Reconstructed ca. 1740 kitchen, Kelton House, Warwick, Massachusetts, twentieth century. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The house was moved to Wisconsin in the third quarter of the twentieth century.

Dresser, southeastern Pennsylvania, ca. 1750. Walnut and mixed woods. (Author’s collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This cupboard contains various examples of ceramics that have been documented in seventeenth-century Jamestown and related colonial settlements through archaeological findings. Among the objects are brightly colored Italian Montelupo dishes, Northern Italian slip-decorated costrels, Spanish Hispano Moresque scudella, German stonewares from Frechen and the Westerwald region, Portuguese tin-glazed earthenware, English Borderware, and Dutch and English delft. Of special note are the 1610–1640 Chinese porcelain wine cups of the type excavated at Jamestown, Virginia, and other early Chesapeake-area sites.

A china closet interior in the Green Chamber of the Kelton House. (Author’s collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This cupboard contains examples of early- to mid-seventeenth-century Portuguese tin-glazed earthenwares of the type documented in American colonial sites in the Chesapeake region and New England. Other blue-and-white wares include English delft decorated in imitation of Chinese Ming porcelain.

Dish fragment, Montelupo, Italy, 1630–1650. Tin-glazed earthenware. D. 9". (Courtesy, Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities, the Reverend Richard Buck Site Collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Dish, Portugal, ca. 1660. Tin‑glazed earthenware. D. 10". (Courtesy, Virginia Department of Historic Resources; photo, Robert Hunter.) This example was excavated near Jamestown, Virginia.

A view of Drayton Hall from the Ashley River, Charleston, South Carolina, built 1754. (Photo, Robert Hunter.) The earlier dwelling of Francis Yonge, which was razed prior to the construction of Drayton Hall, was situated on the same location

Pièrre Eugene du Simitiere (1736–1784; b. Pierre-Eugène du Cimetière), Drayton Hall S.C., dated 1765 on reverse. Watercolor on paper. 8 3/8 x 12 1/2". (Courtesy, J. Lockard Collection; photo, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation and Craig McDougal.) The watercolor depicts the original design and eighteenth-century appearance of Drayton Hall, North America’s earliest example of fully executed Palladian architecture.

Sarah Stroud Clarke, Drayton Hall archaeologist and curator of collections, excavating a ditch feature that predates the ca. 1750 Drayton Hall. (Courtesy, Drayton Hall Preservation Trust.)

Teapot fragments, attributed to Pieter Adriaensz. Kocks (active 1701–1703), made by The “Greek A” Factory, Delft, Netherlands, 1701–1722. Tin-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Drayton Hall, National Trust for Historic Preservation.) A total of six fragments were excavated. The one on the left is two fragments joined.

Teapot, marked by Pieter Adriaensz. Kocks (active 1701–1703), made by The “Greek A” Factory, Delft, Netherlands, 1701–1722. Tin-glazed earthenware. H. 4 3/4". (Courtesy, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.)

Teapot, marked by Pieter Adriaensz. Kocks (active 1701–1703), made by The “Greek A” Factory, Delft, Netherlands, 1701–1722. Tin-glazed earthenware. H. 4 7/8". (Author’s collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the mark on the bottom of the teapot illustrated in fig. 11.

Robert Aronson, Michelle Erickson, Joseph Gromacki, Carter Hudgins, and Luke Beckerdite examine the black delft teapot fragments from Drayton Hall during The Winter Show, Park Avenue Armory, New York, New York, 2019. (iPhone photos, Robert Hunter.)

Black delft teapots shown together in the gallery of the Rijksmuseum for comparison. (Photo, Robert Aronson.)

Left to right: Joseph Gromacki, Robert Aronson, Michelle Erickson, Sarah Stroud Clarke, and Carter Hudgins in front of the Library of the Drayton Hall Preservation Trust. (Photo, Robert Hunter.)

Sarah Stroud Clarke, Robert Aronson, Joseph Gromacki, and Carter Hudgins participate in the initial comparison of the Drayton Hall fragments with the antique black delft teapot. (Photo, Robert Hunter.)

The author and Michelle Erickson compare the Drayton Hall teapot base fragment with the intact antique teapot (Photo, Robert Hunter.)

A close look at how the Drayton Hall fragment compares in size with the foot rim of the antique teapot. (Photo, Robert Hunter.)

Lacquer box, Japan, Edo period (seventeenth century). Lacquerware. W. 8 1/4". (Courtesy, Christie’s.) This gourd-shaped box was made for the Dutch market.

Namban tankard, Japan, Momoyama or early Edo period (ca. 1600–1620). Lacquerware. H. 7 1/4". (Courtesy, Victoria and Albert Museum.)

Teapot, Jingdezhen, China, 1690–1710. Hard-paste porcelain. H. 6Q÷8". (Courtesy, Reeves Museum of Ceramics, Washington and Lee University; photo, Brian Muncy.) Bamboo, pine, and prunus blossoms, which together are known in China as “the three friends of winter,” decorate the molded panels on this tea- or wine-pot. Because they remain evergreen or bloom in early spring, they symbolize perseverance, strength, and rebirth. They also represent the integrity and character of Chinese Confucian scholar-officials. Unusual pots like this were prized as exotic curiosities in Europe; the architect and designer Sir William Chambers chose to include an identical pot in one of two plates illustrating Chinese ceramics that he included in his “Designs of Chinese Buildings, Furniture, Dresses, Machines, and Utensils,” published in 1757 (see fig. 22).

