Reconstructed ca. 1740 kitchen, Kelton House, Warwick, Massachusetts, twentieth century. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The house was moved to Wisconsin in the third quarter of the twentieth century.

Dresser, southeastern Pennsylvania, ca. 1750. Walnut and mixed woods. (Author’s collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This cupboard contains various examples of ceramics that have been documented in seventeenth-century Jamestown and related colonial settlements through archaeological findings. Among the objects are brightly colored Italian Montelupo dishes, Northern Italian slip-decorated costrels, Spanish Hispano Moresque scudella, German stonewares from Frechen and the Westerwald region, Portuguese tin-glazed earthenware, English Borderware, and Dutch and English delft. Of special note are the 1610–1640 Chinese porcelain wine cups of the type excavated at Jamestown, Virginia, and other early Chesapeake-area sites.

A china closet interior in the Green Chamber of the Kelton House. (Author’s collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This cupboard contains examples of early- to mid-seventeenth-century Portuguese tin-glazed earthenwares of the type documented in American colonial sites in the Chesapeake region and New England. Other blue-and-white wares include English delft decorated in imitation of Chinese Ming porcelain.

Dish fragment, Montelupo, Italy, 1630–1650. Tin-glazed earthenware. D. 9". (Courtesy, Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities, the Reverend Richard Buck Site Collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Dish, Portugal, ca. 1660. Tin‑glazed earthenware. D. 10". (Courtesy, Virginia Department of Historic Resources; photo, Robert Hunter.) This example was excavated near Jamestown, Virginia.

A view of Drayton Hall from the Ashley River, Charleston, South Carolina, built 1754. (Photo, Robert Hunter.) The earlier dwelling of Francis Yonge, which was razed prior to the construction of Drayton Hall, was situated on the same location

Pièrre Eugene du Simitiere (1736–1784; b. Pierre-Eugène du Cimetière), Drayton Hall S.C., dated 1765 on reverse. Watercolor on paper. 8 3/8 x 12 1/2". (Courtesy, J. Lockard Collection; photo, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation and Craig McDougal.) The watercolor depicts the original design and eighteenth-century appearance of Drayton Hall, North America’s earliest example of fully executed Palladian architecture.

Sarah Stroud Clarke, Drayton Hall archaeologist and curator of collections, excavating a ditch feature that predates the ca. 1750 Drayton Hall. (Courtesy, Drayton Hall Preservation Trust.)

Teapot fragments, attributed to Pieter Adriaensz. Kocks (active 1701–1703), made by The “Greek A” Factory, Delft, Netherlands, 1701–1722. Tin-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Drayton Hall, National Trust for Historic Preservation.) A total of six fragments were excavated. The one on the left is two fragments joined.

Teapot, marked by Pieter Adriaensz. Kocks (active 1701–1703), made by The “Greek A” Factory, Delft, Netherlands, 1701–1722. Tin-glazed earthenware. H. 4 3/4". (Courtesy, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.)

Teapot, marked by Pieter Adriaensz. Kocks (active 1701–1703), made by The “Greek A” Factory, Delft, Netherlands, 1701–1722. Tin-glazed earthenware. H. 4 7/8". (Author’s collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the mark on the bottom of the teapot illustrated in fig. 11.

Robert Aronson, Michelle Erickson, Joseph Gromacki, Carter Hudgins, and Luke Beckerdite examine the black delft teapot fragments from Drayton Hall during The Winter Show, Park Avenue Armory, New York, New York, 2019. (iPhone photos, Robert Hunter.)

Black delft teapots shown together in the gallery of the Rijksmuseum for comparison. (Photo, Robert Aronson.)

Left to right: Joseph Gromacki, Robert Aronson, Michelle Erickson, Sarah Stroud Clarke, and Carter Hudgins in front of the Library of the Drayton Hall Preservation Trust. (Photo, Robert Hunter.)

Sarah Stroud Clarke, Robert Aronson, Joseph Gromacki, and Carter Hudgins participate in the initial comparison of the Drayton Hall fragments with the antique black delft teapot. (Photo, Robert Hunter.)

The author and Michelle Erickson compare the Drayton Hall teapot base fragment with the intact antique teapot (Photo, Robert Hunter.)

A close look at how the Drayton Hall fragment compares in size with the foot rim of the antique teapot. (Photo, Robert Hunter.)

Lacquer box, Japan, Edo period (seventeenth century). Lacquerware. W. 8 1/4". (Courtesy, Christie’s.) This gourd-shaped box was made for the Dutch market.

Namban tankard, Japan, Momoyama or early Edo period (ca. 1600–1620). Lacquerware. H. 7 1/4". (Courtesy, Victoria and Albert Museum.)

Teapot, Jingdezhen, China, 1690–1710. Hard-paste porcelain. H. 6Q÷8". (Courtesy, Reeves Museum of Ceramics, Washington and Lee University; photo, Brian Muncy.) Bamboo, pine, and prunus blossoms, which together are known in China as “the three friends of winter,” decorate the molded panels on this tea- or wine-pot. Because they remain evergreen or bloom in early spring, they symbolize perseverance, strength, and rebirth. They also represent the integrity and character of Chinese Confucian scholar-officials. Unusual pots like this were prized as exotic curiosities in Europe; the architect and designer Sir William Chambers chose to include an identical pot in one of two plates illustrating Chinese ceramics that he included in his “Designs of Chinese Buildings, Furniture, Dresses, Machines, and Utensils,” published in 1757 (see fig. 22).

