Thomas Jefferson’s rotating Windsor armchair. Courtesy, American Philosophical Society.

F24-10 and F24-12

F24-11

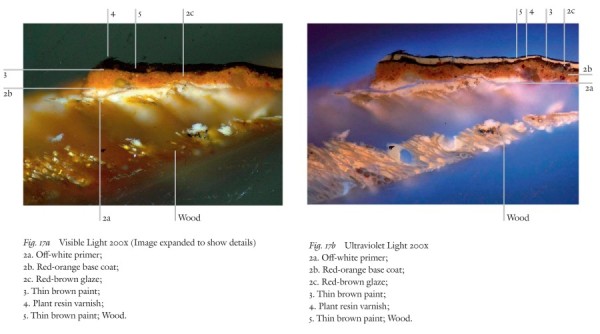

F24-13

F24-14

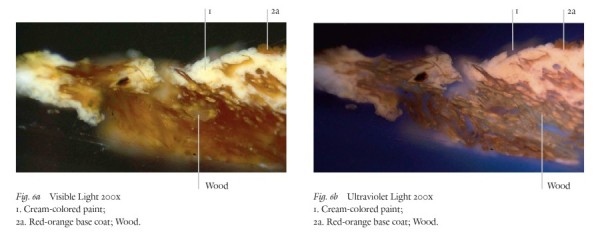

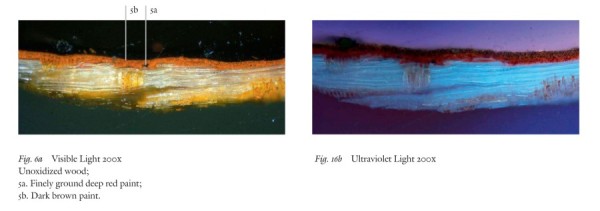

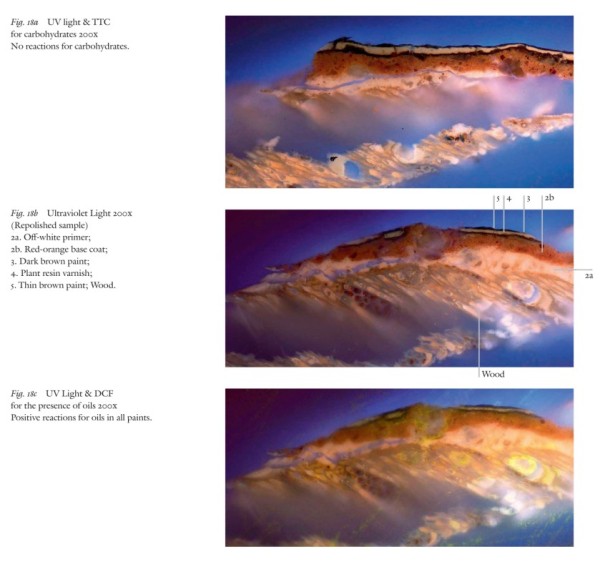

Figure 6a-b F24-11. Chair seat, PL side of seat near front, below incised line, near spot of bronze powder paint.

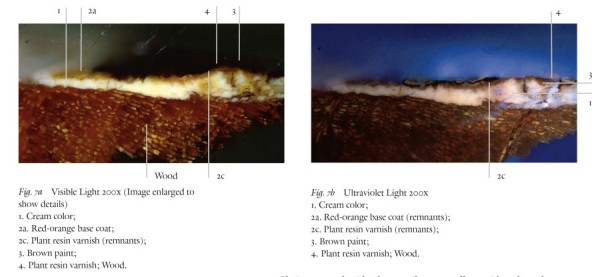

F24-12. Chair seat, side of PR arm, just in front of iron strap.

