Map of South East England showing Beccles, Colchester, Ipswich, and London, the known locations of Francis Trumble prior to 1740.

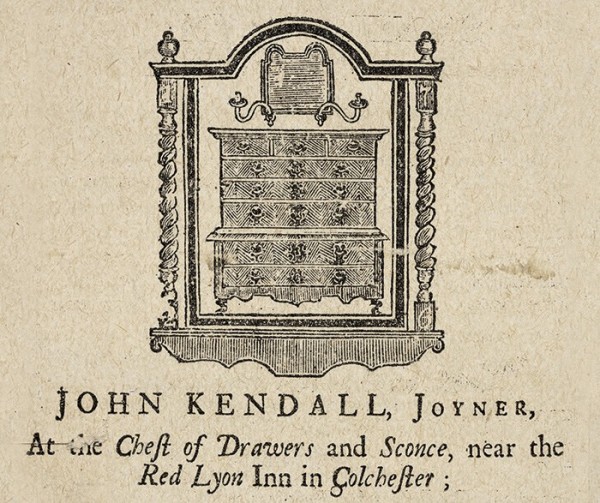

Trade card of John Kendall, cabinetmaker, 1726. Illustrated in Essex County Standard, August 1, 1931. (© Trustees of the British Museum.)

Samuel Wale (1721-1786), John Sheppard Escaping from Newgate, undated. Pen, gray ink, and gray wash on paper. 6" x 4". (© Trustees of the British Museum.)

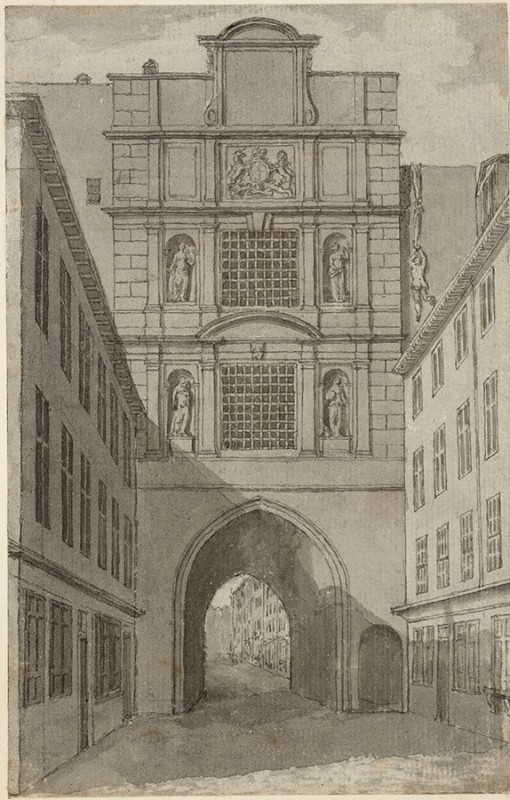

Frederick Nash, The Press Yard, Newgate Prison, ca. 1840. Watercolor on paper. (© London Metropolitan Archives / Bridgeman Images.)

High-back Windsor armchair, attributed to Francis Trumble, Philadelphia, 1755–1762. Yellow poplar (seat) with maple, oak, and hickory (microanalysis). H. 44 7/8", W. (arms) 26 3/4", D. (seat) 16 3/4". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

Low-back Windsor armchair, possibly by Francis Trumble, Philadelphia, 1760–1770. Yellow poplar, ash, white oak, soft maple, and hickory (replaced right stretcher, beech). H. 28 3/8", W. 27", D. 21 3/4". (Courtesy, Bayou Bend Collection, gift of Miss Ima Hogg.)

Sack-back Windsor armchair, branded by Francis Trumble, 1770–1785. Tulip, soft maple, walnut, hickory, and oak (microanalysis). H. 37 13/16", W. 21 1/16“, D. 15 15/16". (Courtesy, Independence National Historical Park.)

Fan-back Windsor side chair, branded by Francis Trumble, Philadelphia, ca. 1778–1785. Yellow poplar, maple, black walnut, oak, and hickory (microanalysis). H. 35 3/4", W. 23 1/2", D. 19 1/4". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

Bow-back Windsor side chair, branded by Francis Trumble, 1788–1795. Tulip, soft maple, white oak, and hickory (microanalysis). H. 35 9/16", W. 16 1/2", D. 16 9/16". (Courtesy, Independence National Historical Park.)

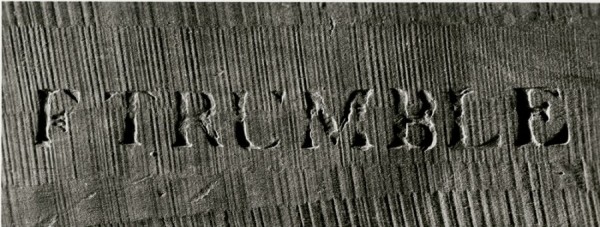

Detail of brand on underside of seat of chair in fig. 9. (Courtesy, Independence National Historical Park.)

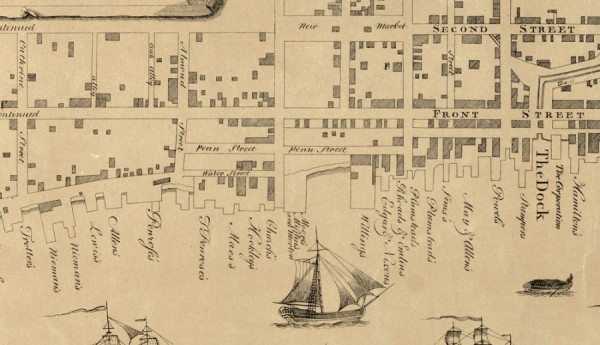

Detail of Nicholas Scull’s Plan of the Improved Part of the City of Philadelphia, 1762; reprint, 1858. The circles indicate the locations of Francis Trumble’s shops and residences. (Courtesy, Historical Society of Pennsylvania.)

James Thackara, A View of the New Market, Philadelphia, 1787. Engraving on white wove paper, 3 7/16" x 6 5/8". (Courtesy, Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia, acc. no. 1876.9.481s.)

Buck Tavern, Moyamensing, Pennsylvania. Photograph, 1907. (Courtesy, Athenaeum of Philadelphia.)

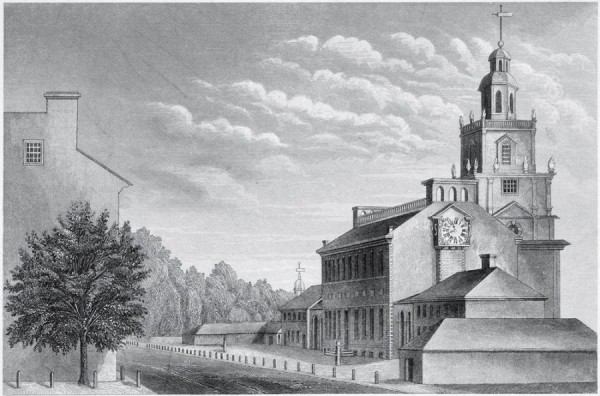

Illman Brothers after Charles Willson Peale, The State House in Philadelphia, 1778, 1876. Engraving on paper. 7 1/2" x 9". (Courtesy, Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa, Oklahoma.)

Edward Savage after Robert Edge Pine, Congress Voting Independence, 1906. Stipple and line engraving from unfinished plate. 18 7/8" x 25 11/16". (Courtesy, Reynolda House Museum of American Art, affiliated with Wake Forest University, gift of Barbara B. Millhouse.)

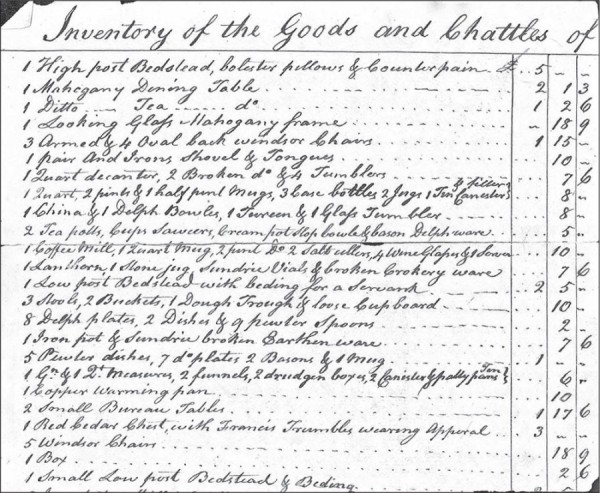

“Inventory of the Goods and Chattles of the Estate of Francis Trumble deceased,” p. 1 (fragment). Pennsylvania, U.S., Wills and Probate Records, 1683–1993, Ancestry.com.

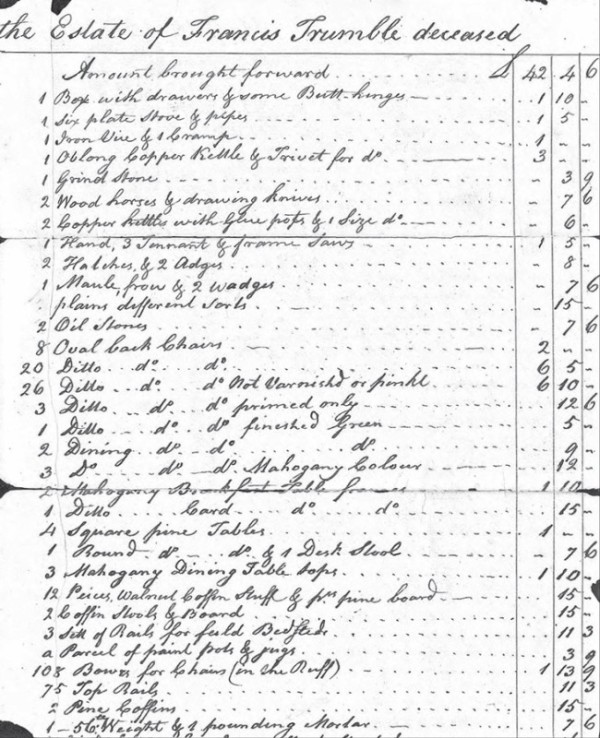

“Inventory of the Goods and Chattles of the Estate of Francis Trumble deceased,” p. 2 (fragment). Pennsylvania, U.S., Wills and Probate Records, 1683–1993, Ancestry.com.

