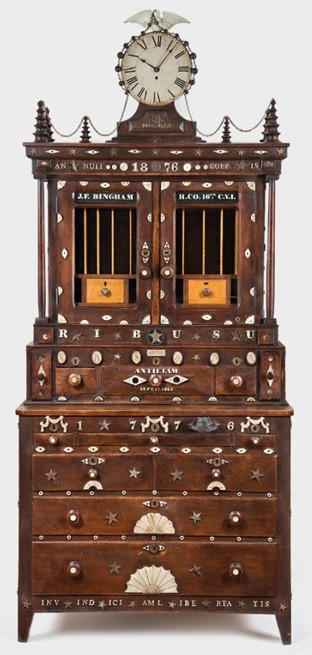

Harold Gordon, secretary, America, ca. 2010. Walnut, oak, ebony, and maple with tulip poplar, white pine, and maple; metal, glass, muslin, silk, bone, horn, and abalone. H. 95 1/2", W. 42 1/4", D. 19 3/4". (Courtesy, Chipstone Foundation, gift of Penny and Allan Katz; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Composite image showing a corner of Harold Gordon’s dining room with the secretary before and after alteration, Templeton, Massachusetts, ca. 2005. (Courtesy, Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art.) These low resolution images were the pictures of record that broke this story.

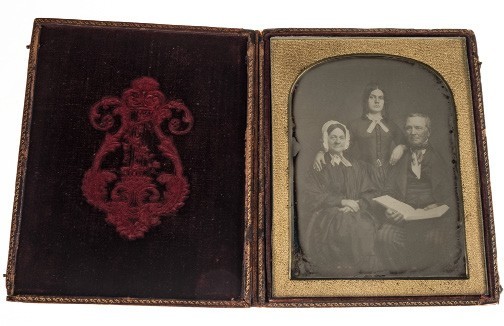

Portrait of unidentified sitters, America, ca. 1845. Daguerreotype and case. Case: 5 7/8" x 4 7/8" x 3/4" (closed); 5 7/8" x 9 3/4" x 3/8" (open). Harold Gordon claimed this daguerreotype was a portrait of the Bingham brothers’ grandparents.

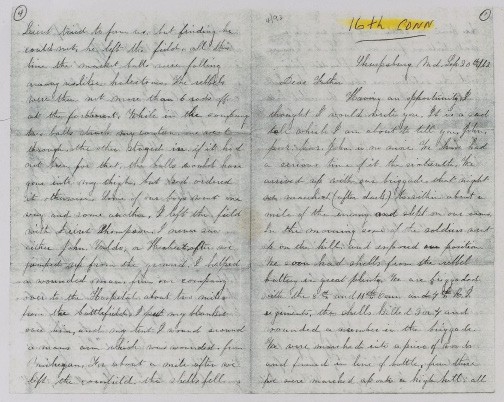

Photocopy of the first and fourth pages of the letter purportedly written by Wells A. Bingham to his father, September 20, 1862. (Courtesy, Antietam Battlefield Library Vertical Files.)

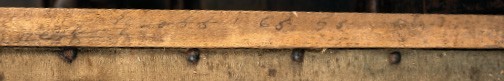

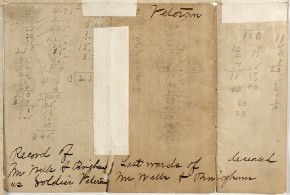

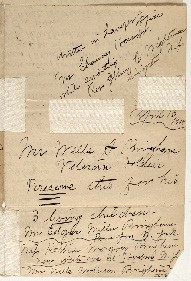

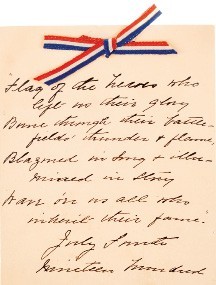

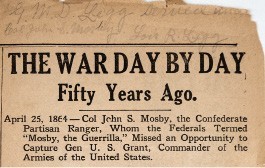

Comparisons of handwriting by Harold Gordon and Wells Bingham

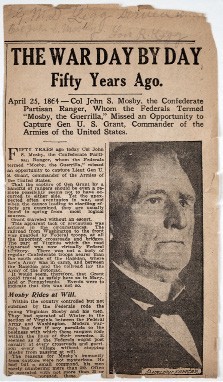

with inscriptions on the secretary and accompanying documents: 1. Numbers written in pencil on side of desk slide; 2. Numbers on verso of the Personal War Sketch; 3. Phrases on verso of the Personal War Sketch; 4. Note in the secretary with red, white, and blue ribbon; 5. Notations on top of “the war day by day” article.

Comparisons of handwriting by Harold Gordon and Wells Bingham

with inscriptions on the secretary and accompanying documents: 1. Numbers written in pencil on side of desk slide; 2. Numbers on verso of the Personal War Sketch; 3. Phrases on verso of the Personal War Sketch; 4. Note in the secretary with red, white, and blue ribbon; 5. Notations on top of “the war day by day” article.

Comparisons of handwriting by Harold Gordon and Wells Bingham

with inscriptions on the secretary and accompanying documents: 1. Numbers written in pencil on side of desk slide; 2. Numbers on verso of the Personal War Sketch; 3. Phrases on verso of the Personal War Sketch; 4. Note in the secretary with red, white, and blue ribbon; 5. Notations on top of “the war day by day” article.

Comparisons of handwriting by Harold Gordon and Wells Bingham

with inscriptions on the secretary and accompanying documents: 1. Numbers written in pencil on side of desk slide; 2. Numbers on verso of the Personal War Sketch; 3. Phrases on verso of the Personal War Sketch; 4. Note in the secretary with red, white, and blue ribbon; 5. Notations on top of “the war day by day” article.

Comparisons of handwriting by Harold Gordon and Wells Bingham

with inscriptions on the secretary and accompanying documents: 1. Numbers written in pencil on side of desk slide; 2. Numbers on verso of the Personal War Sketch; 3. Phrases on verso of the Personal War Sketch; 4. Note in the secretary with red, white, and blue ribbon; 5. Notations on top of “the war day by day” article.

Harold Gordon, Wells A. Bingham Personal War Sketch, ca. 2010. Ink on paper. (Courtesy, Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art.) Beginning in the late 1890s, GAR post officers began to distribute personal war sketch questionnaire forms at their annual reunions so that aging veterans could record their memories. No authenticated examples of GAR questionnaires completed in lawyers’ offices are known.

Verso of the Personal War Sketch illustrated in fig. 5.

Article reporting Wells Bingham’s suicide, New York Times, August 17, 1904, with notes by Harold Gordon. (Courtesy, Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art.) W. A. Bingham and Co. filed for bankruptcy on September 4, just a few weeks after Wells Bingham’s death. His suicide on August 16 was close to the anniversary of his enlistment and the Battle of Antietam.

Envelope for Wells A. Bingham’s paper company, America, ca. 1900.

Typed note with Harold Gordon’s falsified Edgar M. Bingham signature pasted inside the center drawer of the secretary illustrated in fig. 1.

One of the newspaper clippings found inside the secretary illustrated in fig. 1.

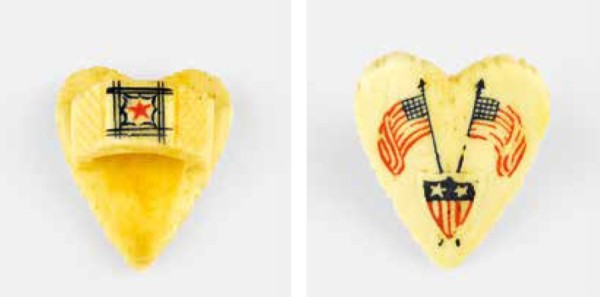

Membership Badge to the Lafayette Post 140, New York Grand Army of the Republic, 1901. Silver and metal.

Detail showing the dedicatory plaque on the secretary illustrated in fig. 1. Bone.

E. B. and E. C. Kellogg and George Whiting, The Eagle’s Nest. “THE UNION! IT MUST AND SHALL BE PRESERVED,” Hartford and New York, 1861. Hand-colored lithograph on paper. (Courtesy, Library of Congress.) “The Union Must and Shall Be Preserved” was also the title of a pro-Union song written in 1860 and set to the tune of “Star Spangled Banner.”

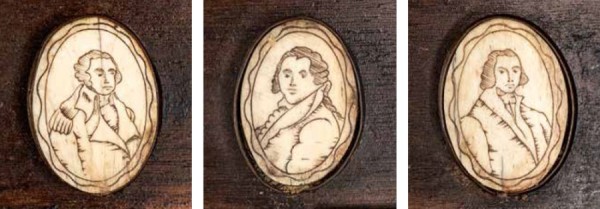

Composite illustration showing the portraits of Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, Abraham Lincoln, George Washington, Alexander Hamilton, and an unidentified individual, inlaid in bone on the secretary illustrated in fig. 1.

Composite illustration showing the portraits of Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, Abraham Lincoln, George Washington, Alexander Hamilton, and an unidentified individual, inlaid in bone on the secretary illustrated in fig. 1.

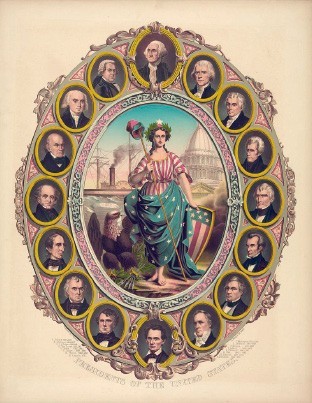

Presidents of the United States, Philadelphia, 1861. Lithograph on paper. 21" x 27". (Courtesy, Seth Kaller, Inc.) Augustus Feusier produced the lithograph and Francis Bouclet published the image.

