Inkwell, probably London, England, ca. 1843. Salt-glazed stoneware. L. 3 1/8". (Collection of the author; photo, John Ault.) The face of the molded inkwell is relief-decorated with a depiction of Marc Isambard Brunel’s tunneling shield, taken from the print source illustrated in fig. 12.

The reverse of the inkwell illustrated in fig. 1, with opposing simple impressed scrollwork. (Photo, John Ault.)

Top view of the inkwell illustrated in fig. 1, with a pair of foliate scrolls flanking a central aperture with two smaller apertures.

Advertising token, William Griffin, London, England, ca. 1843. Gilt brass. D. 5/16". (Photos, courtesy of the author.) Issued for the opening of the Thames Tunnel, this token features an engraving of two tunnels side by side with the words “thames tunnel / opened 1843” and, on the reverse, “THAMES TUNNEL / AND / OTHER / MEDALS / TO BE HAD OF THE / PUBLISHER / W. GRIFFIN / 25 / CHANGE ALLEY / CORNHILL LONDON.”

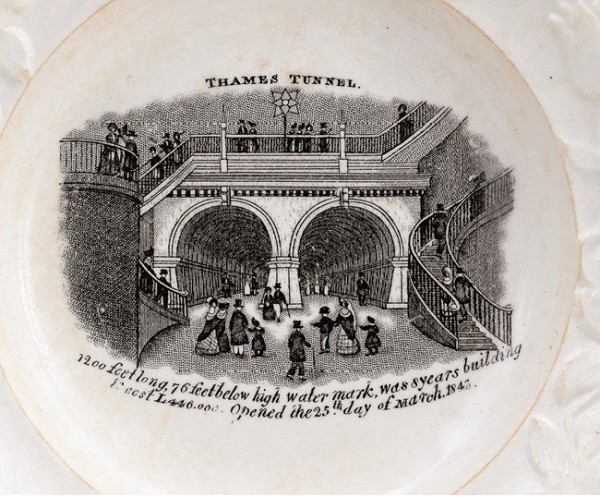

Plate, probably Staffordshire, England, ca. 1843. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 6". (Private collection; photo, Robert Hunter.) Various sizes and colors of this souvenir plate design were -produced. This example has a molded border of roses and tulips. Small mugs printed in black, blue, and green were also made and sold.

Detail of the transfer print on the plate illustrated in fig. 5. The interior transfer print derived from one of the many period engravings of the tunnel’s opening in 1843. It is inscribed THAMES TUNNEL. / 1200 feet long, 76 feet below high water mark, was 8 years building / & cost £446.000. Opened the 25th day of March.1843.”

