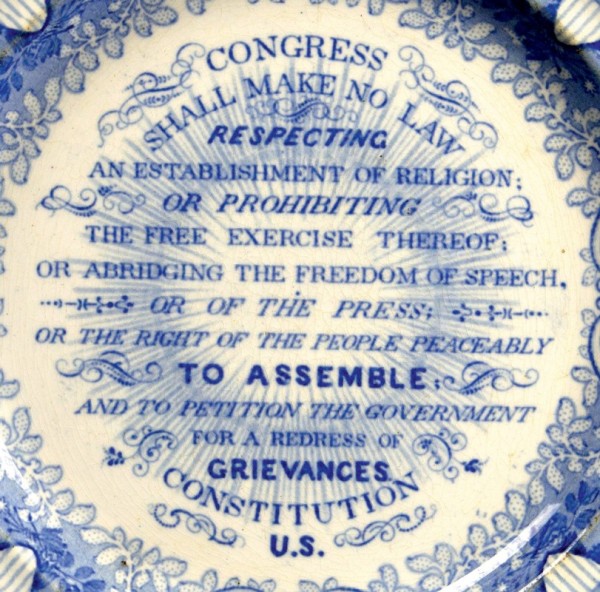

Plate, Staffordshire, England, ca. 1838. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 7 3/4". (Private collection; photo, Neil Ewins.)

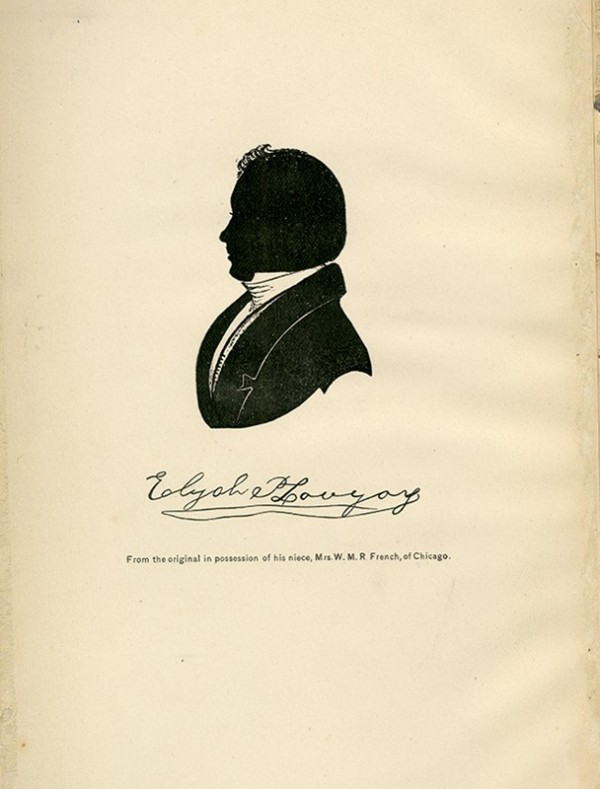

“Elijah P. Lovejoy,” from Henry Tanner, The Martyrdom of Lovejoy (1881), unpaginated. (Special Collections and College Archives, Musselman Library, Gettysburg College.)

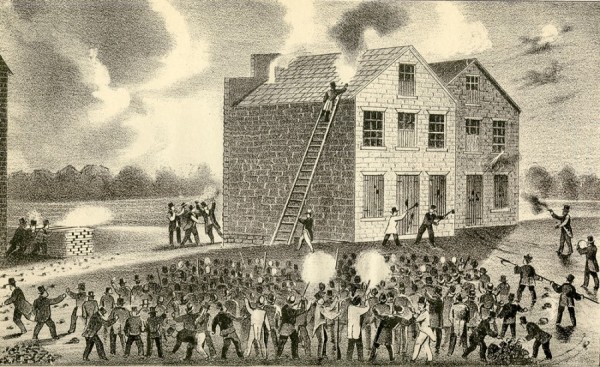

“The mob attacking the warehouse of Godfrey Gilman & Co., Alton, Ill., on the night of the 7th of November, 1837, at the time Lovejoy was murdered and his press destroyed,” from Henry Tanner, The Martyrdom of Lovejoy (1881), unpaginated. (Special Collections and College Archives, Musselman Library, Gettysburg College.)

