Water cooler, Morton & Co., Brantford, Ontario, Canada, ca. 1850–1855. Salt‑glazed stoneware. H. 16 1/2". (Courtesy, Miller & Miller Auctions, Ltd.) Three examples of this cooler are known, all of them with slight differences but all decorated with the same cream glaze and similarly applied figures. One example is at the Royal Ontario Museum.

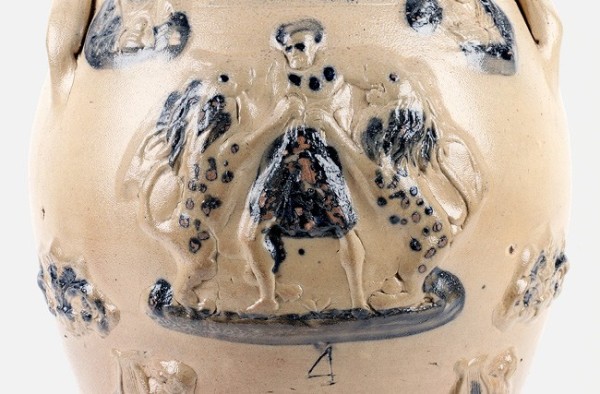

Detail of the molded and applied circus figure (probably the famed American lion tamer Isaac A. Van Amburgh) from the cooler illustrated in fig. 1.

Detail of the impressed mark “MORTON & CO. / BRANTFORD C.W.” on the cooler illustrated in figure 1

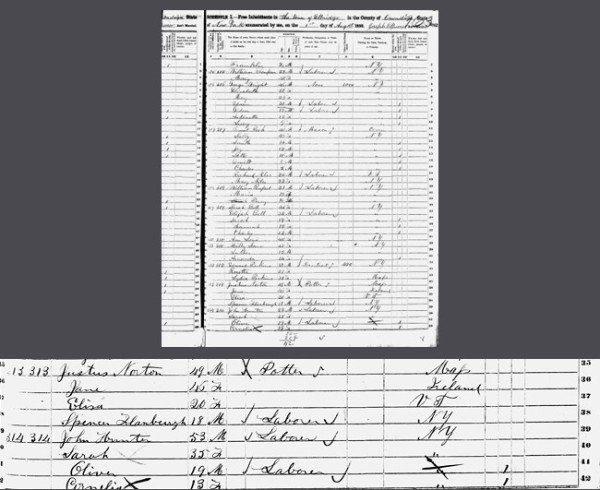

1850 Census, Town of Elbridge, County of Onondaga, New York, showing the name “Justus Norton.”

Teapot, Sanford S. Perry, Whately, Massachusetts, dated 1817. Black‑glazed earthenware. Dimensions not recorded. (Whately Historical Society; photo, Curtis Rice.) This double-handled, double-spouted teapot would have been made when Justus Morton was sixteen years old.

Detail of the bottom of the teapot illustrated in fig. 5 showing the inscribed date of 1817.

Troy from Mount Ida (No. 11 of The Hudson River Portfolio), published by Henry J. Megarey, New York, 1821–1822. Aquatint printed in color with hand-coloring. 14 1/16 x 20 3/16". (Courtesy, Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Edward W. C. Arnold Collection of New York Prints, Maps and Pictures, Bequest of Edward W. C. Arnold, 1954, 54.90.1274[11].) An image of Troy, New York, at the time Justus Morton arrived with Sanford and Julia Perry.

Detail of Map of the City of Albany: With Villages of Greenbush, East Albany & Bath, N.Y. , New York, E. Jacob, C.E., Sprague & Co., Albany, New York, 1857. (Lionel Pincus and Princess Firyal Map Division, New York Public Library Digital Collections.) According to Warren F. Broderick and William Bouck’s Pottery Works, Morton and Church’s 130 State St. address in Albany was near the old burying grounds (circled).

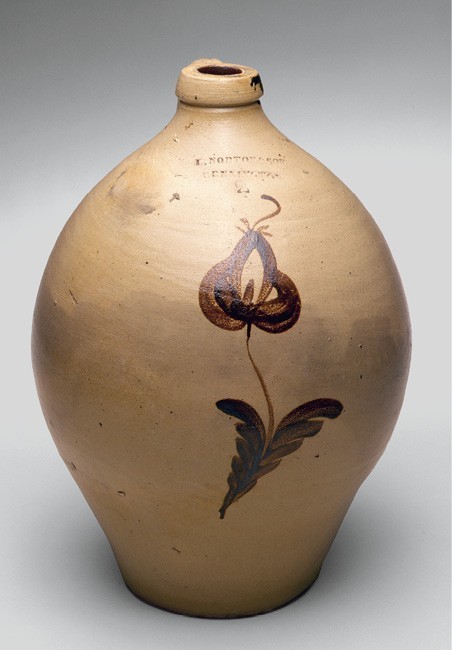

Jug, Luman Norton & Son, Bennington, Vermont, 1828–1833. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 11 3/4". Stamped: l. NORTON / BENNINGTON (Courtesy, Bennington Museum, Gift of John Spargo.) Decorated with a cobalt flower or leaf.

Jug, Luman Norton & Son, Bennington, Vermont, 1833–1840. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 13 3/4". Stamped: l. NORTON & SON / BENNINGTON (Courtesy, Bennington Museum, Gift of John Spargo.) Decorated with an ochre-colored flower

Jug, T. Crafts & Co., Whately, Massachusetts, 1833–1848. Salt-glazed stoneware. Dimensions not recorded. Stamped: T. CRAFTS & CO / WHATELY (Courtesy, Crocker Farm, Inc.)

Jar, S. S. Perry & Co., West Troy, New York, ca. 1833–1835. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 8 1/2". Stamped: SS. PERRY. & CO / WEST TROY (Private collection; photo, Robert Hunter.)

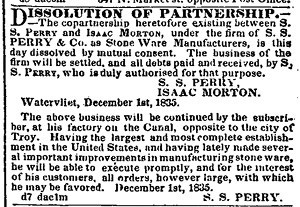

Newspaper notice, Albany Evening Journal, December 15, 1835, p. 3, announcing the end of the Perry/Morton partnership.

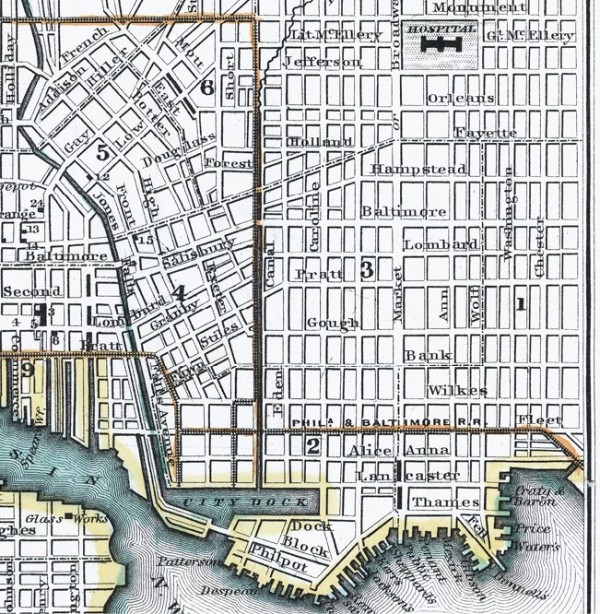

Detail of “Map of Baltimore, No. 26,” from Appleton’s Railroad and Steamboat Companion, Appleton & Co., New York, 1848. (John Hopkins Sheridan Libraries.) This detail shows the area in Baltimore near Eden and Pitt (Fayette) streets where Morton & Brotherton were operating 1840–1841.

