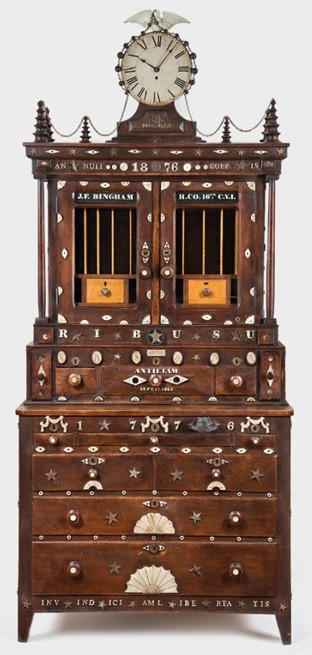

Harold Gordon, secretary, America, ca. 2010. Walnut, oak, ebony, and maple with tulip poplar, white pine, and maple; metal, glass, muslin, silk, bone, horn, and abalone. H. 95 1/2", W. 42 1/4", D. 19 3/4". (Courtesy, Chipstone Foundation, gift of Penny and Allan Katz; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Composite image showing a corner of Harold Gordon’s dining room with the secretary before and after alteration, Templeton, Massachusetts, ca. 2005. (Courtesy, Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art.) These low resolution images were the pictures of record that broke this story.

Portrait of unidentified sitters, America, ca. 1845. Daguerreotype and case. Case: 5 7/8" x 4 7/8" x 3/4" (closed); 5 7/8" x 9 3/4" x 3/8" (open). Harold Gordon claimed this daguerreotype was a portrait of the Bingham brothers’ grandparents.

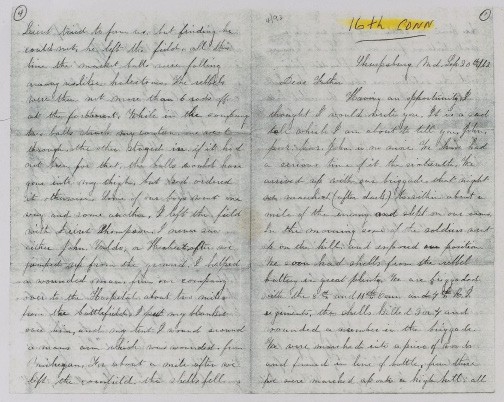

Photocopy of the first and fourth pages of the letter purportedly written by Wells A. Bingham to his father, September 20, 1862. (Courtesy, Antietam Battlefield Library Vertical Files.)