Editor’s note: This article expands upon the study by Nancy Goyne [Evans] written sixty years ago, while Evans was a graduate student, and published in the first issue of Winterthur Portfolio, edited by Milo M. Naeve (Nancy A. Goyne, “Francis Trumble of Philadelphia: Windsor Chair and Cabinetmaker,” Winterthur Portfolio 1 (1964): 221–241). Since much of the newly found material overlaps with Evans’s article, the two have been integrated in order to provide a clear narrative. Substantial excerpts from the 1964 article as well as material from Evans’s subsequent writings are reproduced here in brown text to distinguish her work from the recent findings of James Gergat.

CONVICTED ROBBER, DEATH ROW inmate, wayward Quaker, high-risk entrepreneur, and furniture maker. Francis Trumble was all these things, yet he is primarily known today as a maker of Windsor chairs. Trumble’s years in Philadelphia, from 1740 to his death in 1798, were the subject of Nancy Goyne Evans’s 1964 article in the first issue of Winterthur Portfolio. Evans’s article documents Trumble’s business operations as gleaned from a variety of sources, including shipping records, legal documents, newspaper advertisements, miscellaneous business accounts, and extant Windsor chairs bearing his brand. New data from previously unexplored sources expand upon Evans’s work and, in particular, uncover his origins, professional training, and troubled life in England. While Trumble may not represent the immigrant experience as a whole, the trajectory of his life reveals the extent to which opportunity and reversal of fortune were possible in eighteenth-century America.

Francis Trumble was born in England on November 30, 1715, the eldest son of Quakers living in Beccles, a market town in Suffolk about a hundred miles northeast of London. His childhood household comprised his parents, Francis Sr. (ca. 1686–1739) and Esther Trumble, of Suffolk, and an older sister, Esther (b. 1713). As indicated by court testimonies detailed below, the Trumbles then lived in Ipswich, and at the age of twelve or fifteen, the younger Francis began his apprenticeship in Colchester, Essex County (fig. 1). His master was John Kendall, a cabinetmaker and joiner in Colchester. Kendall’s 1726 trade card (fig. 2) identifies Kendall’s occupation as a joiner and lists a large variety of forms made in his shop, along with other wares retailed by Kendall:

JOHN KENDALL. Joyner

At the Chest of Drawers and Sconce, near the

Red Lyon Inn in Colchester;

MAKES and Sells all Sorts of Joiners and Cabinet

Makers Goods: As Chests of Drawers, Cabinets,

Writing-Desks, Book-Cases, Scrutores, Hanging Presses, Nap-

kin-Presses: All Sorts of Chamber-Tables, Oval-Tables, and

Compass-Tables, &c. He also selleth all Sorts of Glasses;

as Pier-Glasses, Chimney-Glasses, Sconces, Brass and Glass

Arms; All Sorts of Japan Goods, as Corner-Cupboards, Tea-

Tables, Tea-Boards, Salvers, Landskips, and Dutch Tables:

Choice of Canes, Maps, and Prints: Also all Sorts of Wo-

mens and Childrens Shoes, Cloggs, Pattens, &c. By Whole-

sale and Retail at very reasonable Rates.

It can reasonably be assumed that as an apprentice, Trumble would have been trained in the production of many, if not all, of the furniture forms listed above. Trumble probably worked alongside other apprentices and journeymen in the same shop and may have known and worked with other local furniture makers, such as Thomas Kendall (fl. 1697–1724), possibly John’s older brother, and Thomas’s previous apprentices William Mumford and Humphrey Mayhew. On May 15, 1738, Trumble married Sarah Catchpool (d. 1762) in Beccles; their wedding was formally blessed by the Colchester Monthly Meeting. His marriage and age (twenty-two) suggest that he had completed the standard seven-year apprenticeship term and was able to pursue a livelihood. The couple appears to have moved soon after to London, where on March 30, 1739, their daughter, Sarah (1739–1806), was born in Jerusalem Court, Clerkenwell.[1]

Just three and a half months later, Trumble was a convicted criminal. The commentary and testimonies from his court trial not only detail his crime but also provide rare insight into a life already replete with psychological stress. As recorded in the notebook of Justice Henry Norris, on June 18, 1739,

Francis Trumble brought by Henry Harrill one of the Headboroughs of the parish of St John at Hackney and charged by Thomas Browne on Oath on Violent Suspicion of having about Six of the clock in the Evening of this day Assaulted him in a certain field or open place near the Kings high Way near Brook house in the said parish and Feloniously took from him a Silver Watch his property.

Trumble was remanded to Newgate Prison (fig. 3), where he awaited his trial, held a month later on July 18 at the Old Bailey. At the trial, several witnesses for the prosecution confirmed the statement of the victim, clothworker Thomas Browne, who described being held up by a masked man who absconded with his watch and was apprehended after a lengthy chase over fields. According to constable Harrill, Trumble upon capture was “very solitary, and a Sort of Wildness appeared in his Eyes; and when any Question was ask’d him, he turn’d about, and look’d wistfully.”[2]

Witnesses for the defence did not refute the charge and instead portrayed a young man with a difficult childhood who was until recently an upstanding member of society. Thomas Steed, who had lived next door to the Trumble family in Ipswich, recounted details of what must have been a turbulent upbringing. Francis’s mother “was many Times beside herself; she made many Attempts to destroy her Life, and at last she hang’d herself.” His father was also “several Times out of Order” and possibly delusional, for he once came to Steed’s house and refused to eat, saying that “if he did he should be choak’d, and should die at the next high Water.” Nevertheless, Steed noted that the young Francis behaved well and left Ipswich at the age of twelve to begin his apprenticeship in Colchester. Another witness, Eleanor Young, noted that she had known Trumble for seven years and, aside from the last couple of months, she “never heard any thing amiss of him before, and observed that he work’d industriously at his Business of a Cabinet-maker.” However, about two months prior to robbing Thomas Browne, Francis Trumble had heard that his father, a shipmaster, had drowned. This event triggered what appears to have been a psychotic episode. Young recounted that Trumble had been “disorder’d in [his] Senses ever since the Death of his Father . . . That he appear’d as a Man disturb’d, and to have had his Mind full of Trouble . . . he often appear’d melancholy, and would immediately be in a flurry, and look wild.” She also testified that three days before Trumble had committed his crime, he had shut himself in a house near Hicks Hall, the site of the Middlesex Sessions House and less than a quarter of a mile from Jerusalem Court in Clerkenwell, where his daughter had been born three and a half months earlier. John Sawyer, who had known Trumble for twelve years, also noted that about two to three days before the crime, Trumble “appear’d very melancholy, and to be much disorder’d, which he imputed to the Uneasiness created in his Mind by the Death of his Father . . . [and] appear’d to have strange Notions of having a great deal of Business upon his Hands, —so much— . . . that he started from one Thing to another, and appear’d disorder’d in his Understanding.” However, Sawyer also stated that he “could not say he [Trumble] knew no Difference between Good and Evil.” Similar accounts from Francis Young and Wilford Head corroborated these statements and affirmed or did not refute Trumble’s ability to distinguish good from evil. Additional witnesses testified to Trumble’s state of mind while in confinement. According to these witnesses, Trumble threatened to cut his own throat, tried to hang himself, and a candle was kept burning all night so that others could make sure he did not commit suicide.[3]

Because the defence failed to establish lunacy or the inability to differentiate between good and evil, Trumble was found guilty of “assaulting Thomas Brown on the King’s Highway . . . putting him in Fear, &c. and taking from him a Silver Watch, val. 30s., an Iron Chain, val. 2d. and a Brass Seal, val. 1d.” and, along with three other men and one woman during the same session, sentenced to death. After being instructed on the necessity of punishing transgressions of the right to individual property in a civilized society, all prisoners attended the prison chapel,

excepting Francis Trumble, who was born and bred a Quaker, and he being very sick, weak and disordered in his Senses, was not able to come to Chapple, nor scarcely to speak to any. His Disorder increased with his Confinement, and when he was let out in the Press-yard (fig. 4) for a little Air, he look’d wild, and star’d, but spoke nothing. He continues in so weak and so unhappy a Frame of Mind, that he was not able to give any Account of himself, only in general Terms he promiseth to be more circumspect for the future, if his Life should be spared, and said he truly repented of the Crime he had committed.

On July 27, like almost half of those sentenced to death, Trumble was granted a Royal pardon along with Sarah Kingman, the only woman given a death sentence during the same session, whereas the other three men were slated for execution. While the mildness of a crime increased the likelihood of a reprieve, Sarah’s gender and possibly Francis’s mental instability may have also played a role. Trumble’s and Kingman’s pardons were qualified by being ordered “for 14 Years Transportation,” indicating that they were required to leave the country. On September 13 Trumble was released from Newgate, and five months later his name is recorded in Philadelphia.[4]

Philadelphia proved to be an ideal setting for Francis Trumble to reverse his fortunes. As a furniture craftsman actively engaged in his trade for over half a century, Trumble was perhaps unique in Philadelphia in his day. In the volume of business handled by his shop, he was more typical. Records pertaining to eighteenth-century furniture craftsmen are not plentiful, but in a city with an estimated population in 1740 of 13,000, which had increased to 40,000 by 1776, the various furniture shops must have enjoyed a brisk trade in order to meet the needs and demands of society. It is not unlikely, then, that Trumble’s business, while extensive, was not extraordinary, and were additional craftsmen’s records to come to light, they might reveal that a similar scope and volume of trade was enjoyed by other Philadelphia furniture shops in this era.[5]

Trumble produced fine furniture from the early 1740s and Windsor chairs from the mid-1750s until 1798. These years of his craft activity embraced three distinct style periods in American furniture making. Newspaper advertisements and bills from Trumble’s shop reveal a considerable production of fine furniture in the styles today designated as Queen Anne and Chippendale. While later evidence is scant, the indications are that sophisticated furniture was still being produced by Trumble during the Federal period. Of the fabrication of utilitarian furniture, there is ample evidence that the Windsor production of Trumble’s shop reached expansive proportions during the last four decades of the century. Quantities of these relatively inexpensive chairs were produced for the local market and the export trade.

