adams’ descendants who formerly owned it.” Ellen Avril, East Meets West: Chinese Export Art and Design (Cincinnati, Ohio: Taft Museum, 1998), p. 11. 18. The same information is contained in all three of the Christie’s auction catalogs cited in note 13 above. 19. On January 30, 2014, Nate D. Sanders Auctions sold a “very scarce and beautiful china plate from the administration of Thomas Jefferson” (lot 91). The sale catalog description suggests that Jefferson used the “J” service in Washington rather than at Monticello. On February 5, 2015, Morphy Auctions (now James D. Julia Auctions) sold a “Rare Canton footed open salt from the Thomas Jefferson ‘J’ Dinner Service” (lot 2161), noting that “through scholarly research and documentation a direct link to Jefferson has not been established nor have shards of this service been excavated at Monticello[;] it is widely accepted that this service was Jefferson’s and research continues to grow as other pieces are found.[”] The sale catalog references Mudge, who in turn had relied on the White House description, which in turn had relied on information provided by the donor, Thomas Jefferson Coolidge. Also in February 2015, RR Auction sold an “Original Thomas Jefferson presidential china soup bowl” (lot 2002). The catalog enthusiastically tantalized the buyer with “An incredibly rare opportunity to acquire such an attractive piece of US history, as most, if not all, of the other china from the first three presidents were destroyed when the British ransacked and burned the Executive Mansion during the War of 1812.” The RR Auction catalog thus recounts a well-established historical fact—the burning of the Executive Mansion during the war—and then connects that fact with the presumption that the “J” service was actually in the Executive Mansion at the time the British burned it. “The historical significance of such a rare piece of presidential porcelain from a well-known collection, in such truly superb condition, is not to be understated,” the catalog pronounces. See also RR Auction, February 2020, lot 4003, for another example from the “J” service, described as “Extraordinarily rare circa 1790s china serving plate from Thomas Jefferson’s White House service.” (The stated provenance for the lot is the Raleigh DeGeer Amyx Collection.) Thomaston Place Auction Galleries advertised the sale of a “Rare Jefferson China Cup—Lowestoft Porcelain Custard Cup from the service of Thomas Jefferson” (August 29, 2015, lot 1). The catalog description repeated the speculation that Christopher Gore had ordered the service for Jefferson. Pieces of the “J” service have also been offered for sale in the retail environment, including at the 2019 Delaware Antiques Show. A review of the show published in Maine Antique Digest embellished some of the details about the service. The caption for a photo of “J” service pots de crème, for example, noted that “the service was acquired by a descendant of Jefferson at the bankruptcy sale after his death.” The caption suggests that the “J” service was actually in the 1827 sale of Jefferson’s belongings and that a Jefferson descendant had purchased it. No other publication has proposed this specific provenance. Lita Solis-Cohen, “The 2019 Delaware Show,” Maine Antique Digest 47, no. 1 (January 2020): 108. 20. Raleigh DeGeer Amyx, “Thomas Jefferson circa 1790’s China Acquired by The Raleigh DeGeer Amyx Collection,” June 11, 2013, https://www.prweb.com/releases/thomas-jefferson/presidential-china/prweb10796585.htm. 21. Ibid. 22. Ibid. 23. Amyx, The Raleigh DeGeer Amyx Collection: White House China, 20th & 21st Century, e-book available online at http://blog.americanheritage1.com/free-e-book-elegant-white-house-china-of-the-20th-21st-century. 24. Ibid. 25. Benjamin Wallace, The Billionaire’s Vinegar: The Mystery of the World’s Most Expensive Bottle of Wine (New York: Three Rivers Press, 2009), p. 281. 26. Pieces of the “WMP” service were sold at Christie’s on January 23, 1993, sale 7604, lot 404, and at Freeman’s on May 2, 2014, sale 1489, lot 60, without mention of an original owner. 27. Accession records at Gore Place relating to pieces of Gore’s “G” service state: “Stylistically, such a set could date from about 1790–1800. However, since the Gores were abroad from 1796–1804 and acquired a Paris porcelain dinner service in Europe, this service probably dates from between 1790 and 1796.” 28. Susan R. Stein, The Worlds of Thomas Jefferson at Monticello (New York: Harry N. Abrams, in association with the Thomas Jefferson Memorial Foundation, 1993), p. 348. See also Margaret Brown Klapthor, Official White House China: 1789 to the Present (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1975), and Margaret Brown Klapthor, Official White House China: 1789 to the Present, 2nd ed. (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1999). 29. In 1864 Lincoln perhaps began to recognize that the Lyon appointment was ill-advised. In response to a now-lost letter from Roscoe Conkling criticizing Lyon, Lincoln wrote that “his nomination to some respectable office was repeatedly urged upon me certainly by two, if not three Senators of the highest standing; and your letter contains the first imputation I ever heard against his moral character.” Abraham Lincoln to Roscoe Conkling, February 19, 1864, Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress: Series 1, General Correspondence, 1833 to 1916 (19,114). 30. John Haddock, The Growth of a Century: As Illustrated in the History of Jefferson County, New York, from 1793 to 1894 (Philadelphia: Sherman & Co., 1894). 31. Charleston Daily Courier, August 24, 1853, p. 2. 32. New York Daily Herald, March 23, 1853, p. 7. 33. Haddock, Growth of a Century, p. 22. 34. Syd Albright. “Idaho Corruption in High Places,” Coeur D’Alene/Post Falls Press (Coeur D’Alene, Idaho), May 26, 2013. 