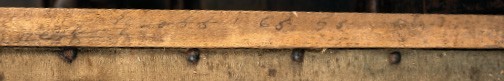

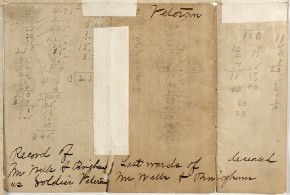

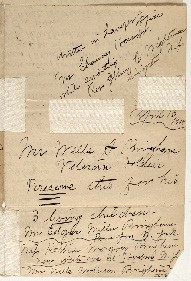

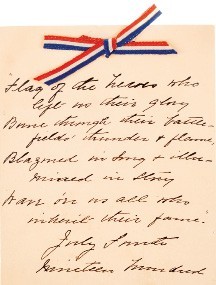

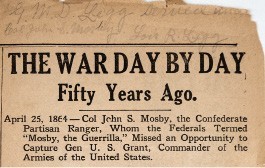

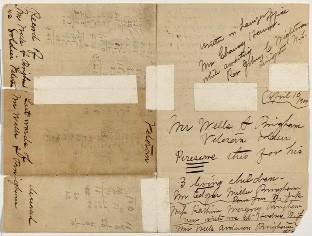

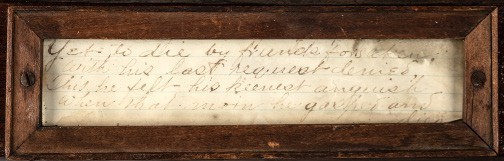

Comparisons of handwriting by Harold Gordon and Wells Bingham

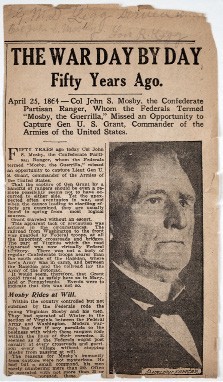

with inscriptions on the secretary and accompanying documents: 1. Numbers written in pencil on side of desk slide; 2. Numbers on verso of the Personal War Sketch; 3. Phrases on verso of the Personal War Sketch; 4. Note in the secretary with red, white, and blue ribbon; 5. Notations on top of “the war day by day” article.

Comparisons of handwriting by Harold Gordon and Wells Bingham

with inscriptions on the secretary and accompanying documents: 1. Numbers written in pencil on side of desk slide; 2. Numbers on verso of the Personal War Sketch; 3. Phrases on verso of the Personal War Sketch; 4. Note in the secretary with red, white, and blue ribbon; 5. Notations on top of “the war day by day” article.

Comparisons of handwriting by Harold Gordon and Wells Bingham

with inscriptions on the secretary and accompanying documents: 1. Numbers written in pencil on side of desk slide; 2. Numbers on verso of the Personal War Sketch; 3. Phrases on verso of the Personal War Sketch; 4. Note in the secretary with red, white, and blue ribbon; 5. Notations on top of “the war day by day” article.

Comparisons of handwriting by Harold Gordon and Wells Bingham

with inscriptions on the secretary and accompanying documents: 1. Numbers written in pencil on side of desk slide; 2. Numbers on verso of the Personal War Sketch; 3. Phrases on verso of the Personal War Sketch; 4. Note in the secretary with red, white, and blue ribbon; 5. Notations on top of “the war day by day” article.

Comparisons of handwriting by Harold Gordon and Wells Bingham

with inscriptions on the secretary and accompanying documents: 1. Numbers written in pencil on side of desk slide; 2. Numbers on verso of the Personal War Sketch; 3. Phrases on verso of the Personal War Sketch; 4. Note in the secretary with red, white, and blue ribbon; 5. Notations on top of “the war day by day” article.

Harold Gordon, Wells A. Bingham Personal War Sketch, ca. 2010. Ink on paper. (Courtesy, Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art.) Beginning in the late 1890s, GAR post officers began to distribute personal war sketch questionnaire forms at their annual reunions so that aging veterans could record their memories. No authenticated examples of GAR questionnaires completed in lawyers’ offices are known.

Verso of the Personal War Sketch illustrated in fig. 5.

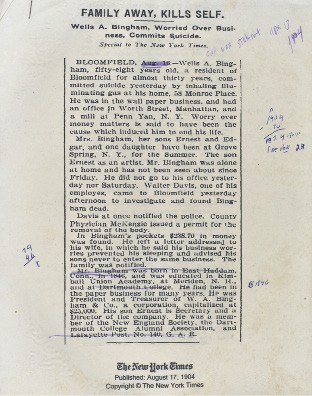

Article reporting Wells Bingham’s suicide, New York Times, August 17, 1904, with notes by Harold Gordon. (Courtesy, Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art.) W. A. Bingham and Co. filed for bankruptcy on September 4, just a few weeks after Wells Bingham’s death. His suicide on August 16 was close to the anniversary of his enlistment and the Battle of Antietam.

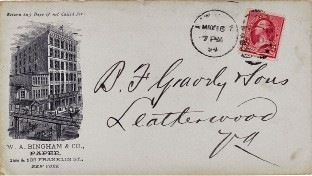

Envelope for Wells A. Bingham’s paper company, America, ca. 1900.