In spite of his recent troubles, Trumble appears to have established his business in Philadelphia with relative ease and speed. The earliest of his known transactions are with Quakers and woodworkers, suggesting that both religious and occupational ties played an important role in his acclimation to the local community. Early in his career, Trumble had business dealings with the Quaker chair maker Solomon Fussell (1704–1762). Furniture craftsmen frequently exchanged or purchased goods and services from one another, seeking skills that they lacked or that were economically expedient to purchase. Fussell’s account book shows that on February 19, 1740, Trumble purchased “one Couch” costing £1.04.00, which was paid for in cash thirteen months later. Trumble’s “Couch” probably was a form of daybed with turned members and a rush bottom. This, however, was a strange purchase, since Trumble himself was making a variety of furniture. The indication seems to be that his shop was not yet equipped with a lathe. Turning was a highly specialized skill. Cabinetmakers did not always do their own turning. Rather, they relied on the services of a master in that craft or hired a journeyman turner.[6]

Trumble’s shop, however, was relatively well established by May 1741, when Trumble advertised for a runaway servant, George Keiser, “by Trade a Joyner.” Trumble noted that Keiser had taken with him several articles of clothing and “several small Joyners Tools” and offered a reward of forty shillings. The advertisement documents that within a year and half of his arrival, Trumble had formed a business and was successful enough to hire a servant (and pay a forty shilling or two-pound reward). Around the same time, he entered into an annual lease of a house from Nathaniel Allen (1686–1757), a prominent Quaker and cooper. The first of each April from 1741 to 1744, Allen entered nine pounds against Trumble’s account for “a years Rent for ye hous he lives in.” Except for two cash payments, the craftsman paid his rent in furniture and services. Trumble’s rented house probably included his shop as well. Maintaining both a business and a dwelling in the same or adjacent building was a common practice among craftsmen in eighteenthcentury Philadelphia.[7]

In addition to cash, Trumble paid his rent with bartered goods and services. These goods and his other early sales of furniture during the early 1740s demonstrate that Trumble was making high-style forms and supplied goods for venture cargo. The “furniture payments” that Francis Trumble made early in his career to Nathaniel Allen in exchange for his house rental provide a valuable insight into the nature of this craftsman’s work in the decade prior to the mid-eighteenth century:

1742

2mo20 By a Cofin had for my Wife ye 19dy 7 mo 1740 £02.10.00

By a Walnut Table to Hannah Webb 02.15.00

10mo28 By mending & altring 2 Wallnut tables

10/ hinges & Screws 13/ 01.30.00

1743

3mo17 By a wolnut Desk for Nehemiah 06.00.00

1743 By a Cornish Bedsted 32/ & Curting Rods

18 [and] Stapel[s] 18/8 02.10.08

By mending a Clock Case 00.12.00

1744

5mo20 By a Dobell [double] Chest of Draws 08.00.00

1745

5mo4 By a Desk maid of Wallnut for self 06.15.00

By a Coffin for Black Sarah 00.15.00

By a top for a Stand 00.2.06[8]

An account of the work done for several other merchant families in this period further enlarges the picture. In April 1745 Trumble “Received of Samuel Powel Junior one pound ten shillings infull for a table for Ship Sarah[’s] galley.” The McCall family made two purchases of a domestic nature. Margaret McCall “Pd Francis trumble for a chest of drawers” costing £9 in May 1746, and Samuel McCall Sr. purchased six chairs at £7.10.00 two years later. These were probably walnut chairs since both Windsor and rush bottomed chairs cost less than one pound apiece.[9]

Early in his career Trumble began producing furniture to be exported to other American colonial regions. Sometimes he acted as his own agent; at other times he transacted his business through a representative. Frequently he sold directly to a merchant who then shipped the furniture at his own risk. In 1741 the letterbook of Samuel Powel Jr. shows the purchase of furniture made by Trumble that was shipped to Barbados on board the Speedwell for the “Accot & Risque of Benjamin Hawkins of Bbbds Merchant and to him self goes consigned vizt”:

One Mahogony fluted Chest on Chest with Drawers &

one Dressing Table to ditto £17.00.00

10 Mahogony Compass Seat Chairs 39/ 19.10 .00

10 Black Leather Stuffet Bottoms for ditto 03.00.00

2 Ellbow chairs 47/ 04.14.00

2 bottoms for ditto 7/ 00.14.00

2 Packing Cases 02.02.00

£47.00.00[10]

No matter how efficient and diversified a shop might be, a furniture craftsman had to rely on the services of others. Incidental business expenditures made by Trumble during the late 1740s are revealed in the accounts of several Philadelphia craftsmen and merchants. In 1747 he paid the ironmonger Thomas Paschall £0.01.08 for “mending 2 Saws.” In this period, too, Trumble made a number of interesting dry goods purchases. Solomon Fussell supplied him with a piece of “Girtweb” at ten shillings. The girtweb was essential in the construction of upholstery pieces such as easy chairs, sofas, and side chairs with upholstered seats. From Thomas Penrose (1709–757), Trumble bought twenty-three yards of “check Linnen” in 1749 and two years later, eighty-one yards of Osnaburg (coarse fabric). Considerable quantities of fabric were utilized by craftsmen in upholstering furniture and in making up bed and window hangings. While there is no evidence to indicate that Trumble did any upholstery work in his shop, it was not uncommon for a craftsman to purchase fabrics from a merchant to pass on to the upholsterer.[11]

Further purchases were made in the 1750s from merchants John Smith and John Hatkinson. Hatkinson’s records describe an additional variety of textiles sold to Trumble, including more “chek linen,” some “blew taffety,” and a piece of “Damaske.” In partial payment for the cloth, Trumble supplied Hatkinson with “6 chears” costing £4.04.00. These probably were high-back Windsor armchairs, for there is no evidence that Trumble ever made rush-bottomed chairs. The purchase of another piece of blue damask is recorded in the daybook of the merchant Owen Jones in 1760. Twenty-five ells of the fabric cost Trumble £4.12.00 (an ell was forty-five inches in length by English measure and twenty-seven by Dutch measure).[12]

By 1753 Trumble was living on Society Hill, and his advertisement the following year illustrates the wide range of forms made in his shop:

FRANCIS TRUMBLE, Cabinet and chair-maker, &c . . . makes and sells the following goods in mohogany, walnut, cherry-tree, mapple, &c. viz. Scutores, bureaus, sliding-presses, chests of drawers of various sorts, breakfast tables, dining tables, tea tables, and card tables; also cabin tables and stools. Chairs of all sorts; such as settees, easy chairs, arm chairs, parlour chairs, chamber chairs, close chairs, and couches, carv’d or plain; bedsteads and sacking bottoms, clock cases, corner cupboards, tea chests, tea boards, bottle boards &c. &c. Likewise all sorts of cabinet furniture, at reasonable rates.

N.B. A great assortment of the above goods being ready made, after the newest fashion, any person may be supplied immediately, or on very short notice.

Identifying as both a cabinetmaker and a chair maker, Trumble was unusual among eighteenth-century furniture makers, who for the most part practiced one trade or the other. As indicated by the wares sold by his master, John Kendall, Trumble trained as a cabinetmaker. He may have learned the art of chair making in Colchester or London prior to emigration. He may even have received further training or instruction after his removal to Philadelphia. If so, Trumble was a particularly proficient and ambitious woodworker since he was making refined forms such as compass-seat side chairs within a year and half after his arrival. Because Trumble is known to have had contact with Solomon Fussell in early 1740, he may have worked in the shop of the Quaker chair maker before setting up his own business. His 1754 advertisement also demonstrates that almost fifteen years later, his shop was a substantial enterprise. That he could supply his goods upon short notice and with a variety of forms indicates a good-sized and wellstocked shop with considerable specialized capability and a readiness to meet any request or demand as promised.[13]

The range of furniture advertised above is a good indication of the versatility of this craftsman. Several of the pieces mentioned appear on bills rendered to various customers during the 1750s. The estate of Thomas Davies (1703–1757) was indebted to Trumble for purchases made in 1754, which included:

a bedstead painted 01.11.06

a Wallnut 4 foot dineing table 02.15.00

a Wallnut Closestool Chaire 02.00.00

£06.06.06

The next year a bedstead costing £1.04.00 was made for Thomas Wharton (1730–1782). Apparently the “Cornish of a bed” (which Trumble set up) and the sacking bottom (which he altered) were for use with this bedstead since they were listed on the same bill and under the same date. Around the same time, the letterbook of merchant Thomas Riché (1724–1792) reveals that he apparently was sending furniture “on venture” to St. Croix. The furniture was obtained from Francis Trumble, for Riché mentioned in several pieces of correspondence that “the Cabbinit Whar Is for Accot of Trimbles & Self.” Specific pieces included a desk and bookcase, a marble table and frame, and a small table.[14]

Referring back to Trumble’s advertisement of 1754, it may be noted that although he mentioned “Chairs of all sorts”—and actually listed the types he made—he did not specifically mention Windsors. By this time, however, Windsors were being made and used in Philadelphia, although they had not yet begun to enjoy the widespread popularity they later knew. In 1754 the rush-bottomed chair was still the greater favorite for economy in seating.