35. Ibid. 36. Lyon’s obituary in the New York Times, September 9, 1875, p. 4, mentions the train robbery without further comment, though other papers reported Lyon’s claim with great skepticism. See, e.g., “The Robbery of Caleb Lyon,” Rutland Daily Herald (Rutland, Vt.), December 19, 1866, p. 2. 37. Rutland Daily Herald, December 19, 1866, p. 2. 38. Miner, Governor Caleb Lyon Collection of Oriental and Occidental Ceramics, p. 67. 39. Earle, China Collecting in America, p. 203. 40. Mobile Daily Tribune (Mobile, Ala.), July 29, 1876, p. 1. 41. Earle, China Collecting in America, p. 203. 42. Klamkin, White House China, p. 27. 43. George A. Leavitt & Co., The Governor Caleb Lyon Collection of Porcelains, Objects of Art, Washingtoniana, Oil Paintings, &c. (New York: George A. Leavitt & Co., 1882). Leavitt also conducted a sale of Lyon’s library on March 22, 1882; advertisement, New York Times, March 19, 1882, p. 9. 44. The Governor Caleb Lyon Collection of Porcelains, Objects of Art, Washingtoniana, Oil Paintings, &c., lot 107. See also “Art Objects at Auction: Sale of the Caleb Lyon Collection of Porcelains, Bric-à-Brac, and Paintings,” New York Times, January 26, 1882, reporting a sale price for the “J” service plate of $6.00. 45. Monticello database for acc. no. 1957-34-2a. According to Monticello, that piece was returned to the lender. See also Object Report for Cider Jug (1955.758) dated December 4, 2003, curatorial file, Cincinnati Art Museum. 46. Miner, Governor Caleb Lyon Collection of Oriental and Occidental Ceramics, p. 5. 47. Ibid., p. 72. 48. Hamilton Andrews Hill, “William Phillips and William Phillips, Father and Son, 1722–1827,” New England Historical and Genealogical Register 39 (April 1885): 111–17; Henry Bond, Genealogies of the Families and Descendants of the Early Settlers of Watertown, Massachusetts, including Waltham and Weston, 2nd ed., 2 vols. in 1 (Boston, Mass.: New England Historic Genealogical Society, 1860), pp. 872–82; Azro Milton Dows, comp., The Dows or Dowse Family in America: A Genealogy of the Descendants of Lawrence Dows (Lowell, Mass.: Vox Populi Press, 1890). 49. Josiah Quincy, The Journals of Major Samuel Shaw, the First American Consul at Canton: With a Life of the Author (Boston, Mass.: Wm. Crosby and H. P. Nichols, 1847), p. 125. 50. Later correspondence between Jefferson and Dowse is often cited by scholars investigating Jefferson’s religious beliefs. 51. James A. Bear Jr. and Lucia C. Stanton, eds., Jefferson’s Memorandum Books: Accounts, with Legal Records and Miscellany, 1767–1826, 2 vols. (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1997), 2:899. 52. Thomas Jefferson from Edward Dowse, November 29, 1789, in Julian P. Boyd, ed., The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, Vol. 15, 27 March 1789 to 30 November 1789 (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1958), p. 563. 53. Thomas Jefferson to Edward Dowse, April 1, 1790, in Julian P. Boyd, ed., The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, Vol. 16, 30 November 1789 to 4 July 1790 (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1961), pp. 286–87. 54. Thomas Jefferson from Edward Dowse, March 4, 1793, in Julian P. Boyd, ed., The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, Vol. 25, 1 January to 10 May 1793 (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1992), p. 315. 55. Ibid. 56. Ibid. 57. Ibid. 58. From Thomas Jefferson to Edward Dowse, July 26, 1793, in John Catanzariti, ed., The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, Vol. 26, 11 May to 31 August 1793 (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1995), pp. 570–71. 59. Ibid. 60. Ibid. 61. Bear and Stanton, Jefferson’s Memorandum Books, 2:899n33. 62. From Thomas Jefferson to Thayer, Bartlett & Company, August 26, 1793, in Catanzariti, Papers of Thomas Jefferson, Vol. 26, p. 762. 63. Ibid. 64. Thomas Jefferson from Edward Dowse, August 29, 1793, in Catanzariti, Papers of Thomas Jefferson, Vol. 26, p. 783. 65. Edmund Quincy, Life of Josiah Quincy of Massachusetts (Boston, Mass.: Ticknor and Fields, 1868), p. 386. 66. The whereabouts of the punch bowl and the other jug are not known to the author. The lid currently on the jug in Cincinnati is an appropriate replacement, though not a perfect fit. The replacement lid was likely supplied by the dealer/collector Neil Gest, who purchased the jug at the auction in 1946 and donated it to the museum in 1955. 67. “Mrs. Mary Adams Quincy,” Boston Globe, August 22, 1928, p. 27; “Dr. H. P. Quincy Buried,” Boston Globe, March 14, 1899, p. 7; “Marriages,” Boston Globe, June 22, 1877, p. 6; “Quincy Family Papers, 1639–1930,” Massachusetts Historical Society, https://www.masshist .org/collection-guides/view/fa0291. 68. Edmund Quincy also recorded that the buyer did not object to the motto. This suggests that he had not seen any of the pieces that did not descend in his family, since none of those other pieces appears to have had the motto added. The banderole and motto appear on only the three largest (and probably most expensive) pieces of the “J” service. Adding the banderole and motto to the entire service would have resulted in a substantially higher cost. 69. “Jefferson’s China Dinner Set,” New York Sun, October 21, 1906, p. 9. 70. When Jefferson was Minister to France, John Coffin Jones was traveling in France, carrying a letter of introduction to Jefferson from Henry Knox. Jones later acknowledged Jefferson’s assistance in a congratulatory letter to Jefferson dated May 1, 1790. Boyd, Papers of Thomas Jefferson, Vol. 16, pp. 397–400. 71. Charles C. Jones v. Carlos S. Jones et al., 233 Mass. 540 (March 7–April 11, 1916). 72. The Gore association for the “G” service is established by archaeological evidence and other documentary records.