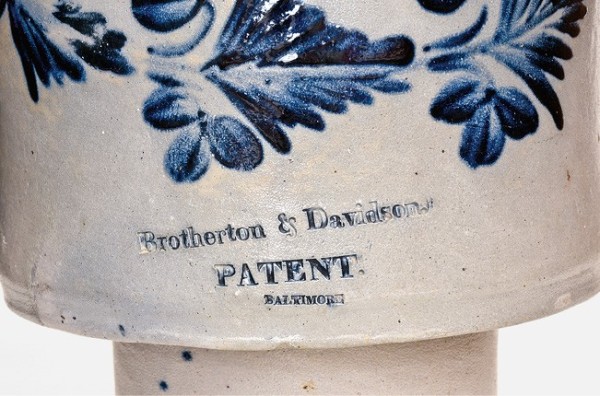

Water filter, Brotherton & Davidson, Baltimore, Maryland, ca. 1838. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 15”. Stamped “Brotherton & Davidson. / PATENT. / BALTIMORE”. (Courtesy, Crocker Farm, Inc.)

Detail of the stamped mark on the water filter illustrated in fig. 15.

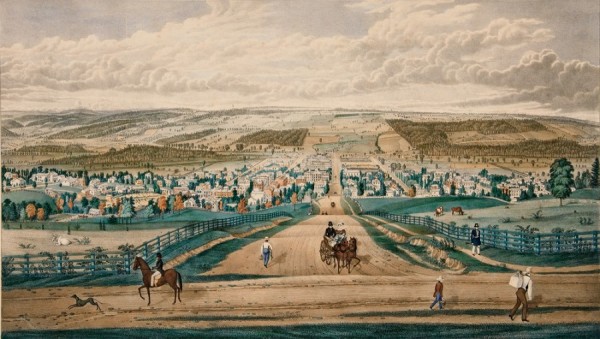

East View of Ithaca, Tompkins County, N.Y., Ithaca, New York, J. H. BuVord’s Lith., Boston, ca. 1836. Colored lithograph on paper. 11 7/16 x 18 1/2". (Mabel Brady Garvan Collection, Yale University Art Gallery, 1946.9.1752.) A view of Ithaca just a few years before Justus Morton’s arrival.

Photo of the Elijah Cornell pottery, on the southwest corner of Lincoln and Lake Streets, in Ithaca, New York, 1975. (Courtesy, Historic Ithaca.) This is the building in which Justus Morton was working in 1842. This photo was taken in 1975, before the building was renovated.

Jug and details, Elijah Cornell, ca. 1842–1850. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 15". Mark: on shoulder, E CORNELL & CO / ITHACA (Courtesy, Sophia Kelly and Ted Sorbel; photo, Sophia Kelly.) This jug exhibits the characteristic muddy-looking clay body of this firm.

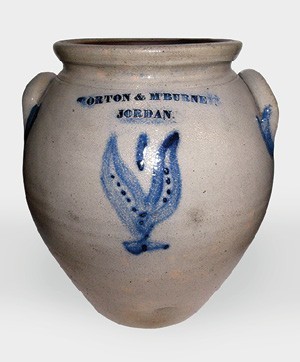

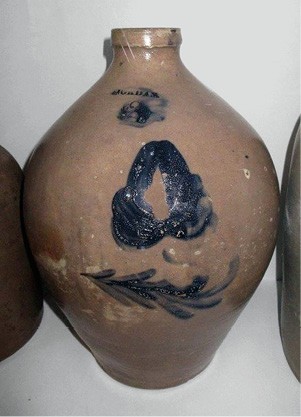

Jar, Morton & McBurney pottery, Jordan, New York, ca. 1848. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 15". Mark: inscribed, on shoulder, MORTON & MCBURNEY / JORDAN. (Jordan Historical Society; photo, Sylvia Lovegren-Petras.) The only McBurney pots to have cobalt on the joins, as far as I know, are the Morton collaborations.

Detail from S. N. Beers, D. G. Beers, A. B. Prindle, F. Bourquin, Stone & Stewart, and Worley & Bracher, Map of Yates Co., New York: From Actual Surveys (Philadelphia: Published by Stone & Stewart, printed by Fred. Bourquin, 1865). (Courtesy, Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2013593242/.) This map shows George Campbell’s place, near J. Mantell and Shem Thomas, two other well-known potters.

Jar, George Campbell and Justus Morton, Penn Yan, New York, ca. 1848. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 12". Stamped: CAMPBELL & MORTON / PENN YAN; inscribed on shoulder, “2” (Courtesy, Bernie and Damian Davis; photo, Bernie Davis.) This two-gallon jar is the first Campbell & Morton piece to be discovered. A second example has recently surfaced and was sold at auction in 2020.

Detail of the jar illustrated in fig. 22.

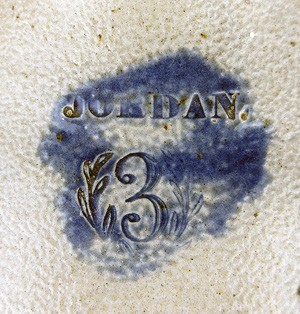

Jug, Justus Morton, Jordan, New York, ca. 1840s. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 15". Stamped: JORDAN. (Author’s collection; photo, Sylvia Lovegren-Petras.) Judging from its shape and markings, this jug may be the earliest known piece of Jordan stoneware. Joins are dabbed with cobalt. The mark has the typical Morton typeface.

Detail of the mark on the jug illustrated in fig. 24.

Jug, Justus Morton, Jordan, New York, ca. 1840s. Salt-glazed stone-

ware. Dimensions not recorded. (Jordan Historical Society; photo, Sylvia Lovegren-Petras.) Ovoid jug marked “Jordan” with Morton’s wreath and typeface, as well as typical “plow flower” cobalt motif.

Jug, Justus Morton, Jordan, New York, ca. 1840s. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 15 1/2". (Author’s collection; photo, Sylvia Lovegren-Petras.) The marked ovoid shape probably puts this one early in 1840s. The hopflower motif was popular with Morton. The jug also shows Morton’s typically casual approach, with a kiln mark right in the middle of the cobalt.

Detail of the jug illustrated in fig. 27 showing the classic Morton wreath and typeface.

Detail of the jug illustrated in fig. 27 showing a typical “whale tail” Morton handle shape.

Jug, Justus Morgan, Jordan, New York, ca. 1840s. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 12 1/2". Stamped: J MORTON (Author’s collection; photo, Sylvia Lovegren-Petras.)

Detail of the J. Morton mark. The laurel wreath surrounding the number 1 is very faint.

Side view of the J. Morton jug illustrated in fig. 30 showing typical use of cobalt to highlight the joins.

