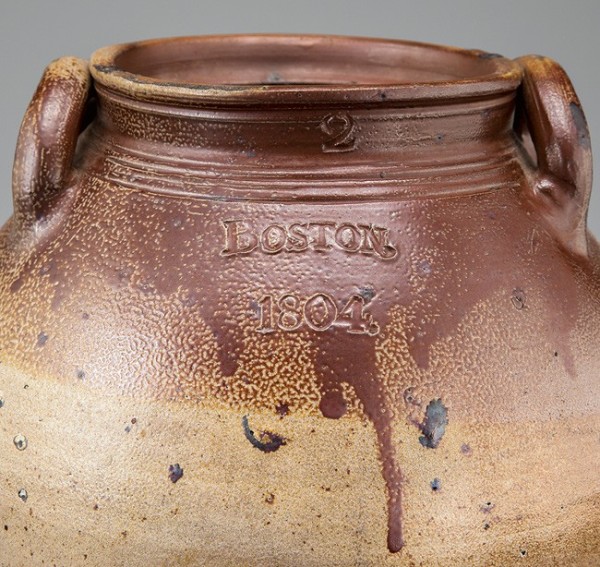

Jar (detail), Frederick Carpenter, Little Pottery, Charlestown, Massachusetts, dated 1804. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 13". Stamped: on neck, “2”; on shoulder, “BOSTON. / 1804.” (The Chapman Collection; photo, Robert Hunter.) This is a detail of the stoneware jar illustrated in fig. 7.

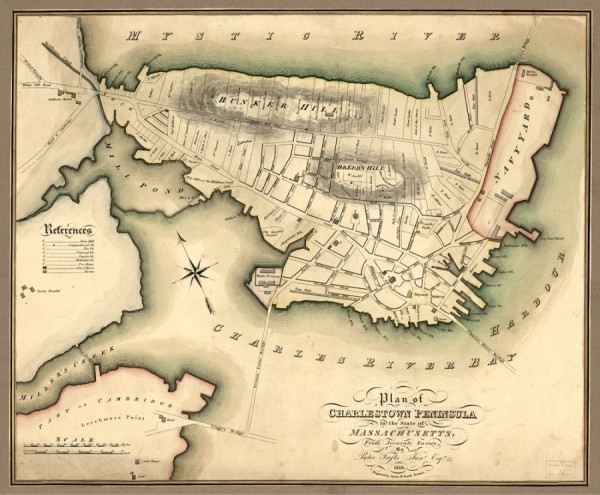

Peter Tufts and Annin & Smith, Plan of Charlestown Peninsula in the State of Massachusetts ([Boston]: s.n, 1818). Hand-colored map, 16 15/16 x 20 7/8". (Library of Congress, www.loc.gov/item /2011589326/.) The property was in the northern part of town on the Medford River, later known as the Mystic River.

Detail of the map illustrated in fig. 2 showing the projected location of the Little Pottery.

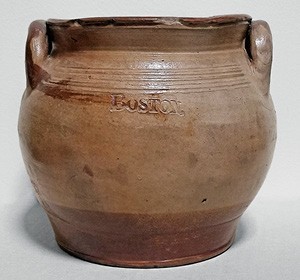

Bean/butter pot, Frederick Carpenter, Little Pottery, Charlestown, Massachusetts, 1801–1811. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 7 3/8". (Ex–Georgiana Greer Collection; photo, courtesy of the author.)

Jar, Frederick Carpenter, Little Pottery, Charlestown, Massachusetts, 1801–1811. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 13 1/8". Stamped: on neck, “2”; on shoulder, “BOSTON.” (Ex–Georgiana Greer Collection; photos, courtesy of the author.)

Jar, Frederick Carpenter, Little Pottery, Charlestown, Massachusetts, 1801–1811. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 16". Stamped: on neck, “3”; on shoulder, “BOSTON.” (Photos, courtesy of the author.)

Jar, Frederick Carpenter, Little Pottery, Charlestown, Massachusetts, 1801–1811. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 16". Stamped: on neck, “3”; on shoulder, “BOSTON.” (Photos, courtesy of the author.)