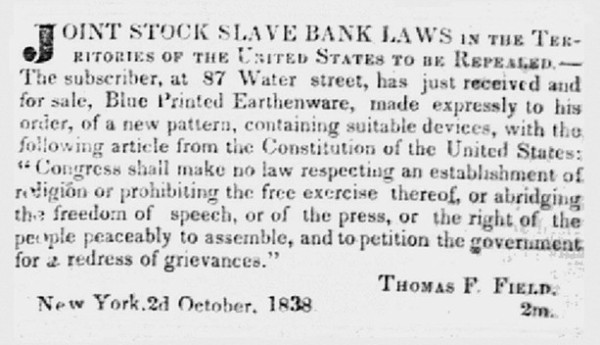

Advertisement, The Emancipator (New York), November 8, 1838, p. 101. (Courtesy, NewsBank / Readex.)

Detail of the plate illustrated in fig. 1 showing the First Amendment of the United States Constitution.

Advertisement, The Emancipator (New York), October 11, 1838, p. 97. (Courtesy, NewsBank / Readex.)

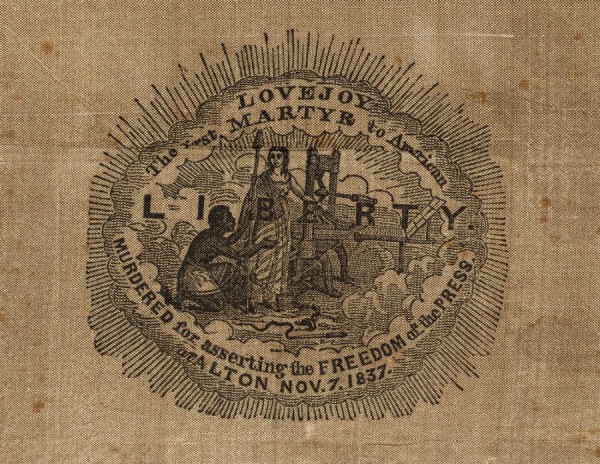

Detail of the plate illustrated in fig. 1 depicting a printing press and an enslaved person. Inscribed: LOVEJOY / The first MARTYR to American / LIBERTY / ALTON NOV. 7. 1837. (Private collection; photo, Neil Ewins.)

Printed ribbon, United States, 1837–1840. Silk. L. 4 1/4". (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

Cup plate, Staffordshire, England, ca. 1838. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 4". (Private collection; photo, Neil Ewins.)

Jugs, Staffordshire, England, ca. 1838. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. of tallest 6 1/4". (Collection of Rex Stark; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Plate, Staffordshire, England, late nineteenth century. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 9 1/4". (Reeves Museum of Ceramics, Washington and Lee University; photo, Robert Hunter.)

ONE OF THE ATTRACTIONS OF ceramic history is the possibility of finding new information that questions previous views and assumptions. A case in point is the production of ceramics commemorating the death of the Reverend Elijah Lovejoy (1802–1837), the proprietor of an abolitionist newspaper in Alton, Illinois, who was murdered by a pro-slavery mob on November 7, 1837 (figs. 1-3). This article examines how the design originally was interpreted as derived from a careful examination of advertising and other press accounts.

The Tragic Act

The murder of Elijah Lovejoy was widely reported in the contemporary press and galvanized anti-slavery activists. One of Lovejoy’s friends, the Reverend Edward Beecher (1803–1895), even wrote Narrative of Riots at Alton, first published in 1838. The reverend’s sister, Harriet Beecher Stowe (1811–1896), later published Uncle Tom’s Cabin, indicating how firmly various members of the Beecher family were committed to the abolitionist cause.

At a glance, the facts seem straightforward. Lovejoy moved to Alton where he attempted to run his abolitionist newspaper. He was met with local resistance by pro-slavery activists. There was a riot, and in the ensuing chaos Lovejoy was shot and killed. As a form of protest, transfer-printed designs were manufactured, which came to be known as “Constitutional” or “Anti-slavery” wares.

The Myth

Interest in so-called historical Staffordshire wares (that is, ceramics manufactured for the American market and decorated with American scenes) by ceramic historians and collectors developed rapidly in the second half of the nineteenth century. Early-American ceramic historians developed various theories as to why certain designs were produced, and the Lovejoy design received a fair amount of attention. For instance, Alice Morse Earle stated in China Collecting in America (1892): “It is asserted that the pieces bearing this design were the gift of the English Anti-Slavery Society to the American Abolitionists, shortly after the death of Lovejoy; that they were sold at auction in New York, and the proceeds devoted to the objects of the Society of Abolitionists. If this account is true, these plates are certainly among the most interesting relics of those interesting days.”[1]

In 1903, N. Hudson Moore (another Early American ceramics historian) suggested that this ceramic design was a gift from English anti-slavery supporters to the American abolitionists, and even indicated that these plates had been targeted for forgery.[2] Ellouise Baker Larsen (the author who produced the most comprehensive survey of printed wares destined for the American market) believed that the design was certainly manufactured in Staffordshire, and was used to raise money for freeing enslaved people in the United States.[3]