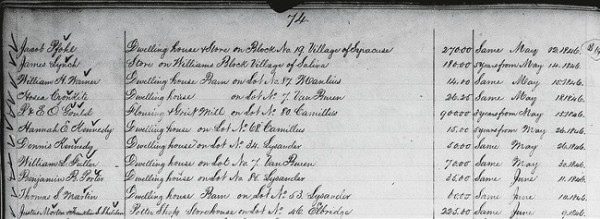

Detail of the Onondaga County Mortgages book, Mortgages 1846–1847, vol. 54–55, image 69 of 644 (familysearch.org.) showing the mortgage of Justus Morton and Franklin S. Sheldon dated June 9, 1846.

Detail from H. H. French and New York State Map and Atlas Survey, Map of Onondaga County, New York: showing military townships and their names, lot lines, numbers, and dimensions, with names of first proprietors . . . location of farm houses and names of owners, and separate plans of the city of Syracuse and all the villages in the county, on a large scale: from official records and new and accurate surveys ([Syracuse, N.Y.]: n.p., 1859). (Courtesy, Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2013593263/.) This map shows where the Morton and Sheldon pottery was on the lot at the southeast corner of Mechanic and Rose Streets, marked here “J. McBurney.” (James McBurney lived and operated a pottery on this lot after Morton left.) There is an Erie Canal feeder stream on the east side of the property.

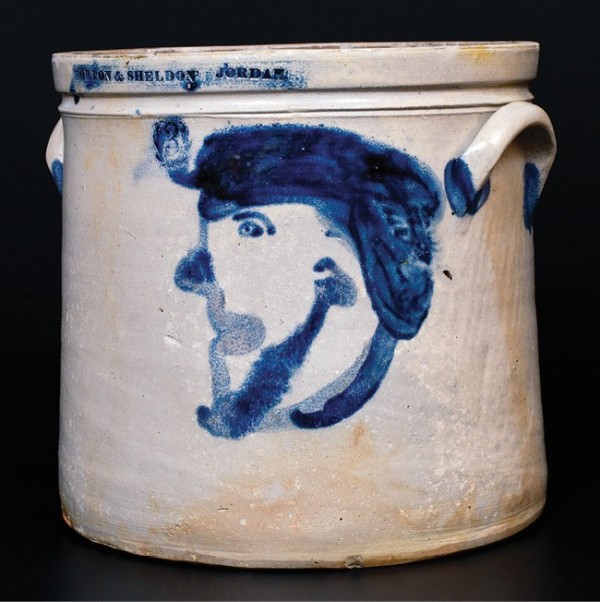

Jar, Justus Morton, Morton & Sheldon, Jordan, New York, ca. 1846. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 10 1/2". Impressed: MORTON & SHELDON JORDAN. (Courtesy, Crocker Farm, Inc.) The inclusion of a man’s portrait is unusual for a Morton product. Could it be a self-portrait of Justus Morton?

Detail of the stoneware jar illustrated in fig. 35

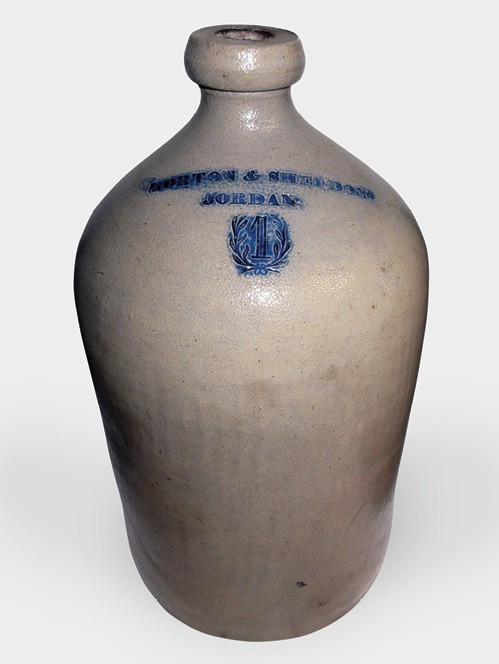

Jug, Justus Morton, Morton & Sheldon pottery, Jordan, New York, ca. 1846. Salt-glazed stoneware. Dimensions not recorded. Impressed: MORTON & SHELDON / JORDAN. (Courtesy, Jordan Historical Society; photo, Sylvia Lovegren-Petras.)

Detail of the jug illustrated in fig. 37 with a clear example of the typeface and the laurel wreath.

Pitcher, attributed to Justus Morton, Lyons, Wayne County, New York, ca. 1845. Albany slip-glazed stoneware. H. 10". (Courtesy, New York State Museum.)

Pitcher, attributed to Justus Morgan, Jordan, New York, ca. 1842–1849. Albany slip stoneware. H. 10". (Courtesy, Crocker Farm, Inc.) Although there is no photograph of the maker’s mark available, I have handled this pitcher (or a twin) and it does bear Morton’s “JORDAN” stamp and is obviously very similar to the Lyons pitcher.

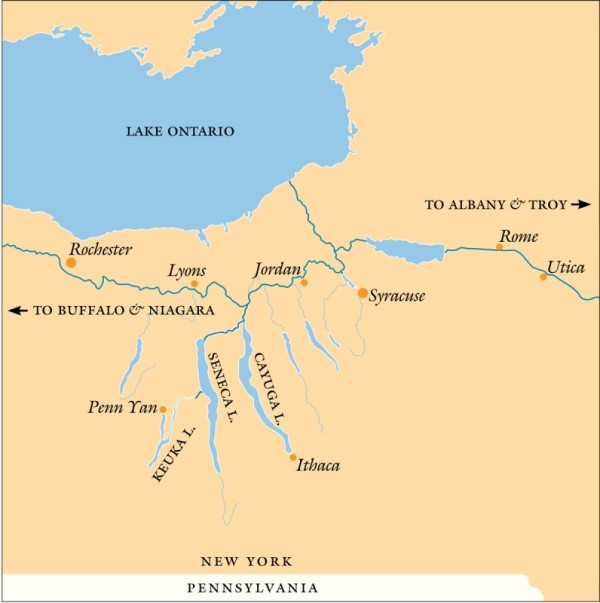

Map of the central New York

canals in the 1840s. (Drawn by Wynne Patterson.)

Edward Lamson Henry, Before the Days of Rapid Transit, 1893. From Charles M. Kurtz, Illustrations from the Art Gallery of the World’s Columbian Exposition (Philadelphia: George Barrie, 1893), p. 301. Hand-colored lithograph. Passengers as well as goods traveled on the Erie Canal in the 1800s. Morton very likely took a packet boat much like this one on some of his trips across upstate New York.

Jug, attributed to Justus Morton, Jordan, New York, 1843–1850. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 12 1/2". (Courtesy, Jennifer and Rich Lung.) This recently discovered unmarked stoneware jug has not only typical central New York cobalt flowers on top but also Baltimore-style horizontal cobalt decoration below. The owners and I believe this to be an unmarked Morton jug.

The unmarked jug illustrated in fig. 43 next to a signed Morton/Jordan jug. (Courtesy, Jennifer and Rich Lung.)