Windsors are mentioned as early as 1742 in a Philadelphia inventory, but there is no way of knowing whether or not they were made in Philadelphia. A few years later, however, in 1748, furniture craftsman David Chambers advertised that he was making Windsor chairs at his house and shop “in Plumb Street, on Society Hill.” The earliest actual record of the sale of Windsors in Philadelphia by a local craftsman can be documented for September 14, 1754. At this time merchant John Reynell (1708–1784) was indebted to Jedediah Snowden (1724–1797), a Windsor chair and cabinetmaker, for “2 Double Windsor Chairs with 6 Legs” at a cost of three pounds. Needless to say, these were Windsor settees. Snowden is also known to have delivered “two high back windsor chairs” to Mrs. Mary Coates in May of 1759.[15]

It is apparent that Trumble was one of a small group of craftsmen who early pioneered in the production of Windsor chairs in Philadelphia. Trumble’s earliest documented production of the form was in 1759, when in October of that year the printer-merchant Enoch Story was billed for “6 Winsor Chairs @ 14” costing a total of £4.04.00. Two months later, on December 18, Trumble received “Eight pound Eighteen Shills in full for 12 Winsor @ 14/ chairs [sic] & one Do [ditto] for a child @ 10/” from the merchant Garrett Meade. Meade paid an additional £4.16.00 to Trumble in 1761, presumably for more Windsors. Trumble’s proficiency as a cabinetmaker served him well in his Windsor chair production. As noted by Evans, his early Windsors have “perfectly proportioned” arm supports and “features such as ringed balusters and waferlike disks.”[16]

The specific Windsor styles made by Trumble can be discerned by descriptive terms or implied by prices and reflect the evolution of designs made in midto late eighteenth-century Philadelphia. While the chairs made in 1759 are simply described as “Winsors,” they were most likely high-back or lowback armchairs, the two earliest designs (figs. 5, 6). Priced at fourteen shillings each, they cost less than the “high-backed,” or “high-back,” examples Trumble made in 1761 for eighteen shillings per chair and just slightly more than the thirteen shillings Trumble charged per chair for low-back examples in 1763. Other high-backs made by Trumble in the 1760s range in cost from fourteen to sixteen shillings per chair, suggesting that the price depended on unspecified options such as scrolled or plain handholds. By 1770 Trumble was making sack-back Windsors variously described as “round back,” “round top,” “arch top,” and “sack back” (fig. 7). As noted by Evans, the prices for these forms ranged from thirteen and a half to fifteen shillings per chair, the cost differential probably based on options such as the style of handholds or the use of mahogany arms. The next design to enter production was the fan-back side chair. Chairs of this style (fig. 8) first appear among Trumble’s known commissions in 1780 when he billed Greenberry Dorsey (1752–1807) for “6 Fan back do” at eleven shillings per chair, six and a half shillings less per chair than the sack-back chairs in the same bill (see Appendix). Another side chair design, the bow-back Windsor chair, was introduced into Philadelphia in the mid-1780s (fig. 9). Also called “loop-back” and “oval-back” during the period, its earliest known documentation is in 1787, when Trumble’s former apprentice, John Letchworth (1759–1843), made “8 ovel-back Chairs” for Robert Blackwell. Trumble probably made the design around the same time, but such chairs first appear in Trumble’s known records only in his estate inventory: four oval-back chairs in his house and fifty-eight in his workshop. Windsor chairs were finished in various ways. Early examples might be “pinkt” with a wash on the seat bottom, possibly as a protection against vermin. Most early production was “finished green,” joined later in the century by yellow, white, and mahogany color paint. Black and shades of brown were other choices.[17]

The 1759 bills to Story and Meade comprise the total of Trumble’s documented sales of Windsors in the 1750s and, based upon Trumble’s known furniture production, were a small percentage of his overall output for the decade. In the 1760s Trumble greatly increased his production of Windsor chairs, and thereafter the surviving records suggest that Windsors represented the vast majority of his output in terms of quantity and value. With component parts conducive to mass-production, Windsor chairs could be sold in bulk and were profitable products for the shipping trade.

Philadelphia was advantageously located for the development of waterborne commerce. Flour milled from grain produced in the rich hinterlands became the leading export and was responsible for the city’s rise to pre-eminence among American seaports by the early 1760s. Philadelphians enjoyed not only a profitable overseas trade but an ever-expanding coastal one. Furniture from local shops was sold in nearly every colonial American port in which Philadelphia merchants transacted business—whether in New England, the South, or the West Indies.

Beginning in the early 1760s, a series of documents reveal something of the nature and scope of Trumble’s Windsor production for the Chesapeake Bay trade. His first known transactions were with Zebulon Rudolph (Rudulph) (1735–1772), a Philadelphia merchant. Rudolph evidently was the agent for both Trumble and merchants at Head of Elk (Elkton, Maryland); his accounts charge Trumble with freight costs and credit him with the sale of chairs received by Tobias Rudolph (1721–1787), Zebulon’s father and a merchant at Elk. Freight charges listed by Zebulon Rudolph hint at the means of transporting the chairs from Philadelphia:

To Cash pd in Phila -----------

To Cost p[er] 27 Chairs to Elk from Xteen

[Christiana Bridge] £0.13.06

Consignments bound for the Chesapeake Bay area were placed on board river vessels at Philadelphia and conveyed down the Delaware River to Wilmington on the Christiana Creek. A stop might be made en route at Chester. After leaving Wilmington, a vessel would continue on up the Christiana, passing Newport, until it reached its destination at Christiana Bridge (Christiana, Delaware). From there freight was hauled overland by wagons to Head of Elk. Between 1764 and 1766 it seems that Trumble shipped at least several dozen chairs in this manner to the Elk River region.

Another gentleman with extensive connections both at Head of Elk and throughout the upper Chesapeake Bay area was Levi Hollingsworth (1739– 1824), a flour merchant. A partner with Zebulon Rudolph from circa 1770 to 1772, Hollingsworth was in business in Philadelphia during the greater part of the last half of the eighteenth century. On the “down freight” runs his shallops frequently carried consignments of furniture destined for customers in the Chesapeake Bay area. At times Hollingsworth favored Trumble with Windsor orders, as for instance the “Round top Windsor Chairs @ 14/” and “One high back Do” at fourteen shillings that he purchased in 1772, or the “6 Sack back Chairs 11/2” and the “6 Fan do” purchased in 1786 (see Appendix).

Hollingsworth also purchased Windsors from another Philadelphia craftsman, Joseph Henzey (1743–1796), although the eight Windsor chairs shipped by Hollingsworth in 1765 to Mr. William Thomas of Annapolis and the dozen chairs each shipped at about the same time to Mr. William Lux, a Baltimore merchant, and a Mr. Thomas Campble [sic] were not supplied by Henzey. The young craftsman was just out of his apprenticeship in 1765, and there is no evidence he as yet had his own shop. The chairs were obtained from Trumble or still a third craftsman. The Windsor chairs made by the various Philadelphia shops were very similar and in most cases are distinguishable today only if they bear a brand.[18]

Francis Trumble’s business connections extended to the Clement Biddle Company of Philadelphia; again he provided chairs for the Chesapeake Bay trade. Six Windsors from his shop were charged against the accounts of Thomas Richardson and Company of Georgetown on the Potomac in January, 1774 (see Appendix). Four years earlier, in 1770, other chairs had been shipped to the same firm on board the schooner Lovely Lass. In this year, too, the letterbook of Clement Biddle and Company reveals that in reply to an inquiry by Thomas Contee, another merchant in the Georgetown area, current Windsor prices were quoted at ten to fifteen shillings, depending on the “fashion,” or style, of the chair. Two months previous to the inquiry, the company had shipped to Contee “2 arm chairs” which cost £1.10.00. The price indicates they were Windsors.[19]

Several consignments of goods from Clement Biddle and Company were shipped to Mr. David Crauford (Crawford, Cranford; ca. 1738–1801) of “uper Marlboro,” Maryland, a location on the upper reaches of the Patuxent River that had reasonable access to water transport. Windsors were included in each of three consignments received by Crauford in 1770. All told, twenty chairs were shipped, one group being described as having round backs and another as being “new fashion.” A partially illegible notation scrawled on one of the shipping accounts appears to indicate that Francis Trumble fabricated at least one group of these chairs. The Biddle trade, it would seem, was carried on exclusively by the water route. Their vessels sailed southward through Delaware Bay, around the Delmarva Peninsula, and then northward into the Chesapeake Bay. The water passage, though greater in distance, was probably no more costly than the Hollingsworth route, because overland transportation was considerably more expensive than water transportation.[20]

Trumble also exported Windsors to Charleston, South Carolina. On September 2, 1789, he shipped four dozen chairs to this port on board the ship Philadelphia. In December of the same year, fourteen dozen Windsors were sent to John Minnick on board the Charleston. An additional 116 chairs reached Minnick and James Raguet (Raggee) (1756–1818) aboard the Columbia in March of the following year. At the same time, thirty-nine Windsor chairs, two carts, and twenty-three wheelbarrows were consigned to the firm of Condy and Bryon (see Appendix). As early as 1766 the Charleston firm of Sheed and White had advertised the importation of “a large and neat assortment of Windsor Chairs” from Philadelphia which included:

high back’d, low back’d, sack back’d, and settees or double seated, fit for piazzas or gardens, childrens dining and low chairs. Also walnut [chairs] of the same construction.[21]

Not only Philadelphia merchants, but occasionally Philadelphia craftsmen, ventured into the expanding West India trade. The account book of Benjamin Randolph (1721–1791) indicates that he had interests in a number of voyages to the Caribbean, and his records of November 17, 1768, credit Francis Trumble with merchandise—probably Windsor chairs—to the extent of £10.16.00 for a “Voyage to Jamaica.” This was probably a reference to the voyage of the ship Diana, which left Philadelphia in November of 1768 and returned again the following May. The merchant Thomas Riché is known to have sent at least one consignment of chairs to the Island of New Providence in the Bahamas, and because he had made earlier furniture purchases from Trumble for the West India trade, it is likely that he again patronized this Philadelphia chair maker.[22]

Francis Trumble’s expanding export business required increasingly more workspace to fulfill these orders. Soon after his arrival in Philadelphia, Trumble rented his house from Nathaniel Allen, and by 1750 he was renting a three-story row house with a two-story kitchen and a joiner’s shop on the west side of Second Street between Market and Chestnut Streets from Israel Pemberton Jr. (1715–1779). On July 8, 1753, the house, apparently unoccupied at the time, was struck by lightning and severely damaged, an event that was of considerable interest to Benjamin Franklin, who had just two weeks earlier made a public appeal for information on such strikes. Franklin was in Boston at the time of the strike on Trumble’s house but received reports from his son William (1730–1813), who visited the site and gave his father a detailed account of the lightning’s course of travel. A month later, Pemberton submitted a report to the Philadelphia Contributionship, America’s first fire insurance company:

Israel Pemberton junr enformed the Company that his house in second street where Francis Trumble dwells was lately struck & Damaged by Lightening . . . the said House was Insured at 40/p ct. on accot of the Joyners business being carried on there which [was] now removed . . . .