Ellen Wayles Randolph Coolidge to Joseph Coolidge, October 24, 1858, in Ellen Wayles Coolidge Letterbook, Ellen Wayles Coolidge Correspondence, University of Virginia Library Special Collections. See also William G. Hyland Jr., In Defense of Thomas Jefferson: The Sally Hemings Sex Scandal (New York: Thomas Dunne Books, 2009), p. 201, in which the letter is reprinted.

Ellen Wayles Randolph Coolidge to Joseph Coolidge, October 24, 1858, in Ellen Wayles Coolidge Letterbook, Ellen Wayles Coolidge Correspondence, University of Virginia Library Special Collections. See also Hyland, In Defense of Thomas Jefferson, p. 201, in which the letter is reprinted.

Lyon was briefly the Territorial Governor of Idaho.

Henry D. Miner, Governor Caleb Lyon Collection of Oriental and Occidental Ceramics, sale cat., April 24, 1876 ([New York]: Henry D. Miner, 1876).

Ibid., p. 67.

Ibid., p. 71.

Boston Post, April 15, 1876, p. 3.

Times (Philadelphia), April 25, 1876, p. 2.

James Grant Wilson, “About Bric-a-Brac,” Art Journal, n.s., 4 (1878): 313–15, 314.

Ibid.

Alice Morse Earle, China Collecting in America (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1892); Ada Walker Camehl, The Blue-China Book: Early American Scenes and History Pictured in the Pottery of the Time . . . (New York: E. P. Dutton, 1916); Jean McClure Mudge, Chinese Export Porcelain for the American Trade, 1785–1835 (Newark: University of Delaware Press, 1962); Marian Klamkin, White House China (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1972).