Jar, Frederick Carpenter, Little Pottery, Charlestown, Massachusetts, dated 1804. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 10". Stamped: on shoulder, “1804. / BOSTON.” (Photo, courtesy of the author.) This example holds one gallon.

Jug, Frederick Carpenter, Little Pottery, Charlestown, Massachusetts, dated 1804. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 16". Stamped, on neck, “BOSTON. / 1804.”; on shoulder, “3” (Courtesy, Crocker Farm, Inc.)

Detail of the swag mark on the jug illustrated in fig. 9.

Jar, Frederick Carpenter, Little Pottery, Charlestown, Massachusetts, dated 1804. Salt-glazed stoneware. Dimensions not recorded. Stamped, on rim, “3”; on reverse, shoulder, “BOSTON. / 1804.” (The Chapman Collection; photos, Robert Hunter.) Three-gallon jar.

Detail of the swag mark on the jar illustrated in fig. 11.

Jar, Frederick Carpenter, Little Brothers Pottery, Charlestown, Massachusetts, dated 1804. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 12". Stamped: on neck, “BOSTON 1804”, on rim: “2” (Private collection; photo courtesy of the author.)

Reverse of the jar illustrated in figure 13.

Jar, Frederick Carpenter, Little Pottery, Charlestown, Massachusetts, dated 1806. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 10". Incised on side, “Mrs Elesebeth Tarbell 1806”; stamped, on shoulder, “BOSTON.” (Courtesy, Adam Weitsman Stoneware Collection; photos, Crocker Farm, Inc.)

Editor’s Note: In the 2019 volume of Ceramics in America, author Lorraine German discussed William Little, a wealthy Boston merchant who was the pivotal force behind the success of the potters Jonathan Fenton and Frederick Carpenter at their Lynn Street pottery in Boston. In this article, she continues the story with the relocation of the pottery to Charlestown, Massachusetts.[1]

THERE HAS BEEN A LOT OF speculation about why the Lynn Street stoneware pottery in Boston closed in 1798. One theory is that the pottery was a financial failure, but this is refuted by the fact that William Little, who had provided the financial backing for the pottery, resumed the manufacture of stoneware in partnership with his brother just two years later (fig. 1).

The answer to the pottery’s fate was found within Boston’s tax records and the personal correspondence between a First Lady and her sisters.

The Rise and Fall of William Little

William Little was a wealthy merchant who was involved in every aspect of Boston’s business and political affairs. As a merchant and shipowner, he shipped goods to and from ports along the Eastern seaboard, as well as the West Indies, Europe, and China. His success as a businessman is evidenced by the fact that the value of his personal estate grew from $600 in 1787 to $10,000 in 1797.[2] His political career began with his election to the board of selectmen in 1791, and in 1796 he was elected to the state legislature.[3] Little’s mansion on Garden Court Street in the northern part of Boston had once been the home of the last colonial governor of Massachusetts.[4]

William Little’s financial and political fortunes came to an abrupt end in 1798, when he became a victim of an economic downturn. Domestically, it had started with the bursting of a land speculation bubble two years earlier. Overseas, American commerce was targeted by French privateers who preyed on American merchant ships during the ongoing hostilities between France and Great Britain.

Merchants in and around Boston paid a steep price for years of poor business habits and easy access to credit. In February 1798 the Massachusetts Mercury printed an article about the high incidence of insolvency among the farmers and tradesmen in New England.[5] The following month, Mary Smith Cranch wrote about the growing number of bankruptcies in the Boston area in a letter to her sister Abigail Adams, the wife of President John Adams.[6]

Three days later, Mary Cranch wrote another letter to her sister, saying “Mr Little one of the representatives of Boston Shut up last week” and many more would soon follow.[7]

William Little’s last advertisement under his own name appeared in the Massachusetts Mercury on March 23, 1798.[8] In May, tax assessors began the first step in Boston’s annual tax-assessment process, visiting each house in every ward to record information about the residents. Little’s record included the information that he was confined. A stark example of his financial situation is shown by the value of his personal estate, which plummeted from $10,000 in 1797 to $0 in 1798.[9] Soon afterward, he lost his bids for reelection to the board of selectmen and the state house.[10]