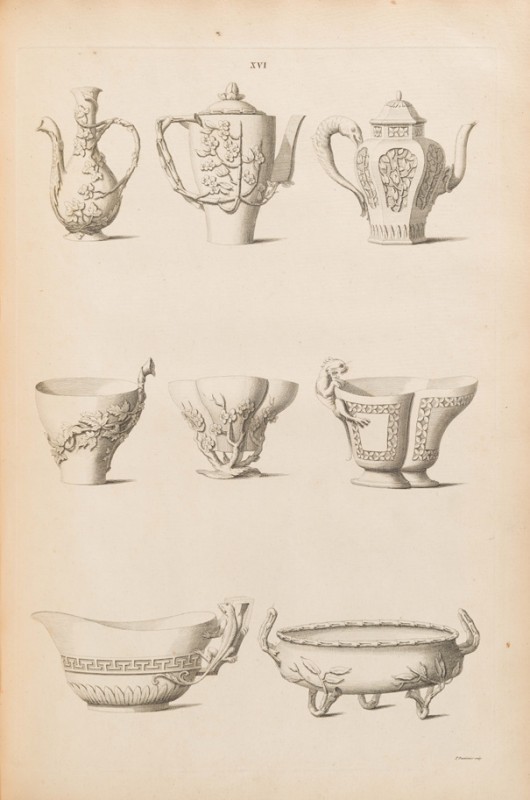

Plate XVI from William Chambers, Designs of Chinese Buildings, Furniture, Dresses, Machines, and Utensils, London, 1757. (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg.)

Teapot, Meissen porcelain factory, Germany, 1710–1713. Red stoneware. H. 6". (Courtesy, Victoria and Albert Museum.) The teapot is made in the stoneware body developed by the alchemist Johann Friedrich Böttger. Black-glazed wares were among the very first Meissen productions offered for sale at the Leipzig Easter Fair in 1710, when they were described in the Leipzig Gazette as “lacquered like the most beautiful Japanese products.”

Teapot, Metalen Pot factory, Lambertus van Eenhoorn (proprietor), Delft, ca. 1700–1724. Tin-glazed earthenware. H. 5 1/2". (Courtesy, Victoria and Albert Museum.)

Teapot bodies that have been fired to bisque tempetures and are awaiting glazing. (Photo, Robert Hunter)

Liquid wax is applied to the underside of the foot ring to prevent the glaze from coating the bottom. This keeps the base free from the raw glaze coating so during firing it can rest on the foot without sticking to the kiln shelf. The wax has been colored green to make it readily visible, since the glaze will not adhere wherever the wax is applied, intentionally or accidentally. (Photo, Robert Hunter.)

Liquid wax is also applied to the underside rim of the lid’s flange. The lid must be fired separately from the teapot and will rest on the unglazed bottom of the flange in the kiln to prevent it from sticking to the shelf. (Photo, Robert Hunter.)

The teapot is immersed in the tin glaze and allowed to drain thoroughly. A small plug of wax is inserted into the opening of the spout and over the interior opening to prevent the raw liquid glaze from flowing into the spout and blocking the openings once fired. (Photo, Robert Hunter.)

The lid undergoes the same process of glazing. Note how the green wax resists the glaze. The tiny steam holes are also blocked with wax to keep the glaze from filling them. (Photo, Robert Hunter.)

The bodies and lids are thoroughly dried. Michelle Erickson uses her finger to carefully rub down the tong marks and drips to even the decorating surface without disturbing any other areas. The teapots are now ready for decoration. Note the powdery surface of the glaze. (Photo, Robert Hunter.)

The outlines of the decoration are first marked on the pot using food coloring, beginning with the lightest yellow so that corrections can be marked in a different color. The food coloring subsequently burns off in the kiln, leaving no trace. (Photo, Robert Hunter.)

The decoration is done with high-temperature metallic oxide slips developed to match the original. Here the design is outlined in black and red slips accordingly and then filled with the colored slips of iron red, chrome green, and cobalt blue. (Photo, Robert Hunter.)

An iron-rich black ground slip is applied around the detailed outlines of the decoration to create the reserves. The remainder of the background is then filled in with black ground slip. (Photo, Robert Hunter.)

A group of reproduction black delft teapots, Michelle Erickson, Hampton, Virginia, 2020. (Photo, Robert Hunter.)

Beaker, Jingdezhen, China, ca. 1720. Hard-paste porcelain with underglaze blue. H. 3 3/8". (Courtesy, Drayton Hall, National Trust for Historic Preservation; photo, Jason Copes.) Archaeologically recovered from Drayton Hall excavations associated with Francis Yonge’s occupation of the property.

Teapot (lacking cover), marked by Pieter Adriaensz. Kocks (active 1701–1703), made by The “Greek A” Factory, Delft, Netherlands, 1701–1722. Tin-glazed earthenware. H. 4 1/8". (Author’s collection; photos, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the teapot illustrated in fig. 36, showing the decoration of the cherub’s head below the spout. (Photo, Robert Hunter.)

Detail of the teapot illustrated in fig. 36, showing the mark of Pieter Adriaensz. Kocks, The “Greek A” Factory. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

The most recently discovered black delft teapot, illustrated in fig. 36, with the replacement cover produced by Michelle Erickson. H. 5 1/2". (Author’s collection; photo, Robert Hunter.)