David Sanctuary Howard, Chinese Armorial Porcelain, Volume II (Chippenham, U.K.: Heirloom and Howard, 2003), p. 595.

Evidence of this link, according to the catalogs, included the service being published in both editions of Klapthor’s books on White House china, as well as the service having been displayed at the White House, the U.S. State Department, and Monticello. Christie’s, English Pottery and Chinese Export Art, sale cat. (New York: Christie’s, 2013), lots 448–458; Chinese Export Art, sale cat. (New York: Christie’s, 2014), lots 437–446; Mandarin & Menagerie: The Sowell Collection and Chinese Export Art from Various Owners, sale cat. (New York: Christie’s, 2015), lots 167–176.

Mentioned in, for example, the Christie’s auction catalogs cited in note 13 above.

In “Gives Jefferson China,” New York Times, October 21, 1906, p. 1, his first initial was misstated. In an article on the same gift, the New York Sun referred to him simply as Jefferson Coolidge; “Jefferson’s China Dinner Set,” New York Sun, October 21, 1906, p. 9. The Times-Democrat (New Orleans), in “Some of Jefferson’s China,” October 23, 1906, p. 7, referred to him as Thomas J. Coolidge.

The same information is contained in all three of the Christie’s auction catalogs cited in note 13 above.

Parke-Bernet Galleries, Adams-Quincy Heirlooms from the Heritage of Mary Adams Quincy [1846–1929], Granddaughter of President John Quincy Adams, sale cat. (New York: Parke-Bernet Galleries, 1946), lots 64 and 65. The Cincinnati Art Museum’s jug was part of an exhibition at the Taft Museum in Cincinnati in 1998. The exhibition catalog cautiously noted: “Jefferson purportedly presented this jug to President John Adams according to Adams’ descendants who formerly owned it.” Ellen Avril, East Meets West: Chinese Export Art and Design (Cincinnati, Ohio: Taft Museum, 1998), p. 11.

The same information is contained in all three of the Christie’s auction catalogs cited in note 13 above.

On January 30, 2014, Nate D. Sanders Auctions sold a “very scarce and beautiful china plate from the administration of Thomas Jefferson” (lot 91). The sale catalog description suggests that Jefferson used the “J” service in Washington rather than at Monticello. On February 5, 2015, Morphy Auctions (now James D. Julia Auctions) sold a “Rare Canton footed open salt from the Thomas Jefferson ‘J’ Dinner Service” (lot 2161), noting that “through scholarly research and documentation a direct link to Jefferson has not been established nor have shards of this service been excavated at Monticello[;] it is widely accepted that this service was Jefferson’s and research continues to grow as other pieces are found.” The sale catalog references Mudge, who in turn had relied on the White House description, which in turn had relied on information provided by the donor, Thomas Jefferson Coolidge.

Also in February 2015, RR Auction sold an “Original Thomas Jefferson presidential china soup bowl” (lot 2002). The catalog enthusiastically tantalized the buyer with “An incredibly rare opportunity to acquire such an attractive piece of US history, as most, if not all, of the other china from the first three presidents were destroyed when the British ransacked and burned the Executive Mansion during the War of 1812.” The RR Auction catalog thus recounts a well-established historical fact—the burning of the Executive Mansion during the war—and then connects that fact with the presumption that the “J” service was actually in the Executive Mansion at the time the British burned it. “The historical significance of such a rare piece of presidential porcelain from a well-known collection, in such truly superb condition, is not to be understated,” the catalog pronounces. See also RR Auction, February 2020, lot 4003, for another example from the “J” service, described as “Extraordinarily rare circa 1790s china serving plate from Thomas Jefferson’s White House service.” (The stated provenance for the lot is the Raleigh DeGeer Amyx Collection.) Thomaston Place Auction Galleries advertised the sale of a “Rare Jefferson China Cup—Lowestoft Porcelain Custard Cup from the service of Thomas Jefferson” (August 29, 2015, lot 1). The catalog description repeated the speculation that Christopher Gore had ordered the service for Jefferson. Pieces of the “J” service have also been offered for sale in the retail environment, including at the 2019 Delaware Antiques Show. A review of the show published in Maine Antique Digest embellished some of the details about the service. The caption for a photo of “J” service pots de crème, for example, noted that “the service was acquired by a descendant of Jefferson at the bankruptcy sale after his death.” The caption suggests that the “J” service was actually in the 1827 sale of Jefferson’s belongings and that a Jefferson descendant had purchased it. No other publication has proposed this specific provenance. Lita Solis-Cohen, “The 2019 Delaware Show,” Maine Antique Digest 47, no. 1 (January 2020): 108.