Financial insolvency among the merchant class was not seen as a personal failing but as a risk one took in the course of doing business.[11] It is likely that, given his social status, Little was confined to his home and not the town gaol. This arrangement was not uncommon for merchants in Massachusetts. Elizabeth Smith Peabody, sister of both Mary Cranch and Abigail Adams, informed the latter that two prominent merchants from Haverhill, Massachusetts, had been confined to their homes because of their debts.[12]

William Little’s inability to provide financial support for the Boston pottery explains its closure in 1798. By May of that year, Frederick Carpenter, who had taken over the pottery after Jonathan Fenton’s departure in 1796, was back in New Haven, Connecticut. Tax records suggest that Benjamin Lukis, a journeyman potter, worked at the pottery after Carpenter left, but the pottery was no longer in operation when the assessment process was completed in October.[13]

Advertisements for Boston-manufactured stoneware continued to appear throughout 1798 and 1799, most likely selling the pottery’s remaining stock. Although no name was given in the advertisements, the address was Little’s store at 46 State Street, now occupied by Israel Munson.[14]

The investments that Little had made in real estate provided him with some of the money he needed to pay his creditors. In March 1798, he sold a house he owned on Greenough’s Lane to Benjamin West for 120 pounds. The following year he sold his home to his brother-in-law John Parker Boyd for $8,970. The Little family continued to live there, taking in boarders to supplement their income.[15]

William Little’s father, who lived in Lebanon, Connecticut, died in May 1798. Later that year or in early 1799, William Little’s brother John arrived from Lebanon. He lived above a shop his brother owned in the North End and worked at the store at 46 State Street.[16] By 1800 John Little had begun advertising under his own name at the State Street address, sharing the premises with Israel Munson.

In September 1800, William Little received nearly $2,000 from his father’s estate, which must have eased his financial problems.[17] Tax records show that his confinement continued through May 1801, but by September he had returned to business, opening a store at 47 State Street.[18] The value of his personal property and income, however, remained $0 through the 1802 assessment period.[19]

William Little’s financial situation improved after his confinement ended. In January 1806 he bought the mansion on Garden Court Street back from his brother-in-law for $12,000.[20] Even though his circumstances improved, however, he never regained the wealth he had enjoyed before his bankruptcy.

The Little Pottery

On July 4, 1800, John Little paid Ebenezer Wait $250 for a piece of land in Charlestown, across the Charles River from Boston (figs. 2, 3). The property was in the northern part of town on the Medford River. John Little built a house on a corner of the property and the remainder was set aside for a pottery.[21] Frederick Carpenter returned from New Haven to set up the pottery, and resumed his job as head workman.[22]

The pottery began production the following spring, and William Little sold the stoneware at his store in Boston.[23] Unlike the Lynn Street pottery, production was not limited to stoneware. Frederick Carpenter also advertised for workers who were skilled in making common earthenware.[24]

Boston Stoneware, Made in Charlestown

Frederick Carpenter’s specialty at the Lynn Street pottery had been jugs and pots decorated in the manner of ocher-dipped English stoneware, and much of the output of the Little Pottery was done in this familiar style (figs. 4–6).

The stoneware was marked “Boston.” It is possible that William Little chose that mark to emphasize the fact that the pottery in Charlestown was a continuation of the earlier Lynn Street pottery, especially to customers outside of the Boston/Charlestown area. Robert Cloutman, a merchant in Salem, Massachusetts, advertised “Stone Ware from the Boston foundery [sic]” and William Imlay announced the arrival of stoneware from Boston at his store in Hartford, Connecticut.[25] And stoneware sherds marked “Boston.” were found at the shipwreck of the Rapid, a Boston ship bound for Canton, China, that sank off the western coast of Australia in 1811.[26]

An unsolved mystery of the Little Pottery is stoneware marked “Boston. / 1804.” (see fig. 1). The fact that the pottery was in operation by 1801 contradicts a theory that the mark promoted the opening of the new pottery. The explanation might be as simple as prideful recognition of a growing town. In March 1804 the Massachusetts legislature voted to annex the six hundred acres of Dorchester Neck to the town of Boston, nearly doubling the town’s size.[27] Boston’s expansion into the sparsely populated peninsula meant more residents, merchants, tradesmen, and manufactures.