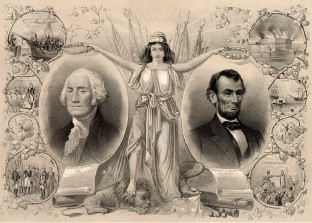

Kimmel and Forster, Columbia’s Noblest Sons, New York, 1865. Lithograph on paper. 16" x 20". (Courtesy, Library of Congress.)

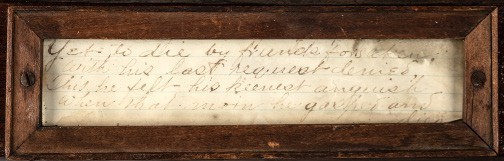

Note with lyrics from the song “The Little Major” by Henry Work, written and composed in 1863.

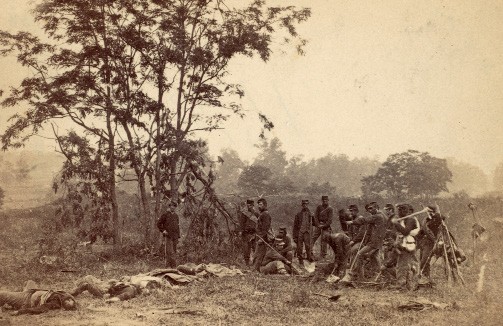

Alexander Gardner, Burying the Dead on the Battlefield of Antietam, September 1862. Albumen silver print from glass negative. 2 13/16" x 3 15/16". (Courtesy, Metropolitan Museum of Art.) In this image from Gardner’s series The Dead of Antietam, a Union burial detail prepares to inter Federal dead killed in the cornfields of David Miller’s farm.

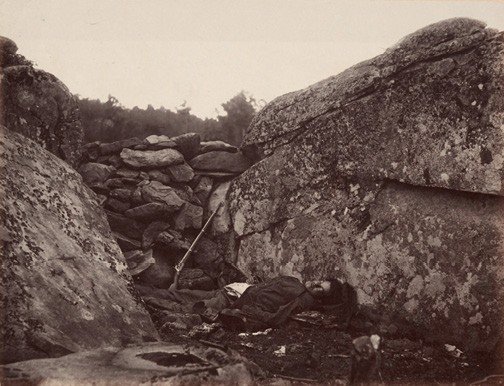

Alexander Gardner, Home of a Rebel Sharpshooter, Gettysburg, from Gardner’s Photographic Sketchbook of the War, 1865. Albumen silver print. 6 13/16" x 8 13/16". (Courtesy, Museum of Modern Art.) The photograph represents the tragic aftermath of the Battle of Gettysburg by focusing on a single dead soldier lying inside what Gardner called a “sharpshooter’s den.” Later analysis revealed that he had staged the image to intensify its emotional effect. Gardner moved the soldier’s corpse, propped up his head so that it faced the camera, and placed his own rifle next to the body.

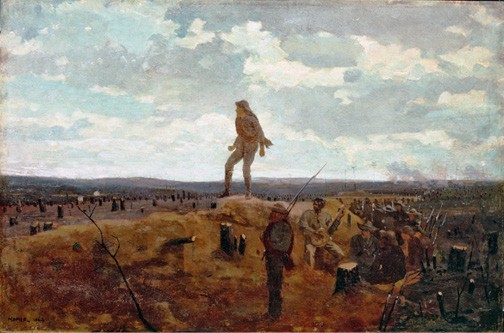

Peter Frederick Rothermel, The Battle of Gettysburg, America, 1870. Oil on canvas. 16' x 32'. (Courtesy of the State Museum of Pennsylvania, Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission.) The Public Ledger, a Philadelphia newspaper, was shown the painting before the opening: “In conception and execution it well deserves the praise it has largely received from competent art critics, at perhaps being the best as well as the largest war picture on this side of the Atlantic.”

Winslow Homer, Defiance: Inviting a Shot Before Gettysburg, America, 1864. Oil on panel. 12" x 18" (unframed). (Courtesy, Detroit Institute of Art.) Winslow Homer served as a war correspondent for Harper’s Weekly magazine during the Civil War. Over the winter of 1864–1865, he traveled to Petersburg, Virginia, to sketch the Union siege of the city. Here, a young Confederate soldier taunts the opposing force. Having endured months of trench warfare, the soldier stands defiantly and challenges the distant Union sharpshooters to fire at him.

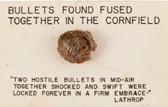

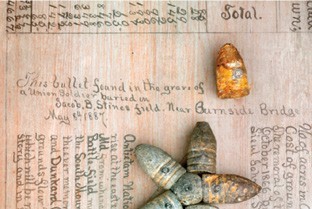

Bullets found fused together at Antietam, Washington County, Maryland, 1862. (Courtesy, Heritage Auctions.)

Brady and Company, Relics of Andersonville Prison, America, June 1866. Albumen silver print from glass negative. 8 11/16" x 7 7/16". (Courtesy, Metropolitan Museum of Art.) To support her effort for proper burial of the Andersonville dead, and to raise money for veteran relief in general, Clara Barton displayed and sold souvenirs of Andersonville. The largest item for sale was a portion of the infamous Dead Line, a wooden fence that prisoners were prohibited from crossing on pain of death.

John Philomen Smith, Shadowbox of Antietam Relics, America, 1886. Wood, pencil, paint, metal, fabric, found objects. H. 39", W. 34", D. 5". (Courtesy, Maryland Historical Society.) John Philemon Smith was seventeen years old when he witnessed the Battle of Antietam. He spent the rest of his life as a teacher and historian of that single day of battle. The text inside the box records the dedication of the Antietam National Cemetery in 1867 and includes a list of the Union soldiers who died at Antietam. The centerpiece is a miniature replica of the Private Soldier Monument, installed at the cemetery in 1880.

Detail of the Shadowbox of Antietam Relics illustrated in fig. 25.

Detail of the fraudulent battle flag remnant mounted in a tin can on the secretary illustrated in fig. 1.

Spoon carved by a 16th Regiment Connecticut Volunteer infantryman, America, May and September 1864. Diffuse porous hardwood. L. 5". (Courtesy, Cowan Auctions.) The spoon is carved with branching leaves, a shield with eagle’s head, an inscription reading “Sumter Prison” around end, “Higgins | Waldo | Dowd | Macinnes | Whitney | Duane | Prisoners | Of | War” on one side and “Qui Trans Sus” on the underside near the end. Near the bowl on the underside is another inscription reading “Captured | April 20th | 1864.” The underside of the bowl has a carved five-pointed star.

James H. Gagan, signet ring, America, 1864. Bone and ink. (Courtesy, American Civil War Museum.) Gagan, a Union officer, carved this ring from a bone while he was imprisoned at Libby Prison, Richmond, Virginia.

Detail showing the use of abalone on the secretary illustrated in fig. 1

Lieutenant Robert Smith, necklace, Johnson’s Island, Ohio, 1864. Hard rubber and shell. (Courtesy, Heidelberg University.) Robert Smith was one of the more skilled and prolific whittlers of the Confederates imprisoned at Johnson’s Island. Men at Johnson’s Island most often worked in hard rubber but often augmented it with abalone shells found on the island’s shore. Friends and descendants of Johnsons Island Cival War Prison.

Stereoview photograph showing the Memorial Day observance at Civil War Soldiers’ Monument in Paris, Maine, May 30, 1876. (Courtesy, Maine Historical Society.) For Memorial Day observances, including the speech-making captured in this photograph, the obelisk has been draped in wreaths, garlands, and American flags, activities often organized by widows’ memorial organizations.

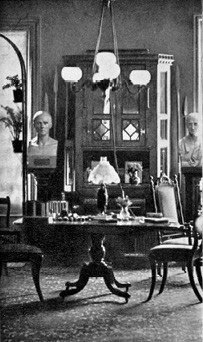

Library at 113 Boylston St., showing the “Memorial Cabinet” and the busts of La Place and Nathaniel Bowditch, in Vincent Yardley Bowditch, Life and Correspondence of Henry Ingersoll Bowditch, 2 vols. (Boston: Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1902), 2: 28. (Courtesy, Archive.org.) Standing against a wall behind a library table and chairs, the cabinet is tall, with crenulated molding at the top and glazed doors on three sides. A pitcher of flowers rests on it, seemingly in front of framed photographs. The Bowditches were an elite Boston family; Gordon invented a “folk” version of this cabinet to reflect the Bingham family’s lower-class status.