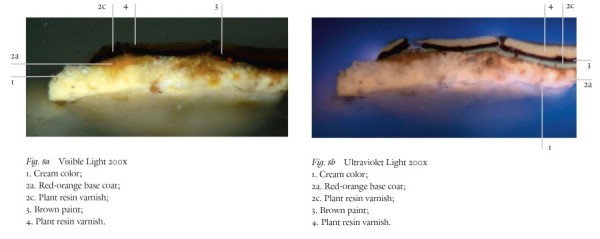

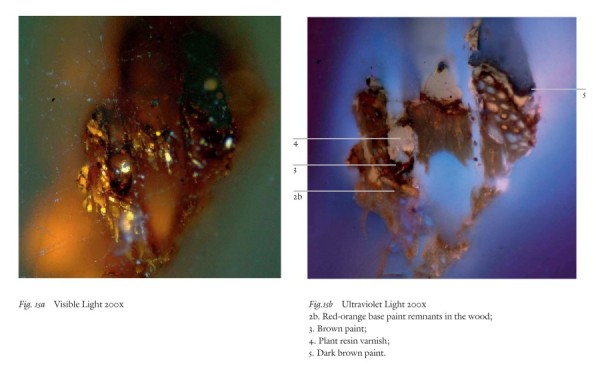

F24-13. Chair seat, underside of crest rail, near scroll, PR side at large loss area.

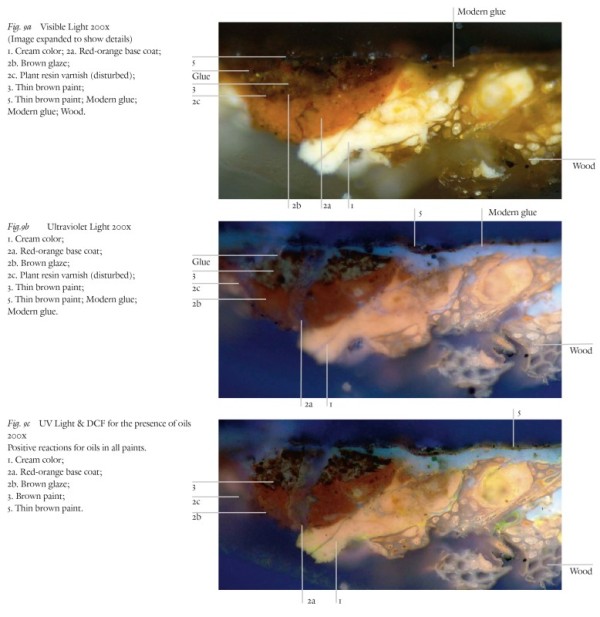

F24-14. Chair seat, top of seat, adjacent to spindle at rear.

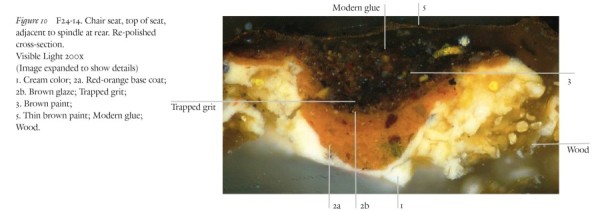

F24-14. Chair seat, top of seat, adjacent to spindle at rear. Re-polished cross‑section. Visible Light 200x (Image expanded to show details)

1. Cream color; 2a. Red-orange base coat;

2b. Brown glaze; Trapped grit;

3. Brown paint;

5. Thin brown paint; Modern glue;

Wood.

F24-1

F24-2

F24-3

F24-14

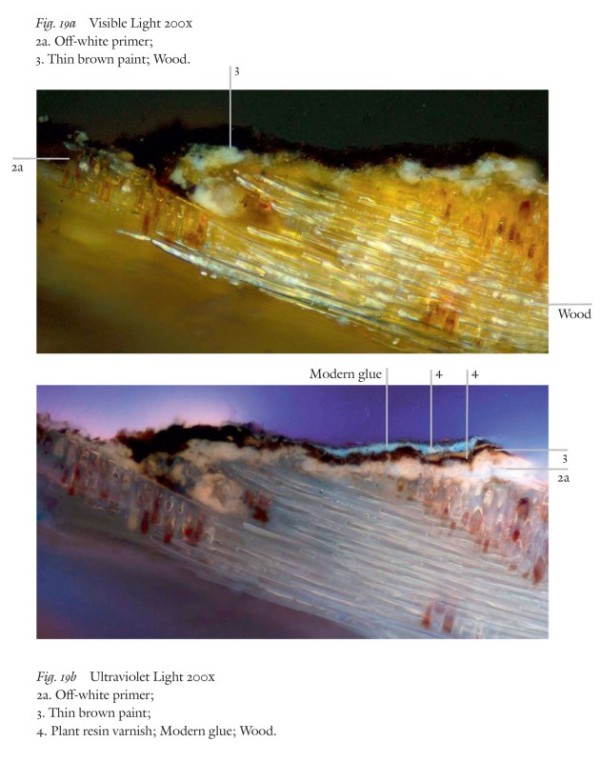

F24-1. Base, top edge of base for turned seat mechanism.