As indicated, the severity of the damage caused Trumble to move, and Pemberton requested a new survey.[23]

Upon leaving Pemberton’s house, Trumble opened up his new shop “at the sign of the Scrutore, in Front-street, near the New-market Wharff, on Society Hill, Philadelphia . . . .” Slightly more than a year later, this was the location mentioned in an advertisement appearing in the Philadelphia Gazette. During the rest of his career, Trumble lived and worked on Society Hill, a section that extended south from Pine Street to near Old Swedes’ Church. In 1762 this area became part of Southwark, a new and rapidly growing district south the of the city that proved to be attractive to craftsmen. By 1773 the Philadelphia County Tax Assessment Ledger was listing twelve joiners and two turners in the district, in addition to Trumble, as well as other craftsmen who pursued such trades as shipwright, silversmith, and china maker.[24]

Trumble’s business expanded considerably during the late 1760s and early 1770s. In 1768 he purchased a 41 x 100-foot lot in the Dock Ward on the west side of Front Street between Pine and Cedar (or South) Streets from Joseph and Sarah (Powel) Potts. The following year, Trumble paid taxes on “2 Large Shops” on this site, as well as a dwelling house and two additional shops in Southwark; his other taxable property included four enslaved people, a horse, and two acres in Moyamensing. In newspaper advertisements in November and December 1775, his property was described in more detail. The Dock Ward property was his “Cabinet and Chair-store in Front-street near Pine Street,” while his Southwark property included his home with two lots lying between Second and George Streets: one lot was 23 x 256 feet and contained a “three story brick messuage or tenement, and lot or piece of ground thereto belonging, with the buildings and appurtenances”; the other was 80 x 256 feet “having sundry frame shops thereon erected.” Also described as lying between South and Shippen Streets and at 238 Second Street, Trumble’s Southwark property was just south of the New Market and in close proximity to his Dock Ward shops (figs. 10, 11). He also owned a lot on the north side of Catherine Street between Front and Second Streets, which he had acquired in 1774. These listings suggest that Trumble operated one of the larger furniture businesses in Philadelphia at the time—no other woodworker is known to have had more than a single shop.[25]

At the same time, Trumble was frequently in debt, suggesting that his business was overextended. He had previously been sued for indebtedness on a number of occasions, but one instance in 1775 was particularly intense and occurred when his shop appears to have been operating at maximum capacity. In July of that year, merchants Hartley and Mason sued Trumble for outstanding funds due from his purchase of over £300 worth of mahogany, and separately Samuel Barker also pressed charges for monies owed. As Trumble had done many times previously, he evaded further prosecution by promising to pay; also, as he had done before, he defaulted on these promises. On November 15 Sheriff William Dewees announced the sale the following week of two of Trumble’s Southwark properties, both lying between Second and George Streets, one lot measuring 23 x 256 feet and another measuring 80 x 256 feet with “sundry frames shops thereon erected.” Their dispute continued in retorts from both men published in newspapers, each accusing the other of defamation.[26]

Perhaps in response to a perceived injury to his reputation, Trumble placed an advertisement on December 27, 1775, that demonstrates the extraordinary scope and scale of his business:

FRANCIS TRUMBLE

Has for SALE, at his Cabinet and Chair-store in Front-

street near Pine Street,

EIGHTY mahogany chairs, carved and plain; 30 tea tables; 20 dining tables; 6 desks; chests of drawers; desks and book-cases; dressing tables; writing tables; card tables; pembroke tables; tea stands; tea trays; tea and decanter boards; bedsteads and cradles. The whole made of seasoned mahogany, and good workmanship. Twelve hundred Windsor chairs; walnut chairs and cradles; settees; painted bedsteads; and tables; sacking bottoms; chairs and stools for counting-houses; flat and round hard wood rulers; sea chests; walking sticks; lime squeesers; rolling pins; sugar mallets; bedstead and cloak pins; 20,000 feet of mahogany board, and plank, fit for immediate use; poplar, oak, and New-England pine plank; oak posts, from 12 to 18 feet long. An assortment of low price brass handles for chests of drawers; brass locks, and lifting handles, for desks; brass knockers for doors; sash screws, and curtain rings; coffin handles, plates, and letters; chest hinges; snipe bill T hinges; augres; socket heading chissels, and gouges; scale beams; iron boxes; shoemaker’s pinchers; awl handles, and blades; scupper nails; bed screws; chest handles. Also, the Times of three Dutch Servant men, who have each near four years to serve.

WANTED. Several journeymen spinning-wheel makers; 5000 feet 2 inch poplar plank; 2000 feet inch ditto; 2000 half inch ditto; 1000 feet walnut plank, 2 1/4 inches thick; 1000 feet 1/2 inch ditto; 1000 feet of white oak joint stuff for tables; 40 setts of poplar stuff for bedsteads; 4 cords of white oak butts, clear of knots, in 4 feet lengths; 40,000 hickory sticks for Windsor chairs; 500 setts of stocks and rims for spinning wheels. Any person who can supply me with the above, by calling on me at my house, in Second-street, Southwark, will oblige, their friend, FRANCIS TRUMBLE.[27]

It is obvious that the vast quantity of furniture made in Francis Trumble’s shop could not have been fabricated by one man. Trumble is known to have taken on apprentices, and he probably employed journeymen. As discussed above, Trumble was assisted in his business soon after his arrival in Philadelphia with the services of a servant, who was noted to be a joiner. From 1749 to 1751 Trumble made purchases of fabric and suits that were delivered to four individuals who may have had ties to his shop, whether as servants, apprentices, journeymen, or contract workers. On February 6 and 9, 1750, Trumble purchased from Thomas Penrose two suits “of Broad Cloth wt Trimmings” each costing £8.10.00, the first delivered to John Elton (1725–1775) and the second to Samuel Harding (d. 1758). Elton was a joiner and turner who is known to have made Windsor chairs in 1757; Harding was one of the most significant Philadelphia carvers of the 1750s, whose commissions included architectural ornament for the Pennsylvania State House. While a standard obligation of a master was to provide a new suit—frequently referred to as a “freedom suit”—for an apprentice who had completed his training, the purchase of a coat by cabinetmaker Benjamin Randolph for carver Hercules Courtenay (circa 1744–1784) in 1766 indicates that such provisions were also made to those who had already completed their apprenticeships. Trumble also purchased fabric from Penrose that was delivered in 1749 to Jacob Hankey (Henke; fl. 1750–1789), identified as a turner in an advertisement a year later, and in 1751 to Jacobus Van Osten (1716–1796), a Dutch immigrant about whom little else is known. In 1750 a committee of Friends of the Philadelphia Monthly Meeting apprenticed Seymour Wood “to Francis Trumbell to Learn the Trade of a Joiner . . . .” In a very short time, however, the lad ran away to sea.[28]

Trumble’s next known apprentice was William Coyle, who was identified as such in a 1763 court hearing. In the records of the Philadelphia Monthly Meeting, Southern District, John Priestly is listed as “apprentice to Francis Trumble” and “Disowned” in 1773. Priestly’s training with Trumble probably began in 1767, when the Philadelphia Monthly Meeting records report on the case of Mary Priestly and note that members had “lately placed her son John apprentice with a suitable Master & Trade.” Jonathan Guy also worked in Trumble’s shop around the same time: in 1768, when he escaped from the Philadelphia workhouse, he was noted to be “a servant to Francis Trimble” and “a joiner and chairmaker by trade.” Another craftsman known to have been bound to Trumble was Joseph Tom, “a poor boy” who was apprenticed to learn the trade of turner and Windsor chair maker for a period of four years beginning on February 12, 1771. The following year, John Letchworth apprenticed with Trumble and later became a well-known Windsor chair maker.[29]

In 1773 three apprentices were bound to Trumble: David Clark, for two years; James Venall, for four years; and John Gally, for eighteen months. Venall was assigned to Trumble after cancellation of an indenture of servitude to Benjamin Fuller, but apparently he did not prove satisfactory because three months later he was assigned back to Fuller to learn the trade of mariner. John Gally, probably the same individual as one identified as Adam Galler/Galer, was apprenticed to Trumble to learn “the art and mystery” of Windsor chair making. While his term was to be a year and a half, he left after fourteen months and set up a shop in New York City. By 1775 Trumble had acquired three servants. His advertisement from that year offered for sale “the Times of three Dutch Servant men, who have each near four years to serve.” At the same time Trumble informed the public that he wanted “several journeymen spinning-wheel makers” in addition to “500 setts of stocks and rims for spinning wheels.” It would seem that he anticipated expanding into still another area of furniture production. In 1785 William Brown apprenticed to Trumble, probably to learn cabinetmaking because eleven years later he, in turn, took an apprentice to learn the “Art & Mystery of a Cabinet Maker.” Other men who may have worked in the shop include James Davis, whose master in 1769 was William Cox, who received money from Levi Hollingsworth on Trumble’s behalf in 1782.[30]