THE CIVIL WAR LINGERS just below the surface of contemporary life in the United States, its bloody lessons visible in commemorative landscapes, political discourse, and popular culture. America’s lasting memory and the war’s continued impact become particularly visible during commemorative anniversaries, and the recent 150th anniversary was no exception. Approaches to remembering the Civil War during 2011–2015 were, however, a study in marked contrasts. In popular culture, the sesquicentennial was a generative time. Steven Spielberg’s Oscar-winning Lincoln, released in 2012, dramatized Lincoln’s fight to ratify the 13th Amendment in the last months of both the war and his life. That same year the major traveling loan exhibition The Civil War and American Art, the brainchild of the Smithsonian American Art Museum’s senior curator Eleanor Jones Harvey, won praise for the way it “threw off the bonds of literalism” and argued that Americans represented the scars of the Civil War metaphorically—in landscape and in genre paintings—rather than battlefield history paintings. In 2014 The Atlantic published Ta-Nehisi Coates’s landmark article “The Case for Reparations,” arguably the most influential piece of writing in this century to consider the legacy of the Civil War and Reconstruction. Yet historians who have remained invested in a model of commemoration based on battlefields, soldiers, and military history exemplified by the war’s centennial in the 1960s viewed the sesquicentennial as “disappointing” and “anemic,” with an overemphasis on cultural context over battle. As one leading historian wrote, “There’s a conscious effort to shift away from military issues . . . . The fact of the matter is that emancipation was not about to happen without war.” Sales of Civil War militaria also were unremarkable, and while battlefield tourism increased, it remained far below visitor rates of 1961–1965. By emphasizing histories of slavery, emancipation, and national trauma writ large, this era of the sesquicentennial revealed a nostalgia for the traditional centering of soldiering.[1]

In the final year of the sesquicentennial, amid what some saw as the abandonment of the Civil War soldiers in national memory, the “Bingham Secretary” emerged (fig. 1). This “folk art” object came to widespread public attention on January 23, 2015, the opening night of the Winter Antiques Show in New York City. An undisputed highlight, the secretary was exhibited by Americana dealer Allan Katz. As his essay for the show reported, the secretary was presented to 16th Regiment Connecticut Volunteer Infantry veteran Wells Bingham on July 4, 1876, in Hartford, Connecticut, “by a group of Wells Bingham’s friends in remembrance of his brother John, killed at the battle of Antietam on September 17, 1862.” Wells had survived the bloodiest single-day battle in American history, but his brother John was killed on the battlefield. The secretary was “a special gift in memory of his dead brother,” while “also made in part as a celebration that the Union was indeed preserved and that America was celebrating its 100th birthday.” The carved stars, fans, pendants, Latin phrases, and statements conveying ownership and provenance made the secretary an absorptive, multisensory memory object that typified the vernacular eclecticism of the post-war decades.[2]

The Bingham secretary quickly achieved something rare in the Americana market, striking a chord with both Civil War buffs and mainstream arts journalism. Upon first seeing the object in 2011, John Banks, author of Connecticut Yankees at Antietam, was moved to write about the secretary and its story on his blog. The charismatic memorial object was also featured in the New York Times report on the Winter Antiques Show, and most unusually, singled out for a story in Hyperallergic. Expressing what had drawn so many to the object, the author wrote that the secretary “is something of an anomaly,” a quality she attributed to the fact that “such elaborate mourning rituals and objects had prevailed during the Victorian age but were mostly dropped in the face of the overwhelming death counts of the U.S. Civil War.”[3]

As the Hyperallergic article suggested, key to the Bingham secretary’s enthusiastic reception was its perceived eloquence about the psychological trauma of Civil War soldiers, a topic that had emerged in scholarly literature in the 1990s and gained momentum during the sesquicentennial. This trajectory reflected the rise of trauma studies more broadly. Perhaps the best explanation of how the object’s history of trauma fueled its star quality came from Antiques months later, after the piece had been acquired by the Wadsworth Atheneum. The Wadsworth has deep historic connections to the Union cause through the Colt family, whose foundational gifts to that institution already included Civil War-related objects. As Wadsworth curator Alyce Perry Englund wrote, the secretary expanded “the museum’s ability to present more intimate narratives on the Civil War and Reconstruction while distinguishing art-making as a means of negotiating traumatic experiences by those who endured the conflict.” It was as if the secretary had overturned Walt Whitman’s observation that “the real war would never get in the books,” a statement that has long stood for the inadequacy of institutionalized history to tell Civil War experiences. Here was an object exceptionally expressive of the “real war,” with aesthetics, credentials, and sheer presence enough to make it the jewel in the crown of a storied American art collection. Yet viewed through the lens of this article, the Bingham secretary offers proof of Whitman’s observation.[4]

Famously, the Bingham secretary proved to be a forgery carried out by antiques dealer Harold Gordon, who had sold the piece to Katz. In 2016 a credible source within the Americana community contacted the Wadsworth Atheneum to express doubts about that object’s authenticity and forwarded a digital image of the secretary before it was embellished. In response, the museum’s curatorial and conservation staff launched an internal investigation, which included a technical examination of the object and a reassessment of the accompanying documents. While this was underway, Maine Antique Digest editor Clayton Pennington published conclusive evidence that the secretary was fraudulent in an article titled “Fake Civil War Masterpiece: A Tale of Two Photographs.” One photograph showed the secretary in its original form, whereas the other showed the piece as it appears today (fig. 2); significantly, both photographs were taken in the same room in Gordon’s house. Pennington also secured a confession from Gordon and noted that in his article.[5]

Gordon buttressed his fake with a large selection of period ephemera and a compelling, albeit contrived, story based in historical fact. Using memorabilia, family photographs, letters, and military records, he manipulated scholars, curators, dealers, and buyers into focusing on the “history” of his fake at the expense of the physical evidence. The secretary captivated a niche audience still fascinated by Civil War soldiers’ experiences and appealed to broader audiences primed by recent books, exhibitions, and popular culture to connect more with Civil War memory and trauma than with heroism.[6]

A Doctored Story

When the Wadsworth Atheneum purchased the secretary, the museum also received additional memorabilia and a binder containing Gordon’s musings, correspondence, and research. Among these ancillary materials is a daguerreotype of “Bingham grandparents” now known to be unrelated to the family (fig. 3), printed ephemera, the book History of Battle-Flag Day, September 17, 1879, and “several miscellaneous badges and accoutrements” assembled by the forger over approximately a decade.

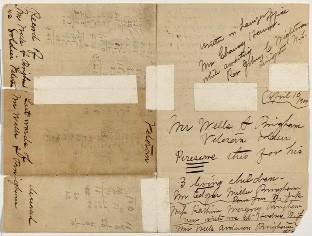

The documents provided by Gordon consist of poorly printed images on copy paper, some stained and rumpled and others littered with his handwritten notes, exploratory thoughts, musings on the secretary desk’s insignia, and mathematical calculations for dates significant to his fictitious narrative. To make his story more convincing, Gordon also included information pertaining to the Bingham family along with his correspondence with historians. Most crucial to the forger’s narrative were a transcription of a letter about the Battle of Antietam from Wells Bingham to his father, Elisha, dated September 20, 1862; a Personal War Sketch form of the type distributed by Grand Army of the Republic posts in the 1890s; and a New York Times article about Bingham’s death in 1904.[7]

The Antietam letter (fig. 4) came to Gordon by way of author and Civil War historian John Banks, with whom Gordon first began corresponding about the secretary in 2011. One of several experts the forger maneuvered to enhance the secretary’s reputation, Banks visited Gordon at his home in 2011 “to talk about the Civil War and one of his recent purchases: A Victorian-era secretary with a direct tie to the Battle of Antietam.” Spurred on by this object and the tragic story of the Bingham brothers, Banks traveled to the Antietam Battlefield National Archive and Library, where he found a color photocopy and typescript of Bingham’s letter to his father. It was, the historian noted, “the first letter I saw in a stack of transcripts and other copies of letters from Connecticut soldiers about Antietam.”[8]

In the correspondence, sixteen-year-old Wells Bingham recounts the horrors of the Battle of Antietam and the death of his brother John. Written from Sharpsburg, Maryland, three days after the battle, the letter begins “Having an opportunity I thought I would write you. It is a sad tale which I am about to tell you, John, poor John, is no more.” From there, the seven-page letter recounts in great detail the battle, the 16th Connecticut’s role within it, and the fate of John. He was shot in the “left breast” and, although Wells chose not to see his brother’s lifeless body, he learned that John had been stripped of all his belongings by the “rebbels” and buried in a grave with the forty other men from the 16th who had died in the battle. The location of Wells’s original letter is not known, nor does the Antietam Battlefield National Archive and Library know from whom or when they received the color photocopy and typescript. Wells’s account was accepted at the time of the secretary’s appearance on the market, and until the original document is located, its authenticity cannot be verified.[9]

The Personal War Sketch purported to be by Wells A. Bingham has answers to the questionnaire on the front and inscriptions referring to the conditions under which Wells completed the form on the back (fig. 5):

Written in Lawyer’s | office | Mr. Cheney [. . .] | while awaiting | Rev John C Wightman | Livingston N.J. | April 13, 1904 | Mr Wells A Bingham | Veterern [sic] Soldier | Preserve this for his | 3 living children— | Mr Edgar Miller Bingham | Penn Yan N. York | Miss Katherine Mergovy Bingham | now with me at Hudson N. Jer | Mr Wells Anderson Bingham | at [. . .] (figs. 6–7).

The last phrase “Last words of Mr Wells A Bingham” suggests, rightly or wrongly, that the veteran had been preoccupied with memories of the war during the last year of his life.[10]

Written in a hand that does not match Wells Bingham’s, the Personal War Sketch is problematic because documents of this type were not typically completed in lawyers’ offices or intended for personal use. Moreover, much of the wording parallels that in 16th Connecticut Regiment Second Lieutenant Barnard Blakeslee’s 1889 published account. Bingham’s sketch offers information and firsthand accounts of the veteran’s service. Born on August 7, 1846, in East Haddam, Connecticut, Bingham enlisted in Company H, 16th Regiment, Connecticut Volunteer Infantry, on his sixteenth birthday. Besides Antietam, the sketch mentions engagements in other famous battles—Fredericksburg, the Siege of Suffolk, and the Blackberry Raid. Like Blakeslee, Wells recalled being present “when Burnside was relieved of command of Army of the Potomac.” Special mention was made of the unfortunate day in April 1864 when the 16th Regiment Connecticut Volunteer Infantry was captured in Plymouth, North Carolina, and subsequently imprisoned at the POW camp in Andersonville, Georgia. The sketch also notes that just a month before the capture of his comrades, Wells and four noncommissioned officers were sent to New Haven, Connecticut, “on recruiting service” and expresses joy that he had escaped his company’s calamitous fate. To the question, “Give the names of a few of your most intimate comrades in the service,” the sketch lists three members of the 16th Regiment, Connecticut Volunteer Infantry—Lieutenant Ariel J. Case, Hartford; Corporal Gilbert W. Thomson, Bristol; and Sergeant Edgar C. Wheeler, Manchester—all of whom also avoided imprisonment at Andersonville. Gordon claimed that the secretary was given to Wells Bingham “by a group of John’s [John Bingham’s] friends. “It is not known who these individuals were except for his close friend Sargent Edgar C. Wheeler.” The forger used the relationship between Sergeant Wheeler and Wells Bingham to link the secretary to veterans’ remembrances and create a false provenance.[11]