F24-2. Base, top edge, front Proper Left (PL) leg.

F24-3. Base, at join with central stretcher with PL side stretcher.

F24-3. Base, at join with central stretcher with PL side stretcher.

Visible Light 200x

2a. OV-white primer;

3. Thin brown paint; Wood.

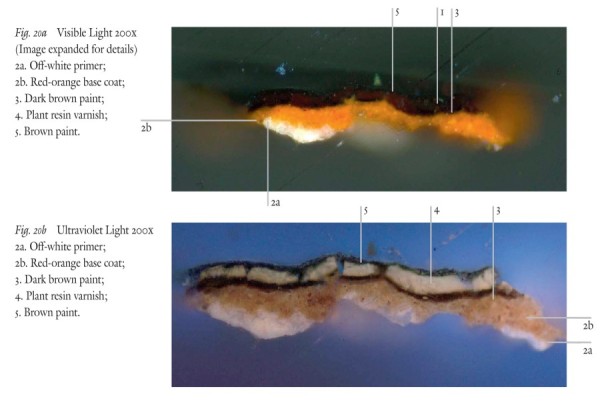

F24-5. Base, PL side leg, in bottom bamboo turning near join with stretcher.

F24-6 and F24-7

F24-8

F24-9

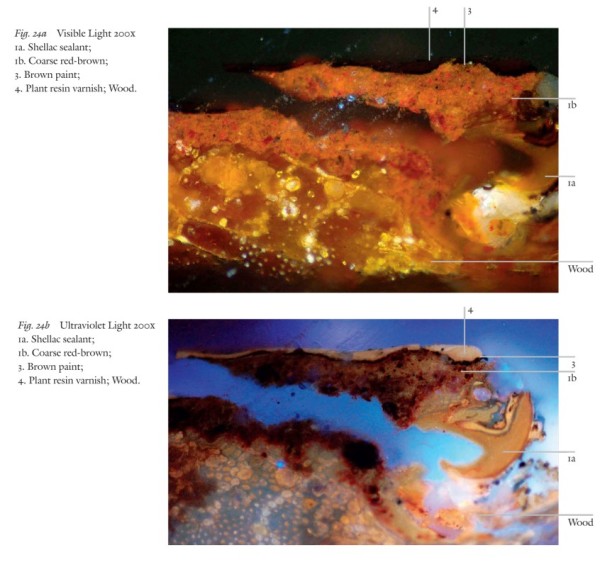

F24-6. Desk, top edge of writing surface support at large losses.

F24-7. Desk, rectangular block below writing surface, front edge at top where there are considerable losses.

F24-8. Desk, writing surface edge, near PR side.

F24-9. Desk, base of PL writing surface support.

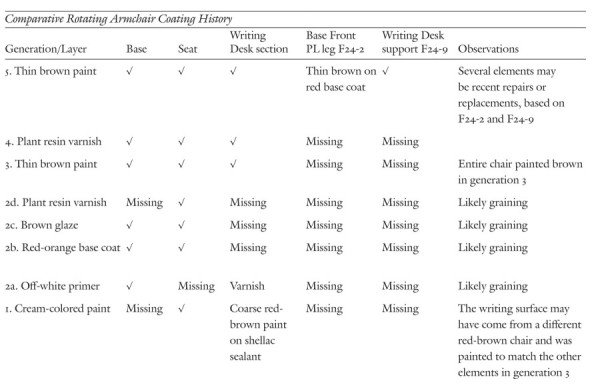

Comparative paint history table. This shows how the comparative paint histories on different elements can be aligned.

A COMPARATIVE CROSS-SECTION microscopy analysis investigation was undertaken to identify the paints and varnishes on different parts of Thomas Jefferson’s rotating Windsor armchair owned by the American Philosophical Society (fig. 1). It was hoped that tiny paint samples from protected locations would provide important insights into the timing for the creation of the rotating function and the writing desk addition. Since the dates for the alterations are unknown, it was important to establish the original appearance of the primary seating component and how that relates to the physical changes in the chair.

