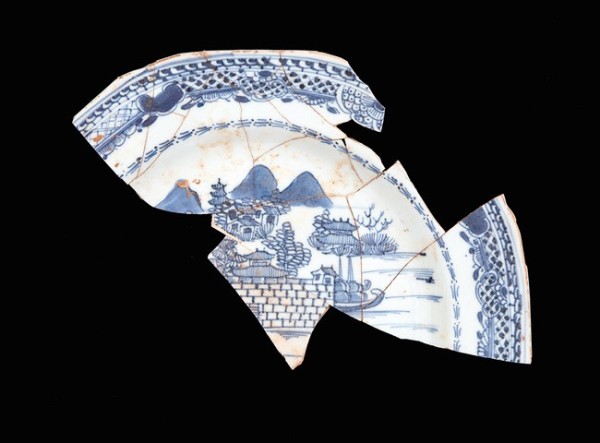

Dish, Jingdezhen, China, 1770–1790. Hard-paste porcelain. L. 14 1/2“ . (Courtesy, James Madison’s Montpelier; photo, Robert Hunter.) The dish was excavated at James Madison’s Montpelier.

Dish, Jingdezhen, China, 1770–1790. Hard-paste porcelain. L. 17 3/4“ . (Courtesy, Reeves Museum of Ceramics, Washington and Lee University, Gift of Bruce C. Perkins; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Plate, Jingdezhen, China, 1770–1790. Hard-paste porcelain. D. 10". (Courtesy, James Madison’s Montpelier; photo, Robert Hunter.)

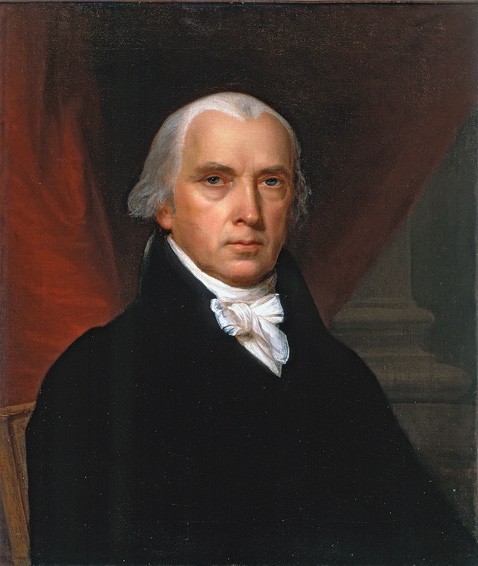

John Vanderlyn (1775–1852), James Madison, 1816. Oil on canvas. 26 x 23 3/16“. (White House Collection, White House Historical Association.)

Gilbert Stuart (1755–1828), Dolley Madison, 1804. Oil on canvas. 29 3/16x 24 1/8". (White House Collection, White House Historical Association.)

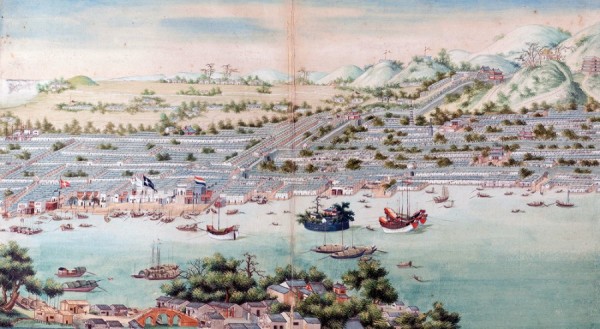

Unidentified artist, View of Guangzhou, ca. 1770. Gouache on paper. 21 1/2 x 12 1/2“. (Courtesy, Martyn Gregory Gallery, London.)

Drone photograph of the main house and grounds, 2021. The archaeological deposits are: (1) the main trash deposit containing plates; (2) the trash deposit in the back lawn from which the larger section of the dish illustrated in fig. 1 was first excavated; and (3) the slave quarter where the remaining pieces of the dish were found. (Photo, Montpelier Foundation.)

Plates, Jingdezhen, China, 1780–1800. Hard-paste porcelain. D. 10". (Courtesy, James Madison’s Montpelier; photo, Robert Hunter.)

