Storage jar, Benjamin DuVal & Co., Richmond, Virginia, 1811–1817. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 15 1/2". (Courtesy, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.) This three-gallon ovoid jar displays the impressed mark “B. DuVal & Co / Richmond.”

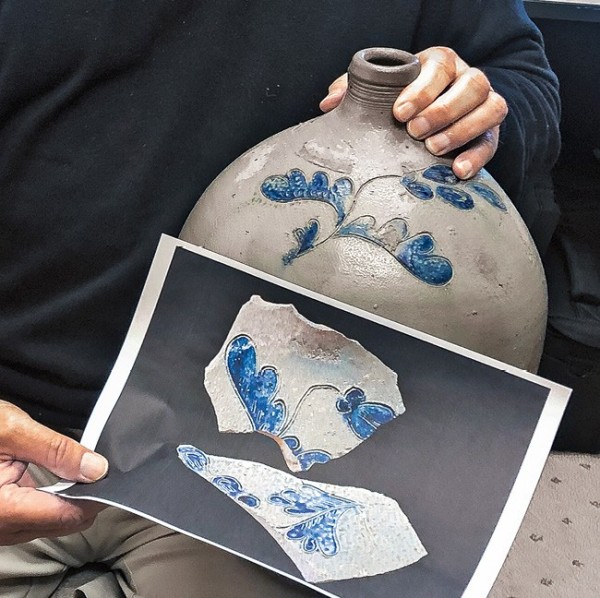

Jar and jug fragments with impressed marks, Benjamin DuVal & Co., Richmond, Virginia, 1811–1817. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Virginia Department of Historic Resources; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Out of the thousands of fragments collected during the DuVal salvage recovery, fewer than a dozen had impressed marks. The historical documentation suggests that the “B. DuVal & Co / Richmond” mark was used from 1811 until 1817, when Benjamin DuVal’s son James took over the operation of the pottery.

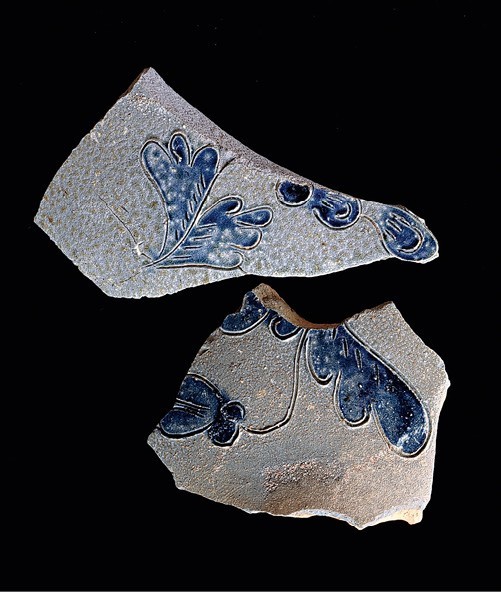

Jar or jug fragments with impressed marks, James DuVal, Richmond Stoneware Manufactory, Richmond, Virginia, 1817–1818. Salt‑glazed stoneware. (Virginia Department of Historic Resources; photo, Robert Hunter.) These marks were recovered in the 2002 salvage project and were attributed to James DuVal’s tenure of the stoneware manufactory after he took it over from his father in 1817. The fragment on the right suggests that the stamps used to create the marks were modular so the different lines could be applied independently.

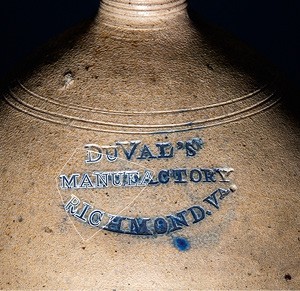

Jug, James DuVal, DuVal’s Manufactory, Richmond, Virginia, 1817–1820. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 17 1/2". Mark, impressed on shoulder: DUVAL’S / MANUFACTORY / RICHMOND, VA. (Courtesy, William C. and Susan S. Mariner Private Foundation; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Detail of the jug illustrated in fig. 4. The impressed mark reads: DUVAL’S / MANUFACTORY / RICHMOND, VA. Note the three incised cordons on the shoulder identical to those shown on the woodcut engraving in fig. 7.

Detail of the jug illustrated in fig. 4 with the fragment illustrated in fig. 3 superimposed over the mark.