Gradually the interpretations shifted from speculative to opinions more engrained into the fabric of ceramic history.[4] Sam Margolin’s 2002 article “‘And Freedom to the Slave’: Antislavery Ceramics, 1787–1865” repeated the idea that the wares were donated by British abolitionists to raise money for the anti-slavery cause, and that the design was faked in the late nineteenth century. He suggests that in a wave of indignation the “Staffordshire potters memorialized” Lovejoy in their wares.[5] This view fits more easily into a typical notion of ceramic history, whereby the manufacturer produces merchandise skillfully adapted to appeal to consumer demand. Any contribution that intermediaries may have had in this process has often been neglected.

The Reality

On closer analysis, the relation between the manufacturer and importers and dealers was more complex. In 1838 Thomas F. Field, a crockery dealer in New York, claimed that a printed design (matching a description of the Lovejoy wares) was “made expressly to his order, of a new pattern” (fig. 4). It is interesting how advertisements for these Lovejoy wares and for Edward Beecher’s Narrative of Riots at Alton appeared in the same column of The Emancipator in October 1838. The advertisement quotes the phrase “Congress shall make no law...,” which is also what appears on the printed wares commemorating the death of the Rev. Elijah Lovejoy (fig. 5). The Emancipator included a more detailed description of so-called Constitutional Ware, and poignantly mentions how the design incorporated an enslaved man kneeling at the figure of Liberty pointing to a printing press (figs. 6, 7). Silk ribbons were printed with the same image, and it was either them or a broadside or book that Field used as the design source (fig. 8).[6] In addition to plates, cup plates and jugs are known (figs. 9, 10).

From about 1822, Thomas F. Field was located in Utica, a city in upstate New York that was a center of abolitionist activity, and was described as being in a partnership with one Theodore Clark from 1824 until 1829.[7] By 1833 Field was in New York City running a china store.[8] Transfer-printed ceramics exist with the impressed mark of “Field & Clark, Importers of Earthenware, Utica”, that were manufactured by Enoch Wood of Burslem. Given that these marked pieces show a direct connection between Enoch Wood and Field & Clark, it is possible that the Elijah Lovejoy commemorative design was manufactured by Enoch Wood & Sons. However, no marked pieces have been identified that would prove this attribution.

On April 7, 1823, Thomas F. Field, a “merchant of Utica,” married “Miss Mary Ann, eldest daughter of David Roberts of this city,” at a ceremony officiated by the Rev. John Williams of the Baptist Church on Oliver Street in New York City.[9] At a meeting held on February 18, 1828, at the Methodist Chapel in Utica, Thomas Field was appointed as one of the commissioners resolved to prevent violation of the Sabbath.[10] Field became president of the Baptist Central Tract Society of Utica, founded in April 1828, and secretary of the Oneida Bible Society of New York.[11] The Baptist Central Tract Society claimed to have distributed 150,000 tracts in 1830, and Field was still active as the president in 1831.[12] Clearly Field had strong religious convictions, and it is apparent that his Baptist values affected his behavior. In 1841 he was described as president of the Baptist Anti-Slavery Society of New York, emphasizing how his sociopolitical and religious views mirrored what he promoted.[13]

In an article in The Friend of Man, Utica’s abolitionist newspaper, it was reported that specimens of Field’s plates had been discovered in October 1838 at the Anti-Slavery Office in New York City. The author of the newspaper article explained how he had proceeded to Field’s New York store at 87 Water Street to purchase a dozen plates for his personal use. The writer also believed that “[t]he pattern was made to his [Thomas Field’s] own order, and, so far as we know, he is the only man in his business who has dared to put his finger upon the ‘peculiar institution.’”[14] A comment that appeared under the heading “Scraps” in a Hartford, Connecticut, newspaper mentions how Messrs. Field & Co. was advertising “anti-slavery earthenware,” but then asked, “What sort of an animal is that?”[15]

Based on these comments, it is uncertain there was sufficient demand for the design to generate enough profits to benefit enslaved individuals, as several authors have suggested. Thus, it is important to recognize how the design was, at that time, considered to be touching on an issue of acute sociopolitical tension rather than an example of Field (or the Staffordshire manufacturer) identifying some marketing opportunity. As indicated above, Field’s own position on abolitionism was made clear when he became president of the Baptist Anti-Slavery Society in 1841. The contemporaneous interpretation, pieced together from newspaper notices and advertisements, is rather different from the opinions expressed by nineteenth-century collectors and writers.

