David Mack, Spring Hill, Florida, 2022. (Photo, Carver Mostardi.)

The power of pottery: a grandmother educates her grandchild about the legacy of Madame C. J.Walker at Baltimore’s Artscape Festival, Baltimore, Maryland, 2006. (Photo, David Mack.)

Elijah McCoy, face pot, David Mack, Spring Hill, Florida, 2006. Stoneware. H. 24". (Photo, Carver Mostardi.)

Madam C. J. Walker, face pot, David Mack, Spring Hill, Florida, 2010. Stoneware. H. 25". (Photo, Carver Mostardi.)

George Washington Carver, face pot, David Mack, Spring Hill, Florida, 2012. Porcelain. H. 13 1/2". (Photo, Carver Mostardi.)

The Three Faces of Martin Luther King Jr., face pot, David Mack, Henderson, Nevada, 2004. Stoneware. H. 9Q 15/16”. (Photo, Carver Mostardi.)

Crispus Attucks, face pot, David Mack, Spring Hill, Florida, 2010. Stoneware. H. 13". (Photo, Carver Mostardi.)

Harriet Tubman, face pot, David Mack, Spring Hill, Florida, 2006. Stoneware. H. 17". (Photo, courtesy of the author.)

Sojourner Truth, face pot, David Mack, Spring Hill, Florida, 2011. Stoneware. H. 14". (Photo, Carver Mostardi.)

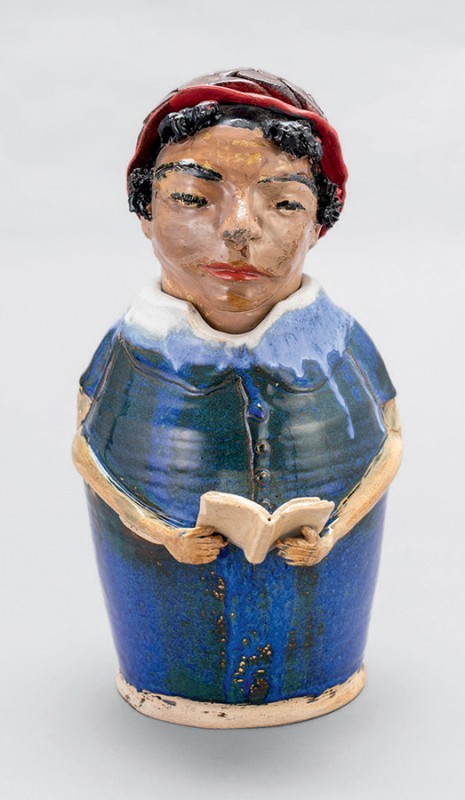

Phillis Wheatley, face pot, David Mack, Spring Hill, Florida, 2012. Stoneware. H. 14". (Photo, Carver Mostardi.)

David Mack and Luther T. Buie, Associate Dean, Pasco-Hernando State College, Sargent William Carney with Frederick Douglass and Harriet Tubman, tile panel, David Mack, Tampa, Florida, 2019. Stoneware. 24 x 48"

Frederick Douglass, face pot, David Mack, Spring Hill, Florida, 2008. Stoneware. H. 15". (Photo, Carver Mostardi.)

Dave “The Slave Potter” Drake, face pot, third edition, David Mack, Spring Hill, Florida, 2014. Stoneware. H. 15". (Photo, Carver Mostardi.)

Detail of the pot illustrated in fig. 13 (Photo, Carver Mostardi.) Inscribed on the pot: “I wonder where is all my relations / friendship to all – and every nation”

Jar, attributed to Thomas Chandler, Baltimore, Maryland, 1827. Saltglazed stoneware. H. 12 1/2". (William C. and Susan S. Mariner Private Foundation; photo, Robert Hunter.)