Raleigh DeGeer Amyx, “Thomas Jefferson circa 1790’s China Acquired by The Raleigh DeGeer Amyx Collection,” June 11, 2013, https://www.prweb.com/releases/thomas-Jefferson/presidential-china/prweb10796585.htm.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Amyx, The Raleigh DeGeer Amyx Collection: White House China, 20th & 21st Century, e-book available online at http://blog.americanheritage1.com/free-e-book-elegant-white-house-china-of-the-20th-21st-century.

Ibid.

Benjamin Wallace, The Billionaire’s Vinegar: The Mystery of the World’s Most Expensive Bottle of Wine (New York: Three Rivers Press, 2009), p. 281.

Pieces of the “WMP” service were sold at Christie’s on January 23, 1993, sale 7604, lot 404, and at Freeman’s on May 2, 2014, sale 1489, lot 60, without mention of an original owner.

Accession records at Gore Place relating to pieces of Gore’s “G” service state: “Stylistically, such a set could date from about 1790–1800. However, since the Gores were abroad from 1796–1804 and acquired a Paris porcelain dinner service in Europe, this service probably dates from between 1790 and 1796.”

Susan R. Stein, The Worlds of Thomas Jefferson at Monticello (New York: Harry N. Abrams, in association with the Thomas Jefferson Memorial Foundation, 1993), p. 348. See also Margaret Brown Klapthor, Official White House China: 1789 to the Present (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1975), and Margaret Brown Klapthor, Official White House China: 1789 to the Present, 2nd ed. (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1999).

In 1864 Lincoln perhaps began to recognize that the Lyon appointment was ill-advised. In response to a now-lost letter from Roscoe Conkling criticizing Lyon, Lincoln wrote that “his nomination to some respectable office was repeatedly urged upon me certainly by two, if not three Senators of the highest standing; and your letter contains the first imputation I ever heard against his moral character.” Abraham Lincoln to Roscoe Conkling, February 19, 1864, Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress: Series 1, General Correspondence, 1833 to 1916 (19,114).

John Haddock, The Growth of a Century: As Illustrated in the History of Jefferson County, New York, from 1793 to 1894 (Philadelphia: Sherman & Co., 1894).

Charleston Daily Courier, August 24, 1853, p. 2

New York Daily Herald, March 23, 1853, p. 7.

Haddock, Growth of a Century, p. 22.

Syd Albright. “Idaho Corruption in High Places,” Coeur D’Alene/Post Falls Press (Coeur D’Alene, Idaho), May 26, 2013.

Ibid.

Lyon’s obituary in the New York Times, September 9, 1875, p. 4, mentions the train robbery without further comment, though other papers reported Lyon’s claim with great skepticism. See, e.g., “The Robbery of Caleb Lyon,” Rutland Daily Herald (Rutland, Vt.), December 19, 1866, p. 2.

Rutland Daily Herald, December 19, 1866, p. 2.

Miner, Governor Caleb Lyon Collection of Oriental and Occidental Ceramics, p. 67.

Earle, China Collecting in America, p. 203.

Mobile Daily Tribune (Mobile, Ala.), July 29, 1876, p. 1.

Earle, China Collecting in America, p. 203.

Klamkin, White House China, p. 27.

George A. Leavitt & Co., The Governor Caleb Lyon Collection of Porcelains, Objects of Art, Washingtoniana, Oil Paintings, &c. (New York: George A. Leavitt & Co., 1882). Leavitt also conducted a sale of Lyon’s library on March 22, 1882; advertisement, New York Times, March 19, 1882, p. 9.

The Governor Caleb Lyon Collection of Porcelains, Objects of Art, Washingtoniana, Oil Paintings, &c., lot 107. See also “Art Objects at Auction: Sale of the Caleb Lyon Collection of Porcelains, Bric-à-Brac, and Paintings,” New York Times, January 26, 1882, reporting a sale price for the “J” service plate of $6.00.