GUANGZHOU, HISTORICALLY known to Europeans and Americans as Canton, was China’s largest international port in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. It is located some seventy miles up the Pearl River in southern China, and from 1757 to 1842 it was the only Chinese port open to foreign merchants. Views of the city, on canvas, paper, lacquer, or porcelain, were popular souvenirs for those few Westerners who had been there, and were a source of information on China’s landscape, architecture, and people for those who had not. Those images traveled far and wide. A set of porcelain decorated with a scene of the Dutch Folly Fort—one of the landmarks of Guangzhou’s waterfront—made it as far as the Virginia Piedmont, where it was owned by James Madison (1751–1836), the fourth president of the United States, and his wife, Dolley Payne Todd Madison (1768–1849) (figs. 1–5).

Known in China as Haizhu (“Pearl of the Sea”), the Dutch Folly Fort stood on a small island just downriver from the western suburbs of the city where the hongs—the waterfront buildings that served as offices, storehouses, and residences for European and American merchants—were located. Built sometime in the mid-seventeenth century, the fort housed a garrison of soldiers, a temple dedicated to Li Maoying, a Song-dynasty official, and a grove of banyan trees. Regarded as one of “the eight scenic spots of Canton,” it was a key landmark of the city’s waterfront until its deliberate demolition in 1856–57 during the Second Opium War between China and the Western powers.[1]

The origins of the fort’s European name are unknown but could stem from the fact that the Dutch delegation to China in 1655 anchored nearby and was reported to have committed the “folly” of trying to fortify the island in violation of Chinese orders.[2] The name might also come from the fact that it was viewed by many as being poorly fortified; one Swedish merchant described it in 1773 as “preserved by high stone-walls, which seem to have been erected more for decoration than real use, because neither these nor the walls which enclose the town would seem to be of the least protection in times of war.”[3]

Whatever its military value, the Dutch Folly Fort and another fort farther downriver marked the anchorage for many of the ships trading in Guangzhou (fig. 6); the American merchant William Hunter recounted that “between them, for a distance of about a mile and a half, on the H¯o-Nam side of the river, might be seen . . . tiers of those enormous sea-going junks, which with the monsoons made regular voyages to ports on the coast of China, and southerly to the Malay Peninsula, to Luzon, Java, the Spice Islands, Macassar, Celebes, &c.”[4]

The Dutch Folly Fort, surrounded by oceangoing junks and smaller vessels, appeared on a range of porcelain objects made in the last quarter of the eighteenth century. A number of pieces survive, and the minor variations in the border and style of painting suggest that several services were made over a period of time or by different workshops.[5]

At least one set—now represented by a dish and a plate—was owned by James and Dolley Madison (see figs. 1 and 3).[6] Recovered archaeologically from the grounds of Montpelier, the Madisons’ home in central Virginia, the pieces had been used and discarded sometime between 1797 and 1808, when the trash pit that some of the fragments had been thrown into was closed and covered by new landscaping (fig. 7). Located on the perimeter of a service yard adjacent to a flanking dependency to the mansion, the trash deposit rests atop rubble fill dating to the construction of Montpelier’s front portico in 1797, and is likely associated with the Madisons’ return from Philadelphia following their marriage and James Madison’s first retirement from the U.S. legislature. In 1808 this dependency was torn down to make way for a new landscaping scheme; the trash deposit was covered with brick rubble from masonry repairs made to the mansion that same year. As such, the trash deposit has a firm date to after the Madisons leave Philadelphia but prior to their moving into the White House in 1808.

It is likely that the Madisons acquired the service in Philadelphia, where they resided from the time of their marriage in 1794 until they moved to Montpelier in 1797. Philadelphia was one of the main American cities connected with the China Trade, and there would have been a plentiful supply of export porcelain in the city’s shops, as well as individuals with the means and connections to acquire pieces decorated with specific scenes like the Folly Fort.

