(Left to right) One-pint mug, one-quart jug, and half-pint mug, Wood & Caldwell, Burslem, Staffordshire, England, 1795–1805. Engine-turned pearlware. H. of mug on left 5". (Unless otherwise noted, all objects and photos are courtesy of Jonathan Rickard.) These three vessels illustrate related slip-filled, engine-turned design elements and the same rouletted bands. The pint mug has a large and clear impressed mark. The jug retains a label from the antiques department of the Boston jewelry store Shreve, Crump & Lowe.

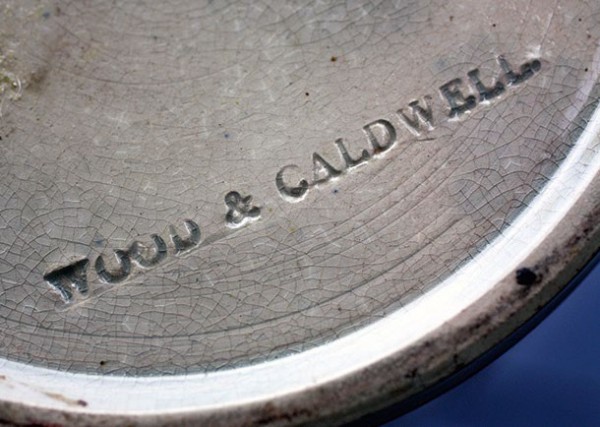

Detail of the impressed mark from the pint mug illustrated in fig. 1 at far left.

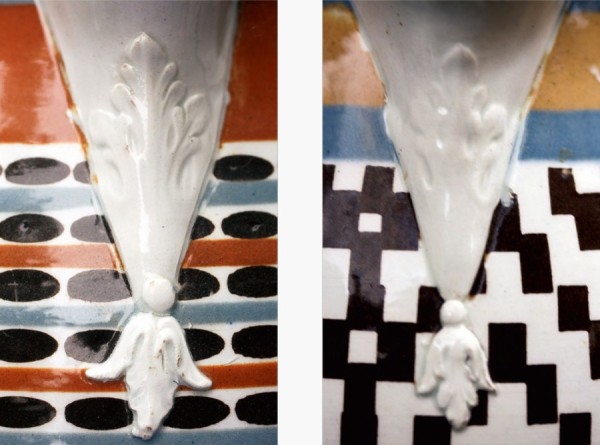

Details of the bottom handle rococo terminals from three related vessels, two of which are illustrated in fig. 1 (left and center).

Detail of the press-molded snip from the quart jug illustrated in fig. 1.

A key fragment from the Burslem waster pit placed on the quart jug illustrated in fig. 1.

An excavated fragment from the site of the Bull’s Head Tavern in Baltimore, Maryland, that relates to the Wood & Caldwell vessels illustrated in fig. 1. (Courtesy, Patricia Samford, Archaeological Conservation Lab, Maryland Department of Planning.)

Punch bowl, attributed to Wood & Caldwell, Burslem, Staffordshire, England, 1795–1805. Engine-turned pearlware. D. 8 3/4". (Carpentier collection.) This punch bowl has lettering formed by impressing metal type characters into the leather-hard clay and filling the resulting depressions with black slip. The repetition of “GOD SAVE THE KING” likely was a toast given at gatherings during the illness of George III.

Detail of the multilevel engine-turned pattern illustrated in fig. 7.