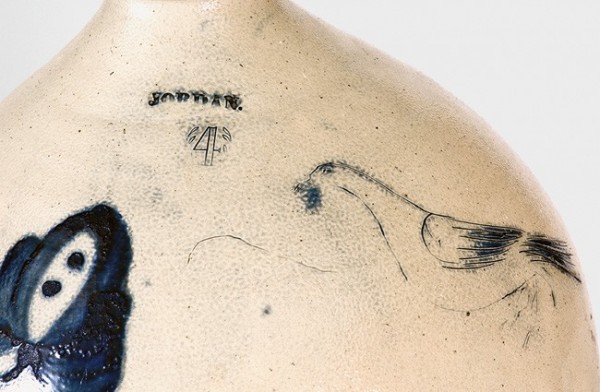

Jug, Justus Morton, Jordan, New York, ca. 1842–1849. Salt-glazed stoneware. Dimensions not recorded. (Courtesy, Crocker Farm, Inc.) Ovoid stoneware jug with cobalt flower with Morton’s characteristic Jordan stamp and wreath around the “4”, with an unusual incised bird on one shoulder and an incised “V” on the other. This is the only known Morton piece featuring a bird and the only known Morton and Jordan piece with incising.

Detail of the jug illustrated in fig. 45 showing the unique incised bird.

Jug, attributed to Justus Morton, Jordan, New York, ca. 1846–1848. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 13". (David Tuxhill collection; photo, Carl Voellings, courtesy Antique Associates at West Townsend.) This jug has the characteristic Morton wreath around the capacity mark. Typically for Morton there is a kiln mark right on the cobalt and some fuzziness to the image. What is not characteristic is the extraordinary scene showing two men firing a canon. There is a good chance the illustration was inspired by the Mexican-American War (1846–1848).

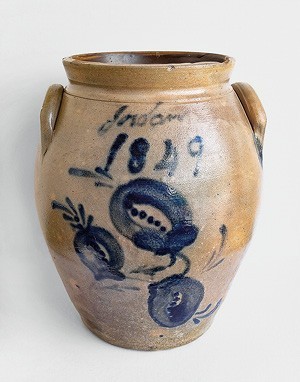

Jar, attributed to Justus Morton, Jordan, New York, 1849. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 13". (Courtesy, Howard Alligood, Arsenal Artifacts.) Unstamped Jordan jar, with some of Morton’s trademark flowers, dated 1849. This object is of particular interest because it establishes that Morton was potting in Jordan when he was supposed to have already moved to Canada.

Jug, Justus Morton, Morton & Co., Brantford, Ontario, Canada, ca. 1854. Salt-glazed stoneware. Dimensions not recorded. (Courtesy, Scott Wallace, Maple Leaf Auctions, mapleleafauctions.com.) Most Morton Brantford ware was decorated with simple flowers, so this face is unusual.

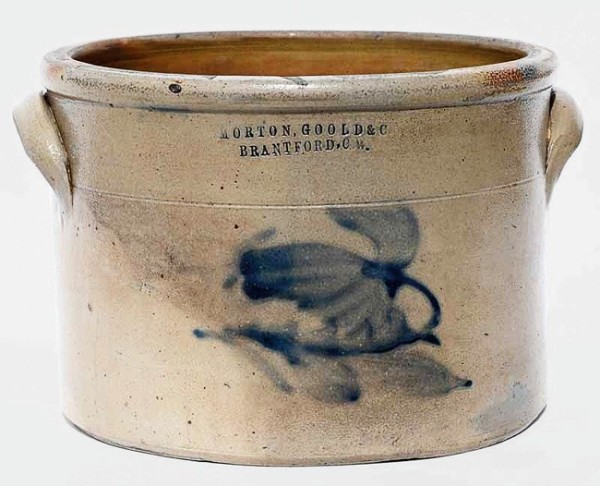

Cake crock, Morton Goold & Co., Brantford, Ontario, Canada, ca. 1859. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 7". Stamped: MORTON, GOOLD & C / BRANTFORD, C.W. (Courtesy, Scott Wallace, Maple Leaf Auctions, mapleleafauctions.com.) This mark was in use for only a few months in 1859 so it is scarce in and of itself, but the small cake crock form is also very unusual for Morton, making it very desirable for Brantford collectors.

BORN AND TRAINED IN AMERICA, potter Justus Morton is paradoxically best known for his work in the Canadian industry. In 1849 he founded the first and certainly one of the largest, most successful stoneware manufactories in Canada West (now Ontario). His Brantford pottery started winning awards almost immediately, and, although Morton ran the company himself for only about eight years, his marked stoneware is still highly sought in Canada: a monumental Morton/Brantford water cooler dating to the early to mid-1850s sold at a recent Ontario auction for CAD$30,680 (figs. 1–3).

In the United States, the story is very different. A search of books on American pottery turns up very little on him, with the exception of one by William Ketchum, who tells us that Justus Morton was an American, born in Massachusetts, who spent some time in the Clark stoneware factory in Lyons, New York, in the 1840s before heading up to Canada in 1849 at age forty-eight.[1] Yet, Morton had been an active potter in the U.S. for at least twenty-five years before he arrived in Canada, where he would work for less than a decade. Why is he celebrated in Canada and so little known in his native land?

Of course many potters were successful and known by their peers even though their names and reputations are unknown to posterity and their wares now unrecognized. But in Morton’s case, it is surprising since he was connected by marriage to a number of very well-known potters, and worked alongside many more in some of the major northeastern American pottery centers. It is even more surprising when one realizes that marked Morton stoneware made in the U.S. is not uncommon.

How did a well-connected, well-known, and prolific American potter—with signed pottery, no less!—slip under the radar so completely? The answer lies almost entirely with the enumerator of the 1850 U.S. census of the Town of Elbridge, Village of Jordan, Onondaga County, New York, who recorded Justus Morton’s last name as “Norton” (fig. 4).

The misdirection of that slip of the pen was compounded by the fact that, while there were no other Mortons in the town of Jordan, there was one Sydney Norton. Researchers erroneously connected “Justus Norton, potter” with this Sydney Norton, although there is no family relationship whatsoever. Justus Morton thereby was erased from the stoneware history books, replaced by “Justus Norton,” who had no antecedents, no history, of whom there is no record of having worked at a pottery or traveled outside Jordan, New York, who paid no taxes, owned no property, and had no family that we know of other than what was listed on the census page. Even those who accepted him as the potter were a bit puzzled by his lack of marked pottery. In his 1987 Potters and Potteries of New York State, 1650–1900, William Ketchum Jr. wrote:

There is, however, also ware marked J. MORTON / JORDAN, and it presents a problem. At first glance the “M” appears only a typographical error . . . for there is no doubt that the name is given as Justus Norton in the census. On the other hand, a potter by the name of Justus Morton worked at Lyons in Wayne County in 1845 and Collard refers . . . to Morton and Company of Brantford, Ontario, “founded at the end of the 1840’s by an American Justus Morton (b. Massachusetts c.1800).” An odd coincidence, indeed, and one that remains unresolved.”[2]

Unlike the elusive Justus Norton, Justus Morton did exist. He had parents, siblings, a wife, and two children, plus he bought property, bought insurance, was named in his father-in-law’s will, filed court papers, took out ads in newspapers, and marked his pottery. But was Justus Norton really this Justus Morton? A comparison of that troublesome 1850 census of Jordan, New York, with that of the 1852 census of Brantford, Canada, is informative:

1850, Jordan, New York[3]

Justus Norton, a potter

Age: 49, born in Massachusetts

Wife: Jane, age 46, born in Ireland

Daughter: Eliza, age 20, born in Vermont

Boarder: Spencer Flanburgh [sic], age 18, born in New York, a laborer

Two years later, the 1852 census of Canada West (Ontario), where Justus Morton was running his successful stoneware factory, Morton & Co., states:

1852, Brantford, Ontario[4]

Justus Morton, a potter

Age: 51, born in Massachusetts

Wife: Jane, age 48, born in Ireland

Boarder: Spencer Flansburgh, age 20, born in New York, a potter

It seems fairly clear that Justus Norton and Justus Morton were the same person.