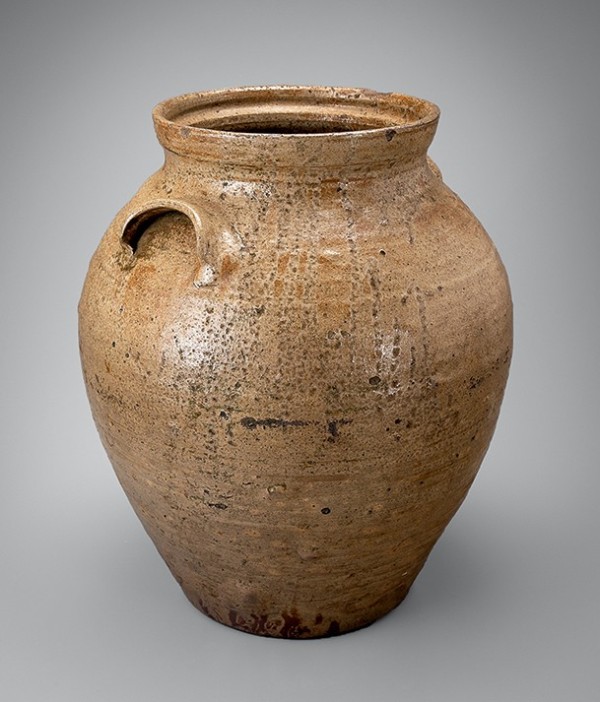

Jar, attributed to Marion Durham/Edgefield District, South Carolina, ca. 1840. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 16 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Making Vice President Kamala Harris and Associate Justice of the Supreme Court Ketanji Brown Jackson, face pot, David Mack, Spring Hill, Florida, 2022. Stoneware. H. 12". (Photo, Linda Mack.)

BORN AND RAISED in Baltimore, Maryland, I was a functional potter early in my ceramics career (fig. 1). From 1962 to 1964, I attended the Norfolk Division of Virginia State College, Norfolk, Virginia, currently known as Norfolk State University, and was taught by master potter Howard Johnson. Professor Johnson was the first professional potter I saw demonstrate live. He elevated my rough approach of throwing on the wheel and allowed my hands to be ONE with the clay. My second most influential art teacher was professor and sculptor James Lewis of Morgan State College, which I attended 1964–66 and then from 1969 to 1971 (in 1966 I was drafted into the US Army, where I served one year as an enlisted soldier, then attended Officers Candidate School, graduating as a 2nd Lieutenant; twenty-eight years later I retired at the rank of Lieutenant Colonel). Although I never took a ceramic class at Morgan State, Professor Lewis’s drawing class helped me to understand how the 2D linear visual process complements the 3D clay process and to pay attention to details. Johnson, in his late 80s, is still exhibiting and working in clay. Both of these great African-American artists and HBCU teachers were important mentors to my professional clay career.

From 1971 to 1975, I studied at the Maryland Institute College of Art under the tutelage of Professor Doug Baldwin (1939–2018). There I witnessed demonstrations by such legendary clay luminaries as Peter Voulkos (1924–2002), Daniel Rhodes (1911–1989), Toshiko Takaezu (1922–2011), and Rudy Autio (1926–2007).

Growing up, my life was intertwined with Marylanders who were connected to slavery and abolition, including Roger Brooke Taney (1777–1864), Chief Justice of the Supreme Court who wrote the majority opinion in the Dred Scott case; Thurgood Marshall (1908–1993), civil rights activist and the first African-American justice on the Supreme Court; and the abolitionist Frederick Douglass (1817/1818–1895). Taney was from Calvert County, Maryland, the same county as my great-great-great grandmother Henrietta Johnson, who was born a slave. I attended Frederick Douglass High School in Baltimore, Maryland, where Douglass had given the commencement address in 1894, one year before his death. Thurgood Marshall was also a graduate of Douglass High School.

After graduating, I taught art/ceramics K–12 in two school districts— Baltimore City and Clark County, Nevada—and I was an adjunct associate professor of ceramics at two colleges, Essex Community College in Maryland, and the Clearwater Campus of St. Petersburg College in Florida. In other words, I was a proficient potter, but while I felt comfortable in my skin and at the wheel, deep inside I felt something was missing. Because I was an art teacher, I did not have to rely on pottery to pay the bills. However, occasionally I would test my skills in the marketplace by participating in weekend outdoor art shows. My functional work was equal to that of my peers, but I soon recognized there was another element of concern—race. Most of my peers didn’t look like me, and that affected my sales.

The Emancipation of Clay

In 2004 I began to investigate that intangible, hidden element. I started to throw large vessels with sculptured faces of distinguished “people of color.” Suddenly, not only was I a minority potter but a minority innovator. Moreover, I felt proud, inspired, empowered, and connected to a lost Black cultural generation of heroes and sheroes (fig. 2).