The process began with a careful examination of the surfaces with a 10x monocular loupe (Dermlite DL100) to look for areas where paints and finishes seemed to be undisturbed. This was important because much of the chair has undergone substantial refinishing. Fourteen tiny samples were taken with a scalpel and placed into labeled baggies, and the sample locations were marked with small tags that were photographed for reference. The methods employed for this type of cross-section microscopy paint analysis, using reflected visible and ultraviolet light illumination, were established in the 1980s and have been refined as improved microscopes and digital imaging capabilities have become more readily available.[1]

When the chair was examined at low magnification it was possible to see dark red, brown, and whitish paints in some areas below the current glossy dark brown finish. The more exposed areas of the chair are badly worn, and there is evidence of refinishing on the writing desk edges and seating surface. Samples were taken from protected edges and at the joins of the stretchers and legs, where the surfaces appeared to be more intact and early finishes might have survived. The evidence derived from the cross-section samples from each portion of the chair is discussed and illustrated here, beginning with the samples from the seating section, which has the longest paint history.

The armchair seat appears stylistically to be the oldest portion of the chair, so it was not surprising to find that the paint samples from this component retain the longest and most complete paint history. Four of the five samples retain compelling evidence of the changes in colors and decorative finishes over time. Sample 10 was compromised by earlier stripping efforts and thus is not as helpful in establishing the coating stratigraphy for the seat, so the findings for samples 11 through 14 (fig. 2-5) are explained and illustrated below.

Windsor Chair F-24 Chair Seat Sample Locations:

No. 10. Chair seat, PR side, top of spindle, third back from arm support, at large loss (fig. 2).

No. 11. Chair seat, PL side of seat near front, below incised line, spot of bronze powder paint (fig. 3).

No. 12. Chair seat, side of PR arm, just in front of iron strap.

No. 13. Chair seat, underside of crest rail, near scroll, PR side at large loss area (fig. 4).

No. 14. Chair seat, top of seat, adjacent to spindle at rear (fig. 5).

The paint evidence on the seating section is somewhat disrupted from wear and restoration work, but there is still enough to reconstruct its finish history of five generations of coatings. This chair was originally painted with one thick layer of white lead-based, cream-colored, paint, which is most obvious in samples F24-12, F24-13, and F24-14. This original creamcolored paint became eroded and etched before it was repainted with a redorange paint that aligns with the first paint on the wood in the samples from the base. There is a thin brown glaze and a plant resin varnish associated with this red-orange paint, suggesting that this sequence of three coatings represents decorative grain painting. After the varnish had become worn and cracked, it was painted over with a thin brown paint, followed by a plant resin varnish. The most recent brown paint and the varnish are discolored and cracked, and are consistent with aged coatings.

Sample F24-14 represents the most complete and readily decipherable coating cross-section, with clear evidence that the surface of the first creamcolored paint became cracked and discontinuous before it was painted over with the red-orange graining base coat.

F24-11. Chair seat, PL side of seat near front, below incised line, near spot of bronze powder paint (fig. 6). One sample was taken from what appeared to be bronze powder paint on top of the red-orange paint when examined at 10x during sampling. However, no gold or bronze powder paint was found in this cross-section, nor in the uncast samples. It is possible the edge of the chair had later gilded or bronze powder paint striping, but no solid evidence for this decoration was found in the samples. The first paint on top of the wood is the cream-colored, oil-bound paint (1) identified as the first layer in all the samples from the seat. There is only a fragment of the red-orange base coat above it (2a). The paints in this area are quite embrittled, and they shattered apart during sampling (fig. 6).

F24-12. Chair seat, side of PR arm, just in front of iron strap (fig. 7). The coating history on the side of the PR arm has four generations of coatings, beginning with the original cream-colored paint (1). There are only remnants of the red-orange base coat (2a) and varnish (2c) here, followed by a thin brown paint (3) and plant resin varnish (4).[2]

F24-13. Chair seat, underside of crest rail, near scroll, PR side at large loss area. The paint history on the crest rail scroll (F24-13) and the top of the seat (F2414) are the same, with evidence that the original cream-colored paint (1) had become quite uneven and eroded—possibly from wear or sanding—before it was covered over with the red-orange base coat (2a). The brown glaze (2b) for the graining is discontinuous, but the aged, cracked plant resin varnish (2c) is still relatively intact. The brown paint in generation 3 flowed into cracks in the varnish beneath when it was applied. The top coating is a thick layer of plant resin varnish (4), with considerable grime on its surface (fig. 8).