One other factor links Justus Morton to Jordan, New York. It is something no previous researcher has mentioned and it destroys, I think, any lingering doubts that he, not someone named Justus Norton, was the potter in Jordan. Morton was linked to Jordan through his wife, Jane McBurney, the sister of Jordan stoneware potter James McBurney. James McBurney and Justus Morton were brothers-in-law. They would collaborate in the 1840s, but their relationship was close and went beyond working together as potters for a few years in Jordan. When they were young men, James named his third son (Justus Morton McBurney) in honor of his brother-in-law. After Justus Morton’s death, Morton’s two grieving daughters turned to “Uncle James” McBurney for comfort and counsel.

Because of the confusion between Norton and Morton, Justus Morton’s twenty-five years of work in the United States has been mostly ignored or misattributed. But now that the confusion is cleared up, we can start to look at the long arc of the heretofore unknown life and work of this no-longer-invisible American potter.

A Life of Justus Morton, Potter

Justus Morton was born on April 13, 1801, in Whately, Massachusetts, to Daniel and Sophronia Morton.[5] Daniel, a son of a Revolutionary War veteran,[6] was a brick maker, active from 1782 to 1827. It is probable that Justus and his brothers worked at their father’s brick works, but clay in one form or another seems to have been in Daniel and Sophronia’s children’s blood: two sons became brick makers, two sons became potters, and two daughters married potters.

Whately was an important pottery hub in the early 1800s. Such well-known names as Stephen Orcutt, Luke and Obediah Waits, and Thomas Crafts all got their start in Whately, and Justus and his younger brother Isaac might have apprenticed with them. The Mortons had a close connection with the Crafts family, so it would not have been surprising if Thomas Crafts had taken Justus and Isaac on. Sometime around 1817, potter Sanford S. Perry arrived from Troy, New York, and appears to have worked with Thomas Crafts manufacturing black teapots based on a formula Perry had developed in Troy (figs. 5, 6).[7] It is possible that Justus trained with Perry in this period. In 1821 Justus’s older sister, Julia, married Perry and the newlyweds headed back to Troy, taking twenty-year-old Justus with them.[8]

It is likely that Justus stayed in Troy during 1821–22 working with Perry, possibly for noted stoneware manufacturer Israel Seymour (fig. 7). A number of well-known potters worked at the Seymour factory, among them Perry, Nathan Church Jr. (who was Seymour’s brother-in-law), and William Lundy. Sometime in 1822 or 1823 Justus met and married Jane McBurney in Troy.[9] Their first child was born there in 1824.

Jane and her family had arrived in Troy from Northern Ireland in 1804. Jane’s father, William McBurney, might have been a stoneware potter.[10] In the 1810 U.S. census of Troy, the McBurneys were close neighbors of potter and fellow northern Irish immigrant William Lundy, and the family attended the same church as Israel Seymour.

In 1823 the young Morton family made the first of many moves, relocating across the river to Albany, New York.[11] Justus was listed in the city’s directory as an earthenware maker/baker at “130 State Street, continuation,” near the Lark Street/Washington Square area (fig. 8).[12] In 1824 Nathan Church Jr. arrived from Troy and joined Justus Morton at the 130 State Street address producing stoneware[13] until Church’s death in 1825.[14] Morton continued to operate his pottery/bakery at that address for at least a year after Church died.[15] There are no known examples of Morton’s wares from this period.

The Mortons left Albany in 1826 or 1827. It is possible that Justus went to Athens, New York, to train at Nathan Clark’s factory, as mentioned by Ketchum.[16] By 1828, however, the Mortons had moved to Bennington, Vermont, where second child, Eliza Jane, was born in 1829 or 1830 and where Justus served as a justice of the peace in 1832.[17] It is likely he worked at the pottery there, as his brother Isaac would do fifteen years later. Indeed, there are similarities between Morton’s earliest known works and Bennington pots from this period that go beyond coincidence (figs. 9, 10).

Morton left Vermont in 1833 and appears to have gone back to -Whately for a brief period, perhaps working at Thomas Crafts’s pottery, along with his brother-in-law Caleb Crafts (Thomas’s younger brother), who had married Sophronia Morton a few years earlier (fig. 11).[18] Also in 1833, Sanford S. Perry’s Troy stoneware factory burned down and Perry started a new enterprise in West Troy with his brother-in-law Isaac Morton as his partner. In 1834 Justus Morton and Caleb Crafts headed to West Troy, New York, to work at the family business.[19] Pots produced at that factory bear a striking resemblance to some of Justus Morton’s later wares, and the stamped typefaces are similar (fig. 12). But it seems Justus Morton did not stay long in West Troy, since the Vermont Gazette of October 6, 1835, indicates he was back in Bennington for a few months in 1835. When Perry’s partnership with Isaac Morton terminated at the end of 1835 all four Morton brothers or brothers-in-law left the Troy area for good and dispersed widely (fig. 13).[20] By 1836 Sanford Perry had gone to Virginia, Isaac Morton had relocated to Taunton, Massachusetts, and Caleb Crafts had decamped to Portland, Maine. Justus and Jane Morton went to Baltimore.

The 1837 Baltimore Matchett’s directory lists “Morton, Justus, potter, Washington st. s of Wilk.”[21] The Craig’s and Matchett’s directories for the next few years show Morton at different addresses around Baltimore.[22] By July 1840 Morton was in partnership with Thomas W. Brotherton, who had been in operation at his business on Pitt Street (formerly Parr’s) since 1830 (fig. 14).[23] The partners ran the following advertisement in the Baltimore Pilot and Transcript from July 1840 through January 1841:

The subscribers have associated themselves in co-partnership for the purpose of manufacturing STONE WARE under the firm of BROTHERTON & MORTON, at the old stand, Pitt street, adjoining Harford Run. A large supply will be always kept on hand of a very superior quality. They will still continue to manufacture the PERCOLATING FILTERS, so well known as the best purifiers of water ever invented. They hope by strict attention to business to merit a share of public patronage. T.W. BROTHERTON, JUSTUS MORTON

Brotherton had worked as a potter in Baltimore from 1830 to at least 1842.[24] Beginning in 1837 he was in partnership with a Robert Davidson (who would later go into partnership with James Parr), according to a 1996 report on archaeological mitigation in Baltimore.[25] Although the report shows the Brotherton-Davidson partnership continuing to 1842, it seems clear that Brotherton had ended his partnership with Davidson by 1840 and entered into a new partnership with Justus Morton. So far as I know, there is no surviving Baltimore pottery with Morton’s mark, let alone that of Brotherton & Morton. Recently, however, a Davidson-Brotherton percolating filter appeared at auction, the first known piece with Brotherton’s name (figs. 15, 16). It is likely that any Brotherton & Morton filter would have had a similar shape, if not similar decoration.

