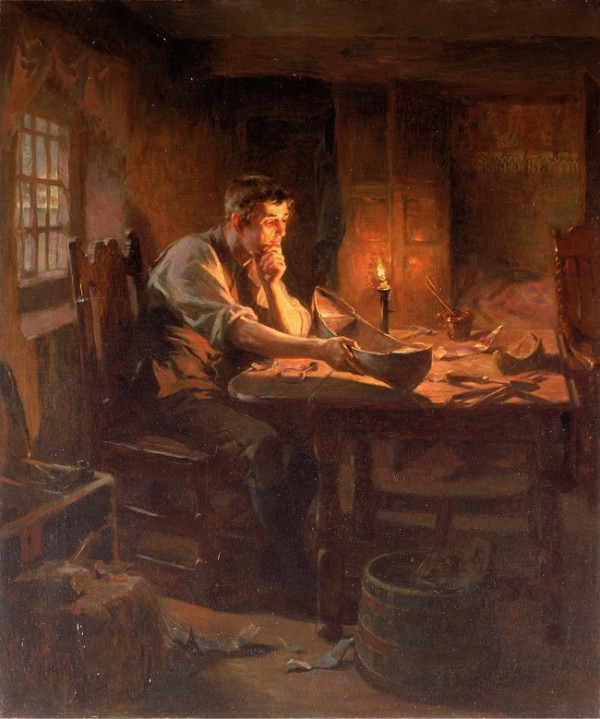

Ralph Hedley (British, 1848–1913), Invention of the Lifeboat, Willie Wouldhave, 1789, 1896. Oil on canvas, 43 x 36 1/4". (© Tyne & Wear Archives & Museums / Bridgeman Images.)

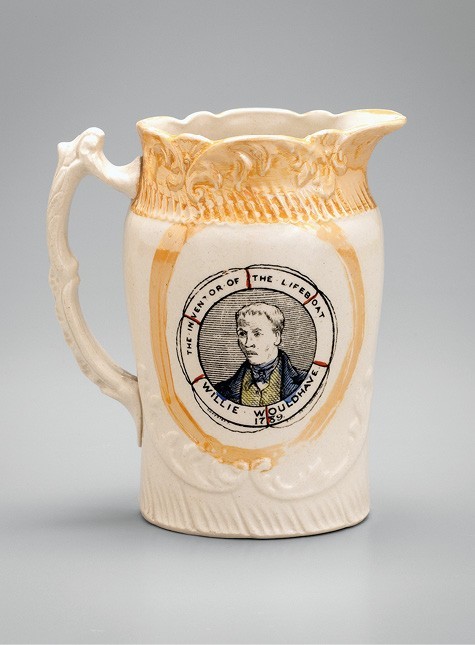

Pitcher, Ball Brothers, Deptford Pottery, Sunderland, England, ca. 1889. Luster-decorated whiteware. H. 6 1/4". Inscribed: “THE FIRST LIFE BOAT WAS BUILT AT / SOUTH SHIELDS. / 1789.” (Collection of the author; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Detail of the reverse of the pitcher illustrated in fig. 2. Inscribed: “THE INVENTOR OF THE LIFEBOAT / WILLIE WOULDHAVE / 1789 / COPYRIGHT OF BALL BROS SUNDERLAND” (Photo, Robert Hunter.)

WILLIAM Shakespeare, The Tempest, act 1, scene 2

O, I have suffer’d

With those that I saw suffer: a brave vessel,

Who had, no doubt, some noble creatures in her,

Dashed all to pieces. O, the cry did knock

Against my very heart.

It is an unfortunate characteristic of human nature that people tend to plan adequately for potential catastrophes only after disaster strikes. Such was the case in 1912 when, just before midnight on April 15, the luxury liner Titanic struck an iceberg in the North Atlantic and began to sink. Those aboard discovered to their horror that the ship carried only enough lifeboats to save fewer than half of the passengers and crew. As a result (and because many of the boats were not filled to capacity), nearly 1,600 souls perished in the frigid waters that night. In the aftermath, maritime officials promulgated new regulations, in effect to this day, requiring passenger ships to carry enough lifeboats to accommodate everyone aboard.