There is nothing in Field’s advertisements to indicate that any profits were used to support anti-slavery activities, nor is there evidence to support the theory that it was a gift (as Alice Morse Earle suggested) from the English Anti-Slavery Society to be sold at auction. Although the anti-slavery plate might not have been in high demand, the importance to contemporaries was, according to The Friend of Man, that dining tables were furnished with this crockery, and the plates could at least “silently preach abolitionism” to guests and children “on sound principles.”[16] Clearly, it was envisaged that the Lovejoy design was for use and not merely for display, and Field continued to advertise his “Anti-Slavery Earthenware” plates and pitchers in the New York Spectator from March until June 1839.[17]

The Unpalatable Truth

A positive result of this article would have been for it to convey a new interpretation of the Lovejoy design, infinitely more desirable than the historical myth. Alas, this was not to be the case. Jeffrey B. Snyder wrote in Historical Staffordshire: American Patriots and Views (1995) that the Lovejoy plate “was popular with the Abolitionist’s movement in the Northern states of the United States,”[18] but on closer analysis it is doubtful that Thomas F. Field was responding to American demand. Field had his views, and it was observed in a Boston newspaper of 1834 that he had courageously marketed his New York business as an “Abolition China Store” long before the death of the Rev. Elijah Lovejoy in 1837. A notice in the Liberator in August 1834 as to what the mob might do to Field’s crockery store is a poignant reminder of how the views of merchants were not necessarily in unison with attitudes of the consumers. The actual notice read: “Thomas F. Field, of New-York, ‘offers for sale an amalgamation of colors and qualities of French, English, and India China Tea and Dining Seats [sic],’ and styles his store an ‘Abolition China Store.’ If the mob scent out this amalgamation, there may be shocking work among the crockery.”[19]

The example of the Lovejoy design rather reinforces how importers could have multidimensional personalities, as well as being involved in their mercantile trade. In fact, Thomas F. Field’s obituary indicates that apart from being described as the “oldest crockery merchant or dealer in this State,” he “was at one time prominent in municipal politics, first as a Whig, then as an Abolitionist, and finally, as a Republican.”[20] When Field stood as an Abolition candidate for mayor of New York in 1842, he received only 136 votes, whereas the Democrat candidate received more than 20,000 and the Whig more than 18,000.[21]

Conclusion

Although the early publications concerning historical Staffordshire ceramics appeared to have jumped to an incorrect conclusion as to why the Lovejoy design was produced, the pioneering research by connoisseurs still has significance. These publications already began to recognize how some designs were rarer than others, impacting on their collectible status. N. Hudson Moore’s The Old China Book (1903) pointed out: “A year or two ago I wrote that ‘historic cup-plates were worth their weight in gold,’ and some of my correspondents took exception to my statement [see fig. 9]. Within a few weeks I have heard of two four-inch Lovejoy cupplates which have come upon the market. . . . The first was sold at public auction in New York City, and brought twenty-three dollars.”[22]

While it is now appreciated that ceramic patterns could be commissioned by a single importer, the implications of this are that the number manufactured, sold, and distributed was probably limited. Hence, we begin to have an explanation as to why some ceramic designs associated with the American market were seemingly rare. In 1903 Moore pointed out that “[i]t is unfortunate that this fine old piece was selected for forgery. Any person who is used to handling this old ware gets to detect the differences by mere touch that would escape the casual observer. Not only were the forged plates heavier, but they were thicker, and colder to the hand.”[23]

Two versions of the plates are known and seem to support Moore’s fear that there were later versions; there are surviving plates printed in a lighter tone, of a slightly larger size, which are thicker and more in ivory color than the originals (figs. 1, 11).[24] That suggests that these larger plates are later, either as honest copies made to celebrate another occasion, or as dishonest forgeries meant to fulfill a demand for the rare originals.

While there has been growing recognition of how ceramic importers and dealers could influence production, this is normally on the basis that intermediaries—being closer to the consumer—had a better understanding of demand. For example, Regina Blaszczyk’s Imagining Consumers: Design and Innovation from Wedgwood to Corning (2000) argues that merchants were in touch with the consumer and, therefore, “harvested meaningful data about tastes and purchasing habits.”[25] In actuality, the comments of contemporaries infer that the Lovejoy subject was a controversial one, and when it is appreciated that this ceramic design was actually orchestrated by an importer who was originally from England, it is perhaps more akin to an outsider making a comment about slavery in the United States.[26] In certain instances, what was marketed by importers and dealers could reflect their own, individual concerns.