Morton left Baltimore in 1842 and turned up in Ithaca, New York, helping Elijah Cornell (who had been making redware) set up his first stone-ware manufactory (figs. 17, 18).[26] Cornell’s son Ezra (who would go on to found Western Union and cofound Cornell University) had been involved in business in the Baltimore area; it is possible that he met Morton in Maryland and arranged for Morton to tutor his father.[27] Morton first appears in Cornell’s journals on July 9, 1842, and their first kiln was fired shortly thereafter.[28] Elijah wrote to Ezra on August 29, 1842:

we have burned a kiln of stoneware and had good luck as we could expect for the first kiln and Morton will likely have another made this week and likewise we have an earthen kiln about glazed and am going to burn this week. . . . I have through Morton advise [sic] wrote to Morgan to know of him as he will let us have a load of clay on credit until spring and then we shall want another load and will make payment for this. . . . PS We want some powder blue that is of a deep coler [sic] as this that we have is very pale.[29]

It is frustrating that Cornell’s journals end in 1842. He did record that Morton owed him $6.28 for three weeks and one day’s room and board for July 1842.[30] In 1844 he wrote to Ezra that Morton had talked to him about Baltimore clay, but the partnership, such as it was, ended in 1844. No records of payments to Morton have survived, so whether Morton was sharing in the profits or was on a salary is not known.[31] Cornell’s stoneware—marked E. Cornell & Co. from 1842 to 1852—is exceedingly scarce (fig. 19). Whether any of the few known pieces were made during Morton’s tenure is difficult to say, although, again, the Cornell stamped typeface is strikingly similar to that used by Morton himself later in the 1840s.

It is very likely that, after the initial setup in Ithaca was done, Morton worked with Cornell either via correspondence or occasional visits, since the Morton family was in Jordan by 1843, ensconced in the bosom of Jane’s family. The Mortons’ eldest daughter, Emily, married to a young man from Penn Yan, gave birth to her first child in Jordan in 1844. And Justus himself filed a court petition in 1845 as “Justus Morton of Jordan, New York,” on behalf of the family of his sister-in-law, Elizabeth McBurney Watkins.[32]

According to reminiscences of a Jordan old-timer, James McBurney and his brother John were coopers in Jordan until Justus Morton arrived to make pottery with his brother-in-law James in the early 1840s, and then Justus and James worked together until the pottery burned in 1849.[33] It is very possible that McBurney’s sons William, Justus, and Harvey—all young teenagers in the mid- to late 1840s and all of whom would go on to become potters—apprenticed with their uncle Justus Morton. The Morton & McBurney mark is quite scarce and the only examples I am aware of are housed in the Jordan Historical Society (fig. 20).

Between 1842 and 1848 Justus Morton was also in Penn Yan, pursuing a partnership with George Campbell (fig. 21).[34] Almost nothing is known about that partnership, and only two jars with the Campbell & Morton mark are known (figs. 22, 23). Daughter Emily Morton’s husband, Michael Waring, was from Penn Yan and in the 1850 census, Emily and Michael are listed as living in Penn Yan next door to Campbell.

With the exception of the two Penn Yan pots, all of Morton’s extant signed American pottery is from Jordan. Currently three marks are known: Morton / Jordan; Morton & McBurney / Jordan; and Morton & Sheldon / Jordan. There are also quite a few pots marked simply “Jordan, New York.” that match the typeface of marked Morton pots (figs. 24–29). Recently a jug marked only “J. Morton” without a place stamp turned up at auction, likely from Jordan but we cannot be certain (figs. 30–32). Precisely when in the period 1842–1850 Morton was producing each of these marks is unclear. We do know that in March 1846, James McBurney sold land to Franklin L. Sheldon and on June 9, 1846, Morton and Franklin L. Sheldon insured a “potter shop and storehouse” on a section of Great Lot 46 on the eastern side of Jordan (figs. 33, 34).[35]

In 2017 Crocker Farm sold an example of Morton & Sheldon stoneware, a short jar or cake crock decorated with an unusual looking man (figs. 35, 36). They dated it 1840–1845 and identified it as having been produced by Franklin Sheldon and Sydney Norton,[36] but the stamp is clearly “Morton” (figs. 37, 38). Sheldon’s 1876 obituary from Auburn, New York, states that he started a manufacturing partnership in that city in 1848, so it is possible his partnership with Morton had ended by 1848, although he was still in Jordan in the 1850 census, working as a laborer—perhaps at the pottery?[37]

To complicate the timeline of Morton’s tenure in Jordan and Penn Yan is Ketchum’s claim that Morton worked for the Clark factory in Lyons, New York, during that period: “Justus Morton, a potter trained at Athens and employed at Lyons until 1848 (when he removed to Brantford, Ontario, Canada, and set up his own stoneware factory), is credited with Albany slip-glazed pitchers with sophisticated sprig decoration. Some of these are stamped LYONS on the base.”[38]

George R. Hamell puts Morton at Lyons in the early 1840s and, like Ketchum, also credits an Albany slip-glazed pitcher made at Lyons to -Morton and it does, indeed, look remarkably like a Morton-marked pitcher produced in Jordan (figs. 39, 40).[39] Given the relative ease of transportation via the Erie and other canals (figs. 41, 42), it is possible that Morton

was shuttling between Lyons, Penn Yan, Ithaca, and Jordan during the 1840s, but it seems impossible that he was solely at Lyons from the early 1840s through 1848. Many details of Morton’s time in central New York need clarification (figs. 43–47).

Although we have no examples of Morton’s wares before his move to central New York, his work there has certain characteristics that might help identify other stoneware:

1. He used the same stamp typeface for all his central New York marks, and it is clearly different from McBurney’s stamp.

2. A laurel wreath surrounds stamped size marks.

3. Often, though not always, cobalt is around the terminals.

4. The potting is experienced but not precise.

5. Any cobalt is often skimpy, pale, and hastily drawn, not the lavish, deep blue, precise designs as found at Fort Edwards or at Burger’s in Rochester. Designs tend to be small or, if large, a bit peculiar. The cobalt often became blurred in firing.

6. He liked molded ware with sprigged decoration, often glazed with Albany slip.

7. Jugs handles are thick and strong, often with a “whale tail” connection. In profile the handles come almost straight off the top of the jug’s mouth, with no rise above the horizontal plane of the mouth.

8. Handles may have shallow ribs or be smooth.

9. The lip is squared off and crisp.

Many of these characteristics carried over into his stoneware in Ontario, particularly his parsimonious use of cobalt and his affection for molded and sprigged wares.