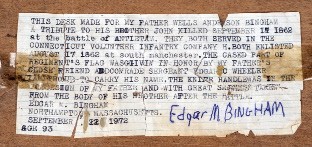

Typed note with Harold Gordon’s falsified Edgar M. Bingham signature pasted inside the center drawer of the secretary illustrated in fig. 1.

One of the newspaper clippings found inside the secretary illustrated in fig. 1.

Membership Badge to the Lafayette Post 140, New York Grand Army of the Republic, 1901. Silver and metal.

Detail showing the dedicatory plaque on the secretary illustrated in fig. 1. Bone.

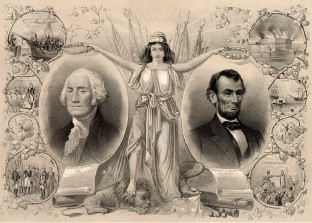

E. B. and E. C. Kellogg and George Whiting, The Eagle’s Nest. “THE UNION! IT MUST AND SHALL BE PRESERVED,” Hartford and New York, 1861. Hand-colored lithograph on paper. (Courtesy, Library of Congress.) “The Union Must and Shall Be Preserved” was also the title of a pro-Union song written in 1860 and set to the tune of “Star Spangled Banner.”

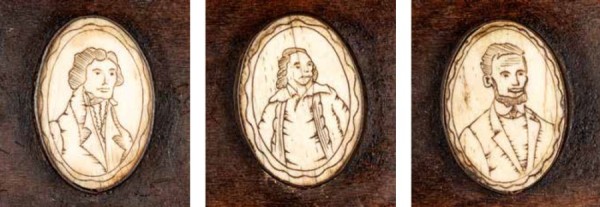

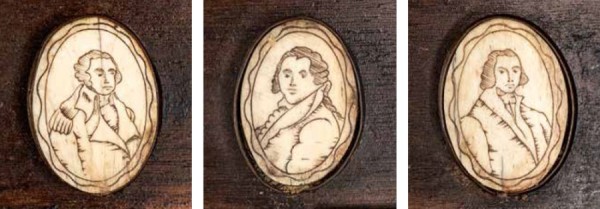

Composite illustration showing the portraits of Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, Abraham Lincoln, George Washington, Alexander Hamilton, and an unidentified individual, inlaid in bone on the secretary illustrated in fig. 1.

Composite illustration showing the portraits of Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, Abraham Lincoln, George Washington, Alexander Hamilton, and an unidentified individual, inlaid in bone on the secretary illustrated in fig. 1.

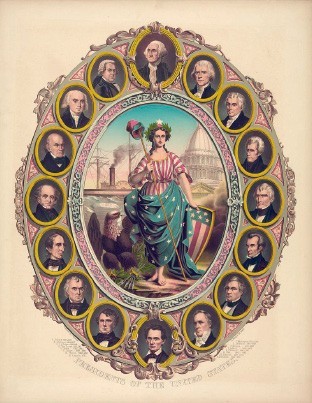

Presidents of the United States, Philadelphia, 1861. Lithograph on paper. 21" x 27". (Courtesy, Seth Kaller, Inc.) Augustus Feusier produced the lithograph and Francis Bouclet published the image.

Kimmel and Forster, Columbia’s Noblest Sons, New York, 1865. Lithograph on paper. 16" x 20". (Courtesy, Library of Congress.)

Note with lyrics from the song “The Little Major” by Henry Work, written and composed in 1863.

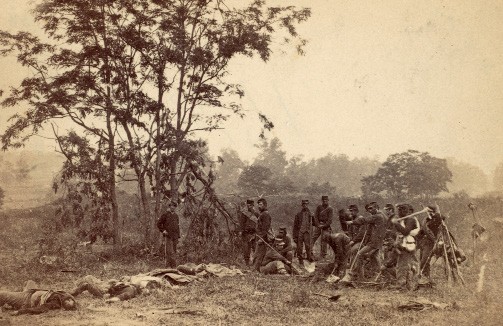

Alexander Gardner, Burying the Dead on the Battlefield of Antietam, September 1862. Albumen silver print from glass negative. 2 13/16" x 3 15/16". (Courtesy, Metropolitan Museum of Art.) In this image from Gardner’s series The Dead of Antietam, a Union burial detail prepares to inter Federal dead killed in the cornfields of David Miller’s farm.