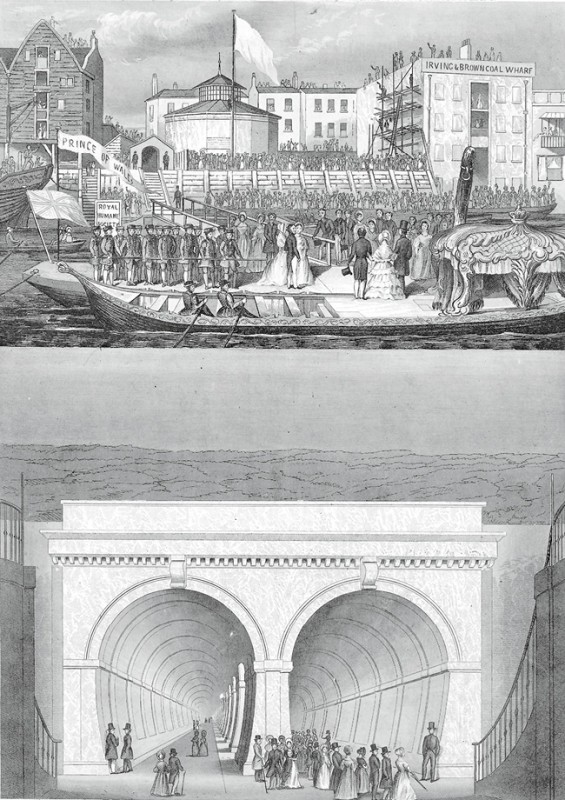

Engraving, London, England, ca. 1843. Porcelain card. 10 x 7U÷*". (Private collection.) Inscribed: “T. Brandon delineavit - Engraver, Printer, Publisher, 41 Thames Tunnel. London, 1843.” The upper view is labeled “Commemorative of the Visit of Her Most Gracious Majesty / QUEEN VICTORIA and HER LOYAL CONSORT / accompanied by other Illustrious & Distinguished Personages / on Wednesday, 26 July 1843.” The lower view is labeled “THAMES TUNNEL. /WAPPING ENTRANCE / 1200 feet long 76 feet below high water mark, was 8 Years building and cost £446.000 Opened March 25, 1843.” These so-called porcelain cards were printed on only one side of a piece of thick paper with a shiny coating and used around the middle of the nineteenth century, often as business cards. Although predominantly manufactured in Belgium, they were made in Britain and Germany as well.

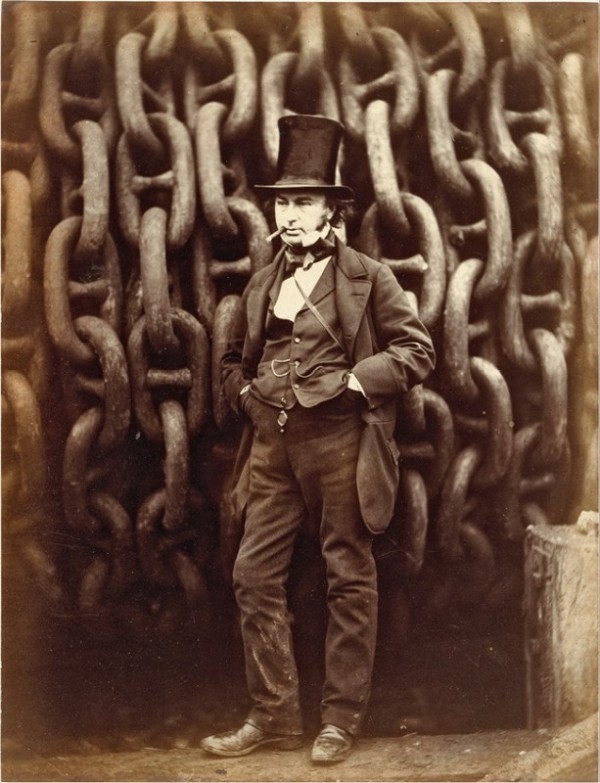

Robert Howlett (British, 1831–1858), Isambard Kingdom Brunel Standing before the Launching Chains of the Great Eastern, 1857, printed 1863–64. Albumen silver print from glass negative. 11 x 8 7/16". (Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gilman Collection, Purchase, Harriette and Noel Levine Gift, 2005.) Isambard Kingdom Brunel worked on the Thames Tunnel with his father, Sir Marc Isambard Brunel.

James Northcote (British, 1746–1831), Sir Marc Isambard Brunel, 1812–1813. Oil on canvas. 49 1/2 x 39". (National Portrait Gallery, London.)

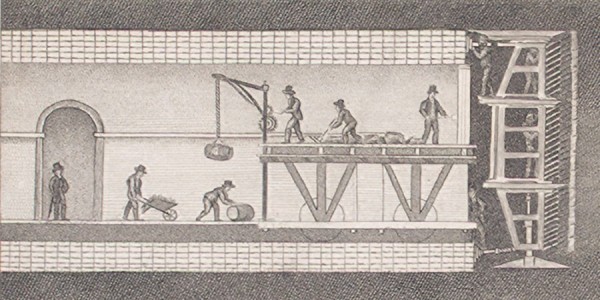

Engraving, “A longitudinal section of about 40 feet of the tunnel. . . . ,” from An Explanation of the Works of the Tunnel Under the Thames from Rotherhithe to Wapping, Thames Tunnel Company, London, 1836. (New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed May 17, 2021. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47dd-fd14-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a9.)This image is a side view of the tunneling shield used both to construct the Thames Tunnel and to facilitate the building of the tunnel’s brick walls.

Engraving, “This transverse section of the Thames, with a longitudinal section of the Tunnel beneath it. . . .”, from An Explanation of the Works of the Tunnel Under the Thames from Rotherhithe to Wapping, Thames Tunnel Company, London, 1836. (New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed May 17, 2021. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47dd-fd16-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99.) This image is a side view of the tunneling shield used both to construct the Thames Tunnel and to facilitate the building of the tunnel’s brick walls.