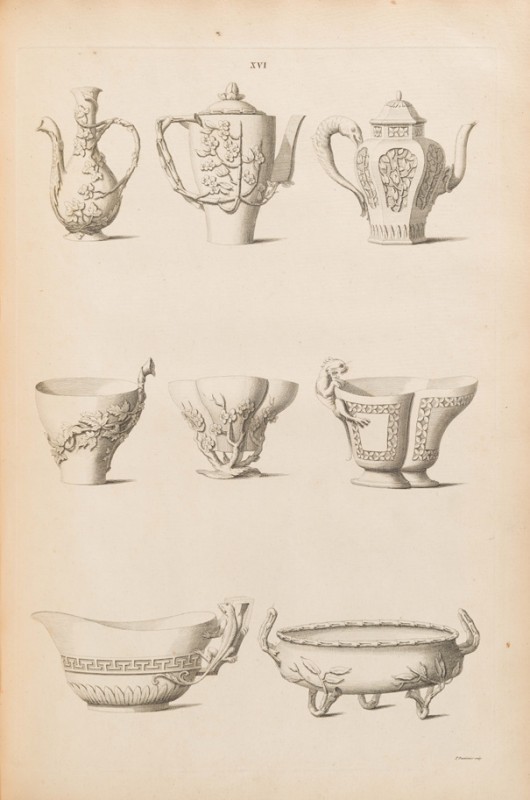

Plate XVI from William Chambers, Designs of Chinese Buildings, Furniture, Dresses, Machines, and Utensils, London, 1757. (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg.)

Teapot, Meissen porcelain factory, Germany, 1710–1713. Red stoneware. H. 6". (Courtesy, Victoria and Albert Museum.) The teapot is made in the stoneware body developed by the alchemist Johann Friedrich Böttger. Black-glazed wares were among the very first Meissen productions offered for sale at the Leipzig Easter Fair in 1710, when they were described in the Leipzig Gazette as “lacquered like the most beautiful Japanese products.”

Teapot, Metalen Pot factory, Lambertus van Eenhoorn (proprietor), Delft, ca. 1700–1724. Tin-glazed earthenware. H. 5 1/2". (Courtesy, Victoria and Albert Museum.)

Teapot bodies that have been fired to bisque tempetures and are awaiting glazing. (Photo, Robert Hunter)

Liquid wax is applied to the underside of the foot ring to prevent the glaze from coating the bottom. This keeps the base free from the raw glaze coating so during firing it can rest on the foot without sticking to the kiln shelf. The wax has been colored green to make it readily visible, since the glaze will not adhere wherever the wax is applied, intentionally or accidentally. (Photo, Robert Hunter.)

Liquid wax is also applied to the underside rim of the lid’s flange. The lid must be fired separately from the teapot and will rest on the unglazed bottom of the flange in the kiln to prevent it from sticking to the shelf. (Photo, Robert Hunter.)

The teapot is immersed in the tin glaze and allowed to drain thoroughly. A small plug of wax is inserted into the opening of the spout and over the interior opening to prevent the raw liquid glaze from flowing into the spout and blocking the openings once fired. (Photo, Robert Hunter.)

The lid undergoes the same process of glazing. Note how the green wax resists the glaze. The tiny steam holes are also blocked with wax to keep the glaze from filling them. (Photo, Robert Hunter.)

The bodies and lids are thoroughly dried. Michelle Erickson uses her finger to carefully rub down the tong marks and drips to even the decorating surface without disturbing any other areas. The teapots are now ready for decoration. Note the powdery surface of the glaze. (Photo, Robert Hunter.)

The outlines of the decoration are first marked on the pot using food coloring, beginning with the lightest yellow so that corrections can be marked in a different color. The food coloring subsequently burns off in the kiln, leaving no trace. (Photo, Robert Hunter.)

The decoration is done with high-temperature metallic oxide slips developed to match the original. Here the design is outlined in black and red slips accordingly and then filled with the colored slips of iron red, chrome green, and cobalt blue. (Photo, Robert Hunter.)

An iron-rich black ground slip is applied around the detailed outlines of the decoration to create the reserves. The remainder of the background is then filled in with black ground slip. (Photo, Robert Hunter.)

A group of reproduction black delft teapots, Michelle Erickson, Hampton, Virginia, 2020. (Photo, Robert Hunter.)

Beaker, Jingdezhen, China, ca. 1720. Hard-paste porcelain with underglaze blue. H. 3 3/8". (Courtesy, Drayton Hall, National Trust for Historic Preservation; photo, Jason Copes.) Archaeologically recovered from Drayton Hall excavations associated with Francis Yonge’s occupation of the property.

Teapot (lacking cover), marked by Pieter Adriaensz. Kocks (active 1701–1703), made by The “Greek A” Factory, Delft, Netherlands, 1701–1722. Tin-glazed earthenware. H. 4 1/8". (Author’s collection; photos, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the teapot illustrated in fig. 36, showing the decoration of the cherub’s head below the spout. (Photo, Robert Hunter.)