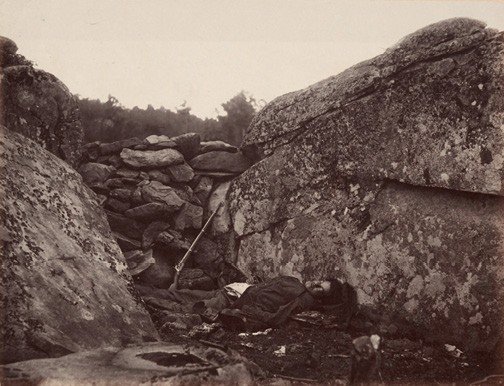

Alexander Gardner, Home of a Rebel Sharpshooter, Gettysburg, from Gardner’s Photographic Sketchbook of the War, 1865. Albumen silver print. 6 13/16" x 8 13/16". (Courtesy, Museum of Modern Art.) The photograph represents the tragic aftermath of the Battle of Gettysburg by focusing on a single dead soldier lying inside what Gardner called a “sharpshooter’s den.” Later analysis revealed that he had staged the image to intensify its emotional effect. Gardner moved the soldier’s corpse, propped up his head so that it faced the camera, and placed his own rifle next to the body.

Peter Frederick Rothermel, The Battle of Gettysburg, America, 1870. Oil on canvas. 16' x 32'. (Courtesy of the State Museum of Pennsylvania, Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission.) The Public Ledger, a Philadelphia newspaper, was shown the painting before the opening: “In conception and execution it well deserves the praise it has largely received from competent art critics, at perhaps being the best as well as the largest war picture on this side of the Atlantic.”

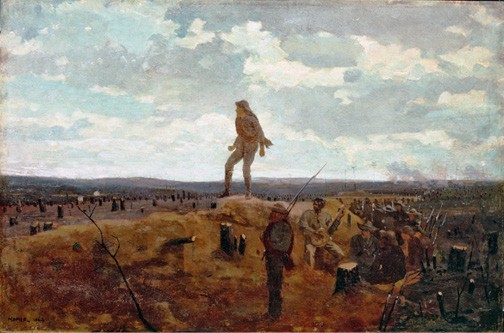

Winslow Homer, Defiance: Inviting a Shot Before Gettysburg, America, 1864. Oil on panel. 12" x 18" (unframed). (Courtesy, Detroit Institute of Art.) Winslow Homer served as a war correspondent for Harper’s Weekly magazine during the Civil War. Over the winter of 1864–1865, he traveled to Petersburg, Virginia, to sketch the Union siege of the city. Here, a young Confederate soldier taunts the opposing force. Having endured months of trench warfare, the soldier stands defiantly and challenges the distant Union sharpshooters to fire at him.

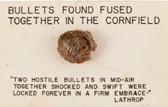

Bullets found fused together at Antietam, Washington County, Maryland, 1862. (Courtesy, Heritage Auctions.)

Brady and Company, Relics of Andersonville Prison, America, June 1866. Albumen silver print from glass negative. 8 11/16" x 7 7/16". (Courtesy, Metropolitan Museum of Art.) To support her effort for proper burial of the Andersonville dead, and to raise money for veteran relief in general, Clara Barton displayed and sold souvenirs of Andersonville. The largest item for sale was a portion of the infamous Dead Line, a wooden fence that prisoners were prohibited from crossing on pain of death.