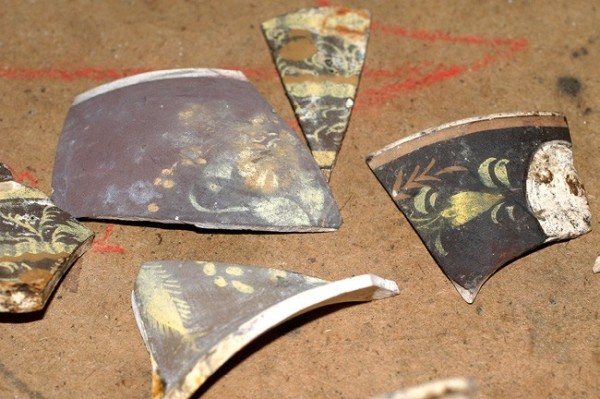

Fragments from an archaeological investigation of the site of a warehouse at the Manchester Dock, Liverpool, England. (Photo courtesy of David Barker.) These examples, along with thousands of others, had been dumped as landfill during the remodeling of the dock between 1807 and 1808. The Staffordshire and other wares destined for export—most likely to the United States—seem to have been unsalable items discarded from one or more of the warehouses in the immediate vicinity of the dock. These fragments related directly to wasters found in Burslem and to archaeological examples in America.

Mug, attributed to Wood & Caldwell, Burslem, Staffordshire, England, 1795–1805. Engine-turned pearlware. H. 6". Leaning against this one-quart mug is a matching biscuit fragment from the Burslem site.

Excavated fragment from the Burslem site with a variation of the pattern on the surviving mug illustrated in fig. 10.

Comparison of the handle terminal from the surviving quart vessel illustrated in fig. 10 (left) and a biscuit waster (right). An advantage of the engine-turning process is the easy modification of mechanical elements to change the design of the turning. Here the subtle pattern change was accomplished by changing the rose cam on the engine-turning lathe.

Mug, attributed to Wood & Caldwell, Burslem, Staffordshire, England, 1795–1805. Engine-turned pearlware. H. 6". This surviving one-quart mug with distinctive handle terminals is shown together with wasters from the Burslem dump site, typical of the bold slip-filled, engine-turned patterns of this group. One atypical waster has a lathe-turned molded foot.

Mug, attributed to Wood & Caldwell, Burslem, Staffordshire, England, 1795–1805. Engine-turned pearlware. H. 4 7/8". This one-pint mug was found in the pantry of a house in South Berwick, Maine, wrapped in 1937 newspaper together with a matching waster from the Burslem dump site. South Berwick borders the Piscataway River upstream from Portsmouth, New Hampshire.

Jug, possibly Wood & Caldwell, Burslem, Staffordshire, England, 1795–1805. Engine-turned pearlware. H. 8 3/4". (Colonial Williamsburg Art Museums.) This large, engine-turned jug has a history of ownership in the Long Island, New York, home of the American poet and editor William Jennings Bryan (1860–1925).

A fragmentary bowl excavated on the grounds of Strawbery Banke in Portsmouth, New Hampshire. (Courtesy, Strawbery Banke Museum.) The engine-turned pattern seen here nearly matches that on the jug illustrated in fig. 15, but is filled with colored slips rather than black. The bowl is nearly identical to the fragment illustrated in fig. 9 that was found in Liverpool.

Jug, possibly Wood & Caldwell, Burslem, Staffordshire, England, 1795–1805. Engine-turned pearlware. H. 8 1/2".

Detail showing the distinctive press-molded snips with attached pendant on the jugs illustrated in figs. 15 and 17.

Detail of the handle terminals on the jugs illustrated in figs. 15 and 17.

Mug, attributed to Wood & Caldwell, Burslem, Staffordshire, England, 1795–1805. Engine-turned pearlware. H. 3 3/4".

Mug, attributed to Wood & Caldwell, Burslem, Staffordshire, England, 1795–1805. Engine-turned slip-decorated redware. H. 4 1/4". This mug with matching pattern and terminals is unusual in that it has a red earthenware body.

Mug, attributed to Wood & Caldwell, Burslem, Staffordshire, England, 1795–1805. Engine-turned pearlware. H. 4 1/4". This half-pint capacity mug has what seems to have been the most popular engine-turned pattern exported to North America.

Pitcher, probably Staffordshire, England, 1795–1805. Engine-turned pearlware. H. 7 3/4". (Collection of Shelburne Museum, gift of Edith C. Blum, 1976-74.27.)

Mug fragment, attributed to Wood & Caldwell, Burslem, Staffordshire, England, 1795–1805. Engine-turned pearlware. H. 4 1/4". This fragment is a waster from the Burslem site.