A comparable tragedy occasioned the invention of the lifeboat itself almost a century and a quarter earlier. On March 15, 1789, a crowd watched helplessly from shore as the merchant ship Adventure wrecked in a storm with the loss of all hands near the mouth of the River Tyne off South Shields, County Durham, England. Distressed by the incident, a committee of local citizens offered a reward of two gold guineas to whoever produced the best model for a lifeboat “calculated to brave the dangers of the sea, particularly of broken water.” Two designs were selected as finalists, one by William Wouldhave, a “house painter and teacher of singing,” and another by boatbuilder Henry Greathead.[1]

Wouldhave’s plan featured a self-righting craft inspired by a chance meeting with a woman who requested his help lifting a heavy vessel of water she had drawn from a well. On the surface of the container floated a dipper, a broken section of a wooden bowl. In the course of casual conversation, Wouldhave absentmindedly played with the scoop and noticed that no matter how often he submerged or turned the fragment over, it always righted itself. Based on the same principle, the model he submitted to the committee had a high stem and stern with airtight, cork-filled cases at either end, and righted itself when capsized (fig. 1).[2] Henry Greathead’s model, on the other hand, was “raft-like” and “floated bottom up when intentionally overturned.”[3] Nevertheless, the committee saw fit to grant Wouldhave only half the award and promised Greathead that he would get the contract to construct the first vessel, which he built shortly thereafter.

Thus was born a controversy—apparently still unresolved—over who actually invented the lifeboat. Whoever commissioned the production of a scarce molded whiteware pitcher commemorating the innovation clearly had no doubts, however. The jug features a hand-enameled transfer print on either side. One depicts a small craft being rowed out to a sailing ship in distress during a storm (fig. 2) with the legend “THE FIRST LIFE BOAT WAS BUILT AT / SOUTH SHIELDS. / 1789.” The other displays the portrait bust of a man framed by a life buoy (fig. 3) that is inscribed “THE INVENTOR OF THE LIFEBOAT / WILLIE WOULDHAVE / 1789 / COPYRIGHT OF BALL BROS SUNDERLAND”” Deciphering the barely legible lettering at the bottom of the transfers with the aid of systematic research about potential manufacturers revealed that the pitcher was produced in England by Ball Brothers of Sunderland, a firm that operated from 1884 to 1918.[4] It is likely the piece was commissioned to celebrate the centennial anniversary of Wouldhave’s invention in 1889.

In coming down firmly on the side of Wouldhave, the designer of the pitcher may have been impressed as much by the man’s character as his ingenuity. Indignant over the committee’s decision not to award him the full prize for his design, Wouldhave declined to accept any money at all. When his friends chided him for not taking the guinea offered, he reportedly replied: “Never mind; I know they have sense enough to adopt the good points of my model, and, though I am poor, if they refuse to give me the reward, I shall still have the satisfaction of being instrumental in saving the lives of some of my fellow-creatures.”[5] Thus the pitcher represents an enduring testament not only to a little-known individual’s vital invention but to the humanitarian spirit as well.

Richard Lewis, History of the Life-Boat, and Its Work, 2nd ed. (London: Macmillan and Co., 1874), p. 5.

Major A. J. Dawson, Britain’s Life-Boats: The Story of a Century of Heroic Service (London: Hodder and Stoughton Ltd., 1923), pp. 21–22; Noel T. Methley, The Life-Boat and Its Story (Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott Co.; London: Sidgwick & Jackson Ltd., 1912), pp. 9–10; Lewis, History of the Life-Boat, p. 6.

Methley, Life-Boat and Its Story, p. 51.

Gordon Lang and Ellen Denker, Pottery and Porcelain Marks (London: Miller’s, 1995), p. 288.

Quoted in Dawson, Britain’s Life-Boats, p. 24.