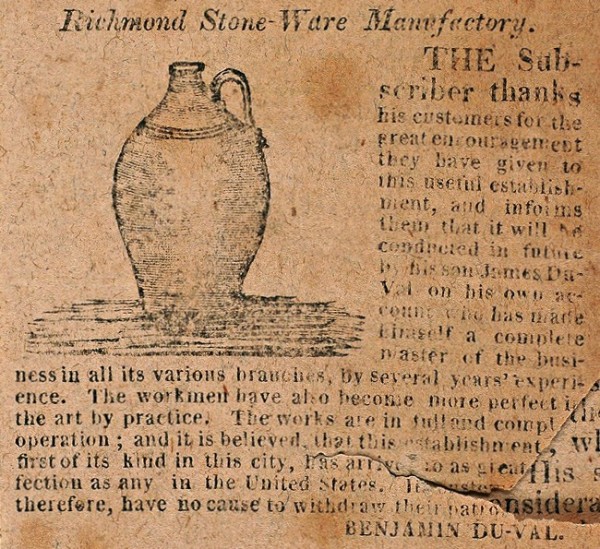

Detail of a newspaper advertisement for the “Richmond Stone-Ware Manufactory,” published in the Richmond Enquirer, May 9, 1817. (Courtesy, Library of Virginia.) Note the depiction of three incised cordons on the shoulder identical to those on the newly discovered jug as seen in figs. 4–6.

Reverse of the jug illustrated in fig. 4. Note the attachment of the handle to the shoulder and the thumb impression on the lower terminus.

A detail of a Benjamin DuVal jug, Richmond Stoneware Manufactory, Richmond, Virginia, 1811–1817. Impressed: “B. DuVal & Co / Richmond” (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Note the attachment of the handle to the neck/lip of the jug and the lack of a thumb impression on the lower terminus.

Jug fragments, Benjamin DuVal & Co., Richmond, Virginia, 1811–1817. Salt-glazed stoneware.

Pitcher, possibly David -Morgan or Crolius Family, Manhattan, New York, ca. 1790–1800. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 12 3/4". (Private collection; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Detail of the incised decoration on the pitcher illustrated in fig. 11.

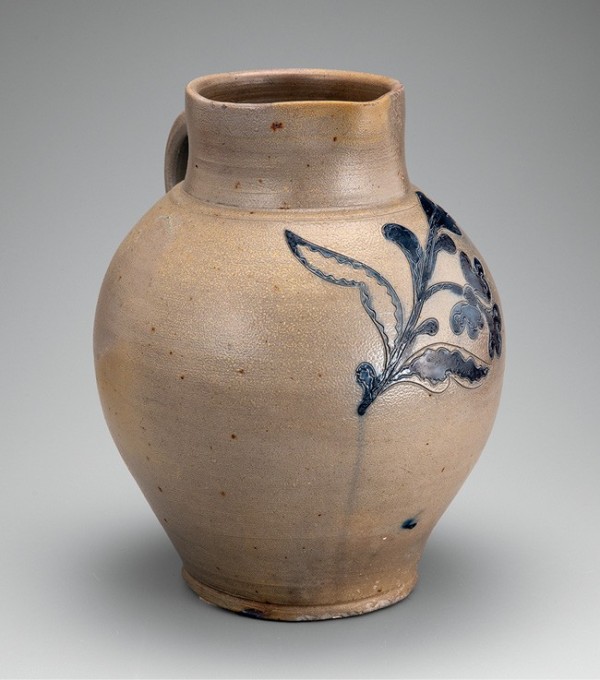

Jug, attributed to Benjamin DuVal, Richmond Stoneware Manufactory, 1811–1817. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 16". (Courtesy, William C. and Susan S. Mariner Private Foundation; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Detail of the incised decoration on the jug illustrated in fig. 13.

The juxtaposition of the fragments shown in fig. 11 with the jug shown in fig. 13. (Photo, Michelle Erickson.)

Detail of the base of the jug illustrated in fig. 13. The base shows a scar—the result of being stacked using a “kiln stacker”—that is identical to the marks seen on the bases of other DuVal vessels.

Reverse of the jug illustrated in fig. 13. Note the attachment of the handle to the neck/lip of the jug and the lack of a thumb impression on the lower terminus.

THE EARLY-NINETEENTH-CENTURY salt-glazed stonewares manufactured by Benjamin DuVal (1765–1826) and his son James (b. 1793) in Richmond, Virginia, are among the best-documented wares of their kind from the American South. This cumulative body of knowledge has been compiled as the result of extensive historical research, several episodes of archaeological recovery on the site before it was destroyed by urban development in 2002, and the study of antique examples that have been published and exhibited over a forty-year period.

Despite the long history of research and documentation of the DuVal stoneware manufactory, many gaps in our understanding have persisted. This short article examines two newly discovered DuVal jugs that further this knowledge exponentially.