F24-14. Chair seat, top of seat, adjacent to spindle at rear. The original creamcolored paint (1) in this cross-section is deeply fissured, with grime on its surface. It is followed by the red-orange base coat (2a), uneven brown glaze (2b), and fractured plant resin varnish (2c). The thin brown paint (3) extends over this damaged varnish layer. There is an accumulation of synthetic glue (identified by its bluish autofluorescence) that extends across the brown paint in generation 3. The most recent thin brown paint (5) is on top of the glue, which is most obvious in the reflected ultraviolet light image (fig. 9).

Binding media analysis with biological fluorochrome stains confirmed that all the paints contain oil components (with the fluorochrome DCF).[3]

When the cast cross-sections are repolished, additional details about the individual layers can sometimes emerge. So when cross-section F24-14 was repolished, it was possible to see the boundary and the cracks between the cream-colored paint (1) and the red-orange base coat (2a) more clearly, confirming that they are separate paint generations.

This evidence shows that the seat section was originally painted with an oil-bound, cream-colored paint. Then it was grain-painted in the second generation, which seems to be when it was joined to the rotating base. Polarized light microscopy (PLM) analysis was conducted to identify the pigments in the earlier paints to make sure that they are consistent with the age of the chair. All the pigments in the original cream-colored paint and the second-generation red-orange base coat for the graining were readily available in the eighteenth century and relatively inexpensive.

Pigment analysis shows that the cream-colored paint comprises primarily white lead and calcium carbonate, with scattered red ochre and yellow ochre pigments. The red-orange base coat for the graining is primarily composed of red ochre, hematite, and calcium carbonate.[4]

Five samples were taken from protected areas of the base to establish the complete coating chronology for the elements that all likely date to the conversion of a traditional Windsor armchair to a rotating form. The sample locations were tagged for reference, and although the current finish is clean, smooth, and glossy, the samples were taken from areas that would have been more difficult to completely refinish.

Windsor Chair F24 Base Sample Locations:

No. 1. Base, top edge of base for turned seat mechanism.

No. 2. Base, top edge, front Proper Left (PL) leg.

No. 3. Base, at join with central stretcher with PL side stretcher.

No. 4. Base, PL side, rear edge of stretcher at join with rear PL leg.

No. 5. Base, PL side leg, in bottom bamboo turning near join with stretcher.

Most of the paints and varnishes found in the cross-sections from the base can be aligned to establish a complete coating chronology for this component. The cross-sections show that the coatings in the most complete crosssections can be aligned with generations 2 through 5 on the armchair seating section. The coating histories from the base are compared with those from the seat and writing desk in the conclusion of this report.

F24-1. Base, top edge of base for turned seat mechanism. The coating history in sample F24-1 from the base below the seat is easiest to interpret in the reflected ultraviolet light cross-section image, since the substrate is darkened and disrupted (fig. 11). There are remnants of a red-orange paint trapped in the wood. This matches the red-orange base coat (2b) for graining found in samples F24-3 (fig. 13) and F24-5 (fig. 14). It is followed by a thin brown paint identified as generation 3 in the comparative coating chronology. Above that is a thick plant resin varnish (4) on top of the brown paint that was identified based on its characteristic whitish autofluorescence. The dark brown paint on the top is the current coating on the armchair, and it can be aligned with generation 5 on other parts of the chair. The sampled area at the top edge of the turned seat mechanism was likely worn from use, but the coatings on the base were also compromised by the partial stripping and refinishing that took place during later restorations and repairs.

F24-2. Base, top edge, front Proper Left (PL) leg (fig. 16). Cross-section F24-2, from the front Proper Left (PL) leg, has a paint history that suggests a more recent replacement or repair. The wood substrate in this sample is bright and unoxidized, and the two paints on top of the wood may comprise the coatings applied after the most recent restoration. There is a finely ground deep red paint on the wood, followed by the most recent dark brown paint. There is no boundary or evidence of aging on the surface of the deep red paint, so it is likely that these two coatings are the same generation and were applied to match the surrounding surfaces. They have been labeled as layers 5a and 5b to align with most recent coatings in the other cross-sections from the armchair section. This evidence suggests that either the leg is a replacement, or there is a recent patch or repair at the top of the leg where the sample was taken.