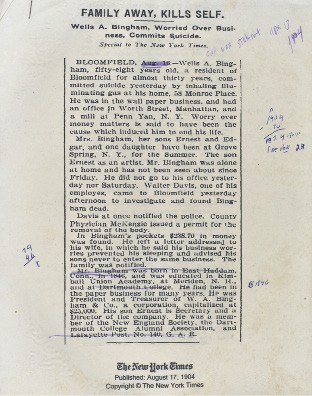

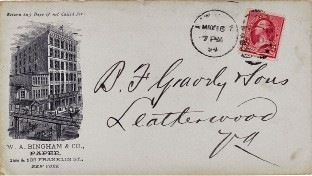

The 1904 date for the GAR form tied Bingham’s war record back into the last, tragic months of his life. This connection is not supported in the third document Gordon included with the sale of the secretary: an annotated and highlighted photocopy of the New York Times article about Wells A. Bingham’s death by suicide on August 16, 1904, which is the only authenticated document among the three (fig. 8). After the war, Bingham became a successful businessman and established W. C. Bingham and Company, a paper manufacturing and distribution firm headquartered in New York City (fig. 9). In 1900 a massive factory fire put the company in financial distress. Bingham subsequently wrote to his family expressing his despair and, as his obituary reveals, committed suicide by gas inhalation.[12]

Death by suicide is complex and deeply personal, and no authenticated period documentation survives to identify Bingham’s motivations other than the Times article. If Wells remained haunted by his service, he would not have been alone. Although the precise number is unknown, many Civil War veterans struggled with suicidal ideations, although this phenomenon is better documented among those who were hospitalized for “insanity.” The essay produced for the secretary’s offering at the Winter Antiques Show ends with information about Bingham’s suicide but does not mention his business struggles, leaving those captivated by the object and its story to conclude that the veteran’s death was related to his war service.[13]

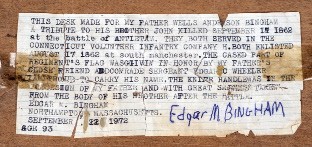

Gordon’s doctored story included a fictitious provenance wherein the secretary descended from Wells Bingham to his grandson. Pasted within a drawer is a fabricated typewritten letter dated September 22, 1972, onto which Gordon, faking the shaky hand of a ninety-three-year-old, added the name of Wells’s son Edgar M. Bingham (1879–1973) (fig. 10). This spurious document—aged, tattered along the edges, and stained—created a false provenance that extended from the Civil War era to the twentieth century with links to the American centennial. Attempting to further connect “period” documentary evidence to the fabricated object, Gordon gilded the lily with the statement: “THE CASED PART OF THE FLAGWASGIVIN IN HONOR BY MY FATHER’S CLOSE FREIND ANDCOMRADE SERGEANT EDGAR C WHEELER. I AM PROUD TO CARRY HIS NAME.” Gordon’s misspellings and typing errors contributed to the letter’s appearance of authenticity.[14]

Gordon attempted to legitimize these core documents by engaging Civil War historians and enthusiasts in correspondence that he added to the “historical” documentation accompanying the secretary. In addition to John Banks, the faker also exploited the generosity and expertise of Dr. Leslie Gordon, a historian and author of A Broken Regiment: The 16th Connecticut’s Civil War, as well as Eric Connery and Bill Caughman, who allowed Gordon to compare the 16th Regiment's recontructed 1889 flag in the Connecticut State Capitol Building with the remnant the faker inserted into the secretary. Gordon’s correspondence with these scholars enabled him to create a paper trail of inquiry that feigned genuine historical research. With his falsified documents and a fraudulent secretary, Gordon misappropriated the true narrative of Wells Bingham’s life as well as that of his brother.[15]

A Doctored Object

Gordon’s reliance on documents to establish a convincing story continued into the design of the Bingham secretary itself. At the time of its appearance on the market, many observers noted the numerous items of ephemera tucked within its drawers and the profusion of inscriptions, which range from clear to enigmatic. Featuring a plethora of textual embellishments, the object itself became a readable manuscript that told its own story with a calculated combination of precision and ambiguity. The secretary’s exuberant decoration delivered patriotic messages that seemed to reveal fervent expressions of surviving veterans honoring their own and a healing nation celebrating its 100th birthday. Hewing close to a narrow range of patriotic Civil War era history and visual culture, the details of the desk offered an enticing example of individuals preoccupied with personal and national histories, an angle of interpretation certain to fascinate the historically minded Americana and art museum spheres.

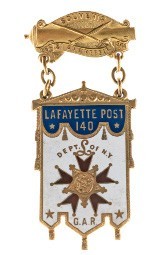

Within the glazed doors of the secretary desk, Gordon mounted a handwritten poem of the era along with three nineteenth-century newspaper clippings regarding actions of Connecticut’s 16th Regiment at Antietam and the legend of their battle flag (fig. 11). Additional undated clippings recount a Civil War veterans’ reunion in Middletown, New York, and Confederate Colonel John S. Mosby’s failed opportunity to capture General U. S. Grant. In the drawers, Gordon also placed memorabilia. A silver souvenir coin “presented by B. F. Blakeslee to W. A. Bingham as a remembrance” established a personal connection between Wells Bingham and the 16th Connecticut Regiment’s leading nineteenth-century historian, and a membership badge to the Lafayette Post 140, New York Grand Army of the Republic, corroborated biographical details recorded in Wells Bingham’s New York Times obituary (fig. 12). These period newspaper clippings and memorabilia contributed greatly to perceptions of authenticity, as did the writing and other markings in the secretary.

Other inscriptions on bone ornament reference the American Revolution and the Civil War, events viewed through the lens of historical parallelism by both the North and South. Familiar Latin mottos from the United States seal—“E PLURIBUS UNUM” and “ANNUIT COEPTIS”—are wrapped around the front and sides of the secretary. Strangely, “IN VINDICIAM LIBERTATIS,” a third, relatively obscure Latin motto meaning “in defense of liberty,” which was sourced from William Barton’s rejected proposal for the United States seal, also appears across the bottom of the secretary. These mottos triangulate references to the Revolutionary and Civil War eras and the centennial.[16]

In his “research,” Gordon diagrammed and translated every Latin expression, often giving the false impression that he struggled to correctly decipher their meaning. Noting “possibly, to research,” he translated “IN VINDICIAM LIBERATIS” as “citizen authority” rather than “invincible freedom,” and “ANNUIT COEPTIS” as “he has approved our beginnings” instead of “God has favored us.” This gave scholars an opportunity to correct Gordon’s work, thus making the secretary and its contrived history seem like more of a discovery.[17]

The upper door rails are embellished with the name “John F. Bingham” and the designation “H. CO. 16th C.V.I.,” the regiment and company of both Binghams, and the plaque at the center of the secretary bears the inscription:

Presented to Wells A. Bingham by his friends This secretary a remembrance of his brother John F. Bingham who offered up his life at Antietam, Maryland. Sept. 17, 1862. The encased silk is a remnant of the colors carried that day by the infantry. This memory plaque made from a shard of his knife. July 4, 1876 (fig. 13).

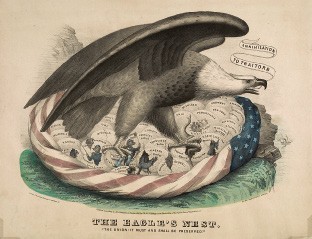

Gordon borrowed the concept of a commemorative plaque from Civil War monuments, which typically included explanatory dedications for posterity and dates, often coinciding with public holidays related to the war. For example, the Soldiers Monument in Seaside Park, Bridgeport, which has the same date as the Bingham secretary’s plaque, bears the inscription: “Dedicated to the memory of the Heroic men of Bridgeport, who fell in the late war for the Preservation of the Union. July, 1876.” On the secretary, Gordon used dedicatory language derived from that found on public memorials to present a readily comprehensible narrative to interested audiences. Similarly, his phrase “THE UNION PRESERVED,” which appears below the clock face, repeats patriotic messages from public Civil War visual culture, including the lithograph The Eagle’s Nest. The Union! It must and shall be preserved, printed in Hartford and New York City in 1861 (fig. 14).

The secretary’s numerical symbolism, imagery, and dates were designed to be “read” for symbolic significance, and their interpretation became, like the rest of the fake, inseparable from the “research” compiled by Gordon. In his object assessment, the forger asserted his interpretation of other decorative elements, connecting each to the Bingham family, the Civil War, America’s centennial, and the history of the 16th Connecticut. He postulated that the chain and sixteen gold-painted wooden balls “may represent the 16th infantry” and that the eight spires atop the object symbolized the six Bingham brothers and stepbrothers who fought in the Civil War.

