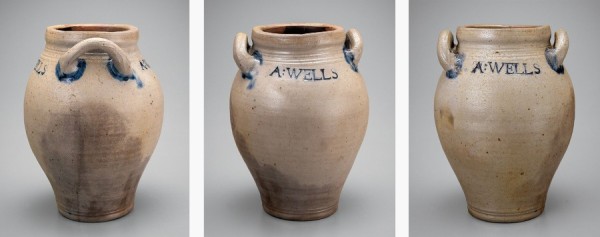

Storage jar, Ashbell Wells, Hartford, Connecticut, ca. 1787–1793. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 10 1/4". (Private collection; photo, Robert Hunter.) This one-gallon ovoid jar displays the impressed mark “A:WELLS” in large block letters on both sides.

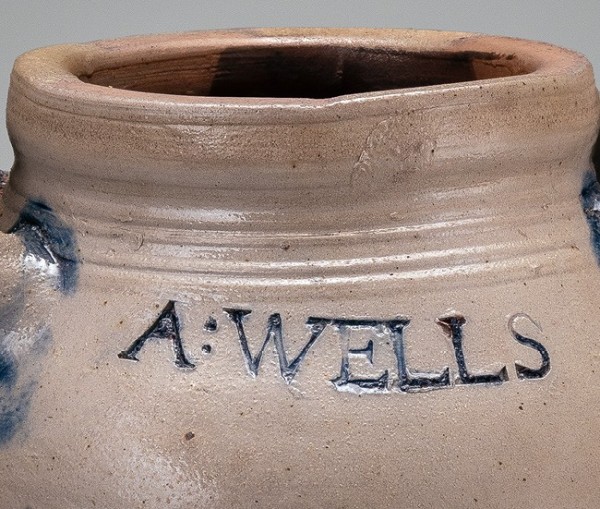

Detail of the mark on the jar illustrated in fig. 1.

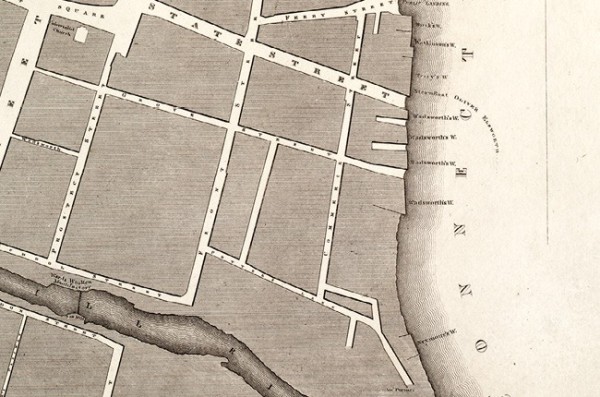

Plan of the city of Hartford, Connecticut, from a survey made in 1824; surveyed and published by Daniel St. John and Nathaniel Goodwin; engraved by Asaph Willard. (Courtesy, Norman B. Leventhal Map Center, Boston Public Library.)

Detail of the map illustrated in fig. 3 showing the suspected location of Ashbel Wells’s property located east of Front Street. Note the name of the street is given as Pottery Lane, although it was also called Potter's Lane.

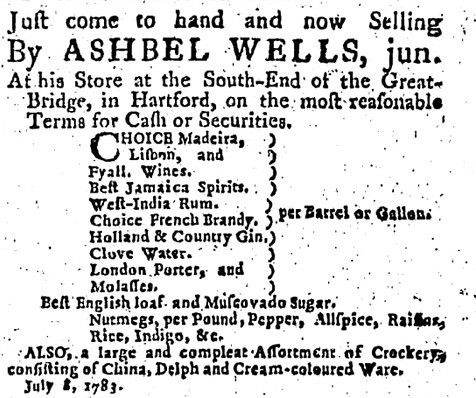

Advertisement published in the Hartford Courant (Hartford, Connecticut), July 8, 1783, p. 2. This is perhaps the earliest indication of Ashbel Wells’s activities as a store owner and ceramics merchant.

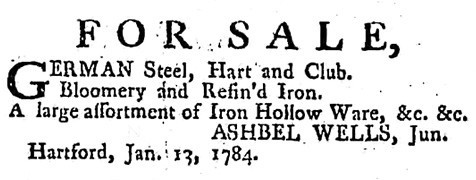

Advertisement from the Hartford Courant, January 20, 1784, p. 4.