Detail of the teapot illustrated in fig. 36, showing the mark of Pieter Adriaensz. Kocks, The “Greek A” Factory. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

The most recently discovered black delft teapot, illustrated in fig. 36, with the replacement cover produced by Michelle Erickson. H. 5 1/2". (Author’s collection; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Introduction

I am a collector of seventeenth- and early-eighteenth-century American furni--ture and related decorative arts, including ceramics, textiles, base-metal wares, and the like. My collection contains examples of American furniture and related decorative arts of the kind used in colonial American households, primarily from the earliest periods of the upper, middle, and southern colonies (fig. 1). My passion for collecting art and decorative arts of this period and region results from the confluence of my deep interest in American history and my art and art-historical interests.[1]

UNTIL FAIRLY RECENTLY, many museums and collectors focused their ceramics collections exclusively or primarily on material of British and sometimes Dutch origin. My collection includes British and Dutch ceramics, but it also reflects the rich diversity of material that was reflective of the early colonial period in Britain and America, as documented in archaeological evidence from early settlement sites along the Eastern seaboard (figs. 2, 3).

Throughout the seventeenth century, there was a robust and complex global economy that may not be fully appreciated by modern historians and collectors. In the early seventeenth century, goods used in colonial America came from around the globe: Belgium, China, England, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal, and Spain. The diverse origin of those goods being shipped to the colonies reflected the numerous and extensive trade routes in operation at the time. In Jamestown, Virginia—the site of the earliest permanent English settlement in the New World—where shipping was restricted primarily to English vessels, the imported ceramics reflected the cosmopolitan nature of London at that time.[2]

The primary focus of my ceramics collection is material that was used in the American colonies before the implementation of the Navigation Acts (initially adopted in 1651 but not fully developed and enforced until several decades later), which dramatically altered the trade patterns to and from America (figs. 4, 5). This period essentially commenced in 1607, with the founding of the Jamestown settlement, and concluded around the end of the seventeenth or early eighteenth century.

The collection is informed primarily by the archaeological work conducted at Jamestown, although I draw on similar archaeological work in other significant early colonial settlement sites in the Chesapeake region, such as St. Mary’s City in Maryland.[3] I also consider the archaeological findings of Boston, New York, and Philadelphia.[4] Of particular relevance to the present story is certain archaeological work conducted at an important site in the vicinity of Charleston, South Carolina.[5]

Drayton Hall in South Carolina

Some years ago, I became aware of an exciting archaeological discovery at Drayton Hall (fig. 6), located outside Charleston. Drayton Hall exists today as an important—even iconic—eighteenth-century plantation located on the shores of the Ashley River, roughly fifteen miles northwest of Charleston, in an area sometimes referred to as the Lowcountry.

Drayton Hall is an outstanding example of Palladian architecture and represents the only plantation house on the Ashley River to survive intact through both the Revolutionary and the Civil Wars (fig. 7). Originally, the plantation, which served as a country seat for the Drayton family, consisted of roughly 750 acres. The family owned other large cash crop–producing tracts of land throughout South Carolina, and established its wealth based largely on indigo and rice production. Until recently, it was believed that Drayton Hall was begun in 1738 and completed in 1742. However, an examination in 2014 of wood cores from the attic of the house showed that the attic timbers were felled in the winter of 1747–1748. The house, now thought to have been constructed around 1754, passed through seven generations of the Drayton family before its sale to the National Trust for Historic Preservation in 1974, and it is now a National Historic Landmark. Its current steward is the Drayton Hall Preservation Trust, which manages the property and the associated museum.[6]

Of central relevance to this story, however, is the history of the property before the construction of Drayton Hall. John Drayton (1715–1779) purchased the property on March 2, 1738. Based on a 1737 advertisement for the property, it is clear that structures were present at the time of purchase. The advertisement references a “very good Dwelling house, Kitchen, and several out-houses, with a very good orchard consisting of all sorts of fruit trees.”[7] Documentary and archaeological research reveals that from 1718 to 1734 the owner of the property was Francis Yonge, the first regular colonial agent for South Carolina. Yonge served as South Carolina’s surveyor general from 1716 to 1719, and as colonial agent from 1721 to 1733.[8] Very little is known about Yonge’s material world, pending further archaeological excavations. His house was razed sometime before the building of Drayton Hall, which was to occupy the same general footprint.

The Fragments from the Pre–Drayton Hall Site

As a colonial agent, it is likely that Yonge frequently traveled to London on behalf of South Carolina colonists during his term of office. This transatlantic mobility likely accounts for the rare and sophisticated material culture found in pre–Drayton Hall archaeological contexts at the site (fig. 8). Of particular note and relevance is the discovery on the site of six fragments from an early-eighteenth-century Dutch black delft teapot (fig. 9). One of the fragments is part of the foot rim, another is part of the handle (where it meets the body of the teapot), and the remaining fragments are pieces of the body. Several of the fragments include polychrome floral or other decoration in blue, green, and iron-red enamels. The background glaze color of all the fragments is black.