An integral member of the shop from the mid-1760s onward was Trumble’s son-in-law, Thomas Mushett (d. after 1806). Trumble’s family life underwent several changes in the 1760s. His wife of twenty-four years, Sarah (Catchpool), died on October 18, 1762. Seven years later, Trumble married Hannah Gardner (ca. 1732–1798) in the first Presbyterian Church of Philadelphia, indicating he had left the Quaker faith. This is confirmed in the membership list of the Philadelphia Monthly Meeting, Southern District, in which alongside Trumble’s name is the notation “Has no right amongst Friends.” However, in 1798, when Francis and Hannah died less than a month apart, both are recorded in the Quaker burial records, suggesting that he reaffirmed his Quaker beliefs before the end of his life. With his first wife, Trumble had had three children, Sarah (1740–1806), Francis, who died in infancy in 1745, and Hester. In 1764 Trumble’s daughter Sarah married Thomas Mushett, who shared many interests with his father-in-law, both social and professional. As recorded in the diary of Jacob Hiltzheimer (1729–1798), Trumble and Mushett were frequently in attendance at various convivial gatherings in the late 1760s and early 1770s that included distinguished figures such as master builder Robert Smith (1722–1777), Joseph Fox (1709–1779), Samuel Morris (1734–1812), and James Webb Jr., the sheriff of Lancaster County. Some of these festivities took place at Robert Smith’s Buck Tavern in Moyamensing, south Philadelphia, which from 1773 to about 1779 was run by Mushett or his father of the same name (fig. 12). By the 1780s Mushett’s primary occupation appears to have been chair maker. Identified as such in a 1782 tax list and the 1790 U.S. Federal Census, Mushett was most likely closely involved with Trumble’s business. He is known to have collected payment from merchants on Trumble’s behalf on at least two occasions and, as indicated by tax lists, Mushett and Trumble lived in and owned adjoining properties in Southwark, Dock Ward, and New Market during the 1770s and 1780s. Their close relationship continued throughout Trumble’s life. Upon Trumble’s death in 1798, Mushett was one of the administrators of his estate and is listed at Catherine Street, between Front and Second Streets, Trumble’s last known address.[31]

After the public skirmish between Trumble and the sheriff in late 1775, Trumble’s reputation seems to have remained intact, since the Pennsylvania Assembly purchased two tables and twelve chairs from Trumble in March the following year. These, along with the rest of the furnishings of the State House (fig. 13), were removed or destroyed during the British occupation of Philadelphia between September 1777 and June 1778. David Evans (1748– 1819), a cabinetmaker whose daybook is the only complete Philadelphia account book to survive for the late eighteenth century, commented freely in its pages on life and events in the city. An abrupt note appears in the accounts under the date September 26, 1777: “The British Army march’d in this City.” Eight days later Evans recorded, “A Very Heavy Battle at Germantown between the British & American Troops it being the 7th Day of ye week.” The coffin-making business was brisk and the potter’s fields were soon filled. The British remained in control of the city until their departure in June 1778. During the occupation, Trumble and his family relocated to West Chester (then called Turk’s Head), a small settlement nearby in Pennsylvania that soon was to become the seat of a newly reorganized Chester County. Tax records for Goshen Township, of which West Chester was originally a part, document that Trumble paid taxes in 1779 and 1780. There is no evidence that chairs were made by Trumble in Turk’s Head, but the surviving chairs of Sampson Barnet, who lived in Goshen Township at the same time, bear a remarkable similarity to Trumble’s work, and it is possible that Trumble brought some of his products to the area for either personal use or sale.[32]

However, Trumble was able to spring back into action when the British troops evacuated the city and the Continental Congress reconvened in the State House in late June 1778 only to find there was no seating for the delegates. As discussed by Evans in 1964, the minutes of the Supreme Executive Council for July 21, 1778, note that “The Council Room in the State House being now cleansed, & in order for the reception of the Council, except only that there are no Chairs therein, Ordered, That the Secretary procure eighteen Windsor Chairs for the Council Room.” These were undoubtedly made by Trumble since on August 20 the Council recorded payment to him for nineteen Windsor chairs in the amount of £64.02.06, or £3.07.06 per chair. A week later Trumble was paid £84.15.00 for twenty-eight chairs for the Assembly Room, just over three pounds per chair, and in November 1778 he was paid sixty pounds for twenty additional chairs for the Assembly Room, at three pounds per chair. Some of these must have been completed by August 6, when the French Minister Conrad Alexandre Gérard was formally entertained. The following day Gérard made a report that included a hand-drawn plan of the Assembly Room at that event. There were, according to Gérard, two large chairs and thirty-four additional chairs. The larger chairs were upholstered, one for the president of Congress and the other for Gérard.[33]

Trumble supplied several different Windsor styles to the State House during this period. Sack-back Windsors are pictured in Robert Edge Pine’s painting of The Congress Voting Independence, July 4th, 1776, which was finished at his death in 1788 by Edward Savage (fig. 14). These Windsors have bamboo-turned legs, however, while the only sack backs known that bear Trumble’s brand, or that of any other Philadelphia maker, have balusterturned legs. Since Pine was not an eyewitness to the scene he painted, the accuracy of the details can be questioned. As cited by William MacPherson Hornor, the chairs supplied by Trumble from August to November of 1778 included “12 Round Top Scrol arm Chairs at 7/6” for a total of £40.10.00 as well as “Ditto plain do do,” “Low back,” and “Sack back Windsors.”[34]

During the British occupation of Philadelphia, and probably for a few years following, Trumble supplemented his income with the operation of an inn. He advertised on August 25, 1778, that he had rented the Turk’s Head tavern in Goshen Township, Chester County, and had “Provided Every necessary to keep an Inn or Publick House.” Since Trumble was at this time busy fulfilling orders for the State House, it is likely he remained in Philadelphia while his family continued to reside in Chester County. A later account of Trumble’s apprentice, John Letchworth, notes that “[d]uring this eventful period, a part of his master’s family being in the country, John had to be there and in the city alternatively, and the transition was sometimes attended with difficulty.” By 1782 the Turk’s Head tavern had a different owner, and with the war in its final stages, Trumble’s family probably moved back to Philadelphia around this time. Trumble’s export business continued to flourish during the next decade. Several large consignments are recorded to mercantile enterprises such as those of Levi Hollingsworth, Clement Biddle and Co., and Coxe and Frazier (see Appendix).[35]

Among these consignments was a shipment bound for Asia in 1789 containing eight dozen of Trumble’s Windsor chairs. The voyage began when the ship Canton, owned by Constable, Rucker and Company of New York was chartered by Isaac Hazlehurst and Company of Philadelphia for a voyage to India and China to obtain a rich cargo of teas, spices, textiles, chinaware, and more. Among the craftsmen enlisted to provide services or goods were: Edward Cutbush, carver; John Davis, upholsterer; John Cornish, turner; and Francis Trumble, chair maker. Thomas Truxton, also of Philadelphia, was the ship’s captain. The Canton set sail on or about December 12, 1789, for Bombay and China. Short stops would have been made en route to acquire fresh foodstuffs, water, and other needed supplies, as well as to negotiate any sales possible of the goods on board. An important destination was reached when the Canton sailed into port on March 30, 1790, at Cape of Good Hope, South Africa. Here Captain Truxton negotiated the sale of more than 158,000 feet of the pine plank, boards, and scantling on board and the eight dozen Windsor chairs consigned by Trumble, described and priced as follows:

4 [Doz] Plain Dining Chairs 70/. 14.0.0

1/2 " Scroled Arm D[itt]o 150/ 3.15.0

1/2 " Plain Armed D[itt]o 135/ 3.7.6

1/2 " Bamboo Chairs painted Mahogany & tipt 110/ 2.15.0

1/2 " D[itt]o Plain 100/ 2.10.0

1/2 " Scrolled Dining Chairs 75/ 1.17.6

1 " Common D[itt]o 3.10.0

1/2 " D[itt]o D[itt]o 60/ 1.10.0

Of this group, the five dozen chairs described as “Plain” or “Common” dining chairs were fan-back chairs with plain crest pieces. The half dozen “Scrolled Dining Chairs,” priced slightly higher, would have had the crest tips carved in scrolls. A half dozen dining chairs priced slightly less than all the others may have had seven-spindle backs rather than nine-spindle backs. The scrolled-arm and plain-arm chairs were knuckle-arm and flatarm sack-back chairs. Of the newest design were the one dozen “bamboo” chairs, half of them painted mahogany color and “tipt” (the bamboo “creases” picked out in a contrasting color) and the rest simply plain painted. The complete lot of chairs sold for 180 Spanish dollars, a common international medium of exchange in this period.[36]

In 1790 Trumble turned seventy-five years old, and several sales of his property in the ensuing years indicate his business was dwindling. His “Cabinet and Chair-store” on Front Street in the Dock Ward, which he had purchased in 1768, was sold by the sheriff for £417 in 1791, the property consisting of “five frame buildings & a workshop” at the time. Two years later the sheriff advertised the sale of two lots of Trumble’s on Catherine Street, one of which Trumble had acquired in 1774. Either the sale did not take place or only one lot was sold, since this was the location of Trumble’s last residence and shop. In 1796 he sold an 80 ¤ 128-foot piece of land that was part of lots adjoining his house on Second Street between South and Shippen Streets, also in Southwark, to Anthony Morris and Edward Bonsell for £1,240. Part of this property was also offered for sale by the sheriff the same year. Trumble vacated this location in March of 1798 when he announced that he was going to move to “his Windsor Chair Shop, to the north side of Catherine Street, between Front and Second streets, where the business will be carried on as usual.” Prior to this move, he advertised the sale of a “Small FRAME SHOP” at his Second Street location, as well as “A TURNER’S WHEEL LATHE/ Several work benches; sundry pieces of cabinetwork unfinished; also, a quantity of mahogany and walnut chair and table feet, bannisters, &c. Mahogany finnears, carved work for furniture, &c.”[37]

As indicated by this advertisement, Trumble was still a cabinetmaker as well as a Windsor chair maker. The mention of “sundry pieces of cabinetwork unfinished,” “Mahogany finnears,” and the “carved work for furniture” is the only known surviving evidence that Trumble was producing fine furniture during the Federal period. The fact that his shop had been equipped with at least one “Turner’s Wheel Lathe” reveals that Trumble had not relied on the services of a turner’s shop for his Windsor parts, but rather he had produced them in his own establishment. Since he was continuing in the Windsor chair-making business on Catherine Street, he undoubtedly had at least one other lathe.