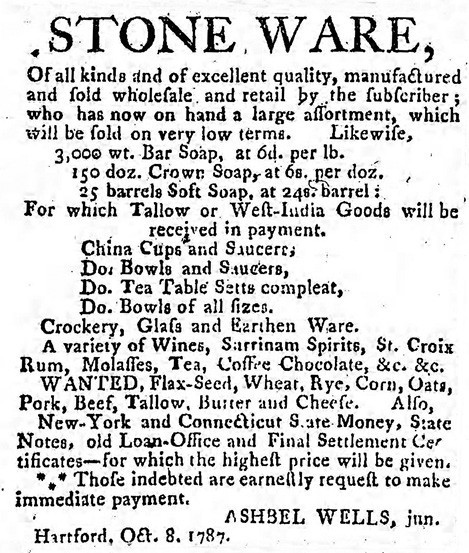

Advertisement from the Hartford Courant, October 22, 1787, p. 1.

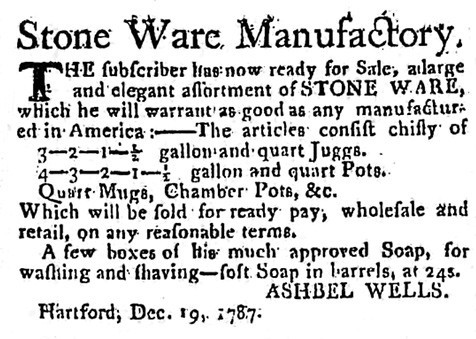

Advertisement from the Hartford Courant, January 7, 1788, p. 3.

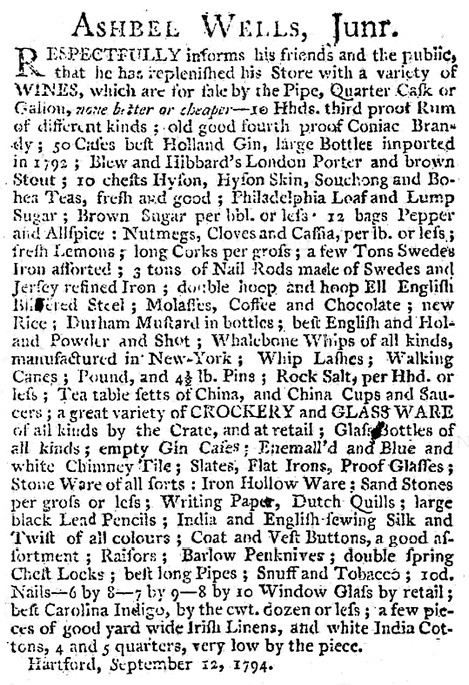

Advertisement from the Hartford Courant, September 15, 1794 p. 2.

Bottom of the jar illustrated in fig. 1 showing a large circular scar resulting from the stacking technique in the kiln.

A detail of the jar illustrated in fig. 1 showing the reddish brown slip used to coat the interior.

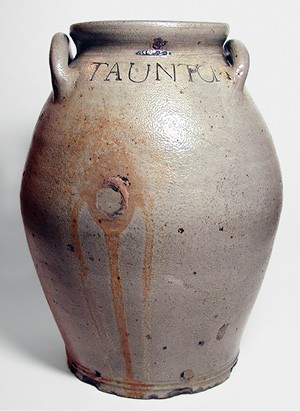

Storage jar, attributed to William Seaver, Taunton, Massachusetts, ca. 1790–1800. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 11 3/4". (Currier Museum of Art, Gift of Lew Sherburne Cutler, 1943.1.38.) This ovoid jar displays the impressed mark “TAUNTON” in large block letters on both sides.

IN 1950 THE PREEMINENT American ceramics historian Lura Woodside Watkins published Early New England Potters and Their Wares after more than fifteen years of intensive documentary research and the physical examination of extant pots and fragments recovered from kiln sites. Although the text contains many unsubstantiated assertions, it remains the de facto reference for students of New England ceramic history and rarely do new objects come to light that are not already framed by Watkins’s encyclopedic treatise. Indeed, her book was my first stop when a previously unseen stoneware jar bearing the impressed mark “A:WELLS” appeared on a social media group (figs. 1, 2).[1]

In her chapter on the eighteenth-century ceramic history of Hartford, Connecticut, Watkins wrote that “the first potter whom I can place by actual date in the city, is Ashbel Wells.” where he is listed as “a trader dealing in stoneware from 1785 to 1794.” While the name had remained a footnote in other ceramics histories since her 1950 publication, certainly no objects bearing Wells’s name or even attributed to his manufactory have been forthcoming.[2]