Sarah Stroud Clarke, an archaeologist and director of museum affairs for Drayton Hall, recounts the discovery and realization of the significance of these ceramics fragments:

During the fall of 2009, archaeological excavations were underway at Drayton Hall when several tiny unknown fragments of what appeared to be tin-glazed earthenware were discovered in a ditch feature predating the Drayton period of ownership, which began in 1738. The mystery of the artifacts was that the exterior glaze not only had bright, polychrome decoration, but the surrounding color was black instead of the common pale-blue or white background found on most delft wares. Director Carter Hudgins and I are well versed in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century material culture, but we had never come across a tin-glazed ceramic with this type of exterior appearance. Drawing upon our network of friends and colleagues, we reached out to archaeologists also familiar with this time period, beginning with Bly Straube and Hugo Blake, who in turn sent the inquiry to Michael Archer and Paul Courtney. Everyone agreed that it must be Dutch, but no one had firsthand knowledge of what had been discovered at Drayton Hall. In January 2010, Paul Courtney replied to all simply stating, “See refs to black Delft backgrounds in: Delft Ceramics, by Caroline Henriette de Jonge, 1970.”[9] I starting searching for a copy of the noted book and ended up on the phone the next day with a librarian at the Swem Library on the campus of the College of William and Mary, the closest library to Charleston that contained a copy of Delft Ceramics The librarian was kind enough to pull the book, make copies of the pertinent pages, and fax them to Drayton Hall. It was then, in a black-and-white photograph on page 91, that we realized what we had found at Drayton Hall. “Chapter VIII: Polychrome Delft Faience on Dark Brown, Olive-Green or Black Background. Never Blue Faience: 1670–1740” begins with a statement in parenthesis: “Almost all black faience objects are now either in museums or privately owned and it is very unlikely that new pieces will be discovered.” The North American historical archaeology network was stumped because no one had ever seen this material archaeologically. Experts in the field estimate that [there] are less than seventy known intact vessels left of black delft in the world.

The reference to Delft Ceramics was the starting point that Sarah needed, as the picture that so closely matched the fragments found at Drayton Hall was of a teapot from the Rijksmuseum, marked “PAK” from De Grieksche A (The Greek A) factory and dated 1701–1722 (fig. 10). News of the discovery spread among archaeologists and it was published in Ceramics in America in 2017.[10] Knowing of the archaeological finding of these fragments, I have long sought to acquire for my collection a Dutch black delft teapot that corresponds to the fragments excavated at the Drayton Hall site. Having made numerous inquiries of various antiquarian dealers and having monitored the auction market over the years, I had been of the view that it would be exceedingly difficult, perhaps impossible, to find such an object due to the incredible paucity of extant Dutch black delftware in general and the low likelihood of finding a piece that corresponded meaningfully to the archaeological fragments from the Drayton Hall site. For years, I was aware of only the teapot in the Rijksmuseum collection as corresponding to these fragments.

All that changed in December 2018.

A Discovery in Amsterdam

In December 2018 I traveled to Amsterdam for a winter holiday, and I went to Delft, Edam, Haarlem, the Hague, Leiden, Marken, Oudewater, and Rotter-dam as well. I visited many of the great fine and decorative arts museums of the Netherlands to see and study examples of Dutch delftware and other material of interest to me.

While in Amsterdam, I made an appointment to visit the gallery of the Aronsons, a renowned family of antiquarians who have been dealers of the highest quality Dutch delftware for five generations. Their firm, known as Aronson Antiquairs, was founded in 1881 and they have placed many extraordinary ex-amples of Dutch delftware in important private and public collections.

I spent time with Robert Aronson, the current proprietor of the establishment, and mentioned my interest in acquiring a black delft teapot relating to the Drayton Hall fragments. We discussed in detail the rarity and historical importance of Dutch black delft. I showed Mr. Aronson an image of the fragments from Drayton Hall as well as an image of the black delftware teapot in the collection of the Rijksmuseum, with which he was already familiar.

Shortly before I was to return to America, Mr. Aronson requested a private meeting, at which time he revealed the existence of another Dutch black delft teapot (fig. 11). This example was very similar in form, size, and decoration to the example in the collection of the Rijksmuseum and to the Drayton Hall site fragments.[11] It also had the “PAK” mark from the “Greek A” factory (fig. 12). Mr. Aronson shared with me an image and description of the teapot, and noted that the owner was advanced in age and might consider parting with this object, particularly after being advised of my keen interest and the important and unique relevance to American history due to the archaeological fragments found at the Drayton Hall site. Needless to say, I expressed a strong desire to learn more about the piece.

Research and Study of the Teapot

An exchange of information and a discussion pertaining to black delftware in general then transpired between Mr. Aronson and me. My advisers—among them Robert Hunter, editor of Ceramics in America; Michelle Erickson, a potter, ceramic artist, and historical ceramics scholar; and Luke Beckerdite, an independent scholar and the editor of American Furniture, published by the Chipstone Foundation—participated in this dialogue and study of the black delftware teapot. As custodians of the fragments that had been excavated at the Drayton Hall site, Carter Hudgins, president and chief executive officer of the Drayton Hall Preservation Trust, and Sarah Stroud Clarke, director of museum affairs of the Drayton Hall Preservation Trust, also engaged in this discourse, providing valuable information about the pre–Drayton Hall fragments.

In January 2019, at my request, Mr. Hudgins brought five of the six fragments of the black delft teapot to New York City for the purpose of examining them with Mr. Aronson, Mr. Hunter, Ms. Erickson, Mr. Beckerdite, and myself. Although I had inquired about the possibility of Mr. Aronson bringing the black delftware teapot to New York City, it was not possible due to the requirement of an export license from the authorities in the Netherlands and the time required to obtain it. We thus relied on the images of the black delftware teapot in the possession of Mr. Aronson as well as his knowledge of the object based on his personal examination.