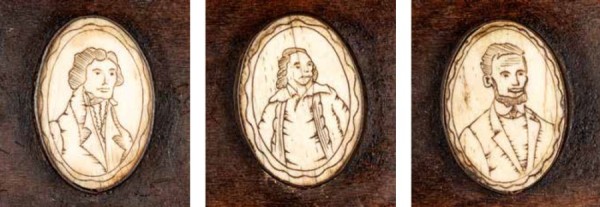

Six portraits inscribed on small, oval bone plaques above the top drawer further the secretary’s visual program of historical parallelism between the founding of the United States and its bloody reunification in 1865 (fig. 15). Providing a hint of uncertainty to enhance the sense of authenticity, Gordon catalogued these carvings as “six engraved oval plaques of well-known Americans . . . Lincoln, Washington, Jefferson, and Franklin. The other two I am unsure of.” The inclusion of non-presidents Franklin and, as it was later concluded, Hamilton, is anomalous in contemporary visual culture, but Abraham Lincoln paired with founding presidents is found frequently in United States and Union print culture. Examples include the 1861 chromolithograph featuring oval portrait medallions of all the presidents made to celebrate Lincoln’s inauguration and the 1865 lithograph Columbia’s Noblest Sons, made to commemorate his assassination (figs. 16–17). This latter image, which features bust portraits of Washington and Lincoln surrounded by vignettes of major events in the Revolutionary and Civil Wars, also includes representations of the Declaration of Independence and the Emancipation Proclamation, another common historical parallel of the Civil War era. Not surprisingly Gordon, in his fusing of text and language from the Revolutionary and Civil War eras, left out any references to emancipation.[18]

In hindsight, the Bingham secretary emerges as a forgery legitimized by carefully coordinated written and iconographic references. Avoiding altogether any references to emancipation—a prevalent theme throughout the visual cultures honoring the Union side of the Civil War—Gordon instead built the object’s credentials through the American Revolution, which, whether purposefully or not, mimicked the very strategy used by both the North and South to legitimize the Civil War. This engagement with national events and public discourse that center white histories of the Civil War was undergirded by a design strategy that exploited the more intimate—and to the modern eye, “relevant”—history of the Binghams and the 16th Regiment Connecticut Volunteer Infantry.

Doctored Trauma

The many visual and textual references to historical events legitimized the Bingham secretary to Americana and antiques audiences as well as to the interested public, but they do not explain why the secretary struck a chord with the sesquicentennial audiences. Alongside its antiquarian credentials was a distinctive timeliness; the fake appeared in the last year of the sesquicentennial. But Gordon’s deceptive documentation and augmentation of the secretary also possessed a conceptual timeliness calibrated to appeal to a modern interest in the psychological experiences of warfare. It presented what Antiques magazine would call an “intimate narrative” that distinguished “art-making as a means of negotiating traumatic experiences by those who endured the conflict.” This observation reflects how the art market translated the forger’s work to exploit or view the object through the lens of the modern rise of trauma studies and its growing importance for modern interpretations of the lives and experiences of Civil War soldiers. Gordon inspired such interpretation through the materials he selected to ornament the secretary; those alluded to or quite literally claimed to be traces of suffering experienced by the Bingham brothers and the 16th Connecticut more broadly. Comparing Gordon’s disingenuous strategies with several lesser-known but powerful works that truly grappled with the death of soldiers demonstrates how Gordon made an object with immense appeal to art museums and, in doing so, strayed from the very qualities that make real Civil War memory objects most meaningful.[19]

A number of carefully researched published histories convey the undoctored and harrowing story of the 16th Connecticut, including Company H, in which John and Wells Bingham served. The Bingham brothers were mustered into Company H with their stepbrothers on August 24, 1862. Just two weeks later, this “green” regiment of nearly 475 men marched onto the battlefield of Antietam. Amid the hail of five hundred cannons firing three thousand rounds hourly, 22,717 Union and Confederate soldiers were dead, wounded, or missing by the end of the twelve-hour-long battle. John Bingham was killed early in the afternoon, when Company H was rushed by veteran South Carolina and North Carolina troops.[20]

After surviving this initial assault, seventeen-year-old Wells likely experienced further horrors. The 16th found itself with several other regiments in a twenty-four-acre cornfield that would become known as the Bloody Cornfield. There, a wave of bullets suddenly whizzed through the ranks. As Private Robert Kellogg recalled, it was “one of the most terrific volleys of musketry that I think was ever poured into a Regt.” “Our men,” he wrote, “fell on every side.” The line officers were just as green and confused as the privates. One officer cried out in desperation, “Tell us what you want us to do and we’ll try to obey you.” The tall, uneven corn stalks compounded the chaos; men could only see a small portion of their line at a time. By the end of Antietam, most of the regiment’s ranks were dead, wounded, or absent from the field. The toll was also, as we would describe it today, psychological. Fellow Connecticut 16th infantryman George N. Lamphere would write, “The fact is well known to all soldiers that one of the most trying positions troops can be put into is to be lying around inactive and yet be under fire. It requires courage and it is a great consumer of nerve power.”[21]

Regimental casualties were again high at the Battle of Fredericksburg, Virginia, in December of 1862. Bad luck followed into the spring of 1864, when the regiment was garrisoned in Plymouth, North Carolina. Besieged by the Confederates on April 17 and outnumbered five to one, the regiment surrendered and became prisoners of war, most of whom were imprisoned at Andersonville, Georgia, until the war’s end in April of 1865. Of the more than forty thousand Union soldiers imprisoned at Andersonville, thirteen thousand died of starvation and disease. Wells Bingham, along with most of Company H, was not at Plymouth and thus was spared capture. But the fate of the 16th lent an added aura of tragedy to the secretary, especially because it was understood to have been a gift from at least one fellow veteran of the 16th Connecticut: Sergeant Edgar Wheeler. Gordon invented a documentary record of Wells’s anguish by adhering to the secretary a handwritten note “Yet to die by friends forsaken, with his last request denied, This he felt his keenest anguish, when that morn he gasped and died,” the last verse of the Civil War song “The Little Major,” by Henry Work (fig. 18). These details led to conclusions articulated first by Katz and then by the Wadsworth Atheneum, which would ultimately argue that central to the secretary’s value was its “rich and relevant narratives, such as the Bingham brothers’ experiences during the war and Wells Bingham’s struggle with post-traumatic stress disorder.”[22]

This avenue of interpretation reflected a growing interest in analyzing Civil War soldiers’ experiences through the lens of post-traumatic stress (PTSD), a mental disorder first recognized by the American Psychiatric Association (APA) in 1980. PTSD is not restricted to warfare, but its emergence as a medical diagnosis was presaged during the world wars with terms like “shell shock” and “mental neurosis.” The modern diagnosis emerged in the United States in the wake of the Vietnam War, a conflict of which Harold Gordon was a veteran. Psychological trauma, as it is conceptualized by the APA, is damage to a person’s mind as a result of one or more events that cause “overwhelming amounts of stress that exceed a person’s ability to cope or integrate the emotions involved.” Exceeding the mind’s ability to process events into memories, “trauma become[s] freeze-framed in an eternal present,” so that disturbing thoughts, feelings, or dreams relating to the trauma remain present or easily triggered.[23]

The concept of trauma and PTSD first began to enter scholarly writing about Civil War history in 1999 with the publication of Eric T. Dean Jr.’s groundbreaking book Shook Over Hell: Post-Traumatic Stress, Vietnam, and the Civil War. Beginning with the explicit analysis of Vietnam soldiers’ and veterans’ depression, PTSD, and suicidal ideations, Dean then analyzed Civil War soldiers’ writings and medical records for similar phenomena, revealing a “stunning portrait of Civil War soldiers and veterans in acute distress.” In Dean’s account, “the blues” mark what we today would call depression, and episodes of “nerves” and “insanity” bear striking similarity to PTSD. In Dean’s book, death by suicide and attempted suicide emerge as an unquantified but significant trend among Civil War soldiers and veterans, with surviving POWs and veterans who suffered from lifelong injuries left particularly vulnerable. Indirectly, this groundbreaking publication made possible new potential interpretations of Wells A. Bingham’s death by suicide.[24]

A second major contribution to the study of physical and mental anguish experienced by Civil War soldiers was Harvard historian Drew Faust’s This Republic of Suffering, a book published in 2008 to academic and popular acclaim. Faust collated an immense array of Civil War battle statistics, individual stories, and historical context to explore how survivors of the war managed on practical and emotional levels to reconcile the unprecedented carnage that they participated in or witnessed. Avoiding modern terminology including “trauma,” Faust instead used period language like “the work of death,” a phrase used by soldiers and their families to describe the duties of soldiers to fight, kill, and die. Among the many afterlives of Dean’s and Faust’s canonical texts was the 2012 traveling exhibition The Civil War and American Art. Curator Eleanor Jones Harvey has cited both authors as shaping her goal of comprehending how the reaction to death was key to understanding the impact of the Civil War on American art.[25]

Civil War literature is full of personal and moving accounts of death and survival akin to the experiences of the Bingham brothers. From the point of view of museums admirably seeking to foreground works of historical art that prompt reexaminations of the legacy of the war, however, Civil War soldiers’ experiences pose difficulties: very few examples of nineteenth-century American art—writ broadly across media—convey the war’s physical and emotional toll in ways well-suited to art museums’ constraints surrounding collections care, gallery design, or aesthetic standards.