Monticello database for acc. no. 1957-34-2a. According to Monticello, that piece was returned to the lender. See also Object Report for Cider Jug (1955.758) dated December 4, 2003, curatorial file, Cincinnati Art Museum.

Miner, Governor Caleb Lyon Collection of Oriental and Occidental Ceramics, p. 5.

Ibid., p. 72.

Hamilton Andrews Hill, “William Phillips and William Phillips, Father and Son, 1722–1827,” New England Historical and Genealogical Register 39 (April 1885): 111–17; Henry Bond, Genealogies of the Families and Descendants of the Early Settlers of Watertown, Massachusetts, including Waltham and Weston, 2nd ed., 2 vols. in 1 (Boston, Mass.: New England Historic Genealogical Society, 1860), pp. 872–82; Azro Milton Dows, comp., The Dows or Dowse Family in America: A Genealogy of the Descendants of Lawrence Dows (Lowell, Mass.: Vox Populi Press, 1890).

Josiah Quincy, The Journals of Major Samuel Shaw, the First American Consul at Canton: With a Life of the Author (Boston, Mass.: Wm. Crosby and H. P. Nichols, 1847), p. 125.

Later correspondence between Jefferson and Dowse is often cited by scholars investigating Jefferson’s religious beliefs.

James A. Bear Jr. and Lucia C. Stanton, eds., Jefferson’s Memorandum Books: Accounts, with Legal Records and Miscellany, 1767–1826, 2 vols. (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1997), 2:899.

Thomas Jefferson from Edward Dowse, November 29, 1789, in Julian P. Boyd, ed., The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, Vol. 15, 27 March 1789 to 30 November 1789 (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1958), p. 563.

Thomas Jefferson to Edward Dowse, April 1, 1790, in Julian P. Boyd, ed., The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, Vol. 16, 30 November 1789 to 4 July 1790 (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1961), pp. 286–87.

Thomas Jefferson from Edward Dowse, March 4, 1793, in Julian P. Boyd, ed., The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, Vol. 25, 1 January to 10 May 1793 (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1992), p. 315.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

From Thomas Jefferson to Edward Dowse, July 26, 1793, in John Catanzariti, ed., The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, Vol. 26, 11 May to 31 August 1793 (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1995), pp. 570–71.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Bear and Stanton, Jefferson’s Memorandum Books, 2:899n33.

From Thomas Jefferson to Thayer, Bartlett & Company, August 26, 1793, in Catanzariti, Papers of Thomas Jefferson, Vol. 26, p. 762.

Ibid.

Thomas Jefferson from Edward Dowse, August 29, 1793, in Catanzariti, Papers of Thomas Jefferson, Vol. 26, p. 783.

Edmund Quincy, Life of Josiah Quincy of Massachusetts (Boston, Mass.: Ticknor and Fields, 1868), p. 386.

The whereabouts of the punch bowl and the other jug are not known to the author. The lid currently on the jug in Cincinnati is an appropriate replacement, though not a perfect fit. The replacement lid was likely supplied by the dealer/collector Neil Gest, who purchased the jug at the auction in 1946 and donated it to the museum in 1955.

“Mrs. Mary Adams Quincy,” Boston Globe, August 22, 1928, p. 27; “Dr. H. P. Quincy Buried,” Boston Globe, March 14, 1899, p. 7; “Marriages,” Boston Globe, June 22, 1877, p. 6; “Quincy Family Papers, 1639–1930,” Massachusetts Historical Society, https://www.masshist.org/collection-guides/view/fa0291.

Edmund Quincy also recorded that the buyer did not object to the motto. This suggests that he had not seen any of the pieces that did not descend in his family, since none of those other pieces appears to have had the motto added. The banderole and motto appear on only the three largest (and probably most expensive) pieces of the “J” service. Adding the banderole and motto to the entire service would have resulted in a substantially higher cost.

“Jefferson’s China Dinner Set,” New York Sun, October 21, 1906, p. 9.

When Jefferson was Minister to France, John Coffin Jones was traveling in France, carrying a letter of introduction to Jefferson from Henry Knox. Jones later acknowledged Jefferson’s assistance in a congratulatory letter to Jefferson dated May 1, 1790. Boyd, Papers of Thomas Jefferson, Vol. 16, pp. 397–400.

Charles C. Jones v. Carlos S. Jones et al., 233 Mass. 540 (March 7–April 11, 1916).

The Gore association for the “G” service is established by archaeological evidence and other documentary records.