In a back room of the Park Avenue Armory, which was then hosting the Winter Show at which Aronson Antiquairs was exhibiting, this group assembled and carefully examined the fragments (fig. 13). An exciting revelation occurred. It became clear that the decoration on the fragments related more closely to the decoration on the teapot in the private European collection than to that on the teapot in the Rijksmuseum collection. Ms. Erickson’s input, from the perspective of an accomplished ceramic artist, was instrumental in helping us to reach this conclusion with regard to the character of the decoration. Further, by scanning scaled images of the fragments and comparing them to the images of the teapot in the private European collection, it became clear that the size and scale of the teapot corresponded closely to the size and scale of the teapot to which the fragments were associated. Measurements would be required in order to confirm this, but it seemed likely based on the available information.

Further correspondence regarding the teapot ensued over the next few weeks, even after Mr. Aronson returned to Amsterdam. The communications related to the rarity of Dutch black delftware generally, the known intact pieces of Dutch black delftware (in public and private collections), the known objects associated with the so-called Greek A factory in Delft, those objects bearing the “PAK” mark, and the degree to which the fragments excavated at the Drayton Hall site related to the teapot in the private European collection. Based on the collective knowledge of this group, only two extant spherical-form black delft teapots existed from the “Greek A” factory: the teapot in the private European collection and the teapot in the collection of the Rijksmuseum.

We were fortunate that one of the fragments from the Drayton Hall site was a piece of the foot rim of that teapot. From scaling the fragment using an archaeologists’ circumference- and diameter-measuring mat, and getting the actual measurements of the black delft teapot in the private European collection, it was possible to confirm that the latter teapot had a base diameter within roughly five or six millimeters of that of the teapot to which the fragments related. This confirmed that the two pieces were of nearly identical size and scale. Of course, this determination enhanced my level of interest in the teapot in the private European collection.

Once back in Amsterdam, Mr. Aronson contacted the Rijksmuseum and requested an opportunity to examine the black delft teapot in their collection. This examination took place on February 4, 2019, after the museum had closed to the public. Mr. Aronson brought with him to the Rijksmuseum the black delft teapot from the private European collection, and photographed the two teapots together in the gallery of the museum; he subsequently shared those images with me and my advisers (fig. 14).

The comparison of these two pieces by Mr. Aronson and the Rijksmuseum curator Femke Diercks was highly informative. Among other things, it confirmed the likelihood that the two teapots were decorated by the same hand. Although the decoration on the Rijksmuseum teapot was in certain ways more formalistic in design, both teapots used precisely the same palette of glaze colors and the same decorative elements, consisting primarily of blue and iron-red flowers, blue and green leaves, and cherubs in blue, along with rows of spiral/whorl decorations in iron red. Additionally, both pieces shared the “PAK” mark on the bottom. Finally, the base diameters of the two teapots were confirmed to be within roughly two millimeters of each other. The close relationship between the two Dutch black delftware objects was remarkable. In fact, Ms. Diercks, upon seeing the two pieces together, commented, “gebroederlijk naast elkaar,” which translates roughly to mean “brotherly side by side.”

The Acquisition

In view of the foregoing analysis and conclusions, arrangements were made for Mr. Aronson and me each to travel to Charleston for a meeting on February 14, 2019, for the purpose of examining the fragments from the Drayton Hall site and comparing them with the actual teapot in the private European collection. By this time, the necessary export license for the teapot had been obtained by Mr. Aronson and the piece could travel to America.

Mr. Hunter, Ms. Erickson, Mr. Hudgins, and Ms. Stroud Clarke participated in the meeting, which took place in the library of the Drayton Hall Preservation Trust (fig. 15). At this time, images taken in the galleries of the Rijksmuseum of its teapot and the teapot from the private European collection were reviewed. The group compared carefully the decoration on the fragments to that on the teapot from the private European collection (fig. 16). The resemblance—in terms of form, decoration, and composition—was extraordinary (figs. 17, 18).

The group subsequently toured Drayton Hall itself, the Drayton Hall site, and the excavation site where the fragments had been discovered, along with Trish Smith, curator of historic architectural resources of the Drayton Hall Preservation Trust. At the end of the day, I made the decision to acquire the black delft teapot for my collection. It was a thrilling moment and I believe that all present shared in the excitement.

The History and Significance of Dutch Black Delft

For any collector, the acquisition of an important object is often only a springboard for additional research and exploration. It is worth considering at least briefly the background of Dutch black delftware and how it came to exist. In the seventeenth century, porcelain, lacquer, and silk were among the exotic and precious objects from China and Japan that were coveted by those in faraway Europe. Especially during the era when trade flourished over land via the Silk Road or by sea, these products were among the most sought-after luxury goods, especially by the courts of Europe.

Early in the seventeenth century, the Dutch East India Company (VOC) introduced Japanese lacquerwork to the Dutch Republic and other places in Europe, much as it had done with Chinese porcelain. Japanese lacquerware is made from the sap of the lacquer (urushi) tree, native to China but cultivated in Japan. Urushi sap is a highly resistant and durable material that can be molded into a number of decorative and utilitarian forms (figs. 19, 20).

When the Dutch arrived in Japan in roughly 1600, they established commercial relations with the Japanese. Within a few years they recognized the high quality of Japanese lacquer and its general scarcity in northern Europe. Because there was a keen interest in East Asian curiosities among Dutch buyers, VOC merchants predicted that Japanese lacquer might become a profitable item for export. Unlike Asian porcelain, however, Japanese lacquer was extremely expensive and never really became a common part of Dutch material culture.