Mug, attributed to Wood & Caldwell, Burslem, Staffordshire, England, 1795–1805. Engine-turned pearlware. Dimensions not recorded. This quart-capacity mug has vertical engine-turned ribs between colored slip bands

Detail of the handle terminals on the ribbed surface of the mug illustrated in fig. 25.

A surviving one-pint mug with vertical engine-turned ribs similar to the example shown in fig. 25 and related Burslem ceramic wasters.

Mug, attributed Wood & Caldwell, Burslem, Staffordshire, England, 1795–1805. Engine-turned pearlware. H. 4 1/2". The frog figure attached to the inside of the mug might indicate why this mug has the exception of a protruding foot molding.

Basin and ewer, Staffordshire or Yorkshire, England, ca. 1795–1805. Engine-turned pearlware. Dimensions not recorded. This is likely the most heavily produced dipped-ware pattern made not only by Wood & Caldwell but by the Leeds Pottery in Yorkshire, not to mention Wood’s relative John Wood, who worked in Brownfield, Staffordshire, as well as other potters. While blue was by far the most popular color, these sets were produced with other ground colors as well. This ewer and basin is most unusual for its oval basin.

Handle terminal from the ewer illustrated in fig. 29.

A one-pint-capacity blue-dipped mug with related wasters from the Burslem site

A waster from the Burslem site related to the blue-dipped examples illustrated in figs. 29 and 31. It was a universal practice to clear a patch of wet slip in order to provide a secure seal when attaching the handle to a pot.

Dish and cover, attributed to Wood & Caldwell, Burslem, Staffordshire, England, 1795–1805. Engine-turned pearlware. Dimensions not recorded. This pearlware serving dish has a typical Wood & Caldwell acorn knop and was decorated with a veneer of colored-ware shavings from the engine-turning process.

An oval inlaid agate teapot shown with related Burslem biscuit wasters. The teapot is from the Carpentier collection at Eastfield Village.

A biscuit waster of inlaid agate pearlware from the Burslem site.

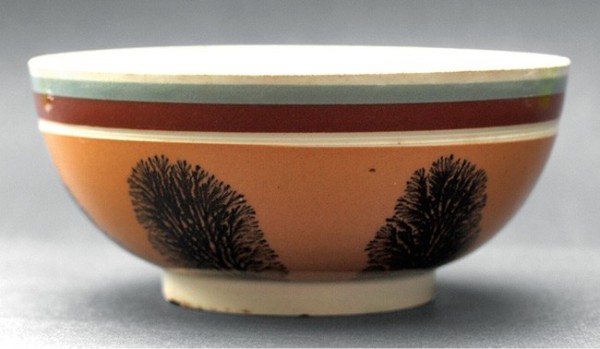

Bowl, attributed to Wood & Caldwell, Burslem, Staffordshire, England, 1795–1805. Pearlware. D. 7". A hemispherical bowl with mocha dendritic decoration and typical color bands touching without intervening space.

Mocha dendritic decoration biscuit wasters from the Burslem site.

Spill vases, attributed to Wood & Caldwell, Burslem, Staffordshire, England, 1795–1805. Encrusted pearlware. H. 7". These vases might have been part of a garniture.

Glazed waster from the Burslem dump site. Note that the textured surface is made from white fragments adhered to the pot surface rather than shavings as seen in those illustrated in fig. 38.

Mug, attributed to Wood & Caldwell, Burslem, Staffordshire, England, 1795–1805. Pearlware. H. 5 7/8". This one-quart pearlware mug has a brown slip ground which is enameled with fioral decoration.

The enameled decoration of these fragments of biscuit wasters survived belowground for about two hundred and twenty years.

An assortment of pearlware glazed and biscuit fragments excavated by Don Carpentier from beneath the tarmac at the unused parking lot of the empty Doulton factory in Burslem, Staffordshire, in 2006.