F24-3. Base, at join with central stretcher with PL side stretcher. The coating history on the stretcher was initially puzzling since it appeared to align with the paints on the seating section. But there are important, subtle differences between the paints in F24-3 and F24-5 from the base and samples F24-10 through F24-14 from the seat. The original paint on the seating section is a thickly applied, oil-bound, cream-colored paint, while the first layer on the base in F24-3 is a thinly applied off-white, oil-bound paint (fig. 17). These early cream-colored and off-white paints appear similar in cross-section but are not the same. The combined evidence shows that the off-white paint on the wood in F24-3 and F24-5 is a primer, not a finish coat. There is no boundary or edge between this off-white paint and the red-orange paint directly above it, while the earliest cream-colored paint on the seating section is a finish coat that degraded before it was painted over.

There are some clues to suggest that the off-white primer (2a) and redorange paint (2b) are part of the grain-painting sequence since there are remnants of a red-brown glaze (2c) on top of the red-orange base coat. This potential graining sequence was also found as the second generation in all the samples from the seat. The third generation is a thin brown paint (3), followed by a degraded plant resin varnish (4), and then by the most recent thin brown paint (5) (fig. 18).

The binding media components of the paints in F24-3 were analyzed with biological fluorochrome stains to mark the presence of carbohydrates (with TTC), proteins (with Alexafluor 488), and oils (with DCF). This analysis showed there are no carbohydrates, like plant gums or sugars, present in any of the coatings. All the paints reacted positively for the presence of oils, and no reactions were observed for the presence of proteins.

F24-4. Base, PL side, rear edge of stretcher at join with rear PL leg. Only limited paint and varnish evidence remains in sample F24-4. Remnants of the off-white primer (2a) remain on the wood, followed by an uneven layer of thin brown paint (3). In reflected UV light it is possible to see an uneven film of plant resin varnish (4). There is a remnant of modern glue on top of the varnish on the right side of the cross-section (fig. 19).

F24-5. Base, PL side leg, in bottom bamboo turning near join with stretcher. The paint history in F24-5 is similar to the layers identified in sample F24-3 from the stretcher. The earliest coatings (at the bottom) consist of the offwhite primer (2a) and red-orange base coat (2b), but there is no obvious brown glaze layer associated with the red-orange base coat. Generation 3 is a thin dark brown paint, followed by a deeply cracked plant resin varnish (4). The most recent brown paint (5) is the current finish on the chair (fig. 20).

It was important to establish the timing for the writing desk component in the overall paint chronology for the armchair. When elements of the writing desk section were examined at 10x, it appeared there were far fewer paint and finish layers, and the wood substrate in sample F24-9 appeared to be bright and unoxidized. It was difficult to find good locations for sampling from the writing desk surface not already compromised by refinishing or abrasion, but sample F24-6 fortunately retained solid early paint evidence.

Windsor Chair F-24 Desk Sample Locations:

No. 6. Desk, top edge of writing surface support at large losses.

No. 7. Desk, rectangular block below writing surface, front edge at top where there are considerable losses.

No. 8. Desk, writing surface edge, near PR side.

No. 9. Desk, base of PL writing surface support.

F24-6. Desk, top edge of writing surface support at large losses. The early paint history on the writing desk section is quite different from that of the rotating base and the armchair section. There is shellac (1a) trapped in a pore in the wood (identified based on its characteristic orange autofluorescence in reflected UV light) on the right side of the cross-section. This shellac was not found in the other cross-sections, so perhaps it was a sealant that was unevenly applied prior to painting. There is a distinctive, coarsely ground, oil-bound, red-brown paint (1b) on top of the wood. This paint was found only in the samples from the writing desk section, so even though it is labeled as generation 1 on the base, it may not be concurrent with the generation 1 cream color on the seating section (fig. 24).

The thin brown paint above the coarse red-brown was identified as generation 3 in samples from the base and seating section, and it is followed by the same plant resin varnish identified as generation 4 in the cross-sections from the other base and seat elements.