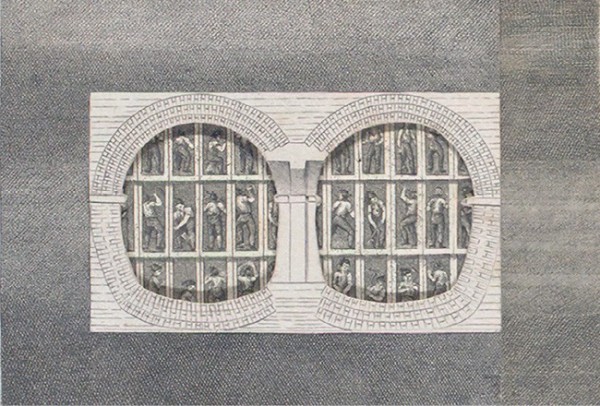

Engraving, “This view exhibits the workmen in the iron shield. . . .”, from An Explanation of the Works of the Tunnel Under the Thames from Rotherhithe to Wapping, Thames Tunnel Company, London, 1836. (New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed May 17, 2021. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47dd-fd13-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99.) This view shows the cells of the tunneling shield.

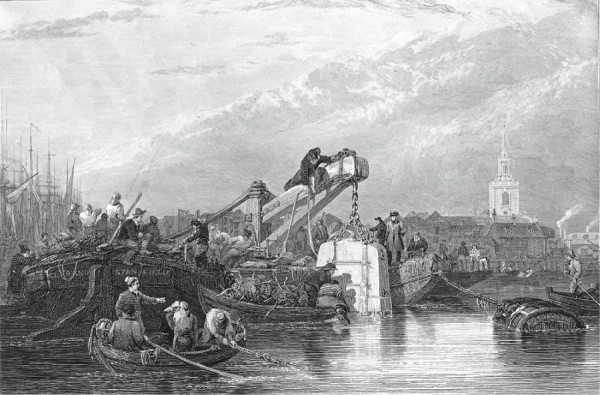

Clarkson Stanfield (English, 1793–1867), “The Diving Bell, Longman & Co., J. & A. Arch & G. Cooke, London [1834].” Etching and line engraving on paper. 6 1/2 x 8 7/8". Caption: “THE DIVING BELL / Used at the THAMES TUNNEL after the Irruption of the Water on the 18th of May. 1827. ROTHERHTHE church in the distance.” (Private collection.)

Attributed to George Jones (British, 1786–1869), Banquet in the Thames Tunnel, ca. 1827. Oil on board. 37 1/2 x 32 1/2". (Ironbridge Gorge Museum Trust.)

A very rare, salt-glazed stoneware inkwell recently appeared at auction (figs. 1–3).[1] Possibly this form was made to commemorate the opening of the Thames Tunnel in 1843, although it might have been produced before that date to help raise funds from public tours and banquets (figs. 4–7). The front panel of the inkwell depicts laborers in their “cells,” hard at work digging out the earth, a process that will be discussed later.

My guess is that this inkwell was produced at one of the London potteries, and was very crudely made with various kiln pulls and scars. Quality control at that time was not a major concern for most everyday objects; the main concern was that the item fulfill its purpose. The tunnel’s construction involved Isambard Kingdom Brunel, a young, ingenious civil engineer who became one of the most revered figures in British history and who changed the face of the English landscape with his groundbreaking constructions (fig. 8). In 2002 he was runner-up in the “100 Greatest Britons” poll carried out by the BBC, surpassed only by Sir Winston -Churchill.[2]

The tunnel itself had a long and torturous history.[3] At the start of the nineteenth century there was a pressing need for a new land connection between the north and south banks of the Thames in order to link the expanding docks on each side of the river. In 1799 the engineer Ralph Dodd tried but failed to build a tunnel between Tilbury and my hometown of Gravesend. However, in 1818 Sir Marc Isambard Brunel (fig. 9) and Thomas Cochrane patented the tunneling shield, a revolutionary advance in underground technology (fig. 10). Brunel produced a plan for linking Rotherhithe and Wapping, which would be dug using this new method (fig. 11). Financing was soon found from private investors—among them the Duke of Wellington—and the Thames Tunnel Company was formed in 1824. The project was to begin in the following year.