The story of the Richmond Stoneware Manufactory was all but lost to ceramics history until 1975, when the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts (MESDA) acquired a large salt-glazed stoneware jar marked “B. DuVal & Co / Richmond” (fig. 1).[1] At that time, MESDA’s research director, Brad Rauschenberg, initiated an extensive records search which brought to light a wealth of documentary evidence, including detailed price lists and descriptions of the available forms.[2]

Benjamin DuVal himself was not a potter but a druggist and multifaceted entrepreneur who hired stoneware potters from New York and New Jersey to produce the wares. His enterprise first produced clay roofing tile as early as 1808, on property north of Richmond’s Main Street between 23rd and 24th Streets. By 1811 he expanded this operation to include the manufacture of salt-glazed stoneware, advertising the entity as “RICHMOND STONEWARE MANUFACTORY, BENJAMIN DU-VAL & CO.” in the August 9 Richmond Enquirer. A number of newspaper advertisements detail the range and variety of vessel forms and sizes which appear to rival those of the best stoneware potteries in Manhattan and New Jersey.

Preliminary artifact collections by Rauschenberg subsequently identified the site and confirmed the survival of its archaeological remnants. The site was also visited by Dr. Norman Barka of the College of William and Mary, where some initial testing resulted in a collection housed at the college. Unfortunately, in 2002 the site was destroyed by commercial development, but during the initial demolition of the property Marshall Goodman and myself led an emergency archaeological salvage effort. We published an illustrated analysis of the vessel forms represented by the several thousand fragments recovered in the 2005 volume of Ceramics in America.[3] Additional information about the DuVal pottery and its relationship to other Richmond and nearby Henrico County stoneware manufactories is summarized in the 2013 volume of Ceramics in America in the article “The Remarkable 19th-Century Stoneware of Virginia’s Lower James River Valley,” which I coauthored with Kurt C. Russ, Oliver Mueller-Heubach, and Marshall Goodman.[4]

We know from the archaeological evidence that a least two different stamped marks were used by the DuVal factory. Based on the MESDA example and another six or seven marked examples, the most common reads “B. DuVal & Co. / Richmond.” The 2002 salvation excavation recovered at least a half-dozen examples of this mark (fig. 2). We know from a single fragment found in 1978 and two fragments found during the 2002 salvation excavation that another variant existed.

The 1978 fragmentary mark contained the impressed letters “Va.” and “Ry” filled with cobalt. At that time, a conjectural drawing was made and Brad Rauschenberg speculated that the mark read “J. DuVal” and/or “Stone-Ware” over “MANUFACTORY / RICHMOND VA.” That would have reflected the change of proprietorship in 1817, when son James DuVal took over the pottery’s operations. One of the two fragmentary marks found in 2002 helps further reveal the entirety of the mark, confirming that the name “DuVal” was part of the stamp (fig. 3, left). At that time we wrote: “The full impressed mark might have read ‘DUVAL STONEWARE MANUFACTORY / RICHMOND VA.’ but no intact vessel with this mark has been found.” That remained true until the summer of 2018, when a three-gallon stoneware jug turned up in an estate sale in Charlottesville, Virginia (fig. 4).[5]

The jug was clearly stamped “DUVAL’S / MANUFACTORY / RICHMOND, VA” and thereby brought to a conclusion any speculation of what the entire mark looked like (figs. 5, 6). The jug itself, though lacking its handle, was nearly identical in form to the one illustrated in Benjamin DuVal’s advertisement in the Richmond Enquirer on May 9, 1817 (fig. 7), in which he announced that the business would be renamed the “Richmond Stone-Ware Manufactory” and “be conducted by his son James DuVal on his own accord.” The DuVals were proud of the form, as they advertised the location of their shop “At the Sign of the Jug.”[6] Intriguingly, this jug has a more elegant, slender form than examples that can be attributed to the earlier 1811–1817 period of production—in particular, both the illustration and the newly identified jug have three incised cordons on the shoulders. And, unlike earlier examples, the jug-handle terminals are different, attaching to the body just below the neck, and the lower terminal has a thumb-pressed indentation (figs. 8, 9). Based on the omission of James DuVal’s name from the 1820 Census of Manufactures, DuVal’s Richmond Stoneware Manufactory is believed to have ceased production by that date.[7]