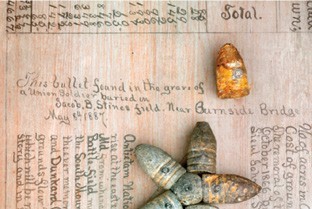

John Philomen Smith, Shadowbox of Antietam Relics, America, 1886. Wood, pencil, paint, metal, fabric, found objects. H. 39", W. 34", D. 5". (Courtesy, Maryland Historical Society.) John Philemon Smith was seventeen years old when he witnessed the Battle of Antietam. He spent the rest of his life as a teacher and historian of that single day of battle. The text inside the box records the dedication of the Antietam National Cemetery in 1867 and includes a list of the Union soldiers who died at Antietam. The centerpiece is a miniature replica of the Private Soldier Monument, installed at the cemetery in 1880.

Detail of the Shadowbox of Antietam Relics illustrated in fig. 25.

Detail of the fraudulent battle flag remnant mounted in a tin can on the secretary illustrated in fig. 1.

Spoon carved by a 16th Regiment Connecticut Volunteer infantryman, America, May and September 1864. Diffuse porous hardwood. L. 5". (Courtesy, Cowan Auctions.) The spoon is carved with branching leaves, a shield with eagle’s head, an inscription reading “Sumter Prison” around end, “Higgins | Waldo | Dowd | Macinnes | Whitney | Duane | Prisoners | Of | War” on one side and “Qui Trans Sus” on the underside near the end. Near the bowl on the underside is another inscription reading “Captured | April 20th | 1864.” The underside of the bowl has a carved five-pointed star.

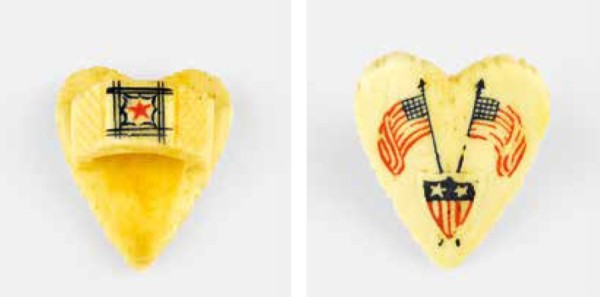

James H. Gagan, signet ring, America, 1864. Bone and ink. (Courtesy, American Civil War Museum.) Gagan, a Union officer, carved this ring from a bone while he was imprisoned at Libby Prison, Richmond, Virginia.

Detail showing the use of abalone on the secretary illustrated in fig. 1

Lieutenant Robert Smith, necklace, Johnson’s Island, Ohio, 1864. Hard rubber and shell. (Courtesy, Heidelberg University.) Robert Smith was one of the more skilled and prolific whittlers of the Confederates imprisoned at Johnson’s Island. Men at Johnson’s Island most often worked in hard rubber but often augmented it with abalone shells found on the island’s shore. Friends and descendants of Johnsons Island Cival War Prison.

Stereoview photograph showing the Memorial Day observance at Civil War Soldiers’ Monument in Paris, Maine, May 30, 1876. (Courtesy, Maine Historical Society.) For Memorial Day observances, including the speech-making captured in this photograph, the obelisk has been draped in wreaths, garlands, and American flags, activities often organized by widows’ memorial organizations.

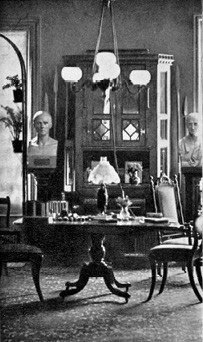

Library at 113 Boylston St., showing the “Memorial Cabinet” and the busts of La Place and Nathaniel Bowditch, in Vincent Yardley Bowditch, Life and Correspondence of Henry Ingersoll Bowditch, 2 vols. (Boston: Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1902), 2: 28. (Courtesy, Archive.org.) Standing against a wall behind a library table and chairs, the cabinet is tall, with crenulated molding at the top and glazed doors on three sides. A pitcher of flowers rests on it, seemingly in front of framed photographs. The Bowditches were an elite Boston family; Gordon invented a “folk” version of this cabinet to reflect the Bingham family’s lower-class status.