Watkins’s research identified a deed showing that on April 13, 1787, Wells had purchased from John H. Lord a 60' by 220' lot on the east side of Front Street.[3] She also found a later deed from a quit-claim mortgage made on March 8, 1797, giving up rights to the property which contained a “House, Potters Kiln, Well &c.”[4] This latter document was proof positive for Watkins that Wells operated a stoneware pottery; she went further to profess “a safe presumption . . . that it was he who made and peddled the stoneware.”[5]

The approximate location of that lot is shown on the map in figures 3 and 4. William DeLoss Love’s The Colonial History of Hartford: Gathered from the Original Records (1974) indicates that the property was part of previously undeveloped meadow on the west bank of the Connecticut River.[6]Wells built a brick store there and began to make and sell stoneware. This becomes the origin of the street originally known as Potter’s Lane, now called Potter Street.[7]

In most of the period records, Wells is identified as Ashbel Wells Jr. (or Jun.). He was born into a well-established Hartford family around 1763, son of Ashbel Wells Sr., and in 1783 married Bridget “Britty” Chaucer.[8] From a series of newspaper advertisements placed in the Hartford Courant between 1783 and 1794, we can trace the trajectory of Ashbel Jr.’s entrepreneurial career as a merchant, store owner, and ultimately the owner of a stoneware manufactory.

In 1783, coinciding with the year of his marriage, Wells advertised in the Hartford Courant that his store “at the South-End of the Great Bridge, Hartford” had a large assortment of imported liquors and spirits along with “a large and compleat Assortment of Crockery, consisting of China, Delph and Cream-coloured Ware” (fig. 5). No specific mention is made of utilitarian stoneware, domestic or otherwise, at that time.

Similar advertisements continued for the next several years. Of special note is a series of notices of his supply of “Iron Hollow Ware,” an indication that he was carrying and promoting the regional sources of cast iron, signifying his multifaceted business interests (fig. 6).[9]

On October 22, 1787, the bold words “stone ware” headed his advertisement of various sundries, foodstuffs, grains, and tableware “Of all kinds and of excellent quality, manufactured and sold wholesale and retail by the subscriber” (fig. 7). By this time, about six months after purchasing the property on Front Street, Wells was in the stoneware business.

A more detailed ad (fig. 8) published in the Hartford Courant on January 7, 1788, appeared with the heading “Stone Ware Manufactory.” In it Wells announced that he “has now ready for Sale; a large and elegant assortment of STONE WARE, which he will warrant as good as any manufactured in America.” He further listed “Juggs” in 3 gallon, 2 gallon, 1 gallon, 1/2 gallon, and quart sizes, as well as “Pots” in 4 gallon, 3 gallon, 2 gallon, 1 gallon, 1/2 gallon, and quart sizes. “Quart Mugs, Chamber Pots, &c.” are also mentioned. Similar ads appeared in the Courant for the next several years, but by 1791 less and less emphasis is placed by Wells on stoneware manufacturing.

Based on a reading of the evidence and despite Watkins’s assertion that Wells himself was the potter, his biography indicates little time to have acquired the necessary training. Clearly he was heavily committed to his retail enterprise. Most likely he had made arrangements with a journeyman potter, who was perhaps trained in one of the stoneware potteries in New York or nearby Massachusetts. Teasing out the movements of potters, some of them undocumented immigrants looking to establish themselves in this seminal period of American stoneware production, is fraught with limited information but ample speculation from the collector community.

One possible candidate is John Souter, identified by Watkins as an “English potter.” Watkins referenced the recollections of Hartford resident Albert Risely, who commented in an article in the Hartford Evening Post of March 26, 1883, that Souter “built an earthenware shop on the northeast corner of Potter and Front Streets” sometime around 1790.[10] That location clearly coincides with the same vicinity as Ashbel’s manufactory. Had Souter been Wells’s silent potter/partner all along? Or was he attracted to like-minded manufactures that were beginning to operate on Pottery Lane? We currently have no business records to confirm a connection between Wells and Souter or to refute the timeline or connection.