Black-glazed delftware undoubtedly was inspired by these Chinese famille noire porcelains of the Kangxi period (1662–1722) (figs. 21, 22), about which comparatively little has been written.[12] It is basically a subset of enamel on biscuit (low-fired enamels painted onto a high-fired but un-glazed porcelain body) and was probably designed to imitate or at least reference lacquer. The black color is created by painting a layer of translucent copper green over a dark manganese and iron-brown layer to create a black colored ground; it is an evolution of colors (often known as sancai [lit. “three colors”]) developed in the Ming dynasty. It is this full palette of colors that the Delft potters sought to deploy to enliven or act as a counterpoint to the gleaming dark glaze of their “Black Delft.”

Although Japanese lacquerware was very expensive, the small amounts of it that were bought by the VOC merchants in Japan did ignite curiosity and inspiration in northern Europe, including Holland. The European vogue for lacquer that began in the late seventeenth century coincided with the taste for trompe l’oeil eVects, with the result that lacquerware was imitated in a variety of ways and with a diverse array of materials, such as wood, metal, earthenware, and stoneware (fig. 23).

In the city of Delft, where the production of “porcelain” for the national and export market began with the manufacture of products with a shiny white ground with blue painted decoration, potters were inspired by these exotic lacquerwares and started experimenting with different colors of glazes.[13] From the 1680s onward, the great challenge driving the technical development and use of colors, such as black, was the introduction of the highly desirable but expensive Japanese kakiemon and Imari porcelain. By 1690, it had become increasingly difficult for the VOC to obtain high-quality, affordable Asian lacquerware and the trade in it thus declined. Despite this problem, household inventories of the time show that wealthy, fashion-conscious Dutch townspeople were keen to imitate the court and surround themselves with such exotic objects.

As discussed by Marion van Aken-Fehmers in her authoritative essay “Objects of the Highest Esteem: Delft Black ‘Porcelain,’ 1700–1740,” a 1649 document from the municipal archives shows that Delft potters were already using the typical green, blue, yellow, red, and black glazes.[14] Roughly thirty years later, a treatise was published by the German chemist Johannes Kunckel (1630–1702/3), a German chemist who directed the laboratory and glassworks at Brandenburg and who in 1679 wrote Ars vitraria experimentalis: Oder Vollkommene Glasmacher-Kunst, in which he recorded the recipes for fine glazes used on Dutch “porcelain.”[15] In one of the thirty-six chapters dedicated to colored glazes, Kunckel discussed the formula for the black color and chronicled the difficulty in obtaining a perfect black shine.[16] He observed that manganese oxide, the mineral used to obtain the black color, does not react well with some of the other colored glazes used on delftwares, suggesting that the technique of producing a true black colored glaze was extremely difficult. Because of the difficulty of producing black glaze, it is believed that very few factories either attempted it or were successful at it. Those factories that mastered the technique of making black delftware managed their practices as a carefully guarded proprietary trade secret.

Today only about seventy examples of Dutch black delft survive, and most of those are not marked. Forms of black delftware include teaware—teacups and saucers, tea canisters, teapots, and coffeepots—as well as brush backs and larger items such as dishes and plaques.

Two techniques of production have been identified for the black delft produced by various Dutch factories. One consisted of covering the object completely in a black glaze and then applying the enamel decoration onto the black ground. The black glaze was applied directly to the bisque ware, and then, once the glaze was dry, the painter decorated the piece with enamel colors. However, only a limited number of colors were compatible with this technique, and most extant black delft pieces utilizing this method of production are thus decorated with yellow, blue, and white (red and green did not react well with the manganese oxide). To achieve those colors, a white primer coat was applied over the black glaze in order to mitigate its toxic impact. One crucial factor was the firing temperature: if it was too low, the colors could appear very dull against the dark background. This challenge was exacerbated by the lack of a reliable tool to measure accurately the temperature in the kiln. Marked objects using this technique of glazing were produced mainly by De Metaale Pot (The Metal Pot) in Delft, a factory owned by Lambertus van Eenhoorn from 1691 to 1724. One example of its output, a teapot now in the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum, is illustrated in figure 24. Most of the Dutch black delft wares produced using this first technique directly copied Asian iconography for the enamel decoration.

The second technique appears to be restricted to the products of the “Greek A” factory during the ownership of Pieter Adriaensz. Kocks, from 1701 to 1703. (After Kocks died in 1703, his widow, Johanna van der Heul, took ownership of the factory until she sold it in 1722; during that time, she apparently continued to use the “PAK” mark.) The pieces associated with that factory were fired initially with a layer of white tin glaze and applied with polychrome enamels before the blank areas around the decoration were filled in with a black glaze, as can be seen in the decoration of this teapot. Somewhat at odds with the decorative scheme of other European lacquerware imitators, the examples produced during Kocks’s tenure at the “Greek A” factory incorporated Baroque decorative elements of floral garlands, cherubs, or putti. A putto is a figure in a work of art depicted as a chubby male child, usually naked and sometimes winged. Originally limited to profane passions in symbolism, the putto came to represent the sacred cherub (pl. cherubim), and in Baroque art represented the omniscience of God.[17]

Making a Black Delft Teapot

For this article, Michelle Erickson has shared her experience with the reproduction of black delft to help illustrate the decorating techniques used in the “Greek A” factory. She first created a number of the teapot forms using the dimensions of the newly acquired antique example.

After the form is thrown on the wheel and assembled with handle, spout, and lid, it is fired to a bisque temperature (fig. 25). After firing, the bisque ware is prepared for glazing by coating the base and lid rim with a liquid wax to prevent the glaze from sticking (figs. 26, 27). The teapot body and lid are then dipped into a tin glaze bath and allowed to dry (figs. 28–30).