For ceramic historians today, it remains important to reexamine previous interpretations of what certain ceramic objects might signify. Even from a twenty-first-century perspective, David Fischer has interpreted the Lovejoy ceramic design (now shown to be commissioned by Thomas F. Field) as one example of the “outpouring” of imagery concerned with abolition and civil liberties after the Reverend Lovejoy’s murder in 1837—assuming that the production of the physical object was a logical reflection of prevailing attitudes.[27] As this article has demonstrated, the importance of examining the origins, backgrounds, and identities of crockery importers and dealers grows in significance, since what was advertised did not simply emanate from the Staffordshire manufacturer or was a response to the perceived demands of the consumer.

Alice M. Earle, China Collecting in America (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1892), p. 333

N. Hudson Moore, The Old China Book, including Staffordshire, Wedgwood, Lustre, and Other English Pottery and Porcelain (New York: Frederick A. Stokes Co., 1903), p. 79.

Ellouise Larsen, American Historical Views on Staffordshire China, rev. ed. (1939; New York: Doubleday, 1950), p. 242.

Marian Klamkin, American Patriotic and Political China (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1973), pp. 102–4; Bridget T. Heneghan, Whitewashing America: Material Culture and Race in the Antebellum Imagination (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2003), p. 14.

Sam Margolin, “ ‘And Freedom to the Slave’: Antislavery Ceramics, 1787–1865,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2002), pp. 95–97.

Ribbons like these were designed to be worn around the arm as a sign of mourning.

Robert H. McCauley, “American Importers of Staffordshire,” Antiques (June 1944): 295– 97, indicates that Field opened a crockery store at Utica in 1822; advertisement, “Utica, May 25, First arrival from Liverpool—Messrs Field and Clark . . . 50 packages [of ] elegant crockery ware,” Watch-Tower (Cooperstown, N.Y.), May 31, 1824, p. 3; “Dissolution” notice, Christian Journal (Utica, N.Y.), October 16, 1829, p. 4.

Longworth’s American Almanac, New-York Register and City Directory (New York: Thomas Longworth, 1833), p. 258.

“Married,” National Advocate (New York, N.Y.), April 9, 1823, p. 2.

“Meeting at Utica,” Connecticut Observer (Hartford), March 3, 1828, p. 1.

Notice, New-York Baptist Register (Utica), November 28, 1828, p. 3; “Oneida Bible Society, N.Y.,” Philadelphian, May 23, 1829, p. 1

“Religious Compendium,” Christian Watchman (Boston), February 12, 1830, p. 3; “Utica Central Baptist Tract Society,” New-England Baptist Register (Boston), February 9, 1831, p. 3.

“Baptist A. S. Soc. of N.Y. City and Vicinity,” Christian Reflector (Worcester, Mass.), June 16, 1841, p. 3.

“Anti-Slavery Earthen Ware,” Friend of Man (Utica, N.Y.), October 17, 1838, p. 279.

“Scraps,” Times (Hartford, Conn.), September 21, 1839, p. 1.

“Anti-Slavery Earthen Ware,” Friend of Man (Utica, N.Y.), October 17, 1838, p. 279.

The advertisement reads: “ANTI-SLAVERY EARTHENWARE Plates and pitchers, and a general assortment of China, glass and earthenware of the latest and best patterns for sale. Country merchants who regard the quality of ware will find it to their interest to call and examine my stock at 87 Water Street. Thomas F. Field.” Spectator (New York), March 18, 1839, p. 3.

Jeffrey B. Snyder, Historical Staffordshire: American Patriots and Views (Atglen, Pa.: Schiffer Publishing, 1995), p. 108.

“Notice,” Liberator (Boston), August 30, 1834, p. 139.

“Obituary,” New York Tribune, September 15, 1877, p. 5.

“The Vote for Mayor,” Albany Argus (Albany, N.Y.), April 22, 1842, p. 3.

Moore, The Old China Book, p. 46

Ibid. pp. 79–80.

I am extremely grateful to Ron Fuchs II and Robert Hunter for undertaking an analysis of the Lovejoy plates in the collection of the Reeves Museum of Ceramics, Washington and Lee University.

Regina Blaszczyk, Imagining Consumers: Design and Innovation from Wedgwood to Corning (Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2000), pp. 32–33.

Certificate of Death, Thomas F. Field, September 15, 1877, Brooklyn, New York. New York City Municipal Archives. The certificate indicates that Thomas Field arrived in the United States in circa 1815; 1870 Census, Brooklyn, New York.

David H. Fischer, Liberty and Freedom: A Visual History of America’s Founding Ideas (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), p. 280.