A more recent discovery of another intact stoneware jug has provided exciting new evidence for the aesthetic oeuvre of this early Southern salt-glaze manufacturer. During the 2002 investigation of the DuVal site, two distinctive fragments were found that immediately stood out from the other thousands that were collected (fig. 10). Both were deeply incised with a floral/leaf design and highlighted with cobalt, and appeared to be from of large jugs. Complementing the bold decoration, the fragments were covered in a highly lustrous salt-glaze that sparkled brightly among the majority of more matte-finished fragments. When they were illustrated in the Ceramics in America article in 2002, we wrote: “These incised fragments were the most enigmatic artifacts found during the DuVal salvage recovery. They suggest very high-quality incised decoration previously unassociated with the DuVal operation or, for that matter, any Richmond-area stoneware.”[8]

Our initial assumption was that these were indications of New York products that had found their way into the mix of artifacts scattered throughout the site (figs. 11, 12). However, lacking any further stylistic evidence or scientific testing of the clay body, in the back of my mind I had hoped they were Richmond-made and had never forgotten them. Nonetheless, I was unprepared when in June 2019 I received a Facebook message from my colleague Brandon Pratt.

Brandon is a stoneware authority in his own right, particularly knowledge-able about the ceramics histories of Alabama, Georgia, and South Carolina. Decorated blue-and-gray salt-glazed stoneware is not within his usual purview, but he obviously recognized the quality and beauty of the jug illustrated in figure 13, which he found in an Atlanta flea market. Brandon knew I always had interest in good American ceramics, and he appropriately assumed that this jug was an early New York–made example, possibly by one of the early Manhattan potters. What he did not know was that he had come across an example from one of my greatest “Antiques Roadshow” daydreams: a skillfully incised example of DuVal’s stoneware, made at the Richmond factory, which was virtually an identical match to the fragments that had challenged me nearly twenty years earlier (fig. 14).

When the jug showed up in my office, I was even more convinced that I was holding a DuVal product. Although I no longer had immediate access to the fragments, a scaled-up photograph juxtaposed on the jug showed corresponding details in the outlines of the leaves and the interior incising details (fig. 15). The jug itself manifested the DuVal characteristic clay color and firing techniques, such as the stacking marks on the bottom and the shoulder (fig. 16). The finish of the neck and attachment points of the now-missing handle suggest that the jug was made during the 1811–1817 period preceding James DuVal’s tenure (fig. 17). In addition, both the bulbous form and the lack of the cordoning seen on the previously discussed jug (see fig. 9) reflect the earlier period of manufacture.

The history of the Richmond Stoneware Manufactory remained veiled for nearly 160 years until the “B. DuVal & Co / Richmond” jar was acquired by MESDA and triggered the research initiated by Brad Rauschenberg in 1975. It took another twenty years for more of DuVal’s secrets to come to light with the salvage excavation of the archaeological remains of the site in downtown Richmond. Despite such voluminous data yielded by that examination, another nearly twenty years passed before these two jugs appeared on the antique market. Even in this age of social media, where incredible amounts are information are shared on a minute-by-minute basis, these two jugs happened to surface at the lowest levels of the antiques circuit, where lifetime accumulations of both trash and treasures are recycled. Fortunately, in both cases two astute students of American ceramics history recognized the importance of these objects and made them available for this documentation. The discovery of these two jugs testify to the fact that it is just a matter of time before the next breakthrough. The search continues. . . .

This three-gallon salt-glazed stoneware jar is illustrated and discussed in the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts online catalog at https://mesda.org/item/collections/jar/1467/.

Bradford L. Rauschenberg, “ ‘B. DuVal & Co / Richmond’: A Newly Discovered Pottery,” Journal of the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts 4, no. 1 (May 1978): 45–75.

Robert Hunter and Marshall Goodman, “The Destruction of the Benjamin DuVal Stoneware Manufactory, Richmond, Virginia,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2005), pp. 37–60.

Kurt C. Russ, Robert Hunter, Oliver Mueller-Heubach, and Marshall Goodman, “The Remarkable 19th-Century Stoneware of Virginia’s Lower James River Valley,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2013), pp. 200–258.

Many thanks to Richmond antiquarian Larry Lindberg for bringing this jug to light, and to Virginia stoneware authority Curtis Rice, who assisted in its acquisition for the present owners.

An advertisement noted the “Richmond Stone Ware Manufactory, at the sign of the Jug.” Richmond Enquirer, May 9, 1817, p. 3.

Rauschenberg, “ ‘B. DuVal & Co / Richmond,’ ” p. 7, n. 41. James DuVal’s death date remains elusive. It is possible that his death led to the closing of the pottery business, but more research is needed to fully understand what happened.

Hunter and Goodman, “Destruction of the Benjamin DuVal Stoneware Manufactory,” p. 56.