Archaeological evidence shows that the Madisons combined their Folly Fort–decorated pieces with blue-and-white porcelain decorated with other generic Chinese landscape scenes. Among them was a service, finely painted with what is known as the Fitzhugh border, that seems to have been the main dining set used by the Madisons at Montpelier between 1797 and 1808 (fig. 8). The high number of broken and discarded matching pieces likely represents a sizable set of 140 to 160 pieces.[7]

The large Folly Fort dish found in the trash deposit had a remarkable history following its breakage. Archaeologists recovered half of it in 2004, during excavations at the rear lawn of the mansion. Like the plates recovered from the trash deposit mentioned above, this dish was located below the rubble layer related to the 1808 masonry repairs to the mansion. Some six years later, during excavations at a slave quarter some 120 yards away and adjacent to the stable, archaeologists found fragments bearing a similar pattern. Trash deposits from the same quarter had a few Fitzhugh-pattern sherds that matched the pieces from the mansion trash deposit. When the Folly Fort fragments were compared with those found at the rear lawn, archaeologists found the pieces had been mended. It appears that when the dish was broken at the mansion, part of it was disposed of in the service yard to the rear of the mansion and the remainder was brought back to the slave cabin near the stable. Whether the individual who broke the dish decided to secrete the evidence away from the house to avoid punishment or used the broken remains for some other purpose will never be known. But it is likely the dish had significance either to the Madisons or the enslaved individual for its disposal to involve such a complex route of travel.

Following his presidency, James and Dolley returned to Montpelier. Among the retirement-era deposits at Montpelier (1818–1836), neither the Folly Fort set nor the Fitzhugh-pattern porcelain makes an appearance. Had either of those sets remained at Montpelier, one would expect their sherds to continue to be found in the many rich archaeological deposits recovered from that time period.[8] Their absence posits the strong possibility that the Madisons arranged for enslaved workers to bring the two sets to Washington, D.C. for the White House years in 1808. If that occurred, they presumably were lost when the British burned the White House on August 24, 1814.

Patrick Conner, The Hongs of Canton: Western Merchants in South China, 1700–1900, as Seen in Chinese Export Paintings (London: English Art Books, 2009), pp. 275–82; William Sargent, Views of the Pearl River Delta: Macau, Canton and Hong Kong (Hong Kong: Urban Council of Hong Kong, 1996), p. 184.

Conner, Hongs of Canton, pp. 275–82.

Carl Ekeberg, Capitaine Carl Gustav Ekebergs Ostindiska Resa, åren 1770 och 1771 (Stockholm, 1773), quoted in Kee Il Choi, “Painting and Porcelain: Design Sources for Hong Bowls,” in Caroline Bloch, ed., A Tale of Three Cities; Canton, Shanghai, and Hong Kong (London: Sotheby’s Institute, 1997), p. 41.

William C. Hunter, An American in Canton (1825–44) (Hong Kong: Derwent Communications, 1994), p. 20.

At least two other dishes are known and are illustrated in William R. Sargent, Treasures of Chinese Export Ceramics from the Peabody Essex Museum (Salem, Mass.: Peabody Essex Museums, 2012), pp. 145–46, and David Sanctuary Howard and John Ayers, China for the West: Chinese Porcelain and Other Decorative Arts for Export Illustrated from the Mottahedeh Collection, 2 vols. (New York: Sotheby Parke Bernet, 1978), 1:207–8. At least two plates, a saucer, and a saltcellar are also known. C.J.A. Jörg, Porcelain and the Dutch China Trade, translated from the Dutch by Patricia Wardle (The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1982), p. 70; Reeves Museum of Ceramics, Washington and Lee University (2005.7.2). These blue-and-white services might have been inspired by services that show the Dutch Folly Fort painted in overglaze famille-rose enamels. Donald L. Fennimore and P. A. Halfpenny, Campbell Collection of Soup Tureens at Winterthur (Winterthur, Del.: Henry Francis du Pont Winterthur Museum, 2000), p. 83.

Dish is the period-appropriate term for what we know as a platter.

This service is represented by nine plates and five dishes that were archaeologically recovered. The average ratio of unbroken to broken dishes over a period of several years is around 10:1, making the potential size of the service 140–60 pieces.

The trash deposit associated with the retirement-era dining room and sherds found adjacent to the homes for house slaves featured massive quantities of Canton wares and chinoiserie Bamboo and Peony transfer-printed ware. The Folly Fort and Fitzhugh pattern would have served as an excellent set to accompany the chinoiserie dinner wares used for entertaining by the Madisons and their enslaved during the retirement years. Matthew Reeves, “Scalar Analysis of Early Nineteenth-Century Household Assemblages: Focus on Communities of the African Atlantic,” in Beyond the Walls: New Perspectives on the Archaeology of Historical Households, edited by Kevin R. Fogle, James A. Nyman, and Mary C. Beaudry (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2015).