We do know that at some point in the 1790s Wells appeared to be losing interest in the manufacture of stoneware. In 1792 he bought a substantial dwelling house on Bachelor Street, later named Temple Street. His wife died in 1793, and by September 1794 he had married Mary Hopkins.[11] By 1794 stoneware in his shop inventory was lumped in with the vast quantity of imported ceramics, glass, iron, and other goods (fig. 9). It is tempting to point to the personal upheaval surrounding his first’s wife death as a catalyst for throwing in the towel on running the stoneware manufactory. Watkins speculates that Wells eventually encountered financial difficulties that led to the cessation of the manufactory, certainly a common story among potters throughout history.[12]

Although she does not substantiate the claim, Watkins states that Souter continued potting until he sold the property to Peter Cross in 1805. Cross is better documented as a Hartford stoneware maker who may have continued to work into the 1810s. Research by Brandt Zipp reinforces that Hartford “was clearly a hotbed for stoneware production beginning around 1800. Many, many marks were used as various potters and pottery owners opened new shops, took over each other’s businesses, and struck new, and dissolved old, partnerships with one another.”[13] Whether Souter or Cross was the potter responsible for the marked “A:WELLS” wares will continue to be questioned until new research is unearthed.

Ultimately, it might be the physical clues contained in the newly discovered jar that help identify the maker (fig. 10). The shape and characteristics are similar to other late-eighteenth-/early-nineteenth-century forms seen in Massachusetts, New Jersey, and New York.[14] With its graceful ovoid shape, narrow base, and open horizontal handles, the form recalls classical Greek forms. Cordons around the neck and foot were created with a rib during the throwing. The handles were pulled and attached to the shoulder. With a height of 10 ¼ inches, the capacity is approximately one gallon. In large block letters, “A:WELLS” is impressed on both sides of the jar with what appears to be printer’s type (fig. 11). The lettering was highlighted with cobalt, as were the handle terminals. Like most other New England stoneware manufactories, Ashbel Wells most likely imported the high-firing white clays from the New Jersey South Amboy clay beds.[15] Those clays were transported along the major New England rivers, and Wells’s pottery was located within a few hundred feet of the Connecticut River. The salt-glaze appears well developed.

The interior of the jar was coated with a reddish brown slip prior to firing to create a smooth surface (see fig. 11). This technique of using interior slips is recorded on a number of eighteenth-century fragments from the Crolius and Remmey potteries in Manhattan.[16] A similar technique was developed by the early nineteenth century in Albany, New York, where a dark brown fine clay was used, now formally called Albany slip.[17]

Salt-glazed stoneware was being made in New England beginning in the 1740s and 1750s by Isaac and Grace Parker in Boston, and by Adam Staats and later Abraham Mead in Greenwich, Connecticut.[18] Other stoneware concerns were operating in the late eighteenth century in New London County, centered around Norwich.[19] Watkins identified the stoneware pottery of Christopher Leffingwell and Thomas Williams, dating from the late 1760s and subsequently operated by Charles Lathrop (1792–1796). She also discusses a stoneware pottery started in 1786 by Andrew Tracey and a partner named Huntington. Stoneware fragments recovered from domestic sites of the Mashantucket Pequot tribe in New London County appear very similar to the Wells’s jar form, including the use of a brown interior slip.

The most immediate relationship to any other extant vessel is offered by a tantalizing nugget found in Watkins’s research on stoneware potter -William Seaver of Taunton, Massachusetts. She illustrates and discusses a small stoneware jar (fig. 12) with very similar features but, most compelling, it is impressed “TAUNTON” with block letters around the shoulder of the jar in an identical fashion to the “A:WELLS” jar. Whether this can be attributed to prevailing fashion or a direct connection remains to be seen.

Seaver is known to have been making earthenware in Dorchester, Massachusetts, as early as 1769. However, Watkins states that the first mention of his making stoneware comes from Seaver’s accounts in June 6, 1791, after he moved to Taunton.[20] Watkins also offers that Seaver at some point visited Albany, New York, perhaps to learn the stoneware business. This claim is later repeated by William Bouck in his essay “Early Potters and Potteries in Albany.”[21]

Hartford and Taunton are a little more than a hundred miles apart as the crow flies, and it is possible that Seaver or someone who worked with him had something to do with the Wells stoneware manufactory. We do know that potters moved fairly rapidly between opportunities over even longer distances during this period. For example, Benjamin Duffal, a ca. 1811–1817 stoneware manufacturer in Richmond and other nearby Virginia potteries, relied on potters recruited from New York and New Jersey.[22]

As others have written, by 1800 Hartford, Connecticut, was on the cusp of becoming one of nineteenth-century America’s great stoneware centers.[23] Those later stoneware potters and manufacturers include Peter Cross, Daniel Goodale, Abalom Stedman, as well as the partnerships of George Benton and Levi Stewart, Horace Goodwin and Mack C. -Webster, and Israel Seymour and Stanley Bosworth. Numerous examples of decorated Hartford-made stoneware are considered to be American masterpieces and are included in many museum and private collections. Metaphorically, the “A:WELLS” jar can be recognized as the progenitor to those other stoneware lines, and it is the earliest known New England stoneware vessel with a maker’s name stamped on it.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I thank Mary A. Falvery for her assistance with the historical research for this article, and Chris Pickerell for bringing this jar to my attention.