At this point, the raw glazed surface is ready to receive the decoration. Since the surface is highly friable, Ms. Erickson first marks the design on the surface of the teapot using food coloring, which helps determine the composition and spacing of the design elements (fig. 31). The food coloring burns away in the final glaze firing.

Decorating begins with the putti figures, flowers, leaves, and branches. These decorative elements are outlined in black and subsequently filled with colored oxides of red, green, blue, and yellow. The intricate scrolls around the base and rim and on the lid are the last elements to be painted in (fig. 32).

At the final stage, the black colored glaze is carefully applied around the colored decoration (fig. 33). A white reserve is left between the polychrome decoration and the dark glaze, and effectively becomes part of the decoration. After decorating, the teapot and lids are given a final firing. A group of Ms. Erickson’s fired examples are illustrated in figure 34.

Conclusion

Mastering the very costly undertaking of producing Dutch black delftware was an artistic tour de force achieved by only a few factories in Delft. As outlined above, the development of black delftware arose from the long-held fascination of Europeans with the East, and the fantastic and exotic decoration on these wares reflects the Dutch aesthetics of the time. Rare and precious, Dutch black delftware was a highly sought-after luxury good when it was produced.

In the early 1700s, when the Drayton Hall teapot (now in fragments) was produced, procured, and brought to America, presumably by Francis Yonge, it would have been considered an expensive and rare luxury item. The exotic nature of its appearance, reminiscent of the influence of precious Japanese and Chinese objects, would have made a strong impression on all who saw it, and it would have conveyed the social stature and sophistication of its owner, FrancisYonge. Tea itself was an expensive luxury good at that time, and teapots were also made in expensive and elaborate formats, as was the case with this piece. In describing the allure of black lacquer and its imitators, Dutchman Simon De Vries wrote in 1692 that black domestic furnishings were the choice of “great and distinguished people” and command “the highest esteem.”[18]

Yonge’s material world may be further revealed through future excavations and documentary research.[19] A hint of that world is provided by the early-eighteenth-century Chinese porcelain beaker thought to be related to the Yonge family occupation of the Drayton Hall property.[20] That object (fig. 35) reflected the allure of Chinese porcelain for South Carolina’s Lowcountry elite, as well as for the British gentry. Trade laws of the day mandated that Chinese and other imported goods be moved through a British port before their reshipment to America. As Yonge traveled to England regularly on colony business, those trips and his wealth gave him access to such luxury goods. Perhaps the beaker shared the tea table with the black delft teapot, a combination of the finest luxury ceramics that the world market could provide at that time. Certainly, their presence would have been emblematic of the wealth, sophistication, and refined aesthetics of American colonists in the early eighteenth century.

I believe that the teapot I have acquired is important as one of the most rare and costly ceramic objects that can be proven to have existed in the American colonies at that early date. Its beauty as an object speaks for itself. Understanding the complexities associated with its production and its rarity as a surviving object make the teapot even more special. Further, I find it remarkable that this is only the second time in roughly three hundred years that a rare black delftware teapot of this sort traveled to America from the Netherlands. I am proud to have added this piece to my archaeologically based collection of ceramics used in the American colonies during the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, and I sincerely hope that publication of its existence will contribute in a meaningful way to the appreciation of American material culture and history of this period.

A Postscript

Several months after my acquisition of the rare black delft teapot discussed above, something most unexpected occurred: Robert Hunter called me to indicate that he had become aware of the possible existence of a third early-eighteenth-century Dutch black delft teapot, with similar polychrome decoration and bearing the “PAK” mark of the “Greek A” factory (fig. 36). Although lacking its lid, the newly discovered piece had apparently resided for many years in the collection of an English ceramics collector who was considering selling the object. Eventually, thorough the auspices of Rob Michiels Auction in Brugge, Belgium, I was able to acquire the teapot.[21] Robert Aronson kindly assisted in coordinating the appropriate conservation of this object after I purchased it. Following its conservation by an expert in Amsterdam, the object was delivered to me personally in the United States by Mr. Aronson in October 2019.

The piece is a bit larger in scale than the other two examples, but features decoration that is likely by the same hand; the colors and motifs bear significant similarity to the decoration on the other examples. Specifically, it utilizes the same palette of glaze colors and the same decorative elements, consisting primarily of blue and iron red flowers, blue and green leaves, and cherubs in blue and white, as well as rows of spiral/whorl decorations in iron red. Its decoration is particularly elaborate, with putti dominating the decoration (figs. 37, 38).

Some consideration was given as to whether a replacement lid should be fashioned for this important object. Ultimately, Michelle Erickson was called upon to create a lid. While some speculation was required in order to do this, she created a remarkable mate for this 300-year-old Dutch ex-ample, which now resides in my collection (fig. 39).

The discovery and my acquisition of the third black delftware teapot was as extraordinary as it was unexpected. Contrary to Dr. Caroline H. de Jonge 1969’s assertion that “it [is] very unlikely that new pieces will be discovered,” we now have another example of a Pieter Adriaensz. Kocks teapot. These three black delft teapots, each bearing the “PAK” mark, remain the only known examples to exist. Their survival is truly remarkable!