It is no surprise that Morton left New York for Ontario, particularly if the report of the Jordan pottery burning in 1849 is true. He never stayed in one place very long, and the expanding Canadian economy, new railroads, and a new canal in Ontario—combined with a complete lack of stoneware potteries there—undoubtedly drew him.[40] There is some confusion about the date of his move. Records indicate that in 1848 Morton moved to Brant-ford, a town in Brant County, Ontario, and started his factory in 1849. Yet, as we have seen, the 1850 U.S. census shows Justus still in Jordan, New York, working as a potter. At any rate, by 1851 Justus and his wife were definitely in Brantford, and by 1853 he employed six men and produced $8,000 worth of goods per year.[41]

One of the men working at the factory was young Spencer Flansburgh, who had moved with the Mortons from New York. Another was William Richardson, who boarded with the Mortons in Brantford. It is likely that the factory workers included William and Harvey McBurney, both of whom were in Canada in the mid-1850s.[42] It is also likely that Justus McBurney, who left Jordan after 1855, worked for his uncle Justus’s factory: an 1869 newspaper article about him in Iowa mentions his prior renown in Canada.[43] When McBurney married a Canadian girl in Toronto in 1860, William Richardson was one of the witnesses.[44]

The Mortons seemed to do well in Brantford (fig. 49). The factory was prosperous and Justus was elected a trustee at the Brantford Congregational Church.[45] But in 1857 Justus leased the Brantford factory to James Woodyatt and decamped back to the U.S., to Parma, Ohio, near -Cleveland, where he bought a farm for $2,300.[46]

What brought Justus to Ohio is unclear. His brother Erastus was a brick maker in northern Ohio, but we do not know what influence, if any, that had on his decision to move. Whether Justus worked as a potter in Ohio is also unknown. No Ohio pottery with his mark has turned up and, significantly, none of his young protégés appears to have gone to Ohio from Canada with him. Spencer Flansburgh and Harvey McBurney returned to New York, William McBurney went to Detroit, and Justus McBurney stayed in Canada for a time. But whatever Justus Morton’s plans in Ohio had been, they went awry: sometime in 1858 his wife died in Ohio and he returned to Ontario.

In December 1858 Morton entered into partnership with Franklin P. Goold and the Brantford pottery opened again under the name Morton, Goold & Co (fig. 50).[47] On March 16, 1859, Justus, age 57, married 30-year-old Margaret Larlee, a well-off young woman from New Brunswick.[48] But Justus’s plans went awry once again: by summer he knew he was dying of tuberculosis.

He made his will on August 19, 1859, complete with complex instructions on how to keep the pottery running after his death.[49] For reasons unknown, Justus had a change of heart and on August 20 sold the Brantford pottery to Franklin P. Goold and Charles H. Waterous.[50]

Justus Morton died in Brantford early in November. His estate papers do not give the exact date of death, but the bill for the hearse is dated November 6. In his will, he described himself as “Justus Morton, Potter, of Ohio and of Brantford.” He directed that his “beloved” wife, Margaret, be given one-third of his estate, and that his two daughters divide up the remaining two-thirds. And he directed that his body be sent back to Ohio to be buried next to first wife, Jane.[51] He also appointed Thomas Shenston, his friend and Brant county registrar, as his executor.

Shenston would have cause to rue the appointment. As soon as Margaret Larlee Morton had given Shenston the bill for her funeral wardrobe (about $500 in today’s money), she sued to claim the entire estate from Justus’s two daughters, both of whom were in Ohio. Their letters to Shenston—bewildered, angry, and despairing—are preserved in Shenston’s papers at the Ontario Archives. Also preserved is a letter to Shenston from the girls’ uncle, James McBurney, now also living in Ohio—his pottery in Jordan having failed—urging peace between the parties. After four years of wrangling, the estate of Justus Morton was finally settled, with the young widow (now a Mrs. Robinson) and the two daughters each getting one-third.

It is difficult to calculate Justus Morton’s legacy. We do know that his name and his potting skills were passed on, even though his daughters did not marry potters and none of his five grandchildren lived to maturity. Spencer Flansburgh, who moved back to the U.S. after Justus’s death and worked as a potter in Cato, New York, named his son Justus Morton Flansburgh in honor of his mentor.[52] Morton’s nephew, Justus Morton McBurney, would go on to become a successful potter after he left Canada, first in Ohio, then in Iowa. Nephew William McBurney worked as a potter in Detroit and then in Akron, Ohio, and Williams’s sons and grandsons became potters as well, in Ohio and Texas. Nephew Harvey McBurney worked as a potter with T. Harrington in Lyons, New York, and then, along with his son Charles H. McBurney, for John Burger in Rochester for a number of years. Many of the potters who worked and trained at the Brantford pottery learned their craft from Morton and passed that knowledge on to others. None of his work before he started producing stoneware in Penn Yan and Jordan has been identified, so it is difficult to pinpoint his early influences. Surely Thomas Crafts and brothers-in-law Sanford S. Perry and Caleb Crafts were a part of his development as a potter, and perhaps he was part of their development as well. Certainly there is great similarity in their stoneware shapes and designs, and there is no doubt that his time at Bennington influenced his work.

A great deal remains to be learned about this heretofore mostly unacknowledged potter. It is my hope that now that the illusory “Justus Norton” has been dispensed with, the work of the very real and very American potter Justus Morton can at last be examined and appreciated.

William C. Ketchum Jr., Potters and Potteries of New York State, 1650–1900, 2nd ed. (Syracuse, N.Y.: Syracuse University Press, 1987), p. 301.

Ibid.

1850 Census, Elbridge, Onondaga, New York, roll M432_568, p. 382A, image 247.

1851 Census, Brantford, Brant County, Canada West (Ontario), schedule A, roll C_11713, p. 9, line 46. The census planned for 1851 was not carried out until 1852, so it is variously referred to as the 1851 Census and the 1852 Census.

Josiah H. Temple, History of the Town of Whately, Mass., 1660–1871 (Whately, Mass.: T. R. Marvin & Son, 1872), p. 250, available online at https://archive.org/stream/historyoftownof

w00temp_0#page/n13/mode/2up.

James Monroe Crafts, History of the Town of Whately, Mass: Including a Narrative from the First Planting of Hatfield (Orange, Mass.: D. L. Crandall, 1899), p. 522; Temple, History of the Town of Whately, p. 173, available online at https://archive.org/stream/historyoftownof

w00temp_0#page/n13/mode/2up.

Curtis B. Rice, James River Stoneware & The S.S. Perry Connection (Petersburg, Va.: Dietz Press, 2017), pp. 44–45; Lura Woodside Watkins, Early New England Potters and Their Wares (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1950), p. 102; History of the Connecticut Valley in Massachusetts, with Illustrations and Biographical Sketches of Some of Its Prominent Men and Pioneers (Philadelphia: Louis H. Everts, 1879), p. 725.

Henry C. Baldwin, A Guide to Whately Pottery and the Potters: Whately, Massachusetts, 1778 to 1873 ([Northampton, Mass.]: Paradise Copies, 1999).

Crafts, History of the Town of Whately, p. 524.

Ketchum, Potters and Potteries of New York State.

Listed in Klinck’s Albany Directory, for the Year 1823: Containing an Alphabetical List of Residents within the City, and a Variety of Other Interesting Matter (Albany, N.Y.: Printed by E. & E. Hosford, 1823).

Warren F. Broderick and William Bouck, Pottery Works: Potteries of New York State’s Capital District and Upper Hudson Region (Madison, N.J.: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1995), p. 42.

Tobias V. Cuyler, T. V. Cuyler’s Albany Directory for the Year 1824: Containing an Alphabetical List of Residents within the City and a Variety of Other Interesting Matter (Albany, N.Y.: Printed by E. & E. Hosford, 1824).