Before discussing my connection to the history and spirit of the Abolitionist movement, let me first dig deeper into world history and investigate the reason for abolitionism—slavery. Many people believe slavery began with the transatlantic slave trade that brought men, women, and children from the West Coast of Africa to the Americas. However, the Indian Ocean slave trade, also known as the East African slave trade or the Arab slave trade, occurred as early as 3500 bce with ancient Babylonians, Egyptians, Greeks, and Persians.

The Indian slave trade persecuted people based on their religion, whereas the transatlantic slave trade persecuted people by the color of their skin, their race. The Indian slave trade consisted of concubines, sex slaves, and soldiers who could be manumitted. In contrast, the transatlantic slaves were abducted and sent to the Americas as a labor force, with no options for freedom. This deplorable condition, to control a human’s life, mind, and soul as expendable property, gave rise to some of the most daring revolts in history, such as the siege of Port-au-Prince during the Haitian Revolution (1793), the Armistead Revolt (1839), the commandeering of a Confederate ship by Robert Smalls (1862), and Harriet Tubman’s raid on Combahee Ferry (1863).

My Practice

I believe the most important part of working with clay is the first stage of wedging and kneading. Without connecting with the clay as “one,” the process is incomplete. Even my limited knowledge of Native American and Japanese pottery helps me to focus on the spiritual aspect of this magical raw material, and to remember to respect the process at all times. I started throwing thirty–forty pounds of clay on the wheel to make a single, rectangular human form. These ultimately became the beginnings of my series Heritage Face Vessels.

After completing pots depicting the inventor Elijah McCoy (fig. 3), entrepreneur, philanthropist, and activist Madam C. J. Walker, (fig. 4), and some other large pots, I realized the pieces were too heavy to transport for display at outdoor exhibition spaces. To make them more convenient and affordable, I decided to throw ten pounds instead. Most of my work is stoneware clay that was electric-fired at cone 5, glazed or treated with underglaze decoration before bisque firing, and then glazed and fired again.

The George Washington Carver (1864–1943) vessel celebrating the agricultural scientist is my most ambitious project (fig. 5). I used natural peanut shells dipped in porcelain slip, bisque, and glazed fired. The real shells burned off, resulting in perfect porcelain ones.

Despite some visual similarities, I was not influenced by nineteenthcentury American face vessels. I woke up one day with the vision to make this a more inclusive, diverse world by creating clay vessels depicting distinguished and forgotten people of color. The first face pot I created was The Three Faces of Martin Luther King Jr. (fig. 6). Martin Luther King Jr. (1929–1968) had a profound impact on the Black community, the civil rights movement, and specifically my generation of baby boomers.

I selected my earliest pre-revolutionary vessel to be of Crispus Attucks (fig. 7). Not much is known about Attucks (1723–1770) except that he was the first American shot during the Boston Tea Party in 1773, a martyr of the American Revolution. Crispus Attucks won top ceramic honors at the 2020 Star Spangle Art Show, sponsored by the Military Officers Association of America, Tampa Chapter, The James A. Haley Veterans’ Hospital, and Leepa-Rattner Museum of Art at the Tarpon Springs Campus of St. Petersburg College.

Harriet Tubman (ca. 1822–1913), the abolitionist who escaped slavery and then led thirteen missions via the Underground Railroad to rescue others, and Sojourner Truth (ca. 1797–1883), the abolitionist and woman’s rights activist, were etched into my brain at an early age and became subjects of two of my pots (figs. 8, 9).[1]

In addition to celebrating activists, I also focused on African-American cultural, scientific, business, and military leaders. Phillis Wheatley (ca. 1753– 1784), born a slave and educated in Boston, was the first African-American woman to publish a book of poems, many of which spoke out against slavery (fig. 10). Tragically, she died at age thirty-one. When folks talk about “The Real McCoy,” it is not Hatfield vs. McCoy but Elijah, the Real McCoy (1844–1929) (see fig. 3), who invented an automatic lubrication machine that would allow steam engines to continue operations without shutting down. Although Madame C. J. Walker (1867–1919) did not invent the straightening comb, her hair products and cosmetics were distributed globally (see fig. 4). She became a self-made millionaire, and her products are still popular today.

So dear to my military heart are the heroics of Sargent William Carney (1840–1908), from the famed 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment, who would not allow the American flag to touch the ground during the Civil War battle of Fort Sumter, South Carolina (fig. 11). Wounded several times, Carney became the first African-American to receive the Medal of Honor, the nation’s highest military award.