A C K N O W L E D G M E N T S I wish to express deep thanks to Robert Aronson, Luke Beckerdite, Sarah Stroud Clarke, Michelle Erickson, Carter Hudgins, Robert Hunter, Rob Michiels, Trish Smith, and Martha Zierdan for their extraordinary assistance in conducting this research and writing this article, as well as their help in facilitating this acquisition. I hope that my ownership and stewardship of this important object may also inure to the benefit of Drayton Hall and the Drayton Hall Preservation Trust in carrying out its vital mission.

An earlier version of this article was prepared for the Walpole Society. See Joseph P. Gromacki, “The Story of My Quest for a Rare Dutch Black Delftware Teapot,” The Walpole Society Notebook 2019 (New York: Printed by Ink for the Walpole Society, 2020), pp. 87–106.

Beverly A. Straube, “European Ceramics in the New World: The Jamestown Example,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2001), pp. 47–71; Merry Outlaw, “Jamestown and Governor’s Land, James City County, Virginia,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2017), pp. 248–69; Bly Straube, “Jamestown, Virginia: Virginia Company Period,” in ibid., pp. 186–204.

Martha W. McCartney, “George Thorpe’s Inventory of 1624: Virginia’s Earliest Known Appraisal,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2016), pp. 2–30; Silas Hurry, “Historic St. Mary’s City, Maryland,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2017), pp. 164–84.

Deborah L. Miller and Jed Levin, “Philadelphia, Pennsylvania,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2017), pp. 143–63; Meta F. Janowitz and Diana diZerega Wall, “New York, New York,” in ibid., pp 164–84.

Martha A. Zierden et al., “Charleston, South Carolina,” in ibid., pp. 22–39.

For more on Drayton Hall, visit its website at https://www.draytonhall.org.

Property advertisement, South Carolina Gazette, December 15, 1737.

Susan Baldwin Bates and Harriott Cheves Leland, eds., Proprietary Records of South Carolina, vol. 3, Abstracts of the Records of the Surveyor General of the Province, Charles Towne, 1678–1698 (Charleston, S.C.: History Press, 2007); Shi-pei Chu, “Francis Yonge: The First Regular Colonial Agent for South Carolina” (master’s thesis, University of South Carolina, 1960); Henry A. M. Smith, Rivers and Regions of Early South Carolina, The Historical Writings of Henry A. M. Smith 3 (Spartanburg, S.C.: Reprint Co., in association with the South Carolina Historical Society, 1988).

Caroline Henriette de Jonge, Delft Ceramics (New York: Praeger Publishing, 1969).

Zierden et al., “Charleston, South Carolina,” pp. 26–27.

Provenance for the collection history of the teapot includes The Frits Phillips Collection, “De Wielewaal,” Eindhoven, November 2006; Aronson Antiquairs, Amsterdam, 2007; private collection, Belgium, 2007–19; private collection, United States, 2019–present. The teapot was described and illustrated in Dave Aronson and Robert Aronson, Dutch Delftware 2007 (Amsterdam: Aronson Antiquairs, 2007), p. 28, no. 19; and Birte Abraham and Robert Aronson, Dutch Delftware: The Van der Vorm Collection, ed. Robert Aronson (Amsterdam: Aronson Publishers, 2010), pp. 106–7.

C. J. A. Jorg, “Chinese and Japanese Porcelain with Lacquer Decoration in the Dresden Porcelain Collection,” in Monika Kopplin, ed., Schwartz Porcelain: The Lacquer Craze and Its Impact on European Porcelain, English ed. (Munich: Hirmer, 2003), pp. 25–31.

“The Creation of the Exotic Black Delft,” available online at https://www.aronson.com/the-creation-exotic-black-delft/.

Municipal Archives of Delft, ONA 2066, doc. 4, September 27, 1649, not E. van def Vloet, as cited in Marion van Aken-Fehmers, “Objects of the Highest Esteem: Delft Black ‘Porcelain,’ 1700–1740,” in Kopplin, Schwartz Porcelain, p. 62.

Ars vitraria experimentalis: Oder Vollkommene Glasmacher-Kunst, 1st ed. (Frankfurt and Leipzig, 1679), pp. 49–65, as cited in Marion van Aken-Fehmers, “Objects of the Highest Esteem: Delft Black ‘Porcelain,’ 1700–1740,” in Kopplin, Schwartz Porcelain, p. 64.

Robert Aronson, Dutch Delftware: Including Selections from a Distinguished Manhattan Collector (Amsterdam: Aronson Antiquairs, 2009).

Charles Dempsey, Inventing the Renaissance Putto (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001).

Curieuse Aenmerckingen der Bysonderste Oost en West-Indische Verwonderens-Waerdige Dingen: Nevens die van China, Africa, en Andere Gewesten des Werelds, as cited in Aken-Fehmers, “Objects of the Highest Esteem: Delft Black ‘Porcelain,’ 1700–1740,” in Kopplin, Schwartz Porcelain, p. 64.

For additional background, see Martha Zierden and Ronald W. Anthony, Archaeological Testing, 2003, Drayton Hall, Archaeological Contributions 33 ([Charleston, S.C.]: Charleston Museum, 2004).

For additional background, see Martha Zierden and Ronald W. Anthony, Archaeological Testing, 2003, Drayton Hall, Archaeological Contributions 33 ([Charleston, S.C.]: Charleston Museum, 2004).

https://www.draytonhall.org/china-of-the-most-fashionable-sort-with-suzanne-hood/.

I am indebted to Rob Michiels (https://www.rm-auctions.com/en/home) and Robert Hunter for bringing to my attention the existence of this third black delft teapot.