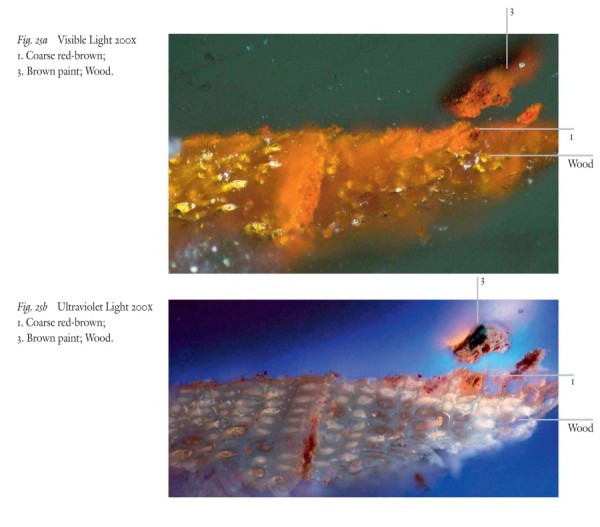

F24-7. Desk, rectangular block below writing surface, front edge at top where there are considerable losses. The layers are more disturbed in this cross-section from the block support in the writing surface, but enough remains of the first coarse, oil-bound, red-brown paint to show that this rectangular block was also originally painted red-brown (1). The coarse red-brown is followed by the thin brown paint identified as generation 3 in samples from other elements of the chair (fig. 25).

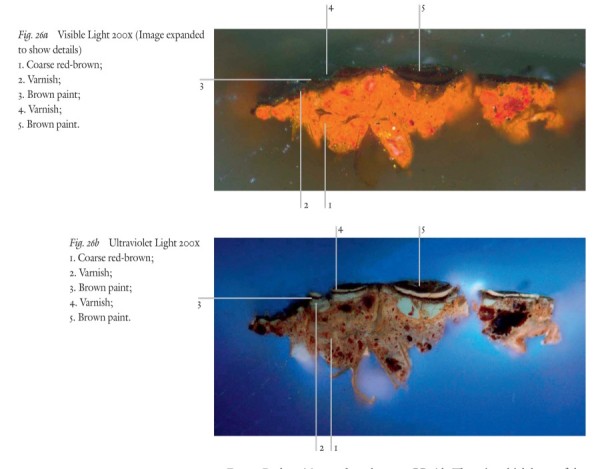

F-24-8. Desk, writing surface edge, near PR side. There is a thick layer of the first coarse red-brown paint (1) in this cross-section from the edge of the writing surface. In reflected UV light there is a cracked, degraded layer of plant resin varnish (2) that was applied after the red-brown paint surface had become deeply cracked and uneven. It is followed by a thinly applied brown paint (3), and then a plant resin varnish (4). The most recent brown paint is generation 5 see figure 26.

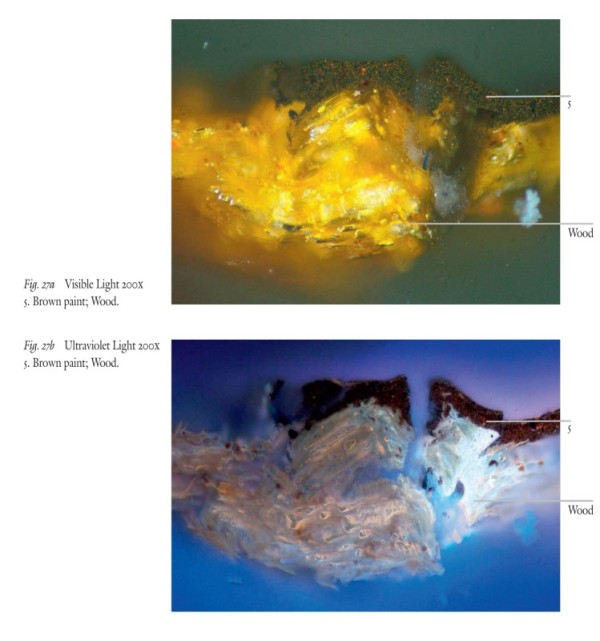

F24-9. Desk, base of PL writing surface support. It is likely that this turned support for the writing surface is a later addition or part of an extensive twentieth-century repair since there is modern glue trapped in the cracked wood surface and the only coating is a thick layer of the most recent brown paint (5) see figure 27.