Alexander Gardner’s photographic series The Dead of Antietam is an informative example (fig. 19). Arriving two days after the battle, Scottish-born photographer Alexander Gardner set up his stereo wet-plate camera and started taking dozens of images of the body-strewn countryside, documenting fallen soldiers, burial crews, and trench graves. Gardner worked for Mathew Brady, and when he returned to New York City his employer arranged an exhibition of the work. The crowds of visitors who attended the show looked with “terrible fascination” at what are believed to be the first recorded images of war casualties. Death was unfiltered, and a war that had seemed remote to Northerners suddenly became harrowingly intimate. Gardner’s photographs of Antietam created a lasting legacy by establishing a painfully potent visual precedent for the way all wars have since been covered. Images from The Dead at Antietam became some of the most discussed works in both the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s 2013 exhibition Photography and the American Civil War and the National Portrait Gallery’s 2015 show Dark Fields of the Republic, their imagery and message in tune with the zeitgeist of a modern era keenly interested in the emotional and physical toll of the Civil War. Even so, due to their size and light sensitivity Gardner’s photographs are an example of museum objects whose access is relatively restricted to the general public.[26]

Photography historians have also observed how, at Gettysburg, Gardner and fellow photographer Timothy O’Sullivan tried a new approach to photographing the war dead, dragging the body of a Confederate infantryman to a rocky outcropping and posing his body as if he were a sharpshooter (fig. 20). Titling the image “Home of a Rebel Sharpshooter,” the photographers domesticated the war dead through a carefully crafted, and falsified, narrative. The photographers’ manipulation of corpses is one particularly searing anecdote of a crisis of representation brought about by the modernity of the war. Just as soldiers and their caregivers were groping for words to describe the horror of distant artillery attacks and the unprecedented scale of carnage, visual artists were groping for suitable visual languages to represent it. As historian Stephen Conn has observed, artists trained in traditional models of narrative history painting struggled to capture the nature of Civil War battles on canvas, and while major canvases received significant attention in their era—for example Peter Frederick Rothermel’s The Battle of Gettysburg—such paintings are now viewed more as historical curiosities than transcendent or relevant works of art (fig. 21). Conn highlights Winslow Homer as an important exception (fig. 22). Unfortunately for museums, officers’ portraits and battle scenes in the Grand Manner are far more common than a Homer painting.[27]

Another genre of Civil War material culture of great significance to soldiering but historically excluded from art museum galleries devoted to American art is the relic. Rarely considered beautiful, and typically small and humble, such fragments of the past have seldom been strategically collected and exhibited by art museums. One relic associated with Antietam is the pair of bullets said to have collided in thin air amid the dense hail of gunfire (fig. 23). Some of the more famous relics of the 1860s are those collected by Clara Barton at Andersonville, Georgia, including plates, a checkerboard, and a scrap of the “dead line” fence. Images of Barton’s objects were widely disseminated in a photograph taken by Mathew Brady and reproduced as a carte de visite sold to raise funds for the proper burial of Andersonville POWs (fig. 24). This is where Gordon saw an opportunity. Modeling his design approach off authentic Civil War memorial objects that combine texts and relics—for example John Philomen Smith’s Shadowbox of Antietam Relics (figs. 25–26)—he invented poignant relics and embedded them in a work of “folk art” whose scale and visual interest could hold its own in a gallery of American art. For example, there is the “encased silk a remnant of the color carried that day by the infantry” referenced in the dedicatory plaque and said to have been given to Bingham by Edgar Wheeler (fig. 26). Mounted in a biscuit tin above the dedication, it is literally central to the object. This single embellishment received an inordinate amount of Gordon’s effort and attention, and he used his falsified “research” of this relic to stoke interest in the secretary.[28]

It is well known that the 16th Connecticut’s battle flags had a rich history during and after the Civil War. According to period accounts, when the regiment realized it would be captured at the Battle of Plymouth in North Carolina in April 1864, a Union lieutenant colonel tore their regimental colors into pieces to avoid the flag’s capture and distributed them among the men. Many of these Connecticut soldiers protected flag relics during imprisonment at Andersonville, Georgia, and carried them home after the war. The story was revived by veterans of the 16th with great passion in 1879 when Connecticut’s battle flags, assembled at the State Arsenal, were moved to the Hall of Flags at the newly completed grand State Capitol building. Historian Geraldine S. Caughman wrote:

In preparation for Battle Flag Day at the Connecticut Capitol in 1879, a committee was appointed by the 16th CVI veterans . . . . The committee sent a letter to all members asking for their piece of the flag. Not all the pieces were donated and one man was distrustful of the whole process. He claimed the piece of the flag would be safer in his own home! Nevertheless, enough pieces were collected to make up the central device on a new flag.

This anecdote conveys how much the flag relics meant to veterans of the 16th Connecticut, and the reconstituted flag still stands in the State Capitol. Gordon would exploit this story.[29]

By posing to John Banks the question of whether or not the scrap of flag Edgar Wheeler contributed to the secretary could be a remnant of the famous regimental battle flag, Gordon would eventually gain access to the relic flag at the Connecticut State Capitol. As Banks discussed in a blog post, comparative analysis established that the Bingham fragment was not from the same flag. An exact match, however, was not necessary or really the point. It was powerful enough to imagine that this scrap came from an undocumented flag present at Antietam, blown to bits by Confederate artillery just like John and other soldiers’ bodies. It was more than enough to know how much battle flags meant to soldiers, exemplified by the actions of the 16th, and, as viewers were led to believe, to Edgar Wheeler, who had saved this scrap placed at the heart of his memorial gift to Wells Bingham.[30]

A second “relic” in the secretary is equally central to the piece’s meaning. The last sentence of the secretary’s dedicatory inscription states: “This memory plaque made from a shard of his knife”—as if Wells or another member of Company H salvaged it from the battlefield in the gruesome aftermath documented by Gardner and his team (see fig. 19). While pocketknife handles were often made of bone in the 1860s, this piece is unusually wide to have come from a “shard” of a pocketknife.[31]

Gordon’s placement of a soldier’s pocketknife at the heart of his fakery was a strategic decision designed to further enhance the secretary’s narrative of trauma. Most Union soldiers carried pocketknives, which they used frequently for cleaning fingernails, eating, cutting bandages, and more. But pocketknives also served an emotional and educational purpose. In the nineteenth century, boys used knives to make useful items, often for their households, experience a sense of agency, and generally practice being productive and industrious young men. With these habits ingrained in them, Civil War soldiers turned to pocketknives as a way to pass tense minutes, hours, and days of waiting—to march, to charge, to be released from enemy prisons. Ulysses S. Grant counted whittling among his “favorite occupations” during the excruciating hours preparing the battery during the Battle of the Wilderness in May of 1864; a journalist observed Grant “very composedly whittling a rail until the guns were placed to suit him” amidst steady Confederate fire. In Civil War prisons, as one Union officer recalled of his time at Libby Prison in 1863, “carving bone” kept “minds and hands busy, which was everything in this place.” Soldiers in Connecticut had especially strong connections to the culture surrounding pocketknives because the western Naugatuck Valley was the center of manufacturing for folding knives in the United States beginning in the 1840s. On the secretary, the scrap of pocketknife could be interpreted through the lenses of John’s youthfulness, his boyhood in Connecticut, and his experiences as a soldier.[32]

Andersonville, where many from the 16th Connecticut Regiment were imprisoned, was well known for its whittling culture. Not only were many of the relics collected by Clara Barton fashioned with pocketknives, but POWs there also fostered a whittling culture with laurel roots available within the confines of the prison. On a material level these objects were relics of the places where their makers had been imprisoned; as the embodiment of a craft process, they were relics of a strategy for alleviating the psychological effects of imprisonment. Soldiers carried their carvings home, where they became personal mementos and gifts. A spoon carved at Andersonville by a member of the 16th Connecticut conveys how much men were able to accomplish with simple tools (fig. 28). Carved motifs include the name Sumter, the official name of Andersonville Prison, the date of 16th’s capture at the Siege of Plymouth, the names of several men in the 16th, and a five-pointed star. POW whittlers often focused on simple patriotic imagery, much like the star shapes Gordon repeated with calculating obsessiveness on the surface of the Bingham secretary. Indeed, Gordon’s many hand-carved elements evoke several Civil War POW whittling cultures. The bone letters and symbols are made in the same material used by Union officers at Libby Prison, who whittled cow bones dredged from their meals (fig. 29). The secretary also features abalone, a material carved by Confederate POWs imprisoned on Johnson’s Island in Lake Erie (figs. 30–31). Gordon had done his homework, moving deftly among Civil War soldiers’ whittling materials to ornament the secretary.[33]

Whittling had an afterlife among veterans, so it was no stretch to imagine soldiers who had served in the 16th Connecticut contributing to the secretary. When in 1910 Susan Elizabeth Tracy published Studies in Invalid Occupation, the first book on occupational therapy written in the United States, she observed that when Civil War veterans were too old to participate in the workforce, they struggled to find activities that made them feel as though they were valuable members of their households. Tracy held up veterans who whittled as an important and illuminating exception. She remembered that in the 1890s in her hometown, “a group of veterans used to meet daily around a little stove in our store,” and “their unvarying occupation was whittling.” She particularly noted their interest in carving napkin rings, a common trinket carved by POWs. Tracy had recorded an instance of veterans relying on the palliative habits that had carried them through the war, down to the very domestic objects they made.[34]

The narrative of whittling present in the secretary illuminates the logic behind Gordon’s source materials and his deft manipulation of significant Civil War imagery, materials, and narratives. It was historically sensitive and timely to view the secretary through the lens of negotiating trauma through making. It also, importantly, was a story about objects soothing pain in that the secretary was a gift from friends meant to alleviate Wells Bingham’s suffering. Certainly, it offered evidence of a narrative about art many museums have adopted—that works of art, and by extension the museums that house them, can promote empathy, redress wrongs, and, by representing painful chapters in personal and national histories, alleviate their painful legacy. But Gordon’s fakery missed an important element of the therapeutic legacy of craft in the Civil War: the meaning was in the making. Families did not mourn their war dead in their homes by receiving elaborate, memorial gifts from non-relatives. Instead, they made them. Even stony Civil War monuments, which might seem to stand as a significant exception to this process of mourning by making, were activated at annual ceremonies through the garlands and wreaths woven and draped on the monuments by widows’ memorial associations (fig. 32).[35]

One of the best-documented domestic soldier’s memorials, the Bowditch “memorial cabinet” made by the parents of Nathaniel Bowditch between 1865 and 1875 in Salem, Massachusetts, sheds light on the centrality of process to the meaning of family memorials. (Drew Faust has attributed the memorial solely to Nathaniel’s father, the abolitionist and physician Henry Ingersoll Bowditch, but the documentary record indicates Nathaniel’s mother Olivia and his fiancée Katharine also assembled its contents.) Nathaniel died in the spring of 1863 from wounds suffered at the Battle of Kelly’s Ford. He was embalmed, transported back to Salem, and buried there that same year, and as the war came to an end, the Bowditches began to create the “memorial cabinet.” Of all known Civil War memorials, the Bowditch cabinet is the closest in form to Gordon’s falsified secretary.[36]