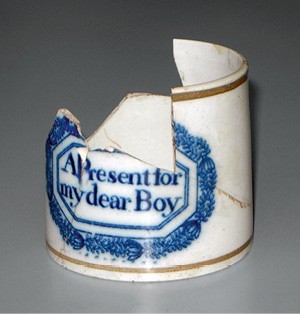

Mug, Burslem, Staffordshire, England, early nineteenth century. Engine-turned pearlware. Dimensions not recorded. This waster, recovered from the Burslem dump site, is from a transfer-printed child’s reward-of-merit mug.

DON CARPENTIER began to construct Eastfield Village in East Nassau, New York, when he was fourteen years old, dismantling late-eighteenth- and early-nineteenth-century buildings within a fifty-mile radius of his father’s east field and reconstructing them on site. Don succumbed to the ravages of ALS in 2014 at age sixty-two. Before dying, he checked that all was well with the historic preservation workshops proceeding in different parts of his much-loved village. Eastfield Village continues to offer seasonal historic preservation workshops and seminars.

JONATHAN RICKARD, an art director and creative director in advertising, lives in Deep River, Connecticut. In 1972 he began to collect dipped wares—slip-decorated creamware and pearlware made in Britain from approximately 1770 through the nineteenth century.

IN 1989 A MUTUAL FRIEND introduced the authors by telephone. Eastfield Village was essentially complete and Don had decided that he wanted to start making dipped wares, fragments of which he kept finding in old house and tavern locations. Within months, Jonathan attended an archaeology conference at Winterthur and met Parks Canada archaeologist Lynne Sussman, who was researching and writing about dipped wares and with whom he’d corresponded.[1] He spent that evening showing slides of his collection to Lynne who, after seeing one particular image, remarked that she knew how that pattern was made, as Don had already made some. Don had taught himself to make lathe-turned earthenware pots the way they had been made in eighteenth-century Staffordshire factories.[2] Within weeks, she and Jonathan met Don at his home in Eastfield Village.

In 2006 Jonathan’s book Mocha and Related Dipped Wares, 1770-1939 was introduced at the New York Ceramics Fair. A month later, Don was again in Staffordshire, where he’d found a waster pit in a trench surrounding the empty parking lot of the closed Doulton factory in Burslem. It had been seven years since Jonathan had suffered sudden paralysis and was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis. Despite his partial recovery, it was too difficult for him to travel with Don as they had done many times, making discoveries of various kinds throughout Great Britain. Don sent images of very distinctive dipped ware wasters that Jonathan was able to match with surviving pots in his collection. “I believe these are all by Wood & Caldwell. How far are you from the Fountain Place site?” Jonathan asked.

Don responded, “I’d say no more than a quarter mile up hill.” More e-mailed images provided additional connections, some outside Jonathan’s collection: wasters that looked like they were from archaeological punch bowls from Alexandria, Virginia; and archaeological examples of bowls and mugs from Strawbery Banke in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, and from beneath the floorboards in an abandoned house not far from Eastfield Village.

On several other trips, Don dug in snow and mud. The trench had been dug with a backhoe to prevent transient groups, known as travelers, from setting up a campground. A chain-link fence added to the preservation along with a guard whom Don got to know. The guard put the backhoe to work, lifting more of the blacktop in order to give Don extended access. Further along the trench Don found clearly different wasters—some with Anthony Shaw’s maker’s mark dating to the 1860–1900 period. Concerned that his collecting of fragments be in compliance with local preservation protections, Don contacted David Barker, then senior archaeologist for the city of Stoke-on-Trent, to make sure his digging did not conflict with any city plans.

Shortly after Don returned from overseas, Jonathan’s pots and Don’s wasters were all spread out on the great granite slab that formed part of the entrance to the reconstructed 1840s meetinghouse at Eastfield. Only one of the surviving examples that Jonathan believed belonged to the group Don had unearthed—a one-pint mug (figs. 1-6)—was marked by an impressed Wood & Caldwell signature. In Don’s collection was a punch bowl, similarly impressed and with a complex engine-turned, multicolored pattern (figs. 7, 8).