Trumble’s location on Catherine Street was not of long duration, for he died on August 11, 1798, at the age of eighty-two years. He was buried in the Quaker burial ground, as was his wife Hannah, who followed him in death less than one month later. He apparently died intestate, for no will is recorded in Trumble’s name in the Philadelphia city and county records. The grant to administer his estate was conveyed to:

Thomas Musket [Mushett] of Southwark Gent:

John Letchworth of the City of Philada Windsor Chairmaker

Thos Annesley of Southwark Gent:[38]

The inventory of his estate indicates that Trumble died while still a relatively active cabinetmaker and Windsor chair maker (figs. 15, 16). Only the tops of two pages survive, the first seemingly the contents of his household and the second of his shop. The furnishings of his home included both fine and less expensive forms such as: a dining table, tea table, and looking glass, all of mahogany; one high-post and two low-post bedsteads (one for a servant); three “Armed,” four “Oval back,” and five unspecified Windsor chairs; and two small bureau tables. His shop contained fifty-eight “Oval back” and five “Dining” Windsor chairs, their coatings variously described as “not Varnishd or pinkt,” “primed only,” “finished Green,” and “Mahogany Colour.” He also had 108 “Bows for Chairs (in the Ruff)” and seventy-five “Top Rails” (for the crests of fan-back chairs). Cabinetware comprised frames for breakfast and card tables, square and round pine tables, mahogany dining table tops, and rails for field bedsteads. In addition to tools for grinding and mixing paints, a number of woodworking tools—such as drawing knives, hand, tennant and frame saws, hatchets, a maule, a frow, wedges, adzes, and planes—are listed. Not in the surviving fragments of the inventory, but mentioned in his 1775 advertisement, are carving tools. A number of such tools were excavated at the site of his Front Street shops and include gouges, chisels, gravers, and a rasp that are thought to date from Trumble’s occupancy from 1768 to 1791.[39]

Five years before he died, Trumble sold a number of chairs to the first U.S. secretary of state, Thomas Jefferson. Jefferson’s memorandum books record a payment of twenty dollars to Trumble for twelve chairs on April 9, 1793, followed by an additional $1.40 for painting six of these. On the same day, Jefferson paid for portage of “8 loads of furniture to waterside,” indicating that some of these may have been shipped to his Virginia estate, Monticello. Over a course of fifty-plus years, Trumble had gone from death row in London’s Newgate Prison to supplying wares to one of early America’s most famous citizens. No doubt much of his change in fortune was due to his own talents, ingenuity, and entrepreneurship. But Philadelphia, with its burgeoning population, access to shipping routes, and considerably fewer artisans compared to London, provided an ideal setting for someone with Trumble’s resourcefulness.[40]

England & Wales, Quaker Birth, Marriage, and Death Registers, 1578–1837, Ancestry.com, https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/7097/, accessed May 22, 2022 [original data: The National Archives, Kew, England; General Register Office: Society of Friends’ Registers, Notes and Certificates of Births, Marriages and Burials; Class: RG 6, Piece 1213: Monthly Meeting of Woodbridge, Beccles (1653–1775), Piece 1608: Monthly Meeting of Woodbridge, Beccles: Marriages (1658– 1696) and Piece 0328: Quarterly Meeting of London and Middlesex: Births (1708–1747)]. Trumble’s father was born in Gateshead, Durham, in 1686 (England, Select Births and Christenings, 1538–1975, Ancestry.com, https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/9841/, accessed May 22, 2022). Apprenticeship papers indicate that Trumble began his apprenticeship in 1730, but later court testimony records he began at age twelve in 1727 (UK, Register of Duties Paid for Apprentices’ Indentures, 1710–1811, Ancestry.com, https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/1851/, accessed May 22, 2022 [original data: The National Archives of the UK (TNA), Kew, England; Collection: Board of Stamps: Apprenticeship Books: Series IR 1; Class: IR 1; Piece: 13, p. 164)]; Colchester People: The John Bensusan Butt Biographical Dictionary of Eighteenth-Century Colchester, 2nd ed., edited by Shani D’Cruze, 3 vols. (N.p.: privately printed, 2010), 1: 409.

“The Justicing Notebook of Henry Norris: 1738–9,” in Justice in Eighteenth-Century Hackney: The Justicing Notebook of Henry Norris and the Hackney Petty Sessions Book, edited by Ruth Paley (London: London Record Society, 1991), pp. 46–56, no. 302; British History Online, http://www.british-history.ac.uk/london-record-soc/vol28/pp46-56, accessed May 22, 2022. “Trial of Francis Trumble,” July 1739, t17390718-10, Old Bailey Proceedings Online, version 8.0, https://www.oldbaileyonline.org, accessed May 13, 2022.

“Trial of Francis Trumble.” Francis Trumble Sr. was master of the Felton, which was found damaged and abandoned with its full load of timber from Norway off the coast of Scotland on April 30, 1739; a later report noted that Trumble was among the five who were drowned in the event (Ipswich Journal, May 19, 1739, pp. 2–4).

“Ordinary of Newgate’s Account,” August 1739, OA17390803, Old Bailey Proceedings Online. “Trial of Francis Trumble” and “Ordinary of Newgate’s Account;” “Introduction,” in Justice in Eighteenth-Century Hackney, pp. ix–xxxiii, in British History Online, http://www. british-history.ac.uk/london-record-soc/vol28/ix-xxxiii, accessed May 23, 2022; Ipswich Journal, July 28, 1739, p. 4, and September 15, 1739, p. 1.

Carl and Jessica Bridenbaugh, Rebels and Gentlemen: Philadelphia in the Age of Franklin (New York: Oxford University Press, 1962), pp. 3, 230.

Account Book of Solomon Fussell (July, 1738–May, 1749), p. 78, Stephen Collins Collection, Library of Congress, Washington D.C. (cited hereafter as Account Book of Solomon Fussell); William MacPherson Hornor Jr., Blue Book: Philadelphia Furniture (Philadelphia: privately printed, 1935), pp. 57–59.

American Weekly Mercury, May 28, 1741, p. 3; Nathaniel Allen Ledgers (1732–1757), p. 164, collection Am.0073, Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pa. (cited hereafter as HSP); Records of the Contributionship Fire Insurance Company of Philadelphia reveal at least three instances of craftsmen living and working in adjacent buildings: the company insured “a house for William Savery . . . where he dwells [and] a Chairmakers Shop [which] Joins the Kitchen” in 1772; Charles Ewald had “his Joiners Shop & his House & Kitchen situate on the South side of Sassafras Street” insured in 1760; and, in 1765, Leonard Kessler paid his “Deposit Money for Insuring his dwelling House & back buildings including a “Joiners Shop.” The Contributionship Companies (Philadelphia), Surveys Book No. 1 (1768–1794), p. 42, and Journal (1756–1768), microfilm, Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera, Winterthur Library, Winterthur, Del. (cited hereafter as Downs Collection).

Nathaniel Allen Ledgers (1732–1757), p. 164.

Samuel Powel Jr. Receipt Book (1744–1747), Powel Family Papers, vol. 17, Library Company of Philadelphia (cited hereafter as LCP); Samuel McCall Sr. Account Book (1743-1749), collection Am.9218, HSP. The chairs purchased by McCall cost twenty-five shillings each. Mahogany chairs purchased from the Trumble shop by another customer seven years earlier cost thirty-nine shillings each. Harrold E. Gillingham, “New Delvings in Old Fields: Furniture Ventures from Philadelphia,” Antiques 29, no. 6 (June 1936): 261. This difference in price would tend to indicate that McCall’s chairs were not mahogany. Rush-bottomed chair prices are quoted in the Account Book of Solomon Fussell and are less than one pound each, while Windsors are noted as costing ten to fifteen shillings; Clement Biddle and Co. Letterbooks, vol. 1 (1769–1770), collection Am.9180, HSP.

Letterbook 1739–1746, Powel Family Papers, vol. 2, collection 1582, LCP.

Both Thomas and Stephen Paschall did a brisk business in mending and making tools for Philadelphia craftsmen. Thomas Paschall (1713–1766) Ledger and Stephen Paschall (1735–1774) Ledger, Paschall Hollingsworth Collection, collection 0474, HSP; Account Book of Solomon Fussell; Thomas Penrose Cashbooks, vol. 3, collection Amb.39folio, HSP. As noted in her 1964 article, Evans is indebted to Mr. Arthur W. Leibundguth for bringing to her attention this and many early manuscript references to Francis Trumble and others in the furniture craft.

The nature of these purchases was not disclosed. John Smith Account Book (1751–1756), p. 20, LCP; John Hatkinson Ledger (1748–1758), collection Am.076, HSP; Owen Jones Daybook, vol. 1 (1759–1761), Jones Family Papers, collection 1301, HSP.

Pennsylvania Gazette, August 8, 1754, p. 2.

Francis Trumble, Bill to the Estate of Thomas Davies, and, Francis Trumble, Bills to Thomas Wharton, Wharton Family Papers, Box 1697–1756, folders 1754–56, collection 708A, HSP; Gillingham 1936: 261; Thomas Riché Letterbooks (1748/49–1755), Thomas Riché Records, collection Am.9261, HSP.

Inventory of personal estate of William Fishbourne, June 22, 1742, Will Index Book F, Municipal Archives, City of Philadelphia, Office of the Register of Wills; Pennsylvania Gazette, August 25, 1748, p. 3; Jedediah Snowden, Bill to John Reynell, series 1, vol. 17, and, Mary Coates Receipt Book (1748–1759), series 5, vol. 119, collection 0140, Coates and Reynell Family Papers, HSP.