Will of Nathan Clark Jr., probate date August 5, 1825, Wills, Letters Testamentary, Letters of Administration, Etc., 1787–1902, Albany County (New York). Surrogate’s Office; U.S., Wills and Probate Records, 1659–1999 [database online]. Provo, UT: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2015. (subscription required).

Listed in Ira W. Scott, comp., Ira W. Scott’s Albany Directory, for the Year 1826: Containing an Alphabetical List of Residents within the City, and a Variety of Miscellaneous Matter, for the Benefit of the Public (Albany, N.Y.: Printed by Webster & Wood, 1826).

Ketchum, Potters and Potteries of New York State, p. 368.

Journal of the General Assembly of the State of Vermont, at Their Session Begun and Holden at Montpelier, in the County of Washington, on Thursday 13th October, A. D. 1832 (Danville, Vt.: Eaton, 1832), p. 183, available online at https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=

nyp.33433011265117.

Vermont Gazette, October 22, 1833, available online at https://iw.newsbank.com/apps/readex/docp=EANX&docref=image/v2%3A10380B74B5F0BB28%40EANX119CA120DBA7E138%402390844119CA1214C4FF270%403&origin=image/v2%3A10380B74B5F0BB28%40EANX119CA120DBA7E138%402390844119CA1214C4FF270%403-119CA122C49971C8%40Advertisement (requires registration).

Baldwin, Guide to Whately Pottery and the Potters.

Advertisement, Albany Evening Journal, December 22, 1835, vol. 6, no. 1764, p. 3.

Matchett’s Baltimore Director for 1837–8 (Baltimore, Md.: Baltimore Director Office, 1837), available online at https://archive.org/details/matchettsbaltimo1837balt/page/n51/mode/2up.

Craig’s Business Directory and Baltimore Almanac, originally published Washington, D.C.: R. Farnham, 1842.

John Elliot Kille, “The Cultural Landscape of Baltimore’s 19th-Century Working Class Stoneware Potters,” Ph.D. diss., University of Maryland, College Park, 2009, p. 68.

Ibid.

R. Christopher Goodwin & Associates, “Archeological Mitigation of the J. S. Berry Brick Mill (18BC88) and Pawley Stoneware Kiln (18BC89) Baltimore, Maryland” (December 4, 1996), p. 107.

Sophia E. Kelly, “The Role of Technological Transitions in the Development of American Ceramic Industries: Elijah Cornell and the Shift from Redware to Stoneware Production,” Historical Archaeology 47, no. 4 (2013): 45–70.

Sophia Kelly, “The Potter’s Mark: Redwares and Stonewares Recovered in Excavation of the Duncan-Bower House in the Hamlet of Enfield Falls, New York,” master’s thesis, Cornell University, 2003, p. 84.

Ibid., p. 82.

Ibid., p. 81.

. Ibid., p. 304.

Kelly, “Role of Technological Transitions in the Development of American Ceramic Industries.”

Petition to Cayuga County Surrogate’s Court, 1845, Justus Morton of Jordan, New York, petitioner (photocopy in author’s possession).

Clipping of Rhodes, “T. W. Reminiscenses of Jordan,” Elbridge Citizen, no. 6, ca. 1898 (archives of the Onondaga Historical Association).

Steven B. Leder and Jack McMakin, “Campbell & Morton / Penn Yan: A Newly Discovered Stoneware Manufacturing Partnership,” Maine Antique Digest 37, no. 11 (November 2009): 1.

New York Land Records, 1630–1975, Onondaga, Mortgages, 1846–1847, vol. 54–55, image 69 of 644. Ketchum identified Sheldon as Franklin L. Sheldon, and stated that he left Jordan by 1850 to go to Portage County, Ohio, where he continued working as a potter for many years. I have found a Franklin L. Sheldon who was in Jordan, New York, in the 1840 U.S. census, but no occupations are listed in that census. That same Franklin L. Sheldon and his two children appears in the 1850 Jordan census, working as a laborer (possibly at Morton’s pottery). In 1865 Franklin Sheldon is in Auburn, New York, where he is listed as a manufacturer, and in the 1870 census he is still in Auburn working as an axle manufacturer. He died in Auburn in 1876. I have been unable to find a Franklin Sheldon in Portage County, Ohio, but I have found a Fred Sheldon, who was active as a stoneware potter in Portage County, Ohio, from 1850 until at least 1870 and who appears to have died before the 1880 census was taken. It seems fairly certain that Franklin L. Sheldon of Jordan and Auburn, New York, was Morton’s partner in 1846 and that the purported Ohio connection here does not hold up.

I am not convinced that Sydney Norton of Jordan was actually a potter. According to his obituary, Sydney M. Norton was born in 1799 in Suffield, Connecticut, and in 1827 moved with his family to Jordan, where he opened a fulling mill. He was on the board of the First Presbyterian Church in Jordan, which the McBurneys also attended. He died in an accident while visiting relatives in Michigan in 1847. There is no mention of pottery or potting in his lengthy obituary that appeared in J. Edward Close, Our Church and Her Interests: Being a Souvenir of the Past History and a Survey of the Present and Future Interests of the First Presbyterian Church of Jordan, Onondaga Co., N.Y. (Syracuse, N.Y.: Standard Publishing Co., 1877), pp. 103–4, available online at https://www.familysearch.org/search/catalog/2469607 (requires registration).

“Death of Franklin L. Sheldon,” Auburn Weekly News and Democrat, December 7, 1876.

Ketchum, Potters and Potteries of New York State, 1650–1900, p. 368.

George R. Hamell, “Earthenwares and Salt-Glazed Stonewares of the Rochester-Genesee-

Valley Region: An Overview,” Northeast Historical Archaeology 9 (1980): 10.

Moe Johnson, “Why 1849? The Origins of Stoneware Production in Canada West,” Canadian Antiques & Vintage 37, no. 6 (November–December 2017): 21.

David L. Newlands, Early Ontario Potters: Their Craft and Trade (Toronto: McGraw-Hill Ryerson, 1979), p. 135.

“Potteries of Boone County, History of the Manufacture of Pottery—Quality of Wares,” Montana Standard, November 27, 1869.

Ibid.

Ontario, County Marriage Registers, 1858–1869, York, vol. 84.

History of the Brantford Congregational Church, 1820 to 1920: With Some Account of the Story of the Puritans . . . the Migration of the Family of Mr. John Aston Wilkes to Canada from that Church, 1820 . . . Taken from Original Records by John Robertson [Renfrew, Ont.?: s.n., 1920?: Renfrew Mercury Print), p. 72, available online at http://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.83934/81?r=0&s=1.

Mortgage, Estate of Justus Morton, Shenston Fonds, Archives of Ontario, History of the Brantford Congregational Church, p. 73, available online at http://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.83934/82?r=0&s=1.

Estate of Justus Morton, Shenston Fonds, Archives of Ontario.

Ontario, County Marriage Registers, 1858–1869, Brant, vol. 1.

Will of Justus Morton, Estate of Justus Morton, Shenston Fonds, Archives of Ontario.

Estate of Justus Morton, Shenston Fonds, Archives of Ontario.

I have not been able to locate the graves in the Cleveland, Ohio, area.

Private email correspondence with a descendant of Spencer Flansburgh, June–August 2008.