Jonathan determined that Don’s wasters were from approximately 1795–1805 (figs. 9-41). Wood & Caldwell operated by that name from 1790 to 1818 during which Enoch Wood (1759–1840) was in partnership with James Caldwell, a financial partner who had no direct involvement with the manufacturing. Caldwell’s involvement set the firm solidly in the rapidly growing export business. On a subsequent visit to Burslem and the waster pit, Don found a penny dated 1799. His finds included more than dipped wares. There were examples of “debased” scratch blue stoneware vessels, painted pearlwares, children’s motto mugs, and pearlware jugs with brown-slip fields on which were painted fioral decoration (figs. 42-43).

In 1818, when Caldwell retired, Enoch Wood continued the business as Enoch Wood & Son, perhaps the most significant exporter of British earthenwares to North America, until the business closed in 1846. The Fountain Place Works was the largest pottery manufacturing facility in Burslem by far. Other Burslem manufacturers of earthenware were smaller, and few had the kind of financial stability to afford expensive engine-turning lathes. John and Richard Riley began their business in Burslem in 1796 and were involved to a lesser degree in export business. Ralph Wedgwood’s Burslem business was bankrupted by 1797. It’s unlikely that this Wedgwood ever employed an engine-turning lathe in his manufacture, although his output included vessels decorated with a veneer of colored clay particles known today as inlaid agate. Examples of that technique are among Don’s wasters. Roger Pomfret has reported that his knowledge of the Rileys’ operation shows no use of such an investment, besides which, as the Riley business grew until 1828, it did so after the most extensive use of engine-turning for decoration had passed, made obsolete by the time and expense necessary to operate such costly equipment during a period of intense competition as wholesale prices were shrinking.[3]

Nearly all of the wasters matching surviving pots in the Rickard collection utilized engine-turning as the major decorative element. Unlike most dipped wares in use in America at this period, these do not have colored glazes over rouletted bands nor do they have a variety of projecting molded base trim. While not all of the handle terminals are identical, most have a characteristic rococo appearance based on silver examples from that period. These design elements are what make the Wood & Caldwell mugs and jugs so distinctive.

A Wood & Caldwell invoice dated June 22, 1797, lists wares being “ship’d by Messrs Rathbone, Hughes & Duncan of Liverpool & consigned to Messrs Cuttler & Amory of Boston on the Account and Risque of Wood & Caldwell of Boston.”[4] Here we have Wood & Caldwell of Burslem sending crates and hogsheads of earthenware over land to Liverpool agents Rathbone, Hughes, and Duncan, who arranged shipping to Boston to agents Cuttler and Amory on behalf of the Boston office of Wood & Caldwell. This was a seriously large and well-funded manufacturing business making the emerging United States one of its principal markets. There is also evidence of the company’s shipping into other ports along the east coast, including Portsmouth, New Hampshire, and Baltimore, Maryland.

Enoch was the son of Aaron Wood, the celebrated block cutter responsible for the molds used to create the outer edge designs for white salt-glazed stoneware plates and dishes. Aaron was the brother of Ralph Wood II, who used the impressed mark “Ra Wood / Burslem” on known examples of inlaid agate creamware. A look at the details—the handle terminals and pendants on snips (pouring lips) of these ca. 1800 wasters—shows the quality of these wares and the suggestion of the availability of precise, well-designed block molds. Over several generations the Wood family was intertwined, through business connections and marriage, with the Wedgwood family, adding yet another distinction to their business output.[5]

Lynne Sussman, Mocha, Banded, Cat’s Eye, and Other Factory-Made Slipware (Boston: Council for Northeast Historical Archaeology, 1997).

Jonathan Rickard and Don Carpentier, “The Little Engine that Could: Adaptation of the Engine-Turning Lathe in the Pottery Industry,” Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2004), pp. 78–99.

Roger Pomfret, “John and Richard Riley, China and Earthenware Manufacturers,” Journal of Ceramic History 13 (1988): 1–27.

A copy is in the Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera at the Henry Francis du Pont Winterthur Museum in Delaware.

Frank Falkner, The Wood Family of Burslem (1912; Wakefield, Eng.: E. P. Publishing, 1972).