The first step was the sinking of a large shaft on the south bank at Roth-erhithe. It was dug by assembling aboveground an iron ring fifty feet in diameter. A brick wall was built on top of the ring, with a powerful steam engine surmounting it to drive the excavation pumps. The whole apparatus was estimated to weigh one thousand tons. The soil below the ring’s sharp lower edge was removed manually by Brunel’s workers. The whole ring then gradually sank under its own weight, slicing through the soft ground rather like an enormous pastry cutter. The shaft became stuck at one point during its sinking as the pressure of the earth around it held it firmly in position. As it required more to continue its descent, 50,000 bricks were added as temporary weights.

By November 1825 the Rotherhithe shaft was in place and work could begin using Brunel and Cochrane’s tunneling shield technology. This consisted of a massive iron ring, open at the back and sealed at the front by twelve huge frames (fig. 12). Each frame was divided into three stages to form thirty-six cells—with a workman in each cell, as seen in miniature on the inkwell (see fig. 1). The front of each cell was made up of wooden boards, which were removed one at a time by digging out the earth in front by hand. After a board was put back against the fresh earth, the workman went on to the next board. When all the boards were screwed in, the entire shield was moved forward using hydraulic jacks pressing on the ring (see fig. 10). In this way the whole mechanism advanced, holding up the tunnel while the walls behind were lined by skilled bricklayers.

Brunel and Cochrane’s type of excavation was much safer and faster than previous methods, but it was still slow, advancing only eight to twelve feet a week. Costs were managed by charging each of the up to eight hundred visitors per day one shilling to tour the works. The tour certainly would not have been a pleasant experience—the air was foul at the best of times, and made worse by the fact that in those days the Thames was literally an open sewer used to flush away effluent from the entire metropolis. Methane, hydrogen sulfide, and bacteria such as cholera were constantly seeping into the tunnel. There were also disastrous setbacks.

On May 18, 1827, a hole opened in the river floor and flooded the tunnel. Marc Brunel’s son, the legendary Isambard Kingdom Brunel, aged only twenty-one and in charge of the project after the chief engineer fell ill, lowered a diving bell from a boat to repair the hole at the bottom of the river, throwing bags filled with clay into the breach (fig. 13).[4] After the repairs were completed and the tunnel pumped out, a lavish banquet was held inside to celebrate and to raise more funds (fig. 14). It then flooded again on January 12, 1828, killing six men and almost drowning Isambard, who was saved by a contractor who broke a locked exit door down and dragged him out by his shirt collar. Strange to think how much history would have been changed if he had died that day. In August the money ran out and work stopped for seven years. When it resumed, in 1835, the shield was so badly corroded that it had to be replaced. Floods and fires continued to hamper work.

In November 1841 the tunneling finally was completed, having cost £454,000 for digging and £180,000—vast sums in those days—for gas lights, pumps to keep it dry, roadways, and spiral staircases. Eventually it was opened to the public on March 25, 1843, and hailed as the eighth wonder of the world. It went on to become a major tourist attraction, though open only to pedestrians.[5] The planned use by horse-drawn freight never took place; because further funding was not forthcoming, the complex access ramps could not be built.

The tunnel was not a financial success, and eventually it was sold to the East London Railway Company in 1865, later becoming the oldest segment of the London Underground. Today it is a Grade II listed monument and part of the London Overground serving Greater London and parts of Hertfordshire. The tunnel now has a museum and conducted tours are available during periods of maintenance.6 The staircase area was renovated by the architectural firm Tate Harmer and has become a unique venue for various arts events.

A version of this article appears in John Ault, “The Thames Tunnel Special,” in BBR [British Bottle Review] Magazine 166 (January–March 2021): 6–7.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/100_Greatest_Britons.

There are many excellent sources that relate the history of the Thames Tunnel. Of particular note are Mike Dash, “The Epic Struggle to Tunnel Under the Thames,” Smithsonian Magazine, January 3, 2012, available online at https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/the-epic-struggle-to-tunnel-under-the-thames-14638810/; and Andrew Mathewson et al., The Brunels’ Tunnel (London: Brunel Museum, 2006).

John H. Lienhard, “No. 1405: Brunel—Father and Son,” Engines of Our Ingenuity, available online at https://www.uh.edu/engines/epi1405.htm (accessed May 11, 2021).

An excellent analysis of the many symbolic functions tunnels had in popular culture can be found in Avid L. Pike, “‘The Greatest Wonder of the World’: Brunel’s Tunnel and the Meanings of Underground London,” Victorian Literature and Culture 33, no. 2 (2005): 341–67.