While most pieces marked “Boston. / 1804.” were simply dipped in the traditional ocher (figs. 7, 8), some were decorated with cobalt-filled impressed swags, tassels, semicircular bands, three-leaf clusters, or four-lobed rosettes (figs. 9–14).

It is possible that the most ambitious example of stoneware produced at the Little Pottery is a ten-inch-high jar incised with cobalt-filled flowers and a bird and stamped “Boston.” (fig. 15).[28] Written in script are the words “Mrs. Elesebeth Tarbell 1806.” Family history attributes the piece to Nathaniel Tarbell, a member of the Tarbell family of potters in Danvers, Massachusetts, who is said to have given it to his mother as a present.

The Departure of Frederick Carpenter

A notice in a Boston newspaper may provide a clue that the relationship between Frederick Carpenter and his employers had soured by 1810. In October of that year, the following ad appeared in The Repertory: “Any Gentleman wishing to carry on the Stone Pottery business may hear of a good workman who will join him.” Interested parties were instructed to apply at The Repertory’s office.[29]

The use of the word “gentleman” in the ad implies that the workman was looking for someone with the financial means to provide the necessary backing for the venture. Additional evidence is provided by the phrase “Stone Pottery business,” which had been used by Frederick Carpenter in the past when advertising for potters.

If this notice had indeed been placed by Frederick Carpenter, he found the financing he needed in Barnabas Edmands and William Burroughs. Edmands owned a brass foundry in Charlestown and Burroughs, his brother-in-law, was a merchant in Boston. In February 1812 the two men paid James McGee $1,050 for a piece of land along a cove in Charlestown that included the use of a dock on the Charles River.[30]

Burroughs and Carpenter advertised for potters as far away as Hartford, promising liberal wages and guaranteed employment for nine or ten months.[31] In June, Burroughs began advertising stoneware “from a manufactory recently established” at his store on India Wharf, claiming it to be “of the best workmanship” and “the best quality.”[32]

Competing Potteries

The loss of the Littles’ head workman did not signal the end of the Little Pottery. William Little advertised for stoneware and earthenware potters, and in November 1812 he offered stoneware jugs and pickle pots at his new store on Long Wharf.[33] The following month Otis Faye, a merchant at 40 Middle Street, advertised “Earthen Ware, from the different Manufactories of Charlestown, Danvers, &c.” Faye’s shop was in a building that William Little owned, so it is very likely that some of the earthenware came from the Little pottery.[34]

The Little pottery remained active through the first two decades of the nineteenth century, manufacturing both stoneware and earthenware, but documents show that John Little struggled financially during this time.[35] In 1814 he mortgaged his house and his share of the pottery’s property to William. Three years later, he sold his house and his share of the property to his brother Eliphalet, a merchant in New York City.[36] Unfortunately, Eliphalet died immediately after.

The Closure of the Little Pottery

In 1818 President James Monroe nominated William Little to the new position of appraiser of goods for the Port of Boston. Following his appointment, William gave up his merchant’s business and turned his store on Long Wharf over to his brother John.[37]

By the early 1820s, the pottery was in trouble. In May 1821 John Little advertised for a master workman and two or three stoneware turners.[38] Nothing suggests that his search was successful and there are no further stoneware advertisements. When William Bradford advertised stoneware at his Boston store in April 1824, he identified it as coming from “the Charlestown manufactory,” implying that only the Edmands pottery was in production.[39]

John Little’s wife died in 1825 and he returned to Lebanon with his children. In December 1826, he sold his mortgage back to William for $1.[40] William Little died in 1831 and the pottery property remained in the family until William Little’s son-in-law Henry Orne sold it to John Sanborn in 1839.[41]

Lorraine German, “Eighteenth-Century Boston Stoneware: Appealing to a Local Market,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2019), pp. 85–106.

Boston Tax Records, Tax Book Ward 8, 1787, p. 10; Boston Tax Records, Tax Book Ward 3, 1797, p. 11. Courtesy of the Trustees of the Boston Public Library/Rare Books.

“A New Nation Votes.” https://elections.lib.tufts.edu/catalog/LW0205.