Although the Bowditch cabinet itself no longer survives, much of its contents are included among the Bowditch papers at the Massachusetts Historical Society, and the cabinet is visible in a photograph taken of the family’s library in the 1880s (fig. 33). The memorial cabinet stands flanked by busts of Nathaniel’s namesake, Nathaniel Bowditch Sr., and the scientist Pierre-Simon Laplace, and behind these busts are pikes, which were relics of John Brown’s raid given to Bowditch by a friend in honor of his abolitionist politics. Inside the cabinet, the Bowditches kept albums they had compiled containing photographs of family and Civil War officers, relics relating to Nathaniel’s life, including his bloody handkerchief from the day he was fatally wounded, and photographic portraits of Nathaniel. The memorial also contained historical objects from the Bowditch family’s past, including the musket Nathaniel’s grandfather used in the Revolutionary War.[37]

Drew Faust has examined the papers of Henry Bowditch, finding a father struggling to accept his son’s death. In his mourning, Bowditch found solace in the poem “My Child,” written in 1840 by John Pierpont in memory of his own son. The poem describes the haunting quality of grief in his family home. A deceased son’s “sunshiny head | Is ever bounding round my study chair . . . . With tears, I turn to him, | The vision vanishes—he is not here!” The poem’s first and last stanzas begin with the refrain “I cannot make him dead!”, a phrase that alludes to the way mourning was a process of “making” rather than a passive experience. This sense that realizing a terrible loss could be helped by an embodied process of mourning through making is echoed in Bowditch’s anguished writing about making the memorial cabinet. In reference to compiling the materials of the cabinet, he wrote to a friend, “the labor was sweet, it took me out of myself.” To comprehend Nathaniel’s death, the Bowditches embarked upon the making of a memorial cabinet, in which they gathered traces of the world that had surrounded their once-living son, and in doing so, created an associational space to comprehend his death. By exploiting real stories of loss like the Bowditches’, Gordon did more than construct a fake; he created a willing suspension of disbelief that titillated the art market and clouded observers’ abilities to appropriately pause and vet the secretary. The forger went to great exertions to manipulate and match the smallest of fabricated details and embellishments into a legitimate history, and in doing so he dishonored the Bingham family legacy and momentarily fooled the art world.[38]

Conclusion

Harold Gordon transformed a real object and a deeply personal history into a “folk art” spectacle. By focusing on the Bingham brothers, he tapped into a nostalgia not simply for the Civil War, but for a way of commemorating it that centers the heroic sacrifice of white, Union soldiers and that was eclipsed at the 150th anniversary by a heightened interest in the war as a time of racial reckoning. The evidence of mental anguish in Wells A. Bingham’s real history was swept up in the admirable aim of museums to examine the Civil War through the modern lens of mental trauma. With great effort, the Massachusetts-based antiques dealer and picker made scholars, dealers, and museum professionals unwitting participants in his fakery.

If we take the Bingham secretary as an opportunity to examine what made the Americana market and art world ready victims of Gordon’s fakery, generative questions arise. To tell relevant stories, how might curators of historical art foster initiatives that foreground perspectives on the legacy of the Civil War across a wider range of demographics? To explore histories of emotion, how might art museums embrace existing objects that are often excluded from art museums but nonetheless would be enriched by analysis and interpretation that prioritize their status as crafted objects? As more museums continue to grow collections and make space for objects that challenge, rather than affirm, collecting priorities and perceptions of value, how might we seize the collective opportunity to reshape public perceptions of the Civil War and its legacy? In openly addressing the vulnerabilities exposed by the Bingham secretary, glimpses of Whitman’s “real war” become possible.

Kevin M. Levin, “Has It Been an ‘Anemic’ Civil War Sesquicentennial?”, Civil War Memory, March 11, 2014, http://cwmemory.com/2014/03/11/has-it-been-an-anemic-civil-war-sesquicentennial/. Eleanor Jones Harvey, The Civil War and American Art (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian, 2012). Mark E. Neely Jr., in Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography. 138, no. 2 (2014): 223–24. Ta-Nehisi Coates, “The Case for Reparations,” Atlantic Monthly (June 2014): 54–71. Clayton Butler, “An Interview with Gary Gallagher,” American Battlefield Trust, https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/interview-historian-gary-gallagher, accessed August 15, 2021. Cameron McWhirter, “For Civil-War Buffs, 150-Year Anniversary Has Been Disappointing So Far,” Washington Post, April 10, 2014, https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052702303847804579481323991648630.

Allan Katz, “The Bingham Family Civil War Memorial Secretary,” Winter Antiques Show Object Essay 2015, Curatorial Object File, Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, Conn.

John Bank’s Civil War Blog, November 26, 2011, https://john-banks.blogspot.com/2011/11/faces-of-civil-war-bingham-brothers.html. Allison Meier, “A Folk Art Desk Mourns the US Civil War’s Bloodiest Day,” Hyperallergic, March 13, 2015, https://hyperallergic.com/190374/a-folk-art-armoire-mourns-the-us-civil-wars-bloodiest-day/.

Alyce Perry Englund, “Speaking Through Wood,” Antiques 182, no. 4 (September 24, 2015): 92–95 ; see also https://www.themagazineantiques.com/article/speaking-through-wood/. “Bingham Secretary: A Folk Art Masterpiece Acquired by Wadsworth Atheneum,” Antiques and The Arts Weekly, March 27, 2015. Walt Whitman, Specimen Days & Collect (Philadelphia: Rees Welch and Co., 1882–1883), p. 80. Sylviane Gold, “Pieces of the Civil War with the Power to Unsettle: A Review of Colts and Quilts at the Wadsworth Atheneum,” New York Times, March 23, 2012, https://www.nytimes.com/2012/03/25/nyregion/a-review-of-colts-quilts-

at-wadsworth-atheneum-in-hartford.html.

Clayton Pennington, “Fake Civil War Masterpiece: A Tale of Two Photographs,” Maine Antique Digest, February 26, 2018. Following a call from Clayton Pennington, Katz contacted Gordon, who confessed “that the piece and his research was a fabrication.” Gordon’s confession was also published in the March 11, 2018, issue of the New York Times: “I’m going to keep this short. I did it. I made it. I did the provenance, the whole bit. . . . I Cheated.” (https://www.nytimes.com/2018/03/11/arts/i-cheated-says-woodworker-who-fooled-the-antiques-experts.html.) There is evidence that a lasso tool was used on the digital image showing the unembellished secretary, although the purpose is not known.

Erik Ofgang, “The Great Antique Hoax: How a Forged Civil War Piece Fooled the Experts,” Connecticut Magazine (February 6, 2021), https://www.connecticutmag.com/the-connecticut-story/the-great-antique-hoax-how-a-forged-civil-war-piece-fooled-the-experts/article_ebfe9eca-762a-11eb-a1ce-1f266e907723.html. The authors thank Assistant U.S. Attorney Hal Chen for securing the return of these documents to the Wadsworth Atheneum.

Similar mathematical equations or numerically based scribbles were written on the top of the lower section and drawer interiors of the secretary. Photograph of John Bingham, and verso of the Personal War Sketch. “Damage Done by Fire, W. A. Bingham & Co. Lose $15,000 . . . ,” The Paper Mill and Wood Pulp News 23, no. 41 (October 13, 1900). “Family Away, Kills Self. Wells A. Bingham, Worried Over Business, Commits Suicide,” New York Times, August 17, 1904 (database print of the original article); transcription, letter from Wells A. Bingham, Sharpsburg, Maryland, to Elisha C. Bingham, East Haddam, Middlesex County, Connecticut, September 20, 1862; “This Blank is to be used by the Comrade and Post Historian In preparing the Sketch to be transcribed to the Record Book,” Harold Gordon, Bingham Secretary Desk research binder and object prospectus, Curatorial Object File, Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art [hereafter BSOF].

Gordon claimed not to have known that this correspondence existed, and Banks described the letter’s discovery in detail in a subsequent post announcing the Wadsworth’s acquisition. John Banks, conversation with Brandy S. Culp, June 15, 2021. John Banks’s Civil War Blog, April 21, 2015, http://john-banks.blogspot.com/2015/04/furniture-with-antietam-tie-purchased.html. The typescript with Gordon’s highlights was included in his research binder, but the color photocopy of the original letter was not. Transcribed letter from Wells A. Bingham to Elisha C. Bingham, September 20, 1862, BSOF.

R. Ruthie Dibble, email message “RE: Wells A. Bingham Letter” to Stephanie E. Gray, Museum and Library Services, Antietam National Battlefield, July 2, 2021.

Typical of his fakery, Gordon included contrived “facts” in his research binder. In a timeline he wrote, “HIS POST HISTORY WRITTEN IN LIVINGSTON NEW YORK in lawyers office AND DATED APRIL 13, 1904.” “Personal War Sketch,” BSOF. For questionnaires, see Jon-Erik Gilot, “Personal War Sketch Questionnaires,” Carnegie Free Library Espy Post Manuscript Collection, Carnegie, Pa., https://carnegiecarnegie.org/civil-war-room/manuscript-collection/personal-war-sketch-questionnaires/.

Harold Gordon, “Notes on Bingham Secretary,” 2013, BSOF. Stephen R. Smith, Frederick E. Camp, et al., ”History of the Sixteenth Regiment C.V. Infantry. Written by Liet.-Col. B. F. Blakeslee . . . ,” Records of Service of Connecticut Men in the Army and Navy of the United States During the War of the Rebellion (Hartford, Con.: Case, Lockwood and Brainard Company, 1889), pp. 617–618. The forger placed a version of this account by Blakeslee, found online, in the research binder, serving as his object prospectus. The chronology in this Post History Form closely follows Blakeslee’s account, and if the document was forged onto a blank 1890s form (readily available on the market), this account may have been the source of information.