Harrold E. Gillingham, “The Philadelphia Windsor Chair and Its Journeyings,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 55, no. 4 (1931): 304. The previous year Story had also purchased from Trumble “a Mahogany Tea Table” at £4.05.00; Garrett Meade Receipt Book (1759–1762), series 3, vol. 70, collection 0175, Ferdinand J. Dreer Autograph Collection, HSP; Nancy Goyne Evans, American Windsor Chairs (New York: Hudson Hills Press in association with the Henry Francis du Pont Winterthur Museum, 1996), pp. 69, 84.

For a full discussion of these designs and their production by Trumble, see Evans, American Windsor Chairs, pp. 83–84, 86–87, 91–93, 96–103. See also Nancy Goyne Evans, “Frog Backs and Turkey Legs: The Nomenclature of Vernacular Seating Furniture, 1740–1850,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Milwaukee, Wis.: Chipstone Foundation, 1996), pp. 20–27; David R. Pesuit, “Structure, Style, and Evolution: The Sack-Back Windsor Armchair,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Milwaukee, Wis.: Chipstone Foundation, 2005), pp. 63–118; Nancy A. Goyne [Evans], “Francis Trumble of Philadelphia: Windsor Chair and Cabinetmaker,” Winterthur Portfolio 1 (1964): 231, 237–238; Charles Santore, The Windsor Style in America, 2 vols. (Philadelphia: Running Press, 1981-1987), 1: 97–98, 195, 2: 95, 120, 189; and Hornor, Blue Book, pp. 259, 300, 302, 309.

Francis Trumble, Bill to Levi Hollingsworth, November 26, 1772, Hollingsworth Family Papers (1715–1882), series 2, box 250, folder 4, collection 0289, HSP; Francis Trumble, Bill to Levi Hollingsworth, box 17 (Hill-Hug), Historical Society of Pennsylvania Society Small Collection (1769–1975) , collection 0022B, HSP.

Clement Biddle (1740–1814) Letterbooks, vol. 1, collection Am.9180, HSP.

Clement Biddle Letterbooks, vol. 1, June 27, August 28, and October 8, 1770.

Gillingham, “The Philadelphia Windsor Chair,” pp. 327, 329–30. South Carolina Gazette, June 23, 1766, as quoted in Alfred Coxe Prime, The Arts & Crafts in Philadelphia, Maryland, and South Carolina, 1721–1785, 2 vols. (Philadelphia: Walpole Society, 1929), 1: 188–89.

Benjamin Randolph Account Book (1767–1787), December 27, 1768, New York Public Library, from microfilm copy, Downs Collection; Port of Philadelphia Bills of Lading, collection 0515, HSP.

Trumble was living and working on Second Street as early as 1750, when on July 19th of that year an advertisement of John Davis noted that he was “At Francis Trumble’s Joyner, in Second Street, opposite to the Black-Horse Alley.” This was the location of Pemberton’s property. Davis’s advertisement also includes “N.B. The said Francis Trumble, has all sorts of ready made furniture,” also cited in Evans, “Francis Trumble of Philadelphia,” p. 225, fn. 14; Pennsylvania Gazette, July 19, 1750, p. 6, June 21, 1753, p. 2, and July 12, p. 2; “To Benjamin Franklin from William Franklin, 12 July 1753,” Benjamin Franklin Papers, Founders Online, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C., https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-05-02-0002, accessed November 15, 2022 [original source: The Papers of Benjamin Franklin, vol. 5: July 1, 1753, through March 31, 1755, edited by Leonard W. Labaree (New Haven, Ct.: Yale University Press, 1962), pp. 4–7]. “From Benjamin Franklin to William Franklin, 23 July 1753,” Benjamin Franklin Papers, Founders Online, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C., https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-05-02-0006, accessed November 15, 2022 [original source: The Papers of Benjamin Franklin, vol. 5: July 1, 1753, through March 31, 1755, edited by Leonard W. Labaree (New Haven, Ct.: Yale University Press, 1962), pp. 15–16.]; The Contributionship Companies, Records of the Contributionship Fire Insurance Company of Philadelphia, Journal (1756–1768), p. 27.

The “New-market Wharff” probably was located at Pine Street. J. Thomas Scharf and Thompson Westcott, History of Philadelphia 1609–1884, 3 vols. (Philadelphia: L. H. Everts, 1884), 1: 620; Philadelphia Gazette, August 3, 1754, as cited in Prime, Arts & Crafts in Philadelphia, Maryland and South Carolina, p. 184; Municipal Archives, City of Philadelphia, Department of Records. Trumble is noted as living on Society Hill as early as October 1753: see Pennsylvania Gazette, October 11, 1753, p. 1.

“John Clement Stocker House,” Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS), HABS No. PA-1068, National Park Service; Pennsylvania Historical & Museum Commission, Records of the Office of the Comptroller General, RG-4; “Tax & Exoneration Lists, 1762–1794 (Southwark), microfilm roll: 332,” Pennsylvania, U.S., Tax and Exoneration, 1768–1801, Ancestry.com, https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/2497/, accessed June 15, 2022; Pennsylvania Gazette, December 27, 1775, p. 3; University of Pennsylvania Archives, Mapping West Philadelphia: Landowners in October 1777, ref. r. EF 26.211, https://maps.archives.upenn.edu/ WestPhila1777, accessed November 1, 2022.

Pennsylvania Gazette, November 15, 1775, p. 1; Pennsylvania Journal, or, Weekly Advertiser, November 22, 1775, p. 3; Dunlap’s Pennsylvania Packet, or, the General Advertiser, November 27, 1775; Pennsylvania Gazette, December 27, 1775, p. 3. Trumbull had been taken to court on numerous occasions during the 1740s, 1750s, and 1760s, presumably over his failure to pay his debts. These cases included those brought by joiner Thomas Maule in March 1749, merchant Joshua Howell in March 1754, carver Samuel Harding in June 1754, John Michael Koss in September 1756, Vincent Gilpin in 1762, merchant Blair McClenachan in September 1765, Robert Wills and Samuel Jackson in September 1766, the same Samuel Jackson in March 1767, Benjamin Armitage in March 1767, Andrew Doz in March 1768, Elisha Lawrence in December 1768, Martin Christie in June 1769, William Huston in March 1770, Samuel Barker and William Huston in December 1770, John Jones in March 1771, Thomas McKim in March 1773, Ludwig Bitting in July 1775, Samuel Barker in July 1775, Mason and Hartley in September 1787, Tench Francis in December 1797, Penrose and Storey, n.d., and William Peters, n.d. Less frequently, Trumble was the plaintiff, as seen in the cases he brought against John Rowan in September 1745, John Hill in 1750, John Michael Koss in September 1756, Jonathan Guy in December 1767, William Thompson in December 1786, Thomas Procter in March 1788, and Thomas Wright in January 1791. See Pennsylvania, Court of General Sessions, Pennsylvania and Philadelphia Court Records, collection 3462, HSP; Robert Restalrig Logan, R. R. Logan Collection of John Dickinson Papers, collection 0383, HSP; Pennsylvania Courts, Pennsylvania Courts Dockets, collection Am.30923, HSP.

Pennsylvania Gazette, December 27, 1775, p. 3.

Thomas Penrose Cashbooks, vol. 3, collection Amb.39folio, HSP; William Fisher Receipt Book (1752–1757), Frank M. Etting Collection (1558–1917), box 78, collection 0193, HSP; Luke Beckerdite, “Brian Wilkinson, Samuel Harding, and Philadelphia Carving in the Early Georgian Style,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Milwaukee, Wis.: Chipstone Foundation, 2021), pp. 120–165; Beatrice Garvan, “Hercules Courtenay,” in Philadelphia: Three Centuries of American Art, Philadelphia Museum of Art, April 11–October 10, 1976 (Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1976), pp. 111–12 (the authors thank Luke Beckerdite for this reference); Pennsylvania Gazette, May 10, 1750, p. 3; Philadelphia Yearly Meeting of the Religious Society of Friends, Minutes of the Monthly Meeting of June 31, 1750, Nineteenth-Century Transcript of the Minutes of the Philadelphia Monthly Meeting (1745–1755), vol. E-4, Philadelphia City Archives.

The King vs. Peter McDowel, March 21, 1763, Pennsylvania, U.S., Oyer and Terminer Court Papers, 1757–1787, Ancestry.com, https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/2385/, accessed December 20, 2022; Philadelphia Monthly Meeting, Southern District, “Membership List, 1773–1784,” 4th Month [April], 28, 1773, and Philadelphia Monthly Meeting, “Minutes, 1765–1771,” April 24 and 26, 1767, U.S., Quaker Meeting Records, 1681–1935, Ancestry.com, https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/2189/, accessed November 22, 2022; Pennsylvania Chronicle, and Universal Advertiser, April 25, 1768, p. 101; Municipal Archives, City of Philadelphia, Department of Records, Bonds of Indemnity and Memorandum of and Indentures of the Poor (1751–1797), from microfilm, Downs Collection; “Some Account of John Letchworth,” John Letchworth Papers (1755–1870), H.C.MC-1198, Haverford College Library, Haverford, Pa.

The American Philosophical Society (Philadelphia), Book of Record of Indentures of Individuals, bound as apprentices, servants &c and of German & other Redemptioners in the office of the Mayor of the City of Philadelphia from October 3d 1771 to Oct 5th 1773, from microfilm, Downs Collection; “Record of Servants and Apprentices Bound and Assigned Before Hon. John Gibson, Mayor of Philadelphia, December 5th 1772–May 21, 1775,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 34 (1910): 116; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Indentures, 1771–1773, Ancestry.com, https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/4274/, accessed December 29, 2022; Pennsylvania Gazette, December 27, 1775, p. 3; Joel Zane Receipt Books (1761–1773) , collection Am.949, HSP; Receipt Book, October 14, 1782, Hollingsworth Family Papers, vol. 325, collection 0289, HSP.