The great Frederick Douglass (1818–1895) was always a man I admired and felt connected to (fig. 12). Many folks are unaware that Douglass met with Abraham Lincoln to promote Black soldiers’ participation in the Civil War. Douglass helped to mobilize the 54th Massachusetts All Black Infantry Division, of which his sons were members. Douglass thought that he would become the first Black Brigadier General, although that did not happen. I wrote a military dissertation on Douglass, and I continue to search my roots to confirm the stories told to me by my beloved mother, Ethel Mack, that I am a descendant.

In addition to portraying people of color on my pots, I also began to advocate for recognition of the potters of color who have gone before us. In 2020 I published “Enslaved and Freed African American Potters” in Ceramic Monthly, which presented an argument for the return of artifacts made by enslaved artists to their rightful descendants.[2] A year later, a congressional act was born, the Stolen Bones Act of 1619 (SBA), and as I write this in the spring of 2022, efforts to amend SBA with HR 3005, a bill directing the replacement of a bust of Roger Brooke Taney in the old Supreme Court Chamber of the U.S. Capitol with one of Thurgood Marshall, is a real possibility.

David Drake

The last vessel from my collection illustrated here is of the talented, rebellious David Drake (ca. 1801–after 1870), slave, poet, and potter who lost three wives, and eight children (figs. 13, 14).[3] Drake defied South Carolina law by writing and signing his pots.[4] His work is now rightly celebrated, featured prominently in museums and selling for vast amounts; one of his pots sold in 2021 for $1.56 million, the highest price yet paid for a piece of American pottery, although his descendants received no compensation.[5]

As we move forward, it is important to recognize the differences between “enslaved” and “freed” Black potters. We should never forget that one operated within a lifetime of bondage and the other as a free man. Museums sometimes forget to consider those complexities, emphasizing only the aesthetic qualities of the artwork. To combine an exhibition of the works of enslaved potter David Drake with freed potter Thomas Commeraw is surely disrespectful, discourteous, and insulting.

When writing or talking about enslaved potters, you must show the good, the bad, and the ugly. Be holistic and tell the whole story . . . the toxic nature of mixing and firing clays, the danger of lead-glaze formulation, the unsanitary factory conditions, dawn-to-dusk work hours, family separations, physical and sexual abuse, and theft of birth. Museums must get this right, or we will continue to perpetuate the old myth that all slaves were happy and beloved property, that one could lose a limb only by a speeding train: the David Drake saga.

Some have said that David Drake’s leg was cut off by a train when he got drunk one night and fell across a train track. I and other historians believe that story is nonsense! I believe his leg was amputated by his master for writing on his pots, and possibly teaching other slaves to read and write. Between 1843 and 1848, immediately after the leg incident, Dave went through a silent period where he did not write on a pot for five years. Coincidence? I don’t think so.

A Baltimore Connection to Edgefield

Thomas Chandler (1810–1854), born in Virginia and trained in the potteries of Baltimore, became one of the more prolific potters working in the Edgefield District of South Carolina and was linked to David Drake and the white potters who owned him.[6] As a native Baltimorean, I was intrigued by Thomas Chandler’s connection to Baltimore, Edgefield, and Guadalupe, Texas. In the nineteenth century Baltimore was the epicenter of pottery manufacturing due to its rich deposits of raw clay, the transatlantic slave trade, and shipping infrastructure. It is of little wonder that Chandler landed in Baltimore to complete his ceramic apprenticeship (fig. 15). However, I weep with sorrow when reading Chandler’s Deed of Trust that listed his estate: wagon, mules, horse, furniture, and—on the same page with no distinction—four slaves: Simon, Ned, Easter, and John. To list one’s personal property along with a “Godly Created Human Being” is beyond comprehension, but that was the culture of slavery. However, when you enlist in the military to defend and serve your country, as Chandler did, then go AWOL on three occasions, being a slave owner would not necessarily be out of character. America, do you understand why Black Americans hate and despise the Confederate flag and all icons/statues that represent the cause of the Civil War and slavery?!