“Family Away, Kills Himself,” New York Times, August 17, 1904. According to the article, “worry over money matters is said to have been the cause which induced him to end his life.”

“Damage Done by Fire,” Paper Mill and Wood Pulp News. Curatorial Object File, Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Harold Gordon, Bingham Secretary Desk research binder, “Family Away, Kills Self. Wells A. Bingham, Worried Over Business, Commits Suicide,” August 17, 1904, New York Times (database print of the original article with markings by Gordon).

The signature line reads, “EDGAR M. BINGHAM | NORTHHAMPTON, MASSACHUESETTS | SEPTEMBER, 22 1972 |AGE 93.” Gordon also claimed that Edgar M. Bingham Jr. (1909–1989), director of antiques at Shreve Crump and Low Co., had inherited the secretary from his father, a coincidental connection between the Binghams and the antiques business that created a fascinating and seemingly predestined provenance. Gordon invented the story that he had purchased the secretary directly from family members following Edgar Bingham Jr.’s death.

Harold Gordon, email message “RE: 16 th C.v.I flag”to Eric Connery, Office of Legislative Management, Connecticut General Assembly, September 26, 2011; Harold Gordon, email message “RE: 16th CONNECTICUT MOMENTO [sic] MORI OBJECT” to Lesley J. Gordon, Ph.D., October, 5, 2011, BSOF. Eric T. Dean, Shook Over Hell: Post-Traumatic Stress, Vietnam, and the Civil War (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1997), p. 156.

William Barton to George Washington, August 28, 1878, Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/04-06-02-0429, accessed August 15, 2021.

National Archives, The Great Seal of the United States / Milestone Documents (Washington, DC: National Archives, 1986), pp. 1–2. John D. MacArthur, “Third Great Seal Committee—May 1782,” Great Seal, https://greatseal.com/committees/thirdcomm/index.html.

Pictures of popular personalities constituted one of the larger segments of the firm’s business. The most frequently depicted subjects were George Washington and Abraham Lincoln; however, group portraits, such as this one, were also widely collected. D’Amour Museum of Fine Arts, The Presidents of the United States, Nathaniel Currier, https://springfield

museums.org/collections/item/the-presidents-of-the-united-states-nathaniel-currier/, accessed August 15, 2021.

Englund, “Speaking Through Wood.”

The Bingham brothers’ Collected Military Service Records stored at the National Archives are necessary to verify their enlistment history, but the documents have not been available during the research timeline of this article due to pandemic closures. Bernard F. Blakeslee, History of the Sixteenth Connecticut Volunteers (Hartford: Case, Lockwood, and Brainard Company Printers, 1875), pp. 13–21. John Banks, Hidden Histories of Connecticut Union Soldiers (Mount Pleasant, S.C.: History Press, 2015), p. 54. Lesley J. Gordon, A Broken Regiment: The 16th Connecticut’s Civil War (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2014).

Lesley J. Gordon, “The Bad Luck Regiment: The 16th Connecticut Infantry,” Civil War Times (April 2015), https://www.historynet.com/bad-luck-regiment-the-16th-connecticut-infantry.htm. James Rosebrock, “Antietam Voices: The Cornfield,” 2013, https://jarosebrock.wordpress.com/maryland-campaign/antietam/the-cornfield/.

Alyce Englund, “Acquisition Report,” February 12, 2015, Curatorial Object File, Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art.

Didier Fassin, Prison Worlds: An Ethnography of the Carceral Condition (Hoboken, N.J.: John Wiley and Sons, 2017), p. 113; and, Robert D. Stolorow, “Worlds Apart: Dissociation and Traumatic Temporality,” Trauma Psychology (May 6, 2019), http://traumapsychnews

.com/2019/05/dissociation-and-traumatic-temporality/.

Dean, Shook Over Hell, pp. 79, 115, 148. Eric T. Dean, “Reflections on ‘The Trauma of War’ and ‘Shook Over Hell,’” Civil War History 59, no. 4 (December 2013): 414.

Drew Faust, This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War (New York: Penguin Random House, 2009), p. iv. Harvey, The Civil War and American Art, p. xiv.

Jeff L. Rosenheim, Photography and the American Civil War (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2013), pp. 7–15. William H. Frassanito, Antietam: The Photographic Legacy of America’s Bloodiest Day (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1978), pp. 126–38.

Franny Nudelman, “Photographing the War Dead,” in John Brown’s Body: Slavery, Violence, and the Culture of War (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2004), pp. 103–31. Steven Conn, “Narrative Trauma and Civil War History Painting, or Why Are These Pictures So Terrible?” Studies in the Philosophy of History 41, no. 4 (February 2003): 17–42.

The piece, as one scholar has written, was “Smith’s way of working through the events he had witnessed.” This comment, like that in Antiques regarding the Bingham secretary, reflects the interest in histories of trauma during the sesquicentennial years. Jeannine A. Disviscour, “Remembering Antietam: John Philemon Smith’s Shadow Box” Catoctin History 1, no. 1 (Fall 2002): 22–23.

Geraldine S. Caughman, QUI TRANSTULIT SUSTINET: Connecticut Battle Flag Collection, 2 vols. (Weatherfield, Conn.: Caughman Associates, 2006), 1: 153.

Gordon was aware that Lieutenant Colonel Bernard F. Blakeslee, the author of History of the Sixteenth Connecticut Volunteers, had written multiple accounts of the regiment’s captured colors, one of which he provided in his research binder. There is no evidence that Blakeslee and Bingham knew one another. Gordon also included a copy of the book History of Battle Flag Day, September 17, 1879, which detailed the momentous celebration in Hartford, Connecticut, on the seventeenth anniversary of Antietam. A mention of Mrs. Wells A. Bingham was included in this tome and noted by Gordon in his Bingham secretary desk description for Katz. She was indeed among the female volunteers at this event. Harold Gordon, email message to Leslie Gordon, July 16, 2011, with copied version of “Regimental History, Connecticut Sixteenth Regiment CV Infantry (Three Years), Written by Lieut. Col. B. F. Blakeslee, Late Second Lieutenant of Co. G, Sixteenth Connecticut Volunteers,” Harold Gordon, Bingham Secretary Desk research binder and object prospectus, BSOF. This text can easily be found online; see http://civilwardata.com, accessed June 30, 2021. Caughman, QUI TRANSTULIT SUSTINET. Caughman’s chapter on the 16th Connecticut was included in Gordon’s research binder and this passage highlighted, with the fact that some flag remnants remained in private hands underlined in red. Connecticut’s battle flags were initially painted by Frederick F. Rice on silk. However, sometime after 1862, Quartermaster General William Aiken began ordering embroidered flags from Tiffany and Co. Painted silk examples shattered and split particularly during winter. Tara M. Cantore, “Hall of Flags: Memorial to Connecticut’s Civil War Colors,” Connecticut Historical Society, https://connecticuthistory.org/hall-of-flags-memorial-to-connecticuts-civil-war-colors/, accessed June 30, 2021.

Michael W. Silvey, The Complete Book of U.S. Military Pocket Knives: From the Revolutionary War to the Present (Atglen, Pa.: Schiffer Publishing, 2015), pp. 6–51.

W. F. G. Shanks, Harper’s New Monthly Magazine 31 (June–November 1865): 74. Asa N. Hays, “War-Time Recollections (Third Paper),” Magazine of History 38, no. 24 (1914): 154. R. Ruthie Dibble, “Home Wars: Resistance, Trauma, and Memory in Domestic Arts of the Civil War Era” Ph.D. diss., Yale University, New Haven, 2020, p. 112. Edward T. Howe, “Connecticut Pocketknife Firms,” Connecticut Historical Society, https://connecticuthistory.org/connecticut-pocketknife-firms/, accessed August 15, 2021.

David R. Bush, I Fear I Shall Never Leave This Island: Life in a Civil War Prison (Gainesville: University of Florida Press, 2011). Dibble, “Home Wars,” pp. 88–138. John Lord Parker, Henry Wilson’s Regimental History of the Twenty-Second Massachusetts Infantry, the Second Company Sharpshooters, and the Third Light Battery, in the War of the Rebellion (Boston: Regimental Association, 1887), p. 91.

Susan Edith Tracy, Studies in Invalid Occupation: A Manual for Nurses and Attendants (Boston: Whitcomb and Barrows, 1910), pp. 124–5. Dibble, “Home Wars,” pp. 132–33.

Dibble, “Home Wars,” pp. 217–18.

The “nucleus” of the cabinet was a “large book containing a short memoir of my brother” that had been a gift to Olivia. The albums were “appropriately illustrated” by Olivia and Katharine. Henry Ingersoll Bowditch and Vincent Y. Bowditch, Life and Correspondence of Henry Ingersoll Bowditch, 2 vols. (Boston: Houghton and Mifflin Company, 1902), 2: 14, 26–7. Tamara Plakins Thornton, “Sacred Relics in the Cause of Liberty: A Civil War Memorial Cabinet and the Victorian Logic of Collecting,” in New England Collectors and Collections, edited by Peter Benes and Jane Montague Benes (Boston: Boston University, 2006), p. 189. Faust makes a compelling argument for the “therapeutic” purpose of the Bowditch memorial; see Faust, This Republic of Suffering, pp. 167–70.

Nathaniel Bowditch memorial photographs, Massachusetts Historical Society Photograph Collection, http://www.masshist.org/collection-guides/view/fap056, accessed April 15, 2018.

Faust, This Republic of Suffering, p. 170.