Lura Woodside Watkins, Early New England Potters and Their Wares (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1950), pp. 193–94.

Richard Miller, “Norwalk (Connecticut) Slip-script Pottery, the Potters, and Related Ware,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2016), pp. 33–57.

Colonial Land Records of Connecticut, 1640–1846: Including Patents, Deeds, and Surveys of Land,” 20:68, warranty deed John Haynes Lord to Ashbel Wells Jr., April 13, 1787, Connecticut State Library, Hartford, Connecticut.

Colonial Land Records of Connecticut, 1640–1846: Including Patents, Deeds, and Surveys of Land,” 20:515, quit-claim mortgage, March 8, 1797, Connecticut State Library, Hartford, Connecticut.

Watkins, Early New England Potters, p. 194.

William DeLoss Love, The Colonial History of Hartford: Gathered from the Original Records (1914; [Chester, Conn.]: Centinel Hill Press, 1974), p. 177.

F. Perry Close, History of Hartford Streets (Hartford, Conn.: Connecticut Historical Society, 1969), p. 177.

https://ancestors.familysearch.org/en/LHZN-YRX/ashbel-wells-jr-1763-1819.

Robert B. Gordon, “Materials for Manufacturing: The Response of the Connecticut Iron Industry to Technological Change and Limited Resources,” Technology and Culture 24, no. 4 (October 1983): 602–34.

Edwin AtLee Barber, Pottery and Porcelain of the United States: An Historical Review of American Ceramic Art from the Earliest Times to the Present Day . . . (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1909), pp. 435–36; Albert Hastings Pitkin, Early American Folk Pottery: Including the History of Bennington Pottery (Bennington, Vt.: Case Lockwood & Brainard, 1918).

Barbara Jean Mathews, The Descendants of Gov. Thomas Welles of Connecticut and His Wife, Alice Tomes, 2nd ed. (Wethersfield, Conn.: Welles Family Association, 2013), p. 783.

Watkins, Early New England Potters, p. 194.

Brandt Zipp, “Some New Info on Peter Cross, Potter of Hartford, CT,” Crocker Farm Magazine (May 7, 2009), https://www.crockerfarm.com/blog/2009/05/some-new-info-on-peter-cross-potter-of-hartford-ct/.

Warren F. Hartmann, “The Stoneware of Early Albany: A Mystery Solved,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2008), pp. 41–66.

Susan H. Myers, “A Survey of Traditional Pottery Manufacture in the Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern United States,” Northeast Historical Archaeology 6, no. 6 (1977): 1–13.

Meta F. Janowitz, “New York City Stonewares from the African Burial Ground,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2008), pp. 41–66.

Paul Cushman, “Paul Cushman: The Premier Albany Potter and His Stoneware,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2012), pp. 155–70.

https://www.sec.state.ma.us/mhc/mhcarchexhibitsonline/parkerharris.htm.

Russell G. Handsman, “New London County (CT) Stonewares and Mashantucket Pequot Pottery from the Late 18th Century” (November 2014), pp. 1–14 (revised version of paper prepared for “Stoneware from Sites in the Northeast.” Session organized for the 2014 meeting of the Conference on Northeast Historical Archaeology, Long Branch, New Jersey), available online at https://www.academia.edu/9476420/New_London_County_CT_Stonewares_and_Mashantucket_Pequot_Pottery_from_the_Late_18th_Century_2014_.

https://siris-libraries.si.edu/ipac20/ipac.jsp?menu=search&aspect=power&profile

=liball&index=UTILEXP&term=7491262.

William Bouck, “Early Potters and Potteries in Albany,” in Paul Cushman: Work and World of an Early Nineteenth-Century Albany Potter (Albany, N.Y.: Albany Institute of History and Art, 2007), pp. 57–68.

Bradford L. Rauschenberg, “ ‘B. DuVal & Co / Richmond’: A Newly Discovered Pottery,” Journal of the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts 4, no. 1 (May 1978): 45–75.

William C. Ketchum Jr., American Stoneware (New York: Henry Holt, 1991), pp. 60–61.