“Massachusetts Land Records, 1620–1986,” images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch .org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-L9Z3-QZLF?cc=2106411&wc=MCB5-YTL%3A361613401%2

C362239501), Suffolk, Deeds 1791–1792, vol. 171–173, image 348 of 921; county courthouses and offices, Massachusetts.

“For the Mercury. The Economist, No. IV.” Massachusetts Mercury, February 6, 1798, p. 1.

“Abigail Adams to Mary Smith Cranch, 27 March 1798,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/04-12-02-0246 (original source: The Adams Papers, Adams Family Correspondence, vol. 12, March 1797–April 1798, edited by Sara Martin, C. James Taylor, Neal E. Millikan, Amanda A. Mathews, Hobson Woodward, Sara B. Sikes, Gregg L. Lint, and Sara Georgini [Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2015], pp. 466–69).

“Abigail Adams to Mary Smith Cranch, 14 March 1798,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/04-12-02-0236 (original source: The Adams Papers, Adams Family Correspondence, vol. 12, March 1797–April 1798, edited by Sara Martin, C. James Taylor, Neal E. Millikan, Amanda A. Mathews, Hobson Woodward, Sara B. Sikes, Gregg L. Lint, and Sara Georgini [Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2015], pp. 446–48).

Massachusetts Mercury, March 23, 1798, p. 4.

Boston Tax Records, Tax Book Ward 3, 1798, p. 10. Courtesy of the Trustees of the Boston Public Library/Rare Books.

“A New Nation Votes,” https://elections.lib.tufts.edu/catalog/LW0205.

“Republic of Debtors Bankruptcy in the Age of American Independence,” ABI Journal, April 2003, available online at https://www.abi.org/abi-journal/republic-of-debtors-bankruptcy

-in-the-age-of-american-independence.

“Elizabeth Smith Shaw Peabody to Abigail Adams, 3 July 1797,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/04-12-02-0109 (original source: The Adams Papers, Adams Family Correspondence, vol. 12, March 1797–April 1798, edited by Sara Martin, C. James Taylor, Neal E. Millikan, Amanda A. Mathews, Hobson Woodward, Sara B. Sikes, Gregg L. Lint, and Sara Georgini [Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2015], pp. 183–87).

Boston Tax Records, Taking Book Ward 1, 1798, p. 10. Courtesy of the Trustees of the Boston Public Library/Rare Books.

Yes, October 12, 1799, p. 4.

“Massachusetts Land Records, 1620–1986,” images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch

.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-99Z3-SV47?cc=2106411&wc=MCBR-MWP%3A361613401%2

C362272001 : 22 May 2014), Suffolk, Deeds 1798–1800, vol. 191–193, image 776 of 924; county courthouses and offices, Massachusetts; Boston Tax Records, Transfer Book Ward 3, 1802,

p. 12. Courtesy of the Trustees of the Boston Public Library/Rare Books.

Boston Directory, 1800, p. 71; Russell’s Gazette, June 9, 1800, p. 3.

Ancestry.com, Connecticut, Wills and Probate Records, 1609–1999 (original data: Connecticut County, District and Probate Courts).

Boston Tax Records, Taking Book Ward 3, 1801, p. 1. Courtesy of the Trustees of the Boston Public Library/Rare Books; Boston Commercial Gazette, September 24, 1801, p. 3.

Boston Tax Records, Tax Book Ward 3, 1802, p. 10; Tax Book Ward 3, 1803, p. 10.

Courtesy of the Trustees of the Boston Public Library/Rare Books.

“Massachusetts Land Records, 1620–1986,” images, FamilySearch (https://family

search.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QSQ-G9Z7-P3LR?cc=2106411&wc=MC1M-P66%3A361613501%2C364629701 : 22 May 2014), Middlesex, Deeds 1806–1807, vol. 169, image 6 of 263; county courthouses and offices, Massachusetts; “Massachusetts Land Records, 1620–1986,” images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-L9Z3-9K6R?cc=2106411&wc=MCBR-QNL%3A361613401%2C362304501 : 22 May 2014), Suffolk, Deeds 1805–1806, vol. 214–215, image 192 of 670.