As we continue to connect the dots, Chandler’s slave John eventually attained freedom and migrated to Guadalupe, Texas, with a white potter, Marion Durham, to work for a slave-labored pottery factory owned by the Rev. John M. Wilson. Some believe they brought with them the Edgefield alkaline-glaze formula (fig. 16). The Durham and Chandler pottery partnership was a rare interracial relationship during the Antebellum era. The Rev. Wilson’s slave-labored pottery factory would also develop and produce the Wilson Brothers Pottery, the first Black entrepreneurs to operate and own a business in the state of Texas. After Emancipation, the founder Hiram, with brothers James and Wallace, opened a factory in Capote, Texas, and manufactured clay pots from 1869 until Hiram died in 1884. Distribution of their pottery reached as far as California. Their business was so successful they built a school, church, and a cemetery for their community. Along with the three brothers, the pottery staff included potters Andrew Wilson and George Wilson, who had also worked at the Guadalupe pottery.

The Ongoing Journey

I continue to work toward the broader recognition of the accomplishments of Black ceramic artists to keep hope alive. Museums, universities, and other organizations that exhibit, publish, or study ceramics must educate the next generation about the contributions of the Black artists of the past, such as Augusta Savage (1892–1962), Thomas Commeraw, Edmonia Lewis (1844–1907), Richmond Barthe (1901–1989), and Selma Burke (1900–1995), as well as those of the present, among them Larry Allen, Jim McDowell, David MacDonald, Winnie Owens, Howard Johnson, Dudley Vaccianna, and James Watkins, to mention just a few. Kudos to the up-and-coming clay activists Roberto Lugo, Kelly and Kyle Phelps, Niki Savva, PJ Anderson, and Osa Atoe for taking up the baton and standing on the shoulders of our great Black clay ancestors. I also continue to make pots for my Heritage Face Vessels series, the most recent celebrating Vice President Kamala Harris and Associate Justice of the Supreme Court Ketanji Brown Jackson (fig. 17).

Institutions, organizations, and publications need to educate their readers about Black ceramic artists and provide minority residency, workshops, and programming that are diverse and inclusive. Black students must see a ceramic artist that looks like them, and believe it is attainable to have a successful career in clay as a minority artist. Congratulations to Penland, Arrowmont, Ceramic Monthly, the National Council on Education for the Ceramic Arts (NCECA), Ceramics in America, and others for adopting inclusive minority transparency.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS For the readers who were unaware of the accomplishments of my Heritage Face Vessels, thank you for allowing me to educate you. For those who were already privileged to this information, please share it with your friends. My thanks to Rob Hunter, Ron Fuchs, and the Chipstone Foundation for the opportunity to showcase my abolitionist monuments and share a part of my fifty-year ceramic experience with readers of Ceramics in America.

I attended Morgan State College, one of the nation’s historically Black colleges and universities, in Baltimore, Maryland, where two female dormitories were named Truth Hall and Tubman Hall.

David F. Mack, “Enslaved and Freed African-American Potters,” Ceramics Monthly (September 2020), available online at https://ceramicartsnetwork.org/ceramics-monthly/ceramicsmonthly-article/Enslaved-and-Freed-African-American-Potters# (accessed June 8, 2022).

April Hynes, “Where Is All My Relation . . .” blog post, The Wanderer Project, July 12, 2016, available online at https://thewandererproject.wordpress.com/2016/07/12/where-is-allmy-relation/ (accessed August 18, 2022).

There are numerous publications on the life and work of David Drake, including Jill Beute Koverman, I made this jar: The Life and Works of the Enslaved African-American Potter, Dave (Columbia, S.C.: McKissick Museum, 1998); Arthur Goldberg and James Witkowski, “Beneath His Magic Touch: The Dated Vessels of the African-American Slave Potter Dave,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2006), pp. 58–92; Leonard Todd, Carolina Clay: The Life and Legend of the Slave Potter Dave (New York: W.W. Norton, 2008); Lisa Farrington, African-American Art: A Visual and Cultural History (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017); Michael Chaney, ed., Where Is All My Relation? The Poetics of Dave the Potter (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018).

“Crocker Farm Smashes American Pottery Record with $1.56 Million Dave Jar,” Antiques and the Arts Weekly, August 7, 2021, available online at https://www.antiquesandthearts.com/crockerfarm-smashes-american-pottery-record-with-1-56-million-dave-jar/ (accessed June 12, 2022).

Philip Wingard, “From Baltimore to the South Carolina Backcountry: Thomas Chandler’s Influence on 19th-Century Stoneware,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2013), pp. 38–76.