Conclusion

This comparative paint investigation posed challenges for interpretation because initially it appeared that the paint history on several elements of the base (stretcher and leg) matched that of the armchair seating section. Stylistically these elements are quite different and are likely to be from different periods of construction. There is evidence of grain-painting as the original finish on the base (see samples F24-3 and F24-5 from the base), while the same graining is the second generation in the samples from the armchair seating section. No evidence of this graining was found on the writing desk elements; rather the most complete cross-section (see samples F24-6 and F24-8) suggest that it was originally painted with a coarse redbrown paint not found elsewhere on the armchair.

The primary difference between the base and the seating section is that the seating section was originally painted with a thickly applied, cream-colored paint that collected grime and cracked before the red-orange graining base coat was applied (see F24-13 and F24-14). By comparison, it appears that many elements of the rotating base were first painted with an off-white primer, and then the red-orange graining base coat was applied (see F24-3 and F24-5). This indicates that when the base and armchair section were joined they were grain-painted to match. The presence of a red-orange base coat color for the graining suggests that it could have been intended to mimic mahogany, or possibly rosewood. The writing desk surface was not grain-painted, but the coarse hand-ground paint is consistent with late eighteenthor early nineteenth-century practices.

The comparative paint histories thus suggest that the original armchair was cream-colored, and then, when the rotating base was joined to the seating section, the entire chair was grain-painted. The writing desk section was originally red-brown, so perhaps it was taken from a different chair, and when it was joined to the rotating armchair, the entire object was repainted brown in generation 3. The comparative paint history does not precisely date the writing desk section, but it does indicate that it is one generation later in the paint history than the creation of the rotating chair. The preceding table (fig. 28) shows how the comparative paint histories on different elements can be aligned (fig. 28).

At the lab the samples were sorted and examined under a binocular microscope at 40x, and the best samples were selected and placed in polyester resin cubes in mini ice cube trays. After the polyester resin had cured, the cubes were ground and polished for cross-section microscopy analysis and photography. The cast samples were analyzed with a Nikon Eclipse 80i epi-fluorescence microscope equipped with an EXFO X-Cite 120 Fluorescence Illumination System fiberoptic halogen light source and a polarizing light base using SPOT Advanced software (v. 5.1) for digital image capture and Adobe Photoshop CS for digital image management. The samples were photographed in reflected visible and ultraviolet light using a UV-2A filter with 330–380 nm excitation, 400 nm dichroic mirror and a 420 nm barrier filter, and a B-2A filter with 450–490 excitation and a 520 nm barrier filter. Photographs were taken at 100x, 200x, and 400x magnifications.

Certain fluorescence colors can indicate the presence of specific types of materials. For example, shellac fluoresces orange (or yellow-orange) when exposed to ultraviolet light, while plant resin varnishes (typically amber, copal, sandarac, and mastic) fluoresce bright white. Wax does not usually fluoresce; in fact, in the ultraviolet it tends to appear almost the same color as the polyester casting resin. In visible light, wax appears as a somewhat translucent white layer. Paints and glaze layers that contain resins as part of the binding medium will also fluoresce under ultraviolet light at high magnifications.

Three fluorescent biological fluorochrome stains were used for examination of the samples: Alexafluor 488 0.02% in water, pH 9, 0.05M borate and 5% DMF was used to identify the presence of proteins, and its positive reaction color is yellowish-green under the B-2A filter. Triphenyl tetrazolium chloride (TTC) 4.0% in ethanol was used to identify the presence of carbohydrates (starches, gums, sugars), and its positive reaction color is dark red or brown under the UV filter. 2, 7 Dichlorofluorescein (DCF) 0.2% in ethanol was used to identify the presence of saturated and unsaturated lipids (oils); the positive reaction for saturated lipids is pink and for unsaturated lipids, yellow, under the UV filter.

Pigments from individual paint layers were dispersed and crushed onto microscope slides with a scalpel. These dispersed samples were permanently mounted under cover slips with Cargille MeltMount with a refractive index of 1.66. The samples were examined under plane-polarized transmitted light and crossed polars (darkfield) at 400x and 1000x, and the unknown pigments were compared to standard pigment reference samples.