“Massachusetts Land Records, 1620–1986,” images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-99Z7-PSQ6?cc=2106411&wc=MC1M-L3N%3A361613501%2C364610701 : 22 May 2014), Middlesex, Deeds 1800–1801, vol. 139, image 30 of 293; county courthouses and offices, Massachusetts.

Ancestry.com, Massachusetts, Town and Vital Records, 1620–1988.

Boston Commercial Gazette, September 24, 1801, p. 2.

Columbian Centinel, March 14, 1804, p. 3.

Salem Gazette, May 22, 1807, p. 4; Connecticut Courant, November 4, 1807, p. 3; American Mercury, December 24, 1807, p. 4.

Graeme Henderson, Unfinished Voyages: Western Australian Shipwrecks, 1622–1850 (Nedlands: University of Western Australia Press, 1980), pp. 100–101.

“For the Palladium,” New-England Palladium, January 20, 1804, p. 2; The Perpetual Laws of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, Vol. IV (Boston: Thomas & Andrews, 1807), pp. 401, 402.

https://www.crockerfarm.com/stoneware-auction/2021-04-09/lot-1/Highly-Important-Mrs-Elesebeth-Tarbell-1806-BOSTON-Stoneware-Jar/.

The Repertory, October 23, 1810, p. 1.

“Massachusetts Land Records, 1620–1986,” images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org

/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-89Z7-VJ4?cc=2106411&wc=MC1M-RPF%3A361613501%2C364642301 : 22 May 2014), Middlesex, Deeds 1811–1812, vol. 194–96, image 127 of 806; county courthouses and offices, Massachusetts.

Independent Chronicle, February 27, 1812, p. 3; Connecticut Courant, March 25, 1812, p. 4.

Boston Gazette, June 1, 1812, p. 4; New-England Palladium, October 2, 1812, p. 3.

Repertory and General Advertiser, March 6, 1812, p. 3; Repertory and General Advertiser, 10 November 1812, p. 4.

Independent Chronicle, December 21, 1812, p. 3.

Independent Chronicle, April 3, 1815, p. 4; Boston Gazette, May 4, 1815, p. 3; Columbian Centinel, March 7, 1818, p. 4; Columbian Centinel, March 18, 1818, p. 4; Boston Patriot and Daily Chronicle, July 8, 1818, p. 1; Boston Patriot and Daily Chronicle, April 3, 1819, p. 3; P.P.F. DeGrand’s Boston Weekly Report, May 22, 1819, p. 2; Boston Patriot and Daily Mercantile Advertiser, July 21, 1820, p. 1; Columbian Centinel, May 5, 1821, p. 3.

“Massachusetts Land Records, 1620–1986,” images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QSQ-G9Z7-LD8G?cc=2106411&wc=MC1M-PTT%3A361613501%2C364649501 : 22 May 2014), Middlesex, Deeds 1813–1815, vol. 206–8, image 386 of 853; county courthouses and offices, Massachusetts; “Massachusetts Land Records, 1620–1986,” images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-L9Z7-GS2?cc=2106411&wc=MC1M-LNL%3A361613501%2C364658301 : 22 May 2014), Middlesex, Deeds 1817–1818, vol. 221–23, image 29 of 809; county courthouses and offices, Massachusetts.

Journal of the Executive Proceedings of the United States of America, Vol. III (Washington, D.C.: Duff Green, 1828), p. 150; Boston Patriot and Daily Chronicle, July 8, 1818, p. 1.

Columbian Centinel, May 5, 1821, p. 3.

Boston Daily Advertiser, June 5, 1824, p. 3.

“Massachusetts Land Records, 1620–1986,” images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QSQ-G9Z7-KS1L?cc=2106411&wc=MC1M-LN1%3A361613501%2C364689201 : 22 May 2014), Middlesex, Deeds 1826, vol. 269–71, image 701 of 825; county courthouses and offices, Massachusetts.

“Massachusetts Land Records, 1620–1986,” images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QSQ-G9Z7-67XG?cc=2106411&wc=MC1M-YMW%3A361613501%2C364754901 : 22 May 2014), Middlesex, Deeds 1839, vol. 385, image 72 of 300; county courthouses and offices, Massachusetts.